Knowledge-Production Processes in Practice Research - Outcomes and Critical Elements

1 Multi-sited theoretical and methodological practice

Practice as a concept aroused interest within sociology, philosophy, organisational studies, technology development and behavioural sciences at the end of the 1990s. Some refer to the practice turn in the social sciences (Schatzki & Knorr-Cetina & Savigny 2001). Miettinen, Samra-Fredericks and Yanow (2009), however, write about a return to practice, and draw attention to the fact that there are different generations of practice theorising, ranging from the Hegelian tradition and Marx’s ‘Thesis on Feuerbach’ through pragmatist theories of practice advocated by Pierce and Dewey and concepts of practice in existentialism and analytical philosophy, to more recent theories in the behavioural and social sciences such as those of Pierre Bourdieu, Anthony Giddens, Hans Joas and Yrjö Engeström. The special issue of Organization Studies in 2009 elucidates the manifold nature of both the theoretical and methodological challenges of ‘practice’, at the same time as emphasising the importance of more recent theories.

Practices could be broadly conceptualised as networks that include human actors (such as social workers, nurses, doctors and family members), their activities and interactions, and any kind of resources (such as theories, tools, models, technical artefacts, norms, goals, rules and money) these actors mobilise and utilise in their activities. They encompass different levels, from the micro (what people say and do) to the meso (routines, models) and the macro (institutions), although in many respects these levels do not exist in reality but help us on the analytical level to distinguish between different domains. Still, Miettinen (2009) justifiably suggests that the practice concept calls for the development of vocabularies and approaches that allow transcendence of the division between such levels. We need to understand practice simultaneously, both locally and globally, as unique and culturally shared, present as well as historically constituted and path-dependent.

The theory of practice has frequently been narrowed down to Pragmatism at the same time as interest in Pragmatist thinking has significantly increased. This is evident in the recent re-publications of Dewey’s work (2006) and anthologies of Pragmatism in both philosophy and social science (2008). Although this perspective is crucial, is the practice turn a question of returning to practice theories of the first generations such as Dewey and Pierce, or a question of creating a new theoretical and methodological eclecticism? Does complex and multidimensional practice necessitate eclecticism? Moreover, what can we gain by turning to the first generations? An interesting piece of work that has perhaps not been recognised in this realm is Anselm Strauss’ ‘Continual Permutation of Action’ written in 1993. Here Strauss scrutinises his previous writings in order to develop his interactionist theory of action, urged on by the social scientists Fritz Shütze and Hans-Georg Soeffner, who were afraid that the embodied Pragmatist thinking on action and social reality would not be unravelled. What does Strauss do? He interprets the Pragmatist tradition through his work and sets out a list of 19 assumptions or hypotheses concerning how to study practice. It is a wonderful synthesis that elucidates ontological, epistemological and conclusive elements, ranging from the notion that the body is a necessary condition for action to the relevance of tracking down conditional paths in actions, the usefulness of distinguishing between the routine and the problematic, and the fact that interactions bring about identity change. What triggered Strauss was the fact that all researchers and social scientists make assumptions about action and interaction, and these assumptions greatly affect their conclusions, interpretations and procedures. He therefore urges explicitness and sensitivity towards sociological phenomena, and hopes that the list will challenge other readers/scientists to explicate their own assumptions on action and practice.

Practice is not just about theory, however, it is also about methods. It has been claimed that practice research does not require a particular methodology or strategy (McCrystal 2000), and that the very concept is an assemblage comprising a variety of processes and methodologies (cf. Styhre 2003). Methodologically speaking, practice has traditionally been at the core of ethnography, ethnomethodology and anthropology. Empirical methods emphasising the reflexivity of Pragmatism have prevailed mainly in pedagogy (Mezirow 1991) and organisational research (Schön 1983). In the social sciences, action research and participatory perspectives with their roots in the Chicago school have maintained their place at the margin of social research for decades (cf. Saurama & Julkunen 2009). Nevertheless, there is now interest in developing an integrated concept that will bring together different methodologies and processes focusing on practice. This will mean looking more closely into the elements of knowledge production, and in particular acknowledging the different purposes of knowledge.

If we take Pragmatism as our starting point we understand that knowledge is clearly related to action (Dewey 1931). It is therefore worth clarifying how we look at action in the knowledge-production process. In what way is it a purpose and an object? A Swedish researcher in information systems (IS), Göran Goldkuhl (2008), distinguished three functional divisions in IS from a socio-pragmatic perspective. 1) Referential pragmatism describes the world, the activities and actions as well as the actors in it, and the conditions for and results of the actions; it is provisional knowledge, knowledge about action, which is the object. 2) Functional pragmatism views knowledge as a way of improving practice: practice is still in a state of becoming and knowledge should be useful. Knowledge is prescriptive in character. It is knowledge for action, the action being the purpose. 3) Methodological pragmatism is based on the fact that we learn about practice through action, and that the true nature of the phenomenon is revealed when we try to change it. It is prospective knowledge achieved through action, as action is the source and the medium.

This article is based on the processes of research conducted in the institutes of practice research in Helsinki, Finland. Through the prism of Pragmatist thinking and socio-pragmatic knowledge classification I will tentatively examine how these ideas have been translated into a working model, and further on analyse what kind of research models work in practice. I will start by determining what is at the core in the knowledge-production process, and then go on to investigate the infrastructure and the different practice-research processes.

2 Co-productive knowledge – the core of the practice-research process

The aim in practice research is to create a reflective relationship between practices in different contexts and the prevailing conceptions and theories in the social sciences. The research process is attached to the practice and its development, and is focused on increasing the visibility of social work, not only in terms of describing the practice but also attempting to continuously re-evaluate the conceptions (Saurama & Julkunen 2009). As Shaw (2007) states, the research process is characterised by its orientation to change, that is to say that the function of research is to find different ways and solutions for developing practices. One of its objectives in particular is to bring out the experiences and knowledge of the users (Satka et al. 2005).

Two concepts, developed by John Dewey and Georg Herbert Mead, are of significance in understanding the emergent, becoming nature of practice: transactionality and corporeality. They emphasise the notion that entities, including humans, change and gain meaning through interacting. The interaction enhances the process of co-becoming and converges the methodological ambitions of process-oriented approaches to the social sciences (Miettinen et al 2009).

It seems to be characteristic of practice-based knowledge that it is personally experienced. Strauss (1993, cf. Mead) argues that the corporeality of knowledge means that no action is possible without a body, that there is no divide between the external and interior worlds, and that self-consciousness is a cornerstone in professional practice. This concerns all the actors - researchers, practitioners and users - who enter into action. By continuously reconstructing the conceptions we understand the present and project forward into the future in order to be able to act. Thought processes make reconceptualisation possible and routines can be a possibility, as routines are a central feature in Dewey´s action scheme (1922): when it breaks down reflection is called into play in order to get the action going again.

Conceptualisation requires much expertise from the researcher: it calls for methods of thinking learned in scientific research, systematisation and research logic, approved methodological practice and good background knowledge of the relevant literature. Most of all, however, it requires a research and learning community and testing of knowledge formation in practice. Not surprisingly, Hakkarainen, Lonka and Lipponen (1999) point out that meta-conceptual awareness comes only through active involvement in the research process. This points to Bourdieu's Theory of Practice, which so eloquently describes the different standpoints we should take:

To do this, one has to situate oneself within real activity as such, that is in the practical relation to the world, the preoccupied, active presence in the world through which the world imposes its presence, with its urgencies, its things to be done and said, things made to be said, which directly govern words and deeds without ever unfolding as a spectacle. It is possible to step down from the sovereign viewpoint from which objectivist idealism orders the world, but without having to abandon to it the ”active aspect” of apprehension of the world by reducing knowledge to a mere recording. (Bourdieu 1990, 52)

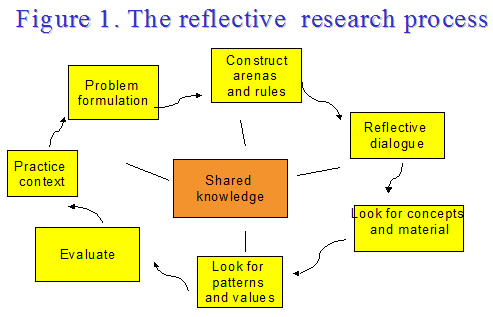

The Finnish education system for social work offers students courses in both research and practice-research methodology. The latter involves both theoretical studies and a two-month practice-research internship in a welfare setting. Furthermore, the education system offers doctoral studies and a research community for students focussing on practice research. Practice research may be ideally pictured as an iterative process of reflection, critical examination and collective engagement. This is outlined in Figure 1 below:

Peer learning is built on mutual support, in other words on being supported and giving support. It is an emotional, social and dynamic process. Through learning communities individuals become aware of their own mental commitments and gradually start to change them. Learning always involves emotions, without which it is claimed not to be possible. Emotions and factual knowledge are intertwined, and entail learning by doing and actively testing skills. This comes close to forms of auto-ethnographic work embracing personal thoughts, feelings, stories and observations as a way of understanding the social context we are studying (White & Riemann 2009).

A supportive environment cannot be mandated, but it is possible to create the conditions in which it can be fostered (Hakkarainen & Lonka 2001). Susanne Hyväri (2005) concludes that for peer learning to be successful a common space is needed in which experiences can be shared. Specific elements are the building blocks in peer learning. In our setting we build on theories of knowledge management and learning communities (Wenger 1998, Hakkarainen 2003, Nowotny 2003). Hakkarainen and Lonka (2001), for instance, refers to research-oriented learning, of which the common denominator is shared knowledge. We have also found support in first-generation pragmatists such as Dewey with his action scheme and Mead with his practice models.

A learning community requires also a set of shared rules. Habermas’ theory of communicative action (1987) rules out authority-based institutions based on anything other than a good argument, and offers perspectives on how critique and change could be extended to the reach of actors. Habermas stresses that certain requirements need to be developed for building a responsive culture: a) that the speech act is true in relation to the normative context, b) that a true speech act is performed so that the listener may share the knowledge of the speaker, and c) that opinions and feelings are uttered so that the listener can believe in what the speaker says. Shotter and Gustavsen (1999) developed this theory further and transformed dialogical criteria into an operational form according to which free communication without domination is possible. They formed a criterion known as the method of discussion and democratic dialogue. Their point of departure was that real operational changes required the involvement and participation of several different parties. Habermas’s objective could be interpreted as to build a bridge between the culture of experts and everyday life, and therefore enrich and challenge different perspectives that might have been taken for granted. Democratic dialogue could thus be seen as a tool that enhances practitioners’ self-understanding of their practice. Social-work-practice research knowledge is tied to the need to develop practice. It promotes interaction and equal discussion among different actors in order to enable change.

Learning is often about solving problems and understanding conflicts. Practice requires forms of understanding that are in themselves practical and can be shared. This is manifested in the peer-working process. Problems, successes and stories are brought into the group and provide material for learning. It is the practitioners and the students who set the agenda, with their questions, uncertainties and descriptions of how the different steps have been taken. It is joint action within which the dialogue between the theoretical and the more practical is conducted (cf. Shotter 1999).

Karvinen-Niinikoski (2005) posits that the shift towards open expertise has increased the significance of interaction. Expertise is not a question of individual professionals storing information and knowledge within themselves, but rather entails the communication and construction of knowledge, and the development of creative models based on a sense of community. The role of the researcher has to be expanded from that of a self-appointed expert to one of a reflexive and dialogical interpreter. Rather than providing a portrait of the Other (person, group, culture), the researcher is also obliged to construct a portrait of the Self (Hammersley 1992, Mead 1932). In generating a co-operative practice researchers attempt to realise the ideal of reflexivity and embrace personal thoughts, stories and observations as a way of understanding the context. This is in contrast to hypothesis-driven, (post)positivist research. Here again we could find support in the first generations of practice research through Georg Herbert Mead (1932) and Dewey (1949) in that both past and future are present in current situations and actions, and actors continually reconstruct their history in order to understand the present. Clearly, recent theories build on these foundations, one of which is Emirbayer & Mische’s theory of human agency (1998). The theory posits that the agentic dimension of social action can only be captured within the flow of time. This means reconceptualising agency as a temporally embedded process of social engagement, informed by the past but also oriented towards the future and the present. All this entails the three constitutive elements of agency, iteration (past patterns), projectivity (future trends) and practical evaluation (the present). Emirbayer and Mische draw on Mead (1932), who insists that self-reflective activity that engages with the meaningful structure of the past essentially refers to the future. This conceptualisation may well encompass an extended dialogue between ideas and evidence that explores the beliefs and actions associated with life under differing structural and cultural conditions.

The aim in practice research is to find forms of knowledge processing that aim beyond provisional knowledge. For knowledge to be actionable it has to be embedded in professional practice on the one hand, and to take a critical stance on the other. Applying the criterion of democratic dialogue may bring critical and expansive learning to the whole process of knowledge formation. The point of departure is that real operational change requires the involvement and participation of several different stakeholders and actors. Democratic dialogue could also be seen as a tool that enhances self-understanding regarding practice. The knowledge interest in social-work-practice research lies in practices and their development. The emphasis is on interaction and a balanced discussion between different parties in order to enable change. Learning in a community of practice involves learning by doing, generating meanings, the formation of identity and participation in the community (Wenger 1998). Thus, learning in a community may bring about change in professional practice, but the prerequisites include strong embeddedness in practice involving actions, reflections and further scrutiny, and a theoretical basis to ensure that the research also has a general perspective.

3 Introducing the infrastructure of the practice-research context

The context of practice research in this article is an institute founded for that purpose. There are two such institutes for social work in Helsinki, Finland, the Heikki Waris Institute and the Mathilda Wrede Institute. My focus here is on the activities of the latter, particularly on the practice-research models in use within the institute. I scrutinise certain examples of practice research, specifically the relationship between knowledge, action and change.

The Mathilda Wrede Institute (MWI) is a practice-research unit at the intersection of education, research and practice, the aim of which is knowledge development in social work. It operates in cooperation with the Centre of Expertise within the municipal social services, and the professional practice encompasses elderly care, financial aid and social assistance, family services, and child-protection and handicap services. The institute was founded in 2002 and operates on the basis of a written contract between the local municipalities, the university, various polytechnics and the regional Centre of Expertise within Welfare Services. Thus, there are close relationships with both the scientific community, the practice and the broader networks of the centre of expertise. Altogether these form a dynamic learning society.

The University of Helsinki funds the practice-research professorship and lectureships, and the Social Services Department has established researcher/social-worker posts at the institute. The idea is that social workers coming from a specific field of study engage in two-year projects. The subjects of research are agreed upon in the boards of the institutes comprising the different parties involved.

The three main study lines within the institute are as follows:

1) Knowledge-development processes on the borderlines between education, research and practice.

This includes developing networks and structures involving practitioners, users, students, researchers and managers. Multi-professional practice units that combine teaching (courses incorporating practice and internships), learning and research are now being piloted in real-life welfare settings within and outside the capital area. Educational modules are developed and tested, such as Biographical Work modules and Youth and Social Change modules, and open seminars and research cafés are organised. All these activities are documented and serve as research material. The key issue is the connectedness to the education in social work. The close connection with the centre of expertise also allows for the development of further-education courses.

2) Methodological developments in practice research

Here-and-now practices impose particular requirements on empirical research and data collection.

Trans-disciplinary methodological workshops are held involving researchers and students as well as practitioners, in which various research processes are scrutinised. Practice-research processes are supervised reflectively in groups. It is a question of joint work on research material such as transcriptions and field notes, as well as reflection on the writing process. This is a time-consuming and long process that is embedded and implicit in all the different practice-research endeavours within the institute. Hence, the methodological developments are not an aim as such but are latent in all the research processes.

3) Practice research on current issues and topics

Practice-research studies are mainly researcher/social-worker based, but also involve project researchers and developers, as well as Master’s-level students. The studies encompass themes as variable as ‘The limits and potential of social work in disability services’ (Sjöblom 2008), ‘World views and life-historic perspectives in multicultural social work’ (Lindroos 2008, cf. Parkkinen & Puukari 2005), ‘Participatory research with disabled persons’ (Lindqvist 2008), ‘Reflective knowledge development on early intervention in substance abuse’ (Fagerström 2010), ‘Encountering boys’ perspectives in school and welfare work’ (Lunabba 2010), ‘Social-worker agency in rehabilitation with the elderly’ (Krokfors 2009), ‘Adoption counselling processes – from a professional and a user perspective’ (Eriksson 2007, 2009), ‘IT and changes in child-protection processes’ (Koskinen 2010) and ‘Facilitative mediation in solving family conflicts’ (Bergman-Pyykkönen, Haavisto, Karvinen-Niinikoski, Mattila-Aalto 2010). All these involve group-based supervision, as well as peer groups. The research processes also encompass reference groups involving experts and users.

A cornerstone of practice research is the development of research capabilities among social workers. This is incorporated into the Finnish Master’s educational programme for social workers, which offers not only the opportunity to work with welfare-service users, but also the resources to carry out research. This reflects a long tradition in social work. In the 1920s Edith Abbott and Sophonisba Breckinridge emphasise the capabilities of social workers in the work of the Hull House settlement in Chicago, defending the view that social workers possess significant scientific abilities and that research should not be the exclusive domain of social scientists (Shaw & Bryderup 2008, cf Saurama & Julkunen 2009).

There has been a considerable increase of interest among students of social work in studying professional practice. Students often work while they are studying, and research questions arise from practice. They are encouraged to undertake empirical studies on research problems that have emerged in their professional practice. The existence of practice units, including learning communities , practice-research courses and group tutoring, has certainly paved the way for this form of empirical study. In addition, the new strands of social-work research reflect the fact that it has become a legitimate domain for practitioners (White & Riemann 2009). It is not always just answers the practitioner/student is looking for, however. Social workers often bring a different perspective to research: they are not necessarily content with repeating known facts, and are interested in liberty and change. The following example illustrates this:

My research question arose from my professional practice. Every once in a while I found myself in situations when I realised that the knowledge I had about unemployed people in general, that is the knowledge I had gathered from research, my studies and the media and built up during my life did not add up or suffice. My clients told me something else, surprisingly, and I wondered what made them act and choose the path they did. Likewise I realised that the training that I was responsible for did not work as well as I wanted it to. I wanted change and development, and I wanted to have my clients involved in this project. Besides, the fact that we developed the content of the training together also brought the life stories in focus in this development and research project. I wondered how I could use the life stories in these employment-training courses. What new perspectives would they bring to the individual’s career and to the training courses as such? (Bergman-Pyykkönen 2009, 5)

4 Practice-research (PR) processes

In simple terms, the aims of practice research could be summarised as to create scientific knowledge that has practical value, and to generate practical knowledge through empirical studies on a local level (Goldkuhl 2007). The local level is a controversial issue in scientific discussion, however. Is the relevance only to be seen on the local level? According to Shaw (2007), for instance, the research process is characterised by an orientation to change, and its function is to find different ways of developing practices. Still, we need to look at different levels and scopes of change. Reason and Torbert (2001) differentiate the scope in terms of first-person, second-person and third-person inquiry. First-person inquiry refers to the reflective researcher who brings inquiry into everyday practice, seeing research as informing the practice and him or herself perhaps as a self-appointed change agent. Second-person inquiry is more co-operative, involving a group of co-researchers engaging together face-to-face in cycles of action and reflection through research. Finally, third-person inquiry goes further than this, the aim being to make a broader contribution through engaging larger systems in a democratic process. By engaging people in broader debates a more external validity may be insured. These distinctions raise the questions of whether the aim of practice research is to achieve intended outcomes (single-loop feedback), whether it is congruent and embedded within the strategies of practice (double-loop feedback), and whether the outcomes are congruent with both a local and a general perspective (triple-loop feedback). Goldkuhl (2007, 2008), as mentioned above, distinguishes between referential, functional and methodological pragmatism, arguing for a full pragmatism that combines an interest in describing, explaining and theorising on practice (referential pragmatism), using knowledge as a means of improving practice (functional pragmatism) and active participation in testing and exploring new ways of working (methodological pragmatism). It is a question of carrying out rigorous and worthwhile research, and making sure that the outcomes are relevant in and for practice while at the same time expanding and promoting general knowledge. This stretches the research process from co-production to co-evolution. Helga Nowotny (2006) points out the co-evolutive aspects of science, claiming that validity should be repeatedly tested not only within the practice but also outside the community in different networks. Hence, the main problem is not the locality of knowledge, but how we treat that local knowledge. Do we commit more strongly to the context in a theoretical sense, as Nowotny, Scott and Gibbons (2002) suggest, or do we follow Gredig and Sommerfeld (2008, 164): ‘If we want scientific knowledge and especially empirical knowledge to play an effective role in professional action, then we have to focus on the contexts where the processes of generating knowledge for action actually take shape, that is, on the organizations engaged in social work’. Taking local knowledge as the challenge is the challenge facing practice research.

5 Four models of practice research

Different models of knowledge production prevail in the institute, and researcher/social workers are encouraged to try new methodological applications and new points of departure. Support for this is provided in the form of methodological workshops and collective tutoring, as well as in critical reflection among practitioners and users. The knowledge-production processes are open-ended and path-seeking, although some models with distinguishable core elements have emerged.

This modelling builds on experience from almost a decade of development and application in practice research. The focus has been on the infrastructure, the methodology, and the processes of knowledge production, dissemination and use through the lens of socio-pragmatic knowledge classification and change. I tentatively recognize four different practice-research (PR) processes.

The practitioner-oriented PR model: a development-oriented model in a real welfare-service setting. The workload is shared between practice and research. There are various options, ranging from a weekly division between clinical work and research work to monthly arrangements requiring practitioners to set aside time for research. Social workers may be involved in a development project in which the tacit knowledge and the essential elements inherent in working processes are described and evaluated through analyses of critical incidents, monitoring and interviews, for example. In Goldkuhl’s terms this could be categorised as referential pragmatism, as knowledge about action with a more descriptive purpose in the search for provisional and local knowledge. It could also be a question of identifying good practices and making social work visible, which may be disseminated to other contexts as well. An example of this is Eriksson’s (2007, 2010) examination of adoption counselling processes, in which the aim was to describe, explain and theorise practice. It was based on the practitioner’s/researcher’s own experiences, analyses of critical incidents, and reflective dialogue with other practitioners including external reference groups representing different types of expertise within the field. This gave it wider validity. New conceptualisations may emerge from the study of underlying reasons and resources, and analyses of patterns. The focus of change is rather latent, informing practice but also bringing new insights through reflection throughout the process. Another example was when the social worker took some time to develop the partner work model further within elderly care (Pontán 2008): she engaged the whole team in analysing the critical elements.

The method-oriented PR model: a model involving the development of new methods in partnership with service users and practitioners. Research and practice overlap and proceed simultaneously. The interest is in knowledge for action, action being the object of the knowledge, although this is not action in the ‘here and now’ but action in the future: in emerging practice. It is a dialogical and exploratory process involving users, practitioners and researchers. It is strongly embedded in local practice, but strives to generate more general knowledge. The researcher and the practitioners actively participate in testing and exploring new ways of working (methodological pragmatism). The explorative element places a lot of methodological demands on the knowledge-production process. The model is research-driven, although the researcher slides along the axes of developer and researcher. There is grounded involvement in empirical research, and it is rooted in action research and an ethnographic approach involving the researcher in different levels (Okely 1992). Being grounded in experience-based knowledge creation makes it different from mainstream sociological ethnographic (Lindroos 2008).

This is the most prevalent PR model in the institute and there are many examples of its use. Co-operative inquiry has been used for studying world views in multicultural work, and in early intervention in drug use in families. Knowledge is produced in order to develop practice, and the researcher is both subject and object. This demands self-reflectivity and systematic monitoring of the research process, as well as facilitating critical reflective forums among the practitioners involved. Hence critical hermeneutic reflection is involved. Through building learning spaces the practitioners are able to take a critical stance and find a new perspective on their own existence and the existing institutional phenomena.

Both practitioners and users are considered co-producers of knowledge. How we as practitioners and researchers understand complex and everyday practices is based not only on theories, but also on experiences, descriptions and practical ways of knowing (Fagerström 2010). It entails the use of different techniques such as videos, writing, and subjective and group reflection. Analytically it is a challenge to make sense of multi-actor dialogues, and a special dialogical method is being used.

The democratic PR model: a democratic bottom-up research model involving the continuous involvement of practice reference groups, including users, practitioners and leaders. The aim is to change practice locally at the same time as liberating the actors within the research context. The focus is not directly on work processes, but is more comprehensive. The idea is to seek knowledge through action, and there is a strong local perspective. Action is both the source and the medium. Knowledge is seen as a means of improving practice (functional pragmatism).

The objective in this approach is not only to study the individual level of participation but also to take a societal perspective, and it therefore leans towards participatory research in terms of design. It is oriented towards the details of the settings and actors, their actions and experiences in everyday life, as well as in the intervention the research imposes on the process. It engages larger systems seeking for broader debates and at the same time empowering participants to create their own knowing-in-action in collaboration with other actors.

Anne-Marie Lindqvist’s (2008) study on “Participation in a care and research context” serves as a good example of this model. It examines participation in both contexts of individuals with disabilities. Methodologically the study was phenomenological, the aim being “to grasp the actual issues and adapt the scientific methods according to the studied reality (Jan Bengtsson (2002, 14, Lindqvist 2008). It is a question of making sense of human practices on their own terms in a process in which the users became co-researchers in the study. The research process itself became part of the research material, and the researcher was involved as both the subject and the object. The process was transparent and included regular dialogue between the different practising actors. The research design involved a reference group in which users were involved. This group was active in developing the interview questions and guide, sharing their experiences of participation, contributing to the interpretation of the data material and functioning as a reflective partner during the whole research process. Two of the users were also involved as interviewers (users interviewing users). It is clear that the participation of users brought a critical perspective to the research in that it simultaneously shed light on the plurality and perplexity of the concrete implementation of work in practice.

The generative PR model: a process involving alternative periods of field practice and research – analysing, conceptualising and theorising. The aim is to acquire knowledge through action, and the model could be categorised as functional pragmatism: knowledge is seen as a way of improving practice and action is both the source and the medium. However, knowledge has a prospective character, and the research design has a generative perspective. The aim is not to solely build and produce knowledge for a specific practice but to generate knowledge through different practices. The research methodology is a source as well as a medium, and the methodological perspectives are more explicitly evaluated and developed during the process. This is a mixture of methodological and functional pragmatism.

An example of this approach is an ethnographic study in schools in Helsinki in which the purpose was to develop knowledge on how boys’ needs for support are recognised and met, and how boys make use of school welfare practices (Lunabba 2010). The study also explores boys’ constructions and experiences of welfare practices. The concept of welfare practice is broadly understood as involving both professional practices conducted by welfare professionals and other forms of support provided by other adults in the school (teachers, assistants and other personnel) to boys in their everyday school communities. What is interesting in this ethnographic study is how the researcher/social worker uses his experience in child protection, how he has regular interaction with the child-protection workers, and how he tests the possible conceptual innovations and developes them further within the research. This kind of research process is open-ended and crosses different boundaries.

The methodological standpoint is inspired by John D. Brewer’s (2000) writings on postmodern ethnography, where particularly the role of the researcher is scrutinized. Lunabba (2010: no page number available) describes his own position in a following way:

I never tried to hide my purpose of being in school. I was open about my premises of

being in school as a researcher in social work with an aim to study welfare practices

with boys. In my ambition to approach boys I chose to actively participate as well in the formal activities in classrooms and in informal activities during breakes and school fieldtrips. I found it to be more natural to do what adults usually do in the context of a school than to lurk in a back of the classroom with my laptop or a note book. Some of the teachers offered me small tasks in class, such as dealing out material or helping out with group work. In some classes especially in mathematics and technical handicraft young persons turned to me with their questions concerning schoolwork and I offered my help the best that I could.

I allowed myself to be dragged in to the formal activities as well as be approachable and available for both students and teachers. I have come to define my role in school as being one of the adults in school. To do what adults usually do in school, which is to help out with schoolwork, was a natural way to blur in to the school setting and interact with the students. Approaching boys as one of the adults gave me also first hand experiences of the practical challenges in encountering boys in school. Even though I did not take an already existing position in school pretending to be a teacher or a teacher assistant, I believe that I very much approached boys through same kind of terms as adults generally approach boys in school.

An analogous point of departure in this concrete research project was the well-known Barneby Skå community in which 70-80 troubled young boys between the ages of seven and 15 lived in the 1960 - 70s. Gustav Jonsson and Anna-Lisa Kälvestan, who built the research community on practice and research, wanted to learn more about the kind of phenomena they were working with and the kind of results the community produced. Their point of departure was interesting: the idea was not to produce material about youngsters in the Skå community, but to study boys in general living in Stockholm. In this way they were able to form a theoretical framework that functioned as a mirror for the practice (Börjesson 2004; Vinterhed 1977). By studying the family relations of the children and the communities in an innovative manner the researchers managed to form a significant theoretical basis on which to develop child-protection practices (Jonsson & Kälvestan 1964).

6 Conclusion: Critical elements of the everyday architecture of practice research

Using and promoting different PR models fosters progression in terms of theory, methodology and dissemination. Such models should be seen as dynamic rather than dogmatic, therefore allowing for progression. They build on different methodologies and theories which allows for a critical stance. One may conclude that the multi-dimensionality of welfare practices necessitates theoretical and methodological eclecticism, but the cornerstone is that these are made visible. But can we find common critical elements within these practice research models?

7 Embeddedness

Many writings, particularly in Britain but also in some Nordic discussions, place the focus of practice research particularly on the practitioner. For example, Knud Ramian (2004) suggests that a social worker carrying out research needs to spend 80 per cent of his/her time at work in order to guarantee practice embeddedness and the direct use of knowledge. There is a critical point in this, however: the research may be person-dependent, and given the evident personnel turnover in the welfare sector this is a risk. The crucial element of practice research, then, is practitioner and research embeddedness within the structures and contexts of research rather than in a particular person. In any case embeddedness can be – and has to be – guaranteed on different levels.

8 Learning through reflection and visibility

With its focus on knowledge and aspiration towards participation, collectivity and innovation, practice research can benefit greatly from ideas developed in different fields of study such as ethnography, action research, action theory and developmental work research. The process includes conceptualisation, analysis of patterns and the evaluation of outcomes. Church and Bitel (2002) urge us to move away from simple cause and effect analysis and to build in participative reflective processes if we are to capture the diversity and breadth of our work.

The examples described in this article draw attention to both the role of the researcher and the process of knowledge production and dissemination. The models could be characterised as a continuum moving from the more traditional design with a researcher who brings inquiry into practice and sees the research as informing the practice, to more co-operative inquiry in which groups of researchers and practitioners engage in cycles of action and reflection through research. The validity is tested inside the practice in dialogue with the actors involved. The models follow an open and extensive process involving multi-dimensional networking and encounters at the interface of various operating contexts. Research is an active partner in the process of knowledge acquisition, and validity is tested not only within the practice but also outside the community and in different networks. This could be called the co-evolution of science and society, in the words of Helga Nowotny (2006).

Dialogism and Pluralism as central values

“Practice gives words their sense”, as Wittgenstein (1980) wrote, assuming that all our meaningful social practices originate in and develop as refinements of the spontaneous, responsive reactions occurring between us. As we talk to each other we are constructing the world we see and think about. What other people do to understand practical issues is to form relationships with each other, and this goes beyond simply mutual understanding. Burbules (1993) and Mönkkönen (2007) highlight the concept of dialogue as a process of communication that is directed towards new discovery and new knowledge. Dialogue is not a goal in itself, but a process that supports many other goals. It is both a practice that helps us to achieve phronesis (practical-moral knowledge) and a regulative ideal that points us towards the tasks that we need to undertake. As a practice it is not eristic but constitutes conversational interaction directed towards learning. The aim is not to change people but to effect change in and by participants in the dialogue. Common spaces where experiences can be shared and challenged are thus important, but it is the form of extended dialogue that is crucial. It is the agentic dimension in the present that challenges the future.

Prospectivism and external validity

Dewey (1922) argued that whatever the scale of a piece of research, dissemination of the main results is a key component of the research process. The notion of how change in practice takes place becomes visible through dissemination. Arnkil (2006) compares different concepts of knowledge dissemination and various development strategies, identifying rational planning, the learning organisation and an everyday ‘complex response’ model, all of which have an impact on development efforts and concepts. Knowledge cannot be apprehended solely as a commodity to be transferred from one person to another irrespective of its origin. The starting point is that knowledge is formed through interaction with people when people are able to encounter one another. Nowotny (2003) coined the expression robust knowledge, which captures the social processes of practice research:

-

It is tested for validity both inside and outside the community – internal and external validity

-

It is tested through the process of extension

-

It is repeatedly tested, science as an active partner participating in the process of social knowledge

-

It describes the process not the product.

9 The continuous ethical aspect

There is a need to continuously reflect the ethical aspects in practice research. The ethical aspects should be present from the first phases and contacts with service users and other involved actors. Thomas & O’Kane (2000) argues that the ethical aspects should challenge the researcher’s commitment to collaboration, to a balanced sample, and to client-centeredness in sharing the findings. Sometimes it means, like in Lindroos’ (2008) study that a client case is withdrawn from the study. The most challenging element still being the dissemination phase, how to make use and share new insights.

Through the prism socio-pragmatic knowledge classification I have examined how practice research can be understood and how these ideas of socio-pragmatic knowledge have been translated into a working model, and further on analysed what kind of research models work in practice. Four different practice research models have been identified: 1) The practitioner oriented PR process 2) The method oriented PR process 2) The democratic PR model and 4) The generative PR model. These models should be seen as dynamic rather than static, and allowing for progression. They build on different methodologies and theories. Nonetheless, the multi-dimensionality of welfare practices necessitates theoretical and methodological eclecticism, and the cornerstone of good practice research is that this eclecticism is made visible. Practice research is not simply a question of specific inputs but is a matter of continuous relationships, explicit methodologies and actions on different levels which are supported by an infrastructure: an everyday architecture of research. For practice research to be to be useful it needs to be embedded, reflective, dialogical, pluralistic, rigorous, prospective and ethical.

References

Alasoini, T., Ramstad E, Hanhike T, Rouhiainen, N. 2008: Learning across Boundaries. Workplace Development Strategies of Singapore, Flanders and Ireland in Comparison. Publication of the WORK-IN-NET Project. Helsinki.

Arnkil, R. 2006: Hyvien käytäntöjen levittäminen EU:n kehittämisstrategiana. In Seppänen-Järvelä, R, Karjalainen, V (eds) Kehittämistyön risteyksiä. Helsinki: Stakes.

Bergman-Pyykkönen, M. 2009: ”... för jag berättar ju det här också för mig själv.”

Aktionsforskning om livsberättelser som redskap i arbete med arbetslösa. Avhandling pro

gradu i socialt arbete. Helsingfors universitet. http://www.fskompetenscentret.fi/page105_sv.html (”... because I tell this also to myself,” Lifenarratives as a Method when working with Unemployed People. An Action Research. Master’s thesis in social work. University of Helsinki.)

Bergman-Pyykkönen, M.,Haavisto, V.,Karvinen-Niinikoski, S., &

Mattila-Aalto, M. (2010) Konfliktin hallinta osana vanhemmuutta – fasilitatiivinen

perhesovittelu perheitä tukemassa. Esitys Perhetutkimuksen päivillä 19.2.2010, Jyväskylän

yliopisto. (Conflict Solving as part of Parenthood - Facilitative Family Mediation

supporting Families in Conflict. Conference paper presented at the annual conference for

family research at the University of Jyväskylä 19.2.2010.)

Burbules, N. 1993: Dialogue in Teaching. Theory and Practice. New York: Teachers College Press.

Church, M., Bitel, M., Armstrong, K., Fernando, P., Gould, H. Joss, S., Marwaha-Diedrich, M., de la Torre, A. & Vouhé, C. 2002: Participation, relationships and dynamic change: New thinking on evaluating the work of international networks. London: University College

Dewey, J. 1922: Human Nature and Conduct: An Introduction to Social Psychology. New York: Henry Holt.

Dewey, J. 1929: The Quest for Certainty. A Study of the Relations of Knowledge and Action. London: George Allen & Unwin

Dewey, J. 2006: Julkinen toiminta ja sen ongelmat. Tampere: Vastapaino.

Fagerström, K. 2010: Poster presentation: Eyes Wide Shot – Critical Reflection as a

research method to support early intervention. Joint World Conference on Social Work and

Social Development, Hong Kong

Gibbons, M., Nowotny, H., Scott, P. 1999: Rethinking science: Knowledge and the public in the age of uncertainty. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Goldkuhl, G. 2007: What does it mean to serve the citizens in e-services? International Journal of Public Information Systems, vol 3; 135-159.

Goldkuhl, G. 2008: What kind of pragmatism in information systems research? AIS SIG Prag Inaugural meeting, Dec 14, 2008, Paris.

Hakkarainen, K., Lonka, K. & Lipponen, L. 1999: Tutkiva oppiminen. Älykkään toiminnan rajat ja niiden ylittäminen. (Researching learning: Porvoo: WSOY.

Hammersley, M. 1992: Deconstructing the qualitative-quantitative divide. In Brannen J (ed.) Mixing Methods: qualitative and quantitative research, Aldershot: Avebury.

Joas, H. 1996: The Creativity of Action. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Jonsson, G., Kälvestan, A.-L. 1964: 222 Stockholmspojkar, en socialpsykiatrisk undersökning av pojkar i skolåldern. Stockholm: Stockholm universitet.

Julkunen, I., Korhonen, S. 2008: Effectiveness through dialogue. In Inge B (ed) Evidence Based and Knowledge Based Social Work. Research Methods and Approaches in

Social Work Research. Danish School of Education. Aarhus University.

Kilpinen, E., Kivinen, O., Pihlström, S. 2008: Pragmatismi filosofiassa ja yhteiskuntatatieteissä. (Pragmatism in philosophy and social science) Gaudeamus: Helsinki.

Koskinen, R. 2010: Lastensuojelun sosiaalityö ja asiakastietojärjestelmä muutoksessa (Social work in child protection and information technology in change). Manuscript.

Lindroos, M. 2008: Att utforska världsbilder i samtal - en praktisk forskning i mångkulturellt socialt arbete. (To study worldviews in dialogues – a practice research within multicultural social work). Helsinki: FSKC Rapporter 1/2008.

Lindqvist, A.-M. 2008: Delaktighet för personer med utvecklingsstörning i en forsknings- och omsorgskontext. Helsinki: FSKC Rapporter 5/2008.

Lunabba, H. 2010: Applying ethnographic methodology in encountering boys in upper-level comprehensive school contexts. Paper presented at Ethnographic Workshop - Methodological challenges in Ethnographic studies,17.5.2010 University of Helsinki.

Mead G. 1932: Philosophy of the Present. Prometheus Books.

Mezirow, J. 1991: Transformative dimensions of adult learning. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass higher and adult education series.

McCrystal, P. 2000: Developing the social work researcher through a practitioner research training programme. Social Work Education 19 (4) pp. 359–374.

Miettinen, R., Samra-Frederichs, D. and Yanow D. 2009: Re-Turn to Practice: An Introductory Essay. Organization Studies 2009;30;1309.

Kaarina M. 2008: Vuorovaikutus. Dialoginen asiakastyö. Helsinki: Edita.

Nowotny, H. 2003: Democratising expertise and socially robust knowledge. Science and Public Policy; 30 (2), 151-156.

Okely, J. 1992: Anthropology and autobiography. Participatory experience and embodied knowledge. In Okely, J., & Callaway, H. (Eds) Anthropology and autobiography. London, New York: Routledge.

Parkkinen, J., Puukari, S. 2005: Approaching worldviews in multicultural counselling. In Launikari, Mika & Puukari, Sauli (Eds.) Multicultural guidance and counselling. Theoretical Foundations and Best Practices in Europe. Jyväskylä: Centre for International Mobility CIMO and Institute for Educational Research.

Ramian, K. 2004: Praksisforskning som laeringsrum i socialt arbeid. http://www.ceps.suite.dk/laeringsrum%20i%20praksis.pdf

Reason, P., Torbert, W. 2001: The Action Turn: Toward a transformational science: a further look at the scientific merits of action research. A further look at the scientific merits of action research. Concepts and Transformation 6(1), 1-37.

Saurama, E. & Julkunen, I. 2009: Käytäntötutkimus lähestymistapana (Practice research as an approach). In Sosiaalityö ja teoriat (Social work and theories). Mikko M., Pohjola, A, & Pösö, T (eds). Jyväskylä: PS Kustannus.

Satka M., Karvinen-Niinikoski S., Nylund M. and Hoikkala S. 2005: Sosiaalityön käytäntötutkimus. (Practice research in social work) Helsinki: Palmenia Kustannus.

Schatzki, T. R., Knorr-Cetina, K., Savigny E. 2001: The practice turn in contemporary theory. Routledge: London and New York.

Schön, D. 1983: Reflective Practitioner. How Professionals Think in Action. New York:Basic Books.

Shaw, I. 2005: Practitioner Research: Evidence or Critique? The British Journal of Social Work, 35(8) pp. 1231–1248

Shaw, I., Bryderup, I. 2008: Visions for Social Work Research. In Inge B. (ed) Evidence Based and Knowledge Based Social Work. Research Methods and Approaches in Social Work Research. Danish School of Education. Aarhus University.

Shotter, J., Gustavsen, B. 1999: The role of dialogue conferences in the development of learning regions: doing from within our lives together what we cannot do apart. Centre for Advances Studies, Stockholm School of Economics.

Sjöblom, S. 2008: ”Har de blivit hjälpta så att de blivit stjälpta?” En studie i socialarbetets potential och gränser inom handikappservice. FSKC rapporter 2/2008.

Strauss, A. L. 1993: Continual Permutations of action. New Brunswick and London: Aldine Transaction.

Styhre, A. 2003: Book review: Schatzki et al The practice turn. Scandinavian Journal of Management 19 (2003); 395-398.

Thomas, N. O., Kane C. 2000: Discovering what children think: Connections between research and practice. British Journal of Social Work 30 (6); 819-835.

White, S., Riemann G. 2009: Researching our own Domains: Research as Practice in Learning Organizations. In Shaw, I.,Briar-Lawson,K. Orme, J. and Ruckdeshel, R (eds) : The Sage Handbook of Social Work Research. Los Angeles, London, New Delhi, Singapore, Washington DC: SAGE.

Vinterhed, K. 1977: Gustav Jonsson på Skå – en epok i svensk barnavård. Stockholm: Tiden

Wittgenstein, L. 1980: Culture and Value. Oxford: Blackwell.

Author´s Address:

Ilse Julkunen

Professor

Helsinki University

Department of Social Policy

Snellmaninkatu 10 (Box 18)

00014 University of Helsinki

Finland

Tel: ++358-(0)9-191 24577

Fax: ++358-(0)9-191 24564

Email: ilse.julkunen@helsinki.fi

urn:nbn:de:0009-11-29288