By Dint of History: Ways in which social work is (re)defined by historical and social events

Jonathan Parker, Bournemouth University

Magnus Frampton, Universität Vechta

1 Introduction: Disputed beginnings of social work history

In 1940, the cultural critic Walter Benjamin penned his theses on the concept of history. In the ninth thesis, he famously takes inspiration from an artwork that he had owned for 20 years, Angelus Novus, by the painter Paul Klee. Intrigued by the angel’s peculiar glance, Klee’s ‘new angel’ becomes for Benjamin the ‘angel of history’. Benjamin contrasts how we see history and how the angel sees it:

“Where we see the appearance of a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe, which unceasingly piles rubble on top of rubble and hurls it before his feet” (Benjamin, 1968, pp.257-258).

The angel of history tries to restore order, but cannot, for Benjamin sees him as being blown by a storm from paradise.

Benjamin’s ambivalence towards the causal claims of historians, symbolised by this image of the storm of progress overwhelming the angel, expresses a turn away from both Enlightenment and earlier Marxist views of history. The angel is powerless and unable to restore order. Progress, previously seen as a gentle and linear continuous path, is now portrayed as a violent storm. We may relate to Benjamin’s image when grappling with the profession’s historical continuities and discontinuities. The turbulence of the storm experienced by the angel, blowing him wildly, is a chaos experienced when trying to find and make order in the global progress of our profession. Our professional identity as social workers is shaped by the historical, political and socio-political backgrounds of our work, contexts that sweep us in bearings not always of our overt choosing and determine what we understand by the slippery concept of ‘social work’. This paper considers some of the ways in which historical and political events and shifts have (re)defined the profession and, thereby, our professional identity. It calls us to be mindful and critical of our context and to acknowledge the complex and shifting understandings of social work.

History, like social work, represents a contested discipline or nexus of fields of study that attract competing explanatory frameworks. Looking back at social work’s history we gaze through a lens burnished with development and change, through a prism of historical knowledge. Ontologically, we choose our reference points and see them in preferred ways; our historical knowledge represents the unspoken and accepted discourses we have created and which have created us. These, in turn, are constructed by our chosen epistemologies which delineate what we accept as our truths making our excursus partial and open to challenge. We do not always see or acknowledge these influences.

Payne (2005) argues cogently that a continuity model of historical development is fraught with problems, and change and continuity actually intertwine helix-like with some things remaining and others disappearing. Traditional histories of social work, Payne states, tend to be celebratory, hindsight-biased, Euro- and ethnocentric, gender-biased, neglectful of people-served and institutionally-constrained (Payne, 2005). However, social work is itself complex and hard to define. As regards its histories, which are, themselves, culturally bound, we can say only, ‘it began at various points in the past’. It is difficult to be more precise than that because pinpointing social work’s origins demands defining it as a homogenised practice and this, as we note, is contested as well as privileging the Enlightenment and progressive view of history. We can see a confluence of human-to-human compassion, the embedding of religious charity and obligation, and political developments and the codification of compassion towards both agentic and structural well-being or the enhancing of economic function and productivity depending on the political stance taken (Ife, 1997; Finkel, 2018). These phenomena underpin social work in various countries, at various times. This is clearly shown in Allen et al.’s (2015) comparison of the redistributive community-based social work of Cuba and the clinical focus of social work in the United States. However, despite the recognition of diversity, they argue that the profession can unite across countries because of the focus on social and civil conditions, equity and social justice. Adopting a different perspective, Payne (2005) locates social work’s emergence, from the 18th and 19th centuries, in industrialisation, concomitant urbanisation, the bureaucratisation and organisation of women’s welfare and charity work and the increased responsibility of the state to maintain social order.

The contemporary global definition of social work (IFSW/IASSW, 2014) offers us a lens to examine the past anachronistically. We are hindsight-biased and, it may be argued, ethnocentric, despite the careful negotiation of the 2014 definition and criticism of its precursor (Banks, 2021). For instance, the turn towards ‘safeguarding’ in UK social work stems largely from a history of popularist political responses to the deaths of children caused by parents and guardians as much as from a desire to protect people from violence (Parker, 2020b). As a starting point, however, the definition represents a ‘regime of truth’ that, if we consider it carefully, allows us to explore social work’s chequered, contested and fraught histories (Foucault, 1991). The ‘truths’ contained within the definition, although themselves open to plurivocal interpretation, order and prescribe some of the ways in which the discipline of social work is currently understood and by which the past is interpreted (Allen et al., 2015). In this paper, we will consider some of the discontinuities and continuities in this emerging set of systems for the organisation of social work focusing, in particular, on the UK and Germany.

Lachmann’s (2013) suggestion that the underpinning rationale of historical sociology is to lay bare the conditions that led to significant changes and developments in human history is useful, but including the importance of the qualitative and the biographical gives context and meaning to the histories of social work that often act at the level of individuals (Oakley, 2019). Thus, we shall be looking for understandings of how things changed, not simply what led to these transformations, but what resonances these have for understanding social work today in Germany and the UK. We will look at four key transformations as examples showing how engagement with history shapes social work thinking and practice: (1) Poor Law beginnings and continuities in characterising British social work, (2) the impact of political turmoil and foment from the National Socialist period in Germany, (3) the contemporary turn towards indigeneity in previously colonised areas of social work, and (4) the discomforting rise of political populism. These examples will be framed in the context of power relations.

2 Turning wheels leave (some) tracks

In a recent historical excursus through global welfare practices, Alvin Finkel (2018) demonstrates human societies’ enduring concern with the well-being of others who are disadvantaged, made vulnerable or seen as weaker in some way. Whilst our contemporary vantage point is steeped within organised and politicised welfare systems, Finkel’s portrayal shows its ubiquitous and embedded aspects; welfare is part of the human condition and our modern ‘social works’ represent a codification of it. Such an analysis might be construed as adopting a social evolutionary and potentially functionalist perspective, whereas it may be better to identify some of the underlying discourses constructed by these historical changes, as it is these discourses that mould the social practices associated with them. We shall attempt to show this through a range of examples in social work’s history in Germany and the UK.

3 Poor Law and its reforms

The English Poor Laws represent important pieces of socio-political legislation that offer a window into some of the conflicted purposes of welfare and presage, to an extent, aspects of what we now know as social work. The history of the laws is long, reaching back to the time of Richard II and, for some even further back still (Charlesworth, 2010). The laws addressed the ravages of plague, economic crises, failed harvests, and the perceived risks associated with migrant workers, foreign to the close-knit communities they were attempting to enter, and potentially disease-carrying or dangerous.

Based on economic and social need, and reinforced by economic and social anxieties, the Poor Laws promoted a nascent social policy and constructed the discourses by which people were, subsequently, valued, developing over time the acceptability and non-acceptability of welfare. Appeals for assistance (applications for welfare so to say, in our modern language) carried risks to the needy person (applicant). A notorious feature of the earlier UK poor laws was their punitivity. Punishments for the vagrant migrant poor in the Tudor Poor Laws included ear boring, branding with a hot iron, and whippings. The scars of the flogging, the branded V mark, the burnt right ear, became stigmata for their carriers: visible signs of their unacceptable request for help (Piven and Cloward, 1993). These marks of stigmatisation would have been be reinforced by other markers, such as the vagabond’s non-local dialect, lack of local knowledge and potentially foreign habitus. In Britain, the idea that some of the needy should be stigmatised is thus as old as organised welfare itself (O’Hara, 2020). Welfare recipients are to be ‘not like us’, they represent the other, with whom we should not identify. The physical, social and emotional stigmata associated with welfare recipients continues into the present day through media reports, television and popular thought and those working alongside such people experience stigma by association (Parker, 2007; Jones, 2020; O’Hara, 2020). This shows a deep-rooted thread permeating history and linking a punitive and regulatory past with the present.

Poor Law legislation was anchored on the concept of judging the needy and separating them into two categories: the deserving and the undeserving poor. This process of judging, ‘assessing’ in our modern parlance, would have been a key task of the parish overseers of the poor in Elizabethan Britain, later Victorian parish workhouse officials, or indeed, in a marginally more benevolent sense, the Charity Organisation Society’s ‘friendly visitors’ administering outdoor relief, following their own ‘scientific’ methods. We could argue the net effect of these massed individual judgements was the creation of a split society in Elizabethan and Victorian Britain between deserving and undeserving paupers. This dual society, in Britain and other liberal regimes, has continuing consequences for the social work profession, whose clients are invariably caught on the wrong side of this split, and has led to social workers being stigmatized by association and attracting opprobrium (Parker, 2007; 2020b).

Alongside moral judgements about the deservingness or undeservingness of the needy individual, the primacy of ‘setting to work’ and the subsequent establishment of workhouses and similar institutions draws our attention to how the English tradition of welfare is embedded in economic rationalities. Some of the needy, who threaten to drain the parish of resources, can, if managed well, be restored to economic productivity. This economic logic sidesteps ethical or human rights perspectives, instead using profitability or net cost minimisation as its rationale. The persistence of such welfare discourses means that contemporary investment in projects promoting social justice, for instance the UK’s Sure Start centres, might instead be sold to the electorate along economic argumentation lines, stressing, for instance, the promise of future fiscal advantage for the State. Indeed, the discussion paper Every Child Matters (Chief Secretary to the Treasury, 2003) promotes achievement, contribution and economic well-being as goals for children which can be read in this way. Such examples illustrate how social work’s self-defined mandate (based on ideas of social justice) may be in conflict with an externally imposed societal mandate (based on ideas of economic rationalisation). This external social mandate has been passed down over centuries, is based on the welfare rationalities of the past, and is therefore not oriented on 20th century perspectives such as solidarity, human rights or human emancipation.

However, such a reconstruction of the roots of modern social work, presenting a continuity taken for granted in the Anglophone world, might be contested elsewhere. Although the broad global definition of social work is formally accepted in the UK, a more everyday British understanding of social work practice may place it in a narrower local authority, case management context: managing the vulnerable and poor, individual by individual, with a supportive and protective agenda. In Germany, in contrast, this understanding only corresponds to one facet of that discipline known as Soziale Arbeit. The history of this broader German profession displays a stronger tradition of faith-based support rather than secular assistance, and we may argue that this has strengthened German practice’s links to traditions of help rather than control (Lambers 2018). Indeed, the German term Soziale Arbeit may be best translated as ‘social care’, encompassing as it does a broader range of caring/helping interventions, methods and client groups. Moreover, the stigmatising of social work clients is seen more critically in the German context because of the consequences of engineered stigmatisation processes during the country’s darkest historical period, which we shall return to later in this paper.

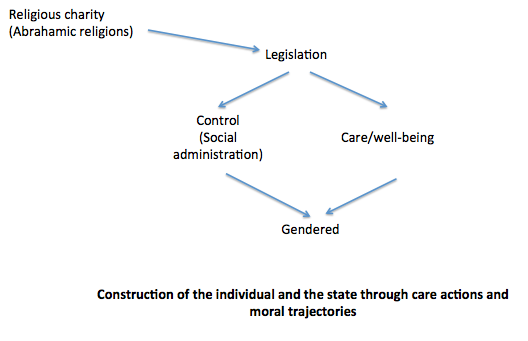

Religious charity in the Abrahamic religions underpinned the development of legislation, ordering the care and control of vulnerable groups, and the gendered place of caring. Both the individuals involved (care provider and care receiver) and the state were constructed through care actions, actions which became mediated through the moral binary trajectories of punishment/control/blame and virtue/care/good. New professional roles developed in the mid 19th century, and the growth of organised welfare supported women’s labour market participation. In Germany, Henriette Schrader-Breymann identified an opportunity for women to cast a professional role for themselves, practising ‘spiritual motherliness’ wherever there are the needy in ‘body and soul’ (Schrader-Breymann, 1962 (1868), p.11, cited in Kuhlmann, 2008, p.47). Whilst this taking advantage of such perceived ‘motherly’ female strengths opened professional doors for middle-class women, the legislation and social administration of the time displayed an increasingly gendered approach to social organisation. Control and coercion via social administration were soon connected with masculinised approaches, whilst caring, well-being and nurturing were associated with female-led welfare and diminished in their standing, as seen through history (Terpstra, 2004; Gilligan, 2016) (see Figure 1).

|

Figure 1

The ambivalence of welfare security and stigmatization of those receiving support has been challenged in UK social work by developing radical social work approaches, continued today though SWAN (the Social Work Action Network https://socialworkfuture.org/), and through standing alongside the marginalized and oppressed whilst attracting stigma by association (Parker, 2007; 2020b). Contemporary German social work has been influenced by different socio-political histories to which we now turn.

4 Political turmoil

In the 1920s and 1930s, a range of conflicting positive and problematic developments can be seen in the fledgling organisation of social work, especially on the Continent. The birth of what has become the International Association of Schools of Social Work, the International Federation of Social Workers, and the International Council on Social Welfare, all linked to the 1928 First International Conference of Social Work in Paris, represents one of the highs. The lows are, however, represented by social work’s mundane adoption of and alignment with National Socialist racial ideology (Lorenz, 1994; Johnson and Moorhead, 2011).

Early 20th century continental European social work developed rapidly, with many key figures’ work being informed by the movements of the time: the social democracy movement, the peace movement, the women’s movement, and the public interest in international relations and social development. No figure illustrates this better than the German social work pioneer Alice Salomon. Her international stance drew on Mary Richmond and Jane Addams’ work in the United States (Kuhlmann, 2007), which in turn had connections with the Charity Organisation Society and Hospital Almoners as well as the Settlement Movement in the UK. A key figure at the Paris conference, Salomon shaped the development of the nascent social work profession in diverse ways. As a social work educator, she founded the first women’s social work school in Berlin in 1908. Salomon’s positions and idea of social work still look modern today, and seem almost a precursor of the global definition of social work. Her views were shaped by her research on social problems: she developed an acute awareness of the structural causes of clients’ difficulties, and the life conditions in which they found themselves. Her ideas of social justice were informed in dialogue with the social democracy movement, but she might be best described as a liberal social reformer, using a human rights orientation centred on the dignity and equality of all people regardless of class, gender or race. Salomon was a critic of economic liberalism, being concerned with its incompatibility with her ideas of social justice. The human being for her is a social being, to be understood in their societal context and yet more than just a product of that environment (Kuhlmann, 2000, pp.223-237). Kuhlmann (2000, p.320) concludes her monograph on Salomon’s life and work by noting her status as “(…) the first protagonist of a feminist theory of social work” on account of her commitment to focusing on the lifeworld of the woman within her theory building.

Although the most famous figure of this period, Salomon was in no way alone. Hertha Kraus’s work in Germany and later the US combined interests in socialism and Quakerism (Bussiek, 2003). Helena Radlinska’s belief in community education led to her developing a social pedagogy in Poland that could be regarded as experiential pedagogy, pioneering an early form of reflective practice in the process (Lepalczyk and Marynowicz-Hetka, 2003). Salomon, Kraus and Radlinska, are examples of figures in European social work history that were transformative in developing social work understandings of social justice, and using human rights as an orientation point, concepts that are now embedded and unquestioned in social work. A shift from an individualised system of stigma, blame and hierarchical responsibilities to a socially conscious and overtly politicized social work took shape.

The professional advances of German social work in the Weimar Republic period, and its early development as a human rights profession was a project bitterly interrupted by the Third Reich’s seizing of power. Social worker complicity in the crimes of the National Socialists, and also their resistance to them, are well documented in Germany (see for instance the volumes edited by Otto and Sünker, 1986, and Amthor, 2017). Indeed, every German social work history textbook has an extensive chapter, reconstructing social work’s implication in the atrocities of the period (Kuhlmann, 2008, Hering and Münchmeier, 2014, Rathmayr, 2014).

In the National Socialist period, social welfare was replaced with ‘Volkspflege’: the welfare for the (German) people, or more specifically, for the German ‘people’s community’ (Volksgemeinschaft). This was based on its own (pseudo) theoretical foundations, the National Socialist ‘race theory’ and their eugenics-based theory of genetic inheritance. The plural landscape of German welfare associations that had developed in the proceeding decades fragmented, the work of those civil society organisations largely being replaced by a dominant state organisation, the Nationalsozialistische Volkswohlfahrt (National Socialist People’s Welfare). Child raising and education in particular were colonised by the National Socialists. Family welfare, and especially the Hiltler Youth and its female sister organisation the League of German Girls, were powerful vehicles for the spreading of their ideology.

Social workers’ capacity to resist were highly limited. As Kuhlmann (2017, p.53) notes, the mostly female welfare workers were rarely in positions of power themselves. Many social workers were themselves forced to flee the National Socialists, due to their Jewishness or their political beliefs. For many, however, exile did not interrupt their work: Walter Friedländer, for instance, moved first to Paris, then the States, but in each case did welfare work with refugees and exiles from Germany. His roots in the peace movement and his social democratic politics shaped his work (Biebricher, 2017). Polish social worker Irena Sendler rescued Jewish children in occupied Poland, risking life and limb to smuggle them out of the Jewish ghetto (Wieler, 2008). Her sense of solidarity with Jewish people had been inspired by her father’s work as a doctor, treating all patients, regardless of their race or background. Already as a student, she broke regulations to sit on the same bench as her Jewish co-students, and in her later work in Warsaw’s Jewish ghetto, she wore the Star of David in solidarity with her fellow human beings (Sagebiel and Amthor, 2017).

However, the stark realities of Janus’s two faces are presented in the ways in which social workers of this period were also drawn into the extreme ramifications of social eugenics and in ways that Bauman (1989) explained the ordinariness of being part of National Socialist atrocities through the quotidian bureaucratisation of social administration. Johnson and Moorhead (2011) explore the influence the social eugenics movement had on practices that led to the assessment of the viability for life of children with a range of disabilities and mental health problems, and so-called deviancies, that led, subsequently, to these children and young people being killed (Kunstreich, 2003). The long-term goal of this practice, in accordance with the National Socialists genetic theories of deviance, was to create that totalitarian fantasy of a ‘society without social work’, since the very existence of the needy would be prevented. Barney and Dalton (2008) describe the involvement of social workers in the assessment and selection of ‘non-viable’ children and young people using a partly ironic notion of ‘social work-in-the-environment’ which we may perhaps understand in Bourdieusian terms as a structured structure whose enduring dispositions are influenced by assumed and unquestioned social eugenic discourses promoted by National Socialist ideology (Bourdieu, 1977).

After WWII, German social work had to start anew. In terms of theory, we might speculate that this break explains German social work’s turn away from the medicalised theory and technocratic concepts that continued to influence Anglo-Saxon practice. Although imported concepts from the discipline of medicine have found application in Germany (for instance care/case management and evidence-based practice), it could be argued that these medicalised and natural science-founded concepts took root much less vigorously than in the Anglophone world. Indeed, such concepts were often met with vociferous resistance (see for instance the collections of papers on evidence-based social work edited by Otto et al., 2009 and 2010). Similarly, in organisational terms, Germany returned to its earlier reliance on the civil society welfare associations, each bearing its own independent religious or political value base, to carry out the bulk of social work practice. Today, Germany has one of the most organisationally plural landscapes of agencies to be found anywhere.

The Marshall Plan facilitated the rebuilding of post-WWII Europe. It supported the welfare of many, but it did so as a means of control through beneficence, not dissimilar to the ways in which the Poor Laws were operated. Human compassion was utilised to reinforce a regulatory and neo-imperial mechanism to embed victories. Whilst the Marshall plan was wide ranging, the welfare element created microcosms of US social welfare carrying the discourses of US influence. The programmes accompanying the Marshall Plan promoting American culture and technical expertise had colonised the German professions. The émigré Walter Friedländer, for instance, worked with the US military government on social welfare questions immediately at the end of the war, and he later visited Germany as a Fulbright scholar (Biebricher, 2017). Similarly, German-born Gisela Konopka repeatedly came to train and lecture. Post-war German social work thus displayed a natural deference to US discourses, with translations of popular US social work texts becoming common on reading lists. The US triad of classic methods at the individual, group and community levels become standard. There is a parallel here with the way in which the aid currently given to Global South countries through the Global North supranational organisations and INGOs propagates Global North concepts of social services, which we shall investigate further below.

German society in the post war economic miracle years was still characterised by a reluctance to reflect critically on the atrocities of the recent past. This did not change until the late 1960s, with the new social movements presenting a fertile ground for German social workers’ reflections on the historical context of their practice. By this time, German rather than US-derived social work theory was re-establishing itself: as Sozialpädagogik at the research universities, and as Sozialarbeit, asserting itself as a new academic discipline at the newly founded Fachhochschulen (polytechnic universities). Social work in Germany thus has ingrained disciplinary ties to pedagogy. This pedagogical grounding of German social work facilitates discourses drawing on the disciplines’ Romantic and Enlightenment roots. Having been confronted with barbaric National Socialist pseudo-theories, and then imported US theories in the mid-20th century, Germany ended the 20th century with a distinct social work theory base of its own (see Lambers, 2018, Engelke et al., 2018, or Erath 2006 for comprehensive introductions).

Germany’s history has not only shaped its contemporary social work methods, theory base, and organisational forms. A conscious reaction to the country’s totalitarian past has given some German practitioners legal rights they may not enjoy elsewhere. Some German social workers have managed to avoid involvement in informing on particular clients, so as to prevent their implication in the labelling and criminalisation of these individuals. The German Code of Criminal Procedure, section 53, protects certain workers working in pregnancy advice and drugs counselling services (alongside with member of other professions such as the clergy) from having to make disclosures in court. This sensitivity to the right to and limits on confidentiality in a non-judgemental helping relationship is characteristic of practice in a country still actively coming to terms with its totalitarian past.

The professional conflicts in Europe’s past may be taken forward to the present day, where there is a less extreme, but still pernicious and continuing influence on social work, caught sitting uneasily between the State and the ‘Other’ (Lorenz, 1994; Day 1979). A contemporary instance of this uncomfortable tension between care and control is seen in UK social work. Just as Peukert (1987) relates the requirement for social workers and other professionals to report children with disabilities or emotional problems, social workers today must report children and young people in particular who may be ‘radicalised’ towards extreme thinking (McKendrick and Finch, 2017; Parker and Ashencaen Crabtree, 2018).

This dark and complex period in European social work’s history has thus resulted in a dual legacy. Firstly, the positive adoption of global elements of social work – a fraught and difficult concept – and secondly a recognition of the tightrope walked by social workers negotiating between care and control, person and State, fluid subjects and establishment norms. These examples require illumination to promote the necessity of questioning, challenging and navigating the difficult terrain of state sponsored social engineers and regulators, which demands that social workers remain continually prepared to ‘bite the hand that feeds’; that is, hold State, organisation and employers to account.

Whilst power acts two ways in these first two examples – resistance to state control and the imposition of state control – we find a resistance against ‘exported’ social work models during earlier colonial times which exerts a pressure to change social work in former colonised and colonising countries. It is to this we now turn.

5 The indigenous turn

The historical development of social work in different countries highlights Western, including German and UK, privilege in those stories (Payne, 2005; Frampton, 2019; Parker, 2020a). Histories often show the Poor Law influences, but also the community-based social justice models of the Settlement movement. Colonial influences pervade through post-colonial accounts of social work development (Parker, 2020a). Western privileged histories represent normative models with alternatives attracting labels of deviance that, unfortunately, have sometimes led to a desire to emulate these Western models and to foster ‘professional imperialism’ (Midgely, 1981; Sylvester et al., 2020). We include discussion of the turn to indigeneity here because of the reaction against Western social welfare development in non-native locations, a reaction against power imbalances, and something that is moulding our conceptualisations of social work globally and locally.

The turn to indigenous knowledges and practices as the basis for ‘authentic’ localised social work has resisted normative models and created a positive transformative deviance (see Ling, 2007). First Nations social workers in Canada and Australasia have rejected the imposition of uncritically transferred Western models of social work (Gray et al., 2013). This transfer of practices may often, as Frampton (2019, p.131) states, forget ‘the contexts’. Appreciating the contexts is bound with a sense of the historical and this must include a post-colonial lens in countries that were former colonies and a critical understanding of indigeneity otherwise.

There are complex questions to discuss and a balanced approach is needed which acknowledges the benefits from some transfers of knowledge and practice and the disadvantages of some localised cultural variants; normative versus indigenous does not represent a valid binary distinction to follow. An approach that acknowledges both local and shared global factors is promoted within the 2014 definition, which was formed within a crucible of intense debate. The importance of historical trends that label pejoratively (such as deserving and undeserving), inspire behaviours that are morally reprehensible (reporting and assessing for punitive or fatal treatment those made vulnerable by a society) must be countered. This can be done by recognising the strides made, by Alice Salomon and others, towards international cooperation, acceptance and agreement on key concepts of social justice and human rights, however contested and locally interpreted these remain.

Acknowledgement of the ways in which social work has colonised Indigenous lifeworlds is a first step towards decolonising social work, but requires a complex and multi-layered approach, which is transformatory rather than oppositional. Decolonisation cannot simply be the dismissal of the past but must entail a positive recognition of the value of the local in the contexts that have developed through history. If we look at South African approaches to childcare we can see that legislation has its roots in Western ethnocentric practices. However, we also note the growth of Ubuntu as a guiding concept of collective care (Davey et al., 2014). Thus, colonial histories and local knowledges are combined for a practice that is authentic in context.

The benefits of Indigenous social work are not just to be felt in those countries that suffered a colonisation of their social work. The Indigenous turn is enrichening global social work practices. The shift is discursive, that is, our concepts and orientation points are broadening and morphing. Social justice is to be understood as global justice, including global cognitive justice: the acknowledgement of non-Western knowledges, ‘epistemologies of the South’ (Santos, 2016). Human rights are to be understood as not just those first and second generation rights upon which Western constitutions are based, but also the collective and community third generation rights. For theorists and practitioners in the Global North, the acquisition of this new language represents a challenge. Santos warns that Eurocentric critical theory does not understand the ‘counterhegemonic grammars and practices emerging in the global South’ (Santos, 2016, p.41).

This shift in thinking is already happening. As an example, the updated global definition underlines the role of collective responsibility in underpinning social work. Whilst the late 20th century saw reactive individual help dominating social work methods, and the importance of group and community approaches diminishing, there are signs that this might be reversing. Early 21st century German social work experienced a ‘spatial turn’, with Sozialraumorientierung (social space orientation) dominating discourses: a shift from ‘case’ to ‘place’ (see for instance the edited collection by Budde et al., 2006). Here, the focus is on building up neighbourhood facilities, services and networks, and there is some overlap with older community development discourses. Nonetheless, such new community orientations can encourage the combination of structural improvements to reduce the effects of poverty on a neighbourhood, with universal services with a preventive function. The Frühe Hilfen (early help) in Germany, effectively a more professionalised and politically supported version of the British Sure Start project, illustrate this well. A shift from individual responsibility to community responsibility, leads to a shift in focus from individual need to community need, just as the 20th century focus on individual human rights is slowly being superseded by a 21st century consideration of collective, group human rights. The young discourse on green social work (Dominelli 2012) is a further example of social work inspired by this shift. In the UK, we see social work championing the multicultural and rights to choose, but find this bounded by a sense of social justice for all.

6 Politics, politicisation, and populism in social work

Alongside indigenisation, globalisation and neoliberal marketization mark the recent history of social work. There has been a homogenisation of action and the development of underlying social discourses of normative behaviour and thought. In the main, this represents a device of the Global North imposing its will imperiously on the Global South. Global North norms and actions are presented as universal and unquestionable, especially from a UK and North American perspective. From a social work angle, we can identify institutional, economic and discursive elements to this imperialism, and, of course, the three interact. Institutions are aligned with economic rationalities, and support is now delivered within an economic marketplace of agencies. Welfare in general and social work in particular, in the West, has a theoretical foundation determined by hegemonic discourses, such as managerialism (Ökonomisierung in Germany) and the positivistic clinical approaches it is compatible with. The neoliberal reforms are, in turn, shaped by shifting political currents. While the influence of right-wing populism and ‘anti-establishment’ protest has been particularly striking in recent years (and has accelerated damage to our welfare states), we can actually detect a slow rise over a period of many decades, albeit initially in the more superficially wholesome form of anti-government (‘nanny-state’), ‘welfare scroungers’ (Faulheitsdebatte in Germany) and neo-conservative political discourses.

A British example illustrates recent developments well. There has been an increasing focus on safeguarding and social work that is determined by legislative power. Social work has been redefined as a practice concerned predominantly with social regulation and control. The circle is turned, and a return to political elite moralisation underpins social work practices, just as seen in the earlier Poor Law and social welfare initiatives. This binary moralisation between ‘good’ and ‘bad’/’deserving’ and ‘undeserving’ has been readily adopted by populist and far right groups playing on assumed and unspoken ‘truths’. This is evident in the pronouncements of David Cameron, as leader of the opposition in 2008, and the response by Ed Balls, then Secretary of State for Children, Schools and Families, following the publication of the inquiry report into the death of 17-month-old Peter Connelly. Political responses followed popular mythologies to blame and scapegoat social work as a means of deflecting attention from structural and governmental responsibilities (Parker, 2020b). The recent report (Turner, 2019) into the deaths of Dylan Tiffin-Brown and Evelyn-Rose Muggleton is balanced in highlighting ‘professional failures’ (albeit without fully acknowledging the context of resource constraint), but recognising brutal acts are not always preventable by social workers and others. However, the pervading scapegoat discourse is employed by the Department of Education who aim to put in place a children’s commissioner to drive improvements and to prevent such tragedies occurring in the future. Whilst on the surface this is admirable, it is an act of politicisation of a tragedy designed to offset the need to accept structural responsibilities (Parker, 2018; 2020b; Samuel, 2020).

7 Core themes

In both German and UK social work, the key elements within the historical turns we have identified oscillate around power relations such as the development of coercive elements of social administration – the Poor Laws and amendments to them – designed to control the populous as much as to ease distress; various transfers of knowledge, skills and values and the potential continuation of Western and capitalist dominance, through colonial and neo-imperial systems of people management; and, more locally, ensuring the fitness and compliance of the workforce through welfare state provision post-WWII.

Social work history is dynamic and in order to challenge, reject or replace these notions of political and social control and to co-construct something new, we need to understand how the concept of power is being used. We can find a model in Foucault’s approach to power as relational rather than as a commodity imposed by the stronger to repress and control the weaker, and in his concept of discourse as a means of resisting.

“We must cease once and for all to describe the effects of power in negative terms: it ‘excludes’, it ‘represses’, it ‘censors’, it ‘abstracts’, it ‘masks’, it ‘conceals’. In fact power produces; it produces reality; it produces domains of objects and rituals of truth. The individual and the knowledge that may be gained of him belong to this production.” (Foucault 1991, p.194)

If seen in this way, as Gaventa (2003) states, it is a creative rather than inherently a negative force. Foucauldian notions of power represent a major source of social discipline and conformity. His depictions of different forms of power indicates a shift from ‘sovereign’ and ‘episodic’ exercise of power, traditionally centred in feudal states to coerce their subjects into appropriate ways of behaving and organising, to ‘disciplinary power’ or power based on perceptions of surveillance that he suggested were seen in the social administrative systems created in 18th century Europe, such as prisons, schools and mental hospitals and transferred into the social services organisations of the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries (Foucault, 1991). These disciplinary systems of surveillance and assessment required neither force nor violence to produce conformity, as people learned to discipline themselves and behave in assumed ways because of the surveillance and social assessment that they perceived as operating in society.

Power and resistance seen in this way was not something that had to be taken from others but rested in the illumination achieved through recognising and questioning received discourses. This happens when received forms of social work are challenged by alternative indigenous discourses; when the dominance of Western individual and clinical practices are recognised and challenged by a corrective of family and community practices; and where the safeguarding practices of the UK are added to by campaigning and social justice practices that identify the roots of safeguarding needs within the pathologies of society, rather than within individuals.

A traditional unquestioning approach to power as a commodity held by the stronger, who control the terms of the argument, is highlighted in the coercive imposition of social control and popular demonising of behaviours shown in populist and far right discourses. However, an inherent personal/group morality can expose these discourses and make manifest alternatives.

The interest groups in society who, from philosophy and socio-economic power bases, created the discourses that fostered the concept of deserving and undeserving welfare recipients enjoyed the material resources and social organisational structures to reinforce these mechanisms. Through the processes of internalisation, however, disciplinary and bio-power that was once imposed from outside has become the taken-for-granted understandings that influence how social services are organised at a structural level and practised at an individual level (O’Hara, 2020).

It is only by exposing the discourses to critique that alternative, resistive discourses can change and reconstruct social work. We can do this in two ways. Firstly, in the process of naming the prevailing discourses themselves, and, secondly, by surveillance through social work’s focus on social justice and human rights, which themselves must remain mutable and fluid concepts. We can apply this approach to the examples of UK safeguarding practices, and Indigenous knowledge in social work as discussed above.

The safeguarding discourse in the UK has been influenced by an unspoken binary assumption of acceptable and unacceptable social practices, influenced by power-knowledge and tradition in the policy process and organisation of services. This binary assumption, an ingrained relic of four hundred years of managing the poor, brings with it the danger of practices of isolated individual protection. Individuals in difficulties are treated atomistically, without also recognising the need to simultaneously challenge the wider structures that create the conditions for abusive situations to develop. Such an analysis may be criticised for removing blame from individual abusers. However, by avoiding such an analysis we would remove blame from the structures of government, social service organisations and those with the power to set the terms of the argument. In this case, being mindful of social work’s commitment to collective responsibility (added to the global definition of social work, IFSW/IASSW 2014) and social justice can help us break from the individualistic and binary assumptions of the past.

The indigenous turn exemplifies the naming of colonial power practices and inauthentic impositions that were resisted, by demonstrating the wider applicability, acceptability and authenticity of local practices and approaches. When these are distilled within the context of social justice and human rights, they allow for a balanced appreciation of practices. Moreover, this broadening of local social work approaches can inform global social work, enrichening it with fresh orientation points, which are not shackled to our profession’s Western-dominated past.

The project of understanding our profession’s history can thus be seen as part of an emancipation project, one that fits well with the openings and open-endedness of the Indigenous turn. For global social work to be non-Eurocentric, its values must be truly meaningful in the Global South. This may mean that terms such as good living and community self-determination enter the core text of the next international social work definition. Ideas from Western social work (most of which come from European traditions of the natural and human sciences) may be locally rejected, but this rejection can be viewed positively, as the language we take for granted changes.

Let us return to Benjamin’s angel, the starting point for our considerations of social work histories. Santos (2016), whose epistemologies of the South we considered above, also examines Benjamin’s angel to help understand the emergency of the present, a time of transition. Mindful that our current times are also laden with disaster and injustice, Santos proposes replacing the theory of history of modernity with another:

“(…) one capable of helping us to live this moment of danger with dignity and to survive it by strengthening our emancipatory energies. What we most urgently need is a new capacity for wonder and indignation, capable of grounding a new, nonconformist, destabilizing, and indeed rebellious theory and practice.” (Santos, 2016, p.88)

Giroux (2011), writing from a US context and addressing the struggle to maintain hope in the social state, also uses the symbolism of Klee’s painting. For Giroux the angel is still a contemporary image, in this case blown from behind by horrors of another sort: the collapse of social bonds, the replacement of a welfare state with a ‘punishing state’, and the rise of an authoritarianism that stifles public discussion on these developments.

For Giroux, Benjamin’s angel marks a turn away from the idea of a smooth progress of history, but not a departure from the idea of understanding history. Perhaps the angel reminds us, with caution, of the challenge, the exertion, and the trials of understanding history in difficult and turbulent periods.

References:

Allen, J.A., Bailey, D., Dubus, N., & Wichinsky, L. (2015). The interrelationship of the origins and present state of social work in the United States and Cuba: The power of a profession to bridge cultures. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 25, 18-25.

Amthor, R. C. (Ed.) (2017). Soziale Arbeit im Wiederstand! Fragen, Erkenntnisse und Reflexionen zum Nationalsozialismus. Weinheim: Beltz Juventa.

Bailey, R., & Brake, M. (Eds.) (1975). Radical Social Work. London: Edwin Arnold.

Banks, S. (2021). Ethics and Values in Social Work, 5th edition. London: Red Globe Press.

Barney, D. D., & Dalton, L. E. (2008). Social Work under Nazism, Journal of Progressive Human Services, 17, 2, 43-62.

Bauman, Z. (1989). Modernity and the Holocaust, Cambridge: Polity Press.

Benjamin, W. (1968). Illuminations. Essays and Reflections. New York: Schocken.

Biebricher, M. (2017). Progressive Jugendwohlfahrt als Motiv? Widerständiges Handeln im Umfeld des Jugendamts Berlin-Prenzlauer Berg als Beispiel für sozialdemokratisch-sozialistischen Widerstand in und aus der Sozialen Arbeit. In R. C. Amthor (Es.), Soziale Arbeit im Wiederstand! Fragen, Erkenntnisse und Reflexionen zum Nationalsozialismus (pp. 98-118). Weinheim: Beltz Juventa.

Bourdieu, P. (1977). Outline of a Theory of Practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Budde, W., Früchtel, F., & Hinte, W. (Eds.) (2006). Sozialraumorientierung. Wege zu einer veränderten Praxis. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Bussiek, B. (2003). Hertha Kraus. Quaker spirit and competence. Impulses for professional social work in Germany and the United States. In S. Hering, & B. Waaldijk (Eds.), History of Social Work in Europe (1900-1960). Female pioneers and their influence on the development of international social organizations (pp.53-64). Opladen: Leske + Budrich.

Charlesworth, L. (2010). Welfare’s Forgotten Past, Abingdon: Routledge.

Chief Secretary to the Treasury (2003). Every Child Matters, available at https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/272064/5860.pdf, (accessed 12/12 18).

Davey, J., Ashencaen Crabtree, S., & Parker, J. (2014). Researching indigenous cultures: Kinship as a form of Ubuntu. In S. A. Crabtree (Ed.), Diversity and the Processes of Marginalization: Reflections on Social Work in Europe, London: Whiting and Birch.

Day, P. R. (1979). Care and control: A social work dilemma, Social Policy and Administration, 13, 3, 206-209.

de Sousa Santos, B. (2016). Epistemologies of the South. Justice against epistemicide. London: Routledge.

Dollinger, B. (2006). Die Pädagogik der Sozialen Frage. (Sozial-)Pädagogische Theorie vom Beginn des 19. Jahrhunderts bis zum Ende der Weimarer Republik. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Dominelli, L. (2012). Green social work. From environmental crises to environmental justice. Cambridge: Polity.

Engelke, E., Borrmann, S., & Spatscheck, C. (2018). Theorien der Sozialen Arbeit. Eine Einführung. 7th ed. Freiburg im Breisgau: Lambertus-Verlag.

Erath, P. (2006). Sozialarbeitswissenschaft. Eine Einführung. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer.

Esping-Andersen, G. (1990). The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism, Cambridge: Polity Press.

Finkel, A. (2018). Compassion: A global history of social policy, London: Macmillan International.

Foucault, M. (1991). Discipline and Punish: the birth of a prison. London, Penguin.

Frampton, M. (2019). European and international social work. Ein Lehrbuch. Weinheim: Beltz Juventa.

Gaventa, J. (2003). Power after Lukes: A review of the literature, Brighton: Institute of Development Studies.

Giddens, A. (1984). The Constitution of Society. Cambridge: Polity.

Gilligan, C. (2016). In a Different Voice: Psychological Theory and Women's Development. Harvard: Harvard University Press.

Giroux, H. A. (2011). In the twilight of the social state. Rethinking Walter Benjamin’s angel of history. Truth Out. Available at https://truthout.org/articles/in-the-twilight-of-the-social-state-rethinking-walter-benjamins-angel-of-history/, (accessed 31.12.2020).

Grey, M., Coates, J., Yellow Bird, M., & Hetherington, T. (Eds.) (2013). Decolonizing Social Work. Farnham: Ashgate.

Harris, B. (2004). The Origins of the British Welfare State. Society, state and social welfare in England and Wales, 1800-1945. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Hering, S., & Waaldijk, B. (2006). Guardians of the poor, custodians of the public. Welfare history in Eastern Europe, 1900-1960. Opladen: Barbara Budrich Publishers.

Hering, S., & Münchmeier, R. (2014). Geschichte der Sozialen Arbeit. Eine Einführung. 5th ed. Weinheim: Beltz Juventa.

Ife, J. (1997). Rethinking Social Work: Towards critical practice, Melbourne: Pearson Longman.

IFSW/IASSW (International Federation of Social Workers/ International Association of Schools of Social Work) (2014). Global Definition of Social Work. http://ifsw.org/get-involved/global-definition-of-social-work/, (accessed 6/6/16).

Johnson, S., & Moorhead, B. (2011). Social eugenics practices with children in Hitler’s Nazi Germany and the role of social work: Lessons for current practice. Journal of Social Work Value and Ethics, 8, 1, http://www.socialworker.com/jswve (accessed 20/5/16).

Jones, O. (2020). Chavs: The demonization of the working class, 2nd edition. London: Verso.

Kuhlmann, C. (2000). Alice Salomon. Ihre Lebenswerk als Beitrag zur Entwicklung der Theorie und Praxis Sozialer Arbeit. Weinheim: Deutscher Studien Verlag.

Kuhlmann, C. (2007). Alice Salomon und der Beginn sozialer Berufsausbildung. Eine Biographie. Stuttgart: Ibidem.

Kuhlmann, C. (2008). Geschichte Sozialer Arbeit I. Studienbuch. Schwalbach: Wochenschau.

Kuhlmann, C. (2017). Soziale Arbeit im nationalsozialistischen Herrschaftssystem. Zur Notwendigkeit von Widerstand gegen menschenverachtende Zwangsmaßnahmen im Bereich der „Volkspflege“. In R. C. Amthor (Ed.), Soziale Arbeit im Wiederstand! Fragen, Erkenntnisse und Reflexionen zum Nationalsozialismus (pp. 40-57). Weinheim: Beltz Juventa.

Kunstreich, T. (2003). Social welfare in Nazi Germany: selection and exclusion, Journal of Progressive Human Services, 14, 2, 23-52.

Lachmann, R. (2013). What is Historical Sociology? Cambridge: Polity.

Lambers, H. (2018). Theorien der Sozialen Arbeit. Ein Kompendium und Vergleich. 4th ed. Opladen: Verlag Barbara Budrich.

Lambers, H. (2018). Geschichte der Sozialen Arbeit. Wie aus Helfen Soziale Arbeit wurde. 2nd ed. Bad Heilbrunn: Verlag Julius Klinkhardt.

Lepalczyk, I, & Marynowicz-Hetka, E. (2003). Helena Radlinska. A portrait of the person, researcher, teacher and social activist. In S. Hering, & B. Waaldijk (Eds.), History of social work in Europe (1900-1960). Female pioneers and their influence on the development of international social organizations (pp. 71-78). Opladen: Leske + Budrich.

Ling, H. K. (2007). Indigenising Social Work: Research and practice in Sarawak, Kuala Lumpur: SIRD.

Lorenz, W. (1994). Social Work on a Changing Europe, London: Routledge.

McKendrick, D., & Finch, J. (2017). ‘Under heavy manners?’ Social work, radicalisation, troubled families and non-linear war, British Journal of Social Work, 47, 2, 308-324.

Midgley, J. (1981). Professional Imperialism: Social Work in the Third World, Portsmouth, New Hampshire: Heinemann.

Müller, C. W. (2013). Wie Helfen zum Beruf wurde. Eine Methodengeschichte der Sozialen Arbeit. 6th ed. Weinheim: Beltz Juventa

Oakley, A. (2019). Women, Peace and Welfare. A suppressed history of social reform, 1880-1920. Bristol: Policy.

O’Hara, M. (2020). The Shame Game: Overturning the Toxic Poverty Narrative, Bristol: Policy Press.

Otto, H. U., & Sünker, H. (Eds.) (1986). Soziale Arbeit und Faschismus. Bielefeld: KT-Verlag.

Otto, H. U., Polutta, A., & Ziegler, H. (Eds.) (2009). Evidence-based practice. Modernising the knowledge base of social work? Opladen: Barbara Budrich Publishers.

Otto, H. U., Polutta, A., & Ziegler, H. (Eds.) (2010). What works. Welches Wissen braucht die Soziale Arbeit? Zum Konzept evidenzbasierter Praxis. Opladen: Barbara Budrich Publishers

Parker, J. (2007). Social work, disadvantage by association and anti-oppressive practice. In P. Burke, & J. Parker (Eds.), Social Work and Disadvantage: Addressing the roots of stigma through association, (pp.146-157). London: Jessica Kingsley.

Parker, J. (2018). Social work, precarity and sacrifice as radical action for hope. International Journal of Social Work and Human Services Practice. 6, 2, 46-55.

Parker, J. (2020a). Risks and benefits of convergences in social work education: a post-colonial analysis of Malaysia and the UK. In S.M. Sajid, R. Baikady, C. Shengli, & H. Sakaguchi (Eds.), Palgrave Handbook of Global Social Work Education, New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Parker, J. (2020b). The establishment (and disestablishment) of social work in Britain: The ambivalence of public recognition. Journal of Comparative Social Work. 15, 1, 108-130.

Parker, J., & Crabtree, S. A. (2018). Social Work with Disadvantaged and Marginalised People, London: Sage.

Payne, M. (2005). The Origins of Social Work. Continuity and change. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Peukert, D. J. K. (1987). Inside Nazi Germany: Conformity, opposition and racism in everyday life, New Haven: Yale University Press.

Piven, F. F., & Cloward, R. (1993). Regulating the Poor: The functions of public welfare, 3rd edition. New York: Vintage Books.

Prasad, M. (2006). The politics of free markets. The rise of neoliberal economic policies in Britain, France, Germany, and the United States. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Rathmayr, B. (2014). Armut und Fürsorge. Einführung in die Geschichte der Sozialen Arbeit von der Antike bis zur Gegenwart. Opladen: Verlag Barbara Budrich.

Richmond, M. (1917). Social diagnosis. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Sagebiel, J., & Amthor, R. C. (2017). Zum Widerstand in der Sozialen Arbeit in Europa. Spurensuche in den Gebieten unter deutscher Besatzung am Beispiel der Rettung jüdischer Kinder und Jugendlicher. In R. C. Amthor (Ed.), Soziale Arbeit im Wiederstand! Fragen, Erkenntnisse und Reflexionen zum Nationalsozialismus (pp. 249-271). Weinheim: Beltz Juventa.

Samuel, M. (2020). Social care leaders condemn Boris Johnson for ‘blaming’ care homes for Covid spread, Community Care, https://www.communitycare.co.uk/2020/07/07/social-care-leaders-condemn-boris-johnson-blaming-care-homes-covid-spread/ (accessed 07/07/2020).

Schilde, K., & Schulte, D. (Eds.) (2005). Need and care. Glimpses into the beginnings of Eastern Europe’s professional welfare. Opladen: Barbara Budrich Publishers.

Sylvester, O., Garcia, A., Crabtree, S. A., Man, Z., & Parker, J. (2020). Applying an indigenous methodology to a north-south, cross-cultural collaboration: successes and remaining challenges. AlterNative. DOI: 10.1177/1177180120903500.

Terpstra, N. (2004). Showing the poor a good time: caring for body and spirit in Bologna’s civic charities, Journal of Religious History, 28, 1, 19-34.

Tilly, C. (1981). As Sociology Meets History. London: Academic Press.

Tilly, C. (1978). From Mobilization to Revolution. Reading, Ma: Addison-Wesley.

Turner, A. (2019). Serious case reviews into toddler murders highlight social work staffing and oversight failures, Community Care, https://www.communitycare.co.uk/2019/06/06/serious-case-reviews-toddler-murders-highlight-social-work-staffing-oversight-failures/ (accessed 05/05/20).

Wieler, J. (2008). Brief Note: Remembering Irena Sendler: A Mother Courage honoured as most distinguished social worker of IFSW, International Social Work, 51, 6, 835-840.

Author´s

Address:

Prof. Dr. Jonathan Parker

Bournemouth University, Department of Social Sciences and Social Work

Fern Barrow

Poole

BH12 5BB, UK

parkerj@bournemouth.ac.uk

Author´s

Address:

Magnus Frampton

Universität Vechta

Fakultät 1 (Education and Applied Social Sciences)

Driverstraße 22

49377 Vechta, Germany

magnus.frampton@uni-vechta.de