Collaborating or Colluding: A Practice Research Project with Ex-Offenders and their Families in Singapore

1

Ex-offenders’ reintegration into the community is arguably one of the most challenging contemporary issues, with policymakers calling for more effective coordination between criminal justice and social service agencies (Bond, 2010). Through a small scale practice research project, a group of practitioners and academics collaborated to work with the ex-offenders and their families. This experience illustrated how a collaborative effort can benefit those involved, including the academics, the practitioners, the clients, and the development of the offender rehabilitation service in Singapore. It has also challenged the often exaggerated gulf between the roles of researchers and practitioners (Lepper & Harris, 2006; McLeod, 2003).

This paper documents the specific lessons learned in working with the ex-offenders and their family members from engagement, assessment, intervention and termination, using the family system perspective. It considers the key dilemmas and challenges the practitioners and academics encountered in serving the ex-offenders and their family members, as well as the impact this practice research project made in changing related larger systems.

2 Objective of the practice research project

With the aim to serve the ex-offenders and their family members, this practice research project, supported and funded by the Association of Social Workers in Singapore, operated for 22 months from May 2006 to March 2008. This project specifically aimed to work with 3 cases intensively from engagement to termination, carefully documented the pertinent issues, relevant measure and tools used, skills and techniques for each stage of work. Three social workers participated in this project, each introducing an ex-offender’s case they are responsible for. They were from 3 different social service agencies serving ex-offenders (namely Singapore Aftercare Association, Fei Yue Family Resource Centre, and Fei Yue Family Service Centre [Chua Chu Kang]). As the project consultant, I worked closely with each social worker, the individual ex-offenders and their families from engagement (about two months before released from Singapore Prison Service [SPS]) to termination (approximately 6 months after release from SPS). The worker concerned and I would visit the client and their family members at the locations convenient for them, other than inviting them to the agencies when necessary. This included the prison, their home or any other locations deemed appropriate (e.g., community centre). All sessions, wherever they were conducted, were audio taped or videotaped with the informed consent of the clients. In addition, I invited another social work professor from the Department of Social Work at the University of Singapore, who is an expert in the area of service evaluation among her other expertise, to help in designing and documenting the work that we carried out with the ex-offenders and their family members.

The project had several distinct characteristics: it actively involved the ex-offenders’ families, multiple organizations, and focused on culture sensitivity, and systematic recording using the practice research principles and traditions (http://www.socsci.soton.ac.uk/spring/salisbury/). Specifically, the practitioner-researcher collaboration of this project has exemplified the possibility of narrowing the gap between practice and research, in that the researcher has acted as a consultant who participated in the practice actively, rather than simply supplying the practitioners with the technical expertise and awareness of the literature to carry out the project (McLeod, 2003). Conversely, the front-line practitioners also actively participated in the documenting and discussion of the project from the start. Most importantly, the practitioners and the academics consciously engaged the clients in reviewing the findings of this study, and sensitively involved them to provide feedback to the policy makers through the videotaped family sessions and documentation process. In many ways, we concur with the argument of Lepper and Harris (2006) that what researchers do is not vastly different from what practitioners do, or what we all do in relating to the world and one another. We see our research process as “a way of slowing down observation of process of relating through the use of a variety of methods, so that we can discover more deliberately and consciously what is happening” (p. 55).

3 Referral Sources and Case Selection Criteria

The project focused on ex-offenders referred to the Case Management Framework or the Reformative Training Centres administered by the Singapore Prison Service, or any other referral with a focus on offender rehabilitation.

The project team agreed that ‘cases’ would be selected based on four criteria: (a) ex-offenders who explicitly indicate a desire to improve family relationships as a goal, (b) ex-offenders’ family members who are willing to be engaged in treatment, (c) ex-offenders and family members consent to take part in the research process, involving videotaping, and (d) ex-offenders and family members who are willing to travel to our office for family meetings, where necessary. Gender, age, ethnicity of the clients and family members would not be controlled.

Eventually, we were privileged to work with three ex-offenders; their personal data are presented briefly in Table 1:

Table 1

Basic information of the three ex-offenders

|

Ex-Offender |

Age |

Sex |

Ethnicity |

Previous Offence |

|

Case 1 |

19 |

Male |

Chinese |

Robbery |

|

Case 2 |

21 |

Male |

Chinese |

Caused grievous harm to others and drug abuse |

|

Case 3 |

33 |

Male |

Malay |

Drug trafficking |

Informed consent was sought from the ex-offenders before their release from prison. Details about the project goals, process [including video and audio recording], their rights, and the involvement of their family members were highlighted. When we met with their family members, informed consent was separately obtained.

4 Study design and measures

Single case evaluation design (Dallos & Arlene, 2005; Royse, 2004; Yin, 2009) was adopted to carefully monitor the process and outcome of each case. Based on the logic of time-series designs, we used repeated measures obtained during our initial meetings with the ex-offenders before discharge from prison, and repeated the measures during and after intervention to see if patterns sustain. Some of the advantages of using single case evaluation design include obtaining immediate, inexpensive, and practical feedback, and helpful in monitoring the ex-offenders’ progress (or lack of it) systematically. Dallos and Arlene (2005) maintained that single case studies can be adapted to produce research that explores meaning and experience and is reflective, collaborative and do-able, and allows a consideration of the client’s experience in the wider contexts of their relationship, community and cultural location. They encouraged collaborative case study research that incorporate the perspectives of clients, family members and other people involved in the process. By adopting single case evaluation, we hoped to find a “do-able” form of research, which is familiar to the practitioners. What the practitioners needed to do differently in this project included documenting greater details, collecting evidence [e.g., use of different tools, careful analysis of videotaped sessions] and using alternative explanations of the evidence in a more systematic way. By so doing, we aimed to be more than descriptive and explain what we have found. This is possible since we carefully followed through in detail the complexity of the ex-offenders’ situation and the unfolding events using the single case design (Yin, 2009).

Three measurements were used to assess the family relationships of the ex-offenders. First, the repertory grid (Kelly, 1955; Houston, 1998), an interactive and case-study perspective, was used to assess the changes of the ex-offenders’ perception of family relationships at pre- and post-treatment, and to evaluate individual changes, if any. The repertory grid is a simple, but powerful, rating-scale which uses the individual’s own constructs as the subject matter, and arrives at a precise description uncontaminated by the interviewer’s own views. The “elements” we used included “Self now”, “Self before arrest”, “Ideal self”, “Self seen by others”, and 6 to 7 family members (e.g., father, mother, sister, nephew etc) the ex-offenders deemed significant to them. I was responsible in conducting the interview to elicit the constructs, rating the grid, and conducting the analysis immediately after administering the repertory grid, which included the salience of the elements, principal component analysis, and constructing the grid using the computer analysis package GridLab (Walter, 2002).

Second, the Self-Report Family Inventory (SFI) was administered at pre- and post-treatment to assess family changes. SFI is a 36-item scale that assesses family functioning (Beavers and Hampson, 1990). The scale yields five dimensions of family functioning that include (a) family health, (b) conflict, (c) cohesion, (d) directive leadership, and (e) expressiveness. I was responsible in administering the SFI with the ex-offenders and their family members at the first and last session.

Finally, the Timberlawn Couple and Family Evaluation scales (TCFES) (Lewis et al. 1999) were chosen to chart the changes of the family systems of those undergoing family-based interventions immediately after each family session, so as to obtain a more in-depth understanding of the salient aspects of family relationship in offender rehabilitation. Each social worker concerned and I would score the TCFES conjointly after each session. Where there was disagreement, we would discuss and agree on a score.

I conducted a full day training session for the social workers to learn about the above measures. Interestingly, when the workers started to use the tools more, they became more comfortable with them. Gradually, these tools were used not for research purpose only. They were also used for understanding, guiding and planning our practice with each case. They provided useful frameworks for us to think and discuss each session with reference to specific dimensions of each tool, which we could sometimes check back with the ex-offenders and their family members. In this sense, the tools were helpful beyond their research purpose in that they also provided an opportunity to for us to discuss and examine our practice in each case.

5 Intervention

The overall goal of our intervention was to improve family relationships so that the family can become a support for the ex-offenders’ rehabilitation. We drew heavily from the Structural Family Therapy theory (Minuchin, 1974; Minuchin et al. 2007). The format of treatment also took reference from the Multidimensional Family Therapy model (Liddle, 2002; Liddle, et al. 2010), which has its roots in the structural-strategic family therapy tradition. One aspect of multidimensionality in assessment and intervention is its inclusion of extra-familial factors in maintaining and treating problems. These include peer, educational, and legal and justice system, in addition to individual and family domains.

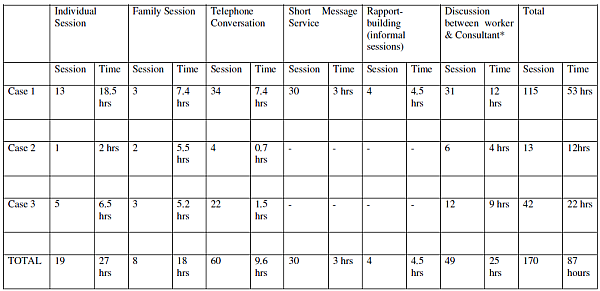

We met each ex-offender after he indicated the desire for us to work with his family. Before discharge, we would meet with the ex-offender’s family members, either in the agency or at their home, to discuss their expectations of the ex-offenders upon discharge, and to discuss the practical arrangements for the ex-offender’s release. After their release from the prison, we continued to meet with the individual ex-offenders and their families over a period of 6 months. In total, the team spent approximately 71 hours working on three cases that included 159 sessions, as reflected in Table 2 (see below). It is note worthy that the practitioners and the consultant spent substantial amount [i.e., at least 49 sessions using approximately 25 hours, which is equivalent to 28% of the total time spent for the project] on discussion. This entailed communication via electronic mails, telephone, and meeting as a

Table 2

Summary of Time Spent with the 3 Cases on Interviews, Contacts with Clients, Discussion and Others

*Discussion between worker & consultant included electronic-mail and phone discussions, reporting, updating and decision–making, as well as analysing and consolidating the findings of the project.

sub-team on respective cases between individual practitioner and me as the consultant. In addition, the three practitioners and I would meet occasionally to discuss as a team, and update each other about the cases. This intensive collaboration with the practitioners required significant time and energy from them, particularly as they also had to contend with their regular workload which was already heavy. With hindsight, we could have negotiated for their agency to provide more concrete support, such as time-off or reduction of other duties for their participation in this practice research project. Despite the additional demand, the practitioners conscientiously and diligently worked on this project as they felt that the process of working together would help their professional development. This is particularly because they were interested in working with the family members of ex-offenders, an area they had deemed important but did not feel confident enough to embark on earlier.

6 Roles and Responsibilities in Integrating Practice, Research and Policy

The social workers assumed all the responsibility in managing and coordinating the case, provided support and feedback to me as the project Consultant, and reported to their respective organisation’s management accordingly. The social workers were expected to be ‘the contact person’ if crises or emergencies arose. My role as the consultant included providing research input, as well as clinical consultation to the case worker and working directly with the client and their family members from the start. In many sense, the workers took a lead in this practice research project for what needed to be done for the ex-offenders and their family members. They have accumulated extensive experience in working with the ex-offenders as well as the other stake holders, such as the Singapore Prison Service and the other professional organizations. This is important as offenders have a myriad of economic, social, physical, and mental health needs that require services from several social service providers and public agencies (Bond, 2010). As the consultant I had to defer to them according to their respective agencies’ policy and practice. But at the same time, my role as a consultant also included the need to guard against the assumption that practitioners can or should speak on behalf of service users. Alongside this I had to be wary of the social workers assuming that I, as the consultant, would necessarily know how to act in empowering ways with the ex-offenders and their family members or would have this as a priority (Fisher, 2002). The role of a consultant can be constrained by “the elites who can pay to have their concerns addressed” (Huang, 2010, p. 95). However, I actively stretched my role as a consultant and actively engaged the practitioners in the process of working with the ex-offenders, and documenting our experience.

In this project, we consider research as a widely applied instrument for harnessing knowledge and providing insight into complex processes of working with ex-offenders and their family members. We also believe that research helps in generating more options for policy, management, and service improvement and in empowering people and organizations. In other words, we consciously ensured that this project was based on mutual interest, trust, understanding, sharing of experiences, and a two-way learning process with the key stakeholders (Maselli et al. 2004). Once we received financial support from the Singapore Association of Social Workers, we forwarded our proposal to the Singapore Prison Service and sought their approval and support for this project. We were not disappointed, and were impressed by the openness and support rendered by the authority. In this case, we were able to garner support, and make this a project that is beneficial not only for the ex-offenders and their family members, but one that would help the field to develop better service.

As systematic assessment of the ex-offenders’ families was a new dimension of practice for the social workers. I, as the consultant, began by providing the assessment tools to them and engaged them to actively use these tools. One challenge I had was helping the practitioners to see the value of using these tools to systematically document our work. Another challenge was reducing their apprehension about using the tools. However, the excitement of the workers in formulating and assessing the cases from a different perspective eventually outweighed the challenges we faced initially. I found it most rewarding when the social workers and I could work in partnership to generate hypotheses and questions for each case. This allowed us to plan for cycles of action and reflection. We became more reflexive about our practice with the ex-offenders and their family members, which continually unfolded. Based on the experience of carrying out this practice research project, we are of the persuasion that it is important to include the contexts and family systems when assessing the individuals, and important to incorporate different individuals’ perspective in assessing the family.

The development of each case was carefully charted and documented by both the social worker and I (the consultant) respectively. The social workers and I made our own case notes after each session, and exchanged and discussed our observations and assessments periodically. We would review the audio-taped or video-taped sessions regularly. The videotaped and audio taped sessions were transcribed eventually by research assistants, and analysed with the aid of a computer assisted analysis package NVivo (Version 2). Cases discussion sessions before and after each session were conducted, with notes taken to record the key points made. When we concluded our work with the ex-offenders and their family members, we followed up with the cases two to three months after the termination.

In addition, the social workers and the academics conducted four 4-hour sessions [i.e., approximately 16 hours] to discuss and crystallize the experience of working with the ex-offenders and their family members from engagement to termination. One of the ex-offenders was invited to conduct a participant-review of our findings. Based on these findings, a workshop was conducted for the management of key service providers, that include the Singapore Prison Service, the Singapore Corporation of Rehabilitative Enterprises, The Ministry of Community Development [Rehabilitation, Protection and Residential Services Division], National Council of Social Service, the Community Development Councils which were responsible for providing financial assistance to ex-offenders, and the managerial figures of the social service organisations reaching out to ex-offenders. We will highlight the outcomes of this workshop in the next section.

As a consultant to the project, one of my paramount concerns was to ensure that the project was useful to the ex-offenders and their family members, the practitioners as well as the other stakeholders such as the Singapore Prison Service. Huang (2010) has suggested that quality of action research (1) proceeds from a praxis of participation, (2) is guided by practitioners’ concern for practicality, (3) is inclusive of stakeholders’ ways of knowing, (4) helps to build capacity for ongoing change efforts, and (5) engages with those issues people might consider significant for ‘the flourishing of people, their communities and the broader ecology’. Such a guide for quality work is demanding. Working with the ex-offenders and their families was time consuming and daunting, as we were confronted with a range of issues from the individual ex-offenders, as well as their family members. Since all three social workers were not used to working with family members of the ex-offenders before their release, it was intriguing for them to have to deal with additional information and perspectives provided by the family members. As a consultant, I found it important to provide support to the practitioners by jointly planning each family session carefully, and encouraging them to take on new challenges in meeting the family members. Perhaps, one of the most rewarding experiences for us was communicating the experience and findings of our project as a team. Apart from the stereotypic form of a journal article [such as this], several academic conference reports that we presented, we are glad that we were able to reach a more diverse set of audiences than most other types of research, including academic colleagues, policy makers, practitioners, community leaders and funders of our project through organizing a workshop. This is particularly meaningful for us because we were able to bring to bear the emancipatory value of this practice project (Dallos & Vetere, 2005). We were able to give voice to the thoughts and experiences of the ex-offenders and their family members and present them to policy makers, thereby effecting changes to the larger system.

7 Dialoguing with the Policy Makers

After consolidating our learning from working with the ex-offenders and their families, we decided that the findings could be useful feedback to the stakeholders and decision makers. A full day workshop was organized for this group which involved a total of 16 participants: the Deputy Director/Chief of Staff of the Singapore Prison Service; a senior officer from prison counselling service; two Assistant Directors, and two managers from the probation service of Rehabilitation, Protection and Residential Services of the Community Development, Sports and Youth; the Assistant Director of the Service Development Division of the National Council of Social Service; 4 senior members of the Community Development Council (which provides financial assistance to ex-offenders); and 5 executive directors of social service agencies related to serving ex-offenders. The workshop presented what we did, as well as the key issues and challenges of each stage of work, often augmented with the case materials, video and audiotape materials, and reflections that we have consolidated. The participants were organised into small groups of 4 to 5 persons, and were invited to participate in a total of seven discussion sessions, mostly focused on policy related issues (See Appendix A for the discussion guide). We raised some unnerving issues during the workshop such as the inherent risks of group reporting for urine analysis, the prison officers’ continual struggle between care and control, and the gaps in collaboration between the criminal justice and the social service sector. We were glad that participants actively participated in discussing and debating, and unanimously agreed that there should be more collaboration. Given that there were unpredictable differences between individual offenders, and differences in the families and communities to which they are returning, the process is characterized by uncertainty (Bond, 2010). Offender reintegration also operates under time constraints given that offenders must access services across numerous organizations soon after release or face increasing risks of recidivating (Petersilia, 2000). Collaboration is therefore expected to be an effective mechanism for addressing these pressures (Clairborne & Lawson, 2005).

The workshop was well received. The following comments were made when participants were asked “What did you like best about this workshop?”:

-

Very informative, sharing of different skills and best practices

-

Reflective

-

Like the panel discussion portion as it is very interactive. Brainstorming ideas to map clients better.

-

One of the very fruitful workshops that I have attended.

-

Individual and Family Assessment.

-

Intervention traps

-

Clearly spell out issues involved in engagement and assessment, such as the use of repertory grid.

Such a platform for dialogue and exchange promoted a partnership has allowed all involved to have a voice in decision-making processes, so that better services could be provided for the ex-offenders and their families. Bond (2010) has noted the challenges of collaboration between the various agencies and those involved helping ex-offenders to re-enter the community, they include limited resources, conflicting beliefs, confidentiality concerns, issues of territoriality, conflicting goals, lack of trust, differences in perceived status, differences in decision-making styles and performance assessment. In the face of such a plethora of difficulties, we must not assume that practice research with ex-offenders and their families is easy. Despite these difficulties, we envisage that practice research can be a widely applied instrument for harnessing knowledge and providing insight into complex issues, establishing interconnected and supportive relationships in which trust can be built, and can help in generating options for policy, management, and action, and in empowering people and organizations (Bond, 2010; Maselli, Lys & Schmid, 2004).

8 Epilogue

The drive for social work practice to be effective in the face of limited resources needs little exposition. Inevitably, this means that social workers need to find a way of delivering the results. But as noted by a group of interested social work professionals that came together, organised by SPRING – the Southampton Practice Research Initiative Network Group) in Salisbury in the United Kingdom, there needs to be a continual dialogue between academics and practitioners (SPRING, nd):

A major problem is a mainstream assumption that research leads practice.

But research also needs to be practice-minded in order to better study and

develop knowledge which emerges directly from the complex practices

themselves. Practice research, involving equal dialogue between the worlds

of practice and research is important as a concept, since it seeks to develop

our understanding of the best ways to research this complexity.

This practice research project, albeit a small scale study, aimed to serve the ex-offenders and their families, demonstrated that collaboration between practitioners and academics is not only possible (Sim & Ng, 2008), but fun and fulfilling. Most importantly, we are glad that the ex-offenders and their families have also taught us many lessons. They have made an impact in our society. As Gambrill (2006) ended her seminal book on “Social Work practice: A critical thinker’s guide”, we concur that:

The quality of becoming rather than of being characterizes a professional. This requires a commitment to enhance and maintain values, knowledge, and skills that maximize the likelihood of increasing the personal welfare of clients and avoiding harm. Responding to mistakes as learning opportunities and recognizing the limits of your ability to help as well as the uncertainty involved in everyday practice will help you to avoid the dissatisfaction and negative emotional reactions reflected in burnout. (p. 735)

A way forward to develop services for ex-offenders and their families in Singapore is through collaboration between practitioners, academics, and the justice systems. This collaboration ought to, as has been the case elsewhere (e.g., Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health, 2008; Serrano-Aguilar et al., 2009), actively involve the service users, that is the ex-offenders themselves in developing the practice research.

9 Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the Singapore Association of Social Workers, the Mavis KHOO Fund, Singapore Aftercare Association, Fei Yue Family Resource Centre, and Fei Yue Family Service Centre [Chua Chu Kang], and the Singapore Prison Service, for their support to this groundbreaking practice research project in Singapore. A special note of thanks is due to Dr. NG Guat Tin, who has provided insightful input to our project. My heartfelt gratitude must go to Miss Priya ARUL, Miss Winnie CHNG, Mr. Tony ONG for walking this journey with me. Above all, I am not able to find appropriate words to express my appreciation and respect to the three ex-offenders and their family members: Without your participation, we would not have been able to create the knowledge that you have taught us.

10 Appendix A

Workshop Discussion Guide

Discussion 1: Engagement

What are the implications for practice and policy for using less conventional methods to engage the ex-offenders?

Discussion 2: Engagement

a. What are the dilemmas of splitting up the care and control roles in ex-offenders rehabilitation service?

b. Is there sufficient coordination between in-care and after-care service currently?

Discussion 3: Assessment

What is your assessment based on the above Repertory Grid before the ex-offender is released from Prison?

a. What are his strengths?

b. What are his weaknesses?

c. What is his relationship network like?

d. What would be your concern in working with this case, based on the grid?

Discussion 4: What would you do with the following scenario?

The ex-offender, aged 19, had sex with his 15 year-old girlfriend two weeks ago. She is now pregnant. The ex-offender called in panic to let you know that his girlfriend wants to abort the baby. But he would like to keep the baby. In addition, you found out that the girlfriend had actually run away from the Girls’ Home about 6 months ago and has been under a warrant of arrest. She spends her nights in a void-deck as she is not talking with her parents who sent her to the Home. Discuss in groups of threes:

a. What are the issues at hand?

b. What further information do you need?

c. What would be your plan of actions? Please state clearly the rationale or theoretical framework for your action plans.

Discussion 5: To give or not to give?

a. How many times of providing financial assistance is one time too many? (e.g., Social Service Organisation A provides financial assistance for 1st job only, with a four weeks duration)

b. What are the criteria for providing financial assistance (e.g., Community Development Councils do not provide financial assistance to individuals who live in 4-/ 5-room flat/private property)?

c. When should financial assistance stop if the income of the ex-offender is not stable after 3 months due to change of jobs and family financial difficulty?

Discussion 6:

a. What are the practice and resource implications for the practical help rendered to ex-offenders (e.g., outreach, networking, and case management)?

Discussion 7:

a. Highlight one thing you have personally learnt in attending this one-day workshop that pertains to:

o working with the ex-offenders, and/or

o working with the family members of ex-offenders

Reference

Beavers, W. R., & Hampson, R. B. 1990: Successful families: Assessment and intervention. New York: Norton.

Bond, B. J., Gittell, J. H. 2010: Cross-agency coordination of offender reentry: Testing collaboration outcomes. Journal of Criminal Justice, 38, 118–129

Clairborne, N., & Lawson, H. A. 2005: An intervention framework for collaboration. Families in Society: The Journal of Contemporary Social Services, 86, 1−11.

Dallos, R., & Vetere, A. 2005: Researching psychotherapy and counselling. New York: Open University Press.

Fisher, M. 2002: The role of service users in problem formulation and technical aspects of social research. Social Work Education, 21(3), 305 -312.

Gambrill, E. 2006: Social work practice: A critical thinker’s guide (2nd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Houston, J. 1998: Making sense with offenders: personal constructs, therapy and change. New York: Wiley.

Huang, H. B. 2010: What is good action research? Why the resurgent interest? Action Research, 8(1), 93–109.

Kelly, G. The psychology of personal constructs. New York: Norton.

Lepper, G., & Harris, T. 2006: Towards a collaborative approach to clinical psychotherapy research. In D. Loewenthal & D. Winter (Eds.) What is psychotherapeutic research (pp. 53-59). London: Karnac.

Lewis, J. M., Gossett, J. T., Housson, M. M., & Owen, M. T. 1999: Timberlawn couple and family evaluation scales. Dallas: Timberlawn Psychiatric Research Foundation.

Liddle, H. A. 2002: Multidimensional family therapy for adolescent cannabis users, Cannabis Youth Treatment Series, Volume 5. DHHS Pub. No. 02-3660 Rockville, MD: Center for Substance Abuse Treatment, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services).

Liddle, H. A., Dakof, G. G., Henderson, C., Rowe, C. 2010: Implementation outcomes of Multidimensional family therapy – Detention to Community: A reintegration program for drug-using juvenile detainees. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, XX(X) 1–18.

Maseli, D., Lys, J. A., & Schmid, J. 2004: Improving Impacts of Research Partnerships. Switzerland: Swiss Commission for Research Partnerships with Developing Countries, KFPE.

McLeod, J. 2003: Doing Counselling research (2nd ed.). London: Sage.

Minuchin, S. 1974: Families and family therapy. Cambridge, M. A.: Harvard University Press.

Minuchin, S., Nichols, P. M., & Lee, W. Y. 2007: Assessing families and couples: From symptom to system. Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Nichols, M. P. 2010: Family therapy: Concepts and methods (9th ed.). Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Petersilia, J. 2000: When prisoners return to the community: Political, economic and social consequences. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice.

Royse, D. 2004: Research methods in social work. Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/Cole

Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health 2008: A review of service user involvement in prison mental health research. London: Author.

SPRING. [n.d.] The Salisbury Statement on Practice Research. Available from South Hampton University, SPRING [Southampton Practice Research Initiative Network Group]. http://www.socsci.soton.ac.uk/spring/salisbury/

Serrano-Aguilar, P., Trujillo-Martin, M. M., Ramos-Goni, J. M., Mahtani-Chugani, V., Perestelo-Perez, L., & Posada-de la Paz, M. 2009: Patient involvement in health research: A contribution to a systematic review on the effectiveness of treatments for degenerative ataxias. Social Science & Medicine, 69, 920–925.

Sim, T., & Ng, G. T. 2008: Black cat, white cat: A pragmatic and collaborative approach to evidence-based social work in China. China Journal of Social Work, 1(1), 50-62.

Walter, O. B. 2002: GridLab for Windows 95/98/NT. Berlin: Medical School of Humboldt University Berlin.

Yin, R. K. 2009: Case study research: Design and methods (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Author´s Address:

Timothy Sim, PhD

Assistant Professor

The Hong Kong Polytechnic University

Department of Applied Social Sciences

Kowloon

Hong Kong

Tel: ++852-2766 5015

Fax: ++852-2773 6558

Email: timothysim@yahoo.com.sg

urn:nbn:de:0009-11-29843