Vulnerable

families in Ukraine as the main social service users: comparison of the

pre-pandemic and pandemic period

Introduction

In the

21st century, humanity faced a pandemic - COVID-19 which caused a collapse in

all spheres of society and economy and led to humanitarian, socio-economic, and

medical crises in the world (Thompson & Rasmussen, 2020). People had to

learn how to live in new conditions and fight with insidious disease. Many

countries closed their boundaries, declared lockdowns and other strict response

measures (Nay, 2020) to keep their citizens safe. All these heightened risk

factors are influencing already vulnerable populations, including families,

making their already rather difficult situations worse. Moreover, the system of

social protection of families and vulnerable families particularly also faced

new challenges. Social service providers had to adapt programs and meet the

evolving needs of all families during the pandemic. Ukraine is not the

exception. But there is one big difference between the world and Ukraine in

social work practice: the beginning of the pandemic in the world coincided with

the development of a new system of providing social services at the level of

territorial communities in Ukraine. So, this paper will 1) summarize the

existing approaches to “family” understanding and studies regarding the problem

of vulnerability of families and role of different factors causing family

vulnerability before the pandemic and at the beginning of it; 2) provide brief

analysis of Ukrainian system of social work with families, vulnerable families

started to be provided; 3) present data regarding vulnerability among families

in Ukraine in 2019 and in 2020, factors that caused vulnerability; 4) inform

about social service providers activity in turn to help vulnerable families to cope

with problems before and in the time of pandemic; and 4) provide

recommendations for government and local social agencies working with

vulnerable families how to make their work better.

1

Literature Review

1.1

Determination of

families and vulnerable families

Family is

regarded as a major social institution where individuals do their social

activity. It is “a unit of two or more people united by marriage, blood,

adoption, or consensual union, in general consulting a single household, interacting

and communicating with each other” (Desai, 1994). In the UNESCO report (1992),

family is characterized as “all people living in one household”. Moreover, even

if its members do not share a household because they are temporarily away,

family as a unit may exist as a social reality.

Despite

the different approaches towards defining the family in reviewed literature, it

is important to mention that we characterize family as microsociety created by

one or more person trying to construct an intimate environment, based on shared

goals, trust and accountability. In families people meet various needs

(physiological, emotional, etc.), provide support and sustenance, continuity

between past and future generations. Families force various functions such as:

differentiates regulation of sexual behavior,

reproduction, economic cooperation, education, affection, protection and

emotional support and social status (Anastasiu,

2012). But they changed drastically in recent years (Eneh,

Nnama-Okechukwu, …, & Okoye, 2017) mainly because

of industrialization and specialization of society.

The nature

and structure of the family has changed over the years too. For example, Park

(2013) differentiates three types of families: nuclear, joint

and three-generation ones. However, Oelze (2000)

points out nuclear, single, extended, childless, stepfamily and grandparent

types of families. The last classification of family types is closer to

Ukraine. In the works of Ukrainian researchers Kobylanska

(2017) and Kozachenko (2010) we can find provness of that. Moreover, Kobylanska

(2017) add so-called “distant families” that exists in Ukraine – families where

one of its members or more are far away for a long period because of work,

detention, or treatment.

Regardless

of type, all families can lead their own life, do routine tasks, cope with

stress, strength and conflicts, share and involve

resources, care about each other or children etc. However, sometimes families

get into difficult, stressful situations, which are beyond their control, and

as a result, they cannot cope with them and become inadequate or exhausted.

Certain social situations or life stages when individual or family need support

with social, health and economic (Vironkannas et al.,

2020) or material, social and emotional (Radcliff et al., 2012) problems are

defined as vulnerable. Situations when families’ needs cannot be met within

their own resources or their kith and kinship networks

have impact on families’ life are determined as vulnerability (Arney & Scott, 2011).

“Vulnerable

families” have a particular need for socially responsible, professionally

provided support, protection of children growing up within the family (Bauer,

& Wiezorek, 2016). In Ukraine it should be

provided at the territorial communities by creating and delivering of social

services vulnerable families need (Slozanska, Horishna, & Romanovska,

2020).

1.2

Factors that contribute

to family vulnerability

Vulnerable

families tend to suffer from high levels of stress and isolation resulting from

lack of support networks, financial or health problems, job-related

difficulties, or other negative factors that lead to emotional distress,

conflict, relational difficulty for family members, poor parenting

and ineffective communication (Task Force on the Family, 2003, p. 1542). To

factors that have negative influence on the families Slee

(2006) refers life changes, social inclusion, living environments, housing and

residential mobility, neighborhoods and social

cohesion, mental and emotional health, well-being, support for parenting,

childcare, service planning and provision, intersectional action (integrated

service delivery). “Chronic and multiple disadvantage,

stressful life events and children with ongoing physical, developmental,

emotional/behavior problems” can also cause problems

in families with which they cannot cope alone without external help and support

(Slee, 2006).

All

risk-factors families can face Gitterman (2014)

structured into two groups: 1) life conditions and 2) life circumstances and

events. While, Timshel,

Montgomery and Dalgaard (2017) differentiate

individual, family, societal and cultural levels of them.

Based on

the existing literature, that demonstrate different approaches to

identification and characterization of risk factors influencing family, we

grouped them into two blocks:

internal - mental or other disability, age, illness,

inability to take care or protect of oneself (Fawcett, 2009; Koeneke, Witt, & Oehme,

2015); absence of communication, interaction and emotional support (Chereni, 2017; Șoitu, 2015);

death, divorce, imprisonment, participation in hostilities, depression (Prasad,

Devi, Khasgiwala, & Vaswani, 2009; Van Hook,

2019); violence (Ribeiro et al., 2021) etc.;

external – natural disasters, radical social economic

and cultural changes, socially expected tasks and functions (Gomes, & Martinho, 2021), family disorganization, breaking

relationship, gender, stage of life, level of resources (Alston, Hazeleger, & Hargreaves, 2019; Berzin,

2010); interactions between individuals and social environments (Hollomotz, 2009); family size, poverty incidence (Orbeta Jr, 2005); risks, shocks, stress and isolation

(Lloyd, King, & Chenoweth, 2002; Terrion, 2006)

etc.

All

factors mentioned above can have short and long-term negative outcomes for

families. Long term perspective of being under the influence of risk factors

leads to stigmatization of vulnerable families (Vironkannas,

Liuski, & Kuronen,

2020). In time and even early support of families and early intervention,

assess to social services can have protective effect and prevent falling into

the category of vulnerable (Slozanska, 2018; Slozanska, Horishna, 2016;

Fawcett, 2009). Focus on the factor generating vulnerability among families is

in prerogative for social workers working with vulnerable families or

preventing vulnerability among families. The ranges of factors, which

individually or in combination can contribute to short or long-term

vulnerability, have to be identified and classified by

social worker before providing services in a local community where families

live (Slozanska, 2018). It is especially important in

time of the pandemic, when the cases of domestic abuse and family violence

increased dramatically (Usher, et al., 2020). Families also suffer from

economic stress, disaster-related instability, enhanced exposure to

exploitative relationships, and reduced options for support (Peterman et al.,

2020). Social isolation (van Gelder et al., 2020) starts to be the factor

causes the vulnerability among families.

At the

beginning of COVID-2019 Ukraine has just finished implementing of the first

stage of social welfare reform. Due to it social services have

to be provided at the territorial communities for people in need,

including vulnerable families by qualified social workers. Social service

providers have to be created in territorial

communities for that. So, the aim of the study is to examine factors causing

vulnerability among families in Ukraine before and in time of the pandemic and

what impact social services providers have on the families in territorial

communities to prevent or cope with vulnerability. Recommendations are proposed

to make social work with vulnerable families better.

2

Methods

Qualitative

secondary data analysis (QSDA) (Ruggiano, &

Perry, 2019) was used to conduct the research.

This study

used two sets of data: 1) a subset of findings from the larger annual study of

the Ministry of Social Politics of Ukraine; 2) a subset of findings from the

local annual studies of Regional Centers of Social

Services. The first and the second sets of data were collected in 2019 (before

the pandemic starts) and 2020 (in time of the pandemic). The researchers

conducting the QSDA were not involved in the parent studies. The official

requests were emailed to the Ministry and all Regional Centers

by the authors of this paper.

The data

received from the Ministry contained the information about the numbers of

social services providers in rural and urban territories in 2019, 2020; the

total numbers of social agencies’ clients during 2019-2020; and the list of

social services provided at the territorial communities in 2019, 2020.

The data

received from 20 Regional Centers of Social Services

(Kherson, Donetsk, Sumy, Poltava, Vinnytsia, Volyn, Dnipro, Dnipro, Zhytomyr,

Zakarpattia, Kyiv, Kirovohrad, Lviv, Mykolaiv, Rivne, Luhansk, Cherkasy,

Chernihiv, Chernivtsi, and Ternopil) of the 24 existing ones contained

information about types of clients (families) and factors that caused

vulnerability. This data were gathered by Regional Centers using standard reporting form № 12-soc, approved by

Ministry of Social Politics of Ukraine in 2017.

Research-question

approach in GSDA was used in writing secondary studies. The primary research

questions we wanted to answers on while analyzing received data were:

1.

What are the dynamics

of vulnerable families in 2019 and 2020 and do all of them receive social

services, what types of services?

2.

What are the factors

that caused vulnerability in families in Ukraine in 2019 and 2020 and what are

their main problems?

3.

Are there any dynamics

in creating of social services providers working with families in 2019 and 2020

in Ukraine?

These

primary research questions reflect the situation with social services providing

for vulnerable families and show the dynamics of increasing or decreasing

numbers of vulnerable families and factors which caused their vulnerability

before the pandemic time and in time of Covid-19 in Ukrainian context. It also

shows the dynamics of creating of social service providers ready to prevent

negative factors influencing the family and support vulnerable families who are

already suffer from some negative factors.

To find

answers on the research questions two sets of data were analyzed.

The researchers structure all data received from Regional Centers

in 20 excel files into one table. The data received from Ministry was used in

its primary form. The variables were generated before the data analysis.

All data

from parent study have been already coded before sending to researchers for

secondary analysis. IRB approval was obtained for the parent study.

Limitations

in the QSDA: 1) as no one from research team members were not included in the

parent study and had no influence on the primary analysis there is no strict

idea whether the data were collected correctly and in full; 2) authors conduct

the research with strict purpose using data that were collected for another

purpose – it limits a thematic finding that could be identified; 3) qualitative

secondary study conducting with data that were firstly collected and analyzed before can give changes in context and/or time

comparing with the data collected in present days.

3

Findings and Discussion

3.1

Family institutions in

Ukraine

Ukraine is

in the stage of actively applying a new approach to social welfare and social

work with families (Slozanska, 2020). A few laws

approved in 2016-2020 by the Ministry of Social Policy of Ukraine (On Social

Services, 2019; Methodical recommendations .., 2016;

Methodical recommendations.., 2017) forced the Amalgamated Territorial

Communities (ATCs), created due to the reform of decentralization

(Decentralization, 2021), to start their own local social agencies (Centers of social services providing (CSSP)) and finance

them from local budgets. In January 10, 2020, 1029

ATCs were in Ukraine (Ministry of Communities Territories Development of

Ukraine, 2020). Analysis of the Reports received from regions shows that in 2020

compared to 2019 the number of CSSP increased from 129 up to 205 (On approval

of the reporting form № 12-soc, 2017). It means that only 19,9% of ATCs full

fill the recommendation of the Ministry of Social Policy of Ukraine and started

CSSP. Definitely, in rural areas there is better

progress than in urban ones: the number of these institutions increased in

rural areas from 97 (in 2019) to 167 (in 2020) (see Table 1).

Qualified

direct practitioners hired in CSSP have to provide at

least minimum packet of based social services for families after assessing

their needs (Slozanska, 2020) immediately

(emergency), constantly, temporarily or one time as fast as possible (On Social

Services, 2019). Services can be provided at the clients’ residence, in the

premises of a social service provider (stationary or semi-stationary) or at the

place of stay (at home). Also governmental (state and

communal) and non-governmental (institutions, enterprises, associations,

charities, religious organizations, natural persons and individuals) agencies

can be involved in social service delivering integrated, interdisciplinary,

family-oriented approaches (Slozanska, 2017, p.

77-101). Case management has been recognized as a major way for social services

providing for families in need (On Social Services, 2019).

Starting

from 2020, the ATCs took responsibility for social services providing to all

citizens due to their needs and interests on the “one-stop-shop” (Slozanska, 2020). But to do that is very hard because the

small number of social workers, employed in CSSP in Ukraine - only 3,100 at the

beginning of 2021 (Ministry of Social Policy of Ukraine, 2021). At the same

time, it is very important to monitor and evaluate the quality of social

services provided by social agencies. This is the responsibility of the Regional divisions of the National Social Service of Ukraine

(2020) will be created in each region.

3.2

Vulnerable families in

Ukraine

In

Ukraine, the term “families in difficult life circumstances” (On Social

Services, 2019) is used to nominate vulnerable families. There we refer

families who have the highest risk of getting into difficult situations due to

the influence of external and/or internal factors that negatively affect their

life, health, development and functioning and which they cannot cope with on

their own (On Social Services, 2019). According to the data obtained in 2019,

there were 122,337 vulnerable families in the study areas. However, in in 2020,

the first year of COVID-19, the number of vulnerable families decreased and

became 108,139. The same negative dynamic we observed in social services

providing to vulnerable families. In 2019 386,846 vulnerable families were

covered by services in Ukraine, while in 2020 – 330,334 (On approval of the

reporting form № 12-soc, 2017).

We have to mention that in 2020 compering with 2019 the number

of CSSP in the territorial communities in Ukraine increased almost twice. But

it had no positive effect on quantitative growth of provision of social

services for vulnerable families in the places of their residence. It is

explained by the fact that at the beginning of the 2020 the CSSP did not work

in Ukraine as it was unable to comply with quarantine conditions. After being

vaccinated (at the 2-3 quarter of the year) employed social workers started to

work with families and provide services. Social agencies created in ATCs made a

richer menu of services to vulnerable families in the pandemic time too and

proposed new way to provide them.

In Ukraine

there is a little confuse with classification of vulnerable families. This

happened mainly because of 1) reforms that are still going on in social welfare

and social work and 2) fact that social work as professional sphere, education

and research is on the stage of developing in Ukraine. Therefore, there are

different approaches to differentiation of types of vulnerable families. In the

new law On Social Services approved in 2019 vulnerable families are structured

due to factors that cause vulnerability: aging; inability to take care of

oneself; illness; mental and behavioral disorders;

disability; homelessness; unemployment; poverty; behavioral

disorders in children; carelessness; i) loss of

social ties (including because of prisoning); child abuse; gender-based

violence; domestic violence; human trafficking; damage caused by fire, natural

disaster, catastrophe, hostilities, terrorist act, armed conflict, temporary

occupation (On Social Services, 2019). While, the

Procedure for identifying families (people) in difficult life circumstances

(2020) is another document that provides totally different classification of

vulnerable families.

Such a

variety of approaches to classification of vulnerable families is also among

scientists. Thus, Galaguzova (2000) differentiates

four types of families in difficult life circumstances (with children, with

people with disabilities, with alcohol or drugs problems, with internal

conflict). Rudyak (2020) proposes classification of

families in need very closed to that mentioned in the Procedure for identifying

families (people) in difficult life circumstances (2020).

At the

same time all CSSP still use documents approved before 2019. For example, all

data about number of vulnerable families, their types and factors that cause

vulnerability is collected through the annual filling of a form dated 2012 (On

approval of the reporting form № 12-soc, 2012). It provides the third type of

classification of families in difficult life circumstances, different from

those given in the law On Social Services (2019) and in the Procedure (2020).

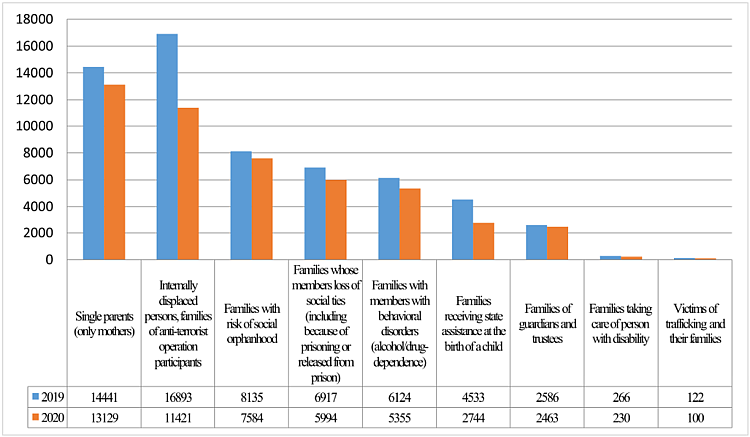

The

analysis with data received in the reports on 2019 and 2020 from 20 regions of

Ukraine (On approval of the reporting form № 12-soc, 2012) allowed us to define

the most typical types of families in difficult life circumstances. Among

families the number of which increased in 2020 compering with 2019 (see Fig. 1)

are: victims of domestic violence (on 0,8 % in 2020), families raising children

with disabilities and families with HIV status member (on 0,5 % in 2020 each),

aged people and migrant workers families (on 0,4 % in 2020 each). These types

of vulnerable families became clients of social workers not only in Ukraine.

The same tendencies were observed in the world too (Bordichuk,

2021; Khan et al., 2020; Usher et al., 2020). They were suffering of social

isolation (old ones) (Bordichuk, 2021), impossibility

to receive educational services (children with educational disabilities) Daftary et al., 2021) and due to the loss of external

connections (victims of domestic violence) (Usta, Murr, & El-Jarrah, 2021). Increasing in number of

migrants in 2020 is related to “open boundaries” for vaccinated Ukrainians.

Person living with HIV started to receive intensive, in-person and family-centered HIV primary care (Armbruster et al., 2020).

Almost the

same in both years were the number of families taking care of orphans, children

deprived parental care and Roma families. While in 2020, the number of foster

families tripled and the number of family type

orphaned increased to six. 191 children got services being in families of

guardians, trustees, foster families and family type orphaned in 2020. In 2019

there was no such child. This happened thanks to the reform of

deinstitutionalization, which was in an active phase of implementation in 2020

(Slozanska, Horishna,

2021).

Figure

1. Types of families in difficult life circumstances, the number of which

has increased in 2020, according to 2019

At the

same time analyzing the received data we observe the

decreasing in numbers of some types of families in 2020 comparing with 2019

(see Fig. 2). In Ukraine in 2020 became less the number of single parents (only

mothers) families, internally displaced families and families with

anti-terrorist operation participants, families with risk of social orphanhood,

families whose members lost social ties (including because of prisoning or

released from prison), families with members with behavioral

disorders (alcohol/drug-dependence), families receiving state assistance at the

birth of a child, families of guardians and trustees, families taking care with

disability and families whose members were victims of trafficking. But at the

same time transforming the got numbers into presents we saw that the number of

mentioned types of vulnerable families left almost the same in both years. The

exception is the percentage of internally displaced families and families with

anti-terrorist operation participants which number became less on 0,92 %. It

can be explained by the impossibility to move inside the country in the

pandemic time.

Figure

2. Types of families in difficult life circumstances, the number of which

has decreased in 2020, according to 2019

However,

the sent reports didn’t include information about other types of families in

difficult life circumstances mentioned in the law On Social Services (2019) and

the Procedure (2020). But the amount of each type of families is too small and

it is difficult to analyze. But,

there is no data about number of families with partial or complete loss of

physical activity, memory, unemployed, low-income or divorced families,

homelessness. This information is also interesting for analyses as many people

lost job in COVID-19 time, had huge troubles with health after being ill with

COVID, overlive emotional and psychological crisis, stayed alone.

It is

worse to mention that all these types of vulnerable families mentioned above

are characterized by low social status in any of the spheres of life,

impossibility to cope with the functions assigned to them and their adaptive

abilities are significantly reduced (Galaguzova,

2000, p. 76). However, each of it has its own unique dynamic, its strengths and weaknesses.

Due to the

law On Social Services (2019) and to the Procedure for identifying families

(people) in difficult life circumstances (2020), if a family faced at least one

of the above-mentioned factors and cannot cope with, it can be assumed that the

family is in difficult life circumstances. Social services in territorial

communities should be provided to support them.

The

analysis of the data given in the Reports from Ministry shows that in 2020,

compared to 2019, the number of families served during the year in the CSSP

increased from 52,157 to 64,407 (123.5% more than in the 2019) (see Table 1)

(On approval of the reporting form № 12-soc, 2012). At the same time, the

number of people served by the structural unit for the provision of social

services decreased slightly. These processes have been significantly influenced

by the decentralization reform that began in 2014 and aimed at forming

effective local self-government by optimizing local communities. As you can see

in the table 1.

Table 1.

Number of social services providers in ATCs.

|

Categories

|

Served

by a social service provider |

|||

|

Centers

of social services providing |

Structural

branch of the social services provider |

|||

|

2019 |

2020 |

2019 |

2020 |

|

|

Number of CSSP and their branches

during the reporting period |

129 |

205 |

99 |

90 |

|

Number of CSSP and their branches

in urban areas |

32 |

38 |

19 |

25 |

|

Number of CSSP and their branches

in rural areas |

97 |

167 |

80 |

75 |

|

Number of families (in person),

served during the reporting period |

52157 |

116564 |

11142 |

8514 |

|

Number of families (in person),

served during the reporting period in urban areas |

13365 |

33695 |

3021 |

2018 |

|

Number

of families (in person), served during the reporting period in rural areas |

38792 |

82869 |

8121 |

6496 |

As it is

seen from the table 1, the number of CSSP providing social services in ATCs for

vulnerable families increased in 22,7 % in 2020 comparing with 2019. As the

number of rural ATCs created in 2020 prevailed over rural ones, that logically,

that the number of CSSP in rural areas has increased significantly (on 35,1 %

in 2020). Number of vulnerable families, served during the reporting period in

CSSP also increased twice. And also CSSP placed in

rural areas served more clients too.

3.3

Problems encountered by

the vulnerable families in Ukraine

There was

no information about problems vulnerable families face in Ukraine in data

received from Ministry and Regional Centers. Based on

Oelze’s (2020) classification of family types, which

is close to our country, we analyzed papers on few

Ukrainian researchers (Heorhadze, 2019; Homenko, 2018; Kuzmenko, 2019;

Rybak, 2020; Sergienko, 2019; Sitnik,

2019; Slozanska, 2017; Tatarchuk,

2019; Yelagina, 2020) and structured typical

challenges of Ukrainian vulnerable families depending on family type:

· nuclear or

elementary families – consist of two parents and their children who are biological or

adopted – face many challenges and weaknesses, among which common are:

exclusiveness, which leads to isolation and stress, constant struggling with

conflict resolution, low income, neglecting of important things, etc.;

· single parent

families (increasing

in numbers during recent years in Ukraine (Voznyuk,

2021) – consist of one parent who either never has been married or has been

widowed/or divorced with one or more kids – to the cons of this family type can

be referred: low income, absence of possibility to work full-time, low quality

of childcare, inconsistency, especially if kids go back and forth between parents,

etc.;

· extended

family (“traditional”

family type in Ukraine) – consists of two or more adults (usually grandparents)

who are related through blood or marriage, usually along with children – to the weaknesses of such families referred: financial

problems, lack of privacy, conflicts, etc.;

· childless

family – units

who can't have, don't want to have or postpone having kids - to the weaknesses

of which are referred isolation, exclusiveness etc.;

· stepfamily – unit where two separate divorced

parents or one of them, with or without kids merge into one - in stepfamilies

children have the possibility to have two parents, but it also can create some

problems concerning growing up the children, solving problems, view on discipline;

· grandparent

family – unit

when one or more grandparent is raising their grandchild or grandchildren

because biological parents are not able properly to take care of their children

as they are abroad, in jail, on drugs, too young etc. – often have problems

with income, impossibility of grandparents to work full-time, have the health

and energy to rise children due to their needs.

Among main

problems of Ukrainian families in 2019 Georgadze

(2019, pp. 125-129) pointed out changing of family values, reluctance to have

(give birth) children, permanent stresses and

divorcing; Lazarenko and Kurova

(2019, p. 35), Skrypnyk and Pakushyna

(2019, pp. 389-391) - family conflicts, alcohol dependence of one or both

family members, financial difficulties, betrayal and jealousy; Mamrotska and Petrova (2018) - lack of own housing. In

COVID-19 times among main factors causing vulnerability Kalenyk

and Lysak (2020) point out poverty, Golina (2019) Katkova and Varina

(2020), Levadnya (2020), Palamarchuk

and Pedorych (2020), Prokopenko

(2020) - domestic violence. Moreover, the number of victims have

risen in COVID-times (Babkina, Tkachev,

& Danilchenko 2020; Chebanova

& Khlyvnyuk 2021; Timko 2020; Voznyuk

2021).

3.4

Services for vulnerable

families proposed in Ukraine

The law On

Social Services (2019) guarantees the basic social services providing to

vulnerable families due to their needs. Every year the Ministry of Social

Policy (MSP) and regional centers collect social and

economic data on social services delivery to families and individuals from all

regions of Ukraine (see Table 2). The MSP and regional centers

selected information about risk factors that are believed to adversely affect

families’ development or well-being. The received data is used to plan and do

state and regional programs of social services providing.

Table 2.

The title and number of social services provided to the vulnerable families in

2019-2020.

|

№ |

Basic social service due to the law On Social Services

(2019) |

2019 |

2020 |

|

1 |

Social support |

30243 |

27360 |

|

2 |

Consultancy |

315319 |

255803 |

|

3 |

Social prevention |

122500 |

106467 |

|

4 |

Social integration and reintegration |

16271 |

12609 |

|

5 |

Social adaptation |

41186 |

40650 |

|

6 |

Arrangement to family forms of care |

378 |

1032 |

|

7 |

Crisis and emergency intervention |

4088 |

4118 |

|

8 |

Representation of interests |

48476 |

42752 |

|

9 |

Mediation |

12195 |

9762 |

The number

of services provided by type increased in 2020 compared to 2019, except for

family placement / care and crises and emergency intervention services (Table

2). The most provided for the reporting period were counseling

and social prevention services.

3.5

Recommendations

So, the

number of vulnerable families in Ukraine before the COVID-19 and during the

pandemic time is high. In time of COVID-2019 the number of victims of domestic

violence, families raising children with disabilities, families with HIV status

member, aged people and migrant workers families increased significantly.

Factors that caused vulnerability in 2019 are different that those in 2020.

Poverty and domestic violence were dominant. Social services providers do all

the best to provide in time support and social services to all vulnerable

families. But, unfortunately, their work in COVID-19 times were not regular.

At the

same time, we noted some problematic moments. Due to the analyzed

data and current literature alignment, the research team developed the

following recommendations which are related not specifically to the COVID-19 time, but have some broader context. Their realization will

make the work with vulnerable families to productive/

Suggestions for government (The Ministry of Social Politics of Ukraine)

The

Ministry of Social Politics has a vital role and responsibility in the

development of high quality social services for

vulnerable families at local level. To make this process more understandable

during this time, the following ideas will support the developing of social

services for vulnerable families and help them to fight with the factors that

caused the risk.

· Align

regulatory framework. The analysis of regulatory acts in social

service providing shows the difference in differentiating of types of the

families in difficult life circumstances given particularly in the Laws (On

Social Services, 2019; the Procedure …2020) and in Report (On approval of the

reporting form № 12-soc, 2017). Moreover, the large annual study of The

Ministry of Social Politics of Ukraine and local annual studies of Regional Centers of Social Services which are prepared every year on

the demand of the Ministry of Social Policy contain data due to the Law On Social Services of 2003 which has expired when new Law

(2019) has come into force in 2020. But, not confusing, it is useful to bring

in compliance with all documentation and reporting requirements in accordance

with applicable laws.

· Develop a

Strategic Action Plan to Support Families in Difficult Life Circumstances. Nowadays it is important to build

and support a strict social services providing system

for families in difficult life circumstances at ATCs. Local Governments should

think about a Strategic Action Plan that should be developed based on a

qualitative assessment of community members' needs and with the input of

stakeholders from multiple sectors. As part of the Strategic Action Plan ensure

the social workers are main service providers for families and children in ATCs

who need the support and finance at the very beginning; clarify their actions

and timelines, measures of social services quality assessment. To make the Plan

fully implemented it is good to organize cooperation and coordination between

government, social agencies and citizens at ATCs to

provide a full spectrum of social services for families in difficult life

circumstances. The assessment, monitoring of social services provided at ATCs

and connection to them of community citizens is important too.

· Develop the

Early Intervention Service at ATCs. The families need to be identified for

additional support at the earliest sign of crises. It is important to organize

the network which members can mobilize and collaborate to support and help the

family in need. This will help to prevent a child from institualization.

Suggestions for Social Services Providers

In Ukraine

governmental and non-govermental (NGOs) organizations

play a vital role in supporting vulnerable families due to the law On Social

Services (2019). The new Law aims to introduce a new model of social services

providing which is based on creating a market for such services. This model

demands the improvement of the social services system’s management in the

context of decentralization and developing the unique approaches in its

organization at the local level (Semigina, 2020).

Local self-government in Ukraine has already started some new social agencies

to solve the existing locally social problems. However, the analysis of their

work shows that not all of them can provide demanding high quality social

services at the local level because of lack of:

government’s strict position in social support and welfare of vulnerable

families in Ukraine; understanding of the necessity of creating of social

agencies locally; knowledge and skills of already employed social workers to

full fill their roles in new conditions (Slozanska,

2017). In such a situation, social agencies providing social services at the

local level have to correspond to existing demands, be

nimble and proactive.

· Revise

Strategy. To

provide social services to vulnerable families social

agencies need to revise their strategies, developing them based on the good

assessment of citizens' demands, own and involved resources, constraints, possibilities

of cooperation and activities. Considering this as an opportunity for

innovation can help social agencies to identify effective solutions.

· Adapt

Approaches. Adapting social services providing approaches

to developed State Standards of Social Services Delivering (we have 17 of them

for each basic social service mentioned in the Law On

Social Service (2019)) is another important step to maintain effectiveness,

making them systematic. Being cyclical, continued and

flexible in providing social services of high quality for families in need at

ATCs, adaptive to changing conditions working with each individual and family

using remote methods to monitor and support them are also important challenges

social agencies have to cope with.

· Empower ATCs

and People. Communities

can care for families long-term, especially in situations when social agencies

are limited in resources and services they provide. Building strong networks

can help to create a framework to support families in need within the ATCs and

out of it. Active citizens can be good volunteers and good partners in helping

families at an early stage of getting into difficult life situations. Citizens

can serve as a liaison between local-government entities, social agencies and vulnerable families.

References:

(2019). Social work and disasters: A handbook for practice. Routledge.

(2012). The social functions

of the family. Euromentor Journal, 3(2), 1-7.

(2020). Addressing health inequities exacerbated by COVID-19 among youth

with HIV: expanding our toolkit. Journal of Adolescent Health, 67(2), 290-295.

(2020). Legal and forensic aspects of domestic violence in Ukraine. Ukrainian Journal of Medicine, Biology and Sports. 4(26): 336-342. DOI: 10.26693/jmbs05.04.336

(2016). "

Vulnerable families": reflections on a difficult category. CEPS Journal,

6(4), 11-28.

(2010). Vulnerability in the

transition to adulthood: Defining risk based on youth profiles. Children and

youth services review, 32(4), 487-495.

(2021). Loneliness and social

isolation of the elderly during the Covid-19 pandemic: factors that cause them.

Social work and education, 8(2).

(2021). The impact of the pandemic on domestic violence against

children. Available online: http://dspace.onu.edu.ua:8080/bitstream/

123456789/31042/1/45-47.pdf (accessed on 29 March 2021).

(2017). ‘You become two in

one’: Women’s representations of responsibility and emotional vulnerability in

Zimbabwean father-away families. International Social Work, 60(2), 366-378.

(2013). Effectiveness of early intervention programs for children with

mental disorders. Visnyk of Kharkiv National

University named after V. N. Karazin. Series: Psychology. 1046 (51), 184-186.

Available online: http://nbuv.gov.ua/UJRN/VKhIPC_2013_1046_51_42 (accessed on 29 March 2021).

(2021). Pivoting during a pandemic: School social work practice with

families during COVID-19. Children & Schools, 43(2), 71-78.

(2021). https://uareforms.org/en/reforms/Decentralization

(accessed on 20 June 2021).

(2017). Social work with families. In Okoye, U., Chukwu, N. & Agwu, P. (Eds.). Social work in Nigeria: Book of readings

(pp. 185–197). Nsukka: University of Nigeria Press Ltd

(2009). Vulnerability: Questioning the certainties in social work and

health. International social work, 52(4), 473-484.

(2000). Social pedagogy: a course of lectures. Moscow: Humanit. ed. VLADOS Center, 416.

(2014). Handbook of social work practice with vulnerable and resilient populations. Columbia University Press

Golina, V. V. (2019). Domestic violence: legal and criminological directions

and measures to prevent its manifestations in Ukraine. Available online: https://ivpz.kh.ua/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/%D0%97%D0%B1%D1%96%D1%80%D0%BD%D0%B8%D0%BA-%D0%BA%D1%80%D1%83%D0%B3%D0%BB%D0%B8%D0%B9-%D1%81%D1%82%D1%96%D0%BB-4.pdf#page=35

(accessed on 27 November 2020).

(2021). Social vulnerability as the intersection of tangible and

intangible variables: a proposal from an inductive approach. Revista Nacional de Administración,

12(2), e3773-e3773.

(2020). They are essential workers now, and should continue to be: Social workers and home

health care workers during COVID-19 and beyond. Journal of Gerontological

Social Work. 1–3. doi: 10.1080/01634372.2020.1779162.

(2019). The functioning of the family in the

condition of Ukrainian social policy. Youth and market 1, no. 168: 125-129. DOI: https://doi.org/10.24919/2308-4634.2019.158764

(2009). Beyond

‘vulnerability’: An ecological model approach to conceptualizing risk of sexual

violence against people with learning difficulties. British Journal of Social

Work, 39(1), 99-112.

Homenko, N. (2018). Unfunctioned family as a

psychological and pedagogical problem. Student scientific dimension of

socio-pedagogical problems present: a collection of materials of the II

International scientific and practical conference (April 26, 2018, Nizhyn) / For the general. ed. О. Lisovetc.

Nizhyn: NDU. M. Gogol: 82. Available online: http://www.ndu.edu.ua/storage/2018/zbirnuk_tez_2018.pdf#page=83

(accessed on 15 November 2020).

Kalenyk, O. P., & Lysak, N. P. (2020). Poverty as

a socio-psychological background to the development of the modern family: 28.

Available online: https://kneu.edu.ua/userfiles/fupstap/Tr_ta_N__26_02_2020.pdf#page=29

(accessed on 27 March 2021).

Katkova, T. A., & Varina, G. B. (2020). Psychological support for women

suffered from domestic violence. Conference Proceedings of the International

Scientific Online Conference Topical Issues of Society Development in the

Turbulence Conditions. The School of Economics and Management in Public

Administration in Bratislava. pp. 344-351. Available online: http://eprints.mdpu.org.ua/id/eprint/11213/1/Conference%20Proceedings_VSEMvs_30.5.2020-344-351-2-8.pdf

(accessed on 29 March 2021).

(2020). Service providers' perceptions of families caring for children

with disabilities in resource‐poor settings in South Africa. Child & Family

Social Work, 25(4), 823-831.

(2018). Typology of families

on various grounds. Collection of scientific works of Uman

State Pedagogical University named after Pavel Tychyna,

(2), 131-142.

(2015). HDAC family members

intertwined in the regulation of autophagy: a druggable vulnerability in

aggressive tumor entities. Cells, 4(2), 135-168.

(2010). Modern Ukrainian multigenerational family: decline or prosperity?. Bulletin of Lviv University. Sociological

Series, (4), 246-253.

(2021). Relevance and social

significance of the problem of conflicts between young couples. Education and

science, (1).

(2019). New models of

parenthood: factors, trends, characteristics. Current problems of sociology,

psychology, pedagogy, 40 (1-2). Available online:

http://apspp.soc.univ.kiev.ua/index.php/home/article/viewFile/877/750 (accessed

on 15 November 2020).

Lazarenko, A. H., & Kurova, A.A. (2019). Divorse as one of the problems of modern society. Editorial

Board: 35. Available online: http://repository.sspu.sumy.ua/bitstream/123456789/7303/1/%D0%A2%D0%BE%D0%BC-2.pdf#page=35

(accessed on 27 November 2020).

(2020). Psychological violence

as a kind of relationship in the family. Available online:

https://ela.kpi.ua/bitstream/123456789/39762/1/S_r_i_s_X_2020-113-115.pdf

(accessed on 29 March 2021).

(2002). Social work, stress and burnout: A review. Journal of mental health,

11(3), 255-265.

(2018). Student family: problems and

prospects. Available online: https://cardfile.onaft.edu.ua/bitstream/123456789/9364/1/Ekonom_ta_sots_aspekty%20rozv_2018_Mamrotska.pdf

(accessed on 27 November 2020).

Methodical recommendations for

the implementation of the united territorial community (self-governing) powers

in the sphere of social protection of the community members. (2016a). Ukraine:

Government Publications. Available online:

http://www.mlsp.gov.ua/labour/control/uk/publish/article?art_id=186204&cat_id=107177.

(accessed on 01 September 2019).

Methodical recommendations for

the organization of social services order. (2016b). Ukraine: Government

Publications. Available online: http://www.mlsp.gov.ua/labour/control/uk/publish/article.

(accessed on 01 September 2019).

Ministry of Communities

Territories Development of Ukraine. (2020). Available online: https://www.minregion.gov.ua/press/news/shho-u-rozvitku-gromad-i-teritoriy-vidbulosya-za-2019-rik-dani-monitoringu-detsentralizatsiyi/

(accessed on 01 March 2022).

Ministry of Social Policy.

(2017). On approval of the reporting form № 12-soc (annual) "Report on the

organization of social services" and instructions for its completion (from

30.01.2017 № 138). Available online: https://zakon.rada.gov.ua/laws/show/z0251-17#Text

(accessed on 01 March 2021).

(2020). Can a virus undermine human rights? The

Lancet Public Health. 5: E238–e239. doi:

10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30092-X.

(2018). Implementation of the

early intervention system in Ukraine. Education of people with special needs:

ways of development.1, no. 14, 134-139.

Novytska, I. (2020). The impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on the level of

domestic violence in Ukraine and the world. Available online: http://elar.naiau.kiev.ua/bitstream/123456789/19159/1/%D0%97%D0%91%D0%86%D0%A0%D0%9D%D0%98%D0%9A%2014.12.2020_p134-137.pdf

(accessed on 29 March 2021).

(2020). There are 6 different

family types and each one has a unique family dynamic. Available online:

https://www.betterhelp.com/advice/family/there-are-6-different-family-types-and-each-one-has-a-unique-family-dynamic/

(accessed on 15 March 2021).

On Social Services (Ukraine) 17.01.2019,

No 2671-VIII. Available online: https://zakon.rada.gov.ua/laws/show/2671-19

(accessed on 01 Febuary 2020)

(2005). Poverty, vulnerability and family size: evidence from the

Philippines. Poverty strategies in Asia, 171.

(2020). Domestic violence as a

socio-pedagogical problem. Scientific Bulletin of the North. Series: Education.

Social and behavioral sciences: a scientific journal / Academy of the State

Penitentiary Service. Chernihiv: DPtS Academy, 1 (4),

85. DOI 10.32755/sjeducation.2020.01.085

(2021). Park's text book of preventive and social medicine. Edition: 26th.

Publisher: Banarsidas Bhanot

Publishers.

(2020). Pandemics

and Violence Against Women and Children. Center for Global Development Working

Paper. 528.

(2009). Families in difficult situations. Indian Journal of Social Work.

70.2, 191-218.

(2020). Available online: https://zakon.rada.gov.ua/laws/show/587-2020-%D0%BF#Text

(accessed on 21 March 2021).

(2020). Combating domestic

violence in the mechanism of protection of human and civil rights and freedoms.

(2012). Association between family composition and the well-being of

vulnerable children in Nairobi, Kenya. Maternal and Child Health Journal,

16(6), 1232-1240.

(2021). Vulnerability, family violence and

institutionalization: narratives for elderly and professionals in social welcome

center. Revista gaúcha de enfermagem, 42.

(2020). Classification of

persons who find themselves in difficult life circumstances. Current issues of

state and law, (86), 197-203.

(2019). Conducting

secondary analysis of qualitative data: Should we, can we, and how?. Qualitative Social Work, 18(1), 81-97.

Rybak, V. (2020). The Social

and Psychological Factors of Conflicts in the Family. (Master’s thesis). Herson. HDU: 85. Available online: http://ekhsuir.kspu.edu/handle/123456789/12730

(accessed on 15 November 2020).

(2020). Local Self-Government

Transformations in Ukraine and Reforms of Social Services: Expectations and

Challenges. Traektoriâ Nauki,

6(01), 1001-1006.

Sergienko, M. (2019). Social work with young families in the period of adaptation

to married life. (Master’s thesis): 97. Available online: https://ir.stu.cn.ua/handle/123456789/19129

(accessed on 15 November 2020).

Shatska, M. (2019). The family as a small social group and social institution.

Scientific developments of youth at the present stage. Kyiv National University

of Technology and Design, 525-526. Available online: https://er.knutd.edu.ua/bitstream/123456789/14261/3/NRMSE2019_V3_P525-526.pdf

(accessed on 15 November 2020).

(2019).

Support for large families as a priority of the state family policy. State

building 1. DOI: https://doi.org/10.34213/db.19.01.15

(2015). RESILIENCE AND

VULNERABILITY: COMPETING SOCIAL PARADIGMS?. Scientific

Annals of the “Alexandru Ioan

Cuza” University, Iaşi. New

Series SOCIOLOGY AND SOCIAL WORK Section, 8(1).

Skrypnyk, M. A., & Pakushyna, L. Z. (2019).

General characteristics of divorce as a social phenomenon: the dynamics of

divorce. Actual problems of natural and human sciences in researches

of young scientists “Raisin-2019” / XXI All-Ukrainian scientific conference of

young scientists, 389-391. Available online: http://eprints.cdu.edu.ua/3643/1/rodzinka_2019%20-389-391.pdf

(accessed on 27 November 2020).

Slee, Phillip T. (2006). Families at risk: the effects of chronic and

multiple disadvantage. Shannon Research Press.

Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/272727914_Families_at_Risk

(accessed on 25 November 2020).

Slozanska, H. (2017). Social protection of the population in the conditions of

the united territorial community. Ministry of education and science of Ukraine,

M.Dragomanov national

pedagogical university, 205. Available online:

https://www.researchgate.net/profile/HannaSlozanska/publication/315976888_Socialnij_zahist_naselenna_v_umovah_ob%27ednanoi_teritorialnoi_gromadi/links/58ed30b70f7e9b37ed14d88e/Socialnij-zahist-naselenna-v-umovah-obednanoi-teritorialnoi-gromadi.pdf#page=205

(accessed on 15 November 2020).

(2017). Are current state

social agencies able to provide social services to the population at the ATCs

effectively: selected study. Social work and education, 4(2), 77-101.

(2017). Social services: are

current state social agencies ready to provide them on the level of local

communities in Ukraine (selective survey). Social work and education. 4 (2),

77-101.

(2018). Social work in the

territorial community: theories, models and methods:

monograph. Ternopil: TNPU them. V. Hnatyuk, 382 p.

(2016). The activity of social workers on the provision of social

services to the population in the territorial community. Collection of

scientific works of Khmelnitsky Institute of Social Technologies of the

University of Ukraine, (12), 113-118.

Slozanska, H., Horishna, N., and Romanovska, L. (2020). Community

Social Work in Ukraine: towards the Development of New Practice Models. Socialinė teorija, empirija, politika ir praktika. 20, 53-66.

Some issues of the National

Social Service of Ukraine: Resolution of the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine; List,

Regulations of 26.08.2020 № 783. Database "Legislation of Ukraine". Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine. Available online: https://zakon.rada.gov.ua/go/783-2020-%D0%BF

(accessed on 19 March 2021).

(2001). Understanding families

in India: A reflection of societal changes. Psicologia:

Teoria e Pesquisa, 17, 177–86.

(2017). Ukraine: Government Publications. Available online:

http://www.msp.gov.ua/timeline/Decentralizaciya-vladi-.html. (accessed on 19 March 2021).

(2003). Family pediatrics: Report of the Task Force on the Family.

Pediatrics, 111(6), 1541-1571.

Tatarchuk, А. (2019). Features of social work with children from distant

families. (Master’s thesis): 85. Available online: http://ir.stu.cn.ua/handle/123456789/19114

(accessed on 15 November 2020).

(2006). Building social

capital in vulnerable families: Success markers of a school-based intervention

program. Youth & Society, 38(2), 155-176.

(2020). What does the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) mean for

families? JAMA Pediatrics. doi:

10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.0828.

(2020). Domestic violence in the context of the

COVID-19 coronavirus pandemic in Ukraine. (2020). Available

online:

http://ekmair.ukma.edu.ua/bitstream/handle/123456789/18704/Tymko_Domashnie_nasylstvo_v_umovakh_pandemii_koronavirusu_COVID-19_v_Ukraini.pdf?sequence=1

(accessed on 29 March 2021).

(2017). A systematic review of risk and protective factors associated

with family related violence in refugee families. Child abuse & neglect,

70, 315-330.

(1992). Bangkok, Thailand: Bangkok, Thailand:

UNESCO.

(2020). Family violence and COVID‐19: Increased

vulnerability and reduced options for support. Int J Ment

Health Nurse, 549-552.

(2021). COVID-19 Lockdown and the increased violence against women:

understanding domestic violence during a pandemic. Violence and gender, 8(3),

133-139.

(2020). COVID-19: Reducing

the risk of infection might increase the risk of intimate partner violence. EClinical Medicine. doi:

10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100348.

(2019). Social work practice with families: A resiliency-based approach.

Oxford University Press, USA.

(2020). The

contested concept of vulnerability: a literature review. European Journal of

Social Work, 23(2), 327-339. https://doi.org/10.1080/ 13691457. 2018.1508001

Voznyuk, T. (2021). Exacerbation of the problem of domestic violence in a

Pandemic. Recommended for publication by the Academic Council of Zhytomyr State

University named after Ivan Franko (Minutes № 3 of March 26, 2021): 57.

Available online: http://eprints.zu.edu.ua/32400/1/%D0%B7%D0%B1%D1%96%D1%80%D0%BD%D0%B8%D0%BA%20%D0%9B%D1%96%D1%82%D0%BE%D0%BF%D0%B8%D1%81%D0%B5%D1%86%D1%8C%2016.pdf

(accessed on 29 March 2021).

(2020). Systematic review of

community- and home-based interventions to support parenting and reduce risk of

child maltreatment among families with substance-exposed newborns. Child

Maltreatment. 25(2), 137–151. doi:

10.1177/1077559519866272.

Yelagina, M. (2020). The main factors of problems in the modern Ukrainian

family. Social work and modernity: theory and practice of professional and

personal development of a social worker: materials of the Tenth International

scientific-practical conference (December 18, 2020, Kyiv). KPI. Igor Sikorsky,

FSP, CF. Kyiv: Lira-K: 66–69. Available online: https://ela.kpi.ua/bitstream/123456789/39168/1/S_r_i_s_X_2020-66-69.pdf

(accessed on 20 March 2021).

:

Anna Slozanska

Ternopil Volodymyr Hnatyuk National Pedagogical

University

Ternopil, Ukraine

+380971838135

annaslozanska@gmail.com

:

Svitlana Stelmakh

Department of Pedagogics and Social Work

HEI Ukrainian Catholic University

Lviv, Ukraine

pedagog@ucu.edu.ua

:

Iryna Krynytska

Department of Pedagogics and Social Work

HEI Ukrainian Catholic University

Lviv, Ukraine

krynytska@ucu.edu.ua