Semiotic Analysis in the Study of Social Work

1

Research and professional practices have the joint aim of re-structuring the preconceived notions of reality. They both want to gain the understanding about social reality. Social workers use their professional competence in order to grasp the reality of their clients, while researchers’ pursuit is to open the secrecies of the research material. Development and research are now so intertwined and inherent in almost all professional practices that making distinctions between practising, developing and researching has become difficult and in many aspects irrelevant. Moving towards research-based practices is possible and it is easily applied within the framework of the qualitative research approach (Dominelli 2005, 235; Humphries 2005, 280).

Social work can be understood as acts and speech acts crisscrossing between social workers and clients. When trying to catch the verbal and non-verbal hints of each others’ behaviour, the actors have to do a lot of interpretations in a more or less uncertain mental landscape. Our point of departure is the idea that the study of social work practices requires tools which effectively reveal the internal complexity of social work (see, for example, Adams & Dominelli & Payne 2005, 294 – 295).

The boom of qualitative research methodologies in recent decades is associated with much profound the rupture in humanities, which is called the linguistic turn (Rorty 1967). The idea that language is not transparently mediating our perceptions and thoughts about reality, but on the contrary it constitutes it was new and even confusing to many social scientists. Nowadays we have got used to read research reports which have applied different branches of discursive analyses or narratologic or semiotic approaches. Although differences are sophisticated between those orientations they share the idea of the predominance of language.

Despite the lively research work of today’s social work and the research-minded atmosphere of social work practice, semiotics has rarely applied in social work research. However, social work as a communicative practice concerns symbols, metaphors and all kinds of the representative structures of language. Those items are at the core of semiotics, the science of signs, and the science which examines people using signs in their mutual interaction and their endeavours to make the sense of the world they live in, their semiosis.

When thinking of the practice of social work and doing the research of it, a number of interpretational levels ought to be passed before reaching the research phase in social work. First of all, social workers have to interpret their clients’ situations, which will be recorded in the files. In some very rare cases those past situations will be reflected in discussions or perhaps interviews or put under the scrutiny of some researcher in the future. Each and every new observation adds its own flavour to the mixture of meanings. Social workers have combined their observations with previous experience and professional knowledge, furthermore, the situation on hand also influences the reactions. In addition, the interpretations made by social workers over the course of their daily working routines are never limited to being part of the personal process of the social worker, but are also always inherently cultural. The work aiming at social change is defined by the presence of an initial situation, a specific goal, and the means and ways of achieving it, which are – or which should be – agreed upon by the social worker and the client in situation which is unique and at the same time socially-driven.

Because of the inherent plot-based nature of social work, the practices related to it can be analysed as stories (see Dominelli 2005, 234), given, of course, that they are signifying and told by someone. The research of the practices is concentrating on impressions, perceptions, judgements, accounts, documents etc. All these multifarious elements can be scrutinized as textual corpora, but not whatever textual material. In semiotic analysis, the material studied is characterised as verbal or textual and loaded with meanings.

We present a contribution of research methodology, semiotic analysis, which has to our mind at least implicitly references to the social work practices. Our examples of semiotic interpretation have been picked up from our dissertations (Laine 2005; Saurama 2002). The data are official documents from the archives of a child welfare agency and transcriptions of the interviews of shelter employees. These data can be defined as stories told by the social workers of what they have seen and felt. The official documents present only fragmentations and they are often written in passive form. (Saurama 2002, 70.) The interviews carried out in the shelters can be described as stories where the narrators are more familiar and known. The material is characterised by the interaction between the interviewer and interviewee. The levels of the story and the telling of the story become apparent when interviews or documents are examined with the use of semiotic tools.

The roots of semiotic interpretation can be found in three different branches; the American pragmatism, Saussurean linguistics in Paris and the so called formalism in Moscow and Tartu; however in this paper we are engaged with the so called Parisian School of semiology which prominent figure was A. J. Greimas. The Finnish sociologists Pekka Sulkunen and Jukka Törrönen (1997a; 1997b) have further developed the ideas of Greimas in their studies on socio-semiotics, and we lean on their ideas.

In semiotics social reality is conceived as a relationship between subjects, observations, and interpretations and it is seen mediated by natural language which is the most common sign system among human beings (Mounin 1985; de Saussure 2006; Sebeok 1986). Signification is an act of associating an abstract context (signified) to some physical instrument (signifier). These two elements together form the basic concept, the “sign”, which never constitutes any kind of meaning alone. The meaning will be comprised in a distinction process where signs are being related to other signs. In this chain of signs, the meaning becomes diverged from reality. (Greimas 1980, 28; Potter 1996, 70; de Saussure 2006, 46-48.)

One interpretative tool is to think of speech as a surface under which deep structures – i.e. values and norms – exist (Greimas & Courtes 1982; Greimas 1987). To our mind semiotics is very much about playing with two different levels of text: the syntagmatic surface which is more or less faithful to the grammar, and the paradigmatic, semantic structure of values and norms hidden in the deeper meanings of interpretations. Semiotic analysis deals precisely with the level of meaning which exists under the surface, but the only way to reach those meanings is through the textual level, the written or spoken text. That is why the tools are needed. In our studies, we have used the semiotic square and the actant analysis. The former is based on the distinctions and the categorisations of meanings, and the latter on opening the plotting of narratives in order to reach the value structures.

2 The semiotic square emphasizes the diversity of meaning

Semiotic squares can be used as an analytic tool in the research where the meaning structures are built on the basis of the relationships of concepts. Very often the researcher recognizes that the transcribed text includes conceptual pairs, which are binding together in someway. The semiotic square is a means of analysing paired concepts more fully, because it shows the relationships of signs. The possibilities for signification in a semiotic system are richer than the simple either/or of binary logic (Chandler 2002, 118), while the meaning is not understood as something which is not coherent instead include diversity.

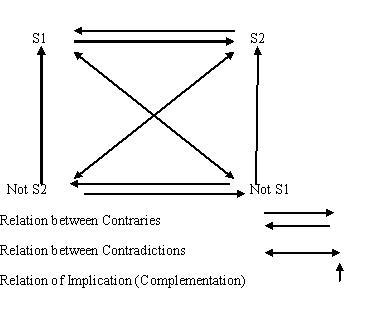

The semiotic square visualises the semantic categories (Greimas & Courtes 1982, 308–309; see also de Saussure 2006, 161–163). They are not detectable from the surface of the text, but they are interpreted by the researcher from the semantic analysis of the whole episode. Semiotic square is comprised of opposing (contraries), contradictory and complementary relationships. In Figure 1, the upper corners of a square an opposition (S1/S2) could be marked as black (S1) and white (S2), for example (Chandler 2002, 118-120). The lower corners represent the contradictions of upper ones. The contradiction (S1/not S1) of black is non-black (not S1) and the contradiction of white is non-white (not S2). The contradictory components of the semiotic square are mutually exclusive and cancel each other out (Greimas & Courtes 1982, 60–61, 309). That means that the position, which is not white is not necessarily black. The third relationship in the semiotic square is complementary (not S2/S1). Something which is not black could become white.

Figure 1: The semiotic square

Excerpt 1

Interviewer: If you were asked to expand on your expert knowledge. How would you characterise your expertise?

Interviewee: I’m an expert in dealing with people who have experienced domestic violence; at working through it with them and helping them to deal with their own experiences of it, as well as possibly also helping them to think about how to move forward in their lives. I help them think through the survival process in a number of different ways. I give the women a kind of women’s moment. There are so many ways of thinking about and seeing their own [being victimised], that the experience of being a victim is in this body and how she [survives], relaxation and various forms of mental exercises and all sorts of physical things, from massage and stretching to putting on make-up. And I think that [survival] somehow begins with just improving one’s self-esteem. The first step might be that we do a facial here, which might make some [client] feel like she is still a human being, that there is still something left of her […]

Excerpt 2

Interviewee: I might describe the goal of my work as helping [the client] gain control of her own life. So whether she ends up getting divorced or continues in the relationship is actually irrelevant – the main thing is that she is able to gain control of her own life, so it’s not under someone else’s control […]

Then we do aftercare, which is when the [women] come and visit us after a year and we get to see how they have really recovered. They look completely different. They’ve started to take care of themselves. They know what they want. They’ve got their friends back. They’ve taken up hobbies, got jobs or what have you. Whatever – the point is that they have taken control of their own lives, and then when you think back at when they first came here, what they were like, completely oppressed – they had abandoned themselves and who they are.

The social worker renders the victim and survivor an opposing pair. This categorisation includes the seed of the subjectivity of a survivor, which are both the current moment and the intended goal for the women. The victim and survivor are indeed opposed to one another, although they are not mutually exclusive. A woman cannot even become a client if she is a complete and total victim of domestic violence and the situation she is in. Similarly, a woman who can only be described as a survivor might not even require support in her life. The victim and survivor have many things in common. A woman survives a violent situation by using the resources she has.

In Figure 2, inability and self-esteem are sub-opposing concepts. Social workers are able to refer to women as oppressed and having abandoned themselves as opposed to referring to them as incapable. Self-esteem and being a victim are mutually exclusive, as are inability and survival. Taking control of one’s life is not to be a victim and, conversely, rejecting oneself conflicts with the concept of being a survivor. The complementary relationship between self-esteem and the subjectivity of the survivor is extremely important. Self-esteem implies survival. It is related to taking control of one’s life, which conflicts with being a victim. Being oppressed implies being a victim, in which case change is impossible.

Figure 2: Social workers’ characterisation of female clients and the changes they experience.

A woman’s inability to control her own life or make decisions for herself leads her to remain in an oppressive relationship. This inability may be physically and bodily debilitating, but it is also indicative of emotional submission. The complimentary relationship between self-esteem and being a survivor illustrates the action taken by women aimed at achieving autonomy. The right side of the figure (inability-victim) are indicative of nature while the left side (self-esteem-survivor) represents culture. The image of the female client can thus be culminated in the image of a survivor, alongside which lies the image of the social worker as a survivor. It might also be a type of narration creating not only the possibility for the clients themselves to go on, but also allowing the social workers to continue their work. In reality, the lives of female clients are like rollercoaster – they go up and down, forward and backwards – just as we all have good and bad days in our working lives.

The nature-culture distinction can be detected in the excerpts from the material. When viewed against the backdrop of this dichotomy, two distinct images of women appear. In one, the woman is a victim and helpless, she is subordinate and easy to control, i.e. at the mercy of nature and without her own will. In this phase of the social work process, providing women with the support they need involves not only talking with them but also having a more comprehensive bodily impact. Increasing the client’s sense of control allows her to take on the role of an autonomous woman and survivor subject who is able to make rational decisions. Then, a woman’s actions become motivated by cultural choices and active doing, as opposed to just existing in the world.

From the perspective of the assignment of meaning, the distinction between nature and culture is crucial (Levi-Strauss 1987, 40–45), as it is through this distinction that the narrator classifies and clarifies his or her own conceptions. In spoken and written discourse, nature appears as free, unstructured, undefined and uncontrollable. Culture, on the other hand, appears as organised, developed and one step ahead of nature. The distinction between nature and culture can serve as a tool in both the organisation and categorisation and the search for the foundations of meaning in textual material. The applicability of the nature - culture distinction is based on the notion that knowledge is conscious of itself and that fact that it cannot be extended to all areas of reality or all areas of life (Sulkunen 1997, 50). In other words, the speaker and/or writer of a story produce and convey certain meanings of which he or she is not necessarily actively aware.

The social worker classifies the nature of his or her work in relation to the tension-conflict scale depicted in Figure 2, in which social workers work side-by-side with their clients. Professionals in the field have a great deal of knowledge about the relationship with violent cohabitant and the phases women living in them go through. Change is depicted as being and doing, in that order. The female client’s active role is developed to help her find and become herself. When studying spoken discourse, we should pay attention not only to what is said but also to what is left unspoken. Parenting is not included in the aforementioned interview excerpts. Despite the fact that the majority of the shelter’s clients are mothers and that the social workers observe the interaction between mothers and their children on a daily basis, the social workers do not make any reference to the women finding themselves as mothers. According to professionals in the field, freeing oneself from a relationship or creating changes within it can only begin once the woman has found herself. Removing herself from the relationship of a violent cohabitant is one of many options available to a woman in this situation. We can also infer from the material that motherhood follows once a woman is able to take care of her own wellbeing. A good mother is a mother who takes care of herself as a woman.

3 Actant analysis reveals values beneath

Actant analysis is another means of doing semiotic research which is developed by Greimas (1966/1980) and described in this context. Actant model can be used for instance to examine the hidden values of our actions. The material or the data we are studying has to be conceived as narratives. Greimas as a narratologist has proposed that in his model of the canonical narrative schema there have to be a continuant subject and temporal change of which it depicts (Prince 1988; 58; ref. Törrönen 2000, 82). In an ideal narrative there is a plot which can be made visible and able to analyse by the actant model.

In the actant model, the individual units, actants, are general relationship categories, of which the most important is that between the subject and the object (Greimas 1980, 205 – 206). The other actants, anti-subject, opponent, sender, helper and receiver, are built around them. Actants are not actors per se, but rather positions or roles, which can be changed. Actants can also be ideologies or institutions or whatever non-human things. This is important to keep in mind when referring to the actors in actantial analyses. A single actor may appear in a number of different actant positions over the course of a story, which allows us to follow changes such as “the development of identity” over the course of analysis. The actantial model highlights positional oppositions and conflicting aims. Each and every actant has certain aims and goals, which it/he/she aims to achieve (Greimas & Courtes 1982, 207). The actantial model can be used as an analytical tool or as an outcome of analysis.

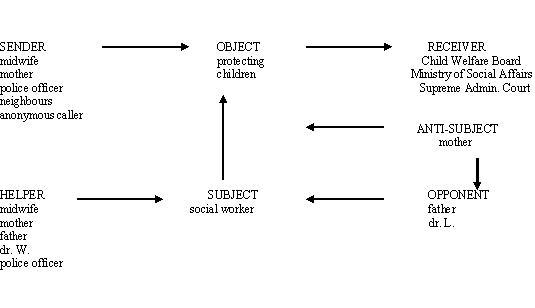

Figure 3: The actantial model

Greimas (1980, 205-206) has proposed that the apparent simplicity of the actant model increases its operational value. Its simplicity is based on the structure of a theatrical performance where a subject aims at acquiring a particular value object. Its/his/her intentions reflect the anti-subject and the helper, as well as the helper of the anti-subject, the opponent. The actions of the subject are also regulated by the sender and the receiver, which in turn motivate and gratify the subject. The flow of the narrative illustrates the subject’s attempt at engaging the object, which also leads to the inversion toward the anti-subject and to the battle of competing wills. (Saurama 2002, 72-73.)

Social work is full of narrative cases where aims and values contradict each other. Particularly in child protection cases the situations are often very multidimensional, difficult and messy. We have used the actant model in studying child protection cases where social workers as subjects try to save the child and/or protect her/his safety. The cases where the children have for instance to be taken into care without the parental consent, suit very well in the analysis of competing wills.

The better the case is documented the easier it is to follow the narrative schema of the case. The analysis starts from finding out all the actors in the case. Who is the initiator or informer of the child at risk or danger? How the social worker as the subject of the story starts her/his endeavour? Who will help her/him? Who might resist the actions, etc? By examining the motives of each particular actor and by positioning them in their actant roles, the researcher can follow the shifts taken. It is not only a question of actions which are at the focus of the analysis, but the value-structures motivating the actors.

We have selected the case of a mother suffering from mental health problems and her attempt to cope with an alcoholic husband and two small children. The case is old and so it illuminates the measures and values of the past social work. The social worker has documented her visits and actions to have been taken in the course of time. The concrete goal of the social worker-subject was to have the family’s children either temporarily or permanently taken into care. However when the goal was not accomplished, the only other option was to control and observe the children’s situation as closely as possible. We will include a short excerpt here of the synopsis of her story and the turning point it ultimately took. In reality the case lasted approximately five years. In the analysis, by putting the social worker as the subject and the storyteller roles, we managed to make the social work practices visible.

The story started with a contact from the maternity clinic’s midwife. The storyteller, the social worker, wrote into her notes that the situation is alarming and extremely grave from the very first phone call. There were intermittent emergency situations, police calls, home visits and attempts to place the children. The reason for not taking the children into care right away was because of the disagreements of psychiatrists’ identification of the nature and cause of mother’s illness. The crucial turning point was an interchange of doctors at the psychiatric outpatient clinic, which caused a re-interpretation of the diagnosis of the mother. The first doctor said that the mother was just tired and needed rest, but the latter defined her as insane and declared her legally incompetent. This statement created the possibility for action to be taken against parents’ will and it removed the hindrance of placing the children in foster care and the mother in mental hospital.

In the actant analysis, the sender represents the deeper level of meaning which lies on the other side of the superficial level of the story, the cultural set of values, from which the value-object is positioned. The actors who reported the case to the child welfare authorities interpreted the situation as endangering the lives of the children and thus requiring the intervention of the child welfare authorities. The task was assigned to the social worker and it was born out of professional obligation and moral responsibility. The social worker was aimed at completing the task at hand and ensuring that the Child Welfare Department and other legal institutions approved of her actions.

The position of anti-subject is inhabited by the mother, despite the fact that the mother expressed a little resistance to the idea of her children being taken into care. The father’s attitude remained harsh and resistant over the course of the entire story. They took turns resisting the social worker’s attempts at having the children taken into care. The social worker’s anti-subject was, nonetheless, the mother. The mother, however, inhabited a number of actant positions within the story, which is indicative of her ambivalence. She was not entirely sure what she actually wanted. The fact that the mother had numerous actant roles also indicates that the social worker’s impression of the mother was quite multifaceted. Her subjectivity is the most visible in the story and her situation is described as extremely conflict laden. The positioning of the mother as the sole anti-subject paradoxically indicates the most dramatic turn in the story, the mother’s loss of her role as the opposing anti-subject after being declared legally incompetent. This led to the loss of her subjective right to be heard in matters related to her own life, which ultimately led to her children being taken into care.

The "villain” of the story was the husband, who abused his wife, did not take responsibility for his family, was, according to his wife, unfaithful, and refused to accept or acknowledge that his wife was in need of both rest and help with childcare. He also refused to cooperate in any way with the authorities. The father is placed in the category of opponent. He was just a little help to the mother. In fact, he was more of a burden. He did not even carry out the ”basic” task of a breadwinner. As such, his actant position changes over the narrative course of the story from being an active anti-subject to the role of both opponent and, paradoxically, helper. This was because by increasing the mother’s burden of having to care for two small babies he also increased her fatigue and decreased her resources, thus hastening the decision of taking the children into care. The actant analysis of the narrative can be illustrated as follows.

Figure 4: Actant analysis of the process of taking the children into care without parental consent

When examining the uppermost level SENDER – OBJECT – RECEIVER we can find the crucial value dichotomy which is more or less apparent in all child protection work. That is the contradiction between two ethos: protecting the weakest and protecting privacy. These are the supreme values of the Western civilization and they are also confirmed by law. Intruding the family means threatening the sacredness of the family. It means that the social workers are approaching something considered as a taboo. The taboo has a dual meaning of “holy” and “forbidden”, but it means also abhorrent, filthy and dangerous (Freud 2001). The taboo is surrounded by the strong social prohibitions and the transgressions are punished severely. In child protection context considering family as a taboo means that the community is controlling the actions taken towards the family. The community’s attitude to child protection measures is glazed with ambivalence. On the one hand it is eager to send the social workers seeking needy children and on the other hand it easily believes parents’ protecting their family life from the intruders.

4 Conclusion

Here we have described two processes of carrying out social work research. They both belong to the category of semiotic analysis. According to our view, study methods and work methods of social work can be examined in relation to each other and through other. The semiotic analysis makes ways of thinking and ways of action that have been considered self-evident seen. There are a number of similarities in social work practices and in the process of doing research (Fook 2002), as both concern the divisions between interpreted reality and culture. We can use the social worker’s research abilities to help us open the actual process of engaging in social work. In this context, methodology refers to the social worker’s systematic examination of her own actions (see, for example, Karvinen 1993, 168). The concepts of methodology, critical reflection and analytical examination are related in terms of their content. We are used to putting into use of these concepts in the everyday social work practice.

Semiotic interpretation can be applied to research-oriented development programmes in social work. Social workers use semiotic tools to analyse their work individually, in groups or with social work researchers. This allows us to reveal the hidden practices which define social work, for example the values, norms and power structures which define the interactions between social workers and their clients.

In order to be able to use semiotic tools in practice, a social worker has to have studied the theory behind them. The abstract nature of semiotic models allows them to be used in a range of situations. Semiotic tools are context-free tools of modelling social work, which can be attached by the social worker to a specific time, place and situation. Semiotic models allow social workers to distance themselves from various constant and complex aspects of their everyday work. For example, the semiotic square can highlight the social worker’s rights and responsibilities related to his or her clients, which are recurrent. Semiotic interpretation reveals both the identities which are opened for clients during the social work process as well as well as those which can be excluded. The actant model, for its own part, highlights the actors’ positions and power schemes, even as they change.

The study of the practice of social work, which aims at the joint formation of knowledge by those involved (Satka & Karvinen-Niinikoski & Nylund 2005, 12), can be based on the semiotic assignment of meaning. In it, social workers and researchers jointly produce new knowledge, which means that the semiotic modelling of social work redefines the relationship between social work expertise and the social sciences. This creates possibilities for social workers to critically examine the knowledge produced in their work and enables processes in which social power structures are renewed or dismantled (Laine 2005, 185). The development of methodology from a research-based point of departure highlights the characteristics of the knowledge required in order to engage in social work. This facilitates the sovereignty of the field of social work and helps us to avoid a situation in which social work is seen as based, for example, solely on psychology or law, both of which are based on the entirely different concepts of knowledge.

Semiotic interpretations concretise and contextualise values into specific situations, thus allowing them to be concerned with (see, for example, Ife 2001, 138). For example, we can use actant analyses to position an institution or society which highlights productivity and the new public management leadership as the opposition.

It is our view that transcending the boundaries between research and practice is becoming easier when social work is strengthening its own discipline in academic field and offers social workers the possibility to apply the tools of social research in the classification of their own work. It is our hope that in the future we will see research projects in which client-based social work is examined in the arenas inhabited by all those involved in it: service users, social workers and researchers.

References

Adams, Robert and Dominelli, Lena and Payne Malcolm 2005: Engaging With Social Work Futures. In Adams Robert, Dominelli, Lena, Payne Malcolm (eds.) Social Work Futures, pp. 293-299. Crossing Boundaries, Transforming Practice. Palgrave Macmillan: Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire.

Prince, Gerald 1987: A Dictionary of Narratology. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Chandler, Daniel 2002: Semiotics: The basics. New York: Routledge.

Dominelli, Lena 2005: Social Work Research: Contested Knowledge for Practice. In Adams Robert, Dominelli, Lena, Payne Malcolm (eds.) Social Work Futures. Crossing Boundaries, Transforming Practice, pp. 223-236. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan.

Fook, Jan 2002: Social Work. Critical Theory and Practice. London: Sage.

Freud, Sigmund 2001: Totem and taboo: some points of agreement between the mental lives of savages and neurotics. London: Routledge.

Greimas, A. J. 1980: Strukturaalista semantiikkaa. Helsinki: Gaudeamus.

Greimas, A. J. 1987: On meaning. Selected Writings in Semiotic Theory. London: Frances Pinter.

Greimas, A. and Courtes, J. 1982: Semiotics and Language. An Analytical Dictionary. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Humphries, Beth 2005: From Margin to Centre: Shifting the Emphasis of Social Work Research. In Adams Robert, Dominelli, Lena, Payne Malcolm (eds.) Social Work Futures. Crossing Boundaries, Transforming Practice. pp. 279-292. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan.

Ife, Jim 2001: Human Rights and Social Work. Towards Rights-Based Practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Karvinen, Synnöve 1993: Metodisuus sosiaalityön ammatillisuuden perustana. In Riitta Granfelt, Harri Jokiranta, Synnöve Karvinen, Aila-Leena Matthies, Anneli Pohjola (eds.): Monisärmäinen sosiaalityö, pp. 131-173. Helsinki: Sosiaaliturvan keskusliitto.

Laine, Terhi 2005: Turvakotityön käytännöt, asiantuntijuus ja sukupuolen merkitykset. Helsinki: Yliopistopaino.

Lévi-Strauss, Claude 1987: Anthropology and Myth. Lectures 1951-1982. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Mounin, Georges 1985: Semiotic Praxis. Studies in Pertinenece and in the Means of Expression and Communication. New York and London: Plenum Press.

Potter, Jonathan 1996: Representing Reality. Discourse, Rhetoric and Social Construction. London, Thousand Oaks, New Delhi: Sage.

Riessman, Catherine Kohler 1994: Preface: Making Room for Diversity in Social Work Research. In Riessman Catherine Kohler (ed.) Qualitative Studies in Social Work Research. Thousand Oaks, London, New Delhi: Sage.

Saurama, Erja 2002: Vastoin vanhempien tahtoa. Tutkimuksia 7. Helsinki: Helsingin kaupungin tietokeskus.

de Saussure, Ferdinand 2006: Writings in General Linguistics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Satka, Mirja and Karvinen-Niinikoski, Synnöve and Nylund, Marianne 2005: Mitä sosiaalityön käytäntötutkimus on? In Mirja Satka & Synnöve Karvinen-Niinikoski & Marianne Nylund & Susanna Hoikkala (eds.) Sosiaalityön käytäntötutkimus, pp. 9-19. Helsinki: Palmenia-kustannus.

Sebeok, Thomas A. 1986: The Doctrine of Signs. In John Deely, Brooke Williams, Felicia E. Kruse (eds.) Frontiers in Semiotics. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Sulkunen, Pekka 1997: Todellisuuden ymmärrettävyys ja diskurssianalyysin rajat. In Pekka Sulkunen, Jukka Törrönen (eds.) Semioottisen sosiologian näkökulmia. Sosiaalisen todellisuuden rakentuminen ja ymmärrettävyys, pp. 13-53. Tampere: Gaudeamus.

Sulkunen, Pekka and Törrönen, Jukka 1997a: The production of values: The concept of modality in textual discourse analysis. Semiotica 113-1/2, 43-69.

Sulkunen, Pekka & Törrönen, Jukka 1997b: Constructing speakers’ images: The problem of enunciation in discourse analysis. Semiotica 115-1/2, 121-146.

Törrönen, Jukka 2000: The Passionate Text. The Pending Narrative as a Macrostructure of Persuasion. Social Semiotics. Vol 10, No. 1, 81-98.

Author´s Address:

Terhi Laine / Erja Saurama

Diaconia University of Applied Sciences / University of Helsinki

Welfare Services Programme / Department of Social Studies

Sturenkatu 2 / POB 18

Finland / FIN-00014

Tel: ++35 8400 237775

Email: Terhi.Laine@diak.fi / erja.saurama@helsinki.fi

urn:nbn:de:0009-11-24548