Coping professionally with closeness: Caught between children’s needs and self-protection[1]

Meike Wittfeld, University of Duisburg-Essen

1 Introduction

On January 28, 2010 the daily newspaper, Berliner Morgenpost reported on sexual violence at the German catholic boarding school Canisius Kolleg (Anker & Behrendt, 2010). This article was the starting point of a series of disclosures of many more cases of sexual violence in pedagogical institutions and a new public debate on the topic (Wazlawik et al., 2019; Fegert & Wolff, 2015). Although the problem of sexual violence in educational institutions had been public knowledge in Germany, at least since the 1990s, (Conen, 1995; Fegert & Wolff, 2002), it had received little public attention until 2010 (Hoffmann, 2015; Görgen & Fangerau, 2018).

In English-speaking countries, the debate and public attention started about ten years earlier. Here, research on sexual violence in institutions had been conducted since the late 1990’s (Timmerman & Schreuder, 2014; Hobbs et al., 1999). Since the 1990’s, public attention has led to numerous commissions to investigate sexual violence in institutions: In England (Warner 1992; Utting 1997), Wales (Waterhouse 2000), Ireland (Ryan 2009; Murphy 2009; Murphy et al. 2005) and the USA (John Jay College 2006; the National Review Board for the Protection of Children and Young People 2004).

What was new in Germany in 2010, was a shift in public, political and academic attention (Behnisch & Rose 2012). In addition to the increase in media coverage, the new definition of relevance is linked to very rapid political measures (UKASK, 2018; UBSKM 2020) and a strengthening of the research landscape (Wazlawik et al., 2019). It would be too much to go into detail at this point. What are important for this article are studies that connect the media and social attention with challenges for professional action.

In Germany, studies in the field of elementary education show public debates about sexual violence in pedagogic institutions can lead to the circumstance that male professionals feel that they are under general suspicion of committing sexual violence against children. As a result, they adapt their pedagogical actions and avoid physical contact with the children they care for (Cremers et al. 2010, Buschmeyer, 2013, Rohrmann 2014, Diewald, 2018). In a similar manner, a German umbrella organization of social service organisations reports that there is also massive uncertainty in the area of residential child and youth care (Abrahamczik et al. 2013). For the UK, Jan Horwarth and Laura Steckley were able to show that the media attention on sexual violence by residential care professionals poses comprehensive challenges for professionals working in this field (c.f. Horwath, 2000, Steckley 2012). “The concerns about possible allegations of abuse by resident would seem to dominate workers' approach to potentially abusive situations. This means, in some cases, that the needs of the worker can take precedence over the needs of the child.” (Horwath, 2000, S.187). The results from the field of day-care centres and the UK indicate that the issue of sexual violence in institutions also has an impact on the professional behaviour of the professionals working there.

The research, which is the basis of this article, reconstructs a connection between the media debate on sexual violence in Germany and a change in the actions of professional staff with regard to educational closeness. Empirically, the project has shown that the topic of sexual violence in institutions plays a role in everyday professional life, especially in balancing proximity and distance.

At this point, it is important to underline that acts of sexual violence against warded persons are always intentional and should not be blurred with pedagogical closeness. Nevertheless, empirical situations of closeness become relevant against the background of the social discussion on sexual violence in educational institutions. For this reason, the following section will first take a theoretical look at situations of closeness (2). In addition, an empirical example will be used to illustrate how the presence of the topic of sexual violence, or the fear of professionals of being suspected of it, leads to pedagogic closeness being restricted (3). The article finishes with the conclusion, that professionals are caught between children’s needs and self-protection.

2 Closeness in residential care: A professional challenge

Residential Care is the oldest form of child and youth welfare. In the area which is now Germany, its roots go back to the Middle Ages, when Christian orphanages were first established. The primary purpose of these charitable institutions was to provide children with shelter and to satisfy their basic needs for food and warmth. Later on, the orphanages were used to obtain cheap labor. Emotional needs of the children and pedagogical relationships between the caregivers and the care recipients did not play a major role at that time (cf. Kappeler, 2018).

At the beginning of the 19th century, the first pedagogical ideas regarding the placement of children in homes were developed. One of the first protagonist was Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi is best known in the German-speaking world for his education of the poor to poverty and his family-oriented parlour pedagogy (Wohnstubenpädagogik). In his letter from Stans of 1799, Pestalozzi describes how he passionately devoted himself to eating and sleeping together with the children in order to gain their trust through bodily and emotional closeness. This trust - Pestalozzi also talks about love - along with satisfying basic needs for food and shelter are the basis for educators being able to teach and rear those in their care (cf. Pestalozzi, 1799/1932). Taking this perspective, Pestalozzi emphasizes how pedagogic relationships are linked inextricably to bodily and emotional closeness; and, going beyond this, that meeting such needs is essential if one wants to engage in a pedagogic interaction.

Johann Hinrich Wichern (*1808) can be regarded as the founder of the "family principle in home education" (Moch 2018, p. 635). He founded a hostel that he called “Rauhes Haus” to provide refuge, free of alcohol and gambling for young men. In his pedagogic approach, he used the family principle to teach adolescents moral principles (Wichern 1949). He saw his efforts as an anti-capitalist, socialist and communist position that scandalized the living conditions of young people and propagated social upheaval. In contrast, Wichern's pedagogical intention of conveying bourgeois family values was to stabilize social conditions through social reforms. In his understanding of the family, he as well as Pestalozzi idealized a romantic image of the bourgeois family, which was considered the nucleus of a successful society. Marriage, children, and Christian morality were considered the epitome of the family (cf. Kappeler, 2018). This orientation devalued other life plans and described families that did not correspond to this ideal as deficient. Similar to Wichern's pedagogy, the pedagogy of Don Bosco in Italy aimed at saving poor young people from the streets. What was new about these pedagogical perspectives was that they saw a potential educability of children and young people (cf. Kappeler & Hering, 2017).

A very important part of all three pedagogical approaches was to use emotional closeness in order to build a pedagogical relationship. Children and young people were to be met with warmth and affection. The positive, normatively highly charged image of the bourgeois nuclear family became the guiding principle for many reform educational ideas. The pedagogical approaches are regarded as groundbreaking approaches for the development of pedagogy. Nevertheless, the approaches where highly normative, intending to form the children as subordinate citizens. Moreover, their reach for pedagogical practice was very limited. Rigid discipline and violence continued to be used in most institutions. Especially for Germany, there has to be mentioned that, from the beginning of the 20th century, children were divided into being valuable and non-valuable for the nation. Various institutions were installed and only the valuable ones were given a more appreciative attitude, which included the family. During the Nazi era, children and young people considered inferior were interned in camps (Kappeler, 2018).

In these times the German pedagogue Hermann Nohl also addressed the relationship and the closeness between educator and student: “Hence, the basis of education is the passionate relationship of a mature person with one who is becoming a person, and a relationship for its own sake, so that this person embarks on his or her life and gains his or her form” (Nohl, 1935/1970, p. 134, translated). By referring to the passionate nature of the relationship, Nohl is indicating that educators also have to devote themselves emotionally to their work and their relationship with the children in order to establish a basis with which to engage with them purposefully. While Nohl’s theoretical foundation of the pedagogical relationship (in German known as “Pädagogischer Bezug”) has been highly influential in German pedagogy, it has to be mentioned, that Nohl sympathized with the Nazi regime and his work contains national socialist, racist and highly patriarchal (Ortmeyer, 2008).

Pestalozzi, Wichern, Don Bosco and Nohl assume an emotional need in the young, and that the task of the educators is to address this need. This also means becoming emotionally and spatially close to children and youths. The responsibility for these results not only from the role of the professional, but also from the generational difference that conceives the adult as “finished” and the child as “becoming.” The task of the educator is also to shape the unfinished child through a relationship of trust. Nonetheless, Nohl’s understanding of the pedagogic relationship includes not only closeness but also distance. He assumes two complementary poles to the pedagogic relationship (cf. Rentdorff, 2012, p. 91): “The pole of motherly love stands for ‘indulgence and direct closeness’ and responds to the needs of the individual child; the pole of fatherly chivalry, for the ‘factual neutrality’ that introduces the child to the community and separates the child from the mother (ibid.). Although the two poles complement each other, Nohl evaluates the fatherly, educational distance as the desirable state that first ‘permits a qualitatively higher level of education’” (Rentdorff 2012, p. 94, translated). While this quotation strongly mirrors Nohl's patriarchal, anti-feminist way of thinking, it also makes it clear that both closeness and distance play a major role in pedagogical relationships and must be interrelated with each other again and again.

Contemporary educational science is paying even more attention to the conflicts between closeness and distance in the pedagogic context that Nohl already suggested. A look at the theory of the profession is sufficient here to better grasp the emerging tension:

Werner Helsper defines “the tense relation between closeness and distance” as one of the four fundamental antinomies of contemporary pedagogy. Pedagogic professionals experience repeated exposure to the criticism of “too much or too little emotional engagement” (2006, p. 25, translated). The tension emerges because “the professionalization of pedagogic work removes intimacy from the affective and unique relationship between parents and their child” (ibid.). This differentiation implies an essential difference between the parents’ relationship to their children and the professional relationship to young persons.[2] The latter is temporary, is not based on love, the persons involved (professional and child) can be exchanged at random, and the professionals remain shadowy in the sense that they are present as professionals and not as “complete persons”.

Both in the historical debates and in Helsper's current approach it is clear that the professional closeness relationship is always defined in terms of family. It has to be close if it is to be effective, but it should not be as close as that between children and their parents.

For the field of residential childcare, Doris Bühler-Niederberger points out very similar differences between the structural conditions of family relationships and institutional relationships. Even though that most residential childcare is currently based on a family-like ideal, it cannot honour the structural characteristics of permanency and uniqueness. Indicating that what may seem to be familial relations actually remain an organized “deception” (Bühler-Niederberger, 1999, p. 337, translated). The complexity of the relationships in residential child care is also discussed by Andrew Kendrick who argues:

Yet, we have seen that practice in residential care often echoes family practices, and children and young people use the language of family and kinship in describing their positive experiences. Drawing on theoretical developments in the sociology of the family, […] we need to locate residential practice and the relationships between children and residential staff within a wider conceptual framework. It is in understanding children’s and young people’s centrality in the complex mesh of relations, relatedness and relationships that residential child care must find its true potential. (Kendrick 2013, 83)

While Bühler-Niederberger is more critical of the relationship to family, Kendrick sees a potential for the children to be represented by the metaphor of family closeness.

Although the uniqueness and permanency of the relationship cannot be achieved due to the described obstacles, the pedagogic relationship between caregivers and children in residential child care is nonetheless not comparable with any other professional relationship. In contrast to other service professions, child care workers are unable to carry out their professional activities completely at a professional distance, because their everyday work is very strongly entangled with the daily lives of their clients (cf. Müller, 2012). It is not possible for professionals to separate themselves in their work completely from the “intimacy of real life” (Müller, 2012, p. 150, translated) as, for example, an analyst can do, because they have to struggle jointly with their clients in real and everyday life. “This strongly confronts educators with demands to achieve a balance and to cope with the inherent tension within pedagogic work between emotional closeness and a constraining distance, between the poles of a family-like intimacy and a comparatively indifferent coldness” (Helsper, 2006, p. 30, translated). Following Müller and Helsper, it is necessary to examine what the professional approach to situations of closeness actually looks like in practical terms.

3 Professional coping strategies with situations of closeness in residential child care

The elaborated ideas on the pedagogic antinomy of closeness and distance presented form the backdrop for interpreting the following empirical findings. The empirical study tackles the question how residential child care workers in Germany are confronted with the topic of sexual violence in their daily work and how they deal with it against the background of a massive public interest in sexual violence in pedagogic institutions.

To address this issue, six group discussions were carried out with teams working together in residential child care between winter 2011 and spring 2013. Between three and six professionals took part in each discussion, and teams always contained both men and women. The group discussions[3] between the professionals followed the question whether sexual abuse by pedagogues is a relevant topic for the professionals and further which role does it have in the daily work in the residential care.

One central finding from the research project was that the relevance to the professionals of the topic of sexual abuse was essentially a question of how situations of closeness were shaped between them and the children in their care (see also Wittfeld, 2016). The reasons for closeness between the professionals and the children are manifold and they occur on an everyday basis. This can be due to the given spatial arrangements—for example, when there is only one bathroom that has to be used jointly; or they arise in specific situations that require body contact between children and staff such as helping them to shower, cleaning them up after defecation, carrying out compulsory searches, or dressing wounds. Further situations emerge because children themselves communicate an emotional need for closeness to the staff. For example, children like to be hugged, wish for closeness when going to bed, and want to be consoled when they are sad. The staff also report situations that have sexual overtones: when, for example, youths get hold of the underwear of staff members or exhibit explicitly sexualized behaviour towards professionals. They likewise report situations in which (former) colleagues have cuddled or sought emotional affection in ways associated with sexual intimacy.

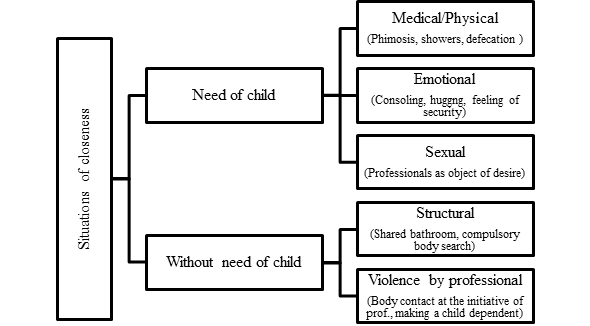

By systematizing situations of closeness, the research suggests to distinguish initially between those situations that either respond to the need of a child or do not address the need of a child in a specific situation but nonetheless influence a child’s well-being (see figure 1). Needs for closeness can be broken down further into physical/medical, emotional and sexual needs.

Figure 1: Systematization of situations of closeness with empirical examples

When addressing the topic of sexual abuse, the group discussions described mostly those situations of closeness that emerge because of the needs of the child and which are in themselves problematic. In these situations, the child’s need always conflicts with other interests. This conflict will be clarified here through two empirical examples taken from one of the team’s group discussion. In the following reconstruction of the empirical data two sequence[4] will be analysed. Parts of the original conversation of the professionals are followed each by an analysis. The second sequence is broken down into short sections to make it easier to follow. Four professionals participated in the group discussion, all of whom have been working together for at least ten years in the same residential group. The thee professionals speaking here are men.

Sequence 1

Deich : well, after you told us a bit about the further training course, I made up my mind that, okay, you’re going to handle this carefully, your eyes are open, you must try to see things more clearly, and I am trying; just to carry on working as before; without having to worry; (.) is that alright now when I watch a child having a shower because of a concern that he might have phimosis; I leave the door open on purpose and look to see if it is okay, eh (.) where the pediatrician is also saying that you should even put some cream on the, (.)penis, @where I then said@[5]

Amman: L yes

Wallfaß: can’t do that, not allowed to, I’m not doing it, it’s too risky for me, actually complete nonsense, I would definitely do it for my own son; er for that

Amman: L mhm

Wallfaß: sensible- and in the work that you, do with children eh who already have problems

Amman: L yes

Wallfaß: enough in the world, you can’t do that then; it’s somehow like that, (2)

(GD6 1054–1060)

The management of the residential youth care where this team works has recently set very strict action guidelines on how professionals should deal with situations of closeness. As a result, Mr. Deich feels a need to be sensitive to this issue. Nonetheless, the guidelines have made him anxious. This is reflected in an uncertainty about how to act: According to the guidelines, it would seem highly problematic to administer a cream lotion to a boy’s penis, even though this would be a medically necessary action advised by a doctor, and Mr. Deich himself considers this a meaningful measure. However, in line with the organizational guidelines, he does not administer it. In this way, he avoids the risk of being suspected of sexual violence.

Classifying this sequence into the systematization introduced above, it becomes clear that this is a medical need of the child that is appraised as being problematic. The problem arises through the two competing orientations: on the one side, the logic of acting according to the needs or the well-being of the child: on the other side, that of complying with the action guidelines. The former is generalized in this study as the orientation toward the needs of the child; the latter is conceived as an orientation toward self-protection. In this case, the decision is made in favour of the action guidelines. The need of the child is made secondary to the well-being of the professional: In order to avoid suspicion, he follows the strict prevention strategy, although this means that he can no longer work in a “sensible” way.

Sequence 2

Wallfaß: yes yes that I=my interest, what’s interesting about that is, that it has nothing to do with the fact of sexual abuse itself, (.) that is well, perfidious,

Brandt: L that is a means isn’t it,

Wallfaß: is so perfidious that you don’t even have to to talk about it, it is simply just the way it makes you uncertain, what’s that doing to me;

The second sequence starts with the reaction to the initial question that launched the group discussion: “whether and how sexual violence becomes a topic for professionals in their work.” Mr. Wallfaß starts off by clarifying that what is relevant for the team is not sexual abuse itself, but a specific feeling of uncertainty. It is not necessary to address sexual abuse at this point—it is out of the question and its rejection is self-evident. In contrast, however, the feeling of uncertainty and the question about the influence this exerts are highly relevant. This framework of distancing oneself from sexual abuse now makes it possible for Mr. Wallfaß to talk about what is relevant to him (cf. Wittfeld, 2016).

Wallfaß: no, I can still remember that when I started working as a trainee educator many years ago, that was the recommendation of a colleague, and NEVER go into a room alone with a boy; (.) yes and I have actually followed this guideline to the present day. (.) not (.) to protect that child from something,

Amman: L mhm

Wallfaß: but simply because of the uncertainty in the face of yes in the face of this aspersion; because German law is based on the presumption of innocence, everyone is, is held to be innocent until the opposite is proven, but simply not in this case; even if something, if somebody comes and claims that the colleague here is up to something with children, then it’s bang, out (…). I think a few months ago there was yes, that case in a kindergarten again, I don’t know the names of the children now, I shall just say Robert always goes to the toilet with me

Brandt: L yes

Wallfaß: (.) the educator called Robert was then also suspended from service immediately, he was thrown out, and sometime later by chance it came out no, (.) that the child with whom he was in the toilet together who went was

Amman: L the child’s name was Robert no; I read it

Wallfaß: Robert the child; only for the educator, he lost his job;

Deich: L mhm

Amman: yes

Wallfaß: no, he was finished;

Mr. Wallfaß continued to explain the feeling of uncertainty. This already begins when he started work 35 years ago and was still in training. With the example of a colleague who warns him against being alone with a boy in a room, he points to the continuous presence of uncertainty brought about by situations in which professionals and children come close together. Avoiding the situation is not in the interest of the child for whom an undisturbed talk might be very good, but in the interest of the professional who protects himself from “this aspersion.” This specifies the reason for the uncertainty that increases immediately in the next sentence. By itself “aspersion” might be unpleasant and perhaps stressful for the individual. However, this is joined “in this case” by the suspension of the “presumption of innocence.” The case is then substantiated with “the colleague here is up to something with children.” This formulation paraphrases sexual violence but remains unsubstantiated. Even just claiming that a professional engages in sexual violence is sufficient to judge him: “then it’s bang, out.”.

Mr. Wallfaß substantiates his premise with the support of Mr. Amman and Ms. Brandt by citing a concrete case that both he and Mr. Amman are aware of from the media. He refers to a media article in which a child care worker got under false suspicion. The example stands out in two ways: first, because the article states that the assumption that the educator was accompanying the child to the toilet is not true. Hence, a rumor has emerged here that led to a suspension even before it was investigated. Second, because, once again, a not necessarily problematic and even everyday situation of closeness is being equated with sexual violence: A member of the Kindergarten staff accompanies a boy to the toilet. Alongside confirming what was discussed previously, this media example makes it clearer that even the clarification of what happened does not lead to the rehabilitation of the educator. He “lost his job” permanently. Mr Wallfaß concludes, that he can no longer work in his profession. That fact, that Mr. Wallfaß quotes this story from the media and his reaction to it show how deeply he is influenced by the societal discussion on sexual violence in institutions.

Wallfaß: (.) and then the question for me is how do I deal with that; how do I know how to protect myself, from ever becoming suspect; do I have to (.) build up a wall between myself and the children that is not very meaningful pedagogically; that means when Jaqueline gets up in the morning or returns from school, has had a hard day, or has somehow or other, you know what I mean, when she comes I’m not allowed to take her in my arms and comfort her;

Amman: mhm

Wallfaß: yes; (.)no I don’t permit that permit that any more, if a stranger

Deich: L alone, however alone,-

Wallfaß: a third person were to see me; and were to then interpret that; (.) and take that interpretation further; I’d be standing there with my back against the wall;

In this section, Mr. Wallfaß now relates his ideas about this uncertainty to his current work practices. His colleagues support him in this, thereby indicating their agreement. The fear of being talked about negatively and prejudged has strengthened over time and is leading him to change his working practice in order to avoid becoming suspect, because this, as pointed out above, would mean the “end.” Mr. Wallfaß talks about a “wall” that he builds up between himself and the children. This wall metaphor illustrates the distance that Mr. Wallfaß adopts completely deliberately. He avoids situations of closeness even when these would have been pedagogically meaningful as in the situation he describes with Jaqueline. What he does depends decisively on a “third-person stranger” who could interpret the situation to his disadvantage or as sexual violence. The use of the subjunctive mood indicates that this in no way requires the real existence of a concrete third party. To judge the situation, it suffices that it could potentially be misunderstood. The image of “standing there with my back against the wall” and the associations with a firing squad this elicits underlines the intractability of the situation.

Just as in the first sequence, there is a conflict here between the orientation toward the needs of the child and the orientation toward self-protection. Even though Mr. Wallfaß would prefer to act otherwise for professional reasons, his uncertainty is so great that the orientation toward self-protection predominates.

Amman: that means for you, that you, when when when it comes to sexual abuse, you are always caught between what do I need to protect myself and what

Wallfaß: L between,

Amman: that child needs for its development

Wallfaß: between what is pedagogically permissible, what is necessary, all of you look at, look at tall Devin, when he is just having problems with his girlfriend and is then totally down; and as Regina says, then what he’d like to do more than anything else is sit on your lap; a quick hug, and just fetch the comfort the portion of comfort that is incredibly meaningful from a pedagogic perspective and incredibly necessary, but which against this background, the sexual, the risk of being accused of sexual abuse, I then don’t do; (3) and for me that also takes away a great big chunk

Amman: L mhm

Wallfaß: of the quality of work that I could also give but do not give or not GIVE without somehow having my character maligned or placing myself at risk.

Mr. Amman and Mr. Wallfaß formulate the summary conclusion of the sequence together. They abstract from the previous examples and say how they are “caught between” the protection of professionals and the needs of the children or that which either is or is not “pedagogically permissible.” They reveal a far-reaching reflection on an action dilemma that they cannot resolve, and that leads to a reduction in the quality of their work. Mr. Wallfaß introduces a further everyday situation that differs somewhat form the other. This concerns a boy “tall Devin” who has problems with “his girlfriend”. Even this somewhat older boy, for whom close bodily contact with the educator may no longer be common practice, is assigned a need for closeness at certain moments. Responding to this need would be meaningful; however, because of the need to protect the staff member, this is denied.

4 Coping professionally with closeness: Caught between children’s needs and self-protection

The beginning of this article pointed to the fundamental nature of the antinomy between closeness and distance for pedagogic relationships. The theoretical demand that professionals should be able to cope with such situations of closeness is relatively uncontroversial: The central aspect is “that professionals are sufficiently trained to creatively link together and convey closeness and distance to their clients and their problems” (Dörr & Müller, 2012, p. 8, translated). However, this is already a major challenge. Especially because residential care has to relate itself to care responsibilities, which are for the broad majority of children, covered by their family of origin.

The empirical examples taken from the research project show that this “demand to achieve a balance” (Helsper, 2006, p. 30, translated) acquires a further new dimension against the background of the societal discussion on sexual violence in institutions. The balance that has to be achieved pedagogically has been irritated and is leading to a greater interpersonal distance in the actions of residential care workers—a distance that the team presented their views as being problematic and in part also unprofessional—because the “quality of work” suffers. The emotional and physical needs of children are in parts disregarded. The team described the challenge that their work needs to be unambiguous. At any point in time, an imaginary third person needs to be able to appraise their work as being harmless. They are unable to perform medically or pedagogically justifiable actions, because it would be possible for them to be misunderstood by a third person lacking any knowledge of the context.

The failure to master this challenge cannot be avoided, because mediating between closeness and distance can never be unequivocal. It always remains “subject to risks of uncertainty. Pedagogic success cannot be rendered technically safe in this way, and pedagogic activity is necessarily caught between knowledge of the abstract rules and the relation to the specific case that has to be dealt with in the concrete situation” (Helsper, 2006, p. 30, translated).

With all this necessary vagueness, what remains clear is that professional activity must be directed toward the needs of the child. Even if mistakes may occur in achieving the balance between closeness and distance, it would be professional to discuss these subsequently and to process them accordingly. It needs places to have these discussions and to discuss fears of professionals. And it needs an understanding of prevention that takes into account the necessary ambiguity of educational action.

References

Abrahamczik, V., Hauffe, S., Kellerhaus, J. T., Küpper, S., Raible-Mayer, C., & Schlotmann, H.-O. (2013). Nähe und Distanz in der (teil-)stationären Erziehungshilfe. Eine Ermutigung in Zeiten der Verunsicherung. Freiburg im Breisgau: Lambertus (Beiträge zur Erziehungshilfe, 41).

Behnisch, M. & Rose, L. (2012). Frontlinien und Ausblendungen. Eine Analyse der Mediendebatte um den Missbrauch in pädagogischen und kirchlichen Institutionen des Jahres 2010. In: S. Andresen & W. Heitmeyer (Eds.): Zerstörerische Vorgänge. Missachtung und sexuelle Gewalt gegen Kinder und Jugendliche in Institutionen. Weinheim [u.a.]: Beltz Juventa, (pp. 308–328).

Bohnsack, R. (2010). Documentary Method and Group Discussions. In: R. Bohnsack, N. Pfaff & Weller, W. (Eds.): Qualitative analysis and documentary method in international. Opladen & Farmington Hills, Barbara Budrich (pp. S. 99–124).

Bühler-Niederberger, D. (1999). Familienideologie und Konstruktion von Lebensgemeinschaften in der Heimerziehung. In: H. E. Colla & M. Winkler (Eds.), Handbuch Heimerziehung und Pflegekinderwesen in Europa (pp. 333–341). Neuwied: Luchterhand.

Buschmeyer, A. (2013). Zwischen Vorbild und Verdacht. Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden.

Conen, M.-L. (1995). Sexueller Mißbrauch durch Mitarbeiter in stationären Einrichtungen für Kinder und Jugendliche. In: Praxis der Kinderpsychologie und Kinderpsychiatrie (4), (pp. 134–140.)

Diewald, I. (2018). Männlichkeiten im Wandel. Bielefeld: transcript Verlag.

Cremers, M., Krabel, J., & Calmbach, M. (2010). Männliche Fachkräfte in Kindertagesstätten. Eine Studie zur Situation von Männern in Kindertagesstätten und in der Ausbildung zum Erzieher. (Eds.). Bundesministerium für Familie, Senioren, Frauen und Jugend. BMFSFJ. Berlin.

Dörr, M., & Müller, B. (2012). Nähe und Distanz. Ein Spannungsfeld pädagogischer Professionalität. Weinheim und Basel: Beltz Juventa.

Fegert, J. M., Wolff, M. (Eds.) (2002). Sexueller Missbrauch durch Professionelle in Institutionen. Prävention und Intervention; ein Werkbuch. Weinheim: Beltz.

Fegert, J. M.; Wolff, M. (2015). Eine neue Qualität der Debatte um Schutz vor Missbrauch in Institution. In: J. M. Fegert & M. Wolff (Eds.): Kompendium „Sexueller Missbrauch in Institutionen“. Entstehungsbedingungen, Prävention und Intervention. Weinheim, Basel: Beltz Juventa, (pp. 15–34).

Helsper, W. (2006). Pädagogisches Handeln in den Antinomien der Moderne. In H.-H. Krüger & W. Helsper (Eds.), Einführung in Grundbegriffe und Grundfragen der Erziehungswissenschaft (7th ed., pp. 15–34). Opladen [u.a.]: Budrich.

Kendrick, A. (2013). Relations, relationships and relatedness: residential child care and the family metaphor. In: Child & Family Social Work 18 (1), (pp.77–86).

Kappeler, M., & Hering, S. (2017). Geschichte der Kindheit im Heim. Potsdam: Fachhochschule Potsdam.

Görgen, A., & Fangerau, H. (2018). Deconstruction of a taboo: press coverage of sexual violence against children in pedagogical institutions in Germany 1950–2013. Media, Culture & Society 40 (7), S. 973–991. DOI: 10.1177/0163443717745120.

Hoffmann, U. (2015). Sexueller Missbrauch in Institutionen - eine wissenssoziologische Diskursanalyse. In: J. M. Fegert & M. Wolff (Eds.): Kompendium "Sexueller Missbrauch in Institutionen". Entstehungsbedingungen, Prävention und Intervention. Weinheim, Basel: Beltz Juventa, (pp. 37–49.)

Horwath, J. (2000). Childcare with gloves on: protecting children and young people in residential care. In: British Journal of Social Work 30 (2), (pp. 179–191.)

John Jay College (Eds.) (2006). Supplementary Report. The Nature and Scope of Sexual Abuse of Minors by Catholic Priests and Deacons in the United States, 1950–2002. Washington, DC: United States.

Kessl, F., Koch, N., & Wittfeld, M. (2014). Familien als risikohafte Konstellationen: Zu den Grenzen und Bedingungen (nicht nur) professional-pädagogischer Familialisierungstrategien. In S. Fegter, C. Heite, J. Mierendorff, & M. Richter (Eds.): Neue Aufmerksamkeit für Familie und Eltern (AT), Sonderheft der Neuen Praxis, Nr. 12

Müller, B. (2012). Nähe, Distanz, Professionalität. Zur Handlungslogik von Heimerziehung als Arbeitsfeld. In M. Dörr & B. Müller (Eds.), Nähe und Distanz. Ein Spannungsfeld pädagogischer Professionalität. Weinheim und Basel: Beltz Juventa.

Murphy, F. D., Buckley, H., & Joyce, L. (2005). The Ferns Report. Dublin.

Murphy, Y. (2009). Report by Commission of Investigation into Catholic Archdiocese of Dublin. Dublin: Government Publications.

Nohl, H. (1935/1970). Die pädagogische Bewegung in Deutschland und ihre Theorie (7th ed.). Frankfurt a.M.: Schulte-Bulmke.

Ortmeyer, B. (2008). Herman Nohl und die NS-Zeit. Forschungsbericht. Frankfurt, M.: Fachbereich Erziehungswiss. der Johann-Wolfgang-Goethe-Univ (Frankfurter Beiträge zur Erziehungswissenschaft: […], Reihe Forschungsberichte, 7.2).

Pestalozzi, J. H. (1799/1932). Pestalozzis Brief an einen Freund über seinen Aufenthalt in Stanz. In: Pestalozzi: Sämtliche Werke, vol. 13. Berlin: Gruyter, (pp. 1–32).

Przyborski, A., & Wohlrab-Sahr, M. (2014). Qualitative Sozialforschung. Ein Arbeitsbuch (4th revised ed.). München: Oldenbourg.

Rendtorff, B. (2012). Überlegungen zu Sexualität, Macht und Geschlecht. In T. Werner, Baader, M., Helsper, W., Kappeler, M., Leuzinger-Bohleber, M. & Reh, S. Sexualisierte Gewalt, Macht und Pädagogik (pp. 90–100). Opladen: Barbara Budrich.

Rohrmann, T. (2014). Männer in Kitas: Zwischen Idealisierung und Verdächtigung. In: J. Budde, C.Thon & K. Walgenbach (Eds.): Männlichkeiten. Geschlechterkonstruktionen in pädagogischen Institutionen. Opladen, Berlin & Toronto: Verlag Barbara Budrich (pp. 67–84)

Ryan, S. (2009). Final Report of the Commission to Inquire into Child Abuse. Ed. by Commission to Inquire into Child Abuse (CICA). Dublin.

Steckley, L. (2012). Touch, Physical Restraint and Therapeutic Containment in Residential Child Care. In: The British Journal of Social Work 42 (3), (pp. 537–555.).

The National Review Board for the Protection of Children and Young People (Eds.) (2004). A Report on the Crisis in the Catholic Church in the United States. Washington, D.C.: United States.

Unabhängiger Beauftragter für Fragen des sexuellen Kindesmissbrauchs (UBSKM) (28.01.2020). Bilanz 10 Jahre „Missbrauchsskandal“. Online https://beauftragter-missbrauch.de/presse-service/pressemitteilungen/detail/bilanz-10-jahre-missbrauchsskandal, 29.01.2020.

Unabhängige Kommission zur Aufarbeitung sexuellen Kindesmissbrauchs (UKASK) (2019). GESCHICHTEN DIE ZÄHLEN. BILANZBERICHT 2019. Band I.

Utting, W. B. (1997). People like us. The report of the review of the safeguards for children living away from home. London: HMSO.

Warner, N. (1992). Choosing with care: the report of the committee of inquiry into the selection, development and management of staff in children's homes. Norman Warner, Chair. Hg. v. HMSO/Great Britain. Department of Health. London.

Waterhouse, R. (2000). Lost in care. Report of the Tribunal of Inquiry into the abuse of children in care in the former County council areas of Gwynedd and Clwyd since 1974. Great Britain. London

Wazlawik, M., Dekker, A., Henningsen, A., Retkowski, A., & Voß, H.-J. (2019). Einleitung. In: M. Wazlawik, H.-J. Voß, A. Retkowski, A. Henningsen & A. Dekker (Hg.): Sexuelle Gewalt in pädagogischen Kontexten. Aktuelle Forschungen und Reflexionen. Wiesbaden, Ann Arbor, Michigan: Springer VS.

Wittfeld, M. (2016). Zwischen Schutzauftrag und Generalverdacht. Widersprüchliche Anforderungen an Fachkräfte stationärer Kinder- und Jugendhilfe In O. Bilgi, M. Frühauf, & K. Schulze (Eds.), Widersprüche gesellschaftlicher Integration – Zur Transformation Sozialer Arbeit. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Author´s

Address:

Meike Wittfeld

Universität Duisburg-Essen

Universitätsstraße 2, D-45141 Essen

meike.wittfeld@uni-due.de

https://www.uni-due.de/schule_und_jugendhilfe/meike_wittfeld.php