The interdependence of structural context and the Covid-19 pandemic: The case of Slovenia

Vesna Leskošek, University of Ljubljana

Abstract: The main topic of this paper is the question, what can the state management of the COVID-19 pandemic tell us about the social system in Slovenia? Slovenia was among the countries that took tough measures to limit the spread of the virus and drastically limited the contacts of staff in social services with service users, rather than adapting the measures to increased need of people for support and help to ease social distress. We examined the problem with research on the operation of social services during the first and second wave of the pandemic. The results mainly showed big differences between social services, which indicates inconsistent functioning of the social system. In some places they prohibited personal contact between employees and users of services, while in others, with the constant search for innovative ways of acting, they enabled and even encouraged contact. The main conclusion of the research is that these inconsistencies are primarily a consequence of structural deficiencies and the government's lack of awareness of the importance of these services for general well-being.

Keywords: Social services; social impact of pandemic; contacts with service users; control; digitalisation

Introduction

The Covid-19 pandemic is one of the most studied strikes of deadly diseases, affecting lives around the world and fundamentally changing the way countries operate virtually overnight. Important research interests in Covid-19 pandemic related to the social structures, as systems that seemed stable suddenly became vulnerable, and the ability of governments to react quickly to a new threat determined whether systems could withstand the pressures of a pandemic (Dominelli et al. 2020; Harrikari et al. 2021; Banks et al. 2021; Redondo-Sama et al. 2020; Ashcroft et al. 2022). The rapid spread of disease and the high number of deaths have required decisive and coordinated interventions in all subsystems of society - the economy, infrastructure, culture, health, education and social protection. Although the main measures were roughly the same all over the world, and the World Health Organisation was the main actor in providing advice on how to contain the pandemic, they also differed from country to country, creating local specificities and therefore a wide range of effects.

The main WHO (2023) guidelines were on limiting and preventing contact, on ensuring social distance, on the prevention of mass gathering and events, on hygiene measures for individuals and institutions, on protective equipment when working with people where contact cannot be prevented (especially in health and social care settings), on increasing individual responsibility for one's own life and the lives of others - i.e. increasing solidarity and awareness of the common good, and so on. WHO also provided specific guidelines for health care and long-term care institutions. In addition to the provision of protective equipment and the reorganisation of the health services, the main problem for national governments has been the provision of social distance to prevent disease transmission.

The first research reports on the operation of social workers and social services during Covid-19 pandemic in 2020 and 2021 (Dominelli et al. 2020; Harrikari et al. 2021; Banks et al. 2021) already showed that their contact with clients were regulated quite differently, depending on the extent to which the contacts were prevented or enabled. The restriction of contacts and the social distance measures have roughly created two groups, namely those who believe that people are responsible for their actions (nudge strategy) and those who took more decisive actions (decree or boost strategy) (Yan et al. 2020). The most prominent representative of the first path has been Sweden, which has based its strategy on a mutual trust that people will protect themselves and others, so that strong state action is not necessary. Most countries with the strategy of how to prevent the spread of the disease, have acted more forcefully, closing national borders, introducing home schooling, closing public institutions, restricting transport between regions and municipalities, and bringing the economy to a halt by introducing homeworking or closing down the business (Dominelli et al., 2020, Harrikari et al. 2021). These measures have required countries to take responsibility for the survival of people and businesses, which means that in addition to restrictive measures, they have also had to take measures to financially support the economy and households, and to restructure and strengthen important infrastructure such as the health and social systems.

One of the first reports on social work during the Covid-19 pandemic was published at the end of the first wave in July 2020 (Dominelli et al., 2020). It consisted of reports from sixteen countries, including Australia, Bangladesh, India, Iran, Japan, Sri Lanka, India, Iran and ten European countries. The main differences between countries were not so much in the actions taken by governments, as they followed the WHO guidelines, but in the way they were implemented and adopted according to the specific circumstances of social protection and care sector (Mooney et al., 2020). Social welfare and social work form the core structure of the service system that had crucial role in addressing needs during the pandemic to maintain the well-being of a population. There were differences between countries in how social workers were supported in their important role, if at all, with some Western countries able to reorganise and adapt quite well. Although all systems suffered to some extent, some were much less able to adapt quickly and effectively.

The main focus of this paper is on the impact of the measures taken by the Slovenian government in the field of social protection during the pandemic, as this is a central area of social work conduct and as the social impact of the measures has been shown to be at least as important as the health impact. Social isolation, loss of work or being on lay-off, closure of institutions, difficulty in accessing health and other basic services, restrictions on movement and other similar measures have caused hardships such as an increase in domestic violence and a deepening of poverty and social inequalities (Amadasun 2020; Walter-McCabe 2020; Huston & Mullan-Jensen 2011). Some groups of people have been particularly affected, such as the older people, parents with school-age children, single parents and families with disabled or older dependant members.

In Slovenia, the social impact of the pandemic was ignored for a long time, as the government focused on the health and economic impact. In taking measures, it has not paid attention to social inequalities and poverty, and to the fact that people's hardships caused by the governmental measures to curb the pandemic are generally increasing. The government also failed to adequately adapt measures to the specificities of social care and welfare sector. Shingler-Nace (2020) argues that it is crucial that key services can do their job despite the constraints and that people are able to access the services they need despite the constraints, caused by the pandemic.

The country specific measures to contain the pandemic

All measures against the spread of the pandemic that were adopted by the National Institute of Public Health (hereafter NIPH), in charge of coordinating health care measures for the entire population, also applied to social services. On March 13, 2020, the government issued special instructions for social and health-care institutions (Ministry of Labour, Family, Social Affairs and Equal Opportunities (hereafter MoLFSA) 2020):

· Visits to residential homes for older people and hospitals were prohibited (even in the case of the death of a relative);

· In other institutional premises, a strict distance was in force, personal contact between employees was not allowed, a distance of 1.5 m between two people and the use of personal protective equipment was mandatory;

· Centres for Social Work (Slovenian name for state social services, hereafter CSW) were advised to limit contacts with service users to emergency cases, and to make contacts primarily by phone or computer. Home visits were limited to emergencies.

In March 2020, the MoLFSA (2020a) issued guidelines for the protection of users, staff members and volunteers:

· Restriction of personal contacts in Centers for Social Work. Exceptions were emergency situations (child protection as defined by the Family Law, domestic violence). Social services were advised to work through digital tools (email, computer, telephone);

· Admission to Crisis Centers and contacts between parents and children under supervision (in cases of restrictions on contacts between parents and children). Crisis centers were not closed, but they had to follow the rules of NIPH. In the cases of new admissions, they had to follow the rules, which mainly related to a 14-day quarantine. Supervised contact was not advised as physical contact was restricted for people not living in the same household;

· Daycare institutions for children and adults with learning disabilities were closed, but with the exception of cases when other care cannot be provided;

· Daycare centers for different groups (elderly, people with learning difficulties, children and youth) were closed, but staff had to be available for emergency situations, so users could call or email them;

· The same was was applied for counseling and therapy services and programs;

· Residential programs remained open until the first case of corona virus infection. They had to follow the instructions of the NIPH, and for new admissions they had to follow the quarantine rules;

· Day care facilities for the homeless persons were closed. Instead, street work to provide food to the homeless was advised;

· All other social programs were closed and started working through online or telephone communication.

Wider measures that also affected the work of social workers included a ban on public transport, restrictions on mobility between cities, and restricted movement of older people. This is the context in which we conducted the research.

Methodology

In order to understand how social workers in Slovenia responded to the increased need for services in this unique situation, we conducted a survey "Social work during the Covid-19 epidemic in Slovenia". The research team consisted of researcher at the Faculty of social work, University of Ljubljana Nina Mešl, Tadeja Kodele and Vesna Leskošek, later joined by Tamara Rape Žiberna. To this paper, two research questions are asked: (1) How the governmental instructions and rules in regard to Covid-19 measures shaped the work of social workers and their contacts with service users? (2) What were the systemic supportive measures or obstacles for their work with service users?

The research was conducted in December 2021 and covered the periods of the first wave (from March 12 to the end of May 2020) and the second wave of the pandemic (from mid-October to the end of February 2021). Mixed methods of data collection consisting of interviews, diaries and an online survey were used. This paper presents the results of an online survey on the work of CSW employees during the first and second waves of the pandemic.

Since there is no list of CSW employees, a convenience sample was used. Invitations to participate in the survey were sent to 796 addresses collected from the websites of CSWs, as well as to the main institutional email addresses. The questionnaire consisted of 18 questions, 13 of which were mandatory and 5 optional; 4 questions were open. We asked the participants questions about the organization of work in both waves, about the choice between direct work with service users and remote work, about how social workers could influence these choices, how they established contacts with service users, and about the use of digital tools in these contacts. In open-ended questions, participants were asked to comment on work organization, contacts with service users, use of ICT and general satisfaction with the organization.

The survey was available online from December 7 to 21, 2020. A total of 294 people validly completed the questionnaire, of which 242 are social workers. The data were analysed using the computer program 1ka, which enables partial data processing, with the additional use of Excel and SPSS programs. Open responses were analysed using MAXQDA qualitative data analysis software. The codes for these responses consist of the letter R-respondent and the statement number from the survey summary sheet.

Results

Contacts with users of the services of Centres for Social Work

The survey showed that contacts with service users depended not only on the government's Covid-19 measures, but also on the organisation of work in individual CSW (Kodele et al. 2023). Organisational practices varied widely. Some CSWs closed their doors to both users and staff at the beginning of the declared epidemic. While these were few in number, most were closed to users and staff were not allowed to have direct contacts on the premises. A few CSWs, on the other hand, operated as usual, but with respect for measures such as distance, masks and so on. In open ended respondents one of the social workers explain:

“They [the government, the author note] should consider alternative ways of contacting service users. […] There are too many regulations on how to prevent these contacts, and not enough support to make the contacts happen. […] It should be borne in mind that the economic crisis [2009–2015, author note] changed the population that uses our services. They are not the same as in previous years, their problems are much more complex and difficult to solve. It is not possible to help them with one contact”. (R26)

The organisation of working time and the form of work were equally inconsistent. In both waves, approximately half of the respondents worked as usual, while the rest combined telecommuting with workplace work. A smaller percentage was on sick leave or took annual leave, which was partly a response to the fact that in some CSWs employees were not allowed to work from home. 14% of staff worked only from home in the first wave, rising to 23% in the second wave. The choice within flexible work organization increased satisfaction with the organization from 3.46 to 3.65 (on a 5-point scale, both standard deviations are 1.1). The reasons for greater satisfaction in the second wave were multiple. In the open-ended responses, respondents indicated the time they gained with having limited contacts with service users to cover administration, completing electronic databases, editing files and writing reports.

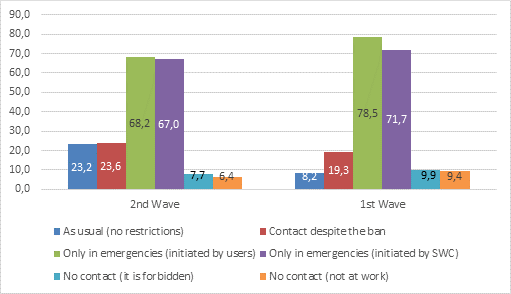

As it was pointed out, the contacts of CSW staff and service users were allowed only in emergency cases. In Figure 1 we can see that almost 20% of social workers in the first wave had contact with service users, despite the ban on contact, and this percentage increased in the second wave.

“In the first wave I have written down mainly telephone contacts. In the second wave, I consciously violated rules, but I took all precautions and had personal contacts, because these are really high-risk users. Success is priceless. It is worth violating.” (R24)

Almost 10% of respondents did not work at all in the first wave, and 6.4% in the second. Part of this percentage coincides with the prohibition of contact and the closing of CSWs, and part with the fact that children needed support with distant schooling due to the closing of schools; reasons for absence from work were also care for elderly or sick family members, or fear of infection. In majority of cases contact were limited to emergency cases.

Figure 1: Contact with service users (% of selected replies, n=233)

In open questions we have asked for the clarification of emergency situations.

“We have not been given detailed instructions on what are the emergencies in which contacts are allowed. We were left to our own creativity and each CSW unit found its own way to deal with the situation. […] The work depended on how individual social workers interpreted the instructions – some of them did nothing, because contact was forbidden, and some did everything, straining themselves to the limit.” (R100).

The differences are due to the fact that the definition of an emergency was not clear, which led to different and contradictory practices not only between CSWs, but also within a given CSW. Some CSWs defined emergencies very broadly and accepted as many service users as possible, while others allowed contacts only exceptionally. As a result, service users have had very different access to services, which has led to confusion and even conflicts.

Safety and control

Some of the CSWs responded to the conflicts that arose because people arrived uninvited due to a lack of proper information, as well as due to acute distress, by hiring security guards to prevent people from entering the CSD premises, or by only allowing those who had been arranged in advance to enter. The security guards actually decided who could enter the premises, which caused numerous complications and unpleasant situations when service users remained in front of closed doors. They came to CSW hoping to be understood, but they were not allowed to enter the premises, which increased mistrust.

“Bureaucratised to the end, closed in the CSW from the clients, like in some totalitarian institution where we are afraid of the clients, instructions on how to work were late, given in a hasty manner, […]. It was desperate, the telephone lines were burning out - that was the first wave. In the second wave, again unprepared, all the time, even the most desperate users are told by the security guard at the door that they have to make an appointment and he points to the three telephone numbers on the door. Hardly anyone gets through to the informant let alone to the PSP (first social help, author note) or to any of the other professionals. Desperation.” (R95).

The other social worker further explained:

“We could think about how to work with people, but the fact that in some cases there are no phone contact possible has barely taken into account. There are too many strict instructions on what measures to follow for safety, but people have nowhere to copy things because not everyone has a smartphone, we need more staff available on the phone to help, more staff covering calls and helping as much as possible. There is a lot of bureaucracy and people are increasingly being pushed to the edge. […] The work is well managed but there is a need for more staff to manage phone calls”. (R26)

In this respect, the situation was also very heterogeneous between the centres. Some were working as usual, but with infection prevention measures in place (masks, hand washing, disinfection, distance). One CSW reported that they had arranged a special office for interviews, where ventilation, distance and protective glass were possible, thus allowing almost uninterrupted work, although it is understandable that there were fewer service users than usual at the CSW.

“They have to announce themselves. Adequate safety distance, masks, hand hygiene. That's fine by me”. (R34)

“If the safety of all involved is ensured and the urgency of the face-to-face contact is taken into account, the contact is carried out.” (R74)

Some CSWs also worked almost as usual, taking the measures into account, which should however be seen as a search for innovative ways of working, as it was not possible to work in a completely normal way anywhere (Mešl et al. 2022). These diverse practices show that it was possible to find solutions if the CSW management was willing to do so.

“Some people were certainly constrained by the limitations to make the personal contact that means so much to them. Nevertheless, at our CSW, we have made a real effort to reach out to our users. We filled in applications and sent them to them to sign, we guided them through the procedures. I taught someone how to send me a photo of the message by sms... Also, we were never banned from all contacts, and we were actually able to meet people, even if it was not life-threatening, for which I can thank our manager (assistant director)”. (R127)

“We receive users, but not as usual. We have adapted the way we receive users, who do not enter the main building, but are admitted to a specially equipped room with an ventilation or a large enough hall. These rooms are reserved by the members of staff in a shared dokument, so we all can use it”. (R170)

Most often, those who were looking for ways of working combined several ways of working, in person, in the open air outside the CSD premises, by phone, by video call, etc.

“We made efforts together with the users, looking for possible and optimal ways of contacts and support, we were looking for solutions on an individual level - successfully!” (R140)

Another aspect of safety that caused a disengagement from service users was fear of infection. Some feared for their lives because of the constant media coverage and protective measures, and experienced fear of infection and mental distress. Others feared infecting their children or caring for disabled or elderly and dependent relatives at home.

“It is important to work with families in need, but the media and the government also have a tendency to drive users away from us for fear of infection, which is why I also have concerns about fieldwork and face-to-face contact”. (R253)

“For me, the first wave was confusion and fear, in second wave better, because I decided to work from home.” (R109)

This is also the reason why the percentage of those that worked from home in the second wave was much higher. As already mentioned, 14% of staff worked only from home in the first wave, rising to 23% in the second wave. People that were afraid of getting infected also embraced increased control and security guards.

“When it comes to your own safety and the safety of your users, it is very important to avoid as much contact as possible and thus the possibility of infection”. (R103)

These changes have had a major impact on CSW service users, as their needs have increased and changed. Our research showed that people were generally very understanding of the changes in the way CSR works, accepting a different way of working than personal contact. However, at the same time, they expected that their problems and difficulties would be addressed and solved. It was expected that the institutions would find appropriate ways of working and providing assistance, but the research showed that this happened only partially since the measures were not adapted to the purpose of the SCWs. In such a situation, many people were left without professional support, which contributed to the deepening of the problems and distress. Above all, the social distance between service users and social workers has increased.

Remote work and the use of ICT

Given that face-to-face contact was forbidden, except in cases of emergency, we were interested in the possibilities of working via information and communication technology (ICT), i.e. via telephone, video calls (Messenger, WhatsApp, Viber, Facetime, etc) and computer applications (Zoom, Teams, Skype). We would have expected the government to equip the employees at CSWs with technology if it had taken measures to cut off personal contact, as it was clear that hardship was already high without the epidemic, and that it had multiplied and intensified with it (Fiorentino et. al. 2023).

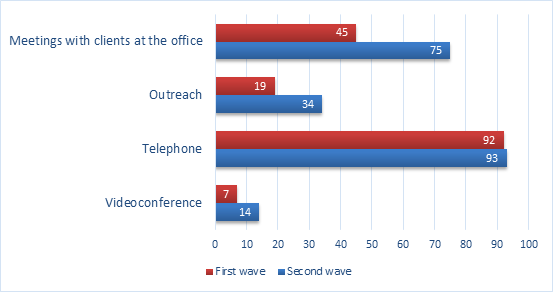

The data show that the number of direct contacts during the first wave of the pandemic decreased drastically, and that direct contacts were replaced by phone calls. The most common method of contact was by telephone, and its percentage remained the same during the first and second waves.

Figure 2. Social workers' form of contact with service users in the first and the second waves of the pandemic (n=233)

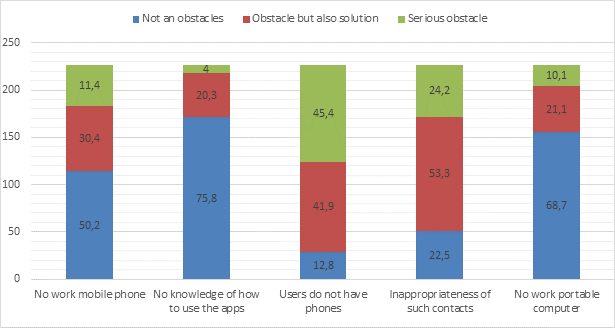

Slovenian social workers experienced many challenges in using ICT, related to the poor availability of ICT in workplaces (Figure 3). Although practically all staff have a computer, since it is necessary to regularly and thoroughly fill in the databases, the computers were mostly stationary and without cameras. Although the government banned direct contact with users, it did not provide software for remote contact (for example, Skype, Zoom or Teams) in time. One of the biggest problems arose in the case of working from home. Since desktop computers could not be transferred, there was a lack of technical support at home. The question arose of covering the costs incurred in working from home. The social workers used their own phones, since they generally do not have official smartphones, and even the Wi-Fi connection they used was private. In this regard, questions have arisen about security settings and personal data protection when working from home. Protection of personal data of service users is crucial for their trust and security. Social workers have access to sensitive personal data that, if disclosed and made publicly available, may affect not only that person but also other people in the user's personal environment. The protection of personal data is regulated by special legal acts that were apparently not respected during the pandemic.

Figure 3 Obstacles to remote work

As we can see from the Figure 3, respondents thought that remote contacts are not appropriate, because such a relationship is not personal and confidential. Establishing personal contact is the basic method of work that enables an open and respectful relationship. However, professionals have realized over time that remote contact is better than no contact at all.

Respondents in the open answers part of the survey pointed out another dilemma, which is the disclosure of personal phone numbers that they do not want to share with users, when they did not have work phones. Due to the flexibility of organizing work during the pandemic (working from home, annual leave, hybrid work), respondents redirected official calls to personal phones. Some respondents believe that it is necessary to protect privacy and separate it from work, but they have different opinions on this. Others have no reservations about it; on the contrary, even in a regular situation, they give personal phone numbers to users if the situation is difficult, and people need a lot of support.

Another issue was the necessity of teamwork and communication between staff. Weak ICT infrastructure was an obstacle to the close cooperation that was needed at a critical time during the first wave of the pandemic. But great improvements have been made over the course of the pandemic. Coordination between staff was crucial, because the forms of work were diverse and intersected with personal life, since many had children who were educated at home due to closure of schools. As the pandemic progressed, many staff members were infected or had other problems. Only a certain number of employees could be in the workplace. Since those who were at the workplace took over the work of others, they had to inform and coordinate other professionals with whom they have shared working time, because otherwise they would not be able to provide adequate support to the users. All this requires efficient ICT equipment, the possibility of video conferences, and other software. In this regard, it is not appropriate to criticize too much, since it is clear that the pandemic broke out unannounced and violently. However, it should be emphasized that it was only at that time that the lack of good equipment was recognised.

Yet another problem is the ability to establish or maintain contact with service users who do not have adequate equipment or do not know how to use it, which is especially true for elderly or poor people. There, new social inequalities emerged, which stem from the increasingly digitized public administration. Younger and better-educated generations have a much easier time mastering and handling information and communication technologies, which contributes to widening the gap between older and poorer people and other demographic groups. The general digitization of public services (for example, the introduction of e-health, e-administration, and e-psychosocial counselling, etc.) also contributes to this, which are mainly the result of the reduction of public sector costs and the introduction of market relations in these activities. The pandemic has shown that these measures rely primarily on the private resources of employees, thus shifting costs from organizations to individuals. The consequences are most visible in the reduction of the volume of services for customers.

Conclusion

On the grounds of the findings, we can state that the main problem in planning and implementing measures to limit the spread of the covid-19 virus in Slovenia was the inability to adapt the measures to the characteristics of individual sectors, which may also indicate a weak structural and institutional environment in Slovenia. Admittedly, the pandemic struck suddenly and violently, so the chaotic responses are somewhat understandable. However, individual ministries should implement measures adapted to the specific nature of their sector. In the field of social protection, the responsible Ministry should first of all enable responding and solving the growing needs of people, especially the worsening of old problems (from before the pandemic), while new problems also require quick and effective responses (for example, helping elderly people who were isolated). As the research showed, employees expected that, in addition to prohibitions related to what they must not do, they would also want to receive instructions on what they could do it, that is, how they could get in contact with people, and how they should react to the emerging needs of people (Mešl et al. 2022). Instead, they got security guards that monitored their contacts and acted repressively, which reinforced people's quite negative opinion of SWCs and social workers. This inability to adapt also shows that the pandemic was understood only in health and economic terms but not in social terms.

Examples of good practice around the word showed that the work was more successful in environments where social services were engaged in the community, which implement measures at the local level and adapted them to the characteristics of the specific environment (Dominelli et al., 2020). This practice shows that in crisis situations, mutual cooperation of all relevant services, health, education, social protection and others, which are able to adapt their work to new circumstances, is key. Banks et al. (2021) in their report stressed the importance of recognising „the critical role played by social workers in providing and supporting social and community-based care during a pandemic; acknowledge social workers as key workers; ensure provision of the necessary hygiene and protective resources; issue clear guidelines on how to maintain social work services during a pandemic, keeping services open while operating as effectively and safely as possible“ (Banks et al., 2021, p. 24).

Services must first of all recognize those groups of people who are especially exposed to the impact of the crisis in such situations, even though it affects the whole community. It is extremely important to engage civil society, which functions on the principles of solidarity and interpersonal assistance and is based on mutual trust. This has also been seen to some extent in Slovenia, but to a limited extent in those settings where inter-institutional cooperation has worked well and where social workers have continued to work in and with communities. The support was aimed at organizing mutual help between family members, social and neighbourhood support, primarily in cases where it was necessary to supply old people with food from the store or medicine, or in cases of online education of children, in which families helped each other. Those examples first of all showed that in crisis situations, quick reaction, adaptability and innovation are needed in finding answers to problems that cannot be postponed for the future.

Our research also showed that it is necessary to contextualize policies and practices in times of pandemic. Namely, the large differences between CSWs are the result of the insufficient and week organisation of public services and here the difference between good and bad management became visible. Those two dimensions are interconnected. Where the management was open to innovation and where it enabled the work to be done as well as possible, there the staff coordinated more successfully with each other and worked quite smoothly with people, always considering the safety measures to prevent infection. Elsewhere, they have closed doors and weakened ties between employees, making it less possible to find innovative solutions. Our research shows that it was not possible to get reliable and prompt information about the state of the CSWs, since no one had or collected it. These differences became apparent only later when information slowly began to enter the public.

Based on the results of the research, we can make some suggestions regarding the measures that we consider necessary for the work of social services in crisis situations, especially from the point of view of people's right to receive appropriate support according to their needs. Above all, it is important to understand that the measures taken by the states in dealing with the crisis have a direct impact on people's daily lives.

Therefore, at the macro level, it is necessary to carefully adapt the measures to the specifics of individual sectors. The sudden strike of the disease does not only cause a health crisis, , but also an economic and social crisis. Dominelli (2021) points out that in times of crisis, human rights are often violated as control over people intensifies. This is precisely what states could mitigate, if not prevent, if they managed to predict the effects of the measures they undertake. Banks et al. (2021) suggest that guidelines on how to act safely and ethically should be drawn up with frontline social workers and that it should be agreed in which cases it is acceptable to limit services. When limiting services, they should take into account the systemic factors that put certain populations at risk and the crucial role of social safety nets, including access to services.

On the level of the individual CWS research has shown that there are many opportunities to find innovative ways to connect with people. Digitization is one of those ways, but it is by no means suitable for all people (Fiorentino et al. 2023). The pandemic has shown that social workers can take on a bridging role, which mainly consists of creating support networks around individuals who need help and taking on an intermediary role between them and other institutions. They will be more successful in this if the institution provides them with professional autonomy that enables the search for innovative solutions and good mutual coordination of employees.

In general, it is easy to see that the two levels of governance, macro, meso and micro, are interlinked, interdependent and cannot be seen as separate spheres (Lombard & Viviers 2020; Kodele et al. 2023). Actions at the macro level need to be translated appropriately at the micro level, and channels for bottom-up impact need to be ensured, as only in this way is it possible to consider the heterogeneities that arise at the implementation level.

References:

Ashcroft, R., Sur, D., Greenblatt, A., & Donahue, P. (2022). The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Social Workers at the Frontline: A Survey of Canadian Social Workers. The British Journal of Social Work, 52(3), 1724–1746.

Amadasun, S. (2020). Social work and COVID-19 pandemic: an action call. International Social Work, 63(6), pp. 753–756.

Banks, S., Cai, T., Jonge, E. de, Shears, S., Shum, M., Sobočan, A. M., Strom, K., Úriz, M.J., & Weinberg, M. (2020). Practising ethically during COVID-19: social work challenges and responses. International Social Work, 63(5), 569–583.

Dominelli, L., Harrikari, T., Mooney, J., Leskošek, V., & Kennedy Tsunoda, K. (Eds.) (2020). Covid-19 and social work: a collection of country reports, Retrieved June 2021, from: https://www.iassw-aiets.org/covid-19/5369-covid-19-and-social-work-a-collection-of-country-reports/

Dominelli, L. (2021), A green social work perspective on social work during the time of COVID-19. International Journal of Social Welfare, 30(1), 7-16.

Fiorentino, V., Leskošek, V., Sarniemi, S., Romakkaniemi, M., & Harrikari, T. (2022). Development of digital social work in the early phase of COVUD-19 Pandemic in Slovenia and Finland. In T. Harrikari, J. Mooney, M. Adusumalli, P. McFadden, & T. Leppiaho (Eds.), Social work during Covid-19: Glocal perspectives and implications for the future of social work (pp. 46-62). London: Routledge.

Harrikari, T., Romakkaniemi, M., Tiitinen, L., & Ovaskainen, S. (2021). Pandemic and social work: exploring Finnish social workers’ experiences through a SWOT analysis. British Journal of Social Work, 51(5), 1644-1662.

Huston, S., & Mullan-Jensen, C. (2011). Towards depth and width in qualitative social work: Aligning interpretative phenomenological analysis with the theory of social domains. Qualitative Social Work, 11(3), 266–281.

Kodele, T., Leskošek, V., Rape Žiberna, T., & Mešl, N. (2023). Social workers’ response to Covid-19 in Slovenia: The interconnectedness of macro, mezzo, and micro levels of practice, In T. Harrikari, J. Mooney, M. Adusumalli, P. McFadden, & T. Leppiaho (Eds.), Social work during Covid-19: Glocal perspectives and implications for the future of social work (pp. 17-30). London: Routledge.

Lombard, A., & Andre V. (2020). The Micro–Macro Nexus: Rethinking the Relationship between Social Work, Social Policy and Wider Policy in a Changing World. British Journal of Social Work 50(8), 2261-2278.

Mešl, N., Leskošek, V., Rape Žiberna, N., & Kodele, T. (2022). Social work during Covid-19 in Slovenia: Absent, invisible or ignored? The British journal of social work, 53(2), 737-754.

Ministrstvo za delo, družino, socialno zadeve in enake možnosti (2020). Zaradi koronavirusa spremembe poslovanja s strankami in druga navodila, 2020. Retrieved January 2021, from https://www.gov.si/novice/2020-03-13-zaradi-koronavirusa-spremembe-poslovanja-s-strankami-in-druga-navodila/

Ministrstvo za delo, družino, socialno zadeve in enake možnosti (2020a). Navodila za ustrezno zaščito vseh uporabnikov in zaposlenih na področju socialnega varstvo. Retrieved January 2021, from https://www.deepl.com/translator#sl/en/Navodila%20za%20ustrezno%20za%C5%A1%C4%8Dito%20vseh%20uporabnikov%20in%20zaposlenih%20na%20podro%C4%8Dju%20socialnega%20varstva

Redondo-Sama, G.; Matulic, V., Munté-Pascual, A., & de Vicente, I. (2020). Social Work during the COVID-19 Crisis: Responding to Urgent Social Needs. Sustainability, 12 (20), 8595. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12208595

Shingler-Nace A. (2020). COVID-19: When Leadership Calls. Nurse Lead, 18(3):202-203.

Walter-McCabe, H. A. (2020). Coronavirus pandemic calls for an immediate social work response. Social Work in Public Health, 35(3), 69–72.

WHO (2023). Advice for the public: Coronavirus disease (COVID-19). Retrieved October 2023, from https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/advice-for-public.

Yan, B., Zhang, X., Wu, L., Zhu, H., & Chen, B. (2020). Why Do Countries Respond Differently to COVID-19? A Comparative Study of Sweden, China, France, and Japan. The American Review of Public Administration, 50(6-7), 762-769.

Author´s

Address:

Vesna Leskošek

University of Ljubljana, Faculty of social work

Topniška ulica 31, 1000 Ljubljana

Vesna.Leskosek@fsd.uni-lj.si