Poly-Victimisation and Health Risk Behaviors amongst Street Children in Zimbabwe

Constance Gunhidzirai, University of Botswana

Leila Patel, University of Johannesburg

Abstract & Keywords: This paper explores how poly-victimisation affects health and influences street children's behavior in Harare Metropolitan Province in Zimbabwe. There are many studies on street children in Zimbabwe, but little is known about how multiple forms of violence affect their physical and mental health. The study has problematized poly-victimisation from the theoretical lens of psychoanalytic theory, as the traumatic events experienced by street children can have a negative impact on their physical and mental health. A survey in the form of a questionnaire was used to gather data from 202 street children between the ages of 6-18 years who were purposively selected for this study. The findings indicated that most street children are experiencing physical, sexual, emotional and psychological abuse. This drives them to indulge in substance use, alcohol consumption, suicide idealism, and risky sexual activities. Recommendations for this study have been derived from the findings that seek to improve social work policy in Zimbabwe.

Keywords: Poly-victimisation; Health; Violence; Street children; Vulnerability

Introduction and Background of the Study

The nature of street children is heterogeneous, which makes it difficult to define their population. The United Nations International Children Emergency Fund (UNICEF) (2006) divides street children into three categories, which are children on the streets - who have limited contact with their families or relatives; children on the street – who have contact with family and are sometimes living on and off the streets; and abandoned children – who have no contact with their families Assaw (2019) and Palermo et al., (2019) explain that street children refer to boys or girls under 18 years who live on the streets or whose source of livelihood is on the street where they work without being supervised by an adult. According to Varghese (2017), street children are not widely abused in developed countries, where few children roam the streets. The insignificant number of children on the streets are those who move around with their homeless families and whose main reasons for being on the street are unemployment and failure to pay housing bonds (D’Sa et al., 2021).

Street children are often malnourished and subjected to health issues and various forms of abuse while living on the streets. Street children constitute a major social challenge for governments, welfare organisations and society because their plights adversely affect their physical and mental health (Gabriel, 2021). In Zimbabwe and other African countries, street children are exposed to various forms of violence on the streets. According to Finkelhor, Ormrod, Turner & Hamby (2005), poly-victimisation is the occurrence of multiple forms of victimisation, which include all forms of abuse such as emotional, sexual, physical maltreatment, bullying, drug use, neglect, physical abuse and witnessing community violence. Studies by Tyler & Raj (2019) and Cerna-Turoff et al. (2021) revealed that children on the streets, whether due to being orphaned, abandoned, or neglected, or those from poverty-stricken households, are vulnerable to victimisation. These children are exposed to all forms of violence on the street, such as drug abuse, infectious ailments, criminal activities, and HIV/AIDS (Chimdessa & Cheira, 2018). Such challenging street conditions expose children to violence, which can affect their social growth and economic development.

Studies done in Zimbabwe by Ndlovu & Tigere (2022), Mhlanga (2021), and Manungo (2018) investigated the phenomenon of street children and their gender dimension, while little is known about the effects of victimisation on their health. Pankhurst, Negussie & Mulugeta (2016) reported that children's life-changing events and traumatic experiences on the streets negatively affect their health and psychological well-being. This often leads to risky behaviors such as substance abuse, antisocial activities, and even suicidal thoughts (Vivek et al.,2020). Furthermore, when children take to the streets to escape a violent family situation, they experience double victimisation from their childhood experiences in the family setting and on the streets. This study seeks to address three major research questions viz., a). what forms of poly-victimisation are faced by street children in Harare Metropolitan Province? b). what health risks street children in Harare Metropolitan Province are experiencing? c). what services are being provided by DSD to address violence faced by street children in Harare Metropolitan Province?. Based on the findings this study argues that the multiple forms of violence experienced by street children negatively affect their health and behavior.

This study draws from the Psychoanalysis Theory of Sigmund Freud (Freud, 1949), who studied hysteria, traumatic neuroses, abuse, and disorders of unknown aetiology (Freud, 1991: Laplanche & Pontalis, 1973). Freud contended that childhood trauma and repressed feelings can have a significant impact on the lives of individuals. In this study, street children were affected by instinctual forces, early childhood experiences and various forms of abuse that were repressed with the potential of affecting their health and shaping risky behaviors. In Zimbabwe, street children are experiencing multiple mental health issues emanating from their past and present life experiences. This causes street children to be irrational, experiment with substances and indulge in unplanned multiple sexual relationships. In support, Barlow & Durand (1995, p.25) concurred that when individuals are not guided by rational decisions, they are “filled with fantasies and preoccupations of sex, aggression, selfishness and envy”. This indicates that street children are in dire need of psychosocial interventions to help them deal with their past and present trauma and violence experienced on the streets. The psychoanalysis theory fits into this study as street children have repressed thoughts and experience traumatic events that affect their health and influence risky behaviours. The Psychoanalysis theory emphasises that childhood experiences and traumatic events such as sexual abuse, when repressed, have a negative effect on the mental health of a person. This theory is relevant to this study as it provides insights into the exploration of the different types of acts of violence faced by street children and their impact on attaining physical and psychological growth in Harare Metropolitan in Zimbabwe.

Nature and complexities of the street environment

Globally children are considered to be a vulnerable group. Several international and local welfare organisations operating in the humanitarian and welfare space agree that children are the most valuable resources in the community as they contribute to 33 per cent of the world’s population (Savarkar & Das, 2019). However, children on the streets are common in developing continents such as Africa, Asia, and Latin America (John et al., 2019). In developing countries, factors such as increased poverty and vulnerability, victimisation, child neglect and maltreatment, death of parents, parental divorce, natural calamities, and child violence have driven children to the streets (Fantahun & Taa, 2022; Chimdessa & Cheira, 2018). Therefore, they are classified as “street children” because they spend most of their time on the streets (Ayenew et al., 2020). This shows that street children need care and protection in a volatile street environment.

The exact number of street children across the globe cannot be estimated due to evolving patterns of urbanisation and changes in the economic and political environment (Yhaya, 2018). The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNDC) (2020) estimated that around 100-150 million children are on the streets worldwide. According to the Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency (2022), the population of Zimbabwe is estimated to be around 15.334,076 million people. Mwanyekondo (2020) revealed that the exact number of children living and working on the streets of major cities, such as Harare, Chinhoyi, Bulawayo, Gweru, and Mutare, is unknown. UNICEF (2021) observed that since the onset of COVID-19, the number of children working in sub-Saharan countries has increased by 160 million because of job losses and retrenchments of the breadwinners. Such unprecedented change in economic statutes of the family head results in street children being vulnerable to exploitation and physical ailments due to the strenuous jobs they participate in their quest to survive in the streets.

The presence of children on the street is a challenging social phenomenon for welfare institutions and governments worldwide because it hinders the well-being of the children and society at large (Hassen & Manus, 2018; Yhaya, 2018). Studies by Ogan & Ogan (2021) and Gabriel (2021) reported that child neglect, maltreatment, abuse, increased household poverty, death of parents and divorce of parents are factors that drove children onto the streets. Street children, hence, perceive the street environment as a safe place to gain financial independence, economic opportunities and peace of mind (Savarkar & Das, 2019). However, the street environment poses more harm than the anticipated benefits, as street children are exposed to multiple forms of violence.

The study of Vivek et al., (2020) revealed that on the streets, street children face difficulties accessing necessities such as nutritious food, clean water, clothing, proper sanitation, and other vital needs for their well-being. Such unfortunate plights encountered by street children call for governments, as primary custodians of children, to help uphold children's rights to necessities. Owing to the volatility of the street environment, children in many African countries experience various forms of violence such as physical, exploitation, sexual, torture and emotional (Nathan & Fratkin, 2018). In most cases, this violence goes unreported for fear of being re-victimised by law enforcement officials for staying on the streets (Gwanyemba et al., 2016). Contrary to developed countries, where homeless children or families receive welfare services such as grants, subsided houses and boarding houses to minimize their vulnerabilities, in developing countries, street children are deprived of all facets of their well-being (Ogan & Ogan, 2021). The failure of many developing countries to cushion street children from all forms of danger points to weaknesses within governments’ social protection systems; hence a robust state intervention is required to ensure the rights and welfare of children are upheld.

Poly-victimisation and healthy risk behaviors

Street children are experiencing various forms of violence, which affect their health. UNICEF, (2020) estimated that one billion children are victims of different forms of violence each year in settings such as family, community, institutional care centers, schools, and streets. These children are categorised as children in difficult circumstances. In Ethiopia, street children are experiencing the worst forms of multiple violence, termed poly-victimisation (Panhurst, 2019). For street children, poly-victimisation is appalling because it affects all facets of their lives. The studies done by Le et al., (2018); Finkelhor et al. (2005) and Hillis et al. (2017) define poly-victimization as violence such as physical, bullying, sexual and emotional experiences by and exposure to family violence or people in society. Gabriel (2021) explains that children who see their parents being physically abused by an intimate partner are likely to be perpetrators of physical abuse. This is evidenced by street children who abuse others on the streets (Ayenew et al., 2020). The analysis of these studies has shown that multiple forms of violence are interlinked, share a common root cause, and coexist as one form can lead to another, leading to a cycle of violence, especially for children on the streets.

There are various categories of perpetrators that abuse children on the streets. Studies by D’sa et al., (2021) and Tyler & Schmitz (2018) revealed that street children are being victimised by street leaders, members of the public, and government officials. The most common violence experienced by street children is physical and sexual. According to data gathered from twenty-four countries, the prevalence of sexual violence against children ranges from 8 per cent to 31 per cent for girls and 3 per cent to 17 per cent for boys (UNICEF, 2020). These statistics show that girls are more vulnerable to sexual violence as compared to boys.

The various forms of violence experienced by children are detrimental to their mental well-being. In developed countries, half of the people with mental health issues start before the age of 14 years, among homeless children and suicide is regarded as the third most common cause of mortality (Varghese, 2017). This shows the correlation between victimisation and mental issues. Drawing from this study it is affirmed that in most developed countries, mental health is ranked high on public policy, contrary to developing countries, where it is often ranked low compared to physical health issues (Hillis et al., 2016). This shows that governments in developing countries need to improve social protection and public policies that safeguard the welfare of street children to help them with mental health issues, among other societal ills.

Social policies for children

The increase in the number of children exposed to multiple forms of violence led to the implementation of child protection policies around the globe. Many countries ratified the Convention on the Rights of Children, which means they agreed to uphold and advance children's rights in their countries (Ayub & Rasoo, 2017). The Convention stipulates that every child has a right to be free from violence and to the best physical and mental health (OHCHR, 1989). Similar commitments were also made in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, goal three, which aims to promote physical and mental well-being and end all forms of abuse (United Nations, 2015). According to Mwanyekondo (2020), the Convention on the Rights of Children in countries such as Zimbabwe, Tanzania, India, Cambodia, Somalia, Nigeria and Zambia have not successfully upheld the rights of street children. A study by Ndlovu & Tigere (2022) showed that social protection intervention in Zimbabwe is not being implemented with adequate accountability, resulting in street children being excluded as beneficiaries of government welfare services. This requires state intervention in which social welfare policies must be amended to reflect inclusivity with specific reference to the needs of street children.

Child welfare policies in Zimbabwe

The Zimbabwean government has implemented several policies to protect children and uphold their rights. The Children’s Protection and Adoption Act (Chapter 5:06 of 1996) was implemented by the government to alleviate the conditions of vulnerable children and secure their well-being. This Act advocates for preventing child maltreatment, child labour, exploitation, and violence (Ndlovu & Tigere, 2022). Under this Act, all orphans, disabled, abandoned, children with chronic diseases, and street children were categorized as children in difficult circumstances (Gunhidzirai & Tanga, 2020). However, this Act has its limitations, as the number of street children is continuously increasing, and the Department of Social Development (DSD) has limited human and financial resources to support street children (Mwanyekondo, 2020). Noting the plights facing street children in Zimbabwe, it can be argued that the Children’s Protection and Adoption Act is ineffective in addressing challenges experienced by vulnerable children.

The government of Zimbabwe implemented the Social Welfare Assistance Act 1988 (Act 10 of 1988) (Cap. 17:06), which sought to provide social assistance to vulnerable groups. This led to the implementation of social protection programmes such as child adoption, institutional care, the Basic Education Assistance Module (BEAM) and free treatment to alleviate child poverty and vulnerability (Gunhidzirai & Tanga, 2020). Despite implementing these programmes, street children lack access to welfare services as they fail to meet the criteria to qualify as beneficiaries due to the absence of a physical address, birth certificates and guardians (Ndlovu & Tigere, 2022). To effectively address some of the needs of street children, the Social Welfare Assistance Act 1988 (Act 10 of 1988) (Cap. 17:06), needs to be revised to leverage access of street children to state welfare services.

Methods

The study's aim was to explore how poly-victimisation affects health and influences street children's behavior in Harare Metropolitan Province in Zimbabwe, using the psychoanalysis theory. The study site was Harare Metropolitan Municipality because it is surrounded by suburbs such as Chitungwiza, Epworth and Highfields. According to studies done by Chipenda (2017) and Chikoko et al. (2018), the above dormitory towns are characterised by high levels of poverty and unemployment, which drive children to work or live on the streets. The research design which underpinned this study is exploratory. Exploratory studies investigate a phenomenon that is not clearly defined and are employed to develop initial ideas and insights (Neuman, 2014).

Respondents of this study were children living in the streets, chosen using a purposive sampling technique to recruit the most appropriate respondents. A total of 202 participants were recruited for the study using the inclusion criteria of street children aged between 15 and 18 years living on the streets in the Harare Metropolitan Province.

The data-collection method used for this study was a survey that gathered data from street children. Three research assistants distributed the questionnaires in public spaces that included the Methodist Church, Harare Gardens, the Anglican Church, Fourth Street and the Copacabana bus terminus in the Harare Metropolitan Province. A descriptive analysis was used to analyse the data gathered. The data were coded in Excel and run on the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) Version 26.

Ethical Considerations

According to Neuman (2014), ethics are moral principles that guide research practice and clarify the boundary between ethical and unethical behaviour towards the participants of a study. The researcher obtained ethical clearance (Reference Number: TANO11SGUN01) from the Research Ethics Committee of the University of Fort Hare. Furthermore, the researcher was granted permission from the Head Office of the Department of Social Development (DSD) to interview street children of different age groups in the Harare Metropolitan Province because most of them had no parents or guardians on the streets.

In accordance with the principle of informed consent, the researcher explained the purpose and objectives of the study to the street children. Those who agreed to be part of this study signed the informed consent form. To uphold the principle of voluntary participation, the children were informed of their rights to withdraw from the study at any point without facing any consequences. Also, the researcher explained the principle of confidentiality and assured the children that the information gathered was not to be shared with any other persons. Furthermore, the researchers maintained confidentiality by using codes to conceal the names of the participants while presenting data. This study may have invaded the private lives of street children as it explored challenges faced in the informal sector. Owing to the sensitivity of this study, the street children who were affected psychologically were provided assistance at the DSD.

Results

This section reports on the findings derived from the children based in Harare Metropolitan Province. The findings are presented under three themes viz., violence faced by street children, health risks behavior faced by street children and social welfare services which sought to respond to the research questions of this study.

Violence faced by street children.

One of the research questions in this article was to find out the types of violence experienced by street children in Zimbabwe. This section depicts the responses of street children on the types of violence experienced, perpetrators of the violence and whether they were exposed to family or community violence.

Types of violence faced by street children.

The study’s findings indicated that street children face different forms of violence. Their response pertaining to the forms of violence is reported below.

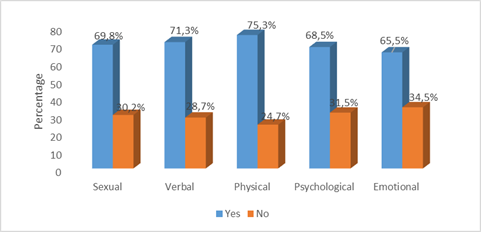

Figure 1: Types of violence

Figure 1 shows 75.3% of the respondents had experienced physical violence, and 71.3% had experienced verbal violence. Furthermore, 69.8% of had experienced sexual violence. In addition, 68.5% of street children have experienced psychological violence. Lastly, 65.5% of street children have experienced emotional violence.

Perpetrators of violence

Various perpetrators are victimising children who stay on and off the streets. The figure below shows the responses of the street children.

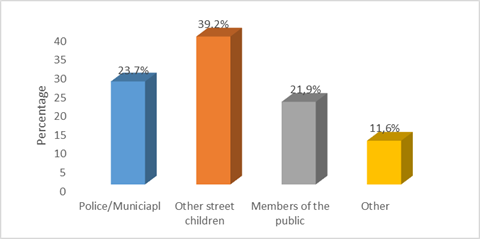

Figure 2: Perpetrators of violence

Figure 2 above reported that other street children were victimising 39.2% of the respondents and 23.7% of the sampled street children were victimised by police or municipal officials. On the other hand, 21.9% were victimised by members of the public. Lastly, 11.6% of were victimised by others (refused to name the perpetrators).

Health risks behavior faced by street children.

Street children are experiencing various mental and physical ailments due to exposure to various forms of violence. This section elaborates on street children's mental and physical challenges, such as having multiple sex partners, suicidal thoughts, mental health problems, STDs, STIs and substance abuse.

Multiple sex partners

The street environment exposes street children to engage in sexual intimacy for various reasons such as street protection, drug influence, commercial basis, and/or due to rape. The figure below shows the responses of street children when asked if they have engaged in multiple sex partners on the streets.

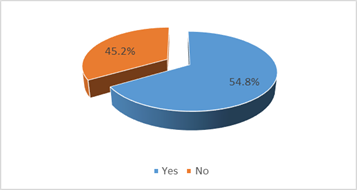

Figure 3: Multiple sex partners

Figure 3 above indicates that 54.8% of the respondents had indulged in sex with multiple sex partners and 45.2% did not have multiple sex partners.

Substances abuse

The findings showed that the various forms of violence experienced by street children drove them to indulge in substance abuse. The illustration below depicts the various substances being abused by street children.

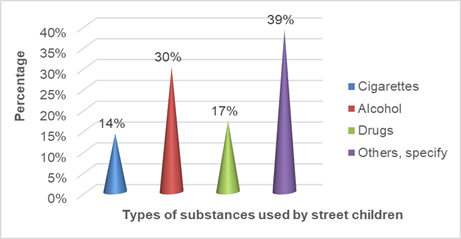

Figure 4: Substance abuse

Figure 4 shows that 39% of the respondents used other substances, such as stimulants, prescription drugs and heroin. In addition, 30% consumed alcohol, and 17 % agreed that they used drugs. Lastly, 14% smoke cigarettes.

Mental Health Problems

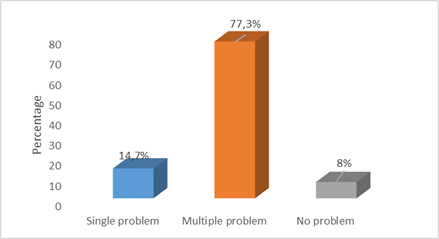

The various forms of violence faced by street children trigger mental health problems. The most common mental health ailments experienced by street children are depression, anxiety disorders, posttraumatic disorder and disruptive behavior. The graph below shows the statistics of the respondents who have experienced such mental health issues.

Figure 5: Mental health problems

Figure 5 indicates that 77.3% of the respondents had experienced multiple mental problems. Furthermore, 14.7% of the participants had experienced single mental health issues. Lastly, 8% of the respondents reported that they had not experienced any mental health issues.

Social welfare services

The DSD is responsible for the well-being of vulnerable children in Zimbabwe. The section below explains the social welfare services such as therapeutic services, Assisted Medical Treatment Orders, treatment facilities and psych-social support that street children receive.

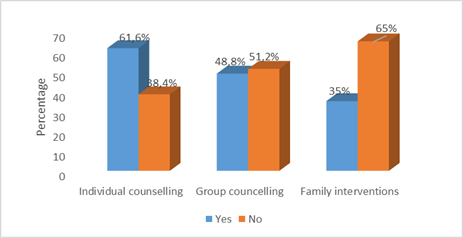

Therapeutic services: One of the roles of social workers is to provide therapeutic services to individuals, groups and families so that they can adapt and function well in society. The figure below shows the responses of street children who received therapeutic services.

Figure 6: Therapeutic services

Figure 6 shows that 61.6% of the respondents had received individual counseling and 38.4% had not. Furthermore, 48.8% had received group counseling and 51.2% had not. Lastly, 35% had received family intervention services, while 65% did not.

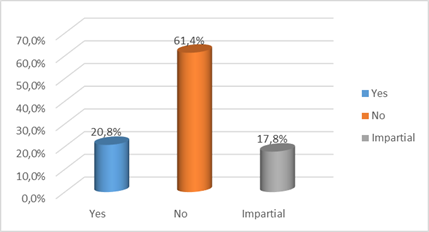

Treatment facilities: Assisted Medical Treatment Order (AMO) is a social welfare service provided by the Department of Social Development in Zimbabwe to individuals who are not able to pay for their medical bills. The figure below shows the responses of street children who received AMO.

Figure 7: Assisted Medical Treatment Order (AMTO)

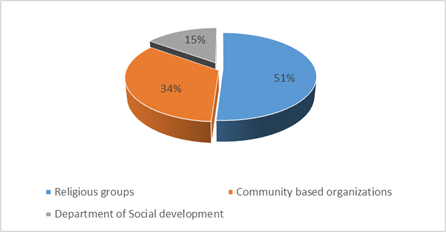

Psycho-social support: Street children face multiple forms of violence, affecting their mental and physical growth and development. The pie chart below depicts the sources from which the respondents received psychosocial support.

Figure 8: Psycho-social support

Figure 8 shows that 51% of the respondents obtained psychosocial support from religious groups, and 34% received assistance from community-based organizations. Lastly, 15% reported that the DSD assisted them.

Discussion

The findings from this study show that street children in Harare Metropolitan Province face various forms of violence, such as physical, psychological, sexual, emotional and verbal. These findings are similar to the findings of other studies done in developing countries like Meinck et al., (2017) and Cerna-Turoff et al. (2021). Vulnerable children who live on the streets and children who are unsupervised in communities are prone to physical, sexual and emotional violence. Tyler & Ray (2019) assert that girls are more vulnerable to violence on the streets than boys because they are physically weaker to fight back against their perpetrators. The violence faced by street children makes life on the streets unbearable and generates a sense of hopelessness, distress and despondency. Laplanche & Pontalis (1973) state that adverse sexual experiences in early childhood and adolescence can induce trauma. Drawing from the psychoanalysis theory, it can further be extrapolated that violence faced by children can adversely affect their mental health and behavioral development. The findings also point to the need for social workers to ensure that children are protected from any forms of violence. In the case of street children, this may be achieved by shifting them to a place of safety.

Further, the findings indicated that street children are experiencing violence from municipal and police officials, members of the public and other street children. The above findings concur with John et al., (2019), which suggest that older persons and law enforcement officials in West Africa are harassing and abusing street children because they refuse to be reintegrated with their families and placed in state care facilities.

The results showed that cigarettes, alcohol, cannabis, stimulants, prescription drugs, and heroin are some of the commonly abused drugs by street children in Harare Metropolitan Province. This is in line with Vivek et al., (2020) and Ayenew et al. (2020) who reported that in India and Eithopia, street children experience issues of adjustment on the streets and are exposed to various forms of violence that drive them to inhale and consume forms of alcohol and drugs that are relatively cheap and easily accessible on the streets. According to studies by Rathoreet al., (2017) and Ayub & Rasoo (2017), substance use is linked to mental health issues such as psychosis, depression, anxiety disorders and disruptive behaviors. The findings of this study also showed that street children experience multiple mental health problems.

Substance use and mental health issues exist in tandem amongst street children in Harare Metropolitan Province. Furthermore, the lack of access to therapeutic intervention can contribute to serious mental health issues including suicidal thoughts. The findings of this study report that only a few street children had access therapeutic interventions. This is consistent with Fantahun & Taa (2022), pertaining to the lack of access to welfare services such as counseling among street children However, a study done by Hillis et al., (2016) in Asia, Africa, and Northern America has shown that street children have formed street families who provide them with informal psycho-social support.

Most street children in this study reported that they had not received any medical voucher under the Assisted Medical Treatment Order (AMTO) to access public hospitals and clinics. The above findings align with Ndlovu & Tigere (2022), who revealed that inadequate funding for social protection programmes such as AMTO has led to poor delivery of health services to vulnerable populations. The findings also show that most street children are accessing treatment at the medical aid society (medical community-based Organization) and other treatment facilities. The findings point to the role of social workers in advocating the rights of street children to have access to social welfare services such as free medical services in public clinics and hospitals.

Conclusion

This paper attempted to understand how poly-victimization affects health and influences the risky behaviors of street children, an under-researched area in Zimbabwe. The conclusions drawn from the findings indicate that street children are experiencing sexual, verbal, physical, emotional and psychological violence on the streets. This has detrimental effects on street children’s physical and mental health. This is shown by street children experiencing anti-social behaviors and multiple mental health issues. Further analysis of the findings revealed that street children are not accessing government welfare services such as therapeutic intervention, AMTO and health facilities, which are vital for enhancing their physical and mental well-being. From a psychoanalysis perspective, the findings bear significant implications as childhood experiences and traumatic events such as sexual, verbal, physical, emotional and psychological violence affect the growth and development of children. Social work interventions bear significant implications in this regard, as locating those in need and extending support is an essential intervention which can be provided only by trained professionals. Social work advocacy and social action by professional social workers can be significant steps in this regard. Hence, advancing equity to children should be a priority for social work professionals in the region.

Recommendations

Based on the findings of this study, the researchers recommend that the DSD in Zimbabwe hold regional dialogues on the effects of violence on street children. This can facilitate greater comprehension of how national policies are implemented and increase the likelihood of interacting with communities to effect change. The researcher recommends that research institutes, and government ministries such as Public Service, Labour and Social Welfare, Health and Childcare and Home Affairs collaborate with Non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs) and Community Based Organizations, on a multi-sectoral and multi-level plan to raise awareness of preventing and addressing violence on vulnerable children by putting a strategic action plan. Lastly, this study also recommends that the DSD develop child-friendly child protection services on violence prevention that should take poverty and structural factors into account that frequently underlie violence against children. Furthermore, greater emphasis must be placed on protecting vulnerable families by providing safety net programmes based on behavioral and social change strategies to assist affected households faced with economic shocks. It is also critical to emphasise the above issues in the Enhanced Social Protection Policy, Children's Protection and Adoption Act (19996) and in the training and deployment of Social Welfare officials in Zimbabwe.

References:

Ayenew, M., Kabeta, T., & Woldemichael, K. (2020). Prevalence and factors associated with substance use among street children in Jimma town, Oromiya national regional state, Ethiopia: A community-based cross-sectional study. Substance Abuse Treatment Prevention Policy, 15(1):61-171.

Ayub, K.D., & Rasoo M. (2017). Substance abuse among street children of Jammu region. Taha International Journal of Medical Science and Clinical Inventions, 4(8):3168 –3171.

Barlow, N., & Durand, M.V. (1995). Abnormal Psychology: An Integrated Approach. New York: Brooks/Cole Publishing Company.

Cerna-Turoff, I., Fang, Z., Meierkord, A., & Yanguela, J. (2021). Factors associated with violence against children in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review and meta-regression of nationally representative data. Trauma Violence and Abuse, 22(2): 219–232.

Chimdessa, A., & Cheire, A. (2018). Sexual and physical abuse and its determinants among street children in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. BMC Pediatric, 18(1):1-8.

D’sa, S., Foley, D., Hannon, J., Strashun, S., Murphy, A.M., & O’Gorman, C. (2021). The psychological impact of childhood homelessness—a literature review. Irish Journal of Medical Science, 190(1):411-417.

Fantahun, T., & Taa, B. (2022). Children of the street: The cause and consequence of their social exclusion in Gondar City, Northwest Ethiopia. Cogent Social Science, 8(1): 105-118.

Finkelhor, D., Ormrod. R., Turner, H., & Hamby, S. (2005). Measuring poly-victimization using the juvenile victimization questionnaire. Child Abuse Neglect, 29(11):1297–1312.

Freud, S. (1991). New Introductory Lectures on Psychoanalysis. London: Penguin Books

Freud, S. (1949). An Outline of Psychoanalysis. London: Hogarth Press.

Gabriel, J. (2021). Listen to the voices of street children: A case study in Trinidad and Tobago. Educational Research and Review, 16(5):212-218.

Government of Zimbabwe, (1988). Social Welfare Act 10 of 1988. Government Gazette. Chapter 17:06, 10 June. Harare: Government Printers.

Government of Zimbabwe, (1996). Children’s Protection and Adoption Act 23 of 1996. Government Gazzette. Chapter 5:06. Harare: Government Printers.

Gunhidzirai, C., & Tanga, P.T. (2020). Implementation of Government Social Protection Programmes in mitigating the challenges faced by street children in Zimbabwe. Gender and Behaviour, 18(3): 16269-16280.

Hassen, I., & Manus, M.R. (2018). Socio-economic conditions of street children: The case of Shashemene Town, Oromia National Regional State, Ethiopia. International Journal of Sociology and Anthropology, 10(8): 72-88.

Hillis, S.D., Mercy, J., & Saul, J. (2016). The enduring violence against children. Psychology Health and Medicine, 137(4):1-13.

John, D. F., Yusha’u, A. A., Philip, T. F., & Taru, M. Y. (2019). Street Children: Implication on Mental Health and the Future of West Africa. Psychology, 10 (5): 667-681.

Laplanche, J., & Pontalis, J. B. (1973). The language of psychoanalysis. (1st ed). London: Routledge.

Le, M. T. H., Holton, S., Romero, L., & Fisher, J. (2018). Poly-victimization among children and adolescents in low- and lower-middle-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Trauma, Violence and Abuse, 19(3): 323–342.

Manungo, R.D. (2018). The reintegration of homeless street children through football in Harare, Zimbabwe. Unpublished PhD dissertation. Durban: University of Technology.

Meinck, F., Cluver, L., Loenig-Voysey, H., Brea, R., Doubt, J., Casale, M., & Sherr, L. (2017). Disclosure of Physical, Emotional and Sexual Child Abuse, Help seeking and Access to Abuse Response Services in Three South African Provinces. Psychology, Health and Medicine, 22(1): 94–106.

Mhlanga, R. (2021). Determinants of Recidivism in Street Children - Findings from Thuthuka Rehabilitation Centre Bulawayo Zimbabwe. Psychology & Psychological Research International Journal, 6 (3):1-5.

Mwanyekondo, A. (2020). The life experiences of street children in Harare’s Central Business District, Zimbabwe. Unpublished Masters dissertation. Harare: University of Zimbabwe.

Nathan, M.A., & Fratkin, E. (2018). The Lives of Street Women and Children in Hawassa, Ethiopia. African Studies Review, 61(1): 158-184.

Ndlovu, E., & Tigere, R. (2022). Life in the Streets, Children Speak Out: A Case of Harare Metropolitan, Zimbabwe. African Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities Research, 5(1): 25-45.

Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, (1989). Convention on the Rights of Child, Retrieved September 2023: https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/convention-rights-child.

Ogan, E.P., & Ogan E.P. (2021). Dynamics of street children in Africa. Retrieved August 2023, from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/348539465_DYNAMICS_OF_STREET_CHI LDREN_IN_AFRICA.

Palermo, T., Pereira, A., Neijhoft, N., Bello, G., Buluma, R., Diem, P., Aznar-Daban, R., Fatoumata –Kaloga, I., Islam, A., Kheam T., Lund-Henriksen, B., Maksud, N., Maternowska, M., Potts, A., Rottanak, C., Samnang, C., Shawa, M., Yoshikawa, M., & Peterman, A. (2019). Risk factors for childhood violence and poly-victimization: A cross-country analysis from three regions. Child Abuse and Neglect, 88 (7): 348–361.

Panhurst, A.N. (2019). Violence affecting children and youth in Ethiopia: Insights from a qualitative study. Retrieved October 2023: https://www.unicef.org/ethiopia/media/1856/file/Violence%20affecting%20children%20and%20youth%20in%20Ethiopia:%20Insights%20from%20a%20qualitative%20study.pdf.

Pankhurst, A.N., Negussie, N., & Mulugeta, E. (2016). Understanding Children’s Experiences of Violence in Ethiopia: Evidence from Young Lives. Innocenti Working Paper WP-2016-25, UNICEF Office of Research: Florence.

Rathore, B.S., Joshi, U., & Pareek, A. (2017). Substance Abuse among Children: A Rising Problem in India. International Journal of Indian Psychology, 5(1):176-189.

Savarkar, T., & Das, S. (2019). Mental Health Problems among Street Children: The Case of India. Current Journal of Social Sciences, 2 (1): 39-46.

Tyler, K.A., & Schmitz, R.M. (2018). Child abuse, mental health and sleeping arrangements among homeless youth: links to physical and sexual street victimization. Child and Youth Service Review, 95 (8): 327– 333.

United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), (2021). Child Labor: Global estimates 2020, trends and the road forward. Retrieved August 2023: https://data.unicef.org/resources/child-labour-2020-global-estimates-trends-and-the-road-forward/.

United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), (2020). Hidden scars: how violence harms the mental health of children. New York, UNICEF.

United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), (2006). The State of the World’s Children: Excluded and Invisible. Retrieved August 2023: https://www.unicef.org/reports/state-worlds-children-2006.

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), (2020). Working with Street Children a Training Package on Substance Use, Sexual and Reproductive Health including HIV/AIDS and STDs. Retrieved August 2023: https://www.unodc.org/pdf/youthnet/who_street_children_module1.PDF.

United Nations (UN), (2015). Transforming our world: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Retrieved September 2023: at https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/21252030%20Agenda%20for%20Sustainable%20Development%20web.pdf.

Varghese, B. (2017). Harbouring a runaway /consequences and jail time in Texas. Retrieved September 2023: https://versustexas.com/blog/harboring-runaway-child-texas/.

Yahya, M.B. (2018). Drug Abuse among street children. Journal of Clinical Research in HIV/AIDS and Prevention, 3(3),12-45.

Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency (ZimStat), (2022). Census 2022 National Report. Retrieved September 2023: https://zimstat.co.zw/#.

Author´s

Address:

Constance Gunhidzirai

Department of Social Work, Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Botswana

Private Bag UB 00705, Gaborone, Botswana

+267 355 2690

GunhidziraiC@ub.ac.bw

Author´s

Address:

Leila Patel

Centre for Social Development in Africa, Faculty of Humanities, University of

Johannesburg

P.O Box 524, Auckland Park (2006), Johannesburg, South Africa

+27 11 559 1999

lpatel@uj.ac.za