Single mothers figuring out their future family life – understanding family development after separation and divorce drawing upon the concept of configuration

Claudia Equit, Leuphana University Lueneburg

Matthias Euteneuer, Fliedner Fachhochschule Düsseldorf

Uwe Uhlendorff, Dortmund University

1 Family development after separation and divorce: State of the art

There is a large body of research on one-parent families and very many research topics. However, there is a basic consensus as regards the disadvantages of single-parent families: for example, single-parent families face an increased risk of poverty; they often lack the necessary time resources for child-rearing and for supporting activities for the child(ren), and they are often confronted with stigmatisation. Overall, in comparison with the (idealised) nuclear family, one-parent families are labeled as a worse and more risky family constellation (Caroll 2018; Brighouse & Swift 2014; Elliott et al. 2015; Harris 2013; Freistadt, & Strohschein 2012; Oswell 2013; Phoenix 2013; Lee & Hofferth 2017; Walker et al. 2008; Zartler 2014). However, more detailed studies show that children’s problems in single-parent families are more a consequence of financial hardship and changes in family structure than of single parenthood itself (Beckmeyer et al. 2014; Golombok et al. 2016; Nixon et al. 2015; Ryan et al. 2015; Schroeder et al. 2010).

The latter highlights an important blind spot: many of the studies treat single-parent families as a homogeneous phenomenon,[1] although much of the research shows the opposite. For example, there are several reasons for the formation of a single-parent family (widowhood, separation/divorce or single parenthood by choice) and single-parent families are quite diverse as regards parental involvement of the separated partners and their day-to-day living arrangements (Arendell 1996; Castrén 2017; Golombok et al. 2016; Schneider et al. 2001; Fallesen, & Gähler 2020). Furthermore, studies indicate that single-parent families are not a stable phenomenon but are often a transitional stage to other family forms such as stepfamilies or blended families (Castrén 2017; Entleitner-Phleps, & Rost 2017; Schneider et al. 2001). Considering studies that indicate that neither the heterogeneity of the group of single parents, nor the effects of power, are well-reflected in the knowledge and interventions of professionals (Krüger 2016), it is important to examine the different family figurations and perspectives of single parents on the one hand and convey this knowledge to social workers in order to allow interventions to be more individual-case orientated on the other hand.

At all events, there is a lack of long-term studies investigating the transition processes from single-parent families to other family constellations. Only a few studies investigate co-parenting by separated heterosexual couples in a longitudinal design (Walper et al. 2020; Marchand-Reilly, & Robin 2019). Several variables influence the relationship between children and parents (ibid.). Some studies stress the complexity of relationships and changes in family constellations and co-parenting after the separation/divorce of homosexual couples (Goldberg et al. 2014; Gahan 2019). Transitions in homosexual families tend to be complex when dissolution/divorce occurs because diverging segments of parenthood must be negotiated (Vascovics 2009). Only a few studies examine single parents’ future perceptions and desired family configurations (Castrén, & Ketokovski 2015; Poveda et al. 2014; Smyth 2017).

2 Theoretical background and methodological approach

This contribution to the understanding of family development after separation or divorce aims at a closer understanding of the reflection processes that single mothers undertake, as regards the formation of their family network. We also aim to understand how their desires, values, and wishes influence their conduct of family life. The term ‘family configuration’ plays a crucial role here: based on Norbert Elias (1971, 1976), we understand family configurations to be a constantly changing and dynamic network of human relationships. Family configurations in this sense can be understood as mutually coordinated tasks and obligations, as well as the associated mutual expectations and dependencies parents perceive with regard to the upbringing and care of children. To that end, they enter socio-spatial arrangements, which can also encompass several households (Widmer et al. 2008, Castrén, & Ketokivi 2015). Preliminary studies (Euteneuer, & Uhlendorff 2020) confirm that parents are able to reflect on their family situation at a high level, taking into consideration a multitude of factors, perspectives and resources when reviewing their current day-to-day family life. At the same time, they are striving to retain or gain control over day-to-day family life as well as family life in the near future. Furthermore, parents try to cope with limited resources and options, with the dependencies that evolve from family relations, health issues as well as from broader socio-economic circumstances and life situations. The theoretical ideas of Elias seem to provide a fruitful understanding of these reflection processes. Elias highlights that people are fundamentally orientated towards, and dependent upon, other people throughout their life. People in this sense only exist ‘in the plural’, as connected beings. They are to be thought of as a part of a configuration: a structure of mutually-oriented and dependent people. Configurations can be altered by individual actions, but they also form and influence individual actions, through a web of powerful interdependences and the economic and social resources which are contained within. (Elias 1976, p. LXVII).

The presented research results are based on interviews with single mothers. We define single mothers as women who are living alone with one or more child(ren) in a household.[2] We used a sample of 30 single mothers[3] from a larger longitudinal study, which was funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG). Of the 30 mothers, seven have a migration background. The sample covers families from different socio-economic status groups in equal shares. The median age of the interviewees is 34, the age of the children ranges from 0.2 to 17 years. Most of them live, or have lived, in heterosexual partnership constellations, but two of them also live, or have lived, in homosexual partnerships. We interviewed all participants twice, at 16-month intervals. Building upon three biographical time-levels (past, present and future/desired family life), we developed a guideline for semi-structured interviews. This guideline covered major dimensions of everyday family life such as: the composition of the family network, time schemes, care patterns balancing care for oneself and care for others, division of work and role models, couple relationships (if existing), intergenerational relations and conflicts within the family, as well as child-rearing practices. In the analysis presented here, we focus on the family network which is, of course, closely connected to care patterns, division of labour and (if existing) concepts of the couple relationship and its connection or integration into the family web. We analysed the interviews by means of ‘documentary method’ (Bohnsack 2003).

Bohnsack (2010, p. 100) distinguishes between explicit "reflexive" knowledge on the one hand and implicit "incorporated" knowledge "which gives orientation to action" on the other hand. Following Bohnsack (2003, p. 199), we assume that orientation patterns in the sense of "incorporated knowledge" are a crucial part of how single mothers perceive the family configurations in which they are involved, as well as being a key driver either for desired changes in configurations or for their maintenance or adaptation to the changed circumstances. The analysis contained the following steps: First, a content overview was prepared for each interview. Second, we elicited the explicit knowledge of the interviewees and their implicit, “incorporated” knowledge regarding conducting family life and with regard to desired family figurations. In addition, we reconstructed the wished future family configuration of the interviewees. Third, the results of the analysed interviews of the first interview wave were summarized with regard to the current and desired family configurations, as well as the resources and challenges of conducting family life. Fourth, the results of the first interview wave were compared with the second. The results of each case were summarized. Fifth, we classified the cases using basic characteristics of the current and future family configurations and condensed them into a typology (Kelle, & Kluge 2010). In the following, we present selected results of our investigation in three steps: A typology of family configurations as perceived by the single mothers (3.1); an analysis of the desired family configurations (3.2); and – as the main part of our analyses - the reconstruction of orientation patterns underlying the configurations and the desires for change or maintenance (3.3).

3 Research Results

3.1 Family configurations from the parent’s point of view

We identified six types of family configuration which single mothers use to describe their family web. They are quite similar to the heuristic Schneider et al. (2001, p. 28ff.) developed to analyse their data, but while they follow the perspective of children and use objective criteria to categorise their data, we concentrated on how mothers conceptualise the family figuration.

The following table shows an overview of the types of family figurations in which they currently live or which they desire. The table shows the distribution of cases; the numbers in brackets refer to the desired constellations.

Table 1: description of family configurations, distribution of cases among the individual types

|

No. |

Type |

N |

Description |

|

1 |

living apart and co-parenting |

9 (4) |

Both single parents are seen as being responsible for upbringing and taking care of the children, even though they have split up as a couple. The commitment may differ significantly in terms of time spent on family obligations, but in principle, both parents are seen as having the same rights and obligations. If one of the single parents has a new partner, this partner will not take significant responsibilities for the children. |

|

2 |

living apart and co-parenting with support from significant others |

8 (2) |

Same as above, but with an additional network of relatives (often grandparents, sometimes siblings) and/or friends supporting the family, without taking parental roles. |

|

3 |

sole responsibility |

6 (4) |

The single mother sees herself as the sole responsible person raising her children without support from relatives, separated parent or friends. Mostly there is no or virtually no contact with the separated parent. All relevant tasks and decisions regarding child and family issues are her sole responsibility. |

|

4 |

sole responsibility with support from significant others |

3 (2) |

Same as above, but with a network that helps with raising children and/or provides financial and/or emotional support. None of the supporting persons is seen as having a parent-like position. |

|

5 |

multiple parenthood |

3 (15) |

More than two people have a parental role as regards the dependent children and have parental obligations in their day-to-day life (often with differentiated levels of responsibility). |

|

6 |

stepfamily |

1 (3) |

Single mothers are in a relationship with a new partner, in a living-apart-together configuration. The new partner is seen in a parent-like position, they take on significant care functions for the children and somehow substitute for the separated parent who is no longer seen as taking on a parental role. Mostly, there is no or only very little contact with the separated parent. |

3.2 Desired family figurations

Single parents were also interviewed as to which type of family configuration they aspire to for their future family life. There were 17 single mothers, out of the total sample of 30, who wished to live in a different family configuration in the future. The most favoured figuration was the “multiple parenthood” type (Type 5; N=15). Remarkably often, parents with current family configurations of Types 1-3 aspired to a “multiple parenthood” figuration (10 cases). Three interviewees wanted to transform their family configuration into a “stepfamily” (Type 6).

A discrepancy becomes apparent between the desired and the experienced family configurations of single mothers: On the one hand, multiple parenthood and stepfamily configurations were aspired to by many as their future family constellation. On the other hand, there were only a few cases, in which this configuration was achieved. Only three single mothers lived in a “multiple-parenthood” configuration (Type 5), and two of them lived this constellation already before separating. Additionally, one mother lived in a “stepfamily” configuration (Type 6).

Furthermore, it must be acknowledged that almost half of our sample considered their current family configuration to be optimal and wished to see only slight changes in their future day-to-day family life. More than half of the single mothers in the Type 3 “sole responsibility” category and two of single mothers in the Type 4 category “sole responsibility with support from significant others” showed consistent priorities and wanted to maintain their family figuration. But it is important to notice that the single mothers of both types differed highly in their living conditions. Three single mothers in Type 3, who wanted to keep their current figuration, faced huge problems such as their own chronic disease or multiple disabilities of the children; both were often closely related to poverty. The interviewees could not imagine integrating a new partner into their family due to their problematic life situation. In contrast, solely responsible single mothers “with support from significant others” (Type 4) considered their family figuration to be resourceful and functioning: There was a complex caring system in place; no additional caring person seemed to be needed and, due to the integration of the single mother in the labour market, these families were in a better economic situation than other interviewees in our sample. Two out of three cases wanted to remain in this configuration. One single mother wished to form a stepfamily with a new partner (Type 6).

3.3 Orientation patterns

In the following, we will present the orientation patterns. They are key drivers with regard to the desired transformation or perpetuation of the current family configuration of single mothers. The results show that different pathways for remodeling family life were often based on a similar orientation pattern. As a result, a total of five orientation patterns were reconstructed. Of the 30 cases in the sample, all could be assigned to the patterns described below:

Orientation pattern 1: Keeping the old triad on track and trying to integrate a new partner (N=13)

This pattern is often presented by mothers where the separation had been comparatively recent (mostly between one and two years). On the one hand, the single mothers want the other parent to maintain their parental functions despite the separation. On the other hand, they strive to integrate a new partner into the configuration. They should be involved in household and child-rearing tasks, and thus be ‘assigned’ parenting duties on a day-to-day basis while, at the same time, they should not replace the separated parent. Seven of the 13 mothers following this pattern are already in a new partnership, the other six could imagine having one.

This orientation pattern serves as a key driver for the process of negotiation towards multiple parenthood. In our sample, this pattern was the most common (13 out of 30 cases). The interviewees live in quite different family configurations: six parents are embedded in configuration 2 (living apart and co-parenting with support from significant others); five in configuration 1 (living apart and co-parenting without support from significant others); one in configuration 3 (sole responsibility) and one in Type 5 (stepfamily). The current contact and the role of the separated parent varies: Most of the interviewees (11 out of 13), who are following this orientation pattern, are still co-parenting with the other parent. In some cases, they take on essential and regular care functions in everyday life. In other cases they play only a minor or occasional role compared to the mother we interviewed, but the interviewees wished that their ex-partners would be more involved in active parenting. We even found two cases, where the other parent actually seems to refuse to take responsibility, but the interviewees still see them in a parental position and would like them to (re)engage in active parenthood.

Most of the mothers have clear ideas about how multiple parenthood roles are shaped and balanced. The interviewees seem to follow a common familial order, as is shown in the case of Ms. Falke. She lives in a household with her son Benny, divorced from her ex-husband, Leon - Benny's father - to whom she was married for about three years. Although separated, she told us that they get along "quite well", and Leon is involved in care responsibilities for their son. According to Ms. Falke she and her ex-husband will “automatically” remain connected in the future because of their common child. While she has not yet entered a new relationship, Leon has a new girlfriend. Ms. Falke can well imagine that the new girlfriend will become part of the family. Ms. Falke gets along well with her and Ben likes her, too. She can easily imagine her ex-husband having children with his new partner and hopes that everyone will continue to get along well with one another. Ms. Falke can also imagine having a new partner:

“Well, at the moment I don’t know [LAUGHS]. But definitely at some point.”

She would like to have another child, as she has always wanted to have three children. It is interesting that Ms. Falke sets clear conditions for the new partner:

"So if I had a new partner now, I wouldn't move in with him right away. Child rearing and so on, that is still my and Leon's (child's father) business. I mean, if you have a relationship for a longer time, then maybe your partner has some influence on the child. But not at the beginning. This should remain, that Leon and I make the arrangements (...). I think that it will take a little longer for me to have a relationship with someone again and that we share our lives.”[4]

This case illustrates a typical familial order for this group: The two biological parents are separated, but they still share the main decision-making regarding the rearing of the children, although there are new partners involved who could at some point overtake some parental tasks. The orientation pattern is based on certain normative expectations: The principle motive for maintaining the old triad is the conviction that the two parents are the primary caregivers for the joint children and bear responsibility for their upbringing, even after separation. However, the child’s right to active parenting by both their father and mother is balanced against the parents’ desire for a new and happy partnership. The new partnership is also based on the idea of sharing a common life (in a common household). Living together naturally includes also sharing some responsibility for the upbringing of the partner’s children. However, the new partner must accept that the main parenting responsibilities and decisions in this regard lie with the biological father and the mother of the child. On the other hand, the child from the first relationship is expected to accept the parents’ desire for new partnerships and eventually more children. The mothers also hope that existing children will fit into a relationship with potential new siblings.

Our long-term study showed that none of the 13 interviewees could achieve the desired form of multiple parenthood within the time span of the research project. In several cases, the new partner moved out again after a short time. In other cases, as is the case of Ms. Falke, the ideal partner has not yet been found. Studies on multiple parenthood point to the difficulty of negotiating the different needs of all family members. This configuration needs to meet with the agreement of all parties involved.

Orientation pattern 2: Concentrating on the mother-child-dyad (N=5)

For five mothers, the integration of a new partner or the maintenance of the original parent-child triad plays no role at all. They are living in a configuration of “sole responsibility” with or without support from significant others (Type 3 or 4) and do not want to put an end to the configuration they are currently in but rather to improve it. They have not been in a new relationship since their separation/divorce. The children's fathers play no role in the family configuration. All in all, none of the respondents have any contact with the separated father. They do not even wish to find a new partner. The mother-child dyad is at the centre of their lives, from which they derive complete fulfilment.

All the mothers following this orientation pattern share the fact that their children are older than seven and that the separation from the father dates back several years. Although all interviewees live in dyadic family constellations, their living conditions are different. Three out of five report no further contact with relatives or friends.

"So, my family is just, well, my kids and me. That's all." (Ms. Lösche)

They are solely responsible for the care and upbringing of their children. Half live in precarious circumstances, characterised by poverty and unemployment. In addition, the mother’s physical and mental illnesses, sometimes coupled with their children’s disabilities, are cited as constituting an additional burden on their daily lives. Three interviewees receive professional support from social workers which helps them to cope with their daily lives. This is the case for Ms Lösche:

“I have a social worker who saves me mentally. I can talk about everything. And I can share my worries and then maybe develop some ideas, how I can change something, or.... (.) Hmmm (.) Yes, or even someone to talk to or so. [...] So that helps me a lot."

Two other interviewees receive support from friends and relatives. As mentioned above; all respondents would like to remain in the current family constellation, and they are not looking for new partners. However, the reasons for this vary. The first priority for mothers without a network of relatives and friends is to change their stressful daily lives:

"I wish of course that our life could become calmer again, more relaxed. That we have an ordered life, that the pressure is simply taken off us, that we no longer have all the problems with the social security office [...] that my life will then be calmer, that my daughter no longer has all these psychotherapy appointments. That she can go out to play, be a child again! That is important for me, of course, and that I will be fit enough to support her in everything she wants to do. That I can also go on a trip with her again." (Ms. Stark)

Other parents are proud that they have learned to manage life alone without a partner, as in the case of Ms. Jelling:

“Yes, I can hang up a picture even if it is sometimes crooked, but crooked is ‘in’ (LAUGHS). I don't know why I need a man, or a woman or so.”

All mothers in this group are oriented on the mother-child dyad. It is their mission in life, a project that gives their lives meaning. To achieve stability within the family the mothers establish some kind of parental autonomy. They are concerned with improving or maintaining their physical and emotional well-being, as parents, but also for the child/children as well as their economic living conditions. The integration of a possible new partner represents a risk as regards the realisation of this life project; a new partner could impose an additional burden or additional conflicts and complications that these mothers do not wish to deal with.

Orientation pattern 3: Intensification of support through social networks, open to a new partnership but maintaining the mother-child dyad (N=2)

Interviewees following this orientation pattern live in a mother-child dyad that is very well supported by a network in their day-to-day life (configuration 4). The interviewees are open-minded to the idea of a new partner who can perform care tasks, but who is not expected to take on a full parental role. An example is Ms. Yildiz (42) who lives alone with her two sons (17 and 14 years old) in a large flat in Germany. Her husband died in a car accident five years ago.

"That's when my life completely turned around. Fortunately, I have a big family." Her mother looked after the children while Ms. Yildiz re-trained and worked. Her sister-in-law also helped her during this time; she often spent weekends at her sister's house together with the children. "I think that's very nice. I think having such a big family is actually quite good. I get a lot of support there."

She describes her situation as a single mother as follows:

"It's a big responsibility. Well, you have to carry it. And of course I try to do my best. I can't be a father, of course, but I try to fulfil my role as a mother as well as I can so that they have an image of it later on in their lives. I don't know how I'll manage, but I'll try my best (laughs)."

She can imagine having a new partner:

"Yes, when the children are out of the house, that's possible. But he must not interfere in the upbringing of my children."

Both cases that follow this orientation pattern agree that the new partner should take on household tasks but not a full parental role. The interviewees want to be the ones who make all the important decisions for their children. For the two women the autonomy and independence they have achieved through their career is especially important to them. This orientation pattern is based on normative concepts similar to the first pattern: in their eyes, the biological parents are the children’s main caregivers and they are the ones who are responsible for their upbringing and wellbeing. But in contrast to the group of parents in orientation pattern 1, the father is missing as a result of death or insurmountable conflicts. In their eyes, the missing father cannot be replaced but only compensated for by a network of caregivers, possibly including a new partner. On the other hand, the parents are proud that, as a single mother, they have managed to combine household duties, raising the children and working full time. In this way, they are fulfilling their desire for self-fulfilment at work and the child's right to security and care. At the centre of their life plan is the mother-child dyad surrounded by a supportive social network which might also include a new partner. They expect their partner to accept this and to integrate into the supporting network without taking on the role of parent. However, this is also a challenge.

Orientation pattern 4: Keeping the parent-child triad on track (N=6)

This group of mothers has in common that their orientation pattern is characterised by the adaptation of the parent-child triad and the concept of the nuclear family to new life circumstances. In other words, they stick to the principle of the triad and the idea that a child needs one mother and one father (two parents and both genders), and they try to adhere to this concept with the former partner or with a new partner. In their thinking, multiple parenthood – in the sense of more than two parents raising a child – represents a negative counterpoint. Consequently, there are two different approaches to a remodeling of the family configuration as it had existed before the separation. One subgroup forms, or tries to form, a step-family with a new partner, after contact with the other biological father of their children has broken up (three of six cases). Other mothers succeed in maintaining the biological parent-child triad despite being in separate households and having terminated their intimate partnership (three of six cases). One example of the latter is Ms. Aksoy who separated from her husband eight years before and who lived together with her 18-year-old daughter. In the first interview she described her family configuration as “Living apart and co-parenting” (Type 1) and she stressed the need to maintain this model. Right from the start, her aim was to keep the impact of the break-up of her partnership on family life as minimal as possible, especially with regard to her daughter. That means that her efforts were directed towards ‘conserving’ the structure of the nuclear family, even though her partnership with her husband had broken up. Right at the beginning of the interview, she stated very clearly that she and her ex-partner were “no longer husband and wife, but still mother and father”. However, despite being aware of that, her interview clearly reveals the tensions resulting from adherence to the nuclear family concept on the one hand and the family reality on the other; the latter partially deviates from that ideal. This begins with the fact that her husband has left the family residence, while she and her daughter continue to live there. This means that it is mainly Ms. Aksoy who cares for her daughter on a day-to-day basis, while her ex-husband only ‘sees’ her, albeit regularly. Thus, the triad at the core of the family is not equally balanced. This is clearly reflected in the way Ms. Aksoy speaks about her family:

“My daughter is 18 now… Actually, I am trying to say ‘our daughter’ all the time, because my husband cares for her too, but somehow it’s always ‘my’ slipping out!”

Furthermore, Ms. Aksoy sometimes thinks about having a new partner. But establishing a new partnership would, in her eyes, endanger her current family configuration. Thus, when mentioning this desire, she clearly states that this new partner could never be a father to her daughter and, when thinking about what family life with a new partner might look like, Ms. Aksoy combines the idea of having a new partner herself with the idea of her daughter leaving her family of origin by establishing a “steady relationship” of her own.

Overall, mothers with this orientation pattern stick to the conventional image of the nuclear family, even though they have separated from their partners. Due to constant tensions between adherence to the concept of the nuclear family and, at the same time, many deviations from this concept, it is ‘hard work’ to prevent further changes to the configuration. As a precaution, the roles and position of both parents must be ’normalised’ and protected from any revision or any attempt by (potential) new or former partners to claim the parental role for themselves as well. In summary, this pattern is characterised by the normative concept that children need exclusively one father and one mother as caregivers. In general, these are the biological parents of the children. In three cases where, according to the interview, contact with the biological father had irretrievably broken down, was the involvement of a second non-biological parent considered. For the other interviewees, the integration of the new partners into everyday life seems to be too complicated and postponed to a later stage in life when the children have "left" their family of origin.

Orientation pattern 5: Staying queer? Negotiation-based multiple parenthood (N=4)

Our research also touched on the question of which orientation pattern is followed by mothers who were already living in a multiple family configuration before separating from their partners (four cases). It is interesting that all mothers were trying to maintain the "original" multiple-family configuration. Three of the four cases with this orientation pattern were living in a multiple configuration when we interviewed them (family configuration 5). One mother has three children from two different fathers and has been living in such a constellation, but one of the fathers had quit his family duties when we interviewed her. At the time of the interview, she was co-parenting with the father of one of her children (family configuration 1), but she wanted to renew the previous configuration, in which both fathers were seen as fathers for all of the children. This orientation pattern is characterised by adaptation of the original concept of multiple parenthood to the changed family conditions (separation, diverging demands and expectations as regards childcare) and renegotiating this concept with the other parents involved. Out of the four cases, two have a heterosexual constellation, the other two are rainbow families. All four have separated from their partners, but they are making great efforts to maintain the multiple-parent family constellation in which they lived before.

The dominant normative orientation is that the biological parents are important as caregivers for the children and they must not withdraw from this obligation. From the mother’s point of view, the children have the right to enjoy intensive contact with their biological parents. Nevertheless, other adults could take the role of social parents, if all parents agree upon that. The two homosexual and bisexual mothers we interviewed had agreed on an arrangement before they conceived the child, whereby the biological parents and their partners would be assigned clearly defined roles in a multiple family configuration. Other adults (new partners of the parents after separation) should not be included in the figuration in the role of parents so as not to endanger the children's well-being. In this context, Karin's statement is significant:

“I've always said, hey, this is our constellation, there are four of us, this is our constellation, I want to keep it that way and not have more people come in.”

Despite the separation and divorce from her wife, Karin wants to maintain the original constellation of two mothers and two fathers. She assigns a clearly defined role to her new partner:

“I think there's a difference when a new partner comes along, then I think that's not a family, so I separate it. I'm now with a man and a partner and I've said from the beginning that I have this constellation, that's how it looks, but it's not that I'm looking for a father for my children. So, somehow it's clear to me that this is here … and you're my partner.”

Also the heterosexual mothers made clear agreements with the biological father regarding the family role of new partners before they moved in and took a social parenthood role.

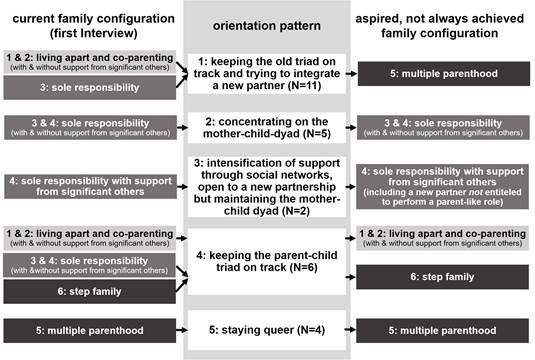

Figure 1: Connections between current family configuration,

orientation patterns, and aspired family configuration

All in all, the five orientation patterns we have worked out are all linked to certain current family configurations and serve as a starting point. They mostly lead to a specific desired configuration, with the exception of orientation pattern four, where there are two ways to reach the desired configuration, depending on the current figuration. There is usually more than one possible configuration as a starting point and there are usually several possible orientation patterns single mothers living in the same current figuration choose (cf. Figure 1). Overall, this strongly supports Elias' idea that configurations, as powerful webs of relationships, pre-structure but do not determine individual possibilities for action.

4 Conclusion

Elias' concept of configuration proved to be helpful in understanding and describing the empirical results in at least three ways:

Firstly, Elias teaches us to consider that changes in the structure of figurations go along with “the increase or reduction of interdependencies and gradients of power” (Quintaneiro 2006, no page reference). All interviewed mothers reflected on drastic changes and the reorganisation of their family constellations as a result of separation. The orientation patterns described above reflect, in many ways, that these transformations include changing power levels. The women following orientation pattern 2, “concentrating on the parent-child-dyad” for example, clearly reflect issues of power, albeit divided in two different subgroups: on the one hand, there are single mothers who are embedded in social networks and integrated into the labour market. Based on stable economic and social resources, they see themselves in a relatively powerful position and experience high levels of autonomy in their daily family life. They intend to stick to the mother-child dyad because any involvement of additional people might endanger the resourceful and powerful position they have developed, within their web of dependencies ever since the dissolution of their partnership. On the other hand, single mothers who are left to their own devices by their partners, and experience a lack of social and economic resources as well as high levels of stress, also show a preference for the parent-child dyad. These mothers see themselves in a less powerful and autonomous position and fear further loss of control if additional persons are involved in their family figuration. They try to avoid this, not at least because many of them are already under public scrutiny due to their involvement with childcare services.

Secondly, Elias’ concept of the individuals as homines aperti (open individuals who are fundamentally orientated towards others due to their needs) helps us to understand the wish of many single mothers to be involved in new relationships, in the future. The ambiguity, between the wish and need of individuals to be connected with others on the one hand, and questions of power and (inter)dependency on the other hand, might also explain one outcome of our study: We found that many respondents, e.g. in the context of orientation pattern 1, “Keeping the old triad on track and trying to integrate a new partner”, were oriented towards multiple parenthood as an “ideal” and desirable family figuration. However, our research shows that hardly any of the individuals in our sample have achieved this configuration. Multiple parenthood implies the participation of many caregivers and makes it possible for an intimate partnership to be integrated into a family unit after a divorce. However, it also involves an increasing complexity of interdependencies and is, potentially, accompanied by a loss of power for the parents already involved in the family configuration. Multiple parenthood depends on the consent of all family members. Thus, it is very understandable that – for example, after separation of a couple relationship within a multiple parenthood configuration of four parents – the interviewees are not in favour of involving new partners as further parents, but wanted to stick to the original network.

Finally, Elias explains that different configurations can lead to uncontrollable dynamics for the people involved, raising all sorts of dilemmas. At the same time, people in these configurations are able to gain an understanding of their situation by distancing or detaching themselves from the situation. The reflection processes observed in the interviews could be understood as attempts to achieve such an understanding. As part of these reflection processes, the creation of a better balance plays a crucial role in regard to a successful family life (e.g., division of labour, education, caring for oneself and for other family members, time management, family life work balance). These processes can be understood as the act of staking out new horizons and possibilities in (family) life by re-evaluating everyday experiences and integrating new possibilities – within the framework of the socio-structural conditions.

It is crucial to link the results described to socio-pedagogical perspectives. Our research shows that single parents present a heterogeneous group with quite different family figurations. In a sample of 30 single parents, six different family figurations were identified. Furthermore, the respondents show five markedly different orientations. There is remarkable variance in the living situations and the web of interdependences of single parents even though they share the same orientation pattern, e.g., the parent-child-dyad orientation. In social work, it is important to consider (possible) members of family figurations not only as resources within daily life but also as powerful elements that must be taken into account. Thus, within the context of the (re)configuration of a family after divorce and dissolution, people suffer from different levels of loss, as regards power and autonomy while, at the same time, they are striving to (re)gain relative autonomy.

Regarding socio-pedagogical interventions, studies point out that neither the heterogeneity of the group of single parents nor the effects of power are well-reflected in the knowledge and interventions of professionals (Krüger 2016). However, a differentiated knowledge about family configurations, orientations and future perspectives is crucial for socio-pedagogical support, in order to match the needs of single parents. Our study suggests that differences between the current family figuration and the future family figuration, as well as the pattern of orientation, are crucial starting points when working with ‘single parents’. Parents can gain or keep control of their everyday family life by reflecting these patterns – and social work should develop methods to accompany these reflection processes. For example, systemic approaches to family counselling offer a methodological repertoire to deal with the heterogeneity of single parents in the course of counselling processes and interventions. It seems desirable to facilitate an exchange of knowledge and information between professionals and researchers on the results of family research. It would also be useful to develop networks so that practical social work can be more open to the variety of family configurations and the different orientation patterns of single mothers. Peer worker models, as they were established in Australia in the context of care leavers, might also be a good approach for interventions for single parents (Purtell et al. 2022). Peer worker models involve clients in the development of interventions. Before interventions are offered by social workers, they are reviewed and evaluated by single parents. The diversity of needs and heterogeneity of family constellations and perspectives can thus be incorporated into the planning and implementation of single parent interventions.

However, our study shows limitations. All in all, four perspectives emerge for further research:

1. There is still a big gap in the research on the orientation patterns of single fathers. To understand the development of family configurations, it would be necessary to take into account multiple perspectives and understand how they relate to one another, including those of both gender, children and – where relevant – social work professionals.

2. The question remains open as to what extent orientation patterns change and what conditions must prevail for this to happen. Are orientation patterns as changeable as family configurations? In our sample, we could see significant modifications of the orientation patterns in only two cases. Perhaps our study period was too short (16 months). Long-term studies would have had to be much longer in order to answer these questions.

3. It is interesting to note that the mothers we interviewed clearly favor the “multiple parenthood”. Because of our small sample, we cannot make any reliable statements as to whether or not (and why) the permanent establishment of a multiple parenthood model is difficult to achieve. There is a clear need for research in this area.

4. It should be noted that the interviews were conducted before the Corona crisis. It would be interesting to know how the remodeling of configurations took place, or is still taking place, during this time.

Overall, the study highlights the variety of family configurations after divorce and separation. It provides insights on the orientation patterns of mothers underlying their attempts to alter or maintain family configurations and family relations. From our point of view, it is an important task for social work to understand these orientation patterns and to provide means for parents after divorce and separation to reflect and eventually alter these orientations in order to gain a sense self-efficacy and control over the everyday family life.

References:

Arendell, T. (1996). Co-Parenting: A Review of Literature. Pennsylvania. Retrieved June 2021, from Eric: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED454975.pdf.

Beckmeyer, J. J., Coleman, M., & Ganong, L. H. (2014). Postdivorce Coparenting Typologies and Children’s Adjustment. Family Relations, 63 (4), 526-537.

Bohnsack, R. (2003). Rekonstruktive Sozialforschung: Einführung in qualitative Methoden. Opladen, Leske und Budrich.

Bohnsack, R. (2010). Documentary method and group discussions. In R. Bohnsack, N. Pfaff & W. Weller (Eds.), Qualitative analysis and documentary method in international educational research. (pp. 99-124). Opladen, Budrich.

Brighouse, H., & Swift, A. (2014). Family Values: The Ethics of Parent-Child Relationships, Princeton, Oxford: Princeton University Press.

Caroll, M. (2018). Gay Fathers on the Margins: Race, Class, Marital Status, and Pathway to Parenthood. Family Relations, 67 (1), 104-117.

Castrén, A.-M., & Ketokivi, K. (2015). Studying the Complex Dynamics of Family Relationships: A Figurational Approach, Retrieved June 2021, from Sociological Research Online: https://www.socresonline.org.uk/20/1/3/3.pdf

Castrén, A.-M. (2017). Rebuilding the Family: Continuity and Change in Family Membership and Relationship Closeness in Post-Separation Situations. In V. Česnuitytė, D. Lück & E.D Widmer (Eds.), Family Continuity and Change. Contemporary European Perspectives (pp. 165-186) London, Palgrave Macmillan Springer.

Castrén, A.-M. (2008). Post-Divorce Family Configurations. In E.D. Widmer, A.-M. Castrén, R. Jallinoja & K.Ketokivi (Eds.), Beyond the Nuclear Family: Families in a Configurational Perspective (pp. 233-253). Bern, Peter Lang.

Elias, N. (1971). Was ist Soziologie? Weinheim: Juventa.

Elias, N. (1976). Über den Prozess der Zivilisation. Soziogenetische und psychogenetische Untersuchungen. Frankfurt a. M.: Suhrkamp.

Elliott, S., Powell, R., & Brenton, J. (2015). Being a Good Mom: Low-Income. Black Single Mothers Negotiate Intensive Mothering. Journal of Family Issues, 36(3), 351-370.

Entleitner-Phleps, C., &Rost, H. (2017). Stieffamilien. In: Bergold, Pia/Buschner, Andrea/Mayer-Lewis, Birgit/Mühling, Tanja (Eds.): Familien mit multipler Elternschaft. Entstehungszusammenhänge, Herausforderungen und Potenziale (pp. 29-56). Opladen u.a.: Barbara Budrich.

Euteneuer, M., & Uhlendorff, U. (2014). Family concepts - a social pedagogic approach to understanding family development and working with families, European Journal of Social Work, 17(5), 702-717.

Euteneuer, M., & Uhlendorff, U. (2020). Familie und Familienalltag als Bildungsherausforderung. Weinheim, Basel: Beltz Juventa.

Fallesen P., & Gähler M. (2020). Post-Divorce Dual-Household Living Arrangements and Adolescent Wellbeing. In: Mortelmans D. (Eds.) Divorce in Europe. European Studies of Population, vol 21. Cham / CH: Springer.

Freistadt, J., & Strohschein, L. (2012). Family Structure Differences in Family Functioning: Interactive Effects of Social Capital and Family Structure. Journal of Family Issues, 34(7), 952-974.

Gahan, L. (2019). Separation and Post-Separation Parenting within Lesbian and Gay Co-parenting (GuildParented) Families. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Family Therapy, 40 (1), 98-113.

Goldberg, A.E., Moyer, A. M., Black, K., & Henry, A. (2014). Lesbian and Heterosexual Adoptive Mothers’ Experiences of Relationship Dissolution. Sex Roles, 73, 141-156.

Golombok, S., Zadeh, S., Imrie, S., Smith, V., & Freeman, T. (2016). Single Mothers by Choice: Mother-Child Relationships and Children´s Psychological Adjustment. Journal of Family Psychology, 30(4), 409-418.

Harris, H. L. (2013). Counseling Single-Parent Multiracial Families. The Family Journal: Counselling and Therapy for Couples and Families, 21(4), 386-395.

Jallinoja, R. (2008). Togetherness and being together. Family configurations in the making. In E.D. Widmer & R. Jallinoja (Eds.), Beyond the nuclear family: Families in a configurational perspective (pp. 97-118.). Bern, Peter Lang.

Kelle, U., & Kluge, S. (2010). Vom Einzelfall zum Typus. Fallvergleich und Fallkontrastierung in der qualitativen Sozialforschung. Springer VS: Wiesbaden.

Krüger, D. C. (2016). Alleinerziehende Migrantinnen. Lebenslagen und Fähigkeiten im Spannungsfeld von Abhängigkeit und Selbstbestimmung. Ibidem: Stuttgart

Lee, Y., & Hofferth, S. L. (2017). Gender Differences in Single Parents’ Living Arrangements and Child Care Time. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 26(12), 3439-3451.

Marchand-Reilly, J. F., & Yaure, R. G. (2019). The Role of Parents' Relationship Quality in Children's Behavior Problems. Journal of Child & Family Studies, 28(8), 2199-2208.

Nixon, E., Greene, S., & Hogan, D. (2015). “It’s What’s Normal for Me”: Children’s Experiences of Growing Up in a Continuously Single-Parent Household, Journal of Family Issues, 36(8), 1043-1061.

Oswell, D. (2013). The Agency of Children. From Family to Global Human Rights. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Phoenix, A. (2013). Social constructions of lone motherhood: a case of competing discourses. In S. E. Bortolaia (Eds.), Good Enough Mothering? Feminist Perspectives on Lone Motherhood (pp. 175-190) London, Routledge.

Poveda, D., Jociles, M. I., & Rivas, A. M. (2014). Socialization into single-parent-by-choice family life, Journal of Sociolinguistics, 18(3), 319-344.

Purtell, J., Bollinger, J. & Scott, B. (2022): Increasing Opportunities for Care Experienced Young People´s Participation in Decision-Making about State Care: Embedding Ethical Approaches in an Australien Context. In: Equit, C.& Purtell, J. (Eds.), Children's Rights to Participate in Out-of-Home Care: International Social Work Contexts , (pp. 30-49) London, New York: Routledge..

Quintaneiro, T. (2006) The concept of figuration or configuration in Norbert Elias' sociological theory. Retrieved June 2021, from Teoria & Sociedade 2006 (2): http://socialsciences.scielo.org/pdf/s_tsoc/v2nse/scs_a02.pdf.

Ryan, R. M., Claessens, A., & Markowitz, A. J. (2015). Associations Between Family Structure Change and Child Behavior Problems: The Moderating Effect of Family Income, Child Development, 86(1), 112-127.

Schneider, N. F., Krüger, D., Lasch, V., Limmer, R., & Matthias-Bleck, H. (2001). Alleinerziehen – Vielfalt und Dynamik einer Lebensform. Stuttgart, Berlin, Köln: Verlag Kohlhammer.

Schroeder, R. D., Osgood, A.K., & Oghia, M. J. (2010). Family Transitions and Juvenile Delinquency. Sociological Inquiry, 80(4), 579-604.

Smyth, L. (2017). The Creativity of Mothering: Intensity, Anxiety, and Normative Accountability. In V. Česnuitytė, D. Lück & E. D. Widmer (Eds.), Family Continuity and Change. Contemporary European Perspectives (pp. 269-290) London, Palgrave Macmillan.

Vascovics, L. A. (2009). Segmentierung der Elternrolle. In: Burkart, G. (Eds.), Zukunft der Familie. Prognosen und Szenarien (pp. 269-296). Opladen, Farmington Hills: Babara Budrich.

Walker, J., Crawford, K., & Taylor, F. (2008). Listening to children: gaining a perspective of the experiences of poverty and social exclusion from children and young people of single-parent families, Health and Social Care in the Community, 16(4), 429-436.

Walper, S., Entleitner-Phleps, C., & Langmeyer, A. N. (2020). Betreuungsmodelle in Trennungsfamilien: Ein Fokus auf das Wechselmodell, Zeitschrift für Soziologie der Erziehung & Sozialisation, 40(1), 62-80.

Widmer, E. D., Castrén, A.-M., Jallinoja, R., & Ketokivi, K. (2008). Introduction. In E.D. Widmer, A.-M Jallinoja & K. Ketokivi (Eds.), Beyond the Nuclear Family: Families in a Configurational Perspective (pp. 1-13). Bern: Peter Lang.

Zartler, U. (2014). How to Deal With Moral Tales: Constructions and Strategies of Single-Parent Families. Journal of Marriage and Family, 76(3), 604-619.

Author´s

Address:

Claudia Equit

Leuphana University Lueneburg

claudia.equit@leuphana.de

Author´s

Address:

Matthias Euteneuer

Fliedner Fachhochschule Düsseldorf, University of Applied Sciences

euteneuer@fliedner-fachhochschule.de

Author´s

Address:

Uwe Uhlendorff

Dortmund University

uwe.uhlendorff@tu-dortmund.de