Youth as Social Service Consumers: the Case of Russia

Alevtina V. Starshinova, Ural Federal University, Russia

Olga I. Borodkina, Saint Petersburg University, Russia

Elena B. Arkhipova, Ural Federal University, Russia

1 Introduction

Despite the cardinal transformations of Russian society in the 1990s, accompanied by the reconstruction of private property in the main spheres of public life, the changes did not affect the social sphere. The state and the subordinate state institutions retained a monopoly position in the social security system. To a large extent, this kind of conservation of the social welfare system was explained by the stable paternalistic expectations and traditions in the relationship between Russian citizens and the state that developed during the Soviet period. At the same time, already in the 1990s, public organizations that were formed under the Soviet regime and the newly emerging NGOs declare themselves as conductors of new approaches in social policy in relation to certain social groups (Kulmala, Tarasenko 2016), in particular social protection of children deprived of parental care (Bindman, Kulmala, Bogdanava 2019; Kulmala, Rasell, Chernova 2017). Later, the approaches proposed by NPOs against the background of growing dissatisfaction of citizens with the social security system significantly shattered the dominance of the state system of public welfare and forced not only to focus the attention of the authorities on the role of NPOs in the production of public goods, but also to take decisive measures to enter this sphere as providers.

In the last decade, the Russian state has taken measures that significantly change the image of the state as a social state and, in particular, the image of its sphere of production of public welfare. The changes were caused by the expansion of the non-governmental sector of social services due to the entry of such participants as non-profit organizations, social and individual entrepreneurs, and others (Federal law No. 40, 2010; Federal law No. 442, 2013). In the regions, the government created conditions for the development of the service market and the competitive relations of its actors. At the same time, the state is strengthening its control over participants in social services using such mechanisms as service delivery standards, service quality standards, and individual programs for social service recipients. The regulations adopted by regional authorities allow the testing of specific mechanisms for the participation of new producers in the market of social services, which include such components as registers of socially oriented NGOs (SO NGOs), service providers, and responsible performers of socially useful services as well as criteria for their inclusion in the registers. The procedure for financing different activities, formed through subsidies and compensations to organizations for their services provided to the population, is accompanied by the development of reporting requirements for non-profit organizations and social entrepreneurs. A special place in the state support of SO NGOs is given to the system of grants for their implementation of social projects (Benevolensky and Shmulevich 2013). These processes are so relevant on the agenda that indicators that show an increase in the number of SO NGOs are considered when assessing the effectiveness of regional management bodies and officials.

In the case of Russia as a social state, new challenges create changes in the demographic structure of the population, which determine the special significance of innovative approaches of social protection for young people. The consequences of the demographic revolution, which Rosanvallon focuses on in her analysis of the causes of the welfare states crisis, influenced the rethinking of existing state models in the 20th century (Rosanvallon 1997, p.38–39). In modern welfare states there is an active policy that not only maintains an acceptable standard of living and income but also creates conditions for the development and realization of opportunities for young people (The Progressive Welfare Mix 2009, p.90). Social states in the 21st century have acquired the character of social-service states and, as Sidorina writes, are distinguished by a “strengthening of individual autonomy, responsibility, development of abilities, expansion and enrichment of the range of individual opportunities. Welfare state becomes a dynamic and progressive welfare mix that combines the capabilities and abilities of different institutions, actors and spheres of modern society” (Sidorina 2010, p.127).

The transition to a new Russian state social policy paradigm is being primarily implemented through the diversity and increase in the range and volume of social services and the focus on improving their quality and accessibility; moreover, it is accompanied by a noticeable growth of non-profit organizations as providers of social services (Starshinova, Borodkina 2020). What is more, both the number of people employed in the non-profit sector and the number of recipients of these organizations’ services have increased (Kosygina 2018).

The transformation of the social welfare system affects the interests of all social groups, including young people. However, the position of young people as recipients of social services is not sufficiently represented in research on the development of the non-governmental sector in the field of social services in Russia. This is largely due to ingrained ideas about social services being a system that functions in the interests of older generations, which is supported by age-related accents in the current legislation (Savinskaya and Istomina 2019, 493). On the other hand, analysis of the Russian regions attracting NGOs as social service providers shows that the priority areas of NGO’ services are education, youth policy, the upbringing and health care of children, and support for young families with children (Romanova et al. 2017; Rudnik et al. 2017). Therefore, the priorities in the social activities of NGOs are directly related to the social needs of various youth groups.

The attitude of young people to receiving social services, their involvement in the sphere of social services, awareness of the opportunities of the NGOs, and their readiness to accept proposed innovations characterize the formation of NGOs in intersectional interaction as a mechanism for implementing modern social policy (Social Policy 2009). At the same time, an analysis of the social service demands of young people as consumers of public goods would be useful for the subsequent development of the non-profit sector and non-state service providers.

The research was aimed at investigating young people as recipients of social services, the preferences of young citizens when choosing between state service institutions and non-governmental providers, and the demand for innovative ways of providing services to young people. The study was based on the assumption that the position of young people concerning the emerging mixed system of social services is differentiated. It depends on intra-group differences and expectations and is also largely determined by trust/distrust in the public service institutions and non-governmental organizations involved in the production of social services.

2 The theoretical background of the research

Young people are a complex, heterogeneous group which is a special, independent consumer subject (Omelchenko 2007). Therefore, contemporary research on young people is very diverse. Among the priority areas of research in Russia are the transformation of the youth space over the past 25 years, new forms of youth sociality and activity (Omelchenko 2019), the peculiarities of the socio-economic situation of Russian youth (Lukyanova and Sabirova 2012), the processes of growing up of working youth, gender aspects and social inequality in the workforce and environment (Walker 2012). In these studies, Russian youth is considered, first of all, as an active social group with its own special way of life and social practices, playing a significant role in the socio-economic, cultural and political space of the modern Russian state. In the theoretical and empirical field of research, no attention is paid to youth as a socially vulnerable category in need of social services. Moreover, at the state level, youth policy and social policy are contextually divided between different departments. Therefore, young people are not singled out in the framework of traditional social policy as the main group of recipients of social services. The priorities of the state youth policy are the development of infrastructure, the formation of value orientations and moral attitudes of young people, support for young families and youth in difficult life situations, and much more (Zubok et al. 2016). But the main problem, according to Russian studies, is that the federal authorities do not form a policy of working with youth, but are focused only on the implementation of a set of measures, which includes support for certain groups of talented young people (Podyachev and Khaliy 2020) without interacting with the system of social services, while the reforms taking place in the welfare state essentially measure the role of youth in modern society.

The concept of the welfare mix system of public goods and the practice of production evolved in response to the search for ways to overcome the “failures” of the market (not meeting the social needs of certain segments of the population) and “institutional failures” (the limited capacity of the state to provide for the special needs of citizens). The theoretical framework of the welfare mix production of public goods includes the concept of sector development, which recognizes the importance of the private and public/non-profit sectors along with the public sector (Johnson 1996; Verschuere et al. 2012). New approaches in the theory and practice of the welfare state stimulated the diffusion of ideas for changing the role of the state in regulating and producing public goods, and the need to combine the efforts of civil initiatives (public/non-profit sector), private resources, and individual efforts to solve social problems (Esping-Andersen 1990; Abrahamson 1995; Abrahamson 1999; Understanding the Mixed Economy of Welfare 2007). In practice, the implementation of new approaches means transferring some of the power of providing social services guaranteed by the state to non-profit and private service actors. So, a special role in forming a social partnership and intersectional interaction in ensuring the social needs of citizens is assigned to non-governmental organizations (Salamon and Toepler 2015).

In many international and Russian studies, attention is drawn to the advantages of NGOs as service providers, including their use of innovative approaches to the social problems of the target groups (Krasnopolskaya and Mersiyanova 2015; Ludwinek et al., 2013). The interest in studying young people as consumers of social services is also determined by their ability to respond quickly to innovations. Due to the subject of our analysis, it is important to discuss the increasing complexity of the role of service recipients in the emerging environment, their relationships with different providers of public services, and their expectations (Clarke 2011; Stan 2007). For countries with mixed welfare, it means, as Clarke (Clarke 2011) said, “a reinterpretation of the mixed model of the welfare state”. In the Russian context, the discussion of this issue at the stage of the formation of new relationships in the social services system contributes to the timely implementation of the preventive potential of young people. According to the functional approach, the expansion of the range of services, and their availability in accordance with specific age requirements and stages of socialization in mixed welfare state contribute to the expansion of the acceptable ways young people can choose to integrate into society (Starshinova 2019).

The factors determining the development of new participants in the production of public goods include public confidence (Bobkova 2014; Reutov 2018). Trust is considered one of the grounds of social integrity and is associated with the reciprocity of expectations of interacting social actors, and it is one of the key characteristics influencing their behavior. In contemporary theories, the phenomenon of trust as a condition for the stability of the social system but differentiate between personal and institutional trust (Giddens 1990, Luhmann 1979, Eisenstadt & Roniger 1984, Seligman 2000, Sztompka 1999). Trust could be interpreted as component of social capital through which social relations are reproduced (Coleman 1988): Giddens, considering the value of trust in interpersonal relations, analyzes the mechanisms of its formation (Giddens 1990). Luhmann’s understanding of the trust/distrust dichotomy, which is a way of overcoming the difficulties of choice when making decisions in conditions of information scarcity, is important (Luhmann 1979).

The theory of trust by Sztompka, where trust is understood primarily as a factor in relation to future unforeseen actions of others (Sztompka 1999) was also taken into account. According this approach, trust is not only an interpersonal construct, but can be extended to attitude towards social institutions, forming institutional trust. And in this context, the attitude of youth to state social services and NGOs is an indicator of the level of trust to welfare state institutions in general. On the other hand, it is young people, possessing the necessary potential for civic activities, who can be considered as a key social group capable of influencing the spread of a culture of trust. The developing of personal and social capital, the building up of resources by certain social groups, and young people in the first place, allows us to overcome the distrust characteristic of post-socialist countries (indicated by Sztomka), and for Russia as well.

According to previous sociological studies, non-governmental organizations aroused the least institutional trust among Russians (Sasaki, Davydenko, and Latov 2009, p.29). In research on trust/distrust in the development of civil society, it was noted that the population’s distrust of the activities of domestic NGOs was associated with the closeness of their activities. However, “the state’s actions to create favorable conditions for the activities of NGOs can stimulate the openness of NPOs and the openness of the third sector, and the availability of information about it to the population” (Trust and Distrust 2013, p.13). Thus, influencing the behavior patterns and expectations of young people in relation to social services, as well as building trust in non-governmental providers, can become a development resource for NGOs.

3 Research methods

The design of the study included quantitative methods of collecting empirical data: telephone and street surveys. Data was collected in Autumn 2019 in two major cities, Yekaterinburg and Saint-Petersburg. The total sample size was 1,204 persons, including 438 young people aged from 18 to 35. The sample type is quota sampling based on socio-demographic and territorial characteristics. Quotas were calculated on the basis of official statistics on a number of gender and age groups living in different administrative regions of these cities. Compliance with quotas was strictly controlled at the fieldwork stage, and the results of the control were carried out to repair the sample. The telephone survey in Saint Petersburg (702 persons, 240 young people aged from 18 to 35 years old) was conducted on the basis of the Resource Center’s «Center for Sociological and Internet Research» of Saint Petersburg University using the “Computer Assisted Telephone Interview” system and a random selection of phone numbers among housing stock and mobile operators. The collection of empirical data in Yekaterinburg (502 persons, 198 young people aged 18-35 years) was carried out in the format of a street survey conducted at several points of mass congestion of citizens in different districts of the city.

In both cities, empirical research was conducted on a single questionnaire. The blocks of indicators included socio-demographic characteristics, the need for social services, experience in receiving social services, satisfaction with the quality of services provided, remote ways of interacting with social institutions, readiness to receive social services in digital form, and the level of trust in the state and non-state institutions of the social sector. The results of the investigation were processed in SPSS Statistics 26.0 with using K‑means cluster analysis, correlation analysis, and descriptive statistics.

4 Research results

4.1 Main groups of youth as consumers of social services

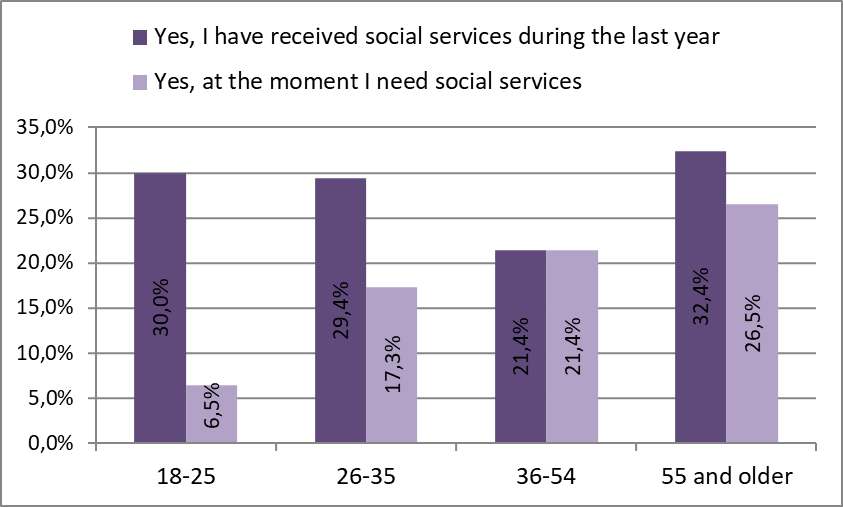

Young people as consumers of social services is a special category among all client groups. According to our data, 27.8% of respondents of all ages had received social services over the past year. In figure 1, you can see that the percentage of young people who have used social services over the past year is even higher than in the age group of 36-54 (see Figure 1.).

Figure 1. The need for social services and experience of consumption of social services (answers to questions: 1. Have you or any of your relatives received social services in the past year? and 2. Do you currently need any social services? The asymptotic significance of the Pearson’s сhi-squared test is 0.005 and 0.000, respectively).

However, a detailed analysis shows that to “social services”, respondents attributed a wide range of socially useful and public services such as applying to medical educational institutions, pension funds, multiservice centers, receiving child benefits and coupons for dairy products, issuing a passport through public services, obtaining various certificates, paying state duties online, etc. 82.5% of the respondents aged 18-35 stating that they had used social-health services refer to clinic visits, treatment in medical hospitals, having testing/dispensary, etc., which indicates an ignorance of specific socio-medical services and the substitution of the concept of “social service”.

The subjective need for social services is minimal in the age group of 18-25 (6.5%) and increases in the age group of 26-35 (17.3%). The selected indicators most likely demonstrate the actual number of potential recipients of social services in the selected youth subgroups. The majority of the respondents aged 25-35 have children and elderly parents and have possibly acquired disabilities, chronic diseases, and family problems, which increase the risk of difficult life situations that they cannot manage with their own resources.

Within the “youth” client group, clusters were identified, differentiated by socio-demographic characteristics, needs and the experience of receiving social services, readiness to receive social services in a digital form, and the level of trust in state and non-state institutions of the social sector. The K-means method was used for clustering, convergence was achieved using 12 iterations, the maximum change in the absolute coordinate for any center was 0.000, and the minimum distance between the initial cluster centers was 11.790. As a result of clustering, four consumer segments were formed within the youth group (see Table 1.)

Table 1. Segmentation of young people as clients of social services

|

Segmentation criteria |

|

|

|

|

|

Demographic characteristics of the segment |

Behavioral characteristics of a segment |

Psychographic characteristics of a segment |

The name of the segment |

|

|

Men/women (mostly men) at the age of 23-27 years, working as technical staff with a middle income |

They do not use social services or need them |

High degree of independence and distrust of social institutions |

Non-users “Non-consumers”

Share 27.2% |

|

|

Students of higher and secondary educational institutions of both sexes aged 18-20 years, with average income |

They do not need services but believe that they use them, meaning, in most cases, public and socially useful services |

High significance of reference groups, ability to trust, incompetence in the field of social services, substitution of concepts |

New users “New consumers”

Share 26.0% |

|

|

Men/women over 30, professionals with higher education and middle income |

They believe that they need services, sometimes use them, and are ready to receive social services remotely/digitally |

Advanced consumers who care about status, the need for distinction. They are capable of loyalty, ready for innovation, and active. |

Digital users “Digital consumers”

Share 34.9% |

|

|

Men/women (mostly women) 25-30 years old, with higher or secondary special education, with low-paid jobs or temporarily out of work (including housewives and women on maternity leave) with lower-than-average income |

They need in-services and use services, preferring free services in the traditional form |

People of habit who value security, stability, reliability, and convenience. They are brought up with traditional values, often go with the flow, are not adaptive, and are conservative |

Traditional users “Traditional consumers”

Share 11.9% |

|

A total of 27.2% of the young people who took part in our study are classified as “non-users”. These are mainly young men, who think that traditional values and the demonstration of masculinity have high importance. Seeking help does not correlate with their idea of “the right life” and harms their reputation. Therefore, 97.6% of representatives of this segment say that they do not need social services.

The share of “new users” is 26.0%. This group includes students of various educational institutions who often live with their parents and depend on them. Older relatives are more likely to become clients of social institutions than they are but, if necessary, they will resort to social services to solve their problems. According to subjective feelings, 11.4% of respondents in this segment believe that they need social services and 44.4% are ready to receive them on a paid basis (in full or in part). The most interesting areas of activity in the social sector are employment assistance, leisure activities, and legal advice. Being the youngest segment, they are more likely to use messengers (WhatsApps, Telegram, Viber) to communicate with social service organizations (27%).

“Digital users” includes 34.9 per cent of the young people polled. These are young professionals with higher education in technical and humanitarian fields who value their time, so the level of demand for digital social services is the highest among them (95.4%). In this segment, 15.7% of respondents currently need social services, and 45.8% of young people are ready to receive services on a paid basis (fully or partially). The most popular social services used by this youth group are employment assistance, social services, leisure, and, especially, legal assistance.

The share of “traditional users” is 11.9%. It includes young people who were unable to find employment (or work in low-paid jobs) after graduation, as well as girls who became housewives after marriage and the birth of a child. They are the conservative “new poor” with a low income, ready to become consumers of social services but in the traditional form and without payment. The term “new poor” refers to young people who, after entering adulthood and becoming independent, have a lower quality of life due to the fact that they have missed the opportunity to use the social capital of their parents but have not yet increased their own. The share of demand for social services in this segment is the highest (23.1%), and the majority (75.0%) are not prepared to pay for them. The most popular social services used by this group are urgent social services, social support, and psychological and legal consultations.

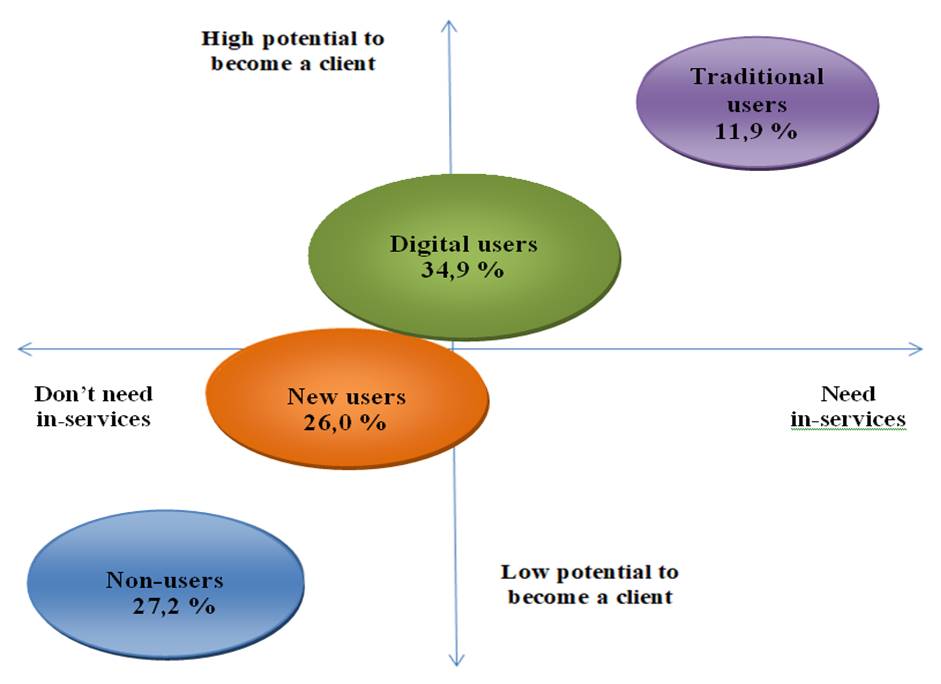

The segmentation map allows a visual assessment of the size of the client groups of young people and their place in the structure of the client base of social institutions (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. The need for and consumption of in-social services

The customer segments we have identified show differences in behavioral and psychographic characteristics. If we consider young people as potential recipients of social services, then social institutions need to consider this specificity in order to plan their activities for each segment.

Moreover, when choosing service technologies for particular segments of youths, social institutions should understand that the overall goal of working with young people in social service organizations is to develop social competence because young people potentially or actually become recipients of services depending on the stages of socialization and the problems that arise when providing solutions. “A feature of social institutions for young people is that they break the stereotypes associated with the traditional concept of social support of the population, the core of their work is, primarily, the social education of the young, the multilateral aid and support those in need, openness to the constant changes of society”, the authors of a study of working with youth underline (Yarskaya at el., 2004, p. 31). In general, we agree with this approach; however, it is necessary to adjust the position expressed to consider the ongoing changes in the sphere of social services. Modern social education does not mean only the development of knowledge but also, and mostly, the development of skills and abilities to find and apply the necessary knowledge, achieving positive changes in the existing life circumstances associated with the restoration of the ability to meet needs independently. The position of the “service recipient” (or service consumer) in accordance with the approved concepts, including the accepted legal norms, in contrast to the “client” of the social service, assumes a certain personal activity in response to the benefits offered by society. This is the root cause of changes in the content of the work of service organizations that provide services to young people and the need to differentiate service delivery technologies.

NGOs currently provide social services for the youth groups that are not able to access state service institutions due to the strict attachment to the standards designed for certain “categories” of service consumers and “packages” of services and approved by regional social service management bodies. NGOs and social entrepreneurs are characterized by their individual approaches and are more sensitive to youth requests. The youth segment, which we have designated as “non-users”, may become recipients of the services of non-profit organizations provided they are focused not on “problems” but on the development of competencies that allow young people to function successfully in the current uncertainty due to rapid social changes. The technologies used to provide services to this youth group should replace the unacceptable image of a “helpless” recipient of assistance with a confident young person who knows how to act thanks to the services received.

The aspect of “new users” that non-government suppliers should utilize is their commitment to advanced new-generation digital technologies. The interests of both parties in the preferences of interaction of providing and receiving services coincide because NGOs today are interested in reducing the cost of renting premises, building maintenance costs, utilities, and other similar expenses. They are switching to using online platforms to provide services, promoting crowdfunding and creating crowdsourcing platforms to attract resources to social crowd projects in the interests of their beneficiaries. NGOs are focused on connecting specialists with service recipients in the virtual space, which reflects the particular interest of representatives of the “digital users” segment. Finally, socially oriented NGOs are characterized by a specific resource that creates opportunities not only to retain the “traditional users” as their recipients but also to increase the share of this segment by attracting volunteers, donations from benefactors, and sponsors. This allows socially oriented NGOs to meet the request of this youth group identified during the study for free services.

4.2 The trust of youth in social institutions

The study results clearly demonstrate that the level of trust in non-state social institutions is significantly lower than in state institutions. The average confidence score for public institutions on a scale from 1 to 5, where 1 – completely distrust, and 5 – completely trust, is 3.54 points, and for non- government institutions is 2.51 points (see Table 2.)

Table 2. Level of trust in social institutions in different age groups

|

Age groups |

Public institutions |

Non-governmental institutions |

||

|

Average (on a scale of 1 to 5) |

% of positive responses |

Average (on a scale of 1 to 5) |

% of positive responses |

|

|

18-35 |

3,66 |

58,9% |

2,90 |

29,4% |

|

36-54 |

3,58 |

58,4% |

2,47 |

21,6% |

|

55-69 |

3,31 |

45,7% |

2,02 |

15,8% |

|

70 and older |

3,40 |

48,6% |

1,86 |

14,2% |

|

Total |

3,54 |

55,2% |

2,51 |

23,1% |

It is significant that the confidence of young people in social service institutions is higher than in other age categories (table 2). It is obvious that this is due to the socio-psychological characteristics of young people, their adaptive abilities, interests, value orientations, social status, and life experiences, which were beyond the scope of our study. At the same time, 31.5% of the young people surveyed have interacted with government agencies while only 1.6% have experience with NGOs. E. Giddens (Giddens, 1990, p. 32–33) states that “blind faith”, faith in symbolic signs and expert systems, is the main mechanism for building trust. In other words, the trust of young people in social institutions, especially NGOs, is formed not through personal experience but on the basis of public opinion, the experience of previous generations, and the self-presentation of social institutions in the public space.

The level of satisfaction with the quality of social services provided shows us the opposite picture: satisfaction with services in non-governmental organizations is significantly higher than in public institutions (4.20 and 3.57, respectively) (see Table 3.).

Table 3. The level of satisfaction with the quality of social services provided in different age groups

|

Age group |

Public institutions |

Non-governmental institutions |

||

|

Average (on a scale of 1 to 5) |

% of positive responses |

Average (on a scale of 1 to 5) |

% of positive responses |

|

|

18-35 |

3,60 |

61,6% |

4,28 |

89,3% |

|

36-54 |

3,52 |

57,8% |

4,35 |

76,1% |

|

55-69 |

3,56 |

50,0% |

4,00 |

87,5% |

|

70 and older |

3,62 |

55,4% |

3,25 |

50,0% |

|

Total |

3,57 |

57,3% |

4,20 |

82,2% |

There is the paradox: the level of satisfaction with service in non-governmental organizations among young people is higher but the degree of trust in them is lower. In such a situation it is appropriate to refer to N. Luhmann (Luhmann 1979, p.66), who argued that trust in a system is confidence in its stability and effectiveness. The trend we have recorded shows that residents of large cities have a single positive interaction with non-profit and other non-governmental social organizations. However, there is no trust in the system of non-state social service providers, which needs to be purposefully formed since there are still many negative stereotypes in the public consciousness (see Table 4.).

Table 4. Agreement with statements about the development of the non-state social services sector

|

Statements |

Age groups/, % of respondents accepted the statement |

All age groups |

|||

|

18-35 |

36-54 |

55-69 |

70 and older |

||

|

There may be a lot of swindlers among non-governmental institutions |

79,7% |

84,0% |

86,6% |

80,9% |

82,6% |

|

Non-governmental organizations provide mostly paid services |

81,7% |

78,8% |

78,8% |

61,2% |

77,5% |

|

Development of the non-governmental sector expands the list of social services |

63,9% |

53,9% |

48,7% |

31,6% |

53,7% |

|

Non-governmental organizations are more flexible and friendlier than government organizations |

53,9% |

49,5% |

44,8% |

33,6% |

48,2% |

|

The development of non-state social services will improve the quality of services |

49,3% |

35,3% |

31,5% |

20,4% |

37,8% |

|

Only state institutions can guarantee the quality of social services |

26,9% |

37,7% |

46,6% |

45,4% |

36,5% |

The two main misconceptions about the non-governmental sector are “there may be a lot of swindlers among non-governmental institutions” (82.6% of respondents agreed) and “non-governmental organizations provide mostly paid services” (77.5% of respondents). Young people also share misconceptions about paid services, even more than other age groups. This position dominates in the responses of “non-users” (not consumers), which, of course, does not correspond to reality, demonstrating superficial ideas among young people about the emerging relationship between the state and new participants in the sphere of social services.

At the same time, young people see the advantages of new service providers more clearly, particularly the facts that non-governmental organizations are more flexible and friendlier (53.9%) and the development of this sector can improve the quality of social services (49.3%). This position is more typical of the consumer youth segments “new users” and “digital users”. In general, the dominance of this position among young people indicates their openness, flexibility and readiness to accept non-governmental organizations as new providers of public services.

5 Conclusion

The study findings contribute to the understanding of the development of welfare in Russia, and highlight the existing contradictions, including those related to the situation of young people. On the one hand, Russia's trajectory corresponds to the global trend of transition to welfare service state, including marketization of social support system, that also means development of the non-state sector as social services providers (Borodkina 2020, p.666).

On the other hand, as for youth in the welfare context, its position in Russia today differs from that in European countries. In Russia, there is a gap between youth policy and social policy, which has led to the currently dominant approach, according to which young people are not considered primary consumers of social services. At the same time like in other states it is the youth that can become the driver of the development of the non-governmental sector of public goods production Moreover, we can say that the modern system of mixed-welfare provision is more corresponded to the attitudes of young people. This is indicated by the results of the presented research; in particular, the predominance of young people among the respondents who are confident that new providers could expand the range of social services and improve their quality. Young people make up the majority of the urban population convinced that non-governmental service providers are more client-oriented than state ones. Young people demonstrated the highest level of satisfaction with the services they received in non-governmental organizations. At the same time, the obtained data indicate the internal differentiation of young people as consumers of social services with mobile borders. Expanding the list of social services, primarily by NGO activities, as the most flexible structures, as well as the process of digitalization of the social sphere, will inevitably be accompanied with the involvement of young people in the social services market, both as social service providers and as consumers.

At the same time, the analysis of empirical data shows that youth requests for social services have not yet been sufficiently rationalized. Young people’s distrust of non-governmental suppliers and their shared prejudices about their dishonesty and exclusively commercial orientation are combined with positive statements made by young respondents about social organizations in the non-governmental sector. The lack of understanding of what social services and socially useful services mean indicates that young people do not have a full understanding of the opportunities offered by the emerging welfare mix social service system. The identified contradictory positions of young recipients of social services need to be studied further and can form the perspective of the research topic presented in the article. A closer analysis of these contradictions creates the potential for a discussion about the emerging system of social services and the emerging advantages of new producers to meet young people’s social needs. Certain aspects of consumerism can be seen in social work practice, this also leads to an increasing inclusion of youth in the social system and creating new opportunities to work with different groups of young people. The latter circumstance underlines the need for a widespread information campaign about the fundamental changes in the social services sphere as well as for further research on youth as one of the key actors of mixed-welfare state.

Acknowledgments. The research was conducted in Saint Petersburg University with the support of the Russian Science Foundation, the project №19-18-00246 “Challenges of the transformation of welfare state in Russia: institutional changes, social investment, digitalization of social services”.

References:

Abrahamson, P. (1995). Welfare Pluralism: Towards a New Consensus for a European Social Policy? Current Politics and Economics of Europe, 5 (1), 29-42.

Abrahamson, P. (1999). The welfare modelling business. Social Policy & Administration, 33 (4), 394-415. DOI: 10.1111/1467-9515.00160.

Avtonomov, A. S. & Gavrilova, I. N. (2009). Social policy in the context of intersectoral interaction. Moscow: Main archive Department of the city of Moscow. (In Russ.).

Benevolensky, V. B. & Shmulevich, E. O. (2013). State support of socially oriented NGOs in the light of foreign experience. Issues of state and municipal management, 3, 66-73. (In Russ.).

Bindman, E., Kulmala, M., & Bogdanava, E. (2019). NGOs and the policy‐making process in Russia: The case of child welfare reform. Governance: An International Journal of Policy, Administration and Institutions. 32(2), 207- 222. https://doi.org/10.1111/gove.12366.

Bobkova E. M. (2014). Trust as a factor in the integrity of society. Sociological Studies, 10 (366), 70-75. (In Russ.).

Borodkina, O. I. (2020). Social Work Transformation—National and International Dimensions: The Case of Russia. In Sajid S. M., Rajendra Baikady, Cheng Sheng-Li & Haruhiko Sakaguchi (Eds.), The Palgrave Handbook of Global Social Work Education (pp.657-670). Cham: Palvgrave. Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-39966-5.

Clark, G. (2011). Beyond public and private? Transformation of the mixed welfare model. Journal of Social Policy Studies, 9 (2), 151-168.

Coleman, J. S. (1988). Social capital in the creation of human capital. The American Journal of Sociology, 94(Supplement), 95-120.

Eisenstadt, S. N. & Roniger, L. (1984). Patrons, Clients and Friends: Interpersonal Relations and the Structure of Trust in Society. Cambridge:Cambridge University Press.

Esping-Andersen, G. (1990). The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Federal law No. 40-FZ of 05.04.2010 "About amendments to certain legislative acts of the Russian Federation on the issue of support for socially oriented non-profit organizations". (In Russ.) URL: http://www.consultant.ru/document/cons_doc_LAW_99113/ (accessed: 26.12.2019).

Federal law No. 442-FZ of 28.12.2013 "About the basics of social services for citizens in the Russian Federation". (In Russ.) URL: http://www.consultant.ru/document/cons_doc_LAW_156558/ (accessed: 26.12.2019).

Giddens, A. (1990). The Consequences of Modernity. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Johnson, N. (1996). Mixed Economies of Welfare. Hemel Hempstead: Harvester Wheatsheaf.

Kosygina, K. E. (2018). Topical issues of development of socially oriented non profit organizations. Problems of territory development, 95, 107-121. (In Russ.).

Krasnopolskaya, I. I. & Mersiyanova, I. V. (2015). Transformation of social sphere management: a request for social innovations. Issues of state and municipal management, 2, 29-47. (In Russ.).

Kulmala, M., Rasell, M., & Chernova, Z. (2017). Overhauling Russia’s child welfare system: Institutional and ideational factors behind the paradigm shift. Journal of Social Policy Studies, 15(3), 353–366.

Kulmala, M., & Tarasenko, A. (2016). Interest representation and social policy making Russian Veterans’ organisations as brokers between the state and society. Europe-Asia Studies, 68(1), 138–163.

Ludwinek, A., Sándor, E., Ecker, B., & Scoppetta, A. (2013). Social innovation in service delivery: New partners and approaches. European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions. URL: https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/publications/report/2013/industrial-relations-social-policies/social-innovation-in-service-delivery-new-partners-and-approache (accessed: 10.01.2020).

Luhmann, N. (1979). Trust and Power. Chichester: Wiley.

Lukyanova, E.L. & Sabirova, G.A. (2012). "The crisis is somewhere in parallel": features of the study of young people in an economic downturn, Sociological Studies, 5, 79-88. (In Russ.).

Omelchnko, E. L. (2007). Youth of Russia: from XX to XXI century. Vestnik of Lobachevsky State University of Nizhni Novgorod. Series: Social Sciences, 3(8), 82-87. (In Russ.).

Omelchenko E. L. (2019) Is the Russian case of the transformation of youth cultural practices unique?. Monitoring of Public Opinion: Economic and Social Changes, 1, 3-27. (In Russ.) https://doi.org/10.14515/monitoring.2019.1.01.

Order of the Government of the Russian Federation No. 768-R 17.04.2019 "Standard for the development of competition in the subjects of the Russian Federation". (In Russ.) URL: http://pravo.gov.ru/proxy/ips/?docbody=&prevDoc=102378143&backlink=1&&nd=102543701 (accessed: 12.05.2020).

Podyachev, K.V. & Khaliy, I.A. (2020). State youth policy in modern Russia: concept and realities. RUDN Journal of Sociology, 20 (2), 263-274. (In Russ.) https://doi.org/10.22363/2313-2272-2020-20-2-263-276.

Powell, M. A. (2007). Understanding the mixed economy of welfare. Bristol: The Policy Press.

Reutov, E.V. (2018). Factors of the formation of social trust and mistrust in modern Russian society. Central Russian Journal of Social Sciences, 13(1), 12-20. (In Russ.) https://doi.org/DOI: 10.22394/2071-2367-2018-13-1-12-20.

Romanova, V. V. & Khanova, L. M. (2017). Certain aspects of the development of the mechanism of state subsidization of NPOs in the context of the subjects of the Russian Federation. Finance: theory and practice, 21(6), 128-137. (In Russ.).

Rosanvallon, P. (1997). The New social question. Rethinking the welfare state. Moscow: Ad Marginem. (In Russ.).

Rudnik, B. L., Kushtanina, E. V., & Romanova, V. V. (2017). Involvement of NGOs in the provision of social services. Issues of state and municipal management, 2, 105-127. (In Russ.).

Salamon, L.M. & Toepler, S. (2015). Government-Nonprofit Cooperation: Anomaly or Necessity? Voluntas, 26 (6), 2155–2177.

Sasaki, M., Davydenko, V. A., Latov, Yu. V., Romashkin, G. S., & Latova, N. V. (2009). Problems and paradoxes of analysis of institutional trust as an element of social capital in modern Russia. Journal of institutional research, 1(1), 20-35. (In Russ.).

Savinskaya, O. B. & Istomina, A. G. (2019). Spatial construction of social services for families with children. Journal of Social Policy Studies, 17(4), 491-506. (In Russ.) https://doi.org/10.17323/727-0634-2019-17-4-491-506.

Seligman, A. B. (2000) The Problem of Trust. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Sidorina, T. Yu. (2010). Partnership of the State and Institutions of Self-organization of Citizens in the Implementation of Social Policy (Theoretical Aspect). Terra Economicus, 8(1), 117-129. (In Russ.).

Stan, S. (2007). Transparency: Seeing, Counting and Experiencing the System. Anthropologica, 49(2), 257-273.

Starshinova, A. V. (2019). Contradictions of students’ motivation for participation in the activities of voluntary organisations. The Education and Science Journal, 21(10), 143-166. (In Russ.) https://doi.org/10.17853/1994-5639-2019-10-143-166.

Starshinova A. V. & Borodkina O. I. (2020). NGOS’ activities in social services: public expectations and regional practices. Journal of Social Policy Studies, 18 (3): 411–428. (In Russ.) https://doi.org/10.17323/727-0634-2020-18-3-411-428.

Sztompka P. (1999). Trust: a sociological theory. Cambridge.

The progressive welfare mix. Responses to the global crisis: charting a progressive path. Handbook of ideas. Progressive governance. (2009). Chile: Policy Network. URL: https://eml.berkeley.edu/~eichengr/responses_global_five_ideas.pdf (accessed: 15.05.2020).

Kupreychenko, A. B. & Mersiyanova, I. V. (Eds) (2013). Trust and Distrust in the Development of Civil Society. Moscow: Publishing House National Research University Higher School of Economics. URL: https://publications.hse.ru/mirror/pubs/share/folder/ccb5sg6w5f/direct/117877287 (accessed: 15.05.2020).

Verschuere, B., Brandsen, T., & Pestoff, V. (2012). Co-production: The State of the Art in Research and the Future Agenda co-production of public services. Voluntas, 23, 1083-1101.

Zubok Yu. A., Rostovskaya T. K., & Smakotina N. L. (2016). Youth and Youth Policy in the Contemporary Russian Society. Moscow: ITD Perspective (In Russ.).

Walker, C. (2012). Class, gender, and subjective well-being in the new Russian labor market: the life experience of young people in Ulyanovsk and St. Petersburg. The Journal of Social Policy Studies, 10 (4), 521-538.

Yarskaya, V. N., Yakovlev, L. S., Slepukhin, A. Yu., Petrov, D. V., Dobrin, K. Yu., & Baryabina, E. N. (2004). Sociology of youth in the context of social work Saratov. Federal educational portal "Economy. Sociology. Management". (In Russ.) URL: http://ecsocman.hse.ru/text/19197291/ (accessed: 01.05.2020).

Author´s

Address:

Alevtina V. Starshinova

Ural Federal University, Russia

a.v.starshinova@urfu.ru

Author´s

Address:

Olga I. Borodkina

Saint Petersburg University, Russia

oiborodkina@gmail.com

Author´s

Address:

Elena B. Arkhipova

Ural Federal University, Russia

e.b.arkhipova@urfu.ru