“The closed door?” The relationship of the Ciganos with the labour market from the perspective of the employment and training officers

Pedro Candeias, Iscte - University Institute of Lisbon & Universidade de Lisboa

Pedro Caetano, New University of Lisbon

Maria Manuela Mendes, ISCSP, University of Lisbon & Iscte - University Institute of Lisbon

Olga Magano, Open University Portugal & Iscte - University Institute of Lisbon

1 Introduction

In Portugal, Roma or Cigano[1] people face serious difficulties in integrating into the labour market. Officially, the mission of the Portuguese Employment and Vocational Training Institute is to “promote the creation and quality of employment and combat unemployment, through the implementation of active employment policies, namely vocational training.”[2] In this general context, we propose to explore the relationship between this population and this public services institution.

Throughout history, Cigano people have been marginalized from society in general and from the labour market in particular. Despite this ostracism and historical and structural racism (Bastos, 2007; Mendes, 2007) these people managed to exploit small fractions of the market, offering goods and services outside the mainstream circuit (Brazzebeni & Fotta 2015). These occupations, often occur through self-employment, or as Okley (1983) refers to the Gypsies/Roma in England, refusing to be proletarians. These activities guaranteed economic subsistence and allowed them to maintain some of their most relevant cultural traits, such as strong family proximity and independence from non-Roma (COE 1999).

Portuguese Ciganos are not recognized as a national ethnic minority, since there isn't any ethnic minority recognized by the Portuguese state. Portuguese law does not permit the production of ethnic and racial statistics There are archives of the presence of Cigano in Portugal since about the year 1500. It is a population that has been ostracized, maintaining some of its cultural practices over the years. The majority share with the rest of Roma some of the socio-structural characteristics: low levels of education, strong insertion in the labour market through informal work, and high inbreeding. However, there is some internal diversity, with some segments that can be considered middle class and elites, in other words, some Cigano perform skilled work, live outside precarious and segregated areas and some assume relevant positions in the public sphere (great merchants and businessmen, actors, researchers,etc). Nevertheless, these are very minority situations. It should also be noted that, over the generations, changes have been observed, such as greater empowerment and autonomy on the part of women, greater schooling and insertion into the labour market through the formal path (Mendes, 2007; Magano, 2010; Mendes et al., 2014). The survey conducted under the National Study on Cigano Communities (Mendes et al., 2014) on all continental Portuguese municipalities, obtain responses from about half of them and points to the existence of approximately 24,210 Ciganos. More recently, the Observatory of Cigano Communities updated these data, this time having identified 37,089 Portuguese Ciganos, around 0.4% of the Portuguese population (Calado et al., 2019). These data are based on consultations with local authorities, which tend to know only the population that is covered by social housing or social services.

According to the National Study on Cigano Communities, only 9.5% of the sample had formal employment as the main source of direct income (Mendes et al., 2014). While the contexts of professional integration vary according to geographical area, the general trend is that Ciganos perform unskilled work, of a precarious and/or seasonal nature, such as civil/public construction or agricultural works (Mendes et al., 2016). The Portuguese data accompany the general trends, according to FRA (2022) in ten European countries, including Portugal 43% of Roma were in paid work in contrast to 72% of the EU 2020 average, however, this gap is the highest in Portugal (31% vs. 75%). In addition, 56% of Roma aged 16–24 were not in employment, education or training and Roma women registered lower employment rates (28%) than Roma men (58%), discrimination experiences in employment increased between 2016 and 2021. In Portugal, 81% of the respondents felt discriminated against because of being Roma when looking for a job in the past 12 months.

The National Strategy for the Integration of Cigano Communities (ENICC, 2013, 2018) considered training and employment as one of the most priority axes of intervention. Nevertheless, some critical perspectives point out that the implemented policies tend to ignore the existence of power relations between employers and potential Cigano employees (Maeso &Araújo, 2011).

In Portugal as in other European countries, policies focusing on equal treatment of all unemployed seemed to be “inefficient” to support Roma (and other ethnic-racial minorities) because they reproduce structures of inequalities (Froy & Pyne, 2011; Messing & Bereményi, 2017), instead of being context sensitive, individually-tailored and using Cigano cultural characteristics as both a barrier and a resource (Ie & Ursin, 2022). In Portugal, the services provided at this level have a universal nature and apply to all users. The services, measures and programs of the Institute for Employment and Vocational Training (IEFP) do not take into account ethnic and racial criteria.

From our perspective, the Employment and Vocational Training Institute can assume the role of institutional mediator between Cigano people and the labour market. This is one of the most innovative aspects of this paper, whose focus is not centred on the discriminatory behaviour of employers. Considering the importance of employability for the Ciganos and the scant existing knowledge on the role played by employment centres in their integration into the labour market, we aim to explore just how this relationship is articulated, based on the standpoint of officers and directors of IEFP employment and Training Centres. More specifically, we intend to grasp the barriers that prevent Cigano users from accessing the formal labour market and to understand whether contact with Cigano users and Cigano culture interferes with these opinions. This analysis aims to fill the gap in terms of sociological knowledge on this thematic. To this purpose, we resorted to the existing literature on the relationship between Cigano/Roma people and the labour market, as well as contact theory (Allport 1954), which has been used to perceive conditions in which it is possible to reduce prejudice between groups. The empirical material consists of an online questionnaire survey applied to professionals at employment centres. This survey aimed to better understand the relationship between Cigano people and this public service. More specifically, we asked about the number of Cigano users in the employment centre, their characteristics, preferred jobs, and the most frequent jobs offered, among other questions. From this range of questions, we explored the results in two sections: contact with Cigano users and the reasons that respondents point to the failures to integrate them into the labour market. Hypothetically, we assume that professionals with greater contact with Cigano users have less stereotyped perceptions about the members of this population.

2 Literature review

The literature review reveals the complex interplay between Ciganos and the labour market and aims to depict the limitations in the access faced by Ciganos in Portugal and in other European contexts. Firstly, the low access of Ciganos to the labour market is grounded on explanations at various levels, rooted in positions of a model of ethnic segregation that analytically separates Ciganos from non-Ciganos. This means that it is based on a dynamic and relational model which emphasises the reciprocal relations between Ciganos and non-Ciganos. Secondly, it concentrates on the importance of the services provided by the employment and/or vocational training centres to foster the employability of the Ciganos. Employment policies shall not be addressed (although their crucial relevance is acknowledged), as this issue is detailed in other studies (Magano & Mendes, 2014a). This section is divided into 4 parts: individual, meso and macro levels; the relevance of employment centres and vocational training and the contact between employment centres and vocational training technicians and Cigano people.

2.1 Individual level: motivations, personal characteristics and discrimination

The viewpoints of the Ciganos concerning employment in the relational model should take into account the salient features that could configure the traditional Cigano modes of education. This is entrenched in the strength of the patriarchal system and the centrality of endogamic relationships; likewise, in family socialisation orientated towards a lifestyle anchored on the performance of activities linked to trade through self-employment, with a manifest preference for economic freedom, safeguarding a certain margin of freedom as a feature of this way of life. Over time, self-employment was a constant tendency among Portuguese Cigano, the oldest records refer to having been horse, tie or basketry selling, adapting, over time, to new market niches.

The research conducted by Casa-Nova (2007) explored the motives for the low formal employability of the Ciganos, having found, among other reasons, the existence of some resistance in the entry of the formal labour market, justified by the low wages earned, the presence of supervision, the long working hours in closed contexts, as well as the perception of discrimination perpetrated by non-Cigano employers.

From a different perspective, we point to the observable social characteristics at the individual level that some of the literature considers relevant as facilitating access to the formal labour market. The study by Magano (2010) highlighted the relations with non-Ciganos, especially arising from mixed marriages and more regular coexistence and conviviality with non-Ciganos. These diversified networks of sociability enable the “potential enlargement of their frameworks of experience and the possibility of superposition and overlapping of various types of frameworks, from those primary, to secondary and tertiary, with their rules and factors remaining outside them.” (Magano, 2010 p.180).

According to Messing (2014), it is relatively consensual at an international level that schooling and literacy are the most crucial factors for the employability of the Roma. A second transversal factor is gender. Women have an even lower presence in the formal labour market than men. Explanations for this inequality include the much stronger presence of Cigana women in family activities, both with taking care of children and in terms of their responsibility for domestic tasks. It should also be stressed that there is a stronger social control over the movements/journeys of women, and their departure from the social control of their family, neighbouring community and district of residence is subject to even tighter surveillance (Magano & Mendes, 2014b). In commercial activity, when economic sustenance is based on trade, the women working in fairs either help their husbands or other relatives do not value this activity as proper work (Mendes, 2005, 2012). Thus, when inquired, is frequent that these women don’t even mention this fact, leading them to underestimate their levels of economic activity. There are thus differences in the professions performed between men and women, men in civil construction, transport and agriculture (when in a rural context); women in domestic and industrial cleaning, and other unskilled activities in the social and educational sector. Gender inequality in access to the labour market is also reported at an international level, and for specific segments, such as that of young people (FRA, 2018). The disadvantaged position of Ciganas does not vanish with their entry into the labour market. In the study by Drydakis (2011), based on a micro dataset, a comparison was drawn between the income of women with a Roma background and women not having a Roma background in Greece. It was demonstrated that, when employed, Roma women tend to earn lower wages than their non-Roma peers, even controlling various factors, such as the type of work, schooling levels and family characteristics.

As noted above, young people are a specific segment addressed in some of the literature. The study conducted by FRA (2018) among young people aged between 16 and 24 years old, located in nine European Member States (including Portugal) demonstrated that only a minority were working (19%). Their employability tended to occur via low-skilled and heavy (hard labour) jobs, and with a limited opportunity for career progression. There was also evidence of some accumulation of disadvantages, as the young people at risk of poverty were precisely those with greater difficulties in accessing the labour market.

As a form of overcoming ethnic segregation at a work level, but also preventing discrimination by employers, we find a considerable amount of entrepreneurship and self-employment. This is an employment situation that is highly valued among Cigano peers, as it establishes a psychological and social frontier between ‘us’, belonging to their ingroup, and non-Ciganos. In the questionnaire-based survey of Roma and non-Roma entrepreneurs in Macedonia, it was concluded that many Roma entrepreneurs did not resort to state support, although they were aware that it could have been useful (Andonova et al. 2017).

2.2 Meso level: families, the labour market and the residential context

In addition to the ethnic origin of the families, which has been referred to as significant, other factors at the meso-family level are also influential. In that family referent, there could be a lack of encouragement or support to their members entering the formal labour market. This lack of incentive could also occur in relation to permanence at school, which is upstream of their entrance into the labour market (Ionescu & Cace, 2006). Up to now, we have focused on the explanations based on the position of the Ciganos. The other side of the equation emphasises the dynamics of the labour market, as there are frequent practices of negative discrimination arising from a structural closure of the labour market in relation to Ciganos. The institutionalist perspective argues that to understand the discriminatory behaviour of employers “it’s crucial to account for the context in which employers make their decisions” (Lancee, 2021, p. 1185). Sometimes, this discrimination is institutionalised, when some companies follow policies of outright rejection of job applications submitted by Roma, as evinced in the qualitative study of the ERRC in 5 Eastern European countries (Hyde, 2006). The employers’ rejection could be based on a cost-benefit analysis, in which it is considered safer to reject Roma applicants based on the negative stereotypes associated with this group (Kertesi, 2004). In Slovakia, Machlica et al., (2014) showed that, based on the sending of fictitious curricula in response to job offers, applicants with Roma surnames tended to be rejected more frequently (half the probability of being invited for an interview), when compared to people with the same qualifications but not having a Roma name.

When our analysis shifts to the meso level of the residential context, it becomes evident that this factor gains a certain relevance. In the FRA study on young people (FRA, 2018), it was concluded that residence in highly segregated zones influenced access to education, which, consequently constrained access to the labour market. Other consequences of the social networks created in the residential contexts can be a greater feeling of connection between members who share kinship, friendship or common goals. (Castro et al 2001). But further nuances are unveiled in a study carried out in Serbia (Lebedinski, 2019), in which it was found that residential segregation had a positive impact on informal employment, but a negative impact on formal employment. In Romania, Baciu et al. (2016) also identified the rural/urban distinction as being yet another additional factor limiting access to employability, with the Roma in the rural areas having fewer employment opportunities. Although the situation appears to be one of great vulnerability in rural scenarios, the case does not become more benevolent in cities. When in cities, Cigano people tend to live in what Zhou (2013) considers to be ethnic enclaves - urban neighborhoods with a high concentration of an ethnic group with similar socioeconomic characteristics, which, on the one hand, allows access to community-based institutions, however, on the other hand, it can limit contact with the outside. In the FRA study (2018) on young people, cities did not prove to be much more favourable for employability. This is explained by the higher competitiveness in city contexts. In contrast, the internal migrations flowing into large cities have left a minor stream of vacancies in medium-sized cities, where it was found that there were higher employment opportunities for young Roma (FRA, 2018).

2.3 Macro level: ciganophobia, national economy and time series

At a macro level of analysis, there are explanations based on the structure of unequal power relations. In a general European scenario, there tends to be a denial of structural racism observable on the failure to address the issue at a political and institutional level (Matos & Araújo 2016). In the specific case of Roma people, as defended by Marinaro and Sigona (2011), Roma plays a role, representing a threat in relation to non-Roma society, its identity, union and sense of security. In this way, public discourse about Roma embodies an ideal type of inner enemy (Sigona, 2011). It is possible to identify, possibly in any country with Roma people the existence of anti-Roma racism, these processes vary from country to country, and also according to the historical epoch (Powell & Baar, 2019). In Portugal, ciganophobia has a history of centuries with public measures that oscillated between expulsion, extermination and forced assimilation (Bastos 2007). Systemic and historical racism toward Cigano people is rooted in the social structures of Portuguese society (Mendes, 2007; Bastos et al. 2007; Marques 2013; Magano & Mendes, 2021). The idea of the singularity of our colonial past implies a certain illusion of easy “Lusotropicalist” coexistence and reveals the denial of racism in Portugal as an ideological and political construction (Mendes, 2007). In this perspective, several authors speak about an attempt to portray Portugal as a non-racist country (Maeso, 2019).

Second, there is a current of studies focused on the Roma economy, investigating the position of the Roma in an essentially informal market. According to this perspective, the Roma occupy various market niches, offering goods or services that are not supplied in a mainstream market. The Roma economy is endowed with some plasticity and has the capacity (or need) to adapt to the structural changes that take place in contemporary societies (Brazzabeni, Cunha, & Fotta, 2015).

The third perspective pertinent to explore is the employability of the Ciganos over time and from the standpoint of international comparisons. This concept assumes a great centrality in the labour market policies in Portugal and in other European contexts (McQuaid & Lindsay, 2005). However we do not use this concept in a restrictive, eurocentric and neutral perspective, but it is used here in a holistic perspective, as it intersects 3 components that influence a person’s employability: individual factors (a person’s ‘employability skills and attributes’); personal circumstances (it includes a range of socioeconomic contextual factors related to individuals’ social and household circumstance); and external factors (labour demand conditions and enabling support of employment-related public services) (McQuaid & Lindsay, 2005, p. 208). The study by Messing (2014) investigated 5 European countries and found that the employability of the Roma accompanied the advances in their schooling level. Also crucial is the structure of the national economies, more concretely, the supply of unskilled jobs in each country. Finally, it was understood that their employability depended on the national economic cycles, increasing in times of economic boom, and declining in situations of crisis. Hence, the elasticity of the labour market accompanies the economic cycles, also revealing the underlying structural pattern. However, it is crucial to analyse employability in a comparative perspective with the non-Roma majority. The study based on longitudinal data in Hungary showed that the employment rate of the Roma dropped sharply during the 1990s, with a growing discrepancy between the Roma and non-Roma, as the employability of the non-Roma majority rose with its increased schooling levels, which did not occur in the Roma population (Kertesi & Kézdi, 2011). It was also found that these inequalities were less heavy in the county capitals (Kertesi, 2004).

2.4 Relevance of employment centres and vocational training

Employment centres could be important in undertaking the mediation between Ciganos and the labour market. Seen from another perspective, it can simply be another social institution that perpetuates racial inequalities, along with the police force, education system, and political system, among others (Cole 2004). Some literature on the perspective of Roma, such as the institutional ethnography by Breimo and Baciu (2016) in Romania, reveals that there is a lack of trust in public employment services, given the low number of known co-ethnic people who found employment via these services. The integration in the labour market tends to occur via informal mechanisms. The same authors also refer to the existence of a lack of confidence in resorting to the employment centre services, as the Roma would be forced to expose their low literacy levels, for example, when completing lengthy forms with questions that are difficult to understand. Furthermore, the Employment Offices fail to provide genuine support to long-term unemployed Roma, and their action is limited to administrative activities such as registering the unemployed, administering clients and publishing job openings. In the meantime, genuine support of the unemployed is lacking (Messing, 2014).

In the Portuguese context, there are few studies focused on users of employment centres, with the notable exception of the work by Almeida (2017), who identified conditioning factors, both facilitating and constraining access to the vocational training measures in an Employment Centre. The second reference is the case study conducted by Pereira (2016), at one Employment and Vocational Training Centre, that sought to explore the relationship between this service and its Cigano users, and potential employers. Almeida’s study stressed the “demand” position revealed by the Cigano users, while Pereira’s highlighted the “supply” and employers’ position.

Pereira (2016) found that the users did not identify with the proposals presented to them in terms of training and employment, with there being a clear mismatch between these proposals and the users’ expectations. In addition, the job offers were practically inexistent and the training was not conducive to increased employability. Also, in the study of Bastos et al. (2007) the jobs offered to Cigano were considered by themselves excessively harsh and humiliating. On the side of the employment centre officers and employers, there was a lack of knowledge about the Cigano culture and the employment offers were not suitable to the profile of the users (Pereira, 2016). It must be borne in mind that, according to Bastos et al. (2008), part of the Cigano culture is an essentialization and results from the conditions of survival that were (and continue to be) imposed by the non Cigano majority. Consequently, it is in the interest of the dominant group to maintain these cultural traits, since it legitimizes and allows the reproduction of its dominant position (Bastos et al. 2008). Antigypsyism can be understood as an ideology that reifies the ethnic boundaries between Roma and non-Roma and is based on an assumption of internal homogeneity that is legitimized based on general notions of culture and ethnicity. These notions reject the internal diversity that can refute this anti-gypsy ideology (Mirga 2018).

While not contradicting Pereira, but seeking other effects arising from the attendance of training courses, it was considered by Almeida that there were positive impacts, as this enabled the sharing of life experiences and values, which, as a consequence, lowered the mistrust in relation to this group (Almeida, 2017). In Slovakia, the study by Bednarik et al. (2019), but also in Portugal (Pereira, 2016) showed that the majority of the unemployed Roma/Cigano participated in employment programmes, however, these programmes did not endow the users with the necessary skills to escape unemployment. Regarding these skills, it is worth bearing in mind that employability programs tend to follow a “civilizing mission” of adjusting people's personal and social traits to the needs of employers (Maeso, 2015).

2.5 Contact between employment centres and vocational training technicians and Cigano people

According to Allport's (1954) theory, contact between members from different groups helps to reduce prejudice. As long as there are fulfilled four conditions: equal status, shared goals, intergroup cooperation, and support by the authorities of laws and customs. Allport's contact theory has been corroborated but also contested. Criticisms such as that of Henriques (1984), directed at the psychology of prejudice, warn that this current does not focus (or even ignore) the socio-historical production of racism mechanisms. In an intermediate position, despite these criticisms, is the argument of Connoly (2000) who argues that the idea of a complete rejection of these hypotheses is a premature act, instead, contact must be contextualized in a historical and institutional reality of unequal power relations. The theory has also had its followers and corroborators, a meta-analysis by Pettigrew and Tropp (2006) with 515 studies showed the robustness of the theory applied to different contexts even in some situations in which the four initial conditions are not present. As this is one of the most developed trends in social psychology, this is not the place to show all the developments that can be found in other investigations (e.g., Vezzali & Starhi 2016). It is only important to mention that this theory has already been applied in a European context to explain relations between Roma and non-Roma (Giroud et al., 2021).

3 Methodology

The data discussed in this paper is based on the results of the EDUCIG project – school performance among the Ciganos: research and co-design project[3], which aims to identify and understand the school trajectories of Cigano students attending secondary education in the Lisbon and Oporto Metropolitan Areas (the biggest in Portugal, involving 18 municipalities in the first and 17 in the second), as well as their aspirations of access higher education. Specifically, one of the methodological phases consisted in the construction and application of an online questionnaire-based survey to the directors and officers working in employment and vocational training centres, aimed at learning about their experiences and perceptions in relation to the Cigano users and their relationship with the labour market, but also their level of knowledge about Cigano culture and history, as well as the experience of training courses on Cigano history and culture. The questionnaire-based survey was designed and applied through the Qualtrics platform. The use of an online questionnaire platform is a more economical solution than a paper questionnaire (Greenlaw & Brown-Welty 2009) to which we add speed in creating the database and minimizing the social disability effect that occurs in face-to-face surveys. Besides, it is a low-cost technique that allowed it to cover a vast group of professionals, who would not be available to respond face-to-face to a research team, even in a pandemic context. On the other side, it has some limitations: The closed character of the questions is considered to be of greater importance, which does not allow us to go deeper into the reasons underlying the opinions of the participants.

The link to the survey by questionnaire was sent by email to all the employment centres of the two metropolitan areas. It was requested that the questionnaire should be accomplished by directors and officers of the employment area and officers of the training area. As it is not possible to know the actual size of this universe, it is likewise not possible to gauge the response rate. The data collection took place between October 2019 and April of 2020, giving rise to a sample of 252 valid questionnaires. The empirical component of this article starts with a brief description of the participants, and subsequent exploration of two types of indicators: i) the contact with Cigano users and Cigano culture: 2) the motives that the respondent indicate for the difficulties of integration in the labour market on the part of the Cigano users. The purpose of this paper is to test the assumption, if the technicians have a greater knowledge about the Cigano history and culture, they will be able to develop a more holistic (and complex) interpretation of the relation of the Cigano and the labour market. Consequently, develops greater empathy with Cigano users and provides a different and more hospitable attendance and referral (Levinas, 2011), and more flexible and oriented strategies.

4 Results

4.1 Characterisation of the sample

The sample has a higher proportion of women (198 women, 80% and 50 men, 20%). However, we were unable to discern whether this discrepancy is due to a methodological bias (as women tend to be more drawn to answering questionnaire-based surveys (Smith, 2008), or to gender asymmetries in this particular population. In terms of age, more than half (52%) of the respondents are aged between 45 and 54 years old. The most frequent professional category is senior officer, accounting for 66% of the sample, followed by trainer and teacher, representing 13%. Concerning their position in the organisation, 7% were directors, 18% were employment officers and 36% were training officers. The majority (56%) have performed these roles for more than 20 years. Regarding their work area, 53% worked in training and 46% in job search. Geographically, the sample is more concentrated in the Lisbon Metropolitan Area (78%), which could partly be due to the higher number of employment centres located in this zone.

4.2 Contact with Cigano culture and Ciganos

The first indicator refers to contact with Cigano culture and Cigano people (Table 1). Cultural contact is understood as the possession of abstract knowledge, obtained through academic or professional training based on the theories of racism, ethnicity, history and culture of Cigano people. The questions, formulated in different positions of the questionnaire, were: Have you ever studied topics on minorities and cultural diversity?, Have you attended any training to raise awareness about the culture/history of Cigano people?, In your professional career, have you ever attended or followed Cigano people?, Are there Cigano mediators in your workplace? It is assumed that technicians who have this sort of knowledge will have a greater familiarity and proximity to issues more or less linked to the Cigano users they attend. Among the battery of four dichotomous indicators, the first two refer to contact at a more theoretical level, through the study of related topics about minorities and cultural diversity, in which the majority (60%) answered affirmatively. It should be borne in mind that, due to the way that the question was posed, while these topics might not be specific to Cigano culture, even so, they could lead to generating some sensitivity. The item covers cultural contact, although it is more precisely also related to sensitivity in dealing with differentiated ethnic groups and to know the theories about ethnicity. Secondly, and still in a theoretical context, attendance of training actions on the history and/or culture of the Cigano people is found to be present in merely ¼ of the sample. The following indicators refer to face-to-face contact, through service rendered to Cigano users, which is practically omnipresent in the respondent sample (96%). Finally, equally pertinent, but showing a rather low presence, is the existence of Cigano mediators, with only 7% of affirmative answers. The inclusion of these indicators is based on the assumption that the existence of mediators could facilitate/improve contact with Cigano users.

Table 1. Contact with Cigano culture and Ciganos, line %

|

Contact with Cigano culture and Ciganos users |

Yes |

No |

|

Studied topics about minorities and cultural diversity |

60.7 |

39.3 |

|

Attended some awareness-raising training on Cigano culture/history |

25.4 |

74.6 |

|

Provides or has provided customer service to Ciganos |

96.4 |

3.6 |

|

Existence of Cigano mediators at the workplace |

6.9 |

93.1 |

Source: EduCig (2020) survey of employment centres

To investigate the extent to which these four indicators are interrelated, Chi-square tests were run for each pair of indicators. The matrix presented in Table 2 shows that relationship is most evident between two pairs of variables: the study of topics about minorities and cultural diversity, and the training and/or awareness-raising actions on Cigano history and culture. The second correlation is seen between the attendance of training and the existence of Cigano mediators at the employment centre.

Table 2. Matrix of association for the indicators of contact with Cigano culture and Cigano users, Chi-square test value and significance of the p-value

|

|

Studied topics |

Attended training |

Provided service to Ciganos |

Cigano Mediators at the workplace |

|

Studied topics |

- |

|

|

|

|

Attended training |

17.56*** |

- |

|

|

|

Provided customer service to Ciganos |

0.98 |

1.07 |

- |

|

|

Cigano Mediators at the workplace |

3.65 |

19.12*** |

0.70 |

- |

***p<0.001

Source: EduCig (2020) survey of employment centres

Two new composite variables were created, the first, named cultural contact is the sum of the first two items: having studied about ethnic minorities and having received training about Cigano culture. The following two items were used to create the second indicator, personal contact with Ciganos. Hence, these two new indicators vary between 0 (no contact) and 2 (contact in the two items). Although some relationship is expected between the two new indicators, it would make sense to explore them as distinct variables as they correspond to relatively different forms of contact.

4.3 Motives for failure of integration in the labour market

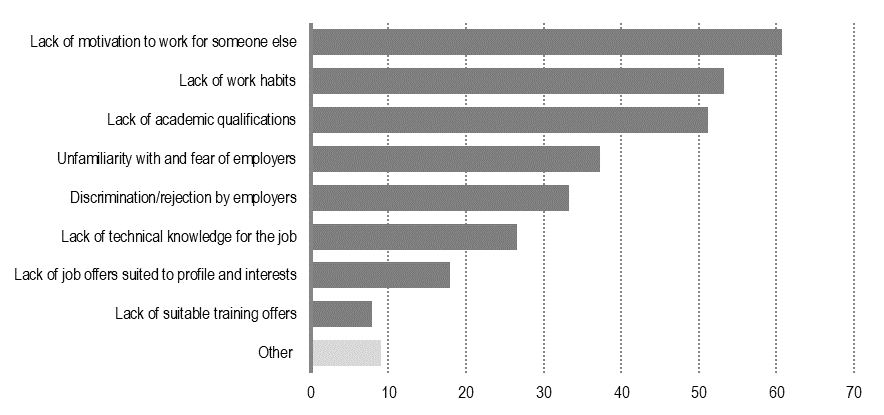

A series of nine options were used to search for the motives that the respondents attribute to the failure of Ciganos integration in the labour market. The question asked was: What are the main reasons for the failure to insert Cigano people into the labour market? The answer options were multiple choice The majority pointed to individual traits: lack of motivation to work as an employee for someone else, of work habits and of academic qualifications. Ranked in the fourth and fifth positions are reasons associated with the employers, such as unfamiliarity, fear, and negative discrimination. Structural characteristics related to the functioning of labour market or employment centres are the least frequently indicated.

Figure 1. Reasons for failure of integration in the labour market, %

Source: EduCig (2020) survey of employment centres

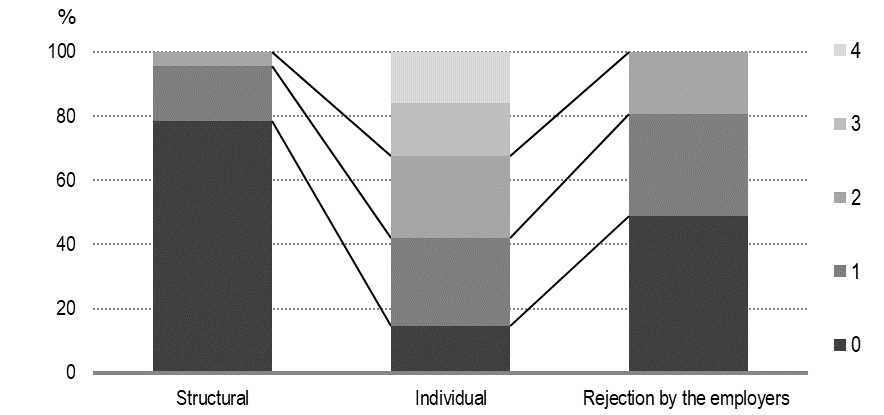

In the second step, an attempt was made to aggregate the eight items described above into latent variables. Factor Analysis using the Maximum Likelihood method aggregates three components (Table 3). This model can be complemented by a Chi-Square goodness-of-fit test, which is not statistically significant, meaning that there is no systematic variance after these 3 factors have been extracted. Consequently, this leads to the conclusion that the model is appropriate[4].

The first factor aggregates two structural motives of the labour market and of training: the lack of supply, both in terms of employment and training offers. The second component aggregates the explanations focused on the characteristics of the Cigano users: lack of knowledge and qualifications and, associated with personality traits, lack of motivation and work habits[5]. In the third place, the explanations associated with the employers, whether due to unfamiliarity, fear or discrimination.

Table 3. Factor loadings of the motives for failure of integration in the labour market

|

|

Structural |

Individual characteristics |

Rejection by employers |

|

Lack of job offers suited to profile and interests |

0.999 |

-0.001 |

0.000 |

|

Lack of suitable job offers |

0.285 |

0.165 |

-0.009 |

|

Lack of technical knowledge for the job |

0.236 |

0.678 |

-0.146 |

|

Lack of academic qualifications |

0.207 |

0.668 |

0.009 |

|

Lack of motivation to work for someone else |

-0.007 |

0.339 |

-0.268 |

|

Lack of work habits |

-0.061 |

0.312 |

-0.183 |

|

Unfamiliarity with and fear of the employers |

0.112 |

0.304 |

0.418 |

|

Discrimination/rejection by the employers |

0.242 |

0.337 |

0.404 |

Source: EduCig (2020) survey of employment centres

The items comprising each component were aggregated into three new variables based on the sum of which each variable had higher factor loading. For example: Structural component was the sum of the responses “Lack of job offers suited to profile and interests” and “Lack of suitable job offers”. Each original variable count as one (1) value. The descriptive measures for each of the new items are analysed below and their visual representation is presented in Figure 2. The number of structural motives and motivations centred on the employers varies between zero and two motives mentioned. The motivation of individual order can reach up to four values, corresponding to the enumeration of the four motives. The zero bars, the darkest in colour, near the axis, indicate the weight of the respondents that did not refer to any of these factors. The first deduction that can be made from Figure 2 is the tendency towards the absence of mentioning the structural factors: 78% do not refer to any explanation framed in this component. Rejection by employers also tends to be one of the factors least referred to (49% did not refer to any of them). In the individual motivations, the respondents most frequently pointed to one (27%) or two (25%) of the four motives comprising that component. Only 14% did not indicate motives from this component.

Figure 2. Number of motives indicated per component, %

Source: EduCig (2020) survey of the employment centres

The last step entails understanding how the cultural and personal contact with Cigano users is related to the different types of explanations that are indicated for the failure of integration in the labour market. To achieve this aim, tests were run on the ordinal correlation between the two contact indicators and the three types of explanations.

The data presented in Table 4 enables understanding firstly, the difficulty of integration in the labour market due to rejection of the employers is independent of the personal and cultural contact. Secondly the structural characteristics of the labour market only reveal a positive relationship with cultural contact through knowledge of Cigano history and culture. Lastly, individual characteristics are present in the group that shows cultural contact but are more intense in the group with greater personal contact.

Table 4. Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients for cultural and personal contact and motives indicated for the employability of Cigano users

|

|

Structural |

Individual characteristics |

Rejection by employers |

|

Cultural contact |

0.127* |

0.135* |

0.033 |

|

Personal contact |

-0.017 |

0.200** |

-0.051 |

*p<0.05, **p<0,01

Source: EduCig (2020) survey of employment centres

Furthermore, two types of factors were also tested. The first tests the role performed by the study participants (director, employment search officer and training officer), both with the two types of contact and with the motives indicated for the low employability of the Cigano users. The Kruskal-Wallis distribution comparison tests did not prove to be statistically significant.

In the second test, the aim was to understand whether the type of contact and the explanations indicated for the relationship of the Ciganos with the labour market were related to opinions concerning policies of incentives for employers to recruit Cigano job-seekers. The question was: “Do you consider that there should be incentives for employers to hire workers of Cigano origin?” With the answer options of yes/no. Although the majority disagrees, this question divides the sample (47% yes, 53% no). It was found that the participants who most refer to motives of structural order and focused on the employers are the ones who most agree with this measure. This could be interpreted within a more comprehensive set of positive attitudes towards the Cigano users.

5 Discussion

There appears to exist, among the directors and employment search and training officers, a weak belief in explanations that justify the low employability of the Cigano users due to rejection by the employers, although some literature suggests this effect (Machlica et al., 2014). Motives of structural order, associated with the existing offer in the labour market and training, are more frequently stated by professionals who received training or studied topics about ethnic minorities. This finding suggests that this type of training could give rise to more in-depth knowledge, to a better understanding of the characteristics of the target group and its needs. It is known that certain ethnic groups cluster around certain activities, are considered occupational segregation (Catney and Sabater, 2015). These niches, due to their specificity and low representativeness, may not be included in the offers that exist in employment centers. With the growing importance of technology in the labour market, some professions become obsolete, placing members of less qualified ethnic groups in an even more vulnerable position, or forcing them to reinvent themselves and discover new niches. We were able to perceive that, more than a distrust Breimo and Baciu (2016) (or associated with this distrust) there is a lack of knowledge. We also noticed that the mismatch identified by Pereira (2016) may not just be the result of a strategy or ignorance of employment technicians, but of structural factors in the labour market (reduced supply of employment suited to their needs, negative discrimination against employers).

In turn, motivations of individual order are related to cultural contact, but even more so to personal contact. Although according to the contact theory (Allport, 1954) technicians with more contact with Cigano people would be expected to have less prejudice, as happened to the general population (Giroud et al., 2021). It is to be taken into account that the four conditions that Allport considered necessary for lessening prejudice, and therefore for reducing negative perceptions in relation to the exogenous group, are simply not met: equal status, shared goals, intergroup cooperation, support by the authorities of laws and customs. The opposite was found; greater contact was associated with negative attitudes (conflict or negative contact). It should also be highlighted that greater personal contact shows no relationship with the other types of explanations.

The second point to be developed in our discussion answers the question: shouldn’t greater knowledge of the Cigano users, at a theoretical and abstract level, lead to a reduction of negative perceptions? In all truth, although there is a correlation between cultural contact with Cigano culture and the justifications of individual order for this group’s failure to incorporate in the labour market, this could be due to the high co-occurrence between this item and the item relative to personal contact. The correlation value between the explanations of individual order and the personal contact indicator is 0.200, but if the values of the individual explanations were correlated with a cultural contact and personal contact indicator (the sum of the four items shown in Table 1), the value of the correlation coefficient decreases to 0.177. This would lead us to believe that cultural contact helps to reduce the weight of the explanations of individual order, thus enabling the officers to have a more comprehensive and multidimensional perspective about the complex relationship between the labour market and the Cigano population.

6 Conclusion

This paper sought to understand the opinions held by the directors and officers of the employment centres in relation to the Cigano users, more specifically, the motives that these civil servants indicate to explain their difficulty in employability.

As this is a complex relationship it would be preferable to sidestep monocausal explanations and move towards a more comprehensive model that considers the different parts of the equation. Based on the data, we were able to classify three types of plausible explanations for the failure of Cigano users to integrate into the labour market. We propose three types of reasons: structural explanations, individual explanations and the explanations anchored on the resistance revealed by the employers. Based on ordinal correlation measurements we were able to understand that there is a correlation between the personal contact indicator and individual characteristics. There is also a relationship between the cultural contact indicator and the explanations of structural order and individual order, although the intensity of the correlations is lower than in the case of the personal contact indicator. This would lead us to believe that cultural contact, via training and the study of topics associated with ethnic minorities reduces the importance attributed to individual characteristics, and enables a more encompassing perspective, which also considers the contextual factors of the labour market. It should be stressed that the respondents who pointed more frequently to motives of structural order and focused on the employers also tend to agree with incentive measures for employers aimed at recruiting Cigano job seekers, which could be framed in a much larger set of positive attitudes and desire of change in the way that the labour market deals with Cigano users.Bear in mind that the effect may not be causal, but rather circular, since the participants who consider the importance of the contextual factors in the difficulties of employability of Cigano users could be people who seek out training in order to be able to understand the complex phenomenon of the employability of ethnic minorities.

The question could be even more convoluted in that the directors and officers, by emphasising explanations of individual nature rather than structural, could, unconsciously, also be valorising their belief in their own participation in this process, a relational process. If they were to point only to structural issues, they could be allowing themselves to sink into fatalism and a disbelief in their participation in the process. Therefore, this suggests that it would be important to minister training to these professionals that reinforces their active role in the success of the employability of the Cigano users, both through the assessment of their needs and potentialities, and in their referral towards the solutions most suited to their profile.

Two recommendations for social policy emerge based on these findings: firstly, it seems to make sense to carry out training on ethnic minorities and on Cigano history and culture among the employment and training officers. It is plausible that this could help the officers in their customer service work with Cigano users (which is fairly frequent). Training of this nature should also be ministered among employers, in order to demystify stereotypes in relation to Ciganos, turning them into potential workers to be hired. In methodological terms and as a pointer for the development of research in this area, it would be useful if the attitudes and perceptions that these officers express about the employability of Cigano users were assessed before and after this training, so as to unravel the control effect in action. Secondly, the Cigano people could be encouraged to use the employment and training services through awareness-raising actions on their rights in this matter and concerning these state services. Intervening among both parties could contribute to reducing what Breimo and Baciu (2016) refer to as mutual mistrust.

The employment centres could be a gateway for entering the labour market, regardless of the ethnic belonging of the users. A more comprehensive understanding of the failure of integration in the labour market of Cigano users, which involves not emphasising factors and explanations of individual and essentialist order could help the employment and training public service and their officers to achieve their mission, and build a fairer society, reducing the levels of structural inequality that still and overwhelmingly affect the Cigano population. But there is also a pressing need to enforce an expansion of training offers (frequently maladjusted to the users’ school qualifications) and referral to job offers (with awareness-raising among employers).

Therefore, by emphasizing the role of actors working in employment and training services, the aim was to highlight the importance of their key role in mediating between Ciganos users and employers, which could contribute to shortening the social and cultural distance between Ciganos and the labour market.

Institutional Review Board Statement: The data collection instruments were approved by the Ethics Committee of the ISCTE – Instituto Universitário de Lisboa.

References:

Allport, G. (1954). The Nature of Prejudice. Reading: Addison-Wesley Publishing.

Almeida, S. (2017). A Vida para Além das Feiras. A importância das medidas de formação profissional na trajetória profissional do Povo Cigano. (Master Thesis in Social Work), Faculdade de Psicologia e Ciências da Educação da Universidade de Coimbra, Coimbra.

Andonova, V. G., Nikolov, M., Selmani, D., Mitevski, I., & Osmanovska Kundovska, F. (2017). The policies and measures for self-employment and entrepreneurship in Macedonia among the Roma community. Review of Economic Studies and Research Virgil Madgearu, 10(2), 5-26. doi: 10.24193/RVM.2017.10.07.

Araújo, M. (2016). A very ‘prudent integration’: white flight, school segregation and the depoliticization of (anti-)racism, Race Ethnicity and Education, 19(2), 300-323, DOI: 10.1080/13613324.2014.969225

Araújo, M. (2019). À procura do “sujeito racista”: a segregação da população cigana como caso paradigmático. In: Cadernos do Lepaarq, v. XVI, n.31., p. 147-162,

Baciu, L. E., Dinca, M., Lazar, T., & Sandvin, J. T. (2016). Exploring the social relations of Roma employability: The case of rural segregated communities in Romania. Journal of Comparative Social Work, 11(1), 1-30. doi: https://doi.org/10.31265/jcsw.v11i1.138

Bastos, J.G.P. (2007). Que futuro tem Portugal para os portugueses ciganos, Working Paper CEMME - Centro de Estudos de Migrações e Minorias Étnicas (5)

Bastos, J.G.P., Correira, A. & Rodrigues, E. (2007). Sintrenses Ciganos. Uma abordagem estrutural-dinâmica, Lisbon: Câmara Municipal de Sintra/ACIDI

Bastos, J.G.P., Correira, A. & Rodrigues, E. (2008). O Que Podem Esperar de Portugal os Portugueses Ciganos? paper presented at CEMME / FCSH.

Brazzabeni, M., Cunha, M. I., & Fotta, M. (2015). Introduction: Gypsy economy. In M. Brazzabeni, M. I. Cunha & M. Fotta (Eds.), Gypsy Economy – Romani Livelihoods and Notions of Worth in the 21st Century. New York & Oxford: Berghahn Books.

Breimo, J. P., & Baciu, L. E. (2016). Romanian Roma: An Institutional Ethnography of Labour Market Exclusion. Social Inclusion, 4(1), 116-126. doi: 10.17645/si.v4i1.539

Castro A., Duarte, I., Afonso, J., Sousa, M., Lobo Antunes, M.J., & Salgueiro, M. (2001). Os Ciganos Vistos pelos Outros. Coexistência Inter-Étnica em Espaços Urbanos. Cidades - Comunidades e Territórios, (2), 73-84.

Casa-Nova, M. J. (2007). Gypsies, ethnicity, and labour market: An introduction. Romani Studies, 17(1), 103-123.

Gemma C. & Albert S. (2015). Ethnic Minority Disadvantage In The Labour Market Participation, Skills And Geographical Inequalities, York, Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

Cole, M. (2004). ‘Brutal and stinking’ and ‘difficult to handle’: the historical and contemporary manifestations of racialisation, institutional racism, and schooling in Britain, Race Ethnicity and Education, 7(1), 35-56.

Connolly, P. (2000) What Now for the Contact Hypothesis? Towards a New Research Agenda, Race Ethnicity and Education, 3(2), 169-193, DOI: 10.1080/13613320050074023

COE. (1999) Economic and employment problems faced by Roma/Gypses in Europe Committee of Experts on Roma and Travellers, MG-S-ROM (99) 5 rev, Council of Europe https://rm.coe.int/0900001680928544

Drydakis, N. (2011). Roma Women in Athenian Firms: Do They Face Wage Bias? Ethnic and Racial Studies, 35(12), 2054-2074. doi: 10.1080/01419870.2011.634981

FRA. (2018). Transition from education to employment of young Roma in nine EU Member States. Luxembourg: European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights.

FRA (2022). Roma in 10 European countries. Main results, https://fra.europa.eu/en/publication/2022/roma-survey-findings#publication-tab-1.

Fejzula, S. (2019). The Anti-Roma Europe: Modern ways of disciplining the Roma body in urban spaces, Direito & Praxis, 10(3), 2097-2116. doi: 10.1590/2179-8966/2019/43882

Froy, F. & Pyne, L. (2011). Ensuring Labour Market Success for Ethnic Minority and Immigrant Youth. OECD Local Economic and Employment Development (LEED) Working Papers. doi: 10.1787/5kg8g2l0547b-en

Giroud, A., Visintin, E.P., Green, E.G.T. & Durrheim, K. (2021). ‘I don't feel insulted’: Constructions of prejudice and identity performance among Roma in Bulgaria. J Community Appl Soc Psychol.; 31: 396–409. https://doi.org/10.1002/casp.2524

Greenlaw, Corey & Brown-Welty, Sharon. (2009). A Comparison of Web-Based and Paper-Based Survey Methods Testing Assumptions of Survey Mode and Response Cost. Evaluation review. 33 (5). 464-480. 10.1177/0193841X09340214.

Henriques, J. (1984). "Social psychology and the politics of racism", in Henriques, J., Hollway, W, Urwin, C. Venn, C &Walkerdine V., Changing the Subject. Psychology, Social Regulation and Subjectivity. London: Routledge (58-87).

Hyde, A. (2006). Systemic Exclusion of Roma from Employment. ERRC. doi: http://www.errc.org/roma-rights-journal/systemic-exclusion-of-roma-from-employment

Ie, J., & Ursin, M. (2022). The Twisting Path to Adulthood: Roma/Cigano Youth in Urban Portugal. Social Inclusion, 10(4), 93-104. doi: https://doi.org/10.17645/si.v10i4.5683

Ionescu, M., & Cace, S. (2006). Employment Policies for Roma. Bucharest: The expert Publishing House.

Kertesi, G. (2004). The Employment of the Roma – Evidence from Hungary. Budapest Working Papers on the Labour Market, 1, 1-50.

Kertesi, G., & Kézdi, G. (2011). Roma employment in Hungary after the post-communist transition. Economics of Transition, 19(3), 563–610. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0351.2011.00410.x

Kóczé A.& Rövid, M. (2017). Roma and the politics of double discourse in contemporary Europe, Identities, 24(6), 684-700, doi: 10.1080/1070289X.2017.1380338

Lancee, B. (2021). Ethnic discrimination in hiring: comparing groups across contexts. Results from a cross-national field experiment, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 47:6, 1181-1200, DOI: 10.1080/1369183X.2019.1622744

Lebedinski, L. (2019). The Effect of Residential Segregation on Formal and Informal Employment of Roma in Serbia. Eastern European Economics. doi: doi.org/10.1080/00128775.2019.1689143

Levinas, E. (2011). Entre Reconhecimento e Hospitalidade. O saber da filosofia.Lisbon, Edições 70.

Machlica, G., Žúdel, B., & Hidas, S. (2014). Bez práce nie sú koláče. Komentár k analýze Unemployment in Slovakia. IFP Policy paper (30), 1-6.

Maeso, S.R. (2015). ‘Civilising’ the Roma? The depoliticisation of (anti-)racism within the politics of integration, Identities: Global Studies in Culture and Power, 22(1), 53-70, DOI: 10.1080/1070289X.2014.931234

Maeso, S.R. & Araújo, M. (2011). ‘Civilising’ the Roma/Gypsies. Public policies,‘employability’ and the depoliticisation of (anti-)racism in Portugal, TOLERANCE Project Working Papers (38)

Maeso, S.R. (2019). O Estado de negação e o presente-futuro do antirracismo: Discursos oficiais sobre racismo, ‘multirracialidade’ e pobreza em Portugal (1985-2016), Direito e Praxis 10(3), 2033-2067. doi: 10.1590/2179-8966/2019/43883|

Magano, O. (2010). “Tracejar vidas normais” Estudo qualitativo sobre a integração social de indivíduos de origem cigana na sociedade portuguesa. (Ph.D. Thesis in Sociology), Universidade Aberta.

Magano, O. & Mendes M.M. (2014a). Ciganos e políticas sociais em Portugal. Sociologia, Revista da Faculdade de Letras da Universidade do Porto, Número temático, 15-35.

Magano, O. & Mendes M.M. (2014b). Mulheres ciganas na sociedade portuguesa: tracejando percursos de vida singulares e plurais. REVISTA SURES, Revista Digital do Instituto Latino-Americano de Arte, Cultura e História- Universidade Federal da Integração Latino-Americana-UNILA : Diversidade, plurilinguismo e interculturalidade(3), 1-15.

Magano, O. & Mendes, M.M. (2021). Key Factors to Education Continuity and Success of Ciganos in Portugal, in Mendes M.M., Magano, O. & Toma, S. Social and Economic Vulnerability of Roma People, Key Factors for the Success and Continuity of Schooling Levels, Cham: Springer (135-151) doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-52588-0

Marinaro, I.C. & Sigona, N. (2011) Introduction. Anti-Gypsyism and the politics of exclusion: Roma and Sinti in contemporary Italy, Journal of Modern Italian Studies, 16(5), 583–589, DOI: 10.1080/1354571X.2011.622467

Marques, J.F. (2013). O racismo contra as coletividades ciganas em Portugal: sequelas de uma modernização, in Mendes, M.M. & Magano, O. Ciganos Portugueses Olhares Plurais e Novos Desafios numa Sociedade em Transição, Lisbon: Mundos Sociais (111-122)

Matos, C. & Araújo, M. (2016). Tempos e contratempos do (antir)racismo no Brasil e em Portugal: Uma introdução, Revista de Ciências Sociais, 44, 13–25.

McQuaid, R.W. & Lindsay, C. (2005). The Concept of Employability. Urban Studies, 42(2), 197– 219, DOI: 10.1080/004209804200031610

Mendes, M.M. (2005). Nós, os Ciganos e os Outros, Etnicidade e Exclusão Social. Lisbon: Livros Horizonte.

Mendes, M.M. (2007). Representações Face à Discriminação. Ciganos e ImigrantesRussos e Ucranianos na Área Metropolitana de Lisboa (Ph.D. thesis in Sociology), Instituto de Ciências Sociais, Lisbon, Portugal

Mendes, M.M. (2012). Identidades, Racismo e Discriminação: Ciganos da Área Metropolitana de Lisboa. Lisbon: Caleidoscópio.

Mendes, M.M. Magano, O. & Candeias, P. (2014). Estudo Nacional Sobre as Comunidades Ciganas. Lisbon: ACM.

Mendes M.M. Magano, O. & Candeias, P. (2016). Social and Spatial Continuities and Differentiations Among Portuguese Ciganos: Regional Profiles. Studia UBB Sociologia, 61(1), 5-36. doi: 10.1515/subbs-2016-0001

Messing, V. (2014). Patterns of Roma Employment in Europe. NEUJOBS Policy Brief (D19.4).

Messing V. & Bereményi Á.B. (2017). Is ethnicity a meaningful category of employment policies for Roma? A comparative case study of Hungary and Spain, Ethnic and Racial Studies, 40(10), 1623-1642, doi: 10.1080/01419870.2016.1213402 p. 1625

Mirga-Kruszelnicka, A. (2018) Challenging Anti-gypsyism in Academia: The Role of Romani Scholars, Critical Romani Studies 1(1) 8-28, doi: 10.29098/crs.v1i1.5

Okley, J. (1983) The Traveller-Gypsies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Pereira, I. (2016). “Ninguém dá trabalho aos ciganos!” Estudo qualitativo sobre a (des)integração dos ciganos no mercado formal de emprego. (Master thesis in Intercultural Relations), Universidade Aberta.

Pettigrew, T.F. & Tropp, L.R. (2006). A Meta-Analytic Test of Intergroup Contact Theory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 90(5) 751-783, doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.90.5.751

Powell, R. & van Baar, H. (2019). The Invisibilization of Anti-Roma Racisms. In: H. van Baar, A. Ivasiuc, and R. Kreide (eds) The Securitization of the Roma in Europe. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 91-113.

Sigona, N. (2011). The governance of Romani people in Italy: discourse, policy and practice, Journal of Modern Italian Studies, 16(5), 590-606, DOI:10.1080/1354571X.2011.622468

Smith, W. G. (2008). Does Gender Influence Online Survey Participation?: A Record-linkage Analysis of University Faculty Online Survey Response Behavior. ERIC Document Reproduction Service.

Strangleman, T., & Warren, T. (2008). Work and Society. Sociological approaches, themes and methods. London/New York: Routledge.

Vezzali, L. & Stathi S. (2016) Intergroup Contact Theory. Recent developments and future directions, Taylor and Francis

Zhou, M. (2013) Ethnic enclaves and niches. The Encyclopedia of Global Human Migration, I. Ness (Ed.). https://doi.org/10.1002/9781444351071.wbeghm201

Author´s

Address:

Pedro Candeias, PhD

ISCTE-IUL and ISAMB-ULisboa

ISCTE-IUL. Av.ª das Forças Armadas 1649-026 Lisboa. Portugal

pedro_candeias@iscte-iul.pt

https://ciencia.iscte-iul.pt/authors/pedro-candeias/cv

Author´s

Address:

Pedro Caetano

Universidade Nova de Lisboa, Centro Interdisciplinar de

Ciências Sociais – Lisboa – Portugal.

Avenida de Berna, 26-C, 1069-061 Lisboa

caepedro@gmail.com

Author´s Address:

Maria Manuela Mendes

ISCSP-UL and Iscte - Instituto

Universitário de Lisboa, Centro de Investigação e Estudos de Sociologia (Cies_Iscte) −Lisboa − Portugal.

Avenida das Forças Armadas, 1600-083 Lisboa

mamendesstergmail.com

Author´s Address:

Olga Magano

Universidade Aberta and Iscte - Instituto Universitário de Lisboa, Centro de

Investigação e Estudos de Sociologia (Cies_Iscte) −Lisboa −

Portugal.

Avenida das Forças Armadas, 1600-083 Lisboa

olga.magano@uab.pt