Implementing Swedish Models of Social Work in a Russian Context

1 Introduction

The economic and social changes taking place in Russia in recent decades have implied a restructuring of the Russian society. Among other things, Russian leaders have expressed a need for the reorientation of social development. In the 1990’s, cooperation was initiated on a number of social work and social welfare projects with international support, a process further speeded up during President Jeltsin’s state visit to Sweden in 1997. Discussions between the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida) and the Russian authorities dealing with welfare issues started from the assumption that Russian professional social work was weak and needed to be strengthened. In the 1990's Sida was also given a stronger general mandate to work with other former Soviet countries in Eastern Europe, for example the Baltic States.

The Russian-Swedish discussions resulted in projects aiming to raise social work competencies in public authorities, managements and among social workers in Russia. One of the areas chosen for these projects was Saint Petersburg, where several projects aiming to develop new models for social work were launched. The point of departure has been to transfer and adjust Swedish models of social work to the Russian context. The Stockholm University Department of Social Work became responsible for a number of such projects and besides using academic teachers also involved a number of practitioners, such as social workers in disablement services and reformatory staff who could meet and match Russian authorities and partners.

2 Aim of the Study

In this article we examine the conditions for two social work projects where the aim of the study is to describe and understand how the transfer of knowledge and social work methods was received in the Russian context. Which factors facilitated the process and which factors worked against their successful implementation?

3 Methods

Two projects undertaken by Stockholm University in cooperation with different authorities in Saint Petersburg are in focus. One concerned people with intellectual disabilities and the other young offenders. Both projects aimed to develop new models of social work through education of managers, experts and social workers, and to support and supervise activities in the field of social work practice. Data was mainly collected from project reports, with additional interviews with Russian participants in the Young Offenders project and with Swedish project leaders. The project outcome was scrutinized by analysing the project processes and the information engendered compared by using components from a model developed by Cooper & Vargas (2004) that will be presented further on in the article.

4 Social Development and Social Work in Russia

There are only a limited number of scientific social work studies dealing with Russian conditions for the non-Russian reader. Social work is a new scientific discipline in Russia and generally there is not a very strong tradition of international social science publication among Russian academics. It has also been difficult to gain access to reliable data. But among early studies after independence is the Russian Longitudinal Monitoring Study (RLMS), started in 1992 and ongoing, measuring effects of political reforms on health and social welfare ( www.cpc.unc.edu/rlms/ ).

We are now slowly seeing the evolvement of new social developments and an emergence of more respected social work in Russia (see e.g. Iarskaia-Smirnova & Romanov 2002; Iarska-Smirnova et al. 2004; Templeman 2004; Titterton 2006; Penn 2007; Trygged 2009). Russia has undergone severe changes since independence from the Soviet Union. The number of vulnerable groups has increased as well as the income inequalities; the Gini coefficient for Russia increased from 0.26 in 1991 to approximately 0.40 in 1994 and has remained at that level ever since (0.398 in UNDP HDR-report 2007/2008; more information at www.worldbank.org ). The birth rate is low, to which the government has responded by implementing different presidential programmes, for instance Jeltsin’s Children of Russia programme and Putin’s programme to increase financial support to families. But the status of social work as a profession is still weak and unclear even if there is more social work education being offered at universities and other signs of change.

The two projects studied concern persons with intellectual disabilities and young offenders. It is well known that persons with disabilities often had a hard time in the Soviet Union. There has been a strong tradition of “defectology” and it was common with the institutional placement of children with disabilities. Even today in Russia, intellectual disabilities are still sometimes considered to be a disease.

There is also in Russia no juvenile justice, meaning that there is no special legislation for young offenders. Fourteen is the age of criminal responsibility and young offenders in custody are mixed with adults and sentenced according to the Penal Code with the same sanctions. Between the ages of 14 and 18 they may be sentenced to internment in youth colonies (youth prisons) for severe crimes, but as soon as turned 18 they are usually transferred to adult prisons. The tradition inherited from the Soviet Union means a harsh policy on punishment and social workers have a weak position in this system. As a member of the European Council, however, Russia has bound itself to implement Human Rights (HR) also within the penal system and in Saint Petersburg the City Court has showed interest in reforming the juridical position of juvenile offenders.

5 Description of the Swedish Transfer Model

The model for transferring social work practice was an experience based model developed through previous work in Lithuania and other ‘post Soviet’ countries with very similar structures to that in Russia, not a model based on research. Experiences were developed within the framework of the Swedish welfare system and human rights declarations values and the aim was to introduce several alternatives, giving the participants the possibility to compare Swedish experiences with their own work methods and to find out what seemed to be useful and practically applicable.

The projects started with visits to Sweden by Russian administrative leaders and staff as well as representatives from various social committees to be familiarized with the Swedish social welfare system. These study visits were composed of university lectures on Swedish social policy followed by study visits in the field to see the practical implementation of these policies, intended to provide a basis for the planning of concrete projects where the Swedish partner offered a “smorgasbord” for the Russians to pick and chose from. A joint project organization was then set up with Swedish and Russian project leaders.

Besides study visits the transfer model was based on three fundaments:

Education in theory and methods. Lecturers were academic teachers and experienced practitioners. The objective was to give overviews of different fields of social work, concepts, theories and models of working. The lectures also offered an arena for lively discussions and comparisons between the two countries.

A second fundament was “auscultation”; field visits to Swedish institutions for work observation alongside a Swedish colleague for a specified time, where Russian project participants could discuss the concrete work and engage in the exchange of experiences.

The third fundament, supervision/mentorship, means learning by doing and reflection, and built on the exchange of experiences within the working group. Staff groups at Russian work places held regular meetings with a Swedish mentor to discuss difficult cases and how to proceed, the core idea being that these three steps, sometimes in parallel, sometimes consecutively, together would integrate knowledge into competence.

6 The two projects – “Karlsson” and “Young Offenders”

According to the Russian constitution, Saint Petersburg is a separate “federation subject” with authority to adopt and implement regional laws, but the central administrative decision makers in the city, such as the Health Committee and the Social Committee, are disparate, and subordinated to them different district committees. Also, federal administrations sometimes handle the same issues as the local ones, e.g. regarding probation. It is important, therefore, to know the administrative structure well, since differences in local contexts may lead to variations in the outcomes of knowledge transfer.

7 The Karlsson Project

The project name Karlsson emanates from an immensely popular figure in Astrid Lindgren’s books for children. To improve the situation for young adults with intellectual disabilities the project introduced a new concept – both with respect to localities and content – for how to work with this population group. The core idea of Karlsson was to create a workplace for people with intellectual disabilities that at the same time should be a meeting place, where they were to cook and sell food, receiving a small salary. A lot of work went into finding a suitable locality, informing the management and client groups (the youngsters and their parents) about the project, recruiting personnel and overcoming a diversity of other obstacles, such as the sanitary regulations for cooking food. As the project progressed, the staff at Karlsson and others identified new needs, such as for short-term stays and sheltered housing. These new ideas meant expansion into new project phases not planned from the start. In these continued steps forward, the project was much driven by the Russian partner, especially the local Social Committee, which had a strong sense of ownership and responsibility. The local authorities did it in their own way and they did it well.

Inevitably, obstacles arose on different levels: For example, parents were sometimes suspicious, especially at the start of the project. In the Russian federation the parents of a child with disabilities can receive a benefit; the more severe the disability the higher the benefit. There was therefore an incentive for parents to view their child as severely handicapped. Another difficulty was combating ingrained attitudes. The personnel had to face questions like: Why work with these people when the situation is hard for everyone?

However, the project received active support from the local Social Committee. After the start-up of the workplace new needs were identified, such as a place for temporary stays. The Committee supported this idea and further on also the idea of sheltered housing. This project was Swedish supported for altogether eight years. After that, the project has continued to develop a laundry service. All parts are now financed by the Russian authorities within the district budget.

Project outcome

For the Karlsson project the outcome is very evident and visible. There are several new localities and a complete chain of measures in place with a workplace, short-term accommodation as well as sheltered housing, and new ways of working with the client group (the youngsters and their parents) as compared to the situation prior to the start of the project. The Karlsson activities have also been exposed on local television so that at least some information has reached a general public.

8 Social Work with Young Offenders.

Following UNICEF criticism of the treatment of young people in custody, a French-Russian project was started to implement the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), aiming to separate youngsters from adults in custodies and to strengthen the thinking on prevention in the courts when sentencing young offenders. When this French-Russian project came to an end, a Russian judge initiated a new – later Swedish-Russian – project, aimed at developing qualified social work in Saint Petersburg with youngsters suspected of crimes and to provide a better foundation for judges’ decisions on prosecution and sentencing. As the project went on, new ideas were formulated to create a chain of social treatment – from the time the youngsters were caught by the police, through the trial and during sanctions, such as serving sentence in a youth colony or being put on probation – to a new start in the society.

The project consisted of three phases:

The first phase aimed at developing a model of social investigation and social treatment in open care for the youngsters suspected of crimes in order to give the courts a basis for sentence alternatives to custody and punishment. This also meant strengthening the cooperation between judges and social workers. In the second phase the Swedish partner aimed to open a treatment institution for young offenders and to transfer the responsibility for treatment from the State Prison Commission (GUFSIN) to the regional Social Committee. Such a switch implied a change of attitude from punishment to social treatment. It later turned out to be impossible according to Russian legislation to make such a transfer. Instead, the project entered a youth colony and engaged in training its specialists in treatment methods based on social models starting out from the young offenders’ individual needs and social networks. During the third phase the objective was to develop social treatment for youngsters on probation and youngsters leaving the colony to help them achieve a new start in life.

Different professional groups were targeted for training during the different phases, including social workers, judges, policemen, probation officers, specialists in youth colonies and management representatives, and the project involved many different authorities with separate legal frames of reference. A strong emphasis was laid on work with attitudes among staff towards the client group. Altogether the project lasted for eight years.

Project outcome

Social workers, judges, probation officers, policemen, specialists in a youth colony and managements were trained in new treatment methods to be used in their daily work. These methods presupposed the viewing of young offenders as individuals within their social contexts and involved their families and social networks in the treatment as well.

Effects of phase one: Social workers have strengthened their position and more young offenders are treated in open care before or instead of going to trial. The numbers of young people in custodies for adults have decreased. The Government of Saint Petersburg has approved a manual for preventive work and follow-up among young offenders.

Effects of phase two: The responsible youth colony Director of Education has corroborated that the new methods are incorporated into the daily routine of the colony and that new specialists employed are trained in the new methods (interview 2008-09-03).

Effects of phase three: When the project was finalised cooperation had started between individual probation officers and social workers on work with individual youngsters and a steering group representing different authorities had been set up.

Social workers leaving their jobs during the project, but still taking part in the training programme, emphasised in an interview that they had good use of their fresh skills in their new workplaces, especially in work with individual prisoners (interview 2008-09-04).

Handbooks and a textbook in how to use the new methods of social work were made by participants in the project to spread their knowledge. Regional conferences were another means of disseminating these models of social work.

9 Comparing the Projects

To deepen understanding of which factors are important for long-term results we analysed the projects under seven feasibility headings, using the Cooper & Vargas model of sustainable development (2004), which emphasises the conditions of the receiving society and the feasibility of different components. This model was elaborated in the context of environmental sustainability, but we have used it as a source of inspiration and considered the usefulness for our purposes of its different components. This has given us the possibility of comparing the two projects and deepening our knowledge of what has taken place in the encounter between the “new Swedish models” and the “receiving” organisations in the Russian context. We also considered using some textbooks on evaluation (e.g Shaw & Lishman 1999; Weiss 1998) as well as some principles for the evaluation of development assistance (as formulated by OECD in 1991). However, we decided that those perspectives were less relevant to our purpose. In the first place we are looking retroactively at two already finalised projects with no embedded evaluation strategy. Secondly, we are not really scrutinizing the goals of the development projects, we have no outspoken client or public policy perspectives, nor are we looking for cost-benefit aspects. Our interest is rather in understanding why things turned out the way they did in spite of the same transfer model being used in both projects. Looking therefore for more process oriented models we found Vargas’ & Cooper’s model for sustainable development and as this model concerns both global policy and local action we thought it would be useful for the understanding of knowledge transfer from one (international) context to another.

Cooper and Vargas (2004) take their point of departure in the global discussions on sustainable development with special focus on the environment, but social and economic development is also taken into account. To achieve sustainable development there must be a balance between environmental protection, economic development and social development (ibid p.3). In this perspective, sustainable development is also an approach to evaluating plans, programs and operations (ibid). The implementation of policies is crucial and from different UN world conference principles and discussions the authors have formulated a feasibility framework pointing out some different components that it is necessary to implement in order to develop sustainability.

The main components, or feasibilities, in Cooper and Vargas are the following:

-

Technical feasibility means gaining know-how and going from knowledge to action. It means having methods and knowing how to plan for implementing the objectives in society.

-

Legal feasibility highlights the legal frameworks and regulations. In this context it implies both international regulations, such as Human Rights (HR), the Convention of the Rights of the Child (CRC), and Russian federal and regional laws.

-

Fiscal feasibility points to both short-term and long-term budgets and how changes in the system are to be financed. Different monetary sources such as taxes, donations and income-generating activities are included.

-

Administrative feasibility is about the organization of administration and the set up of an administration suitable for the changes to come. It is also about organizing cooperation between different authorities or organizations.

-

Political feasibility explores the possibilities for arriving at political decisions to change the status quo, but also includes awareness of the risks, as political ideologies can change during project implementation and different political interests may emerge.

-

Ethical feasibility stresses fairness and justice as important concepts. Risks of corruption naturally distort changes for vulnerable groups.

-

Cultural feasibility is about deeply rooted values in a group or society.

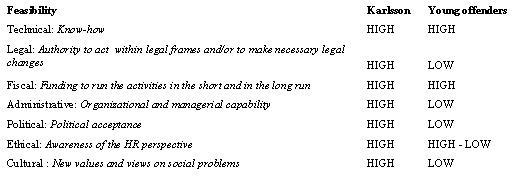

We then constructed a table based on these feasibilities and filled the table with information taken from project documentation (Askerlund et al. 2002; Askerlund 2005; Trygged 2007, Eriksson 2008, Holmberg-Herrström, 2009), simply dividing our findings into two crude categories – high and low. High feasibility means that we could find evidence of support from relevant stakeholders to implement changes. Low feasibility means it was hard to find support for implementing the projects.

Chart: comparison of feasibilities in the Karlsson and the Young Offenders projects

Technical feasibility

The joint project organisations formulated the basic problems as lack of knowledge about alternative methods and lack of humanistic attitudes in the care/treatment of young people with intellectual difficulties and young offenders. The transfer model was used to create alternatives and technical knowledge regarding social work methods and organisation built on HR. The Russian counterparts developed conditions to use their new capacity.

Legal feasibility

The impact of legislation differed between the two projects. Strong local support made it possible for the Karlsson project to adjust to and sometimes overcome legal obstacles to the pursuing of their activities. The Young Offenders project met difficulties especially in the second and third phases as the Federal Penalty Act and other regulations on the federal level contrasted with the ideas of the project and limited the scope for developing social treatment. The possibility of the project to influence the legislation was negligible.

Fiscal feasibility

Both projects were financed by the authorities regarding localities and personnel. The Karlsson project was partly financed by charity to begin with, but was gradually included in the regular city budget. The Young Offenders project was entirely paid for by taxes. Both projects had difficulties with low wages and in the Young Offenders project that was one reason for a high drop-out of specialists in the youth colony.

Administrative feasibility

The projects were dependent on administrative bodies at several levels, all having different impact on the projects’ possibilities to implement their programmes. The Karlsson project was accepted by the central Social Committee in Saint Petersburg and also had the strong support of the local Social Committee. By itself, Karlsson was a strong organisation with a rather independent manager. The Young Offenders project was an attempt to change from the inside authoritarian organisations that were bound to the strict bureaucratic model of the State Prison Commission (GUFSIN), resulting in replacement of youth colony directors and new regulations making it difficult to maintain continuity in the process of change. Also, especially in the third phase of the project, the complexity of local and federal administrative bodies created extreme difficulties.

Political feasibility

Also in this dimension the differences between the projects were distinct. The Karlsson project influenced the local political environment and the enthusiasm of the Russian project-leader could overcome the resistance of local political bodies. But as the Young Offenders project was embedded in the juridical system of the federation it was hard to have any impact on policy. Regular prison revolts in Russia and the fact that two young offenders escaped from the youth colony and committed further serious crimes meant harder restrictions being imposed in the youth colony.

Ethical feasibility

Ethical principles based on the human rights perspective were fundamental in both projects. In the Karlsson project the fairness of selecting a certain group of disabled youngsters was questioned as there are many other vulnerable groups in the society, but the target group was nevertheless accepted for humanistic and practical reasons. Regarding young offenders, there was an ethical awareness, based on the CRC, that it was important to see the individual needs of inmates. At the same time this was hard to implement in practice on account of constant new regulations being imposed and inspections carried out from the federal level.

Cultural feasibility

On the cultural level both projects were a challenge to Russian paternalistic values. In the Karlsson project the view of disabilities as diseases was challenged and the strong tradition of defectology was questioned. In that project an alternative view of young people with intellectual disabilities as nevertheless able persons was developed. In the Young Offenders project attempts were made to temper the traditionally harsh system of punishment from the Soviet era with views on individual needs, re-socialization and preventive work. These views were incorporated by the participants in the project but did not impact on the system of punishment.

Comparing feasibilities

The comparison of feasibilities shows big differences between the two projects. In the Karlsson project it was possible to overcome a wide range of difficulties; feasibility is high on all factors. In the Young Offenders project, on the other hand, there were many more conflicting interests and it was therefore harder to reach any greater degrees of feasibility.

10 Two Social Change Projects – Similar Model but Different Results

The aim of this article has been to understand the different outcomes of the knowledge transfer model in two projects by looking at pre-requisites and process over time. The projects are very far from merely copying or translating methodologies, even if this is what the Russian partner initially was asking for. Instead, they are examples of how projects actively adapt a model from one cultural context to another.

When looking at previous research, the literature on knowledge transfer tends to focus on transfer from research to practice, and certainly not on transfer between social service systems in different countries. In cross-cultural studies and studies on international social work, however, different examples may be found of development work in other countries (see e.g. Healy 2008; Cox & Pawar 2006). Here we refer to a study by Doel & Penn (2007) for the simple reason that the authors write about social work in Russia with foreign (British) support. The study discusses technical assistance, neo-colonialism and mutual trade. The authors find among other things that cross-national projects have a socio-political and not just a technical dimension, that it is important to look for commonalities rather than for divides, and that mutual trade means that each partner has something worth trading.

So what about the Swedish-Russian projects? At first there is an obvious risk of a bias in our perspective as the information we have is mostly that presented by Swedish project leaders. In order to increase our cultural understanding we have visited both projects in Saint Petersburg and gained some additional information from interviews with participants in the Youth Offenders project, but still our information is mostly one-sided. Another difficulty is that since the projects went on for many years it is difficult to isolate what depends on project impact from what would have happened in the society anyhow. For example, there have been parallel projects on probation and social rehabilitation with young offenders in Saint Petersburg that also may have influenced the changes (Sida 2009). This difficulty is also connected to the study method applied, where the main problem is that we did not from the start plan an evaluation but were wise after the event. Finally, we are self-critical in our use of the sustainability model. We have neither made our own definitions nor set up specific project criteria for sustainability but have tried to make use of the Cooper & Vargas feasibilities criteria and may then have missed less visible signs of change.

One quite obvious difference which we did not at first consider was that Karlsson was an entirely new programme starting from scratch, whereas the project with young offenders took place within established settings, and that it is easier to make a change by building something new than to make changes within an existing establishment.

In each project the transfer model consisted of study visits, education, “auscultation” and reflection. There were three mechanisms built into the model to prevent neo-colonial tendencies: the opportunity for the Russians to pick and chose from a “smorgasbord” of social work projects, a joint Swedish-Russian project management, and a Russian ownership of the projects. With Russian ownership we mean that project activities were decided upon by the Russians, who were also responsible for their implementation. So what are the results on Russian soil? When we compare the two projects using the chart elaborated from Vargas & Cooper we find three particularly important areas where conditions differ. One is in legal feasibility. In the Karlsson project the local authorities had legal opportunities to make changes and to implement laws on their own. In the project with the young offenders the Penal Code and the system of control was subordinated to federal laws. There are e.g. strict regulations concerning prison regimes, with regular inspections. As an example told by one of the local project leaders, one youngster tried to escape from the colony, but was captured before leaving the prison grounds. As a consequence he was put into isolation; there was corporal punishment for other prison inmates for not stopping him and an endorsement for the staff and prison leadership for the management of this incident. Changes of penal codes and regulations of colonies are decided at Russian federal level and these turned more rigorous during the project.

Regarding administrative feasibility it is obvious that both projects show complex administrations with different stakeholders representing different authorities. Karlsson was a more coherent activity restricted to one district only with one working group (later on two) and a very active local project leader who succeeded in carrying out and further developing the work. In the project with young offenders the different levels – local, regional and federal – were all exerting influence on the scope for action. Especially actions at federal level, leading to the replacement of colony directors and control inspections of staff and decisions made on a general level, influenced the possibilities of social change. But there were also the different steering groups’ difficulties in coordinating their different tasks.

It is also clear that political feasibility, understood as importance on the political scene, differed between the projects. While the change in treatment of intellectually disabled persons caused comparatively small resistance, issues of crime, prosecution and punishment are part of a vital overall policy in any state governed by law. Political changes in this field are an issue for the entire society. In this respect the Young Offenders project was a more ‘politically challenging’ project than the Karlsson project with young disabled persons. A work by McAuley & MacDonald (2007) with data from Saint Petersburg suggests that politicians seemed to have an even tougher attitude than the general public concerning youth crime and juvenile offenders.

Both projects have had their own difficulties to struggle with. For Karlsson it has much been a process of trying to shift generally held views of impairment from disease to (partial) disability and to show that these youngsters also have capabilities, challenging the system of “defectology”. When we look at the most visible results of the projects today (2009) we can see that the Karlsson project is still standing strong and is continuing to grow, having been integrated into the local municipality.

A difficulty common to both projects, however, although especially so in the Young Offenders project, was the constant shifts in personnel. By the end of the second project phase, almost all the personnel had quit their jobs, many times shifting to better paid work. It is possible that they could make use of their training in their next workplace but again this is hard to measure.

Both interviewed project leaders agree that in these projects it was more successful to work with the regional level only. The Karlsson project was much owned by the local Social Committee. It was not actively pushed by Saint Petersburg’s central Social Committee, which at the same time means that project impact largely remains on the local level. In the Young Offenders project there was a mix of federal and regional participants but this brought in too many layers and was mostly confusing.

11 Conclusions

The method of knowledge transfer does not predict the project outcome. There are too many complexities. Our comparison shows that it was easier to construct a new project than to make changes within an establishment. It is also necessary to know the local political and administrative structure as the range of power played a role for what it was possible to achieve. The Karlsson project received strong local administrative and political support. In this project it was more effective to work with the local structure only as compared with mixing the regional and federal levels. Federal laws strongly regulate and limited the possibilities in the project with the young offenders. Ethical and cultural values also played a role. The heavy personnel turnover – especially the replacement of colony directors in the Young Offenders project –created difficulties.

References

Askerlund, Y. 2005: Att ta språnget utan återvändo. Hållbar utveckling i internationellt socialt utvecklingsarbete – exemplet Karlsson. [To take the step with no return - Sustainable social development work - The Karlsson case. Published in Swedish] Magisteruppsats. Stockholms universitet, Institutionen för socialt arbete

Askerlund Y., Kukulidi G., Bergman Eriksson S., Engdahl C. 2002: Utveckling av det sociala arbetet i Sankt Petersburg. Stencil. Projektrapport (delrapport) till Sida juni 2002. [Development of the social work in Saint Petersburg. Project report. Published in Swedish] Stockholms universitet, Institutionen för socialt arbete

Cooper, P. and Vargas, C M. 2004: Implementing Sustainable Development. From global Policy to local Action Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers

Cox, D. and Pawar, M. 2006: International Social Work. Issues, Strategies and Programs. Thousand Oaks: Sage

Doel, M. and Penn, J. 2007: Technical assistance, neo-colonialism or mutual trade? The experience of an Anglo/Ukranian/Russian social work practice learning project. European Journal of Social Work, 10 (3), 367-381

Eriksson, B. 2008: Socialt arbete med unga lagöverträdare – förhållningssätt och samverkan mellan myndigheter i ett projekt i St Petersburg. [Social work with young offenders - attitudes and cooperation between authorities in a project in Saint Petersburg. Report published in Swedish and Russian] Stockholm University. Inswed.

Healy, L. 2008: International Social Work. Professional Action in an Interdependent World. 2nd edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press

Holmberg Herrström, E. 2009: Socialt arbete med unga lagöverträdare i St Petersburg, fas 5, 2006- 2008. [Social work with young offenders in St Petersburg phase 5, 2006-2008. Report published in Swedish and Russian] Stockholm University, Inswed.

Iarskaia-Smirnova, E. and Romanov, P. 2002: "A Salary is not Important Here": The Professionalization of Social Work in Contemporary Russia. Social Policy & Administration 36 (2) 123-141

Iarskaia-Smirnova, E. Romanov, P. and Lovtsova, N. 2004: Professional development of social work in Russia. Social Work & Society, 2 (1) 132-138

Karajan, V. 2006: Handbook. Youth Centre Contact. St Petersburg

Lyons, K. 2006: Globalization and Social Work: International and Local Implications. British Journal of Social Work (36) 365-380

McAuley, M. and MacDonald, I.K. 2007: Russia and Youth Crime. A Comparative Study of Attitudes and their Implications. British Journal of Criminology 47, 2-22.

Shaw, I. and Lishman, J. 1999: Evaluating and Social Work Practise. London: Sage.

Templeman, S. 2004: Social Work in the New Russia at the Start of the Millennium. International Social Work 47, 95-107

Titterton, M. 2006: Social Policy in a Cold Climate: Health and Social Welfare in Russia. Social Policy & Administration 40 (1) 88-103

Trygged, S. 2007: Internationellt socialt arbete – I teori och praktik. [International Social Work - In theory and practise. Textbook published in Swedish] Lund: Studentlitteratur

Trygged, S. 2009: Social work with vulnerable families and children in 11 Russian regions. European Journal of Social Work 12 (2) 201-220

Weiss, C. 1998: Evaluation. Second edition. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice Hall

OECD 2009: www.oecd.org DAC Principles for Evaluation of Development Assistance. OECD, Paris (OECD 1991, Reprint of original content 2008) [accessed 2009-03-16]

Worldbank 2009: www.worldbank.org [accessed 2009-03-17]

Sida 2009: www.Sida.se Det svenska stödet till reformprocessen i Ryssland 1991-2008 [accessed 2009-06-21]

UNDP 2009: http://hdrstats.undp.org/indicators/147.html [accessed 2009-03-17]

Interviews

Yvonne Askerlund, former Karlsson project leader, Stockholm University/INSWED.

2009-03-20

Eva Holmberg-Herrström, former Young Offenders project leader, Stockholm University/INSWED. 2009-03-31

Olga Egalina, responsible for education in Youth colonies, St Petersburg. 2008-09-03

Participants in the Supervision Group of Kolpino Colony. 2008-09-04

Acknowledgements:

We wish to thank SAREC for funding within the programme “Developing International Child Care Research”. We are grateful to Gabrielle Meagher for valuable comments on a manuscript draft. We also wish to thank Yvonne Askerlund and Eva Holmberg-Herrström for help with acquiring data and information about the two projects.

Author´s Address:

Sven Trygged, Ph D / Bodil Eriksson, Ph D

Department of Social Work

Stockholm University

SE 106 91 Stockholm

Tel: +46 8 161332

Cell: +46 73 7766986

e-mail: sven.trygged@socarb.su.se / bodil.eriksson@socarb.su.se

urn:nbn:de:0009-11-24655