The Integration of Formal and Non-formal Education: The Dutch “brede school”

1 Introduction

The Dutch “brede school” (BS) development originates in the 1990s and has spread unevenly since: quicker in the primary than secondary educational sector. In 2007, there were about 1000 primary and 350 secondary BS schools and it is the intention of the government as well as the individual municipalities to extend that number and make the BS the dominant school form of the near future.

In the primary sector, a BS cooperates with crèche and preschool facilities, besides possible other neighborhood partners. The main targets are, first, to enhance educational opportunities, particularly for children with little (western-) cultural capital, and secondly to increase women’s labor market participation by providing extra familial care for babies and small children. All primary schools are now obliged to provide such care.

In the secondary sector, a BS is less neighborhood-orientated than a primary BS because those schools are bigger and more often located in different buildings. As in the primary sector, there are broad and more narrow BS, the first profile cooperating with many non-formal and other partners and facilities and the second with few. On the whole, there is a wide variety of BS schools, with different profiles and objectives, dependent on the needs and wishes of the initiators and the neighborhood. A BS is always the result of initiatives of the respective school and its partners: parents, other neighborhood associations, municipality etc. BS schools are not enforced by the government although the general trend will be that existing school organizations transform into BS.

The integration of formal and non-formal education and learning is more advanced in primary than secondary schools. In secondary education, vocational as well as general, there is a clear dominance of formal education; the non-formal curriculum serves mainly two lines and objectives: first, provide attractive leisure activities and second provide compensatory courses and support for under-achievers who are often students with migrant background.

In both sectors, primary and secondary, it is the formal school organization with its professionals which determines the character of a BS; there is no full integration of formal and non-formal education resulting in one non-disruptive learning trajectory, nor is there the intention to go in that direction. Non-formal pedagogues are partly professionals, like youth- and social workers, partly volunteers, like parents, partly non-educational partners, like school-police, psycho-medical help or commercial leisure providers.

Besides that, the BS is regarded by government educational and social policy as a potential partner and anchor for community development.

It is too early to make reliable statements about the effects of the BS movement in the Netherlands concerning the educational opportunities for disadvantaged children and their families, especially those with migrant background, and combat further segregation. Evaluation studies made so far are moderately positive but also point to problems of overly bureaucratized structures and layers, lack of sufficient financial resources and, again, are uncertain about long-term effects.

2 Present situation of Dutch educational system

The EFA – Education for All by 2015 – agenda calls for a comprehensive approach to learning in which non-formal education is an essential and integrated part. (…) Improved monitoring of the supply and demand for non-formal education is urgently needed at the national and international levels. [1]

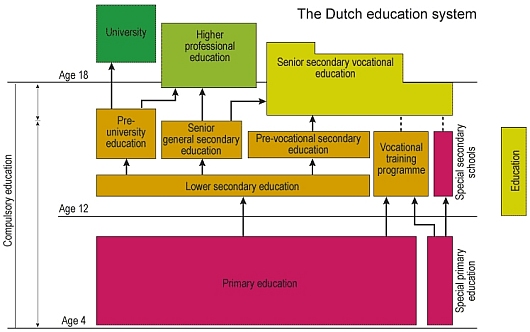

As in many European countries, there is a lively, even fierce public debate going on in the Netherlands about shortcomings of the present educational systems – and where to look for better solutions to old problems. [2] In order to properly contextualize the development and state of the “brede school” (BS), one has to take notice of the main points of critique; they are manifold and touch practically the structure of the whole educational system. We will pay attention to six most neuralgic spots which the BS is supposed to attack (see scheme educational system Appendix 1).

-

Until recently there was a severe shortage of care facilities for pre-school children 0-4 years. While there are now more places available, demand is growing (du Bois-Reymond 2009). Not all (migrant) families with children who need preparation for primary school use pre-school facilities. Also the professionalization of the staff is inadequate and the groups are too large to effectively stimulate the cognitive (language proficiency) and social development of the children, particularly of migrant children.

-

Formally the educational system is transparent and allows for changing levels and tracks, but practically students get stuck in their respective level and track after transiting from primary school (4-12 years) to secondary school which is highly segregative and divides the student population into three big streams: vocational education, and A and O pre-university level. Early selection is of specific disadvantage for junior vocational high school students who have to choose too early for a vocation of their liking and capability with little chance to mend wrong educational choices.

-

Within vocational education there are four streams, the lowest is for the very low achievers, the highest includes more theoretical components. The lower streams produce high rates of early school leavers and absenteeism; up to 30% of the students leave school without the required start qualification (at least three years vocational education with certification plus two years further vocational education) and will therefore face unstable employment or unemployment. [3]

-

The majority of students with migrant backgrounds [4] populate the lower streams of vocational education; they are to an extreme extent underrepresented in senior high school and are overrepresented in the rates of early school leaving, truancy and lack adequate labor market prerequisites.

-

The majority of all students regard school as necessary but experience their curriculum very often as boring and teaching methods as schematic; their learning potentials are by no means fully exploited. At the same time they are overburdened with too many subjects, leading to fragmentized knowledge; there is also an excessive amount of student assessment tests which add to student (and teacher) attitudes of alienation from what education and learning could mean.

-

Dutch teachers suffer from low payment, low social status and low career perspectives. The teacher education (let early childhood education) is in many respects below required standards for a modern knowledge and information society, the needs of contemporary children and young people, and prepares teachers insufficiently for an ever more heterogeneous student population. There is a severe teacher shortage; it will increase in the near future.

These and many more detailed critiques [5] lead to the following demands:

First, the entry into primary school should be preceded and accompanied by a rich kindergarten curriculum for all children, and especially for migrant kids. Working parents (mothers) should be secured of an encompassing caring system for their children.

Second, the abhorrent high rates of early school leavers, especially in vocational training tracks in secondary education, must be combated.

Third, the educational chances of disadvantaged students, particularly among ethnic-minority groups, must be enhanced.

Forth, in order to realize these three demands, existing discontinuities in the total educational trajectory of a child must be converted in one smooth trajectory, leading the student gently and without breaches to the following level; extra financial, organizational and staff resources are necessary to engineer continuous learning lines. Existing facilities such as remedial teachers, youth workers and youth help services, advisory centers for parents etc. operate inefficiently and must coordinate their work fields much better than is now the case.

Fifth, the heavily cognitive-based curriculum and teaching methods must be enriched with non-formal learning approaches which stress social competence and integrate separate subjects into more meaningful knowledge units and projects.

About this last point, there is intense controversy in the public and educational community, framed in the concepts of “new learning” versus the traditional curriculum. “New learning” with its emphasis on the development of competencies and self-administered knowledge acquisition had been regarded as a panacea for almost all evils of formal education in the preceding eight or so years. It is advocated by its propagators as a remedy for unmotivated students and the possibility to break up the stale traditional curriculum. That has provoked the reaction of many defenders of the “old learning”, especially among teachers who work in vocational education. Their (migrant) students are not served by letting them find out what they want to learn and asking them to give meaning and structure to their own learning process, teachers and other opponents argue convincingly. But also in senior high school there is much resistance, not only of teachers but also of students who feel they are simply let alone with what and how they have to learn. In teacher training colleges, the “new learning” ideology has the effect that teacher students miss a coherent curriculum and decent instruction; instead they are held busy with self- and group reflection on their learning accomplishments and have to pick their way through endless quasi self-evaluating procedures.

Obviously, sensible educationalists would plea for a sensible combination of both approaches, old and new, but that is not easy to realize in the existing educational system with a teacher staff who is not trained in flexible work forms and is frustrated by an avalanche of contradictory reforms designed by subsequent educational ministries without waiting for proper analyses of the effects of foregoing reforms, and without taking notice of counter-effects. [6]

This is, in broad brushes, the educational landscape into which the “brede school” is introduced, and we will show what its potentials and restrictions are to make the Dutch educational system better work.

3 Development of the “brede school” (BS); definitions, concepts, objectives

The development of the BS dates back to the mid-1990s and commenced in the primary school. In the beginning it had two main tenets:

-

Combating educational deprivation by offering extra-curricular activities for educationally disadvantaged children;

-

Providing care facilities after school for children of working parents/mothers.

Since then, the BS-movement has spread all over the country and counts now in the hundreds, primary as well as secondary schools. In 2007, there were about 1000 primary and 350 secondary BS schools [7] and the aim of individual municipalities and the government is to create a comprehensive supply in the coming years.

In principle, the concept of the BS encompasses all children 0-18 years. Most BS schools in the primary sector cooperate with pre-school care facilities and crèches, thus offering care and education from 0-12 years. In secondary education, the BS is primarily developed for 12-14 year olds and less so for older students who do not want to be involved in extra-curricular activities any more.

The terms BS has many meanings and is realized in many different forms, but basic commonalities are:

-

The cooperation between an existing school and one or more existing institutions, like a crèche, a sport club or any other child, youth or parent-related service;

-

The activation of potential and real partners (to be) involved in a BS, like a library or a neighbourhood association.

The most general fitting definition of a BS is that it is a network organization with the individual school as the spin in the web. We will see later (Chapter 5) that there are small and extended networks, but in any case it is the school which is at the center.

There is broad consensus in Dutch society that the initiation of BS must come from the school and/or local actors; must not be imposed from above. That complies with the long standing Dutch tradition of private schools besides state schools. [8] While in the begin years, the government looked benevolently from a distance at the development of the BS, the last years one observes more active steering through financial incentives, explicit inclusion in government documents, and issuing evaluation reports. The BS movement is thus becoming part of a much broader social policy and evolves in community development. An example is the resolve of the government to engage BS schools in its campaign of transforming 40 neighborhoods with most severe problems into 40 “success neighborhoods”. [9]

More government involvement does not mean though that the form and the partners of a BS are prescribed. Here the individual school – or rather the school board - has full freedom to decide about scope and emphasis of the program, as we will see in the following chapters.

The objectives of the BS differ between primary and secondary education; we will concentrate here on the latter. [10]

As regards the students, objectives are:

-

Development of social competence (social, sportive, creative talents; positive self-image, self-respect, self-reliance; tolerance and respect for the other);

-

Strengthening the binding with the school (students should feel at home in school; reducing of truancy and early school leaving; keeping students longer in school or bringing them back into it);

-

Furthering social participation (useful leisure activities; keeping students off the street; helping them to find their way in society);

-

Enhancing school accomplishment (learning to learn; development of language proficiency).

Analyzing these student-bound objectives [11] , which are compounded of what secondary schools themselves named, we find strong emphasis on the wish and hope of teachers and society at large to integrate students at risk (back) into education and (later) into work by making them self-sufficient and competent members of society (and the labor market). It is obvious from these objectives who those students are: underachievers and minority students who need compensatory aid. Nevertheless there are more general educational goals which apply to all students, like the acquisition of broad social competencies, learning to find and use relevant information, and making optimal use of educational opportunities.

Objectives concerning the organization:

-

Creating a positive and secure school climate;

-

Enhancing the reputation of the school.

These objectives point to a growing concern in the public and educational community about violence in and around schools; a tendency which has grown over the last years and has led to various programs designed to guarantee a secure school environment. It concerns predominantly junior vocational high schools in neighborhoods with high rates of minority populations. Converting existing schools into BS means, first of all, increasing budgets for extra activities and extra personnel. Such additional resources are used to intensify efforts to keep students in the educational boat.

Enhancing the reputation of the school points to increasing competition between schools (school boards). Schools are financed according to the number of enrolled students; criminal incidents at school may lead to lower enrolment and subsequently to cuts in subsidies and staff. Schools must also be afraid of ranking low on the nation-wide published ranking lists.

Objectives connected to the parents of students:

-

Tightening the relation between school and parents;

-

Conveying information about the development (and problems) of their child to the parents and addressing their educational responsibility);

-

Supporting parents with the education of their child (advising them about low-threshold services).

Parent participation is a vulnerable spot, particularly in junior vocational education. Teachers do not have time to regularly see the parents of their students and the parents, certainly migrant parents, do not find their way to school easily. Although teachers realize the importance of parent participation, they do not have the means (time, energy) to make active work of it. They would, within the framework of the BS (but also outside it) rather rely on social workers and other non-teaching personnel to communicate with (migrant) parents.

Objectives touching the relation between the Bs and the neighborhood:

-

Improving the security in the neighborhood (see to it that youths do not hang around in the street; participate in crime prevention; help improving the relationship between youths and other inhabitants in the neighborhood);

-

The BS as the center point of the neighborhood (make the BS the central location and facility in the neighborhood, thereby enhancing neighborhood cohesion).

This last objective is the broadest and most essential of all objectives of the BS. It points to the intention of the government to make the BS the center of community development and lies at the heart of the new social policy of the welfare state, fostering social integration through active social participation, to begin with where each citizen lives, in their respective neighborhood.

What is now the relationship between the formal school curriculum and the non-formal education offers?

First of all one must realize that in the Dutch definition and practice of the BS, “non-formal” is not restricted to educational activities. As emanates from what already has been stated – strong focus on students-at-risk and how to integrate them – the non-formal part of the BS concerns social and youth care, crime prevention and other professional help at least as strongly as non-formal education in a more restricted meaning. The extension with these functions – as a matter of fact the integration of youth care in the school – implies to establish a whole team of non-educational professionals (“zorgteam”) who take care of the social and emotional development of the students, keep in contact with the parents and connecting them with other professionals who are specialized in psycho-social and educational and upbringing problems, offer language courses for migrant parents etc., thereby relieving the strain on the teachers.

There is a clear dominance of the formal curriculum and a sub-dominant role of non-formal education in the ideology and practice of the BS. It derives from the centrality of the school in the network which has to be knit to make a BS. Non-formal education is defined as adding to formal education, not altering it through a far-going integration of both.

Non-formal education elements may be either included in the day-program of the formal curriculum (additional literacy education) or, more often, offered after and outside the formal curriculum, like summer schools, Saturday schools, excursions, sport events or feasts, or courses and projects on a regular basis conducted by teachers who are given extra les hours and/or pay, or by hiring additional personnel for the afternoon program. Most non-formal offers are leisure activities, sport, music and culture in particular, and are therefore voluntary. In some cases the activities are obligatory to help pupils fill up knowledge gaps.

Non-formal education personnel may be hired by the school(-board) from the municipality (like youth workers) but also on the free market, like artists, sport trainers, theater companies to give a performance, or any other service and activity the school regards attractive for their students. Schools have budgets to finance additional staff and activities which come from the municipality, the government and possibly other income sources, like subletting school rooms to commercial clubs or acquiring sponsor donations. Parents are charged with (small) contributions.

Looking at the development of the BS so far, one can summarize it as follows:

-

The BS has developed from a facility primarily for primary schools to a new school form which is meant for all schools. Nevertheless, there are still many more primary than secondary BS schools. Secondary schools are big and complex organizations which it is less easy to instill changes than in the smaller-scale primary schools.

-

Although meant for all students and school types, the development of the BS in secondary education is most vigorous in comprehensive school organizations which combine junior vocational and senior high school education; gymnasiums are separate school forms and have their own extra curricular programs.

-

Students older than 14 years do not want to participate in BS-organized afternoon activities; they feel that they want to spend their spare time on their own terms. This is also the case for (younger) students in exam periods; they stop BS-activities during these periods.

-

Non-formal activities are usually not integrated in the official school curriculum but are offered on a voluntary basis. In that sense it is not the prime goal of the BS to renew the formal curriculum.

-

The objective of creating non-disruptive educational trajectories, ideally from 0 to 18 years, must be taken with reservation: the transition from primary to secondary school with the implied selection and student streaming has not become smoother through BS.

-

The urge of the government to make the BS the hart of community development is ambitious and asks for a far reaching integration of existing facilities and services on neighborhood, municipality and even county level.

4 Social actors and institutions

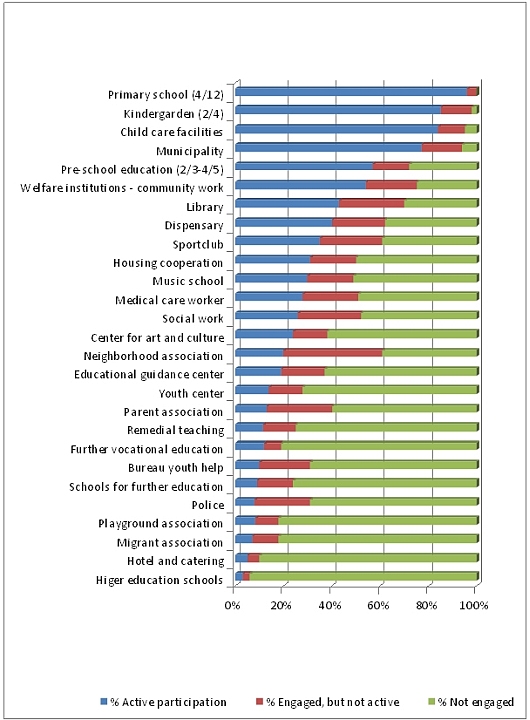

In order to get an idea about the concept of the BS as community development, it is useful to list all social partners and institutions which may be involved in a given BS. Research bureau Oberon (2007) presents such a list for primary as well as secondary BS schools. The lists not only enumerate the participants, they also show the magnitude of engagement in the BS (strong, weak, no engagement).

We comment first briefly on the primary BS list and afterwards more extensively on the secondary BS list.

Primary BS school participants

The scheme [12] (Appendix 2) shows:

-

Practically all primary BS schools work together with kindergarten and child care facilities;

-

The majority of primary BS schools work actively together with the respective municipality and welfare institutions;

-

Cooperation with the local library, sport club and/or music and art schools/clubs is dependent on the availability of such services in the neighborhood; somewhat less than half of the primary BS schools make use of them;

-

About one in three primary BS schools cooperates with municipal health care and social work;

-

About one in three primary BS schools is actively engaged in a neighborhood association; somewhat less than 30 per cent cooperates with a parent organization or a youth club;

-

Other organizations – educational guidance center, bureau youth help, police, housing cooperation, further vocational education, migrant associations – are less prominent partners.

Comment

We concentrate on the two main tenets of the Dutch government which is, first, to combat educational disadvantages by creating one non-disruptive educational trajectory and, second, to make the BS the hart of community development.

One of the biggest accomplishments of the BS movement is the meanwhile well-established cooperation of primary schools with kindergarten and childcare facilities (Schreuder et al. 2005). This cooperation can take on various forms, from physical integration in one building with regular interaction between kindergarten, crèche and primary school personnel and involved parents, to looser cooperation with the pre-school institutions operating (more) independently from each other, and being located in separate buildings; the latter form of cooperation is still more dominant because of housing problems which hinder one-roof constructions.

Parental participation in primary BS schools is certainly higher than shows in the below-30 per cent of parental associations; participation and exchange about the children will take place in an informal manner between parents and caring/teaching personnel. But exerting parental influence on the BS would demand more organized structures; parents do not seem to feel the need for it – nor do most BS schools for that matter. Also the degree of organization of migrant parents is low: 5%. This is partly because not all primary BS schools are located in neighborhoods with (high percentages of) minority groups. But low figures also point to a certain distance between school and minority parents (Distelbrink & Hooghiemstra 2005; Pels & de Haan 2007).

As concerns the goal of a non-disruptive educational trajectory, it is conspicuous that there seems to be hardly any cooperation between primary and secondary schools; less than 5 per cent of primary BS schools report such cooperation. Here we come across a main obstacle of a BS for all children from pre-school age to school leaving age. The deep breach between primary and secondary school is not bridged by the “brede school” and is, as far as we can see, neither an explicit tenet of the individual school – exceptions exist – nor the government or the municipalities so far.

What does that mean for combating educational disadvantage? The broadly established cooperation between pre-school/care and primary school is a big step in the right direction. Yet it does not necessarily mean active and professional furthering of disadvantaged children from two/four to twelve years. It may – and often will – mean no more (but certainly no less) than creating a homely climate in the pre- and primary school and later some remedial help for (migrant) children in the acquisition of basic skills (reading; numbering). [13]

The cooperation of primary BS schools with various municipal and other community facilities, public as well as private and commercial, is in line with the tenet of community development; in many neighborhoods the school is indeed “the beating hart” of the community and many primary schools are busy with enlarging their networks and are strongly encouraged by the government and municipalities to do so.

Secondary BS school participants

The scheme [14] (Appendix 3) about cooperation in secondary BS schools shows a different picture from the primary BS schools:

-

Cooperation with the municipality and its services, including the police, ranks highest;

-

Sport clubs and art centers rank high but do not reach half of the BS schools;

-

Parent associations are present in about one in three BS schools;

-

Neighborhood associations are present in only 15% of the BS schools;

-

Youth clubs/centers are present in about one quarter of the BS schools;

-

More than one in three BS schools cooperates with local firms and companies;

-

More than one in five BS schools works actively together with a primary school, higher professional and academic education, and over 30 percent cooperates with schools of further vocational education.

Comment

The close cooperation with the municipality takes the first place on the list but is still less frequent in the secondary BS than in the primary BS (50 vs. 70 per cent). That points to the fact that secondary schools form organizational clusters which may include twenty or more schools, scattered through the city or even spread among different communities and which are administered by one school board. The ties with the neighborhood and municipality are therefore less close than in primary BS schools in local surroundings. It is the school board which negotiates with the municipality, not the individual school. [15]

The relative distance of secondary BS schools from the neighborhood also explains, at least partly, the low participation rate of parent associations.

That leisure clubs etc. are partners in less than half of the schools, has to do with the age of the students and the formal curriculum: above the age of 12 years, students have their own leisure agendas and do not want to be obliged by the school. In addition, homework and preparation for tests and exams eat up their time.

The fact that the police as cooperation partner ranks high on the list (fifth position; over 40 per cent), points to big problems secondary (lower vocational) schools face concerning (small) criminal offenses, mainly drugs and violence between students, incidentally between students and teachers. [16] Police is not only called in incidentally; many schools have built up regular contacts with police officials to monitor schools/school plains and give information lessen to the students.

Concerning the tenets of integration, non-disruptive educational trajectories and enhancing school performance of low (migrant) achievers, our (temporal) conclusion is not unequivocal. On one hand, there is cooperation with previous and subsequent schools (see last dot); there is also cooperation with local firms and enterprises. That seems promising, although 20% cooperation means 80% less or no cooperation. On the other hand it is not clear how substantial and permanent such cooperation is and how it increases the educational chances of low achievers. For example, the cooperation between senior high school and university consists in inviting the best and most motivated students of the last years of general secondary schools to follow special university programs to motivate them to enter a university education. Such programs may (and will) attract well-achieving students who probably would go to university anyhow; programs may also be particularly designed for students with minority backgrounds in order to increase their numbers in higher education. Such initiatives are rare though.

More important, it seems, is to increase active cooperation between primary and secondary schools. That cooperation would have to come from both sides, primary as well as secondary school; such cooperation scores (very) low on both lists.

Cooperation with local enterprises may be part of the traditional curriculum in vocational education but may also be innovative for non-formal curricula (see examples of BS below).

Community development and the role of secondary schools in it, is a highly complex process which does not only involve individual schools and neighborhoods but demands the coordination of practically all social sectors of a town or city. Especially the housing sector must be involved in order to rebalance segregated neighborhoods and further more integration between Dutch and migrant groups in and outside education. While there is growing consciousness in the public and among politicians about this problem, it becomes also clear that urban segregation processes are very hard to revert.

5 Types and profiles of BS schools

We said in the beginning that there are many different forms of brede schools in the Netherlands; the BS-movement has developed on the basis of individual schools, neighborhoods and communities. As a matter of fact, the diversity of the BS development makes it dubious to speak of THE brede school; there is none, we will have to differentiate by presenting different types and profiles.

Broad vs. narrow

A first distinction to be made is that between broad and narrow BS profiles. That distinction came already to the forefront in the lists of preferred and realized cooperation between the school and other services and institutions. Not all schools cooperate with all possible partners. There are primary BS schools which go very far in their cooperation, including practically all available and useful resources in the neighborhood and municipality. Ideally those schools have one big (new) building at their disposal to house crèche, playrooms, classes, teacher rooms, sport and recreation halls, one or more cantina’s, PC locales and an aula for various events to assemble. In the evening or weekends and in after school time the building would be open for youngsters and youth workers, for parent and other neighborhood groups, and for parties and feasts.

This far-reaching integrated school type is in all respects the exception with housing in separate buildings the main obstacle although there are (primary) schools which realize multi-integration even if the different parts are housed in different locations. Most primary BS schools belong to the narrow type, cooperating mainly or exclusively with associated crèche and kindergarten (but see further “the childcare school”).

In secondary education the situation is more complex. First of all one has to distinguish between junior vocational and senior high schools. Most secondary schools are combinations of both, general and vocational, but they remain separated in their program and levels. [17] That makes for different BS features and emphasis of extra-curricula activities. Within one school there will therefore be different approaches to non-formal education. Certain extra curricula in the leisure sphere will be integrated, others will be offered to specific student populations. Usually afternoon activities are restricted to the lower age groups (12-14 years).

As in primary schools, non-formal education in secondary BS schools may be broad, including many different social actors and institutions, not necessarily within physical proximity of the school, or be restricted to fewer offers; sport and other leisure activities take the main bulk of all non-formal activities. They are bought by the school which reserves a certain amount of its budget for financing also commercial programs and courses. Dependent on the program, the parents would have to contribute to meeting the costs. The same holds for primary BS schools.

Examples of broad and integrated non-formal programs for all students, vocational and general, do exist but are the exception.

Formal and non-formal curricula separate or integrated

As a rule, the BS in the Netherlands, primary as well as secondary, is not meant per se to integrate formal and non-formal education. The position of the “formal school” is in no respect questioned. Rather, non-formal elements are introduced in the after school time; there are exceptions. In primary schools there is more curricular integration than in secondary schools.

“Non-formal” does not so much refer to education but rather to additional resources given to the school to do its job better than it could without such resources. To keep youngsters busy in the school-free hours and prevent them from hanging around in the streets and being a nuances to other neighborhood dwellers by offering them attractive leisure offers is an element of non-formal education in that sense. Youth workers and youth care institutions are viable partners to relieve the school from problem students.

To clarify this point further, one has to go back to the notion of community development. Community development is not the same as developing existing schools into comprehensive schools. It is meant in first instance to strengthen neighborhood cohesion. Citizens must learn what it means to be an active member of society, they must learn to take their rights and responsibilities, learn to live with compromises between different ethnic-cultural groups, and reestablish trust and respect for each other. All that implies education and competence learning, and the school should be a major player in the game, but it does not necessarily challenge the existing separation between formal and non-formal curricula.

Three types of BS

On the basis of an inventory of BS schools in the Netherlands, research bureau Oberon ( 2007, p. 84 f) discerns three main types or profiles [18] :

-

The childcare school;

-

The disadvantaged school;

-

The neighborhood school.

The childcare school

The childcare school is becoming obligatory since the government has issued a regulation that every primary school must offer day and after school care for the children and pupils whose parents want and need such care. As the list of cooperation showed, the combination of pre- and primary school facilities are common. Not all schools have succeeded yet to meet the prescribed goal of establishing a fully integrated organization of childcare, pre- and primary school with facilities for children to stay at school between morning and noon lessen and a stimulating program of non-formal activities in the afternoon. Flexible opening and closure hours are highly recommended and wished by the parents. Location of childcare and school in one building is much preferred but not (yet) the rule.

The childcare school is clearly the result of growing labor market participation of women for whom the existing primary school with an interrupted school day was detrimental for mothers to take on a job. The Dutch family model is based on the “one and a half model” with the male/husband working full-time and the female/mother working part-time. That model is still dominant, but women are strongly encouraged to work more hours (du Bois-Reymond & Distelbrink 2008).

The disadvantaged school

BS schools with profiles for disadvantaged pupils are not new; the 1970s with social-democratic educational policies initiated and financed compensatory enrichment programs for disadvantaged (working-class) pupils. Since then there were countless programs and educational initiatives to upgrade the school achievement of disadvantaged pupils which now trade under the name and the roof of a “brede school”.

BS schools for disadvantaged pupils target children and their families who need extra help in and outside school. These schools, primary as well as secondary/vocational, are by definition located in problem neighborhoods, usually ethnic minority-dominated. Compensatory programs are administered to children to enhance their language proficiency, instill in them pleasure to read, teach them adequate social behavior, and channel them through to other professionals, like health services, remedial teachers or sport coaches. The non-formal and enrichment curricula are partly voluntary, partly obligatory and they are partly integrated in the formal program.

Parent participation is particularly encouraged and special programs are offered to them if they (or the social worker) feel they have problems with the education of their children.

On the whole, the permeability of the educational system has not become better for disadvantaged (ethnic-minority) students through the introduction of the BS; in individual cases it has. Those exceptional schools have broad profiles with more rather than less integrated curricula. Ideal for these (as for all) children would be a non-disruptive trajectory from pre-primary to secondary school with full integration of formal and non-formal education.

The neighborhood school

The profile of a neighborhood school overlaps with the two foregoing profiles. It could be schools in primary (see van Oenen & Valkenstijn 2003) or secondary education, and it could concern schools with a regular or a disadvantaged student population. Emphasis is laid on furthering the social cohesion of the neighborhood by creating and using facilities which bring people together, making them feel at home and responsible for their street, their quarter, their co-dwellers, the school for their children. Voluntary work of the parents and other neighbourhood and city dwellers is strongly stimulated.

Neighborhood schools are not only a means of creating social cohesion in big cities; they are of special importance in rural areas which are endangered by depopulation. It is not the integration of formal and non-formal education which is central in the concept but rather the need of concentrating existing facilities – from GP to post office and bank, from special shops to youth work and health services. Small schools which would otherwise have to be closed can be preserved that way.

6 Professionalization of teachers and social workers

The infra-structure of a brede school is complex: besides the regular teacher staff there is a multitude of official and voluntary persons in and around the BS school to cooperate and interact. Although there is usually not much integration of the formal and the non-formal curriculum, certainly not in secondary education, there is still need to communicate. It seems that there is no sharp cleavage between teachers as opposed to youth workers which would negatively influence the communication between these two groups of professionals. The public discussion we briefly sketched in Chapter 2, is rather fixated on the deplorable position of the teachers, not so much or at all, the social and youth workers. That might be the reasons why in research and evaluation reports about the BS the question of professionalization and possibly problems do not figure highly while there is growing concern about the quality of teacher training in general. [19]

Perhaps one might say it is because of the separation between formal and non-formal education that the relationship between teachers and “non-teachers” is generally not regarded as problematic: if the two educational spheres are autonomous, each professional has his or her own field of operation which is respected by the other party.

We must make a difference between primary and secondary BS though. As we have pointed out earlier, in primary BS, there is more integration between formal and non-formal education, and between the various fields the professionals work in. It depends highly on the head of the school and the teaching staff if the total BS-team works together in harmony or if there are tensions, for instance between the responsible persons in charge of the pre-school and those of the primary school.

There is growing concern about the quality of the crèche and preschool professionals. Upgrading their initial education (on middle vocational level) takes place through postgraduate courses. Also there are initiatives of the government to establish obligatory quality standards for personnel and location of daycare for pupils.

As concerns secondary BS schools, their formal and non-formal teams might be more or less integrated – and both options may work. Even if the teams operate rather autonomously from each other – here the teaching staff, there the social and youth workers and others – that can still resolve in a well-supportive and lively school where students find much stimulant for afternoon activities and help for possible problems. In as much as there is more integration, evidence points to close cooperation between formal and non-formal pedagogues and professionals to create viable support structures for disadvantaged students – mostly of migrant groups and in vocational education.

Said that, one must not deny that there are tensions between formal and non-formal professionals resulting from different professional cultures, priorities and administrative conflicts. The report Brede Scholen in Nederland (2007, p. 37; 59) alludes to some tension when it states that besides financial shortage, one of the biggest problems of BS schools are shortcomings in cooperation:

-

Partners are afraid to loose their own (professional) identity and would rather (like to) stay on their own;

-

Not all partners are equally convinced about the advantages of a BS;

-

The establishing and running of a BS involves additional work and engagement;

-

The (primary) BS does not succeed in developing a commonly accepted educational vision.

These problems are not signaled by all BS schools and do not necessarily accumulate in one particular school. There is, to our knowledge, no information about the extent and magnitude of such problems, and to what kind of factors they would be related to.

The list of signaled problems also includes the statement: “The brede school is too narrow” (p. 59) (see also Chapter 5 and Appendixes 2 and 3). It remains to be seen if there will develop a trend to “broaden the brede school”.

There is also the problem of incongruous regulations for the different partners within a BS, deriving from different political levels (municipality; province, government), associations (parents, ethnic minorities) and teacher training institutions. And there is the problem (see Chapter 2) of too many initiatives and experiments in too short a time to give the teachers and others enough room and relaxation to develop the BS on their own terms and tempo.

A last point we want to stress: it is conspicuous that in the BS literature and research hardly any attention is paid to reforming and restructuring the teacher training, early childhood and preschool and social-pedagogical training in order to create well-qualified personnel for the BS of the future.

7 Conclusions

The first conclusion we can draw is that the brede school in primary and secondary education will become the dominant school form in the near future. Gymnasiums will not be included in the model, they will stay separate but they, too, are obliged to offer day care for their pupils on demand of the parents.

That the BS will become the dominant school form of the future does not mean – and will not mean as far as we can see – that existing schools (school boards) will be obliged to enter a BS construction; the gymnasiums are a point in case. But in as much as there come more and more BS in primary and secondary education, the remaining or hesitant schools will have to follow the trend sooner or later, simply because their competition position is endangered.

Second conclusion: A further spreading of BS schools will not automatically, and probably even not in the long run, lead to the comprehensive school with a non-disruptive trajectory for all children, pupils and students from 2/3-16/18 years. While the breach between pre-school and primary school has been smoothed or, in the best cases, practically worked away, the transition from primary to secondary school at the age of 12 is still a big censure in the life of a child (and their families). Nothing points to developments to ease that transition and the cooperation between a primary and a secondary BS is still marginal.

Third conclusion: There is little evidence that the BS will integrate formal and non-formal education better than it does at the moment (du Bois-Reymond 2010). Formal education is regarded by all partners – and educational politics – as the clear dominant part in the whole of learning and education. In most BS schools, non-formal activities are in the sphere of leisure and, for the disadvantaged, in compensating for lacking social and/or cognitive competences. For those students, the main function of non-formal personnel is to relieve the teachers.

The teacher training is not reformed in order to prepare teacher students for their task of working in BS; they (will have to) learn that in practice. Social and youth workers are by definition better prepared for their work in the non-formal sphere.

Forth: Existing BS schools suffer from coordination problems and bureaucratization which endangers innovative spirit and motivation of the staff. Paradoxically, that danger is smaller for narrow and bigger for broader BS schools.

Integration and cooperation is easier if the various branches of a school are assembled under one roof, particularly for broad BS. That demands expensive housing facilities – which are usually not there.

Fifth: BS schools can help little to combat the growing danger of further segregation between the Dutch and non-Dutch (born) population. One reason is that the different levels in secondary education – vocational vs. general – discriminate against students with migration background; they do not succeed to enter secondary general/pre-university levels in substantial numbers.

Another reason is that many city quarters are segregated and therefore so are the schools; the number of “black” and “white” schools grows. That does not take away that BS schools can operate successfully in many ways in a given neighborhood

Sixth: BS schools are supposed to fulfill the function of community development. In as much as they get and take this function, they need substantial additional financial and organizational resources, as is already planned by the government for 40 selected problem neighborhoods. On the whole though, BS schools complain about too restricted financial means to fulfill their tasks.

Finally: It is too early to make reliable statements about the effects of BS schools as opposed to non-BS schools concerning the academic, social or other achievements of the students. Existing BS schools are evaluated, but it is hardly impossible to control all variables involved and find adequate indicators for comparison. Many practitioners, teachers in particular, have the opinion, based on experience, that schools must become smaller organizations in order to create viable communication structures between teachers and students as well as between all other partners involved.

Appendix 1: Dutch Educational System

Appendix 2: Scheme cooperation primary BS schools

Appendix 3 Scheme cooperation secondary BS schools

[1] EFA Global Monitoring Report 2008, p. 61.

[2] After finishing this expertise, a parliamentary report about the state of the educational system and failing reforms of the last twenty years in secondary education was published (Commissie Dijsselbloem, 13 februari 2008: Onderzoek Onderwijsvernieuwingen

[3] Within one year, youth unemployment rose from 9,3% to 11,4%; young people without start qualification are even harder hit: 15,2% (CBS Webmagazine 26 August 2009).

[4] The four biggest groups of families with migrant background are Turks, Moroccans, Antilleans and Surinam people.

[5] See for instance J. Dronkers 2007.

[6] A parliamentary commission had been installed to evaluate the effects of these contradictory and hastily implemented “reforms” (Enquête Commissie Dijsselbloem 2008).

[7] In fact there are more schools involved than the given numbers suggest because many school organizations consist of several schools which are administered by a school board.

[8] In 1920, a law was issued which guarantees the right to found private schools. They are fully subsidized by the state and have in principal full freedom to make their own program as long as global quality standards are obeyed. In practice the autonomy of the individual school is restricted by the educational policies of school boards, by the many fusions which have taken place in the last 20 years leading to school organizations with up to 3,000 students, and by uniformization through nation-wide test and public school ranking.

[9] See letter Sharon A.M. Dijksma, State secretary Ministry of Education with Jaarbericht 2007: Brede Scholen in Nederland to the chairman/woman of the Tweede Kamer der Staten Generaal (parliament).

[10] See Oberon 2007, p. 14ff.

[11] Symptomatically, students were not interrogated.

[12] Oberon 2007, p. 50.

[13] According to the report of the Advisory Board for Education of 2006, one quarter of the students in the first two forms of secondary vocational education are not able to read their own schoolbooks and one quarter of the pupils in the last form of primary school is two school years retarded in reading capability (NRC Handelsblad 23-1-2008).

[14] Oberon 2007, p. 71.

[15] Recently the growing influence or even pressure of schoolboards on school affairs is critiqued in the national press and among educationalists. See also Studulski 2002 on this problem.

[16] On January 13, 2004, 17 year old Murat shot the vice principal of a secondary school in Den Haag in the head who died as a consequence. Since then special security measures are taken in schools which stand in problem quarters.

[17] The integrated comprehensive school was introduced in the 1970s under social democratic governments but was never accepted as obligatory school form. From the 1980s onwards, individual schools were fused into bigger agglomerations. In the 1990s, a reform was issued which must integrate the first three years (12-15 years) of all school types in secondary education (except gymnasiums). That reform failed. Presently most secondary schools, although under one (or more) roof and administration, are separated in vocational and general tracks and levels.

[18] The interpretation of the three profiles are the responsibility of the author (MdBR).

[19] Primary teachers (4-12 years) and secondary teachers (12-15 years) are trained in higher professional education institutes; secondary teachers (15 + years) are trained in special teacher training colleges, with part of the training given at university level. Gymnasium teachers are trained at the university in their respective subjects with special courses in pedagogy and didactic given in special institutes.

References

du Bois-Reymond, M. 2009: Young parenthood in the Netherlands. Young. Nordic Journal of Youth Research Vol.17, nr. 3 (265-283).

du Bois-Reymond, M. 2010: Chancen und Widerständiges in der Ganztagsbildung. Fallstudie Niederlande. In H.-H. Krüger et al. (Hrsg.) Bildungsungleichheit revisited (Chances and resistent forces in establishing comprehensive schools; case study Netherlands) (pp. 203-220).

Clarijs, R. 2006: Aanzet voor ander jeugdbeleid met wezenlijke rol non-formal education (Another approach in youth service, including a substantial role of non-formal education). Nederlands Tijdschrift voor Jeugdzorg, nr. 5, pp. 201-215).

Commissie Dijsselbloem 2008: Parlementair Onderzoek Onderwijsvernieuwingen. ’s Gravenhage:Sdu Uitgevers.

Distelbrink, M. & Hooghiemstra, E. 2005: Allochtone gezinnen. Feiten en cijfers (Ethnic minority families; facts and figures). Nederlandse Gezinsraad Den Haag.

Dronkers, J. 2007: Ruggegraat van ongelijkheid. Beperkingen en mogelijkheden om ongelijke onderwijskansen te veranderen (The backbone of inequality. Restrictions and possibilities to change unequal educational opportunities). Mets & Schilt: Amsterdam.

EFA Global Monitoring Report 2008: Education for All by 2015. Will we make it? UNESCO Publishing. Oxford University Press.

Handboek Brede School 0-12 Jaar 2007: Utrecht: Oberon/Sardes ( www.oberon.eu ).

Oberon 2003: De Brede School in het voortgezet onderwijs (The brede school in secondary eduction) ( www.oberon-0-a.nl )

Oberon 2005: Brede Scholen in Nederland. Jaarbericht 2005 ( www.oberon-0-a.nl )

Oberon 2007: Brede Scholen in Nederland. Jaarbericht 2007 (www.oberon.eu).

Oenen, S. van & Hajer, F. 2004: De school en het echte leven (The school and real life). Amsterdam: SWP.

Oenen, S. van & Valkenstijn, M. 2003: Welzijn in de brede school. Partners voor levensecht leren (Well-being in the brede school. Partners for learning in real life situations). Utrecht: NIZW.

Onderwijsraad 2007: De Verbindende Schoolcultuur (Binding school culture). Den Haag.

Projectplan Vensterscholen 2003-2004: Gemeente Groningen: Dienst Onderwijs Cultuur Sport Welzijn, Juli 2003.

Pels, T. & Haan, M. de 2007: Socialization practices of Moroccan families after migration: A reconstruction in an ‘acculturative arena’. Young. Nordic Journal of Youth Research, 15, 1, 71-91.

Schreuder, I., Valkenstijn, M. & Hajer, F. 2005: Dagarrangementen in de brede school. Een samenhangend aanbod van onderwijs, opvang en vrije tijd (Child care arrangements in the brede school). Amsterdam, SWP.

Studulski, F. 2002: De brede school. Perspectief op een educatieve reorganisatie (The brede school. Perspectives of an educational reorganisation). Amsterdam: SWP.

Additional BS 1literature

Grinten, M. van der & Studulski, F. 2007: Zicht op de brede school 2006-2007 (A look on the brede school). Amsterdam: SWP.

Haan, J. de 2004: De brede school stap voor stap (The brede school step for step). Voorburg: Besturenraad.

Studulski, F. & Grinten, M. van der 2006: Brede scholen in uitvoering – nieuwe trends en voorbeelden uit de dagelijkse praktijk (Brede scholen in operation – new trends and examples from the daily practice). Amsterdam: SWP.

Verhees, F., Fransen, B., Giebels, E. & Vereijken, P. 2003: Brede school, brede aanpak (Brede school – broad approach). Maarssen: Elsevier.

Author´s Address:

Prof Dr Manuela du Bois-Reymond

University of Leiden

Faculty of Social Sciences

Dep. of Education

Wassenaarse Weg 52

NL-2300 RB Leiden

Tel.: +31(0)71527 4089

Email: dubois@fsw.leidenuniv.nl

urn:nbn:de:0009-11-24522