Education Inequality among the Muslims in India: Historical-Present Scenario

Vikram Singh, Indira Gandhi National Tribal University- Regional Campus Manipur

Introduction

In the current context, the Muslim community has come under scrutiny worldwide. This has severe implications in a country like India, which is a minority. It has always faced discrimination from the majority, the State, and its institutions. It has had an impact on the growth and development of the community in India.

Educational competence is crucial for the community to assert and stand independently. But the academic marginalisation of the Muslim population in India prevents this from happening.

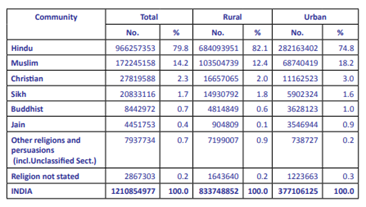

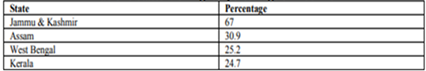

India is home to one of the world’s largest Muslim populations. “Muslims in India are about 17.22 Crores, i.e., 14.2 % of the total population of India follows Islam. India is home to close to 11% of the total Muslims Population of the World. While it claimed that India has more Muslims than Pakistan, it is not true statically. India has the third-highest Muslim population after Indonesia and Pakistan. Muslims make up the majority in UT Lakshadweep and Jammu & Kashmir while its population is actual states of Assam, West Bengal, Kerala, and Uttar Pradesh”[1]. Yet this community is primarily entrenched in poverty, illiteracy, political backwardness, and exploitation. Throughout history, there have been conflicts between the Hindu and Muslim minorities.

The socio-economic backwardness of the community is a disturbing factor. It has severe implications for where our country is heading. If this pattern continues, it could lead to unrest in society. If we don’t deal with it right now, we might reach a phase where we won’t know how to tackle it. The community needs to be empowered. They also face discrimination in many ways.

They are neither adequately represented in government services nor politics. So how are they to participate in nation-building? The first part of the paper deals with the socio-economic and political context of the Muslim community in India. Moreover, it tries to unravel the factors responsible for the community's backwardness. It covers the principal concerns of the community, education being one of the most significant ones. Education is an essential source of empowerment, especially for the deprived and marginalised communities. Afterwards, this paper contains the current educational situation of the community, the challenges in accessing education, the position of Muslim women and their educational status, how education is perceived within Islam and the history of schooling amongst Muslims in India. Furthermore, it looks at perceptions of madrasa education compared to regular instruction in the community. It looks at the politics in Urdu education and minority educational institutions. Lastly, it seems the role of NGOs as social capital in the academic development of the community.

Socio-economic Situation of the Muslim Community in India

“The concepts of majority[2] and minority[3] in the Indian context have a colonial history. The British had undertaken the Census to count and classify India’s population for administrative purposes. This set the notion of representation on numerical and religious grounds. This created a huge Hindu majority and several minorities, of which the most important was the Muslims. Thus began the number game and the voting behaviour of this minority became part of the symbolic politics. Issues linked to this are the politics of reproduction, the fertility rate of the Muslims and conversions” (Veer, 1994).

“As a minority in a largely Hindu nation, the most important concerns in the community are identity, security, and equity. Being identified as a Muslim in India is fraught with prejudice, bias, and stereotyping. The burqa, purdah, beard, and topi, which are a part of the identity of being a Muslim, are seen as signs of backwardness and fundamentalism” (Adil, 2019).

“The community is either ridiculed or looked at with suspicion. The men with a beard and topi are often picked up from public places for interrogation, while the burqa-clad women find it difficult to find a job and face impolite treatment in markets, hospitals, schools, public transport and so on. The media, too, has created this stereotypical image of Muslims. Their identity poses a hurdle when availing of housing or education for their children. It is often difficult for Muslims to avail of housing in non-Muslim neighbourhoods. The discriminatory attitude of educational institutions towards the community at the time of admission or availing of scholarships is also a serious issue”[4].

“Muslims are mostly found living in ghettos in India. This is mainly due to security reasons. After suffering during the communal riots, Muslims living in non-Muslim localities usually shift to Muslim-dominated areas” (Susewind, 2017). This has many repercussions. These ghettos become areas of neglect by the authorities. The ghettos are easy targets for negligence by municipal and government officials. Water, sanitation, electricity, schools, public health facilities, banking facilities, anganwadis, ration shops, roads and transport facilities are all inadequate in these areas. Muslim women are the worst sufferers as they are reluctant to go out of their ‘safe’ neighbourhoods to other sites to access these services. “The forced migration of Muslims from places where they lived for centuries also affects their employability and means of earning a livelihood. The shifting of ‘insecure’ Muslims to Muslim-dominated areas has boosted the demand for property in these areas. Consequently, property prices have shot up in such areas. In distress sales, the migrating Muslims sell their property at prices below the actual value”(A.T., 2019). But they pay higher prices to shift to the ghettos. Ghettoisation also prevents religious tolerance and socio-religious interaction with other communities.

Issues of equity that are most disturbing in the community are unemployment, representation, and poverty. “Muslims are mostly engaged in the unorganised sector. Displacement from their traditional occupations due to the competitive forces of liberalisation has had serious repercussions on the community” (Afroz, 2014). The traditional occupations of Muslims in industries such as silk and sericulture, hand and power looms, the leather industry, automobile repairing, and garment making have been badly affected by liberalisation. “Access to credit, which could help improve the community’s economic condition, is also inadequate. Private and public sector banks discriminate against Muslims in providing bank credit” (Nabiebu, 2019). In some states, many banks have designated Muslim-dominated areas as negative or red zones where they do not give loans. It is also difficult for Muslims to get a guarantee from a government official, which is required by the banks, due to the lack of Muslim presence amongst government officials. Nationalised banks hesitate to sanction loans under government-sponsored schemes to Muslims. Their lack of access to credit is further due to the absence of nationalised, private, and cooperative banks in Muslim-dominated areas.

The community representation in the government and private sector is quite dismal. Additionally, the discrimination faced by them at the time of seeking employment further keeps them away from development. Despite having the necessary qualifications, they are turned away from jobs due to their religious identity.

Table: 01 Religion-wise Population in India (Source: Socio-economic Caste Census, 2011)

Education and Muslims

The sense of insecurity in the Muslim community today is high. Issues of security, identity, poverty and the politics behind marginalising the community regarding employment and representation are vexing and burning issues. With the general deprivation in the community, the prejudice against them and the neglect by the state, education is an important aspect that could help empower the community.

Education plays a significant role in shaping the future of not only an individual but also a community as a whole. It influences the socioeconomic mobility of a community. It opens the door to many opportunities in life. It also makes a community aware of its rights. Hence the educational status of the Muslims in India today is essential to understand the historical context of education amongst Muslims and the perception of education in Islam. The general perception is that Muslims do not give importance to education. Most importantly, Islam commands the faithful to educate their daughters. Education is compulsory for every Muslim man and woman.

Muslims stress unrestricted access to sacred and secular knowledge, and acquiring it is obligatory for all. It ensures the upliftment of the lowly and the downtrodden, irrespective of sex and other backgrounds. It also believes in providing opportunities to develop its capabilities to the maximum.

“According to the Quran, the knowledgeable are genuinely God-fearing. Faith and knowledge are seen as inseparable. Human beings with knowledge are considered superior even to angels. The traditions of the Prophet also talk about acquiring knowledge as a religious duty. The Prophet is seen as a teacher, and Islam is the first religion to encourage universal literacy. Knowledge is not considered an end or a means for material gains in Islam. However, it is linked to spirituality. Knowledge should be acquired to understand the will of God, and one should live one’s life according to it to gain salvation. It stresses knowledge, which leads to righteousness and virtuous actions. Knowledge and practice are integrally linked. Hence education is inseparable from the training of the self” (Sikand, 2005).

Thus, there is an emphasis on the deep personal bond between the teacher and the student in a madrasa. The religious duty is to share knowledge freely, considered God’s gift. It follows the Quran, which calls for ‘commanding the good and forbidding the evil.’ It explains why so much investment was made in setting up madrasas to spread Islamic knowledge. Early Muslims were the proponents of science at a time when Europe plunged into the Dark Ages and the medieval Church put down scientists.

The general perception is that Muslims are opposed to education and would prefer to send their children to work rather than educate them. The other perception is that they like to send their children to a madrasa, which is the reason for their backwardness. Muslims argue that despite being educationally qualified, they are not employed in government services, and their representation is not proportionate to their population. Then what is the use of investing in higher education if they are discriminated against because of their religion? They face discrimination to a certain extent in the private sector too. Hence after getting some primary education, children must find some petty jobs to supplement the family income. Thus, the dropout rate among school-going children at all levels is considerably higher among Muslims than among other communities defined by religion.

In the educational status of the community, it is only natural to understand the challenges it faces in accessing education. There are internal and external factors that pose a hindrance to the same. Poor teaching quality and absentee teachers force children to take up private tuition, particularly for first-generation learners. The extra costs serve as a hindrance to education. The communal content of textbooks, as well as the school culture in some states, also acts as a hindrance. The complete absence of Muslim personages in books and the hostile environment in schools that discriminate cause concern.

Islam has, from its inception, placed a high premium on education and has enjoyed a long and rich intellectual tradition. Knowledge ('ilm) occupies a significant position within Islam, as evidenced by more than 800 references to it in Islam's most revered book, the Qur’an. The importance of education is repeatedly emphasised in the Quran with frequent injunctions, such as "God will exalt those of you who believe and those who know high degrees"[5].

“Arab society had enjoyed a rich oral tradition, but the Quran was considered the word of God and needed to be organically interacted with using reading and reciting its words. Hence, reading and writing to access the full blessings of the Quran was an aspiration for most Muslims”[6].

“Thus, education in Islam originated from a symbiotic relationship with religious instruction. Thus, in this way, Islamic education began. Pious and learned Muslims (mu’allim or mudarris), dedicated to making the teachings of the Quran more accessible to the Islamic community through Islamic school, taught the faithful what came to be known as the kuttab (plural, katatib)”[7].

Historians are uncertain when the katatib was first established. Still, with the widespread desire of the faithful to study the Quran, katatib could be found in virtually every part of the Islamic empire by the middle of the eighth century. The kuttab served a vital social function as the only vehicle for formal public instruction for primary-age children and continued so until Western models of education were introduced in the modern period.

“Even at present, it has exhibited remarkable durability and continues to be an important means of religious instruction in many Islamic countries. During the golden age of the Islamic empire (usually defined as a period between the tenth and thirteenth centuries), when western Europe was intellectually backward and stagnant, Islamic scholarship flourished with an impressive openness to the rational sciences, art, and even literature”[8].

In early Islamic history, monarchy prevailed in Muslim countries. A despotic monarchical system was not based on true Islamic ideals. A feudal class of nobles were the supporting pillar of the monarchy. However, Muslim scholars in medicine, anatomy, physiology, chemistry, physics, logic etc., were renowned. They learnt mathematics and astronomy from India and extended it further. Educating the masses did not receive state patronage. So it was up to the mosques, maktabs, madrasa, khanqahs and individual-centred schools to provide education with some assistance from the state.

“The rule of Muslim kings in India was not Islamic, and the state did not assume the responsibility of putting Islamic ideals into practice. This was necessary for their survival. But there was no universalisation of education. It was meant only for the refinement of the upper classes. During this period, the oppressed and the downtrodden flocked in huge numbers to Islam. The Muslim society was perhaps not prepared to receive them in such huge numbers even though they were not unwelcome. This is used as an argument when discussing the backwardness of the community. Some of the pre-Islamic values of ‘passivity’ and ‘predestination’ and ‘keeping to themselves’ remained with them. They were just content with their newly found social equality under Islam. Thus, they remained suppressed by the feudal class” (Siddiqui, 1984).

“The Educational backwardness of the Muslim community in India has been established and highlighted by several official reports such as the Gopal Singh Minority Panel Report, the reports of the 43rd Round and the 55th Round of the National Sample Survey, and the programme of action under the New Education Policy (1986) and NEP revised (1992) and Sachar (2006). The various schemes launched by the government to facilitate the economic and educational condition of Muslims have remained mostly on paper; the benefits of various government schemes aimed at improving the socio-economic condition of the weaker sections of society have not accrued to Muslims in any significant measure. Many schemes failed, but that should not deter us from continuing the endeavour”[9].

“Muslims are the largest minority in India; the majority of this community far behind concerns all material benefits, particularly in education and employment. There are many reasons for lower literacy among Muslims, but the main cause is the vision of Muslims toward modern education. It is observed that Muslims do not enthusiastically provide education to their children, especially their daughters. The educational backwardness of the Muslim community is generally attributed to their religious orthodoxy coupled with their emphasis on theological education with little effort to change the traditional education system and acquire the knowledge relevant to the needs of changing world” (Fahimuddin, 2004).

Indian Muslims are not having a positive attitude toward modern commercial education. Education is universally accepted as the most potent and effective tool to achieve any section of society. Although it is fitting that socio-economic condition also contributes significantly in this regard, a positive attitude toward education ensures the development of confidence and self-worth.

“Economic well-being can also be elevated naturally by the development of the level of education. Employment is also intricately linked with the status of education. Muslim students do not have access to quality education and thus end up with low-paid jobs and less remunerative employment. Muslims are not only the victims of poverty; rather have accepted inequality and discrimination as their inevitable fate. They also suffer from recurring insecurity because of a devastating episode of mass communal violence. Thus, they should take education as a matter of highest priority to improve their pathetic state of life. The majority of Muslims are leading life at the periphery of well-being. The benefits of mainstreams education are either not available to them or they, themselves, have decided to remain away from them, due to numerous reasons)” (Asma, 2015).

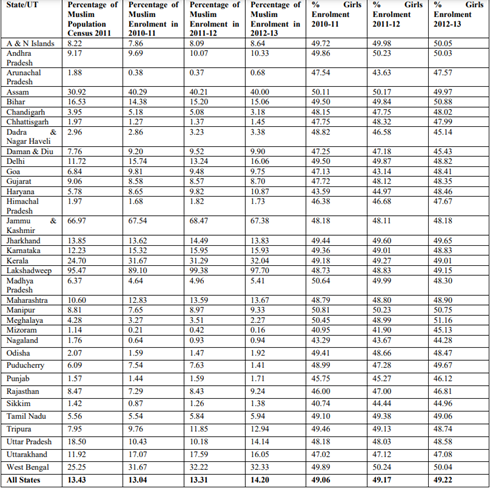

Muslims in India account for 13.43% population of the country, and the second largest denomination, after Hindus, who are 80.5%. About 35.7% of Muslims live in urban areas of India, and 36.92% of Muslims survive below the poverty line. The Sachar Committee was an eye opener as the problems were brought out, not in vague, but with the support of concrete facts and statistics. This report was probably the first attempt to analyse the conditions of the Muslim community using large-scale empirical data. It highlighted the relative deprivation of Muslims in India in various dimensions, including employment and education. Sachar Committee finds that school enrolment rates were among the lowest for Muslims but had improved recently. This is also consistent with the perception that the Community is increasingly looking at education to improve socioeconomic status.

“Sachar Committee Report (2006) confirmed that by most development indicators, the Muslim community is lagging other religious groups of India. Dropout rates are also highest among Muslims, which seem to increase significantly after middle school. Higher secondary attainment levels are also among the lowest for Muslims. The committee had identified poverty as the major barrier to education amongst Muslims as young children are expected to support their families rather than study. The maternal mortality rates and the incidence of underweight children and anaemic mothers are comparatively higher among Muslims. Their nutritional status in per capita calorie intake is also lower than the rest of the population. As we know, literacy is the first step in learning and knowledge building, and therefore, an essential indicator of human development” (Asma, 2015).

Table 02: States with the highest percentage of Muslims (Sources: Census 2011)

“As far as the identity of women is concerned, religion is depicted as gender unjust by the media. Deprivation of Muslim women is viewed as an issue typical of the community rather than a societal phenomenon. For many Muslim women, the home and community are the safest places in terms of physical protection and protection of identity. However, some Muslim women insist that given the opportunity to work and get educated, they would ‘manage’ all these issues” (Sachar, 2006).

“Education is an indispensable means for helping the Muslim women out of their economic misery because economic dependency is the major factor contributing to the low status of Muslim women. After independence, women’s education made considerable progress in India. The number of girls’ schools and colleges increased. Muslim girls going to schools and colleges also increased slowly but steadily. Muslim parents are becoming anxious to educate their daughters and sons” (Asma, 2015).

“The Sachar Committee Report (2006) also reflects the same feeling that parents feel education is not important for girls. Even if girls are enrolled, they are withdrawn early to marry them off. This leads to a higher dropout rate among Muslim girls. Muslim women are three times behind their Hindu sisters at the all-India level. Higher education attainment among girls is a rare phenomenon in urban areas. The studies done in the field of Muslim women revealed that the lack of good quality schools and hostel facilities for girls and poor quality of teachers are believed to be some of the important factors responsible for the low educational attainment among Muslim women. It is worthwhile to say that Muslim women have a strong desire and enthusiasm for education. Still, hurdles like low access to schools in the vicinity, poverty, financial constraints, and discrimination faced at school prevent them from continuing education” (Sachar, 2006).

“Determination is an element without which no person can succeed in any venture. Muslim women should create willpower or determination towards education to reach a peak elevation. Due to the influence of ancient traditions and practices in Muslim societies, especially in remote areas, women lose courage from childhood and become dependable on men; parents also discourage their female children from higher studies. Muslim women suffer more because they are not given enough freedom and hardly have access to higher education, though even primary education is not easily accessible. There is also a lack of schools and colleges in areas with a higher concentration of the Muslim population. Girls are enrolled in nearby schools and are not sent far off to study for safety reasons. Therefore, the Muslim women of the day need to develop their capabilities and make them more confident. These all demand a thorough discussion among policymakers, academicians and community leaders” (Asma, 2015).

“Over 75% of Muslim women in India are illiterate. In northern states, particularly the rural areas, 85% of Muslim women cannot read or write. In contrast, in the south, particularly in the urban areas, 88% of Muslim women are literate. Many factors for this educational backwardness include the state’s apathy toward their condition. The pathetic budgetary allocation for their education is proof of that. Other reasons are poverty, opposition to co-education after a certain level, shortage of girls’ schools and women teachers and early marriages. Although there is an increasing enthusiasm among parents to educate their daughters, they are concerned about preserving their cultural identity in the face of the religious onslaught and a widely-shared lack of confidence in being employed by the government” (Menon, 2006).

Table: 03) Percentage distributions of the Muslim population, Muslim enrolment, and Muslim girl’s enrolment in India, 2011-2013 (Source: DISE 2012-13; Flash Statistics

Identity vis-à-vis collective identities, NGOs, and Social Capital - An Integrated Approach to Educational Development

The idea of identity grew popular in the social sciences during the 1950s with the foundation of the concept by developmental psychologist Erik H. Erikson (1950), who studied how individuals emerged and built their identity through consecutive life stages adolescence, parenthood, etc. Identity consists of the conflux of the person’s self-chosen or ascribed engagements, personal characteristics, and beliefs about them (self); roles and positions in connection to significant others; and their association in social groups and sections (including both their status inside the group and the group’s status within the broader context. Hence this definition can be analysed by contents related to the study. Therefore, each type of content is attached to a specific process by which identities are formed among people who are not autonomous but can interconnect and interrelate.

“First, individual, or personal identity refers to the aspects of an individual’s self-definition, how s/he considers them (self) to be, and the qualities s/he gives to themself. These qualities are internalised ideas that can be goals, values, beliefs, standards for behaviour, self-esteem, and self-evaluation, among others. The process attached to individual identity content lies at the psychological level, and research usually emphasises the individual’s agency during the formation or the discovery of their identity” (V. L Vignoles, 2011).

In the Indian context, wherever the state and market have failed to reach, the NGOs have made their presence felt and tried to bridge the gap between the state and society. NGOs have become necessary instruments for social development. They are civil society organisations that build social capital. As we have seen that the state and market have failed to reach out to the Muslim community in India, the role played by the NGOs becomes pivotal to the development of the community. So, the research study now tries to understand NGOs as social capital and their part in the education of Muslims.

“Social capital is a broad term which subsumes the following; Relationships of trust, reciprocity and exchanges-This facilitate cooperation, reduce transaction costs and could provide safety nets for the poor; organisations with a common purpose- This implies membership of formal or informal groups in which adherence to mutually agreed or commonly accepted rules, norms and sanctions is a precondition and Networks and informal connectedness groups- This increases the ability to work together. The linkages that groups develop with other institutions/ groups and informal membership networks contribute further to their institutional capacity and strength” (DFID 1999).

“Coleman (1988) describes it as “productive potential‟ which derived from relationships between actors. A substantial number of studies have linked the role of social capital in economic development. As a resource embedded in relationships among people, it strengthens and facilitates cooperation, reciprocity, and risk-sharing in a collective form through norms, values, rules, and regulations. It stimulates economic growth and social development” (World Bank 1988, Putnam, 1993). “Two types of social capital are generally referred to: structured and cognitive social capital. Structured social capital refers to the roles, rules, procedures, and networks that facilitate information-sharing, collective action and decision-making through established roles”[10].

“Second one is social or relational identity refers to the many roles a social system assigns to the individual, such as the role of a child, spouse, co-worker, parent, or customer. Research on the process of social identity construction focuses on how social structures assign these roles and how they are secured and confirmed through social interaction. Finally, collective identity refers to people’s identification with a group or a social category. These groups and categories can be ethnicity, nationality, caste, religion, gender, families, work groups, NGOs, etc. the processes of collective identity formation look at interactions between individuals of the same collection to see how they communally construct collective identity definitions” (FIRER-BLAESS, 2016).

A significant division with social identities is that collective identity, as a vigorous construct, not only allows but also encourages collaborative action, which elucidates why collective identity is quickly initiated in NGOs. These three types of identity are rationally distinguished. Still, empirically they are intricately connected so that an indulgence of an individual’s identity goes throughout the study of all of them and their inter-relationships.

Polletta and Jasper (2001) state that the concept of collective identity is to respond to the following questions. First, it could shed light on why social capital developed. Resource mobilisation and political process assumptions could not explain why some issues were very mobilising in some countries. Still, not others, such as manual scavenging, are an intense topic of mobilisation in India but neither in the United States nor Europe. The second issue concerned how NGOs choose their organisation and tactics, which were seldom in disagreement with what should have been the behaviour of a rational actor. They could describe defining characteristics as more critical to sustaining than contributory factors. “The third question referred to the cultural effects of NGOs, i.e., how NGOs changed the collective identity of a given group and its reception by the outside. The last question concerned why individuals were joining NGOs in the first place” (FIRER-BLAESS, 2016). Hence NGOs can be defined as a group to accomplish which is deterred from struggling against common problems/situations with collective action.

“Melucci defines NGOs by the fact that it performs activist types of collective action. An activist action is conflictual, system-breaching, and showing solidarity. It attempts to bring social change through conflict against an actor with specified resources at stake. It does so through actions in which participants know they act as a group”[11].

Hence it is applicable for this paper because it is connected to NGOs related to the advancement of a specific population, social identity, lifestyle, and educational development of Muslims.

With the government’s apathy towards the Muslims, efforts within the community to build social capital and redress the situation are being made. Any financial assistance extended by a philanthropic institution within the community can play a significant role in overcoming the obstacles to accessing education. The grass-root level institutions could have a positive impact in shaping the lives of many children. The dropout rate could reduce with this kind of help. There has been a considerable amount of contribution, on the part of many NGOs, in promoting education among Muslim boys and girls. The community’s tradition of ‘Zakaat’ is used to fund education. Specifically, the research tries to understand the role played by a Muslim NGO in promoting education. A Muslim NGO, here is meant a registered NGO established by Muslims and working for the welfare and upliftment of Muslims.

There are many Muslim NGOs in the country, and groups of Muslims have formed educated or uneducated, professionally trained, or unskilled, innovative, traditional, visionary, or humble to work for the poor and marginalised in the community.

“There are Muslim NGOs in every field - economic, social, educational, cultural, medical, socio-religious, socio-political, scientific, technological etc. There are many challenges which NGOs have to face. There is scope for improvement in terms of their vision, structure, resource base, work strategies, priorities, link with national welfare schemes and performance etc. Then there are issues of human and material resources, their optimum use, regional imbalances in the geography of NGOs, absence of a standard measure and practice to check performance, lack of inter and intra-organizational networking and cooperation, deficiency in professional skill and approach, lack of knowledge of relevant government laws and financial schemes, etc.”[12].

Despite these limitations, their contribution is worth mentioning. There are Muslim NGOs, which are promoting education through sponsorship or scholarships among the poor students in the community. “Many Muslim NGOs raise funds from within the community through ‘Zakaat.’ Zakaat is a compulsory charity that the faithful followers must pay for yearly. It means an increase. It is one of the five pillars of Islam. It is associated with surplus money or asset. Muslims must pay Zakaat as a specified portion of their accumulated earnings or wealth over one year. It is believed that ‘Zakaat is not a donation but due of Allah Almighty vis-à-vis the poor.’ It has the following objectives: a) Right of Allah b) Purification of self and wealth c) Social security to the poor of society”[13].

Conclusion

“The above discussion on the educational vision of Muslims concluded that Muslims were far behind the other communities previously, however in the present governance their situation is changed. Their vision toward education is still traditional. However, Religion-based discernment is decreased only because Muslims get engrossed in value family-based occupations which are enhanced by Skill India’s mission wherein they face less competition. Hence now Muslims record low discrimination in admittance to employment and wages. This simply shows that Muslims have certain professional skills acquired through family and peer groups, in repair/maintenance, carpentry, construction etc. which are polished and professionalized with the help of partner NGOs imparted by the present government self-employment and skill development schemes through technical education. However, previously they do not want to accept modern education because they suffer socially, economically, and politically but self-employment through skill development removed their hindrances. They do not want to give higher education to their daughters due to many reasons; at present, somehow, they are now coming up for education and improving day by day for the last two decades and are learning to stand on their own feet; they still, this effort will change the situation. Muslims have a lower share in Professional education, especially in the management sector. Thus, there is a need to change the vision of Muslims from traditional to modern education. There is also meagre study on Muslim’s educational condition; it is the duty of social Anthropologists and Sociologists to find out the educational status and to analyse the state of education among the Muslims of various parts of the country to explore the constraints of educational upliftment among them” (Asma, 2015).

It is the need of the hour that Government should move on and do something for the development of Muslims. When the state cannot reach out to minorities, it is natural for the community to take initiatives to bring about growth in the community. These initiatives and their impact on the community need to be delved into. These philanthropic initiatives can help build social capital and foster change. Hence the paper has interlinked the role of NGOs in the development of education in the Muslim community and the kind of stand they take with the help of State Institutions.

References:

A.T., A. K. (2019). Forced Migration of Muslims from Kerala to Gulf Countries. In S. I. Saxena, India's Low-Skilled Migration to the Middle East. (pp. 207-222). Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan.

Adil, Y. (2019, October 16). FII-INTERSECTIONAL FEMINISM DESI STYLE/Looking Beyond The Stereotypes: Muslim Women In India. Retrieved April 22, 2020, from https://feminisminindia.com: https://feminisminindia.com/2019/10/16/looking-beyond-stereotypes-muslim-women-india/.

Afroz, I. (2014, December 15). Economic Challenges Before India’s Muslims. Market Express – India’s First Global Insights & Analysis Sharing Platform. Mumbai: Market Express.

Asma, T. S. (2015). Educational Vision of Muslims in India: Problems and Concerns. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Invention, 4 (3), 21-27.

Fahimuddin. (2004). Modernization of Muslim Education in India (Vol. 1). Delhi, Delhi, India: Adhyayan Publishers & Distributors.

Menon, Z. H. (2006). Unequal Citizens: A Study of Muslim Women in India. New Delhi, India: Oxford University Press (Oxford India Paperbacks).

Nabiebu, M. &, Takim Otu, M. (2019). The Legal Conundrum of Non-Interest Banking. A Case Study of Islamic Bank In Nigeria. International Journal of Scientific Research and Management, 7 (7), 141-52.

Sachar, R. (2006). Social, Economic and Educational Status of the Muslim Community of India-A Report. New Delhi: Cirrus Graphics Pvt. Ltd.

Siddiqui, M. (1984). Educating a Backward Minority. Calcutta: Abadi Publication.

Sikand, Y. (2005). Bastions of The Believers: Madrasas and Islamic Education in India. London, U.K.

Susewind, R. (2017). Muslims in Indian cities: Degrees of segregation and the elusive ghetto. Environment and Planning A, 49 (6), 1286-1307.

V. L Vignoles, S. J. (2011). Introduction: Toward an integrative view of identity. In V. L. Vignoles, Handbook of identity theory and research (pp. 1-27). New York, NY: Springer Science & Business Media.

Veer, P. v. (1994). Religious Nationalism: Hindus and Muslims in India. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Author´s

Address:

Vikram Singh

Associate Professor Department of Social Work, Regional Campus Manipur Indira

Gandhi National Tribal University, Amarkantak Madhya Pradesh, India

+91-9863664584

vsvikkysingh@gmail.com