Aftercare support in Norway - Barriers to support?

Inger Oterholm, VID Specialized University Oslo

1 Introduction

Support in the transition to adulthood is important to children in out-of-home placements. Research indicates that aftercare support leads to better outcomes for these young people, including higher levels of education and less unemployment or need for financial assistance benefit (Backe-Hansen et al., 2014; Courtney et al., 2011; Everson-Hock et al., 2011; Munro et al., 2012). These young adults also are more likely to have someone from whom to seek support, improved financial prospects, and a reduced risk of homelessness (Courtney, 2019; Courtney et al., 2011; Courtney, Okpych, & Park, 2018).

The outcomes for care leavers in Norway resemble those in other countries: These youths are less likely to be educated and employed and more likely to receive financial assistance benefits than young people without a care background (Backe-Hansen, Madsen, Kristofersen, & Sverdrup, 2014). They also are more likely to have physical and mental health problems (Lehmann, Havik, Havik, & Heiervang, 2013). The prevalence of similar observations from other countries points to the importance of aftercare support for care leavers (Berlin, Vinnerljung, & Hjern, 2011; Brännström, Forsman, Vinnerljung, & Almquist, 2017; Courtney et al., 2011; Gypen, Vanderfaeillie, De Maeyer, Belenger, & Van Holen, 2017; Olsen, Egelund, & Lausten, 2011; Stein, 2012).

In Norway, a nationwide audit (Statens Helsetilsyn, [Board of Health Supervision] 2020) and a recent study of aftercare (Paulsen et al., 2020) highlight a need for improvement in several aspects of support for care leavers. For example, the audit pointed out regulatory breaks in 27 (55%) of the 49 municipalities investigated (Statens Helsetilsyn, 2020), suggesting that young people are not receiving the necessary support to which they are entitled. The aftercare study found that a relatively low proportion of those who could potentially receive aftercare, get aftercare. The analysis gave clear indications that many aftercare measures are terminated without a thorough assessment of needs and due to causes other than the needs of young people (Paulsen et al., 2020). These findings suggest a crisis in provision of aftercare support.

To explore further the aftercare situation in Norway, the following research question is posed: What barriers to aftercare - if any - do young people who received support from Norwegian child welfare services encounter?

To answer this question, the article builds on several studies of aftercare in Norway (Oterholm, 2008, 2015; Paulsen et al., 2020; Statens Helsetilsyn, 2020) from 2008 to 2020 and discusses the findings in light of Butler’s (2004, 2010) theory of the precariousness and grievability of life. Butler argues that society does not equally recognize people’s lives as grievable; that is, people are framed in different ways and tend to count differently. Butler’s theoretical perspective illuminates how young people who are exiting the child welfare system may be categorized and framed, and in turn, raises the question of whether these youths are no longer recognized as children, and thus, are relegated to the outskirts of the child welfare services’ responsibility and downgraded as recipients of support.

2 Out-of-home care and aftercare in Norway

In 2019, just under 55,000 children and youth in Norway received support from child welfare services (Statistics Norway, ssb.no). About 9,700 were placed in out-of-home care, while approximately 44,800 received in-home services, which represents a small decline from the previous year.

The Child Welfare Act (1992) states that assistance initiated before the child reaches age 18 may be maintained or replaced by other types of assistance until the individual is age 23. In 2021, the eligibility for aftercare support was extended to age 25. Aftercare in Norway is part of the regular public child welfare services in the municipalities. As of 2020, there were 356 Norwegian municipalities, most with their own child welfare services (local authorities), but some with inter-municipal collaborations. As municipalities differ in area and population size, so do local child welfare services, and aftercare support is organized in ways that local authorities consider best.

Before children reach the age of 18, child welfare services must inform the young person about the possibility of aftercare. Child welfare personnel must complete an overall needs assessment, cooperate with the youths, consider their wishes, and obtain their consent for aftercare (Child Welfare Act, 1992). The specific aftercare support provided is left to a social worker’s discretion, but the support must be justified as in the best interests of the child.

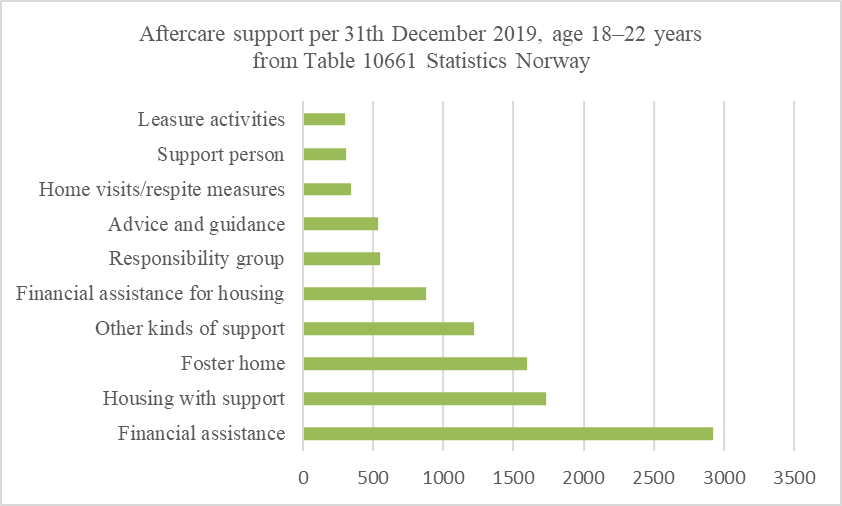

A wide range of measures fall under the umbrella of aftercare support. The 10 most common are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1

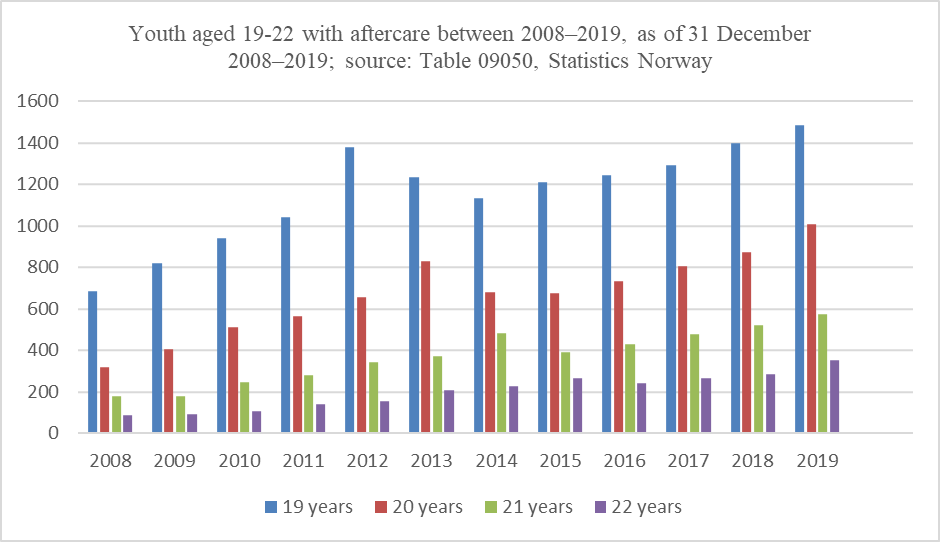

Financial assistance, housing, and continued foster care have been the most common aftercare support for many years (Statistics Norway). In addition, the number of youths receiving aftercare has increased in the last decade, according to Statistics Norway, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2

Aftercare support increased for all youths 19 and older from 2008 to 2019[1], but very few youths were supported until age 23. Between two-thirds and one-half stopped receiving aftercare between the ages of 19 and 20, and even fewer received support in their twenties. Although the number receiving aftercare support increased, the proportion did not; only approximately 20% of those who received earlier child welfare services received aftercare (Paulsen et al., 2020).

In an ongoing effort to amend the Child Welfare Act, the Ministry of Children and Families sought to clarify the right to aftercare, and has proposed that to receive assistance, young people must have “special needs for help from child welfare services to make a good transition to adulthood.” “Special needs” for support are defined as those beyond what young people in general would have (Barne- og likestillingsdepartementet, 2019, p. 100). The general population of kids may have considerable help from their families, which child welfare kids do not. Consequently, if aftercare is even further restricted to “special needs,” then these kids end up with even less. This proposal may lead to young people with a child welfare background having fewer opportunities than other young people to receive support in the transition to adulthood. Typically, young people receive support from their parents well into adulthood (e.g. Hellevik, 2005; Manzoni, 2018; Swartz & O'Brien, 2009).

3 Methodology

3.1 Introduction

To answer the research question, I drew upon several studies concerning aftercare in Norway: a survey of child welfare services (Oterholm, 2008, 2009), qualitative interviews with social workers (Oterholm, 2015), the most recent research on aftercare support in Norway (Paulsen, 2020) and a nationwide audit (Statens Helsetilsyn, 2020).

These studies represent important contributions to aftercare research over several years and using different methodologies. Data from several significant studies over several years can reveal trends within aftercare support in Norway and barriers to that support. The survey (Oterholm, 2008), which is the only one on aftercare support across all of Norway’s child welfare services, offers an overall picture of Norwegian aftercare practice. In addition, the interview study (Oterholm, 2015) is the only one focusing on social worker’s considerations related to aftercare and points to reasons that aftercare is (or is not) provided. The “aftercare study” (Paulsen et al., 2020) is included because it is the most recent aftercare study in Norway and is based on different methodological approaches. Finally, the latest nationwide audit of aftercare in Norway is included (Statens Helsetilsyn, 2020). The methodologies of each of these studies are described in the next section.

3.2 The studies and their methodologies

The survey (Oterholm, 2008, 2009), which was distributed to all child welfare services asked the main research question: How do the child welfare services follow up with young people who have been in care during their transition from care to an independent life? The data included 30 sets of written guidelines, representing about half of the services that reported having written guidelines. The services were asked about their aftercare practices, their organizations, and reasons for giving or not giving aftercare support to young people leaving care. Sixty-eight per cent of the services responded to the survey, including small and large services, in big cities and rural areas throughout the country, and with different ways of organizing aftercare support. The data were coded in the statistical program, SPSS, and analyzed largely using frequency distributions.

The interview study, which focused on aftercare practices in child welfare services (Oterholm, 2015), included 15 social workers who were selected using strategic sampling procedures to ensure variation (Mason, 2002). The interviewees represented services from different parts of Norway, with different numbers of employees and different ways of organizing their services. The study utilized vignettes, which are especially useful for obtaining knowledge about professionals’ considerations, and a qualitative design to allow for exploration of which circumstances are pertinent (e.g. Barter & Renold, 1999; Monrad & Ejrnæs, 2012). Each social worker was asked to comment on five different vignettes about youth aging out of care. The data were coded using the qualitative data management program, NVivo. To ensure a systematic process, analytical questions were used to evaluate the material in its entirety (Kvale & Brinkmann, 2009).

In their recent study of aftercare, Paulsen et al. (2020) asked: Does the current aftercare arrangement contribute to a good transition to adulthood for youth with a child welfare background? The study used a combination of research methods, including quantitative analysis of national register data; qualitative interviews in a selection of municipalities with 57 social workers from child welfare services and 70 young people with child welfare experiences; and an analysis of 40 child welfare records from three municipalities.

The nationwide audit of aftercare practices was conducted by the county governors of Norway on behalf of the Board of Health Supervision (Statens Helsetilsyn, 2020). Inquiries were carried out to determine whether the services provided adequate information, whether they facilitated user participation, and whether the assessment of cases was satisfactory. The county governors conducted the sampling of municipalities and child welfare offices based on their knowledge of the counties and risk assessment; as such, the sample was not representative. The audit was conducted through interviews with employees and young people and analysis of child welfare records and other documents in the services.

3.3 Analyzing the data

A secondary analysis or re-analysis involves asking new questions and looking for new interpretations of the material (Bishop, 2016). For this article, I re-analyzed the selected studies in light of the research question—namely, whether barriers to aftercare exist for care leavers in Norway and, if so, what those barriers are.

First, I read the research reports to obtain an overview of the data and then re-read them to identify the main themes related to possible barriers to aftercare support in all or most of the studies. I used the research question to guide the analyses of all the material in order to ensure a systematic approach (Kvale & Brinkmann, 2009). Specifically, I examined the studies with a focus on whether or not barriers to support were described, coding any barriers close to the empirical data and then grouping them by themes. As Braun & Clarke (2006) described, such themes can represent patterns within the data. I identified the following themes representing barriers to support: prioritization in child welfare services; consent to and conditions for assistance; organizational barriers; and the possibility of transfer to adult services. I then examined these themes in light of Butler’s (2004, 2010) theory of the precariousness and grievability of life and how people are framed differently. Her theoretical concepts help to reveal the consequences of these barriers that limit the possibilities for support in the transition to adulthood.

3.4 Limitations

For the re-analysis, I utilized only the published data from the original studies, which is an excerpt of the original datasets. The research question has a different focus than the original studies; nevertheless, the studies provided data relevant to the topic of this article. However, I excluded conditions that could act as barriers, such as lack of participation, if they were at theme in only some of the studies. Also, with a focus on barriers, I gave little attention to examples of good aftercare practices in the studies. Finally, the differences among the studies can lead to a “muddled” methodological approach; therefore, in the interest of transparency, I briefly described each study’s methodology (above) and included a number of citations when presenting the findings.

4 Theoretical perspective

American sociologist and philosopher Judith Butler’s concepts of precariousness and grievabilty are useful for understanding this study’s findings (Butler, 2004, 2010). Building on the work of Emmanuel Levinas, French philosopher, among others, Butler developed an ethical theory that describes human life as precarious. Precariousness is a condition that human beings share by virtue of being born; moreover, because, as living beings, we can die, we are dependent on others to survive: “Precariousness implies living socially, that is, the fact that one’s life is always in some sense in the hands of the other” (Butler, 2010:14). Butler’s conceptualization of precarity seems especially relevant to youth who have been in care and experienced trauma and loss (Boddy, Bakketeig, & Østergaard, 2019). These youths have experienced the failure of those upon whom they were dependent, and thus must depend on the state and social workers acting on behalf of the state as they transition to adulthood.

Butler (2004, 2010) used the concept of grievability to describe how lives are recognized as precarious through how their loss is grieved. Using the “war on terror” as an example, she described how American victims of 9/11 received considerable individualized attention, while civilian victims in Afghanistan had neither names nor faces in the American media. The Afghans, she argued, were not counted as lives, and as such were not grievable. As grievability is a condition for lives that count, certain lives are highly protected while others - those that do not qualify as grievable - are less so; therefore, according to Butler, grievability is unevenly distributed.

Butler’s concepts also have been used in other contexts. For example, undocumented refugees may be framed as less grievable (Stålsett, 2012), and categorization processes in social work frame some people as deviant and thus less grievable. Also, Herz (2016) argue that individuals who break with dominant norms risk that their lives will be counted as less grievable.

In this article, Butler’s concepts are drawn upon to capture the precariousness of youth as they transition to adulthood. Her thinking also helps us to understand how youth may be framed differently once they turn 18, and how those frames may be related to grievability.

5 Findings

Several barriers to aftercare support emerged from the re-analysis of data from the four studies (Oterholm, 2008, 2015; Paulsen et al., 2020; Statens Helsetilsyn, 2020). The following barriers were present in most or all of the studies and aligned with four themes: prioritization in child welfare services; consent to and conditions for support; organizational barriers; and possibility of transfer to adult services.

The findings are presented chronologically with data from 2008 to 2020.

5.1 Prioritization in child welfare services

Prioritization was related to the child’s age and earlier support from child welfare services.

Children as a priority

In the survey (Oterholm, 2008), some social workers noted in comments that their huge caseloads sometimes caused them to downgrade youth as a priority. Several commented that they had too little time and too little capacity to follow up with young people as they transitioned to adult life.

Several social workers in the interview study (Oterholm, 2015) also mentioned that younger children received a priority. For example, Susann said:

“It is not mentioned anywhere, but there is a certain amount of resources (…) When one has to prioritize, let’s say we have a child of 2 years and a youth of 20 years, that youth can also get help from other services. (…) Simultaneously, in my opinion a lot of child welfare resources are wasted if you do not have good aftercare” (Oterholm, 2015, p. 198)[2].

Even a social worker, Mari, who was specifically responsible for aftercare, said:

“We still see that some of the aftercare work slips. In a busy day it may be the young people who are moved down the list. It was not time for a visit because there was too much to do. They could have received better help” (Oterholm, 2015, p. 197).

Although social workers considered support necessary, younger children were given priority over youth. The aftercare study by Paulsen et al. (2020) echoed this theme. Social workers described the challenge of finding enough time to provide aftercare support and said that such follow-up was often downgraded, especially in hectic times: “The whole time we have to prioritize. The management want us to end aftercare support as fast as we can” (Paulsen et al., 2020, p. 47). The study revealed that aftercare support was not well-structured, not focused, and not prioritized. “Several describe that focus on early intervention is dominant, and that it is more difficult to argue for increased resources to follow up with young people” (Paulsen et al., 2020, p. 48). The authors noted the focus on young children, investigations, and compliance with deadlines.

Prioritizing early intervention and younger children in child welfare services is understandable because of the risk these children face when exposed to abuse and neglect. Nonetheless, this focus may become a barrier to support for youth needing help in their transition to adulthood. Using Butler’s (2004, 2010) concept of grievability as a lens, we see that this prioritization could reflect the perception that young people are in a less precarious situation and thus less grievable than younger children.

Priority to youth in care

In Norway, youths who receive in-home services may also be eligible for aftercare support, as specified in policy documents:

“It is not a condition for receiving aftercare that the individual youth has been in out-of-home placement. Those who have benefited from voluntary assistance measures pursuant to § 4-4 can also apply for the maintenance of the established support, or about other measures” (Ot.prp. no. 69 (2008–2009) p. 39).

Youths living at home with support from child welfare services seem to struggle more than might be expected, based on the assistance they receive. In other words, they may need more help than they are receiving. Many struggle in school, even more so than youths living in foster homes (Valset, 2014), and also often have significant mental health challenges (Iversen, Havik, Jakobsen, & Stormark, 2008).

As the survey (Oterholm, 2008) was related to support for youths in out-of-home placement, youths with in-home support were not mentioned; however, in the interview study (Oterholm, 2015), social workers underlined their responsibility for youths in care as opposed to those receiving in-home services. Sofie’s comment was typical:

“I think we feel more responsible for youth in care. They are entirely our responsibility. I think I can say that it is easier for them to get aftercare than for those with support living at home” (Oterholm, 2015, p. 171).

Both the qualitative interviews with social workers and a review of case records in the aftercare study (Paulsen et al., 2020) revealed similar findings. Those who received aftercare were primarily youths in foster or residential care, and support for young people living at home seemed to terminate automatically when they reached 18. This finding may be related to the fact that the child welfare employees did not specifically focus on aftercare for young people who have received child welfare services while living at home, as aftercare support was more standardized when young people are in care.

The nationwide audit of aftercare (Statens Helsetilsyn, 2020) indicated similar gaps in aftercare support. Several child welfare services reported that youths receiving in-home services did not receive aftercare, and in some cases, measures were terminated on the grounds that the youths had turned 18. Regarding such cases, the Board of Health Supervision made the following statement:

“However, the audit has shown that in several places there is a systematic difference between young people who have been in a foster home and young people who ‘only’ have had support while living at home. This practice is based on a serious misinterpretation of the Child Welfare Act and deprives many young people of the right to the aftercare that they need” (Statens Helsetilsyn, 2020, p. 19).

The Board of Health Supervision emphasized that such a misinterpretation of the Child Welfare Act may lead to several significant errors in work related to aftercare. Many youths do not have their needs assessed and thus lose their right to support and face barriers to receiving aftercare.

According to Butler (2004, 2010), the way that individuals’ lives are framed has a bearing for whether their precariousness is recognized, and in turn, their lives are counted as grievable. The higher priorities assigned to children and youths by child welfare services indicates different ways of framing their lives. Children are framed as more precarious than youths, and youths in care more precarious than youths with support but living with their families of origin. In turn, this categorization implies different degrees of responsibility from child welfare services, and that some youths do not get the support they need.

5.2 Need for consent and setting conditions for receiving support

At 18, young people reach legal age and are no longer subject to care orders; they must decide on their own whether to receive continued support. A young person’s consent is required for aftercare support, yet young people can be ambivalent about support and want to manage on their own. Also, they may have difficulty understanding or articulating their needs.

In the survey, the most common reason (91%) for not providing aftercare support was that the youths did not want help (Oterholm, 2008, 2009). While some young people may not in fact have needed help, the social workers believed that most of them did, even if the youths refused it. Another common reason why care leavers did not receive aftercare support was that child welfare services and care leavers disagreed on the kind of support needed and the conditions for support. Indeed, 70% of the services indicated that young people did not receive aftercare because of disagreement about the content of the support and that the youths wanted only financial assistance (Oterholm, 2008).

In the interview study, social workers often mentioned that young people had to meet certain requirements to receive support (Oterholm, 2015):

Vibeke: “If they just want to get money, get the rent covered and nothing else, they do not want any follow-up, no contact with the case worker, then we will negotiate and set some requirements or conditions for them to get support” (Oterholm, 2015, p. 230).

Another social worker pointed to common conditions set by the child welfare services:

Heidi: “There are also some conditions on our part. Among other things, you should have a daily activity, whether it is a job, school or whatever it is, courses or something like that. We set that as a requirement” (Oterholm, 2015, p. 233).

In the aftercare study, several municipalities reported setting conditions for support (Paulsen et al., 2020) to which young people must consent to reach an agreement with child welfare services:

“In the interviews with employees, it appears that several of the municipalities set as a condition for aftercare that the young people had a daily activity. This can be, for example, school, work or other special arrangements” (Paulsen et al., 2020, p. 77).

In addition to a daily activity, young people also had to meet conditions related to alcohol and drug use and to commit to remaining in contact with the child welfare service (Paulsen et al., 2020).

Similarly, the nationwide audit (Statens Helsetilsyn, 2020) revealed certain conditions that child welfare services set in order for young people to receive aftercare. The audit reported examples in which support was terminated when the conditions were not met, without an assessment of the youth’s overall situation or whether the termination support was in the youth’s best interest. The audit noted that setting conditions is a serious misinterpretation of the Child Welfare Act, stating:

“There is not an opportunity to set conditions for aftercare support. If a young person needs aftercare, this must be offered without setting requirements” (Statens Helsetilsyn, 2020, p. 28).

The re-analysis of the studies indicated a tradition of setting conditions for receiving aftercare, even though the Board of Health Supervision, the authority that supervises child welfare services, does not support the practice.

Setting conditions may create barriers for young people to access support, barriers that are not found solely in Norway. For example, a distinction exits in some countries between youths who are pursuing education and those who are not. In England, care leavers are usually entitled to support up to age 21, but for young people pursuing education, support can extend to age 25 (Boddy, Lausten, Backe-Hansen, & Gundersen, 2019); however, those who have left education are perhaps those who need aftercare the most.

The transition to adulthood brings another meaning to support: The individual is no longer considered a child in need, but an adult who can exploit the services. Thus, setting requirements for aftercare may be an expression of society’s ambivalence around providing support to young people lest it foster dependency on the state (Courtney et al., 2016; Höjer & Sjöblom, 2011; Oterholm, 2015). Using Butler’s (2004, 2010) notion of framing, we can see that not only are young people framed differently than children, but in turn, support is defined differently for the two groups. For the child, support is not conditional; but restrictions apply for the young person, and support takes on a different meaning as youths reach 18. With adulthood, support changes in a sense from a positive to a negative—something reserved for those who behave according to dominant norms. If framed as deviant, the young person risks not being counted as grievable (Herz, 2016).

Still, both the guidelines (Barne- likestillings- og inkluderingsdepartementet, 2011) and the preparatory work for the Child Welfare Act (Ot.prp. nr. 61 (1997–1998)) emphasize the importance of flexibility as young people transition to adulthood. They recognized the possibility that young people, while still under age 23, may change their minds after initially refusing aftercare support. Young people who earlier did not meet the conditions for support can receive a new opportunity. In fact, young people who initially refuse continued support should be contacted one year after all support has ended to reassess their decisions (Barne- likestillings- og inkluderingsdepartementet, 2011; Barne- og likestillingsdepartementet, 2008). This guideline ensures that young people have the opportunity to receive support, as they may find it difficult to contact child welfare services themselves. However, the studies showed that these follow-up measures are challenging to accomplish. Routines and satisfactory practice are lacking in this area (Oterholm, 2008; Paulsen et al., 2020; Statens Helsetilsyn, 2020).

5.3 Organizational barriers

Organizational barriers are those that arise from provisions in the Child Welfare Act or local guidelines.

Variation in time limits for re-establishing support

Official state policy notes that support should be based on assessments of the young person’s need rather than time-based deadlines (Ot.prp. nr. 61 (1997–1998)); however, deadlines are set, which represent another barrier to receiving aftercare.

In both the survey and the interview study (Oterholm, 2008, 2015), different time limits for re-establishing measures were mentioned. In the survey, guidelines mentioned time limits of approximately three months and six months (Oterholm, 2008).

The interview study also pointed to different time limits for young people to access support if they had initially turned it down. One social worker, Frida, said, “We usually say it is six months” (Oterholm, 2015, p. 269), while others said the time limit was one year, and some said there was no time limit.

In the aftercare study (Paulsen et al., 2020), some mentioned deadlines of one year, some provided support to young people without a formal decision, and some left the case open for up to six months before formally closing it to allow for further support.

End of reimbursement from the state

Municipalities receive different levels of financial support from the state based on the age of the children in care. The state (Office for Children, Youth and Family Affairs, BUFETAT) reimburses municipalities a percentage of the cost until the youth turns 20, at which point the reimbursement is terminated. The state also runs institutions and specialized foster homes, which also have an age limit of 20 years (Child Welfare Act, § 9-4).

Seven per cent of the child welfare services that responded to the survey (Oterholm, 2008) gave termination of state reimbursement as a reason for not providing aftercare support. In both the survey and the interview study (Oterholm, 2008, 2015), social workers commented that youths were discharged as early as age 18, despite opposition for child welfare services and the youths themselves. Moreover, these decisions were described as difficult negotiations between state and local services.

In the aftercare study (Paulsen et al., 2020), social workers reported that most support ends almost automatically once a young person turns 20. They mentioned several reasons for this practice, including prioritization of other groups and ambiguity regarding the responsibility to support youths after age 20. In some situations, social workers said it was unclear who should pay for needed residential care, child or adult services; the municipality that placed the child; or the municipality in which the residential care facility was located. Adult welfare services are the responsibility of the municipality of residence; however, child welfare services are the responsibility of the municipality that placed the child. One social worker phrased it in this way:

“We rarely provide aftercare after young people turn 20, almost never up to 23 years. It has to do with finances. After young people have reached the age of 20, they are mainly transferred to the adult services if they need more help and follow-up” (Paulsen et al., 2020, p. 80).

Paulsen et al. (2020) noted the differences in considerations once a young person turns 20. To receive aftercare support from child welfare services, youths older than 20 must not only need aftercare, but also have special needs; however, this distinction is not made in the Child Welfare Act or in any guidelines. Therefore, how funding is organized may create barriers to support for youths. Of course, how long young people should get support from child welfare services can be debated; nevertheless, social workers point to a need for further support that is thwarted because of organizational barriers. While there are different reasons for these organizational barriers, they tend to frame young people based on age limits that do not necessarily relate to their needs. The older the young people are, the less they are framed as the responsibility of the child welfare service. The same exclusion applies to those who have ended support. They are defined as outside and are not evaluated based on their needs, or their “precariousness,” to use Butler’s notion. Thus, these young people are framed differently from other young people: Those who have not received child welfare assistance usually receive support from their families, even if they have moved or are above age 20 (e.g. Hellevik, 2005; Manzoni, 2018; Swartz & O´Brien, 2009).

Organizational barriers can also be found in other countries. In England, for example, youths in foster homes can stay there until age 21; however, this is not the case for young people in residential care (Boddy, Lausten, et al., 2019). In the United States, how long one can remain in care beyond age 18 depends on the state in which one resides, as each has its own policies (Courtney, 2019).

5.4 Possibility to transfer to adult services

In Norway, support for youths between 18 and 23 years (25 years from 2021) with a child welfare background can be provided by child welfare services and/or adult social services; however, an individual’s transference to adult services could serve as a barrier to aftercare support from child welfare services. These two agencies are separate bodies with different target groups situated within different institutional frameworks that influence the support they provide. Adults social services (the Norwegian Labour and Welfare Administration (NAV)) administers financial assistance benefits, employment schemes, activation programs, and various other welfare benefits. Adult social services may supplement or replace aftercare support from child welfare services. Although both agencies offer financial support, advice, and guidance, they differ in their organizations and their interactions with young people, including variations in caseloads, mandates, and institutional logic (Oterholm, 2015; Oterholm & Paulsen, 2018). For example, the institutional logic in child welfare services is described more in line with a caring, parental mindset; in adult social services, the emphasis is on self-reliance, which positions services as a safety net for those lacking other options.

In the survey, Oterholm (2008) reported that 75% of respondents said young people were not given aftercare support from child welfare services because they believed other services could provide more relevant follow-up. In addition, 36% said that if a young person had special needs requiring long-term assistance, they should be transferred to adult services.

In the interview study (Oterholm, 2015), social workers said they tried to avoid getting adult social services involved, but contacted the agency if they thought the young person needed long-term assistance, for example, related to substance abuse or special needs. In these situations, social workers reported that youths were transferred as early as possible.

In the aftercare study, Paulsen et al. (2020) found that child welfare services often sought to transfer financial responsibility to adult social services when young people turned 18, or completed upper secondary school. Workers cited two primary reasons to seek a transfer: (1) they believed it was not the child welfare service’s responsibility to provide financial assistance for living costs, and (2) they preferred that young people in the child welfare service use universal services whenever possible. At the same time, some employees were ambivalent about transferring young people to adult social services, fearing it would increase the risk that the individual would remain in the welfare system. Still, young people needing long-term support were transferred to adult services. Aftercare support from child welfare services was primarily reserved for those who could be expected to be self-sufficient after measures were completed (Paulsen et al., 2020).

Similarly, the nationwide audit (Statens Helsetilsyn, 2020) indicated that child welfare services referred young people to other services when they needed long-term and complex assistance. But child welfare services also emphasized the avoidance of having a young person seek help from adult social services, a practice the board found could put young people at risk of not receiving coordinated help as needed.

The possibility of transferring to adult social services can be a barrier to some young persons’ receiving aftercare support from child welfare services, especially those with special needs or substance abuse. Thus, the most vulnerable youths are framed as outside the responsibility of child welfare services when they reach the age of majority. In turn, they become subject to the dominant logic in adult social services, instead of the more parental-minded logic in the child welfare system. On the other hand, a skeptical attitude toward adult social services may hinder young people from receiving coordinated help from both services. To again use Butler's (2004, 2010) understanding, the significance of how people are framed and thus categorized becomes evident. Young people with special needs are categorized connected to their challenges related to health problems, substance abuse and so on rather than their background as children being exposed to neglect or abuse in need of support from child welfare services.

6 Discussion

The studies examined in this article point to similar barriers to aftercare support for young people in Norway, which are related to prioritization in child welfare services, consent to and conditions for support, organizational barriers, and the possibility of transfer to adult services.

Butler’s conceptualization of how human lives are framed differently provides a lens through which to view these barriers (Butler, 2004, 2010). The ways in which child welfare services relate to youths during the transition to adulthood may imply a change in how society counts these young person’s lives. Based on Butler’s concept, young people are transformed from grievable children into less grievable youths and adults; in turn, as young people are framed as adults, they are situated on the outskirts of the child welfare service’s responsibility. As children are prioritized over youths in child welfare services, young people who are no longer counted as children can therefore be given less support.

Young people themselves may not want to be considered as children, and indeed youths do become adults. However, in the child welfare system, chronological age is definite: at age 18 the individual is no longer a child. This abrupt redefinition is quite different from how young people typically are understood within their families: Even those who move out of their households are still considered children within the family, and often receive continued support from their parents (e.g. Hellevik, 2005; Manzoni, 2018; Swartz & O´Brien, 2009). Within the child welfare “family,” however, 18-year-olds are considered more like adults - adults who must meet certain conditions to receive support - and they seem to be framed to a lesser extent within their difficult backgrounds. Suddenly, their life situations are somehow less precarious, less in need of support. This shift in framing may lead to a failure to relate fully to young people’s life situations, which begs the question as to why concepts like requirements and conditions are used, rather than expectations and dreams about the future. Paradoxically, those who need long-term support are also relegated to the outskirts of child welfare’s responsibility, which presents additional barriers to support.

My argument is not that child welfare should support all young people for as long as possible, or that adult social services cannot provide important support for some; however, these findings point to the importance of how youths are framed and the consequences of this framing for their receiving necessary support. These findings also highlight the ways in which categorization of young people can present barriers to their receiving aftercare. In turn, these barriers may signal a crisis in aftercare in Norway, in which young people are not receiving the support they need - and to which they are entitled.

References:

Backe-Hansen, E., Madsen, C., Kristofersen, L. B., & Sverdrup, S. (2014). Overganger til voksenlivet for unge voksne med barnevernserfaring. In E. Backe-Hansen, C. Madsen, L. B. Kristofersen, & B. Hvinden (Eds.), Barnevern i Norge 1990-2010 En longitudinell studie. Oslo: NOVA, Norsk institutt for forskning om oppvekst, velferd og aldring.

Barne- likestillings- og inkluderingsdepartementet. (2011). Rundskriv om tiltak etter barnevernloven for ungdom over 18 år. Oslo: Departementet.

Barne- og likestillingsdepartementet. (2008). Høringsnotat – forslag til endringer i lov 17. juli 1992 nr. 100 Lov om barneverntjenester (barnevernloven) 23.10.2008. Oslo: Departementet.

Barne- og likestillingsdepartementet. (2019). Høringsnotat - forslag til ny barnevernslov. Oslo: Departementet.

Barter, C., & Renold, E. (1999). The Use of Vignettes in Qualitative Research. Social Research Update (25), 1-1.

Berlin, M., Vinnerljung, B., & Hjern, A. (2011). School performance in primary school and psychosocial problems in young adulthood among care leavers from long term foster care. Children & Youth Services Review, 33(12), 2489-2497. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2011.08.024

Boddy, J., Bakketeig, E., & Østergaard, J. (2019). Navigating precaroius times? The Experiene of young adults who have been in care in Norway, Denmark and England. Journal of Youth Studies, 23(3), 291-306. doi:10.1080/13676261.2019.1599102

Boddy, J., Lausten, M., Backe-Hansen, E., & Gundersen, T. (2019). Understanding the lives of care-experienced young people in Denmark, England and Norway A cross-national documentary review. Copenhagen: FIVE

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77-101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Brännström, L., Forsman, H., Vinnerljung, B., & Almquist, Y. B. (2017). The truly disadvantaged? Midlife outcome dynamics of individuals with experiences of out-of-home care. Child Abuse & Neglect, 67, 408-418. doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2016.11.009

Butler, J. (2004). Precarious Life. The Powers of Mourning and Violence. London: Verso.

Butler, J. (2010). Frames of War When Is Life Grieavable? London: Verso.

Child Welfare Act. 1992, July 17.

Clausen, S.-E. (2008). Ettervern og barnevernstatistikk. In E. Bakketeig & E. Backe-Hansen (Eds.), Forskningskunnskap om ettervern. Oslo: NOVA, Norsk institutt for forskning om oppvekst, velferd og aldring.

Courtney, M. (2019). The benefits of extending state care to young adults. Evidence from the united states of America. In M.-F. o. Goyette. (Eds.), Leaving care and the transition to adulthood. International contributions to theory, research and practice. New York: Oxford Unviersity Press.

Courtney, M., Dworsky, A., Brown, A., Cary, C., Love, K., & Vorhies, V. (2011). Midwest evaluation of the adult functioning of former foster youth: Outcomes at age 26. Chicago: University of Chicago, Chapin Hall.

Courtney, M., Okpych, N. J., Mikell, D., Stevenson, B., Park, K., Harty, J., & Kindle, B. (2016). CalYOUTH survey of young adult´s child welfare workers. Chicago: University of Chicago, Chapin Hall.

Courtney, M., Okpych, N. J., & Park, S. (2018). Report from CalYOUTH: Findings on the Relationship between Extended Foster Care and Youth’s Outcomes at Age 21. Chicago: University of Chicago, Chapin Hall.

Everson-Hock, E. S., Jones, R., Guillaume, L., Clapton, J., Duenas, A., Goyder, E., & Swann, C. (2011). Supporting the transition of looked-after young people to independent living: a systematic review of interventions and adult outcomes. Child: Care, Health & Development, 37(6), 767-779. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2214.2011.01287.x

Gypen, L., Vanderfaeillie, J., De Maeyer, S., Belenger, L., & Van Holen, F. (2017). Outcomes of children who grew up in foster care: Systematic-review. Children and Youth Services Review, 76, 74-83. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.02.035

Hellevik, T. (2005). På egne ben: unges etableringsfase i Norge. Oslo: Norsk institutt for forskning om oppvekst, velferd og aldring.

Herz, M. (2016). Levande socialt arbete, vardagsliv, sörjbarhet och sociala orättvisor. Stockholm: Liber.

Höjer, I., & Sjöblom, Y. (2011). Procedures when young people leave care — Views of 111 Swedish social services managers. Children & Youth Services Review, 33(12), 2452-2460. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2011.08.023

Iversen, A. C., Havik, T., Jakobsen, R., & Stormark, K. M. (2008). Psykiske vansker hos hjemmeboende barn med tiltak fra barnevernet. Norges barnevern, 85(1), 3-9.

Kvale, S., & Brinkmann, S. (2009). Det kvalitative forskningsintervju. Oslo: Gyldendal akademisk.

Lehmann, S., Havik, O. E., Havik, T., & Heiervang, E. R. (2013). Mental disorders in foster children: a study of prevalence, comorbidity and risk factors. Child & Adolescent Psychiatriy & Mental Health. DOI: 10.1186/1753-2000-7-39

Manzoni, A. (2018). Parental Support and Youth Occupational Attainment: Help or Hindrance? Journal of Youth & Adolescence, 47(8), 1580-1594. doi:10.1007/s10964-018-0856-z

Mason, J. (2002). Qualitative researching. London: Sage.

Monrad, M., & Ejrnæs, M. (2012). Undersøgelsesresultaternes troværdighed. In M. Ejrnæs & M. Monrad (Eds.), Vignetmetoden: sociologisk metode og redskab til faglig udvikling. København: Akademisk Forlag.

Munro, E. R., Clare, L., Service, N. C. A., Maskell-Graham, D., Ward, H., & Holmes, L. (2012). Evaluation of staying put: 18 plus family placement programme: Final report. Loughborough: Loughborough University https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/183518/DFE-RR191.pdf.

Olsen, R. F., Egelund, T., & Lausten, M. (2011). Tidligere anbragte som unge voksne. København: SFI, Det nationale forskningscenter for velfærd.

Ot.prp. nr. 61 (1997-1998). Om lov om endringer i lov 17. juli 1992 nr. 100 om barneverntjenester og lov 13. desember 1991 nr. 81 om sosiale tjenester. Oslo: Barne- og familiedepartementet.

Oterholm, I. (2008). Barneverntjenestens arbeid med ettervern. In E. Bakketeig & E. Backe-Hansen (Eds.), Forskningskunnskap om ettervern. Oslo: NOVA, Norsk institutt for forskning om oppvekst, velferd og aldring.

Oterholm, I. (2009). How do the child welfare services in Norway work with young people leaving care? Vulnerable Children and Youth Studies, 4(2), 169-175. DOI: 10.1080/17450120902927636

Oterholm, I. (2015). Organisasjonens betydning for sosialarbeiders vurderinger. (ph.d. dissertation), Høgskolen i Oslo og Akershus, Oslo.

Oterholm, I., & Paulsen, V. (2018). Young people and social workers’ experience of differences between child welfare services and social services. Nordic Social Work Research, 1-11. doi:10.1080/2156857X.2018.1450283

Paulsen, V., Wendelborg, C., Riise, A., Berg, B., Tøssebro, J., & Caspersen, J. (2020). Ettervern – en god overgang til voksenlivet? Helhetlig oppfølging av ungdom med barnevernerfaring. Trondheim: NTNU Samfunnsforskning

Statens Helsetilsyn. (2020). Oppsummering av landsomfattende tilsyn 2019 med ettervern og samarbeid mellom barnevernet og Nav RAPPORT 2/2020 APRIL 2020 «En dag – så står du der helt aleine». Oslo: Helsetilsynet

Stein, M. (2012). Young people leaving care: supporting pathways to adulthood. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Stålsett, S. (2012). Asylbarn og menneskeverd: Etiske refleksjoner med utgangspunkt i erfaringer fra Helsesenteret for papirløse migranter. Etikk i praksis Nordic Journal of Applied Ethics, 6(2), 23-37.

Swartz, T. T., & O´Brien, K. B. (2009). Intergeneratial support during the transition to adulthood. In A. Furlong (Ed.), Handbook of youth and young adulthood. New perspectives and agendas. London: Routledge.

Valset, K. (2014). Ungdom utsatt for omsorgssvikt - hvordan presterer de på skolen? In E. Backe-Hansen, C. Madsen, L. B. Kristofersen, & B. Hvinden (Eds.), Barnevern i Norge 1990-2010. En longitudinell studie. Oslo: NOVA, Norsk institutt for forskning om oppvekst, velferdg og aldring.

Author´s

Address:

Inger Oterholm, Professor

VID Specializied University

+47 222451966

inger.oterholm@vid.no