Prevalence, Patterns and Implications of Gender-Based Violence against Women: Challenges and the Way Forward

Sigamani Panneer, Jawaharlal Nehru University & Assam University

Saranya Sundarraju, Jawaharlal Nehru University

F.X. Lovelina Little Flower, Bharathiar University

Hilaria Soundari Manuel, Gandhigram Rural Institute

R. Revanth, Bharathiar University

Abstract & Keywords: The alarming incidence of Gender-Based Violence (GBV) highlights a critical humanitarian crisis that necessitates urgent consideration and collaborative endeavours to alleviate human suffering and advance principles of equity and security for every person. Women and teen girls are primarily affected by GBV. Patterns of GBV against women and teens are sexual, emotional, and physical. Nearly one in three women, or 736 million women and teen girls, have experienced intimate partner abuse, non-partner sexual violence, or both. A systematic review was conducted to understand the forms of GBV, and Women's knowledge of protective legislation. Studies were selected in a systematic manner to understand the interrelated forms of violence (such as physical, sexual, economic, and psychological abuse) that women and teen girls experience. The review prioritizes the best practices by highlighting the feasible approaches and priorities for addressing GBV effectively.

Keywords: Gender-based violence; intimate partner violence; non-partner violence; women and teen girls law; and support systems

Gender-Based Violence and its Patterns

The Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC) defines Gender-Based Violence (GBV) as any harmful act committed without consent, which is rooted in socially assigned gender disparities between males and females (WHO, 2002). Physical, sexual, or mental harm or suffering, as well as threats of such harm or suffering, coercion, and other types of deprivation of liberty, are all included. These activities can occur in both public and private settings. GBV aspects can be physical, psychological, sexual, and economic. This includes acts such as rape, sexual assault, physical assault, coerced marriage, deprivation of resources, opportunities, or services, as well as psychological or emotional mistreatment (UNHCR, 2020). These are some examples of different forms of violence and exploitation, such as intimate partner violence, crimes related to "honour," sexual abuse of children, forced marriages of children, female genital mutilation, and human trafficking for sexual exploitation, which includes sexual slavery, domestic servitude, and forms of marriage where one person is treated as a servant (GBVIMS, 2006; Andrew Morrison et al., 2007). Both men and women and teen Girls can be the victims of these types of violence, but Women and Teen Girls are mostly affected. According to data, almost one in every three Women and Teen Girls, or approximately 736 million Women and Teen Girls, have been subjected to intimate partner violence, non-partner sexual violence or both at least once in their lifetime (WHO, 2021).

One in ten females under the age of 20 have engaged in forced sexual activity globally, and one in three girls who have ever been married between the ages of 15 and 19 have undergone emotional, physical, or sexual abuse at the hands of their spouses or partners (UNICEF, 2014). According to data, up to seven out of ten females aged 15 to 19 who had experienced physical or sexual abuse never sought assistance; many of them claimed they did not believe it to be abuse or did not view it as a problem (UNICEF, 2014). Sexual violence may be used to perpetuate unequal gender norms of masculinity and femininity. Women and Teen Girls may also be singled out because of their vulnerable status and influence as a result of diversity or other intersecting injustices. Men and boys are more likely to be sexually abused as a result of factors like socio-economic status, birth country, and legal status, including asylum status (UNHCR, 2016). Violence against men stems from socially constructed notions of masculinity and power. Men (and occasionally women) use it to injure other men. Similar to violence against women and girls, male survivors may not report this violence due to stigma connected with masculinity norms, such as discouragement from acknowledging vulnerability or suggesting they are flawed (UNFPA, 2019).

In comparison to males, evidence from numerous literature reviews throughout the world shows that Women and Teen Girls are the most vulnerable population to GBV. In India, mainly Women and Teen Girls are being affected more than men due to the patriarchal system and the cultural norms supporting it (Dery, 2014). According to the report by the National Crime Records Bureau, there was a recorded total of 428,278 crimes committed against women in 2021, indicating a notable rise of 15.3% compared to the previous year's figure of 371,503 occurrences. The majority of cases about crimes against women under the Indian Penal Code were reported under the category of "Cruelty by Husband or His Relatives," accounting for 31.8% of the total cases. This was followed by "Assault on Women with Intent to Outrage her Modesty" at 20.8%, "Kidnapping & Abduction of Women" at 17.6%, and "Rape" at 7.4%. In 2021, the recorded crime rate per one hundred thousand women population was 64.5%; in 2020, it stood at 56.5% (NCRB, 2021). Globally, around 650 million Women and girls were married before 18 years (UNICEF, 2019). In 2020, over 47,000 women and teenage girls were victims of fatal violence inflicted by their intimate partners or other family members. This statistic indicates that, on average, a woman or girl is murdered by a family member every 11 minutes (UNODC, 2021). Women and girls account for 71% of all victims of human trafficking, with 3 out of 4 being sexually exploited (Akhmedshina, 2020). Family and friends, community members, and strangers can all commit GBV against Women and Teen Girls. Thus, it is essential to study the prevalence, patterns and implications of GBV against Women and Teen Girls and multiple support systems for the prevention and mitigation of the victims.

Review Methods

The objective of this systematic review was to explore the current state of knowledge regarding the prevalence, patterns, aspects, and implications of gender-based violence against women and girls and the support systems available for them in India. By addressing the research question, the systematic review can provide a holistic understanding of the status of GBV in India and its implications.. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines were adopted to ensure the quality and transparency of reporting.

Search Strategy

The comprehensive search for relevant literature commenced on April 20, 2021, employing a meticulously designed search strategy across two prominent databases: Web of Science and Scopus (accessible through Elsevier) for interdisciplinary field coverage. Additionally, a manual search of the reference lists of the included studies was conducted using the Google Scholar search engine. The search strategy revolved around three key concepts: gender-based violence (1) at home, (2) in the community, and (3) in the workplace. For statistical data and definitions, government reports and recognized international organization websites were consulted. The keywords employed for the literature search included Violence against Women and Teen Girls, Gender-based violence, Workplace violence, Domestic violence, Community violence on Women and Teen Girls, Sexual harassment, Economic violence on Women and Teen Girls, Mental abuse on Women and Teen Girls, Pandemic violence against Women and Teen Girls, COVID-19 and GBV. The search syntax in the platforms included the Boolean operators “AND” and “OR” for a combination of the keywords.

Inclusion and Exclusion criteria

We developed prespecified eligibility criteria to determine the inclusion of abstracts and articles. The retrieved abstracts and articles that did not meet our research objective were excluded.

Table 1: Inclusion and Exclusion criteria for selecting the articles for the study.

|

Inclusion |

Exclusion |

|

Peer-reviewed original studies |

Studies without primary data |

|

Publication year from 2010 to 2021 |

Studies which involve senior citizens |

|

The population included Women and Teen Girls aged 18 – 60 years. |

Preprint articles |

|

|

|

|

English language |

Research Protocols |

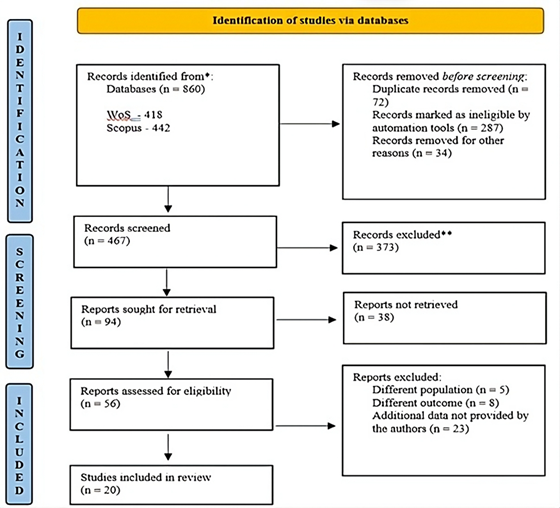

A total of 860 articles were retrieved from the databases, which were screened using Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA). The Second and Fifth authors screened the articles and chose the ones to be included in the study. Initially, they used Rayyan software to identify duplicate records and ineligible articles based on the title, and those articles were removed for different research areas, so a total of 393 articles were excluded. After the identification process, the 467 identified articles were screened by the fifth and the third authors by carefully reading the abstracts of each article. It excluded 373 articles that did not meet the eligibility criteria (Table 1). Subsequently, 94 articles were included for abstracts and full paper reading and a total of 56 articles were selected for full-text screening. The full text screening led to the exclusion of another 38 articles that did not meet the requirements. Finally, out of the 56 articles, only 20 articles were selected for the study. Figure 1 explains the PRISMA flowchart and the PICO table explains the details pertaining to the selected studies.

Figure 1: PRISMA flow chart for selection of articles (Page MJ. et al., 2021)

Review results

It is a well-known truth that at least once in their lives, Women and Teen Girls will be subjected to violence (Ellsberg, 2006; Rees et al., 2011; Peterman, et al., 2015). Women and Teen Girls who have been subjected to violence are more susceptible and are more likely to be victims of violence again in the future (Rees et al., 2011; Miller et al., 2011; Peterman et al., 2015). Gender-based violence has an impact on Women and Teen girls' physical and emotional health (Miller et al., 2011; Siddiqui et al., 2013; Sahoo et al., 2015). Several efforts and activities have been made by the government, non-governmental organizations, and other international bodies to protect the well-being of Women and Teen Girls. The following sections thematically narrate the findings of this study.

Prevalence of sexual forms of Gender-Based Violence

'Any form of sexual activity, including attempts to engage in sexual acts, unwelcome sexual remarks or approaches, or actions involving coercion or trafficking, that are aimed towards a person's sexuality by any individual, regardless of their relationship to the victim, in any environment, such as home or workplace,' according to the World Health Organization (WHO). According to RAINN (Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network), a sexual assault occurs every 68 seconds in the United States (National et al., 2019). The majority of sexual assaults occur in or near the victim's home, according to the report (Female Victims of Sexual Violence, 1994 -2010). Approximately 6% of females, including both women and teenage girls, report experiencing sexual assault perpetrated by anyone other than their spouse or romantic partner. Nevertheless, due to the negative social perception associated with this form of violence, it is highly probable that the actual prevalence of non-partner sexual assault is considerably higher (WHO, 2021). Adolescent females are the most vulnerable to forced sex (forced sexual intercourse or other sexual activities) by a current or previous husband, partner, or boyfriend in the great majority of nations. According to data from 30 nations, barely 1% of people have ever sought professional assistance (UNICEF, 2017; Gupta, 2014). In most countries with available data, the majority of women and teenage girls seeking help rely on their family and friends, while only a minority seek aid from formal institutions such as the police and health services. According to the United Nations Economic and Social Affairs (2015), only approximately 10% of those seeking assistance reported their issues to the police. A study investigating the correlation between gang participation and reproductive health, as well as the mechanisms by which exposure to childhood, family, and relationship violence can lead to unintended pregnancy, discovered that Latinas who were exposed to interparental violence, childhood physical and sexual abuse, and gang violence were more likely to be involved in unhealthy and abusive intimate relationships (Miller, 2011).

Prevalence of physical forms of Gender-Based Violence

Physical forms of violence encompass various actions such as scratching, biting, pushing, shoving, slapping, kicking, choking, strangling, throwing objects, force-feeding, withholding food, employing weapons or potentially harmful objects, physically restraining by pinning against surfaces, engaging in reckless driving, and other acts that cause harm or pose a threat to an individual. Evidence from the literature used in the study demonstrates that a variety of factors contribute to physical violence, including but not limited to domicile, alcohol intake, and socio-demographic characteristics (Ngonga, 2016; Dery, 2014). Intimate partner violence (IPV) against Women and Teen Girls in the home usually takes the form of physical damage, and Women and Teen Girls with a lifetime history of IPV were more likely to report poor physical health than those who had never experienced IPV (Kamimura, et al., 2014). According to a study done in Ghana's Upper West area, the most prevalent kinds of physical violence include beating, slapping, pushing/punching, and kicking. Participants believed that women and teenage girls of lower socio-economic and educational positions were more likely to be victims of these types of domestic abuse. They also discovered that the relationship between socio-demographic characteristics and domestic violence in Ghana's Upper West Region is due to the gendered manner in which these manifest themselves. Traditional customs and religious beliefs facilitate men with the chance to displace their frustrations onto Women and Teen Girls, primarily through violence, (Dery, 2014). A study conducted among married Women and Teen Girls in Gwalior city has found that domestic violence is prevalent in the city; among the various forms of domestic violence, physical violence is the highest compared to other forms of violence (Giulia, 2014). Women and Teen Girls who experienced physical violence during pregnancy are less likely to get prenatal care during their pregnancy compared to those who did not experience physical violence (Koski, 2011)

Prevalence of Psychological Forms of Gender-Based Violence

Psychological violence refers to the act of subjecting the victim to humiliation, either personally or in public, by the perpetrator. The offender dominates the victim's autonomy and ability to obtain knowledge (Siddiqui, 2013). Women and adolescent females who have experienced intimate partner violence (IPV) are more prone to reporting diminished physical and emotional well-being. However, women and teenage girls who are victims of intimate partner violence (IPV) often refrain from seeking assistance or instead depend on informal sources of support. The experience of Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) was explicitly linked to anxiety, pain, despair, physical symptoms, as well as reduced levels of social health and self-esteem (Kamimura et al., 2014; Sudha, 2013). Insufficient sanitation facilities impose psychosocial strain on women and adolescent girls, manifesting in three main categories: environmental, social, and sexual stresses. Insufficient sanitary infrastructure has a more significant impact on the psychological and physical health of women and girls, as evidenced by Sahoo (2015). Throughout their lifetime, individuals may experience various types of gender-based violence (GBV) sequentially, leading to the development of many mental disorders. The connection between these two domains is expected to be intricate. Gender-based violence (GBV) can lead to mental disorders, while mental disorders can make women and teenage girls more susceptible to experiencing additional GBV (Rees, 2011).

Prevalence of economic forms of Gender-Based Violence

It is an integral part of domestic abuse against Women and Teen Girls (Adams et al., 2020). A significant percentage of Women and Teen Girls are affected by economic violence (Postmus et al., 2020). Its effects include jeopardizing Women's and Teen Girls' economic stability and posing a danger to self-sufficiency. It can lead to Women and Teen Girls being forced to live on a strict allowance or beg for money, making it a gendered issue (Schrag et al., 2020). An empirical study that surveyed 398 Women and Teen Girls in New Zealand about their experiences and effects of economic abuse found that the most common forms of violence reported by Women and Teen Girls were 1). loss of financial decision-making power, 2). no right to input, 3). disregard for Women and Teen Girls' financial wants and needs, 4). deprivation of essentials, and 5). deception and blame (Jury et al., 2017). Women and Teen Girls in India who are economically disadvantaged experience a lack of economic independence that is caused not just by their class and gender but also by their religion (Ohlan, 2020). A study in India that looked at the extent of economic violence against minorities showed that evidence of economic violence in the form of job sabotage experienced by Muslim Women and Teen Girls is more significant than other forms of economic violence, such as economic dispute (Ohlan, 2020).

Prevalence of domestic violence

One in every three Women and Teen Girls has been beaten, coerced into sex, or abused by a member of her own family at some point in their lives (Heise et al., 1999). Domestic violence is the most common yet relatively hidden and ignored form of violence against Women and Teen Girls and girls. Hitting or beating a wife is not only expected, but men justify it with a variety of excuses (Sudha, 2013). Amid the COVID-19 pandemic, the number of Women and Teen Girls in India contacting the National Commission for Women and Teen Girls to report domestic abuse and harassment has increased significantly in 2021 compared to 2020. (Times of India, 2022). The commission received 30,865 complaints, with 72.5 per cent of them falling into one of three categories: securing their right to live in dignity (36%), protection from domestic abuse (21.6%), and harassment of married Women and Teen Girls, including for dowry (15 per cent). Domestic violence can be caused by cultural, political, economic, and legal factors (Heise et al., 1994; Sudha, 2013; Siddiqui, 2013). Domestic abuse is frequent in Gwalior, according to a survey performed among married Women and Teen Girls in the city. Of the 144 participants, 68 had reported experiencing some domestic violence (Mishra, 2014).

Low threshold community-based support system for Women and Teen Girls

Gender-Based Violence in community and workplace

Women and Teen Girls are particularly vulnerable to several human rights breaches as a result of physical and verbal abuse, forced labour and slavery, human trafficking, kidnapping, nudity parading, and sexual assault, including rape and gang rape. An empirical study conducted among Dalit Women and Girls in Rajasthan revealed that they face inconceivable oppression not only on the basis of gender but also on the basis of caste. Such atrocities can prevent Dalit Women and Teen Girls and their community from enjoying their human rights (Seema, 2021). Many female employees are susceptible to workplace violence, which has been noted as a global concern. Working Women and Teen Girls who are harassed at work may find themselves unable to continue working and, as a result, may be forced to leave the firm or lose their productivity (Siddiqui, 2013; Dehghan-Chaloshtari, 2020; Sudha, 2013; Kaushal, 2015). According to a study on the causes and characteristics of workplace violence against nurses, every nurse faces violence at some point throughout their employment. The most prevalent kinds of violence are intimidation and bullying, with patients functioning as the primary perpetrators (Dehghan-Chaloshtari, 2020). In India, a study of violence against educated and illiterate Women and Teen Girls indicated that educated Women and Teen Girls are less likely to be subjected to physical violence, but they are more likely to be subjected to psychological abuse (Dery, 2014; Kaushal et al., 2015; Dehghan-Chaloshtari et al., 2020). Women and Teen Girls who are victims of domestic abuse in their homes are under-reported, often because cultural norms prevent them from doing so (Sudha, 2013; Siddiqui, 2013; Gupta, 2014; Dery, 2014; Kaushal, 2015). This high rate of violence against Women and Teen Girls in the community and at work is primarily attributable to a lack of community support for Women and Teen Girls who are victims of abuse (Dehghan-Chaloshtari et al., 2020; Marques et al. 2020; Akhmedshina, 2020). Most Women and Teen Girls who are subjected to domestic abuse by their husbands are powerless to denounce it (Sudha, 2013; Gupta, 2014). Because of the societal and cultural norms and traditions, which vary across the country, Women and Teen Girls are unwilling to file complaints against their family members (Siddiqui, 2013; Gupta, 2014). It would be beneficial for household Women and Teen Girls to be able to quickly access and speak up about their concerns if community health centers could give aid to these victims of abuse (Garca-Moreno, 2015).

COVID-19 and Gender-Based Violence

A novel coronavirus created the COVID-19 pandemic, which affected the lives of a substantial section of the world's population. Since then, countries have started implementing WHO-recommended pandemic-prevention measures such as disease separation, social distancing, etc. As a result, there has been an increase in the number of Women and Teen Girls reporting domestic abuse (Marques et al., 2020; Times of India, 2022). This sudden increase in violence against Women and Teen Girls is due to preventative measures used to combat the pandemic, which has exacerbated concerns such as domestic violence. Some of the key factors are listed below (Kamimura et al., 2014; Peterman et al., 2020; Dery, 2014; Amber, 2020):

a. As a result of stay-at-home regulations, Women and Teen Girls in abusive situations are at much more risk;

b. Economic insecurity, job losses, and overpopulation, which make physical separation hard, are likely to exacerbate interpersonal violence.

c. There was a scarcity of protective support networks.

d. Perpetrators of intimate partner violence may use concerns about COVID-19 to exert greater authority and control over their victims

e. Increased use of alcohol and other drugs may enhance the perpetration of violence

The pandemic scenario and the protocols followed to decrease viral propagation hindered the functioning of community-based support structures for Women and Teen Girls (WHO, 2020; Marques et al., 2020, Peterman et al., 2020). This highlights the need to ensure the continued operation of current support programs and the government's responsibility to take additional steps to reinforce the vulnerable Women and Teen Girls population.

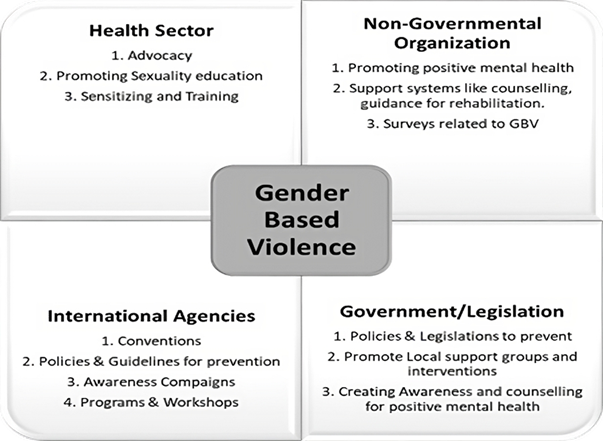

Action and Awareness on Ending Violence against Women and Teen Girls

There are several laws and legislation in place to protect Women and Teen Girls who are victims of Gender-Based Violence. For instance, in India there are both Women and Teen Girls-specific laws such as the Dowry Prohibition Act, the Domestic Violence Act, the Sexual Harassment of Women and Girls at Work Act, and the Indecent Representation of Women and Girls Act, as well as Women and Teen Girls-related legislation such as the Indian criminal code and the Indian Evidence Act. At the international level, treaties such as the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women and Girls, the Declaration on the Elimination of Violence against Women and Girls, and others have been signed. Despite all of these efforts, violence against Women and Teen Girls continues to exist in society (Sudha, 2013; Marques et al., 2020; WHO, 2020). For instance, every third of Indian women aged 15 to 49 years has experienced sexual or physical assault at some point in their lives (Gupta, 2014). When compared to sexual violence by other males, very few incidences of sexual violence by husbands are documented (Heise et al., 1994; Sudha, 2013; Siddiqui, 2013; Gupta, 2014). In India, violence against Dalit Women and Girls is common, yet rarely recorded (Seema, 2021). According to recent data, the frequency of domestic abuse instances reported by Women has grown dramatically throughout the pandemic period (Times of India, 2022). We may deduce that despite being aware of the laws designed to protect them from violence they are less likely to utilize them due to caste, religion, patriarchal dominance, and their belief that males are superior sex to them (Dery, 2014; Ohlan. 2020). Women and Teen girls’ education is on the rise, and the trend is shifting, yet psychological abuse against working Women and Teen Girls persists (Dery, 2014; Kaushal et al., 2015).

Advocacy on violence against Women and Teen Girls (helpline)

Advocacy interventions are designed to directly assist abused Women and Teen Girls by providing them with information and assistance to enable them to access community services. Survivors are often connected to legal, police, housing, and financial services, with many additionally including psychological or psycho-educational help (Garca-Moreno, 2015). At the state, national, and international levels, advocacy on problems of GBV against Women and Teen Girls is common. However, multiple actors must operate at the community level. According to research on domestic violence, effective counseling and behavioral therapies should be provided to both the victim and the offender (Siddiqui, 2013; Sudha, 2013), and community health centers should provide facilities for Women and Teen Girls who are apprehensive about visiting regional centers (Garcia-Moreno, 2015). In India, the Vishaka Guidelines, set forth by the Supreme Court, was a significant step in preventing sexual harassment at work and were subsequently supplanted by the Sexual Harassment of Women and Teen Girls at Work Act (2013). A 16-day campaign against violence against Women and Teen Girls, founded by the Rutgers University Center for Women and Teen Girls’ Global Leadership (CWGL) in the United States, is one of the world's longest-running campaigns (Akhmedshina, 2020). The UN Secretary- General's Campaign to End Violence Against Women and Teen Girls 2008 including a wide variety of civil society were actively involved in the prevention of abuse and the assistance to protect Women and Teen Girls and girls who have been victims of violence, raising awareness and intensifying advocacy. Several additional community-based advocacy efforts have been made, but they have had little influence on the issue. It demonstrates that cooperation at both the international and national levels is essential to find a solution (Akhmedshina, 2020; Emanuele et al., 2020). The Inter-Agency Standing Committee on Gender-Based Violence Intervention in Humanitarian Settings has laid down a set of guidelines (IASC, 2005). This tool aids humanitarian workers in developing a multi-sectoral, coordinated response to gender-based violence in disasters. It provides practical advice on how to ensure that humanitarian relief and protection programs for displaced persons are safe and do not, either directly or indirectly, increase the risk of sexual assault for women and teenage girls. It also specifies what kind of response services should be provided to meet the needs of survivors and victims of sexual assault. It also includes action papers on coordination, assessment, monitoring, human resources, WASH, food, housing, health, education, and minimal preventive and response information. Comprehensive education on sexuality for youth could help the health sector promote gender equality (IASC, 2005; UNDRR, 2021).

Table 2: Summary of selected Health outcomes of Gender-Based Violence

|

Domain |

Disease/injury resulting from violence |

Definition |

|

Injuries |

Any injury inflicted by partner / non-partner |

Disabilities, wounds, bruises, scars, chronic pain, Bodily injuries, Broken bones, Burns, physical trauma. Depressive episodes, self-harm, suicidal behavior, panic disorder, depression, hypertension, cardiovascular diseases, eating disorders, and Drug and alcohol use to cope. |

|

Mental Health |

Unipolar depressive disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder, alcohol use disorder |

<2500 hours |

|

Perinatal Health |

Low birth weight, premature age |

Gestational age <37 weeks |

|

Reproduction Health |

Induced abortions |

Miscarriages |

|

Sexual Health |

HIV / AIDS / Sexual transmitted disease |

Infection with HIV. With or without progression to AIDS Syphilis, chlamydia or gonorrhea. |

Figure 2: Roles of Multiple agencies in combating Gender-based violence.

Source: (IASC, 2005; United Nations, 2008; Siddiqui, 2013; Sudha, 2013; Garca

et al., 2015)

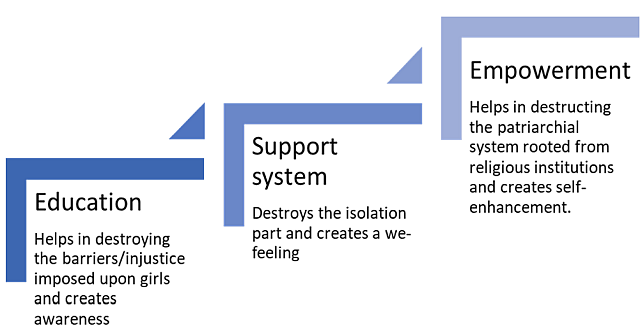

Vocational qualification of Women and Teen Girls working in the informal sector

Economic growth, gender equality and empowerment are critical in advancing gender equity (Harisha, 2020). Women and Teen Girls are more likely to be unskilled than men in rural and urban areas (Dinesha et al., 2016; Harisha, 2020). While education, particularly skill development for girls and Women and Teen Girls, has long been recognized as essential for human and societal development, access to and participation in such fundamental resources has proven difficult (Bhavani et al., 2017; Hartl, 2009). Over 90% of women and teen girls are employed in the unorganized sector (Harisha, 2020). However, Women and Teen Girls’ working conditions in the informal sector are deplorable; most of the time, they are forced to work for meagre wages and have no job security or social security benefits; in addition, working conditions are also unsatisfactory, and one of the main reasons for all of these issues is a lack of skill among Women and Teen Girls (Dinesha et al., 2016; Harisha, 2020). Apprenticeship, on the other hand, often provides fundamental abilities but needs to familiarize individuals with new technology or management skills (Singh, 1992). Thus, there is a need to convert unskilled Women and Teen Girls labor in the informal sector to skilled Women and Teen Girls’ labor, as this aids their economic stability and provides respite from gender-based violence in their homes (Diwakar et al., 2015). Women and Teen Girls’ skill development programs must evaluate HRD and training policies from a gender perspective, as well as local customs and traditions, and be adaptable and flexible to persuade Women and Teen Girls to enroll in the programme (Harisha, 2020).

Furthermore, it is essential to recognize that training and skill development for Women and Teen Girls should extend beyond the conventional objective of imparting technical and managerial abilities. It should also encompass fundamental literacy and numeracy skills, as well as foster critical social and political consciousness, gender awareness, and the improvement of life skills (FICCI, 2014; Diwakar et al., 2015). Women and Teen Girls working in the informal sector in India are untrained, and despite their ability to achieve greater heights, they are prevented from increasing their capabilities. This might be due to familial pressure, patriarchal influence, religion, home responsibilities, etc.

Figure 3: Steps in achieving self-enhancement

Source: (IASC, 2005; FICCI, 2014; Diwakar, & Ahamad, 2015; ICRW, 2017)

Importance of Social Work Professionals

By their unwavering commitment to the principles of social justice, human rights, and empowerment, social workers have the potential to foster a society devoid of gender-based violence. Social workers are integral in the efforts to eliminate gender-based violence (GBV) by engaging in various activities such as prevention, providing support to victims, advocating for policy changes, and empowering communities (Hall., 2007; Masigo et al., 2019). Workshops and awareness campaigns are organized by social work professionals and field practitioners to educate communities about gender-based violence (GBV), advocate for gender equality, and question detrimental gender stereotypes (Kaviti, 2016; Smith, et al., 2022). They also offer counseling and assistance to individuals affected by gender-based violence (GBV), facilitating their access to appropriate resources and actively promoting their rights (Bent-Goodley, 2009; Bettinger-López et al., 2020). Social workers collaborate with policymakers and government agencies to establish GBV prevention and intervention programs.

Additionally, social workers in health settings can conduct research and provide valuable insights to inform policy decisions grounded in evidence-based practices (Young, 1986). In addition, they engage in the facilitation of community dialogues, empower women and adolescent girls to voice their opposition against gender-based violence (GBV), and provide assistance in the establishment of women's organizations to promote reciprocal support and collaborative initiatives (Leburu-Masigo et al., 2019).

Conclusion

This study gives a picture of gender-based violence at home, community, and workplace. Women and Teen Girls are particularly vulnerable gender to violence when compared to males. Recognizing the problem and its gravity across the world, leading international and national organizations have adopted several efforts to combat violence against Women and Teen Girls. Several studies have presented multiple contributing elements, and remedies to gender-based violence. The patriarchal culture, weaker gender roles, caste, religion, social stratification, economic level, and other characteristics are all identified as contributing factors. The majority of the studies listed in this article recommends that the perpetrator of violence should receive competent counseling. Women and Teen girls' health systems, such as community health centers, play a vital role in preserving and defending their interests, as Women and Teen Girls experiencing domestic violence are hesitant to name their husbands as the offenders. If amenities are available in their neighborhood, it will be easy for them to use them. Though all of these solutions are implemented through law and social services, they must be more comprehensive and address the core cause of the problem. From this review, it is evident that in order to eradicate gender-based violence against Women and Teen Girls, the core cause of the problem must be addressed. Through providing education to Women and Teen Girls and skill development opportunities in the workplace, Women and Teen Girls could be empowered to raise their voices against violence and develop knowledge regarding various support systems. It is clear from the compilation of the recommendations from the literature that gender equality and the abolition of gender-based violence must be achieved. Women and Teen Girls should have equal representation in leadership and decision-making authority; targeted measures aimed at Women and Teen Girls should be implemented to protect and stimulate the economy; international cooperation between countries is necessary to eliminate violence against Women and Teen Girls; and support systems for victims of GBV should be available 24*7. By advocating for these measures social work professionals can help create a society where Women and Teen Girls are protected from GBV.

Author’s contribution

Conceptualization SP, Methodology SP, SS, FX.L.LF, HSM, RR; validation SP, SS FXLLF, HSM; data analysis and data synthesis SP, SS, RR; writing- original draft preparation SP, SS writing- review and editing SP KK LR, SS visualization SP, supervision SP all authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received funding from the SAVE organization in Tirupur

Informed consent statement/ Ethical consideration

This study was carried out according to the recommendations of the organization, with written informed consent from all the participants, Ref. no. Dean/SW no/ 09 Dt (22/11/2021). All subjects gave written informed consent in accordance with the declaration of participation.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest

Acknowledgements

On behalf of the research team, we would like to thank the SAVE organization, Tirupur, for their financial support and for initiating the project on "GENDER-BASED VIOLENCE". We want to thank SAVE VOLUNTEERS for helping the team with data collection. We wholeheartedly thank the participants of the study for their valuable input and responses.

References:

Adams, A. E., Greeson, M. R., Littwin, A. K., & Javorka, M. (2020). The Revised Scale of Economic Abuse (SEA2): Development and initial psychometric testing of an updated measure of economic abuse in intimate relationships. Psychology of Violence, 10(3), 268–278. https://doi.org/10.1037/vio0000244

Akhmedshina, F. (2020). Violence against women and girls: A form of discrimination and human rights violations. Mental Enlightenment Scientific-Methodological Journal, 2020(1), Article 34. https://uzjournals.edu.uz/tziuj/vol2020/iss1/34

Andrew, M., Mary, E., & Sarah, B. (2007). Addressing gender-based violence: A critical review of interventions. The World Bank Research Observer, 22(1), 25–51. https://doi.org/10.1093/wbro/lkm003

Bent-Goodley, T. (2009). A black experience-based approach to gender-based violence. Social Work, 54(3), 262–269. https://doi.org/10.1093/sw/54.3.262

Bettinger-López, C., & Ezer, T. (2020). Improving law enforcement responses to gender-based violence: Domestic and international perspectives (Chapter 20). https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3697459

Bhavani, R. R., Sheshadri, S., & Maciuika, L. A. (2017). Addressing the first teachers: Education and sustainable development for children, families and communities through vocational education, technology and life skills training for women and girls. In Children and sustainable development (pp. 319–334). Springer.

Dehghan-Chaloshtari, S., & Ghodousi, A. (2020). Factors and characteristics of workplace violence against nurses: A study in Iran. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 35(1-2), pp. 496–509. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260516683175

Dery, I. (2014). Domestic violence against women and girls in Ghana: An exploratory study in Upper West Region, Ghana. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/281093825

Diwakar, N., & Ahamad, T. (2015). Skills development of women and girls through vocational training. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/290691361

Ellsberg, M. (2006). Violence against women: A global public health crisis. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, pp. 34, 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1080/14034940500494941

FICCI. (2014). Reaping India's promised demographic dividend — industry in the driving seat. Ernst & Young LLP.

García-Moreno, C., Hegarty, K., d'Oliveira, A. F., Koziol-McLain, J., Colombini, M., & Feder, G. (2015). The health system response to violence against women and girls. The Lancet, 385(9977), 1567–1579. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61837-7

GBVIMS. (2006). Gender-based violence classification tool. http://gbvims.com/wp/wp-content/uploads/Annex-B-Classification-Tool.pdf

Gupta, A. (2014). Reporting and incidence of violence against women and girls in India. https://riceinstitute.org/research/reporting-and-incidence-of-violence-against-women-and-girls-in-india/

Hall, N. (2007). We care, don't we? Social Work in Health Care, pp. 44, 55–72. https://doi.org/10.1300/J010v44n01_06

Hartl, M. (2009). Technical and vocational education and training (TVET) and skills development for poverty reduction–do rural women and girls benefit?

IASC. (2005). Guidelines for gender-based violence interventions in humanitarian settings. https://interagencystandingcommittee.org/system/files/2021-09/IASC%20Common%20Monitoring%20and%20Evaluation%20Framework%20for%20Mental%20Health%20and%20Psychosocial%20Support%20in%20Emergency%20Settings-%20With%20means%20of%20verification%20%28Version%202.0%29.pdf

Kamimura, A., Ganta, V., Myers, K., & Thomas, T. (2014). Intimate partner violence and physical and mental health among women and girls utilizing community health services in Gujarat, India. BMC Women's Health, 14, Article 127. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6874-14-127

Kaushal, D. V. (2015). Impact of domestic violence on working life of females: A survey of Himachal Pradesh University Shimla. https://www.academia.edu/39985141

Kaviti, L. (2016). Impact of the Tamar communication strategy on sexual gender-based violence in Eastern Africa. International Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences, 2, pp.492–514.

Koski, A. D., Stephenson, R., & Koenig, M. R. (2011). Physical violence by partner during pregnancy and use of prenatal care in rural India. Journal of Health, Population, and Nutrition, 29(3), 245–254. https://doi.org/10.3329/jhpn.v29i3.7872

Leburu-Masigo, G., Maforah, N., & Mohlatlole, N. (2019). Impact of victim empowerment programme on the lives of victims of gender-based violence: Social work services. Gender and Behaviour, 17. https://doi.org/10.4314/gab.v17i3

Marques, E. S., Moraes, C. L., Hasselmann, M. H., Deslandes, S. F., & Reichenheim, M. E. (2020). Violence against women and girls, children, and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic: Overview, contributing factors, and mitigating measures. Cadernos de Saúde Pública, 36(4), Article e00074420. https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-311X00074420

Miller, E., Levenson, R., Herrera, L., Kurek, L., Stofflet, M., & Marin, L. (2012). Exposure to partner, family, and community violence: Gang-affiliated Latina women and girls and risk of unintended pregnancy. Journal of Urban Health, 89(1), 74–86. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-011-9631-0

Mishra, A., Patne, S. K., Tiwari, R., Srivastava, D. K., Gour, N., & Bansal, M. (2014). A cross-sectional study to find out the prevalence of different types of domestic violence in Gwalior city and to identify the various risk and protective factors for domestic violence. Indian Journal of Community Medicine, 39(1), 21–26. https://www.ijcm.org.in/text.asp?2014/39/1/21/126348

Mugyenyi, C., Nduta, N., Ajema, C., Afifu, C., Wanjohi, J., Bomett, M., Mutuku, C., & Yegon, E. (2020). Women and girls in manufacturing: Mainstreaming gender and inclusion. International Center for Research on Women and Kenya Association of Manufacturers.

NCRB. (2021). Crime in India – Statistics Volume 1. National Crime Records Bureau. https://ncrb.gov.in/uploads/nationalcrimerecordsbureau/custom/1696831798CII2021Volume1.pdf

Ngonga, Z. (2016). Factors contributing to physical gender gender based violence reported at Ndola Central Hospital, Ndola, Zambia: A case-control study. Medical Journal of Zambia, 43(2), 66–75.

Ohlan, R. (2021). Economic violence among women and girls of economically backward Muslim minority community: The case of rural North India. Future Business Journal, 7, Article 19. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43093-021-00074-9

Peterman, Potts, O'Donnell, Thompson, Shah, Oertelt-Prigione, & van Gelder. (2020). Pandemics and violence against women and girls and children (CGD Working Paper No. 528). Center for Global Development. https://www.cgdev.org/sites/default/files/pandemics-and-vawg-april2.pdf

Peterman, A., Bleck, J., & Palermo, T. (2015). Age and intimate partner violence: An analysis of global trends among women experiencing victimization in 30 developing countries. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 57(6), 624-630. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.08.008

Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., ... Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372, Article n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

Rees, S., Silove, D., Chey, T., Ivancic, L., Steel, Z., Creamer, M., Teesson, M., Bryant, R., McFarlane, A. C., Mills, K. L., Slade, T., Carragher, N., O'Donnell, M., & Forbes, D. (2011). Lifetime prevalence of gender-based violence in women and the relationship with mental disorders and psychosocial Function. JAMA, 306(5), 513–521. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2011.1098

Sahoo, K. C., Hulland, K. R., Caruso, B. A., Swain, R., Freeman, M. C., Panigrahi, P., & Dreibelbis, R. (2015). Sanitation-related psychosocial stress: A grounded theory study of women across the life-course in Odisha, India. Social Science & Medicine, 139, 80–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.06.031

Seema, M. (2021). Caste-based discrimination and violence against Dalit women and girls in India. Quest Journals: Journal of Research in Humanities and Social Science, 9(8), Article 2. https://www.questjournals.org/jrhss/papers/vol9-issue8/Ser-2/G09084654.pdf

Siddiqui, A. B. (2013). Domestic violence on women in India. https://www.academia.edu/5450574/

Singh, B. R. (1992). Training for employment: Some lessons from experience. Journal of Educational Planning and Administration, 6(2).

Smith, K., Hurst, B., & Linden-Perlis, D. (2022). Using professional development resources to support the inclusion of gender equity in early childhood teaching and curriculum planning. Gender and Education, 35, 199–214. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540253.2022.2142530

Sudha, C. (2013). Domestic violence in India. https://www.scribd.com/document/221917107/21

UNFPA. (2019). The inter-agency minimum standards for gender-based violence in emergencies programming. https://unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/19-200_Minimun_Standards_Report_ENGLISH-Nov.FINAL_.pdf

UNHCR. (2018). Guidance note: Responding to sexual violence against males and engaging men and boys in preventing sexual and gender-based violence. https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/66785.pdf

UNICEF. (2014). International day of the girl child UNICEF fact sheet. https://www.unicef.org/mena/media/8151/file

UNICEF. (2017). A familiar face: Violence in the lives of children and adolescents. https://www.unicef.org/media/48671/file

UNICEF. (2019). Fast facts: 10 facts illustrating why we must #EndChildMarriage. https://www.unicef.org/eca/press-releases/fast-facts-10-facts-illustrating-why-we-must-endchildmarriage

United Nations. (2015). The world's women 2015: Trends and statistics. https://unstats.un.org/unsd/gender/downloads/WorldsWomen2015_report.pdf

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. (2020). UNHCR policy on the prevention of, risk mitigation and response to gender-based violence. https://www.unhcr.org/publications/brochures/5fa018914/

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. (2021, November). 3 matters - United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. https://www.unodc.org/documents/data-and-analysis/statistics/crime/UN_BriefFem_251121.pdf

United Nations. (2019). Conflict-related sexual violence - Report of the United Nations Secretary-General. https://www.un.org/sexualviolenceinconflict/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/report/conflict-related-sexual-violence-report-of-the-united-nations-secretary-general/2019-SG-Report.pdf

Villanueva, L., & Ballester, A. (2014). Psychological assessment of gender-based violence (GBV) crimes by the Millon Clinical Multiaxial Inventory-III (MCMI-III). https://core.ac.uk/reader/61452477

World Health Organization. (2020). Addressing violence against children, women and older people during the COVID-19 pandemic: Key actions (BREAD Policy Brief). http://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep28197

World Health Organization. (2021). Violence against women prevalence estimates: Global, regional and national prevalence estimates for intimate partner violence against women and global and regional prevalence estimates for non-partner sexual violence against women. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240022256

World Health Organization. (2021). Violence against women. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/violence-against-women

Young, C. (1986). Social work roles in collaborative research. Social Work in Health Care, 11(4), 71–81. https://doi.org/10.1300/J010v11n04_06

Author´s

Address:

Sigamani Panneer

Centre for the Study of Law and Governance

Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi-110067 and D.Litt. Fellow, Department of

Social Work, Assam University (A Central University), Silchar, Assam

sigamani@mail.jnu.ac.in

Author´s

Address:

Saranya Sundarraju

Department of Social Work

School of Social Sciences and Humanities, Central University of Tamil Nadu,

Thiruvarur, 610005

saranyasundarraju@gmail.com

Author´s

Address:

F.X. Lovelina Little Flower

Department of Social Work

Bharathiar University, Coimbatore 641046, Tamil Nadu

fxlovely@gmail.com

Author´s

Address:

Hilaria Soundari Manuel

Department of Applied Research

Gandhigram Rural Institute, Gandhigram, Dindigul 624302, Tamil Nadu

hilariasoundari@gmail.com

Author´s

Address:

R. Revanth

Research Scholar

Department of Social Work, Bharathiar University

Coimbatore 641046, Tamil Nadu

revathajay1@gmail.com