Child protection in Germany and Russia from a practitioner’s point of view: Preliminary findings from an international comparative research project

Michael Herschelmann, University of Applied Sciences Emden/Leer

Nataliya Komarova, Moscow Region State University

Tatiana Suslova, Moscow Region State University

Albina Nesterova, Moscow Region State University

Pia Fischer, University of Applied Sciences Emden/Leer

1 Introduction

All over the world, violence against children is a severe problem. A UNICEF study shows that in the 28 countries examined, three quarters of children between the ages of 2-4 were regularly subjected to corporal punishment and psychological violence (cf. UNICEF 2017: 7). A quarter of children below the age of 5 grow up in domestic violence situations (ibid.). The authors conclude that: “Violence is both common and widespread – and no society is without some level of violence against its youngest members” (ibid.). In a survey of the WHO conducted in 133 countries, one in four adults stated to have been physically abused as a child; 36% said that they had been emotionally abused (cf. WHO 2014: 70), and 20% of women and 5-10% of men reported to have been sexually abused as a child (ibid.).

Almost all countries have established child protection systems to protect children from these dangers (cf. e.g. WHO 2014: 24 et seq., OECD 2011: 257). How these systems are established, their setup, structure and philosophy differ materially depending on social, cultural, legal and professional developments (ibid.). Despite this, the OECD report “Doing Better for Families” found that: “Child maltreatment has received less attention than other aspects of child well-being in international comparisons” (OECD 2011: 245).

German-speaking countries in particular suffer from a lack of comparative studies on the systems and practice of social work in different countries and regions (cf. Thole 2016: 19). Such studies, however, hold the potential of allowing researchers to:

· discover deficiencies in the principles of action and assumptions guiding a certain system, which only become apparent by comparing these with other ideas and systems;

· challenge patterns of behaviour and principles;

· learn from different experiences, thus making an important contribution to the improvement of the protection of children and adolescents (cf. Witte et al. 2017: 48).

These are also the objectives of the international comparative practice study on child protection in Germany and Russia presented ere by the University of Applied Sciences Emden/Leer (Germany) and Moscow Region State University (Russia).

2 Background

The last two decades have seen a number of international comparative studies being conducted and completed all over the world (cf. e.g. Merkel-Holguin/Fluke/Krugman 2019, Witte et al. 2017, Hong 2016, Spratt et al. 2015/Schweizerischer Fonds für Kinderschutzprojekte 2012, WHO 2014, Nobody's Children Foundation 2013, 2010, 2009, Nederlands Jeugdinstituut 2012, Kojan and Lonne 2012, Gilbert et al. 2011, Kelly et al. 2011, Munroand Manful 2010, Sajkowska 2007, Hetherington 2006, 2002, 1997, Freymond and Cameron 2006, Sicher et al. 2000). Though laudable, these show significant deficits in terms of both content and geography. Kindler (2010) points out that “apart from a few exceptions (e.g. Sicher et al. 2000; Sajkowska 2007), especially East and Southern Europe remain invisible” (Kindler 2010: 13). One striking omission is that Russia did not feature in almost any of these studies (with the exception of Sicher et al. 2000, WHO 2014: 182), which leads to very little being known in Germany about the child protection system and social work in Russia in general (cf. e.g. Berrien et al. 1995, Johnson et al. 2014, Burkova 2006, 2007a, 2007b, Krieger 2015).

2.1 Child abuse in Germany and Russia

Violence against children continues to be a prevailing societal problem in both Germany and Russia. In 2018, 136 children died as a result of domestic violence in Germany. Almost 80 percent of them were younger than six years of age at the time of their death. The crime statistics for 2018 of the German Federal Police also quote 14,606 known cases of sexual abuse of children pursuant to Section. 176, 176a and 176b of the German Criminal Code (StGB) (Deutsche Kinderhilfe 2019), though the estimated number of unknown cases is significantly higher. A representative study for Germany (Fegert 2017) has shown that 6.5% of the people interviewed reported severe emotional abuse in their childhood and adolescence, 6.7% reported severe physical abuse and 7.5% reported severe sexual abuse. 22.5% of the people interviewed told of severe physical neglect in their childhood and adolescence. In 2017, youth welfare offices in Germany initiated around 143,300 risk assessments regarding the well-being of children, 45,700 cases of which were found to indeed pose a threat to a child’s well-being in 2018 (cf. Statistisches Bundesamt 2018).

In Russia, the problem of child abuse in families is becoming increasingly apparent and discussed, and is the most acute social, medical-social and psychosocial problem Russian society is facing. The separation of domestic violence into its own independent, distinct social problem occurred in early 1993. The impetus for initiating the public debate and the academic research regarding this problem came from public women's organisations and specialists in the field of psychology and sociology. Emphasising the importance of this burgeoning field of research, sociologists have reported that around 40% of serious violent crimes were being committed in the family (the victims were not only children, cf. Nesterova 2018). Scientists and practitioners also found that violence, alcoholism and drug addiction have become the far too commonplace in crisis families, and that action must be taken (ibid.).

Every year in Russia, up to two million children and adolescents are subjected to violence in its various forms; about one million children aged 4-14 are beaten by their parents, more than 50,000 of them run away from home every year, fleeing from the beatings of parents and other older relatives (Spirina and Spirina 2012).

According to the results of a study conducted by A. G. Gritsay and V. I. Spirina in preschool educational institutions in the city of Armavir in the Russian Federation, violation of the rights of children are most often associated with degrading the child and causing them physical harm; this may include physical punishment (25.0%), verbal abuse (15.0%), threats (35.0%), deprivation of pleasure (25.0%) (cf. Gritsayand Spirina 2011), whereby "deprivation of pleasure" is understood as, for example depriving a child of permission to go outside, sweets, permission to watch television, etc. Both Russia and Germany have legal provisions, institutions and procedures in place for combatting the societal issue of violence against children. While Germany has had these in place for quite some time, it was only in the last few years that Russia began establishing such mechanisms. The question now is how can such different systems be compared in a way that allows deriving logical and helpful conclusions.

2.2 International comparative research

In addition to the development of theoretical conceptual frameworks for an international comparison of child protection systems (cf. Kindler 2010, Müller 2010, Wulczyn et al. 2010), a number of specific comparisons were also made in recent years. The table in the annex provides an overview of the projects and empirical studies making an international comparison of child protection systems. These vary significantly in terms of the countries included, the selected topics and the applied methods:

One of the goals of these comparisons was the attempt to establish typologies of child protection systems. The most wide-spread typology is the differentiation between two fundamentally different functional orientations proposed by Gilbert (1997). He differentiates between the “child protection” orientation and the “family service” orientation based on the analysis of child protection policies and professional practice in nine countries (cf. ibid. in more detail). Hetherington et al (2006), who differentiate between a “dualistic child welfare system” and a “holistic welfare system” (cf. ibid.: 46 et seq.), proposes a similar dualistic system. Freymond and Cameron (2006) supplement the typology put forth by Gilbert by a third heuristic “generic system” and describe “community caring” as an orientation accommodating special features of indigenous groups like the Aborigines in Australia or the First Nations in Canada (cf. ibid.: 4 et seq.). To better reflect fundamental societal changes, Gilbert et al. (2011) added a third “child focus” orientation to the already existing typology in another analysis (cf. ibid.: 255). However, like all other authors, they found significant variations and an increasing complexity of child protection systems among the countries and in their development, which no longer allow for easy categorisation in their current state. Instead, they assume a mix of orientations in different countries which are to be placed within a three-dimensional matrix (between child focus, family service and child protection) (cf. ibid.).

Many comparative studies highlight the necessity of considering cultural differences when assessing child abuse. For example Europeans or Americans are likely to see it as completely justified to allow a child to sleep alone in his or her own bed, while in some other cultures, for example, African cultures, to leave a child to sleep in a separate dark room is considered improper and cruel and a sign of a lack of affection. At the same time, for example, it is quite normal for Africans to use hard child labour for the welfare of the family, as this is an important part of the education of respect for their family; an emphasis on their duties. Many people in Africa and Asia also employ harsh physical discipline on children, as well as methods of treatment of children which would be interpreted in Europe as acts of violence (for example, burning ulcers with hot metal, beating with sticks, etc.).

The world health organisation reports a need for a cultural comparison of attitudes to abuse in different countries, as well as an analysis of the experience made in different countries regarding the protection of children from violence. For instance, it was noted that parents from Korea, Egypt, India and the Philippines confessed to the use of physical violence, beating their children for disciplinary purposes. In the Philippines, psychological violence against children is used as a common form of punishment; intimidation, threats to leave a child, abandonment, etc. (cf. WHO 2014).

Connoly and Katz (2019) criticise the typology proposed by Gilbert (1997) by claiming it is focused on experiences in high-income countries and lacks relevance for many parts of the world, particularly low-income countries where there are different challenges in protecting children and where there are minimal resources to invest in child protection infrastructure (cf. Connoly and Katz 2019: 383). Furthermore, Gilbert's conceptualisation focuses on the processes of assessment of risk and/or need and intervention to protect children by designated child protection workers and does not take into account the crucial role of health, education, justice, housing and other sectors (cf. ibid.). They suggest an international child protection system typology that has universal application and reflects two fundamental drivers of system orientation: the role of children in societies and the nature of service systems. This values and beliefs-based typology should allow placing child protection systems along a continuum in ways that are a) more or less individual or community oriented and b) more or less formally regulated (cf. ibid.).

Thus, it is worth noting the importance of taking the cultural factor in the definition of violence against children into account. This lack of cross-cultural studies of attitudes to violence against children as well as the lack of cross-cultural comparative analyses of the systems of protection of children from violence in Russia and Germany, are the gap which this study seeks to fill.

In summary, the objective of international comparisons should not be the categorisation of countries in specific typologies (and even less any comparisons of their performance) but it rather should be about learning from differences to determine the strengths and weaknesses of the respective approach and identifying alternative strategies (cf. Hetherington 2006).

3 Methodology

The basis for this analysis is the research methodology developed at the “Centre for Comparative Social Work Studies (CCSWS)” at the Brunel University London, which had been used in two major international comparative research projects (cf. Hetherington et al. 1997, Hetherington et al. 2002, Hetherington 2006 for more detail). It is a type of “action research,” using the perspective of practitioners as the empirical foundation in a qualitative “bottom-up” approach (cf. Hetherington et al. 2002: 12 et seq.), with the objective: “… to learn about the child protection system of the other country in terms of how it worked for those directly involved in operating it; and to elicit the views of social workers in one country about the practice and system of another” (Hetherington et al.1997: 43).

At the core of this methodology is a case vignette discussed by groups of practitioners in the respective countries to gain an insight into how the researchers’ own and the other country’s child protection systems work and to perform a joint comparison by experts. Hetherington (2006) summarises the approach as follows:

In each participating country, a group (or groups) of social workers and other relevant professionals was established. Each group heard the same story, which was developed over several stages. The group decided what would be most likely to happen to the family in their locality. This provided a picture of the system in action. The group then heard about the discussion and decisions made by a group in another country working on the same case material. They identified similarities and differences between the way the systems worked, as well as the anxieties and preoccupations of the social workers within these systems. In making these comparisons, they reflected on their own system, as well as on the other system. (p. 30).

Case vignettes are used both in international comparative research (cf. Hetherington et al. 2002: 13/14) and (in isolated cases) also in national research projects (cf. e.g. Kutscher 2010). Limitations and possibilities are discussed extensively in Hetherington et al. 1997: 50-55 and Hetherington et al. 2002: 19-23 (cf. also Mabbett and Boldersum 1999, Cooper 2000).

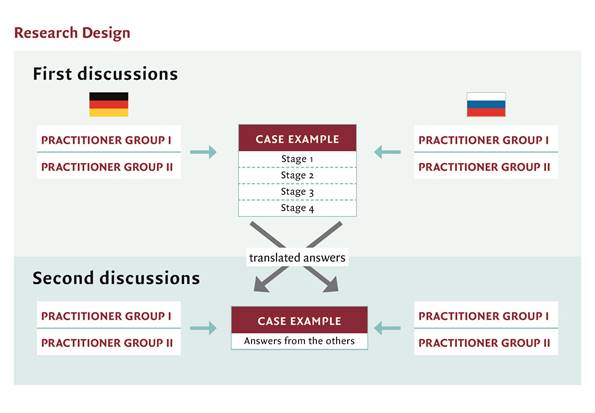

3.1 Research design

In a first meeting, questions about the case which developed in four stages were answered individually by the participants in writing (ibid.). In each stage, they were to answer: What would you do? Why would you do that? What are the legal restrictions and options? What is the theoretical or conceptional basis of your perspective? (ibid.). Subsequently, the case was then discussed with others in the group. The discussions were moderated by the research team making sure that the following topics would be considered in all groups:

· “the plans they might make with the family or its individual members;

· rights and responsibilities of the characters in the study;

· the roles and tasks of professionals (…);

· family and individual dynamics in the case;

· political and social factors which might influence thinking about the case; and

· organisational and institutional factors affecting their response to the case.” (Hetherington et al. 1997: 44)

The participation of specialists from institutions and organisations from the rural areas of Aurich and Moscow region in this study helped identify two additional indicators:

1. features of assistance to families and children in rural areas, in comparison with an urban environment;

2. the impact of distinctive features on the construction of a system of assistance to families and children in rural areas.

These are also the topics for the analysis of the content of the discussions, which were recorded and transcribed (Katz/Hetherington 2006).

In a second meeting, short descriptions of the respective other child protection system and the answers of the other practitioners were presented to the practitioners and then discussed; what is the same, what is different, interesting or unexpected (cf. Hetherington et al. 2002: 16). This is intended to encourage them to reflect on their own system since: “The participants in this second, reflective, stage were asking not only ‘why do they do it that way?’, but ‘why do we do it differently?’ They were questioning their taken-for-granted assumptions” (ibid.: 14). With this approach, four different types of data were generated:

1. a description of the functioning of the system prepared by experts,

2. information about the concerns of the people who work within this system,

3. the practitioners’ view of the differences and similarities between the systems

4. the views of the practitioners on these differences (cf. Hetherington 2006: 30 et seq)

The goal is not “to create hierarchies of good practice” (cf.

Hetherington et al. 2002: 16), nor does the study claim to be able to describe

what would happen in a statistically normal case or “on average” in a country

(cf. ibid.: 13). Rather, the study strives to understand and describe different

paths taken by practitioners in different countries for handling the same case,

these paths being possible within the parameters dictated by the structures and

the culture in a specific place at a specific time: “We are never saying ‘this

is how it always works in Italy’, or even ‘this is how it always works in north

east Italy’, but say ‘this is how, within the structures and culture of Italy,

it can work’” (ibid.: 21). Therefore, such work is rather the start of a common

understanding of the respective other system (cf. Hetherington et al. 1997: 50

et seq.), the opening up of a dialogue (cf. ibid.: 54).

3.2 Sample

The research methodology chosen for this study requires the group composition to include 6-8 participants, the composition of whom may vary depending on the roles and responsibilities. However, all participants should be working in child and welfare services in the same location (cf. Katz and Hetherington 2006: 431). Two groups of practitioners were chosen to provide the German perspective:

1st Group (N=8): 1 social worker working for the youth authority “Jugendamt” (general social service department “Allgemeiner Sozialer Dienst”)/ 1 social worker working for the youth authority “Jugendamt” (advice centre for families)/ 1 social worker working for the youth authority (service for foster children)/ 2 kindergarten teachers (one of whom in a management position)/ 1 social worker, working at a (special needs) school/ 1 teacher working at a (special needs) school/ 1 social worker working for a non-governmental youth welfare service (“Ambulante Erziehungshilfe” needs-based support for families, children and youths)

2nd Group (N=6): 2 social workers working for the youth authority (general social service)/ 1 kindergarten teacher (private)/ 1 social worker working for the local education authority/ 1 teacher working at a (special needs) school/ 1 psychologist working for a non-governmental youth welfare service (violence prevention hotline)

There were also two groups of practitioners from Russia:

1st Group (N=5): 3 kindergarten teachers/ 2 school teachers

2nd Group (N=3): 1 specialist working at the department for guardianship/ 1 director of an outpatient family counselling centre/ 1 specialist working for the Commission for Juvenile Affairs and Protection of Their Rights

The first group discussions were held in the period of March-August 2018, the second group discussions in the period of March-June 2019. As a further development, “service users”, i.e. parents and/or family members, were also included in this study in Germany as of June 2019; attempts to do this had failed in the past (cf. Hetherington et al. 2002: 17).

4 Preliminary findings

This section discusses selected statements of practitioners from Germany and Russia on the individual stages of the case study from the first discussion meetings (see the figure on the research design). The focus here is on the professionals from the responsible state institutions (in Germany the youth authority “Jugendamt” and in Russia the “District Commission for Juvenile Affairs and the Protection of Minors’ Rights”). The statements are first summarised in a purely descriptive manner to allow for an initial insight into how the participating practitioners would approach the case within the scope of their systems. A more detailed and theory-guided analysis will be performed at a later time.

4.1 Case example: Stage 1

Mrs Schmidt contacts the social services department. She says that she is worried about her daughter's marital problems. She is not specific about the nature of the marital problems. She also expresses concerns about the nature of the relationship between her son-in-law and her granddaughter, her daughter's child by a previous marriage. Her daughter's family comprises:

Father: Johannes age 40

Mother: Valerie age 33 (Mrs Schmidt‘s Daughter)

Daughter: Franziska age 13 (Mrs Schmidt‘s granddaughter, Johannes' step-daughter)

Son: André age 4 (Mrs Schmidt's grandson)

The family is not known to the social services department.

Germany: The professionals from the general social service department (“Allgemeiner Sozialer Dienst”) of the youth authority (“Jugendamt”) would first try to clarify the exact nature of the grandmother’s concerns? The social workers would ask her if she had discussed it with her daughter and what the latter thinks about it. Is the grandmother willing to disclose her concerns if she has not talked with her daughter about it?

Workers from the general social service department of the youth authority are not allowed to ring the family’s doorbell directly after only this one phone call providing them with rather unspecific information. In addition, the social workers are not allowed under any circumstances to obtain information from third parties (e.g. from the school).This means that the first thing that must happen, the only real thing that can happen at this point, is that the grandmother needs to speak with her daughter and encourage her to seek pedagogical consultation.

One other matter that the social workers are to clarify is whether the girl’s biological father is entitled to custody. If this is the case, they would be required to include him when talking about the girl and issues regarding the girl. For now, the stepfather does not have anything to do with the girl.

Based on the description of a bad relationship between the stepfather and the pubescent stepdaughter, the social workers would think along the lines of sexual abuse, but would initially handle this matter carefully. They deemed it a problem that even if the grandmother manages to get her daughter to ask for support from the youth authority , there are still no specifics as to how the youth authority can help; they cannot really intervene because there is nothing tangible to intervene in.

The general social service department of the youth authority would also need to determine their own responsibility (competent youth authority office? Social worker responsible for the district?), since it may also be a matter of financing assistance. At this point, the professional also explained that there is an additional problem: People calling in and reporting cases anonymously assume that the youth authority then has to come and do something and they also expect to be told what happened. However, this is not possible due to data protection law and also conflicts with the basic approach that a relationship must first be established with the persons concerned to really enable the social worker to provide assistance. They said they would refer the grandmother to various counselling options for the daughter (by a counselling centre or the youth authority itself) and offer that she come to the youth authority with her daughter (if the latter is willing to do so). Furthermore, as a first step, they would recommend to any person seeking advice to contact third-party counselling centres, since there is a prevailing image of the youth authority coming in and taking children away, both in the society in general and in some families, and parents are very afraid of this.

At the same time, however, they would also tell the grandmother that they are not allowed to inform her about the further course of this case due to privacy issues. The problem with this is that it very frequently causes the persons making the report to get the impression that the youth authority is not actually doing anything, just because they are not given any information about it.

If the parents make contact at this point, show awareness of problems and express a desire to receive support, the participating social workers said that they believe that some help in raising the children could be set up, specifically family assistance or a parenting counsellor for the older daughter.

If not, nothing else can be done at this stage for the time being. At most, the grandmother can be told that she may contact the youth authority on-call service via the emergency call centre outside of the office hours if fights and acute violence towards the children occur.

Russia: The employee from the “District Commission” explained that “all information of educational institutions and social centres about events of child abuse is reported to us in the Commission for Juvenile Affairs since we are the coordinating authority in the district”.

The employee went on to explain that it would be checked in a case like this why it is not the daughter but the grandmother who is raising the alarm because of the concerning relationship between her son-in-law and the granddaughter. In this regard, it is important that the grandmother talks to her daughter and tells her about her concerns regarding her granddaughter. Furthermore, the social worker also stressed that it may not be overlooked that the 4-year-old André is also growing up in the family. It is important to ensure the well-being and safety of this child as well.

However, if this is confirmed to be a case of child abuse (in the present case suspected molestation), the Commission will initiate proceedings to protect the child’s rights. After the decision about initiating proceedings against child abuse was made, a task group is established which includes professionals of the Help Centre for Families and Children or a welfare organisation. This task group usually consists of 3-4 persons (more is not possible for psychological and ethical reasons) and includes: 1) an employee of the Commission for Juvenile Affairs; 2) a representative of the authorities for social protection; 3) a representative of the guardianship office; and 4) (if needed) a police employee. once established, the task group determines the nature of the problem: If they problem is a psychological one, it calls in a psychologist, if it is a crime, it involves the police. The task group assesses the social risks for the child and prepares a rehabilitation schedule for the family and the child. All participants in the discussion expressed the view that work with the family where child abuse is discovered should be carried out with the family as a whole. It would be counterproductive to only consider the child concerning whom the Commissions on juvenile Affairs was contacted. Helping the child rather requires observing and monitoring the dynamics of family members and, in case of a deterioration of the situation, to take measures. This work is performed in co-operation with a social medical psychological-pedagogical council which exists in each city district, the educational organisation the child attends and the organisation for social protection of the population. While working with the family and rehabilitating the child, the dynamics of the changes in the child’s living conditions are monitored continuously. This is performed in line with the severity of the case, either daily or weekly. The results of the monitoring are then used to make corrections to the social workers’ activities to ensure an effective influence on the family and providing psychological, social, medical and other support to the family and the child. When the task group becomes aware that the child is no longer threatened, it will decide whether to terminate the proceedings against violence and child abuse. However, in most cases, the decision is made to appeal to the court for revocation of custody rights and to the guardianship office to find a guardian or adoptive parents.

4.2 Case example: Stage 2

Valerie and Johannes have refused to see the social worker so there is no further contact with the family until one month later, when the worker at the playgroup attended by André contacts the social services department because she is concerned about him. She says that his attendance at the playgroup is irregular, that he is excessively violent towards the other children and that his mother seems depressed.

Germany: The kindergarten workers would first prepare a risk assessment based on these observations in their team. This, at first glance, would not be deemed something that would necessarily constitute a reason to contact the youth authority in their opinion. Rather, this is their daily routine (that children come irregularly, that children hit each other, that mothers behave a bit strange); they are not real, serious indications giving rise to a suspicion that the child’s well-being is at risk. They would, however, document everything in detail from that time on.

The kindergarten workers would try to have a very tactful, non-confrontational talk with the mother and the son (separately) to find out the reasons for non-attendance and the mother’s perceived depression. If the relationship is not good, great care must be taken.

If more specific information is available and if the kindergarten workers have been exchanging their views with one another, they are obligated to follow a procedure pursuant to Section 8 of the eighth volume of the German Social Code (SGB VIII). Accordingly, they would be expected to consult a professional experienced in these matters and then return to the kindergarten with new insights. They would then seek a dialogue with the parents, and if they are successful, they can gain the parents’ goodwill, and a successful co-operation can be established. In the worst case, they could lose the parents’ trust due to them getting a feeling of being ambushed and remove the child from the kindergarten.

The social workers of the general social service department of the youth authority confirm that the observations are not specific enough at this point and that they will give appropriate feedback to the kindergarten. Kindergarten attendance is not mandatory, and the children “hitting” one another may also just be a trial of strength among the kids; this does not constitute a threat to the child’s well-being. Calling the youth authority would be excessive, too early and too unspecific. They also experience cases in which children are taken from the kindergarten if the kindergarten has contacted the youth authority.

Russia: A kindergarten teacher said that she would “first find out what had happened to André and what kind of help he needs, carefully and without violating his personal boundaries”. She would then explain to the other children that they should not treat him badly because all children of the group are very good and warm-hearted and should support each other. She would observe in which situations André gets more aggressive and would try to defuse the aggression. Secondly, at the same time as working with André, she would try to talk with his mother. Involving a psychologist in working with the mother is also an option.

Another kindergarten teacher shared her colleague’s opinion and stressed that “it would be necessary in any case to clarify with the mother what she has done to resolve this situation, which kind of help she believes to be necessary and how the kindergarten and I as the kindergarten teacher can help. As the kindergarten teacher, I can prepare the necessary documents to send the child (André) away for treatment for stabilising his health. The child could spend the time at the health facility with his mother. In addition, it is necessary to determine the situation in the family; the results would allow us to plan measures to support the child and the family. If the situation in the family poses a threat for the child, the Commission must be contacted. If we think we can handle the situation on our own, we will do so”.

In the opinion of the Commission employees, the kindergarten teacher must report it to the kindergarten director if she notices a problem with a child (with André). The kindergarten director must pass on this information (about suspected child abuse) to the office for education. The director of the office for education must pass on this information to the Commission for Juvenile Affairs. They are all part of a well-developed system. If a child (André) is frequently absent from the kindergarten, the Commission for Juvenile Affairs as the co-ordinating authority is required to inquire with the health care authorities (with the paediatrician regarding the child’s – André’s – health). A social worker will also visit the family and review the child’s living conditions. In particular, the specialist stressed that “all directions and decisions of the Commission for Juvenile Affairs and the Protection of Minors‘ Rights are binding for all subjects of the preventative system for early detection of cases of breaches of children’s rights”.

4.3 Case example: Stage 3

Two weeks later, the social worker has seen Valerie once, but did not get much information from her. Franziska’s teacher contacts the social services department. Franziska has asked her teacher if she can talk with a social worker. She has run away from home for three days and has just returned. She complains of violence between her parents. She also expresses a concern that her relationship with her step-father is more intimate than she would like it to be, but she will not say more about it.

Germany: The worker of the general social service department of the youth authority assumes that the child means she wishes to talk to social worker from the youth authority. Since the child concerned very clearly expressed her desire to talk to the social worker, the school may call them, as this is child’s right. Usually, this takes place via the guidance counsellor or the school’s principal. This would actually be something they do regularly, and they would then drive to the school since this is a safe space and it would be difficult for the children or adolescents to come to them in the afternoon and to manage both the distance and their embarrassment. They would usually set this in motion in 15-20 minutes and then have a talk, in most cases in the presence of the guidance counsellor or another trusted third party, to hear what the girl wants to talk about and to provide information about her legal situation and her options. In case of doubt, it is not even necessary for the girl to say in detail what her stepfather is doing; rather, it is sufficient that there is violence in her home and she does not feel safe there. The social worker then has the authority to find a place to stay for the girl for the time being, regardless of whether the parents agree to this or not.

The purpose of talking with the girl is to give her the opportunity to get something off her chest and to provide her with security and a safe space. The girl is legally entitled to removal from her home at her own wish, also independently of age limits. However, it requires contacting and including the biological parents (not the stepfather). They must be informed about the facts and agree to the removal from her home. If they object to it, the social worker has no choice but to contact the court. At the same time, the younger brother must also be considered.

The specialist from the counselling centre who has experience in this regard notes that teachers can seek anonymised counselling in cases of acute danger to a child’s well-being pursuant to Section 4 of the German Act on Co-operation and Information in Child Protection (KKG) and may also provide the name in this case. They also made it clear that in case of a removal of the child from the home, the employees of the youth authority may not discuss certain things with the school without a release from confidentiality by the parents. However, if this is discussed with the parents beforehand, 90% agree to this. Another option for the social worker to consider is the girl discussing the issue with a specially trained professional in a counselling centre for sexual abuse if she wants to.

For the other workers of the general social service department of the youth authority a risk assessment would be made within the team at this point the latest. Not only for the girl but also her younger brother. Depending on the results of the assessment, they would also notify the family court. The parents would need to agree to a removal of the girl from her home. If they do not, the social worker must inform the court of this within 24 hours. In light of the collected information and experience, the family court should be informed. This enables the family court to take measures for the protection of the children if are unwilling or unable to step up their cooperation, e.g. the removal of the younger brother from the home as well to remove the children from the danger zone for the time being and then establish what is actually going on in the family as a follow-up. At this time the latest, the social worker would inform the parents that they are responsible for protecting the child’s welfare and advise them that someone else will make the decision for them if they do not accept the help offered and if the family court is informed of this. However, the predicament is that their position is not always the crucial factor for the judges’ decisions. It is not a rare experience that children and adolescents were in situations in which it was clear to them that the child’s well-being was in danger and it was actually clear from the beginning that the parents will not accept non-institutional help. Nevertheless, the judges decided that the children should be returned to the family, non-institutional help should be established, and the further development of the situation should be monitored. As social workers, they would frequently take the position that a limit has been reached for the protection of the child’s well-being, and a removal from the home and clearing is required, i.e. a period in which it is clarified what is actually going on, what the family needs to allow the children to return home. The children are moved to emergency foster care or a clearing residential group, and, together with the parents, they work out what this familial system needs in order to become functional again and to allow everyone to live together well so that the child may develop positively. However, the judges then say that this is not sufficient yet and send the children back to their families.

Russia: The Commission’s specialist makes it clear that the school is obligated to report this case to the Commission. The unified on-call service for the Moscow region can be contacted using the phone number 112. This phone number gathers all incoming calls about difficult situations, including a child running away from home. The parents whose child has run away from home may also call this phone number. The employees of the Commission for Juvenile Affairs working with families in the risk group stress towards the parents that the parents should not be apathetic and irresponsible and that they should immediately call the phone number 112 when needed – if a child has disappeared. The call to the unified on-call service is then forwarded to the Commission for Juvenile Affairs. In addition, the Commission reviews educational institutes 4 times a year to identify the children belonging to the following groups: 1) children in difficult living conditions; 2) children in a socially dangerous situation (like Franziska); 3) children in families in which the parents do not fulfil their parenting obligations (in which the situation is not critical for the time being but there is a risk of child abuse). This means that such a case would definitely become known to the Commission in some way, even if neither of the parents, the grandmother or the child themselves had reached out for help.

Franziska’s case is, socially speaking, a dangerous situation. According to the provisions of the Gouverneur of the Moscow No. 101 territory “On working with families in a dangerous situation”, the child (Franziska) is offered a room in the social district rehabilitation centre for minors if the employee of the Commission for Juvenile Affairs and the Protection of Minors’ Rights sees that the information is correct. The child can be placed in the centre upon request by the parents or the child themselves. Such removal is to be considered an urgent social measure (e.g. a child is immediately admitted at night, solely based on the child’s statement, a refusal is not possible – there is no time to form a task group). They can only take the child away from the family and into their care with a representative of a law enforcement agency, and failure to do so would be a violation of the rights of the family. However, the social worker has the right to visit the family and assess the child's living, economic and psychosocial conditions.

4.4 Case example: Stage 4

In the course of discussions with the social worker, Franziska decides that she wishes to stay at home but that she wishes to continue to have help from the social worker. Eight days later, the playgroup worker contacts the social services department again. She says that André is increasingly violent and distressed. The worker has suggested that Valerie should take him to the doctor, but she has refused. The worker is worried about André. Franziska says that the domestic violence is continuing, but that her mother does not wish to leave home. Franziska says no more about her relationship with her step-father.

Germany: For one of the social workers of the general social service department of the youth authority this is now an unambiguous situation that requires talking to the mother one last time and then informing the family court. They have received additional information that the situation is becoming worse and coming to a head and that the person having custody of the children is not willing to change anything. They would invite the mother one more time to drive home how serious the situation is and to stir her from the inaction to which she has resigned herself, either because she is too weak, or because she does not want to take action. They would tell her clearly that she is obligated to protect her children if she becomes aware that the other parent is a danger to them. In case of doubt, the issue of a restraining order against the stepfather within the scope of proceedings for protection from violence should be explored.

At this stage, it becomes a case for the courts, regardless of what will be decided. There will be a hearing and the possibility that the mother will co-operate then. It is now a situation in which nothing more can be achieved by goodwill; after all, this option has been exhausted.

Another professional of the general social service department of the youth authority said they would “talk up” family assistance, a short-term crisis intervention with a relatively high number of hours to the parents, reminding them that they do not have much choice anymore. If necessary, they would set up a parenting counsellor for the girl. And if the parents do not co-operate, they would inform the court of this in any case, obtain the order for removal from the family and initiate a clearing, also to ease the burden on the mother.

Russia: The practitioners considered it vital that André see a psychologist to work on his behavioural problems and his psycho-emotional condition. This also means that the employees of the Commission for Juvenile Affairs and the Protection of Minors’ Rights need to call in a psychologist into the task group when working with André (they may e.g. use the fairy tale therapy method for diagnosis). Every kindergarten has a medical specialist (who is to examine the child) and a psychologist (diagnosis, working with André and supporting him) who can help with the process. For their part, social and psychological centres also have independent psychologists available (help for Franziska, for the mother and the whole family). All these tasks are carried out under the supervision of the Commission.

5 Conclusion

The analysis of the group discussions held between the various practitioners has revealed both commonalities as well as differences in the ways in which different systems attempt to resolve the problem of violence against children.

Commonalities:

1. Violence against children is a relevant and prevalent problem in both Germany and Russia, and both countries exhibit a large number of cases involving abuse of underaged children.

2. Both countries have clear procedures regulated by law for working with families in which child abuse has been diagnosed. A system has been put into place which is designed to help both children and the family as a whole to deescalate and mitigate cases of domestic violence.

3. There is a great level of awareness on the topic of the prevention of violence against children.

4. Practitioners are trained and educated throughout their career to allow them to provide the best possible assistance to children in critical situations.

5. Both countries are developing social-pedagogic and psychological methodologies for intervening in crisis situations and for providing systematic support.

6. Various organisations are working together in order to form networks for supporting children who suffer from violence.

7. In Germany, NGOs and other non-governmental information and counselling centres have been working with children who have fallen victim to violence for quite some time now. In Russia, the last decade has seen several public foundations taking on a similar role in the fight against this problem.

Differences:

1. Germany has several decades of history of dealing with child protection, whereas Russia started its systematic social work with children and families in case of abuse later (since 1991). It is for this reason that most decisions regarding cases of violence against children are made by the guardianship offices and the Commission for Juvenile Affairs and Protection of Their Rights , which are the remit of the local authorities. It is only in the last two decades that social organisations were allowed to play a real role in the rehabilitation of victims of violence.

2. The case responsibility in Germany lies with individual experts from the youth authority (in cooperation with others) while in Russia there is a multi-professional group convened by the Commission for Juvenile Affairs and Protection of Their Rights.

3. In Germany, schools, kindergartens and similar institutions are obliged to actively seek out signs of child abuse, to speak with children, parents, work to provide help and (only then!) report the matter to the proper authorities. In Russia, teachers and educators provide independent assistance and support to children suffering from a negative psycho-emotional living situation caused by domestic violence. Nevertheless, should they come to the conclusion that the living situation with the family constitutes a real and present danger to the life and well-being of the child, they are obliged to report this to the Commission for Juvenile Affairs and Protection of Their Rights and to help protect the child’s rights.

4. Kindergartens in Germany work in cooperation with external medical and psychological staff. In Russia, Kindergartens have their own medical and psychological staff (but also cooperate with external staff).

5. In Russia, the child’s health and psychological well-being is examined and diagnosed with the participation of a medical-psychological-pedagogical commission; Germany has no such practice.

6. In Germany, the youth authority works with schools and kindergartens in a case-related manner, whereas in Russia the “Commission” screens schools and kindergartens four times a year to locate children in difficult situations, socially endangered children and children at risk.

7. Russian parents are likely to view police officers as a person of trust, while in Germany this is not the case.

8. There is a large variety of artistic contests in Russia to support victims of child abuse; Germany only has a few of those. On the contrary, Germany has more initiatives in place which work with fathers in cases where, for example, the child has been taken away from the family following a reported case of abuse, while Russia has fewer offers of this nature.

These are only preliminary results and must be analysed in depth.

6 Limitations of the approach

The following restrictions must be considered in this kind of analysis: There are many gaps in information and understanding in relation to the studied countries, and this work is provisional and merely provides a beginning to understanding other systems (cf. Hetherington et al. 1997: 55/51). Furthermore, the groups of social workers examined in each country were quite small, and may not be representative of their peers, thus making generalisations difficult (cf. ibid.). But it is to emphasise that in this approach

“we do not seek to make generalisations about ‘what Belgian (or German or etc) social workers think’ or ‘what English social workers think (or do)’. What we have is a series of pictures. These pictures show us how a certain set of events might be handled in different countries, and what the thinking behind the action would be; they show us that picture and they show us a reflection of that picture through the eyes of a group of social workers in another country” (ibid.).

Aside from the complexity of both child protection systems and the different cultural backgrounds, the language barriers make it difficult to reach a mutual understanding. Language and the understanding of problems differ between countries and there can be false similarities in which things appear equivalent that are not (cf. Hetherington et al. 2002: 19). There could be variations in the underlying meaning of words which might appear to translate easily (cf. ibid.: 20). In some cases, different terms exist for the same issue, and the necessary written translations can sometimes be misunderstood, unclear or ambiguous. It is therefore important to be aware of the potential ambiguities and uncertainties of language and conceptualisations at every stage of the work and to allow time for discussing and resolving uncertainties in understanding (cf. ibid.). Actual understanding can frequently be achieved by personal dialogue only. There are also differences in the conventions and traditions of academic research between western and eastern Europe which could potentially lead to a breakdown of communication or difficulties in understanding one another (cf. Breitkopf and Vassileva 2015). In addition, the groups‘ compositions in Germany and Russia are slightly different. Despite these difficulties, valuable initial insights into the different child protection systems could be obtained. They must be explored further in future research and be analysed with regard to self-reflecting insights regarding the researchers’ own system obtained in the second round of discussions.

References

Berrien, F., Aprelkov, G., Ivanova, T., Zhmurov, V., & Buzhicheeva, V. (1995). Child Abuse Prevalence in Russian Urban Population: A Preliminary Report. Child Abuse & Neglect, Vol. 19, No. 2, pp. 261-264, 1995

Breitkopf, A. & Vassileva, I. (2015): Osteuropäischer Wissenschaftsstil. In P. Auer, & H. Baßler (Eds.) Reden und Schreiben in der Wissenschaft. Frankfurt; New York: Campus Verlag

Burkova, O. (2006). Entwicklung einer Infrastruktur sozialer Dienstleistungen zur Bewältigung von Belastungen und Problemen von Kindern und Jugendlichen in der Russischen Föderation. Berlin; Münster: Lit.

Burkova, O. (2007a). Die Ausbildung für soziale Berufe. Russische Föderation. SozialExtra. Jg. 31. H. 3/4, pp. 55-57

Burkova, O. (2007b). Kinder- und Jugendhilfe in der Russischen Föderation. Gegenwärtige Entwicklungen und Chancen. Soziale Arbeit, Jg. 56. H.2, pp. 57-63

Connolly, M., & Katz, I. (2019). Typologies of Child Protection Systems: An International Approach. Child Abuse Review Vol. 28: 381–394

Cooper, A. (2000). The vanishing point of resemblance. Comparative welfare as philosophical anthropology. In P. Chamberlayne et al. (Eds): The Turn to Biographical Methods in Social Science. Comparative Issues and Examples, London: Routledge, pp. 90-108

Derr, R. & Galm, B. (2015). Child Protection Systems and Their Influences on Families. An Overview of Five European Countries. In B. Bütow & M. L. Gómez Jiménez (Eds.): Social Policy and Social Dimensions on Vulnerability and Resilience in Europe. Opladen, pp. 87-98

Deutsche Kinderhilfe (2019). Zahlen kindlicher Gewaltopfer nach der Polizeilichen Kriminalstatistik 2018. Pressemitteilung vom 06.06.2019 [online under https://beauftragter-missbrauch.de/presse-service/pressemitteilungen/detail/zahlen-minderjaehriger-gewaltopfer-nach-der-polizeilichen-kriminalstatistik-2018, last accessed on 04.07.19]

Fegert, J. (2017). Studie zu Misshandlung, Vernachlässigung, sexuellem Missbrauch und den Folgen. Fact Sheet zur Studie [online under: www.uniklinik-ulm.de, last accessed on 22.06.2018]

Freymond, N. & Cameron, G. (Eds.) (2006): Towards Positive Systems of Child and Family Welfare. International Comparisons of Child Protection, Family Service, and Community Caring Systems. University of Toronto Press: Toronto

Galm, B. & Derr, R. (2011). Combating Child Abuse and Neglect. Child Protection in Germany. National Report. München: DJI, [online under: URL dji.de/fileadmin/user_upload/bibs/DAPHNEGermanReportLayoutFIN.pdf, last accessed on 11.08.2017]

Gilbert, N. (Ed.) (1997). Combatting Child Abuse: International Perspektives and Trends. New York/ Oxford: Oxford University Press

Gilbert, N., Parton, N., & Skivenes M. (2011). Child Protection Systems: International Trends and Orientations. New York/ Oxford: Oxford University Press

Gritsay, A. G. & Spirina, V. I. (2011). Physical violence in the family as a form of child abuse // Bulletin the Adygea State University. Series 3. Pedagogy and Psychology. Maykop: Adygea State University, pp. 27-32

Herschelmann, M. (2018a). Protection of the rights of children in Germany [Хершельман М. Защита прав детей в Германии (правовые проблемы)]. In: Bulletin of the Moscow Region State University. Series: Jurisprudence, 2018, no. 3, pp. 146-160. DOI: 10.18384/2310-6794-2018-3-146-160

Hetherington, R. (2006). Learning from Difference: Comparing Child Welfare Systems. In: N. Freymond & G. Cameron, (Eds.): Towards Positive Systems of Child and Family Welfare. International Comparisons of Child Protection, Family Service, and Community Caring Systems. University of Toronto Press: Toronto, pp 27–50

Hetherington, R., Baistow, K., Katz, I., Mesie J., & Trowell, J. (2002). The welfare of children with mentally ill parents: Learning from inter-country comparisons. Chichester: Wiley.

Hetherington, R., Cooper, A., Smith, P., & Wilford, G. (1997). Protecting Children: Messages from Europe. Lyme Regis: Russell House Publishing.

Hong, M. (2016): Kinderschutz in institutionellen Arrangements: Deutschland und Südkorea in international vergleichender Perspektive. Wiesbaden: Springer

Johnson, D. E. et al. (2014). From institutional care to family support: Develeopment of an effective early intervention network in the Nizhny Novgorod regian, Russian Federation, to support family care for children at risk for institutionalization. Infant Mental Health Journal, Vol.35(2),172–184

Katz, I., & Hetherington, R. (2006). Co-Operating and Communicating: A European Perspective on Integrating Services for Children. Child Abuse Review Vol. 15: 429–439

Kelly, L., Hagemann-White, C., Meysen, T., & Römkens, R. (2011). Realising Rights. Case studies on state responses to violence against women and children in Europe [online under: https://www.dijuf.de/tl_files/downloads/2011/Projekte/RRS-Report_(Forschungsbericht_EN)_2011.pdf, last accessed on 02.10.2017]

Kindler, H. (2010). Kinderschutz in Europa. Philosophien, Strategien und Perspektiven nationaler und transnationaler Initiativen zum Kinderschutz. In: R. Müller & D. Nüsken (Eds.): Child Protection in Europa. Von den Nachbarn lernen – Kinderschutz qualifizieren. Münster u. a.: Waxmann, pp. 11-29

Kindler, H. (2012). Child protection in Germany. In Schweizerischer Fonds für Kinderschutzprojekte (Ed.): Kinderschutzsysteme: Ein internationaler Vergleich der „Good Practice“ aus fünf Ländern (Australien, Deutschland, Finnland, Schweden und Vereinigtes Königreich) mit Schlussfolgerungen für die Schweiz [online under: http://www.kinderschutzfonds.ch/wp-content/uploads/Bericht_Nett_EN.pdf, last accessed on 11.08.2017]

Kindler, H. (2013). Qualitätsindikatoren für den Kinderschutz in Deutschland. Analyse der nationalen und internationalen Diskussion - Vorschläge für Qualitätsindikatoren (Eine Expertise). In: Nationales Zentrum Frühe Hilfen (NZFH) (Ed.): Beiträge zur Qualitätsentwicklung im Kinderschutz. Paderborn: Bonifatius, S. 1-78 [online under: http://www.fruehehilfen.de/fileadmin/user_upload/fruehehilfen.de/pdf/Publikation_QE_Kinderschutz_6_Expertise_Qualitaetsindikatoren.pdf, last accessed on 02.10.2017]

Kindler, H. & Rauschenbach, T. (2016). Kinderschutz als gesamtgesellschaftliche Aufgabe: Rückblick und künftige Perspektiven. In: Forum Jugendhilfe 02/2016, pp. 4-9

Kojan, B. H. & Lonne, B. (2012). A comparison of systems and outcomes for safeguarding children in Australia and Norway. Child and Family Social Work 2012, 17, pp. 96-107

Krieger, W. (Ed.) (2015): Soziale Arbeit im Ost-West-Vergleich: Soziale Probleme und Entwicklungen der Sozialen Arbeit in Deutschland, Russland, Armenien und Kirgisien. Lage: Jacobs Verlag

Kutscher, N. (2010). Die Rekonstruktion moralischer Orientierungen von Professionellen auf der Basis von Gruppendiskussionen. In R. Bohnsack et al. (Eds.): Das Gruppendiskussionsverfahren in der Forschungspraxis. Opladen & Farmington Hills: Verlag Barbara Budrich, pp. 189-201

Mabbett, D. & Bolderson, H. (1999). Theories and Methods in Comparative Social Policy. In J, Clasen (Ed): Comparative Social Policy: Concepts, Theories and Methods. Blackwell, Oxford, pp 34-56

Merkel-Holguin, L., Fluke, J. D., & Krugman, R. D. (Eds.) (2019). National Systems of Child Protection. Understanding the International Variability and Context for Developing Policy and Practice. Cham: Springer International Publishing

Meysen, T. & Hagemann-White, C. (2011). Chapter 4 – Institutional and legal responses to child maltreatment in the family. In L. Kelly, et al. (Eds.): Realising Rights. Case studies on state responses to violence against women and children in Europe, pp.110-204 [online under: https://www.dijuf.de/tl_files/downloads/2011/Projekte/RRS-Report_(Forschungsbericht_EN)_2011.pdf, last accessed on 02.10.2017]

Müller, R. (2010). „Child Protective Service“ im Vergleich. Ein Modell der wohlsfahrtsstaatlichen Verortung der Fachkräfte im Kinderschutz. In: Müller, R. & Nüsken, D. (Eds.): Child Protection in Europa. Von den Nachbarn lernen – Kinderschutz qualifizieren. Münster u. a.: Waxmann, pp.31-54

Munro, E. R. & Manful, E. (2010). Safeguarding children: acomparison of England’s data with that of Australia, Norway and the United States. [online under: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/183946/DFE-RR198.pdf, last accessed on 02.10.2017]

Nederlands Jeugdinstituut (2012). Combating child abuse and neglect in Germany, Hungary, Portugal, Sweden and The Netherlands. Final Report of Work Stream 1: Collecting and Comparing Strategies, Actions and Practice. Daphne project ‚Prevent and Combat Child Abuse: What works? An overview of regional approaches, exchange and research‘.78 [online under: https://ec.europa.eu/justice/grants/results/daphne-toolkit/en/content/prevent-and-combat-child-abuse-what-works-%E2%80%93-overview-regional-approaches-exchange-and, last accessed on 02.10.2017]

Nesterova, A. (2018). The Russian experience of social and psychological work with children - victims of cruel treatment in the family, oral presentation in Emden 16.05.2018

Nobody's Children Foundation (2009). The Problem of Child Abuse: Attitudes and Experiences in Seven Countries of Central and Eastern Europe. Comparative report 2005-2009 [online under: http://www.canee.net/files/comparative%20report%202009.pdf, last accessed on 16.10.2017]

Nobody's Children Foundation (2010). Comparative Report. The Problem of child abuse [online under: http://www.canee.net/files/COMPARATIVE_REPORT_2010_ENG.pdf, last accessed on 16.10.2017]

Nobody's Children Foundation (2013). The problem of child abuse. Comparative Report from Six East European Countries 2010-2013 [online under: http://www.canee.net/files/OAK_Comparative_Report_Child_Abuse_6_Countries_2010-2013_.pdf, last accessed on 16.10.2017]

OECD (2011). Doing Better for Families, OECD Publishing. [online under: http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264098732-en, last accessed on 09.10.2017]

Sajkowska, M. (2007). Research – The Problem of Chuild Abuse: Attitudes and Experiences in Seven Countries of Central and Eastern Europe. [online under: http://www.canee.net/bulgaria/research_the_problem_of_child_abuse_attitudes_and_experiences_in_seven_countries_of_central_and_eastern_europe, last accessed on 16.10.2017]

Schweizerischer Fonds für Kinderschutzprojekte (Ed.) (2012). Kinderschutzsysteme: Ein internationaler Vergleich der „Good Practice“ aus fünf Ländern (Australien, Deutschland, Finnland, Schweden und Vereinigtes Königreich) mit Schlussfolgerungen für die Schweiz. Zürich [online under: http://kinderschutzfonds.ch/wp-content/uploads/Bericht_Nett_DE.pdf, last accesed on 02.10.2017]

Seckinger, M., Pluto, L., van Santen, E., & Peucker, C. (2016). Das Bundeskinderschutzgesetz und die Kinder- und Jugendhilfe. Eine Auswahl von Ergebnissen zur Evaluation des Bundeskinderschutzgesetzes, Forum Jugendhilfe 02/2016, pp. 24-29

Sicher, P. et al. (2000). Developing Child Abuse Prevention, Identification, and Treatment Systems in Eastern Europe. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Volume 39(5), pp. 660-667

Spirina, V. I. & Spirina, M. L. (2012). Preparing a social worker to prevent domestic violence against a child: a monograph. Armavir: Armavir State Pedagogical University, p. 75

Spratt, T., Nett, J., Bromfield, L., Hietamäki, J., Kindler, H., & Ponnert, L. (2015). Child Proterction in Europa: Development of an International Cross-Comparison Model to Inform National Policies and Practices. British Journal of Social Work (2015) 45, 1508-1525

Statistisches Bundesamt (2018). Pressemitteilung Nr. 344 vom 13. September 2018 [online under: https://www.destatis.de/DE/Presse/Pressemitteilungen/2018/09/PD18_344_225.html, last accessed on 04.07.19]

Thole, W. (2016). Vorwort. In M. Hong (Ed.). Kinderschutz in institutionellen Arrangements: Deutschland und Südkorea in international vergleichender Perspektive. Wiesbaden: Springer, pp. 19f.

UNICEF (2017). A Familiar Face. Violence in the lives of children and adolescents, New York [online under: https://www.dataunicef.org/a-familiar-face--violence-in-the-lives-of-children-and-adolescents.pdf, last accessed on 02.11.2017]

WHO (2014). Global status report on violence prevention 2014. [online under: http://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/violence/status_report/2014, last accessed on 19.10.2017]

Witte, S., Miehlbradt, L., van Santen, E., & Kindler, H. (2016). Briefing on the German Child Protection System. [online under: welfarestatefutures.files.wordpress.com/2016/11/hestia-whitepaper-german-child-protection-system-aug2016.pdf, last accessed on 11.08.2017]

Witte, S., Miehlbradt, L., van Santen, E., & Kindler, H. (2019). Preventing Child Endangerment: Child Protection in Germany. In L. Merkel-Holguin et al. (Eds.): National Systems of Child Protection. Understanding the International Variability and Context for Developing Policy and Practice. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 93-114

Witte, S., Miehlbradt, L., van Santen, E., & Kindler, H. (2017). Kinderschutzsysteme im europäischen Vergleich – Vorstellung des internationalen Forschungsprojektes HESTIA. Forum Erziehungshilfen, 23. Jg., H. 4, pp. 46-48

Wolff, R., Biesel, K., & Heinitz, S. (2011). Child Protection in an age of uncertainity: Germany‘s response. In: N. Gilbert, et al. (Eds.): Child Protection Systems: International Trends and Orientations. New York/ Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 183-203

Wulczyn, F., Daro, D., Fluke, J., Feldman, S., Glodek, C., & Lifanda, K. (2010). Adapting a Systems Approach to Child Protection: Key Concepts and Considerations. New York: UNICEF [online under: https://www.unicef.org/protection/files/Adapting_Systems_Child_Protection_Jan__2010.pdf, last accessed on 24.10.2017]

Author´s Address:

Prof. Dr. Michael Herschelmann

Pia Fischer (BA)

University of Applied Sciences Emden/Leer

Constantiaplatz 4

26723 Emden, Germany

+49 4921 807-1244

michael.herschelmann@hs-emden-leer.de

https://www.hs-emden-leer.de/fachbereiche/soziale-arbeit-und-gesundheit/team/profile/herschelmann-michael/

Author´s Address:

Non-tenured professor Nataliya Komarova, PhD

141014 Mytishchi

st. Vera Voloshinoy, 24.

Moscow region, Russia

+495 780 09 43

nmkomarova@mail.ru

http://mgou.ru

Author´s Address:

Non-tenured professor Tatyana Suslova, PhD

141014 Mytishchi

st. Vera Voloshinoy, 24.

Moscow region, Russia

+495 780 09 43

Sibir812@mail.ru

http://mgou.ru

Author´s Address:

Prof. Dr. Albina Nesterova,

141014 Mytishchi

st. Vera Voloshinoy, 24.

Moscow region,

Russia

+495 780 09 43

anesterova77@rambler.ru

http://mgou.ru