Post-Critical Social Work?

Tom Grimwood, University of Cumbria

Post-Critical Social Work?

In a now often-quoted passage of his book One Way Street, Walter Benjamin writes:

Criticism is a matter of correct distancing. It was at home in a world where perspectives and prospects counted and where it was still possible to adopt a standpoint. Now things press too urgently on human society. (1928 [1996], 476)

Benjamin wrote this in 1928; however, such a quote may seem even timelier in the current age. After all, today the social world is marked by deep-rooted complexities, tensions and challenges which disturb the notion of ‘correct distancing.’ In Tina Wilson’s words there is a ‘shift from linear human causality and progressive problem solving to constitutive complexity and an unpredictable relation with more-than-human worlds.’ (Wilson 2021: 42) But this complexity is also framed, ironically, by a mantra that ‘there is no alternative’: that it is easier to imagine the end of the world, as Mark Fisher suggested (2009), than the end of the present system of economic and social policies. It is perhaps no surprise that this era sees the rise of what has been termed ‘post-truth’ (the complications of which as a concept will be discussed below), and the manifestation of practical ambiguities into the notions of critique, truth and evidence. This all means that the correct distance Benjamin refers to, seems far from obvious. But more than that: the means by which we are to find it seem exhausted, tired and rather too obvious.

As a result, a number of concerns arise regarding the circulation of and attitudes to knowledge, the ownership of authority and the status of ‘critique’ and ‘facts’. Such concerns are built upon a combination of advances in digital media and the accessibility of information, and longer-term political and philosophical issues within the applied professions themselves regarding the role of expertise and the limits of practitioner roles. But they are also key to speculating, as the theme of this journal issue asks us to do, on possible social work futures. After all, questions of professional reflexivity, evidence and insight within social work – which are all key to social work education – take place within the broader contexts of conflicting knowledge systems, political performativity and the thorny issue of post-truth. There is, then, a potential dialogue to take place between theorists attempting to rethink the notion of criticality, and professionals and students within social work who are constantly reminded to employ critical thinking to navigate this world through their practise; yet they are also in the grip of the urgencies of welfare crises, sparsity of resources, mounting caseloads and so on, all framed within a vocabulary of urgency which can sit uneasily with a number of models underlying critical thinking, and their emphases on taking ones time to ensure robust and rigorous distance (see Grimwood 2020).

Within such a context, what is the role of critique in social work, and how can this speak to the philosophical problems of critique? To answer, albeit schematically, this paper begins by presenting a model for conceptualizing the rhetoric of critical thinking in social work, with a particular interest in how criticality is managed within social work education. It then explores the limits of this model within broader interdisciplinary debates on criticality, addressing the contemporary problems with ‘post-truth’ and challenges to critical thinking. Finally, it draws upon the insights from existing debates on ‘post-criticism’ to suggest possible sites of future exploration regarding the status of critical thinking within social work, and its potential dialogues with broader disciplines.

Critical atmospheres

In asking this question, I am not referring to one model, measurement or assessment, but rather am interested in a certain atmosphere or attitude which runs throughout exhortations of criticality, whether in theory or in practice. Literary theorist Rita Felski summarises such an atmosphere as the way that critique assumes an unchallenged place: ‘Critique, it is claimed, just is the adventure of serious or proper “thinking,” in contrast to the ossified categories of the already thought. It is at odds with the easy answer, the pat conclusion, the phrasing that lies ready to hand.’ (Felski 2015: 7) In this way, she continues, ‘rigorous thinking is equated with, and often reduced to, the mentality of critique.’ (2015: 15)

Despite the marked differences between the disciplines, we nevertheless find in health and social care a similar atmosphere to what Felski describes in literary theory. These are, just as for Felski, not theoretical commitments or disciplinary limits, but distinctive atmospheres of critical thought. After all, as Kahlka and Eva have argued, while calls for enabling critical thinking ‘are ubiquitous in health professional education,’ there is nevertheless ‘little agreement in the literature or in practice as to what this term means and efforts to generate a universal definition have found limited traction.’ (2018: 156; see also Boostrom 2005; Heron 2006; Milner and Wolfer 2014). Surveying the literature we will find, for example, suggestions that ‘the best representation almost always lies beneath the surface of the given information’ (McKendree et al. 2002: 59); that critical thinking ‘looks beneath the surface of knowledge and reason’ (Brechin et al. 2000: 56); it encourages ‘asking questions designed to make the invisible visible’ (Gambrill 2012: 11); that it is rigorous thinking with a ‘purpose’ or a ‘value base’ (Facione 2013; Gambrill 2012, 2018; Mason 2007), even if the descriptions of such a purpose or value base come close to repeating the same mantras of critique itself. Indeed, it is not uncommon to find in the literature definitions which double down on the term: ‘critical thinking is the systematic application of critical thinking’ (Gibbons and Gray 2004: 20); ‘“critical thinkers” have the dispositions and abilities that lead them to think critically’ (Hitchcock 2018: online; Paul 1995). Furthermore, alongside these common definitions the atmosphere of criticality mingles, sometimes interchangeably, with other related elements which challenge stagnancy and ossification: clarity, creativity, decision-making, evaluation, reasoning, reflection and significance. Perhaps it is unsurprising that there has been little agreement on definitions.

Following Felski, I would argue that while these voices may all spring from different models of critique, their themes all depend upon a similar ‘rhetoric of defamiliarization.’ (Felski 2015: 7) While such a rhetoric facilitates the kind of ‘distance’ that Benjamin suggested in my opening quote, it has an added effect of positioning critical thinking in its own, exceptional, space. In other words, this rhetoric suggests that when we apply critical thinking, everything can be defamiliarized – except critique. Because critique is inherently opposed to convention, it is not subject to the same scrutiny it insists on for the everyday world of practice. As a result, Felski argues that the ‘social worth’ of critique can, it seems, ‘only be cashed out in terms of a rhetoric of againstness.’ (2015: 17, emphasis original) Critical thinking has, in her view, developed a disproportionate focus on critique and suspicion, at the expense of thinking as an embodied practice in time and space. Such againstness can be seen, for example, when Gambrill presents the hallmarks of critical thinking in health and social care as a series of binary oppositions. These include clear versus unclear, relevant versus irrelevant, consistent versus inconsistent, logical versus illogical, deep versus shallow and significant versus trivial (2012: 11). Critical thinking, she goes on, is about revealing ‘evidentiary status’ through questions that are too often not asked, questions which take us beyond the immediacy of the decision and either back to its origin (or its evidence) or forward to its effects (who it works for and how). In doing so, this introduces a distance between the critical thinker and the object or moment of critique; and it is this distance which speaks to the exceptionalism of the critic, because it allows them to step outside of their immediate context. However, it is clear that Gambrill’s dualisms are constructed entirely from the perspective of one side: the side of the critic. That is to say, the presentation of these binaries results in a clear, consistent and logical account of how critical thinking ‘works.’ It is not so much a description of critical thinking, in that sense, but rather a description of a world shaped by the primacy of a certain mantra of detached and rational observation.

As Bruno Latour points out, however, the problem with such foundational principles is that they are not designed to be challenged. For example, the assumption that ‘objectivity’ defends particular critical views. But ‘as soon as objectivity is seriously challenged […], it becomes desirable to describe the practice of researchers quite differently,’ because it lacks tools of defence other than repeating its own significance (Latour 2013: 11). Hence, in presenting critical thinking in the way Gambrill does – that is, repeating the traditional view that criticality is ‘restricted to one side of the intellectual encounter, and everyday thought is pictured as a zone of undifferentiated doxa [opinion]’ (Felski 2015: 138) – some of its inherent problems in practice are obscured.

This can be problematic for social work, as Jan Fook (2022) points out, in that part of learning to be a critically reflexive practitioner is to put themselves into the context of a situation, utilising their own understanding and their relational and interpersonal skills to form a holistic practice situated in specific contexts. However, while it is tempting to reduce this to another dualism (reflexive practice versus positivist critique), this may risk a) overlooking why such a rhetoric of againstness is so persuasive to the idea of criticality in the first place, and b) inadvertently repeating that againstness (that is to say: reflexive practice is persuasive because it is not positivist critique). Indeed, the point about criticality bearing a certain rhetoric, or a certain atmosphere that privileges certain actions, instincts and performances (Sedgewick 1997) goes beyond the more obvious problems with overtly positivist accounts of critical thinking (of which there are, of course, many, largely due to the history of critical thinking’s entry into the curricula of the applied professions – see Paul, Elder and Bartell 1997). It also affects the broader critically interpretative activities at the core of relating theory and practice. For example, when Stepney and Thompson (2021) boldly argue that ‘applying theory to practice’ (which they argue is the conventional educational approach) is replaced by ‘theorising practice,’ they assert that ‘if carried out with skill and critical thinking, then theorising practice leads to informed practice.’ (p. 155, my emphasis) Addressing the complexities of the social world that confronts the practitioner, they argue that when ‘dealing with situations of conflict and uncertainty practitioners cannot simply draw upon their knowledge base in a direct, linear or prescriptive way, but must engage in a process of critical exploration.’ (Stepney and Thompson 2021: 154, my emphasis) What is critical thinking, though, in this sense? It is nothing more than ‘the ability to question, probe and explore beneath the surface’ (2021: 159). In this way, even a decidedly non-positivist account retains the notion of critique as an exercise in analytic process; an unmasking or excavating act, involving a subject probing an object, and which is developed and enhanced with enough training or encouragement.

With this in mind, we can answer out starting question regarding the role of critique in social work via the alignment of critical thought with rigorous thought. While such deployment may involve different theories and traditions, there tends to be three interlinking sites where criticality is particularly prominent within social work education:

1. Critical thinking as a requirement or hallmark of professionalization. Within this dimension, criticality emerges in learning outcomes and marking rubrics, continuing professional development courses, and finds its medium in a range of texts from the basic ‘how to write an essay in health and social care’ to more in-depth analysis of and models for critical thinking.

2. Critical thinking supporting evidence-based practice and delivery innovation. Here critique forms part of the established methods for evaluating practice and policy, and utilising such evaluations to inform potential changes to practice, and further evaluation of new ways of working: separating research designs according to validity and reliability, for example, or insisting on utilising current evidence to support best practice. This form of critical social work is described by Gray and Webb (2009) as a ‘broad’ account of criticality, rooted in reflection and finding alternatives while leaving the broader structure of both society and its knowledge hierarchies in place.

3. In contrast to the ‘broad’ account, Gray and Webb suggest a ‘narrower’ version is an active critique of core service delivery and the link between practice, culture and politics. Social work has, at least since the 1960s, shared many of its fundamental tenets with critical theory, feminist theory and aspects of post-structural political philosophy. The third critical site, then, is the use of critique to challenge domination and oppression at not just personal, case levels, but at interpersonal and structural levels as well. Critique allows the diverging forms of domination to be identified, some of which involve not just external force but also what Fook describes as ‘internal self-deception’, a hallmark of the ‘false consciousness’ of classical Marxism (Fook 2002: 17); Fisher and Dybicz (1999) note that the rise of critical reflection in social work, utilising the historical basis of practice including its relation to broader power structures, was a response to the a-historical rise of critical thinking as a mark of professionalisation in the 1980’s and 1990s; likewise, Brookfield (2009) suggests that critical reflection is only really ‘critical’ if supplemented with a critical and/or social theory within it. This informs approaches such as Shor’s ‘critical pedagogy’: where learning and teaching directly engages with:

habits of thought, reading, writing, and speaking which go beneath surface meaning, first impressions, dominant myths, official pronouncements, traditional cliches, received wisdom, and mere opinions, to understand the deep meaning, root causes, social context, ideology, and personal consequences of any action, event, object, process, organization, experience, text, subject matter, policy, mass media, or discourse. (Shor 1992: 129).

Situating criticality in social work

This is not the place to go over the various debates that inform these sites. Instead, my interest is, first of all, how criticality is deployed within them as different forms of sense-making. By exploring this, it is possible to unpack the notion of what ‘post-critical’ might mean to social work.

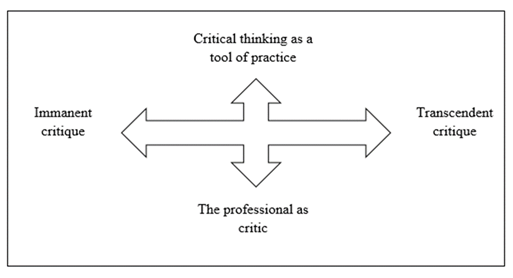

While these describe the primary sites where criticality is significant for social work, the form of critical thought is not as tidy to summarise. Instead, it is better to think of critical thinking as emerging in social work along a continuum, with its most instrumental use – as a way of improving frontline decision-making ‘in the moment’, what was described in dimension (a) above – at one end, dovetailing into guides for good practice; and at the other end broader critiques of welfare provision and policy, those of the academic or the activist, which dovetail with the arguments of social and cultural theory and constitute critique as an endpoint rather than a means (dimension (c)) (see Figure 1).

Figure 1

It may be said, with tongue slightly in cheek, that the distinction between professional qualification – typically marked, in most countries, by a higher education degree – and vocational training is the presence of the word ‘critical’ in the learning outcomes. As McKendree et al. noted, criticality has increasingly featured in educational standards for health and social care: it is a ‘generic skill to be learned in classes and transferred from one to another’ (2002: 57). This alerts us to the dual dimension of criticality in the professions: on the one hand, indicating or qualifying a depth of skills and knowledge which is legitimised by institutions and organisations (through qualifications, career pathways, Continuing Professional Development and research), and on the other hand applying a depth of inquiry which, in many cases, challenges those same institutions (through theoretical exploration, particularly through critical theory, and political dimensions of practice such as the various forms of ‘critical’ social work which move from ‘critical thinking’ as a tool to something more like ‘social criticism’).

The indication of skills, on the one hand, and their application, on the other, are not inherently opposed; they simply perform different functions. As such, identifying the dual dimension of criticality here is not cynical, but rather necessary, insofar as critical thinking is embedded within the systems of professionalization. It also helps to show how critical thinking naturally lends itself to the differing, and sometimes conflicting, dimensions mapped above. For Toner and Rountree (2003), the politics of critical theory and the practicalities of critical thinking are necessarily interdependent, given that they both centre on analysis and reflection. Although noting that an awareness of broader critical theories is not necessary to be a critical practitioner, Glaister, too, situates ‘critical practice’ at the intersection of analysis, action and reflexivity; and argues that critical practice entails understanding individuals ‘in relation to a socio-political and ideological context within which meanings are socially constructed.’ (2008: 17) However, it is also important not to simply role these two different dimensions into one. This is in part due to disciplinary objections, such as the recurrent (and somewhat tiresome) criticisms that social work education is too focused on social theory than face-to-face interventions (Narey 2014). But it is also important to note that either end of this vertical continuum relate to very different aspects of professionalization.

Because I am grouping together a relatively varied group of practices on this continuum, it is useful to picture another continuum, running across the first, this time concerning the concept of criticism being employed. Here, I use two different philosophical concepts to mark out either end: ‘transcendent critique’ on the one hand, and ‘immanent critique’ on the other. These concepts do not describe methodologies, but rather the atmospheric relationship between critique and practice in general. Transcendent critique positions the role of critical thinking as enacting a relatively unchanging set of conditions or principles, whether this is an established set of properties for factual knowledge, as utilised in Evidence-Based Practice (EBP), or a principle of reason that underlies activity such as much of the varied responses to Kant’s philosophy have provided (for example, the later Habermas’ notion of communicative rationality). Immanent critique, meanwhile, is tasked with unpacking the hidden contradictions in the systems we use. This involves assessing a practice on its own criteria for rationality and demonstrating how it falls short of this. In this way, rather than stand outside of the world, it constitutes a form of ‘insider critique’ employed not just by those traditions influenced by Marx, Foucault, Deleuze and others, but also applied methods such as Action Research (Pearson 2017). In short, if transcendent critique draws on external rules by which an object (or case, or social structure, or theory…) is critically examined – for example, whether it well-evidenced with reliable data, or whether it is governed by rational or dialectical principles etc. – then immanent critique looks for the instabilities within those objects that are linked to the broader systems that create it.

Philosophically, these two approaches to critique seem at odds, and indeed at the further points of each end of the continuum are very much opposed. However, the notion of critical professionalism tends to fluctuate, necessarily, between both. Hence, some critical approaches will sit at particular points on the matrix (the more instructional textbooks on critical reasoning, for example, will tend to be found near the top right-hand corner). Others are perhaps more difficult to situate, owing to the different ways in which criticality emerges as part of professional practice. In such cases, the point of the diagram is not to insist on a definite position, but rather to note how this difficulty is constituted, and what contributes to it.

Criticality in question

We have already seen, in the discussion on how problematic a definition has been for social work education, how critical thinking can operate as something of a floating concept within both practice and education, with not only competing commonplaces of what criticality is or should be, but also competing claims as to how it affects different contexts. Indeed, the reason for the apparent transferability of critical thinking skills is rooted in the fact that, rather than simply being a tool or instrument for better thought and practice, critique carries with it associated habits, rituals and figures which constitute the atmosphere of critique. It is calling attention to these associated habits that have led some to question the ways in which criticality is positioned.

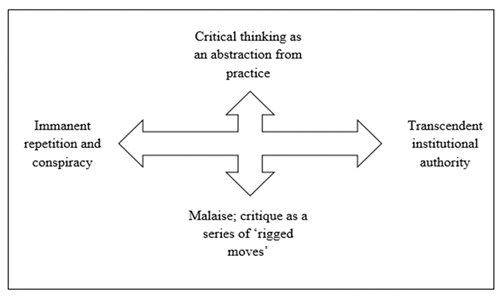

Having provided a model of criticality in social work, then, we can now return to the starting point of the paper: that critique is now in question. To this end, figure 2 sketches out how these problems emerge when each of these critical coordinates stagnates. Some of these are well-known in social work theory already: the question of EBP as an appropriate ground for practice, for example, has a long history of debate going back to the late 1970’s. But here, I want to concentrate on the ways in which more general and interdisciplinary discussions on the nature of critical thinking might affect its relation to social work.

Figure 2

It is perhaps a testament to how established the idea that critical thinking is good and necessary, that when it is challenged the response is often to simply re-double one’s efforts in being ‘critical’ in the conventional sense: without investigating the relationship between the two or considering the questions one might raise of the notion of ‘the critical’ being employed. Perhaps the most common example of this, returning to our introductory problem, is when the prospect of ‘post-truth’ emerges within the context of health, social care or social work, and the premises of critical thinking itself is under fire. In an editorial of International Health Promotion, for example, Michael Sparks provides a summary of what we must now recognise as the stock response, best summarised by his section headings: the first is ‘Maintain our Research Standards’; followed by ‘Strengthen our Institutions.’ The way to combat challenges to evidence standards and critical reasoning is to simply do continue to do it. Sparks, like several theorists responding to the advent of post-truth, insist on a form of transcendent critique invested in scientific method to dispel disinformation and competing truth claims. In part, this is due to the insistence on following the rather unfortunately mis-informed definition of post-truth that the Oxford English Dictionary decided upon, that was ‘relating to or denoting circumstances in which objective facts are less influential in shaping public opinion than appeals to emotion and personal belief’. Of course, such a definition rides roughshod over the complexities of establishing ‘objective fact’ that provide ongoing debates in both philosophy and social work (how are the facts of a social work case ‘objectified’? What relations, institutions and power dynamics does this involve, and how are they, in Ken Moffat’s words, ‘entrenched within the social body’? (1999: 219)). The definition ignores the work of feminist theory in addressing the early modern division of reason and emotion, and the separation of the political from the personal. In short, it insists that ‘post-truth’ is in fact an ‘anti-truth’ (opposed to objective fact), rather than a mutation of how truth is understood and used, much in the way that post-modernism was to modernism. In doing so, what goes unsaid is that ‘post-truth’ is a general term that is used to cover a wide range of shifts and changes in the way critical thought is applied: it is the use of a non-contingent term to cover a number of contingent practices, and in this sense, the term ‘post-truth’ is a performance of post-truth in itself.

This said, the absence of criticality in decision-making is a frontline concern: whether this is through the ‘top-down’ lack of evidence-based working to inform social policy (Speed and Mannion 2018; Smith 2017), or the ‘bottom-up’ availability of information and disinformation for both service users and practitioners to challenge the basis of their support; something the recent Covid-19 crisis brought to the fore (López Peláez et al. 2020, Hopf et al. 2019). The problem emerges, though, when the same standards and institutions that Sparks insists we re-emphasise might also be, in some way, complicit in the complexities of post-truth. Frieder Vogelmann has made this point clearly when he points out the paradoxes of the very idea of post-truth:

those diagnosing a “post-truth era” often replace the hard work of justifying their truth-claims with appeals that we must learn to trust again […] our political elites, our fellow citizens and, most of all, our scientists. Yet which experts, which scientists, which politicians and who of our fellow citizens should we trust? Without explaining how we can discriminate between blind faith and trust, calls for a renewal of the virtue of trust turn into calls for being less critical – certainly a bad strategy if we really lived in a “post-truth era” with its reign of “fake news” and phony experts. (2018: 21)

For Vogelmann, the exclusive focus on a particular model of ‘truth’ as a resurrection of unbridled positivism leads to the idea of post-truth being remarkably shallow and ill-fitting. Rather than pursue rigorous critical activities, he suggests, we are simply asked to ‘trust’ those who have traditionally held political and epistemological authority. This would overlook, for example, the conflicts between practitioners around what constitutes ‘best practice’, the instructive debates around how social work should be theoretically framed, or the realities of implementing models of best practice abstracted from their original contexts; not to mention the insights of postmodern social work. Social work is historically formed out of just such competing claims to knowledge, as can be seen even today with, for example, the continued debates over the voice of the service user in decision-making.

Likewise, the exclusive attention on knowledge as the end-point of critical thinking means that the social contexts surrounding the conditions by which post-truth has become a popular term are often overlooked or downplayed. This is made manifest when the responses to post-truth, and the recommendations on what should be done, appear to reflect many ‘felt’ or ‘instinctive’ truths on the side of theorists and practitioners alike. For example, writing on the MacMillan International Higher Education blog, Louise Katz writes of the problem with ‘critical thinking’ becoming a buzzword. While ‘the most commonly presented argument for the importance of teaching critical thinking at university is that it is an indispensable tool for sorting through the roar of ideas with which we are inundated daily,’ Katz suggests a need for students and practitioners to go further:

In order to think critically, we have to be willing to question ourselves, our motivations, and our belief systems; in other words, we have to attempt to step outside ourselves and work out why it is that that we believe what we believe. Only then can we begin to approach an idea or an issue with clear eyes. […] This means exercising a desire to see to the truth of a matter. We have to desire truth. (Katz 2019)

Katz’s argument is one of many examples where particular tropes and images of critique are employed to enhance their persuasiveness: notably, the need to look behind or beyond the immediate circumstances (‘steeping outside ourselves’) which implies that clarity can only be achieved via detachment. Notably, Katz draws on the image of desire – we can’t just want truth, we have to desire it! – which suggests a far more intimate connection, deeply ingrained in selfhood; but also, an image which seems at odds with the prior command to step away from the immediacy of our ‘self.’ In such cases, it is once again a pervading atmosphere of a particular type of criticality which comes to the fore in this rhetoric: something which is, I would argue, underexplored in the current literature.

Affects beyond critique: rhetorics of suspicion

I call attention to this, not for the sake of criticising Katz, but rather to note how this atmospheric tension sits within the premise of transcendent critique when it is challenged by deceptively complex terms such as ‘post-truth’. The roots of contemporary EBP are found in Archie Cochrane’s evaluation of the National Health Service in England, Effectiveness and Efficiency: Random Reflections on Health Services (1971), which promoted the use of the Randomised Control Trial (RCT) and subsequently gave rise to the Cochrane Collaboration Tool for systematic reviews of current available research on a given health topic; reviews which now form the bedrock of EBP across the allied health professions. In social work, meanwhile, a number of papers appeared challenging the evidence base of social work interventions around the same time (see Fischer 1973; Pincus and Minehan 1973). Cochrane’s original book makes for an interesting read when compared to the industry that EBP has since become: he approaches the topics of effectiveness and efficiency by freely admitting his own biases, including his emotional investment in health provision; he situates the state of medical treatment within a narrative history which includes his own experience in prisoner of war camps, summarises the expectations and beliefs of ‘the layperson’, and includes an astute observation on the role of the Medical Research Council in ignoring applied research in favour or ‘pure’ and how this contributes to the effectiveness of care.

This is some ways an incidental observation, and I do not want to revisit the EBP debate in social work itself. I raise it instead to make the simple point that the presentation of the case for EBP – its rhetoric, in effect – has always depended upon elements which are effectively outside of its own processes. This is because the basis of transcendent critique is that it takes place from a position outside of a given ‘real world’ (hence transcends the immediacy of the real in a kind Archimedean view from nowhere); which is also why it insists on the need for ‘trust’ in institutions to work effectively.

The opposite end of the continuum, meanwhile, which insists on the immanent critique of existing systems, searching for the concealed contradictions and structural tensions that uphold oppressive contexts for service users, can also be said to have reached a point of malaise. Across different theoretical disciplines, theorists have suggested critical thinking has itself stultified and become only a staged performance. It has therefore become a well-rehearsed exercise of problem-pointing, which does little to effect actual change on either a societal level or for individual service users. We have already seen this risk in our earlier discussion of textbook uses of critical thinking, a tension which was taken up by Bruno Latour, in a now-famous paper which asked ‘Why Has Critique Run out of Steam?’ Here, Latour presents critique as a form of self-knowledge, set against the naïve optimism of the Enlightenment that knowledge alone will simply expand for the better. However, while this calling out the problems of positivist and scientistic assertions of the primacy of ‘facts’, he argues that this form of critical self-knowledge falls into traps of its own design. It produces what amounts to an endless cycle of critique – adding ‘iconoclasm to iconoclasm’ and practising a form of ‘instant revisionism’ (2004: 228) where every fact must be doubted – risks leaving intellectual pursuit as ‘like those mechanical toys that endlessly make the same gesture when everything else has changed around them.’ (225) A non-reflexive blindness, Latour argues, has been built into the suspicions of critique, which unwittingly creates a set of mechanical clichés; undertaking critique is simply ‘to go through the motions’ (226).

If the task of critical thought has become institutionally embedded as debunking reality as a sign or mask of something else (complexity, ideology, power, hegemony etc.) then, Latour points out, these principles manifest themselves in contemporary culture in the form of conspiracy theories. In their ‘mad mixtures of knee-jerk disbelief, punctilious demands for proofs, and free use of powerful explanation from the social Neverland,’ they deploy the same ‘weapons of critique’ – distrust, suspicion, the need to unmask and expose – which were originally meant to protect us from just such fantastical arguments (230). As a result, Latour finds

something troublingly similar in the structure of the explanation, in the first movement of disbelief and, then, in the wheeling of causal explanations coming out of the deep dark below. What if explanations resorting automatically to power, society, discourse had outlived their usefulness and deteriorated to the point of now feeding the most gullible sort of critique? (Latour 2004: 229-30)

Post-critical social work?

Latour is being deliberately polemical, but his point is worth considering. It is sometimes difficult not to read the myriad of diagnoses of the fate of social work, typically rooted in the behemoth of neoliberalism, and ask similar questions. Just as there are the well-known and powerful figures of post-truth – the policymaker motivated by economic cost-cutting rather than real, existing welfare; the ill-informed service user voting for cuts to their own provisions, and so on – there are similar figures on the side of the critical social worker: the ‘subversive caseworker’ or the transgressive practitioner, operating in between the lines of panoptical human services management (see Schram 2015). What I am suggesting here is that, in at least a small way, these figures are products not just of the politics of social work, but also the worn-out models of criticality that it employs, wherever such models sit on the matrices above, and the rhetorical atmospheres in which they emerge – whether this is in the classroom, the textbook, or the journal article. But how do we go about criticising critique, without being caught up in an endless cycle of criticism?

It is perhaps common to expect a set of ‘practice recommendations’ at this point in the paper, but my suggestion is that is the post-critical discussions raise one thing, it is that the future of social work education would do well to question such immediate expectations. It is important to acknowledge that while the post-critical debate is relevant to social work education, this is not in the conventional sense in which a new addition is made to the ‘theory supermarket’ which educators pick and choose from as they want; itself an extension of neoliberal ‘choice’ (Grimwood 2016: 132-3). It would also be dangerous to assume that discussions in rhetoric, literary theory and philosophy will map on to social work concerns as neatly as a journal article-length paper allows.

Instead, such an interdisciplinary dialogue is not simply about providing practice pointers, but asks questions of the foundational concepts at work in education (be this social work or philosophy). In this way, as a starting point for considering what kind of dialogue social work and critical theory might have on these issues it is necessary to think of those areas of social work education – and perhaps, more broadly, in practice – where ‘criticality’ is deployed, and how the tenets of the post-critical debate would inform this. Here, I suggest three in particular.

1. Critique is not just about matters of fact, but matters of concern. Latour concludes his deconstruction of critique by suggesting the key problem is an almost relentless prioritising of facts; a prioritising which can also be seen in the numerous texts that respond to post-truth by insisting on a renewed emphasis on scientific method. It can also be identified in the relationship between social work and ‘data gathering’, particularly the role of data and case management systems. Following Latour, it can be seen that there is nothing inherently wrong with a ‘matter of fact’; and, indeed, the recommendations of organisations such as the American Academy of Social Work and Social Welfare’s report Harnessing Big Data for Social Good (2015) demonstrate ways in which sharing information can lead to better outcomes. The problem is when ‘fact’ becomes the dominant figure of critical thought: when ‘information’ displaces the very relational aspects that made that information worthy of gathering in the first place. When this happens, critical thinking is shaped towards certain activities, postures and distances at the expense of others. Latour suggests that matters of fact are only one subset of a broader category of matters of concern. These are ‘gatherings’ of ideas, forces, figures and sites in which ‘things’ (rather than ‘facts’) emerge and persist, precisely because they are cared for or worried over. He concludes optimistically that the future critic must be ‘not one who debunks, but the one who assembles […] not the one who lifts the rugs from under the feet of the naïve believers, but the one who offers the participants arenas in which to gather’ (2004: 246) Criticality, in this sense, is an awareness of how something has been made ‘provides a rare glimpse of what it is for a thing to emerge out of inexistence’ (2005: 89), and as such the question we ask is not whether it’s constructed or not – clearly, things in the world are made, whether by humans or other forces – but rather if it’s constructed well or badly. While he notes that it has become more common in both the social and natural sciences to equate ‘constructed’ with ‘not true’; and, subsequently, this leads to a ‘most absurd’ command: ‘“Choose! Either a fact is real or it’s fabricated!”’ (Latour 2005: 90-1) This is a false dichotomy: after all, proving facts in clinical interventions depends upon carefully constructed methods and data collection systems, which reflect the concerns of those undertaking them. As such, the post-critical move here is to shift towards attending to such concerns more openly. It should be noted that this is not just a case of pressing that ‘context matters,’ which has, after all, become a common mantra for social work education, particularly within discussions of appropriate knowledge forms and interventions relative to service user circumstances, culture and demographics (see, for example, Nadan et al. 2015; Reamer 2014; Graham et al. 2012). Instead, the challenge of the post-critical approach is to challenge how satisfactory the category of ‘context’ is an explanatory tool. This is not to dismiss context, but rather ask whether a focus on ‘facts’ obscures some of the wider ‘concerns’ when deciding where the line between context and action exists. Consider the age-old tool of social work education, the ‘case example.’ Here, textbooks will often present short descriptors of individuals and their situations in order to ask students to think through how they would engage as social workers. In doing so, such examples invariably include contextual categories (age, gender, ethnicity) as well as histories and ‘background’ information. The point is not that any of this is uninteresting; but as Felski suggests these categories can often be used as kind of container to ‘hold fast’ that which is under scrutiny (1997: 155). In this way, ‘context’ can be used as a short-hand way of closing a discussion down, rather than remaining as open to interrogation as whatever it is being contextualised in the way that Fook (2022) suggests.

2. Critique involves a performance of knowledge. We noted earlier that knowledge was often considered to be the endpoint of critical thinking. In her famous essay subtitled ‘You’re so paranoid, you probably think this Introduction is about you’, queer and feminist critic Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick contests this by suggesting that ‘knowledge does rather than simply is.’ Rather than using critical thinking to support a reliable knowledge-base, she suggests that the real interest in knowledge should be what ‘the pursuit of it, the having and exposing of it, the receiving-again of knowledge of what one already knows’, because this is more meaningful at in our localised decision-making (Sedgwick 1997: 4). Such an observation that knowledge does things in specific situations is not radical (see Dore 2018a for a reflection on how this emerges in social work practice via forms of epistemic injustice). However, Sedgwick argues that understanding knowledge as a something that ‘happens’ in local contexts is blunted by the deployment of critical thinking as a mode of suspicion. While in the humanities this alignment is rooted in a particular tradition of radical thought – often referred to as the ‘hermeneutics of suspicion’ – it can likewise be seen in the straightforward injunctions in critical thinking manuals to ‘look beyond the surface’ for the reality of a situation; whether this reality be the power structures of neoliberal late capitalism in welfare provision, or merely a more rigorous solution to a problem that is not immediately self-evident. Sedgwick’s point is that while there is clearly much to be gained from this approach, such a mentality has become so habitual it ‘may have made it less rather than more possible to unpack the local, contingent relations between any given piece of knowledge and its narrative/epistemological entailments for the seeker, knower, or teller.’ (1997: 5) This is because suspicion becomes a form of paranoia: think of how ‘neoliberalism’ can become something of a shadowy ogre that explains everything that is wrong in one blunt and somewhat vague concept; often interchanging between a set of economic policies, an ideology, a political rationality, a mode of subjectivity or all of the above (see Watts 2021). As with the problem of context, the issue here is not with using social work education to identify the wider social forces affecting practice. Rather, it is the anticipation of a difference between the surface and depth that this can carry with it; and, in anticipating such a difference, the investment of a form power in exposing something behind an appearance. We risk being left with Jacques Ranciere’s pithy statement on the often-unacknowledged side of critique: ‘where one searches for the hidden beneath the apparent, a position of mastery is assumed.’ (2004: 49) The problem with this assumption of mastery is not only the assumption of naivety on behalf of those who are not suspicious enough – those who will be shocked by the exposing – but also that some formations that social work faces, engages with and seeks to overcome are, in fact, premised on their visibility, rather than their hidden-ness. There is, after all, no need to identify hidden power structures in a van driving around London with telling illegal immigrants to go home; and in Welfare Words (2019), Paul Michael Garrett has tracked the shifts in policy discourse to overtly vilify terms such as welfare dependency and anti-social behaviour. Likewise, suggesting hidden neoliberal agendas may do little to inspire social work students who encounter claims that this is ‘simply how it is done here’ when on placement, regardless of the currency of evidence. Insisting on traditional critical thinking approaches in such situations is more likely to deepen divides rather than pay heed to the different performances of knowledge at stake in workplace culture; but in paying heed to these in detail, different (and more effective) approaches to transform those practices may appear. Sedgwick herself argues for a ‘reparative’ approach to critique: one that, rather than adopting an interrogative posture that seeks to outsmart through critical distance, to look instead at what knowledge does in terms of its innovations, localised empowerment and social changes, however small. This means resisting, for at least a moment, the desire to fall back on to the familiar bogeymen of welfare, and to question how much of this is prefigured by expectations of what ‘being critical’ requires. In this way, Sedgwick’s approach resonates with Straub’s account of criticality as:

a desire to learn something new, to be surprised by what I see in a text, to feel the shock of cultural and political unfamiliarity. […] [W]hile I still want to know where I am starting from when I create an interpretation, I would rather not know where I am going. (Straub 2013: 140)

3. Criticality is more mood than method. Much of the literature on post-critique has argued for more attention to the surface of experience, or a more affirmative approach which moves us away from the ‘hermeneutics of suspicion’ which have dominated critical theory and, therefore, the application of critique into practice. If critique has been dominated by assumptions of hidden depths to any surface – depths which the critic is expected to retrieve, clarify, and re-present – the response is often to move to a more conservative position: replacing ‘depth’ with ‘surface’, adopt a ‘what you see is what you get’ approach and, in effect, return us to Latour’s matters of fact. The challenge for a post-critical social work, though, would be to explore the meaning of surfaces as surfaces. This would involve the banal, the ritualised and the ever-present but forgettable aspects of approaches to conceptualising care: or, in other words, what I earlier referred to as the atmospherics of criticality. These constitute an active process of knowing that is, after all, precisely what social work knowledge does (see Dore 2018b). This requires a shift in the register of critical thinking, not to simply swap depth and surface around (which risks simply replacing critical suspicion with wilful naivety), but rather focusing on the rhetorical, affective and atmospheric aspects of critical reflection.

When Felski refers to a ‘rhetoric of defamiliarization’ accompanying critique, she is using rhetoric in a rather disparaging way. However, rhetoric is not necessarily a benign evil, but is instead the study of what makes things persuasive. Indeed, the defamiliarization that Felski refers to is a legacy of the notion that critique must be rationalist and requires holding a critical ‘position’ (similar to what Gambrill described earlier), which often obscures or neglects mood, emotion or disposition. In other words, paying attention to the surface means understanding the moods of critical thought, and how these affect its performance within practice. Such an understanding does not do away with suspicion altogether. Rather, it brings to light aspects of sense-making and localised criticality that may otherwise be dismissed. Lauren Berlant (2011), for example, writes of the significance of affective attachments in structuring fantasies of upward mobility, job security, and political equality for those in poverty; a ‘cruel optimism’ that is central to the premise of late capitalist society. Taken on their own, these seem straightforwardly irrational; it is only when placed within the cultural rhetoric that surrounds it that they might be understood as a form of sense-making.

When faced with the prospects of a post-truth age, or the problematic issues sparked by identity politics, newly prescribed academic orthodoxies and the spirit of social work remaining under the auspices of neoliberal managerialism, one avenue is to encourage a revival of the critical and vocal spirit that has always been part of social work history (see, for example, Fenton and Smith, 2021). But it is important to be vigilant as to the ways in which a critical spirit can itself contribute to malaise, and lead to dead ends in social, professional and political thought. However, applying a critical lens to critical thinking, and engaging in a dialogue with the debates around post-critique, suggests that the applied and localised practices of social work education offer the potential to think and act through such a critical malaise.

References:

American Academy of Social Work and Social Welfare (2015). Harnessing Big Data for Social Good: A Grand Challenge for Social Work. Available at https://grandchallengesforsocialwork.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/WP11-with-cover.pdf

Benjamin, W. (1928 [1996]). ‘One-Way Street.’ In Selected Writings Vol 1, ed. Jennings, M. et al., Cambrdige: Harvard University Press.

Berlant, L. (2011). Cruel Optimism. Durham: Duke University Press.

Boostrom, (2005). Thinking: the Foundation of Critical and Creative Learning in the Classroom. New York: Teacher’s College Press.

Brechin, A., Brown, H. and Eby, M. (2000). Critical Practice in Health and Social Care. London: Sage

Brookfield, S. (2009). ‘The Concept of Critical Reflection: Promises and Contradictions.’ European Journal of Social Work, 12(3), pp.293–304.

Cochrane A. (1971). Effectiveness and Efficiency: Random Reflections on Health Services. London: Nuffield Provincial Hospitals Trust.

Dore, I. (2018a). ‘Doing Knowing Ethically – Where Social Work Values Meet Critical Realism.’ Ethics and Social Welfare 13(4), 377-91.

Dore, I. (2018b). ‘Social work on the edge: not knowing, singularity and acceptance.’ European Journal of Social Work 23:1, 56-67.

Facione, P. (2013). Critical Thinking: What it is and why it Counts. Millbrae: Measured Reason and the California Academic Press.

Felski, R. (2015) The Limits of Critique. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Fenton, J., and Smith, M. (2021). ‘“You Can’t Say That!”: Critical Thinking, Identity Politics, and the Social Work Academy.’ In H. Piper, and E-M. Buch Leander (eds.), Challenging Academia: A Critical Space for Controversial Social Issues, pp. 19-32.

Fisher, M. (2009). Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative? Winchester: Zer0 Books.

Fisher, R. and Dybicz, P. (1999). ‘The Place of Historical Research in Social Work.’ Journal of Sociology & Social Welfare, 26(3), pp.105–124.

Fook, J. (2002) Social Work: Critical Theory and Practice. London: Sage.

Fook, J. (2022) Social Work 4th ed. London: Sage.

Gambrill, E. (2012). Critical Thinking in Clinical Practice. Oxford: Wiley.

Gambrill, E. (2018). Critical Thinking and the Process of Evidence-Based Practice. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Garrett, P. (2019). Welfare Words: Critical Social Work and Social Policy. London: Sage.

Glaister, A. (2008). ‘Introducing critical practice.’ In Fraser, S. and Matthews, S. (eds.), The Critical Practitioner in Social Work and Health Care. London: Sage, 8-26.

Graham, J., Shier, M. and Brownlee, K. (2012). ‘Contexts of Practice and Their Impact on Social Work: A Comparative Analysis of the Context of Geography and Culture.’ Journal of Ethnic and Cultural Diversity in Social Work 21(2), 111-128.

Grimwood, T. (2016). Key Debates in Social Work and Philosophy. London: Routledge.

Grimwood, T. (2020). ‘The Rhetoric of Urgency and Theory-Practice Tensions.’ European Journal of Social Work 25(1), pp.15-25.

Grimwood, T. (2021). The Shock of the Same: An Anti-Philosophy of Clichés. London: Rowman & Littlefield.

Heinrich, S. (2020) ‘Medical science faces the post-truth era: a plea for the grassroot values of science.’ Current Opinion in Anaesthesiology, 33(2), pp.198-202.

Heron, G. (2006). ‘Critical Thinking in Social Care and Social Work: Searching Student Assignments for the Evidence.’ Social Work Education 25, 209-224.

Hitchcock, D. (2018). ‘Critical Thinking.’ Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Available at https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/critical-thinking/

Hopf, H., Krief, A., Mehta, G., Matlin, S.A. (2019). ‘Fake science and the knowledge crisis: ignorance can be fatal.’ Royal Society Open Science, 6(5), 1-7.

Katz, L. (2019) ‘Critical Thinking in a Post Truth Era.’ MacMillan International Higher Education blog. Available at: https://www.macmillanihe.com/blog/post/critical-thinking-louise-katz/

Latour, B. (2004). ‘Why Has Critique Run out of Steam? From Matters of Fact to Matters of Concern.’ Critical Inquiry, 30, pp.225–248.

Latour, B. (2005). Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

McKendree, J., Small, C., & Stenning, K. (2002). The role of representation in teaching and learning critical thinking. Educational Review, 54(1), 57-67.

Mason, M. (2007). ‘Critical Thinking and Learning.’ Educational Philosophy and Theory, 39(4), 339-349

Milner, M. and Wolfer, T. (2014). ‘The Use of Decision Cases to Foster Critical Thinking in Social Work Students.’ Journal of Teaching in Social Work, 34(3), 269-284

Moffat, K. (1998). ‘Surveillance and Government of the Welfare Recipient.’ In Chambon, A., Irving, A. and Epstein, L. (eds). Reading Foucault for Social Work. New York: Columbia University Press, pp.219-246

Narey, M. (2014). ‘Making the Education of Social Workers Consistently Effective.’ Department for Education. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/making-the-education-of-social-workers-consistently-effective

Ranciere, J. (2004). The Politics of Aesthetics. London: Continuum.

Smith, K. (2017). ‘Beyond ‘evidence-based policy’ in a ‘post-truth’ world: the role of ideas in public health policy.’ In Hudson, J., Needham, C. and Heins, E. (eds.) Social Policy Review 29: Analysis and Debate in Social Policy, Bristol: Policy Press.

López Peláez, A., Marcuello-Servós, C., Castillo de Mesa, J., Almaguer Kalixto, P. (2020). ‘The more you know, the less you fear: Reflexive social work practices in times of COVID-19.’ International Social Work, 63(6), 746-752

Nadan, Y., Weinberg-Kurnik, G., and Ben-Ari, A. (2015). ‘Bringing Context and Power Relations to the Fore: Intergroup Dialogue as a Tool in Social Work Education.’ British Journal of Social Work 45(1), 260-277

Pearson, J. (2017). Who’s afraid of Action Research? The risky practice of immanent critique.’ The Language Scholar Journal, 1, pp.1-21.

Sedgwick, E. K. (1997). ‘Paranoid Reading and Reparative Reading; or, You’re So Paranoid, You Probably Think This Introduction is About You.’ In Sedgwick, E. K. (ed.) Novel Gazing: Queer Readings in Fiction. Durham: Duke University Press, 1-37.

Shor, I. (1992). Empowering Education: Critical Thinking for Social Change. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Speed, E. and Mannion, R. (2017). ‘The Rise of Post-truth Populism in Pluralist Liberal Democracies: Challenges for Health Policy.’ International Journal of Health Policy Management 6(5), 249–25

Stepney, P. and Thompson, N. (2021). ‘Isn’t it time to start “theorising practice” rather than trying to “apply theory to practice”? Reconsidering our approach to the relationship between theory and practice.’ Practice: Social Work in Action, 33:2, 2021, pp.149-163.

Straub, K. (2013). ‘The Suspicious Reader Surprised, Or, What I Learned from “Surface Reading”.’ The Eighteenth Century, 54(1), 139-143.

Toner, J. and Rountree, M. (2003). ‘Transformative and educative power of critical thinking.’ Inquiry: Critical Thinking Across the Disciplines, 23, 81-85.

Vogelmann, F. (2018). The Problem of Post-Truth: Rethinking the Relationship between Truth and Politics. Behemoth: A Journal on Civilisation, 11(2), 18-37.

Watts, G. (2021). ‘Are you a neoliberal subject? On the uses and abuses of a concept.’ European Journal of Social Theory, 25:3, on-line.

Wilson, T. (2021). ‘An invitation into the trouble with humanism for social work.’ In Pease, B. and Bozalek, V. (eds.), Post-Anthropocentric Social Work. London: Routledge, pp.32-45.

Author´s

Address:

Tom Grimwood

University of Cumbria

tom.grimwood@cumbria.ac.uk