Co-production Approaches in Social Research with Children and Young People as Service Users - Challenges and Strategies

Timo Ackermann, Alice Solomon University of Applied Sciences Berlin

Dirk Schubotz, Queen’s University Belfast

1 Introduction

In this contribution we are considering the state of the art of participatory and co-production approaches in social research, in particular research involving children and young people as service users. We will first look at the origins and theoretical perspectives of participatory research and we will then discuss some ethical considerations for research with children and young people. Finally, we will focus on some of the practical challenges in each stage of participatory research projects before concluding with reflections on future challenges for participatory research with children and young people. Our aim is to link theoretical, ethical and practical aspects of participatory research with children and young people before concluding with a reflection on the challenges that need to be addressed when moving the participatory agenda forward.

It is thought that the term ‘participatory research’ was first used by Marja Liisa Swantz in her experimental pilot survey of skills in rural Tanzania (Swantz, 1975). The original proponents of participatory research approaches like Swantz, but also notably Hall (1975) and Susman and Evered (1978) who criticised the positivist research practice, which was the dominant conventional practice at that time, for its inadequacy and lack of capacity to generate practical and applicable knowledge. Participatory research, on the other hand is not just about researchers understanding the lives of people and communities who are the subject of a research study, but about mutual understanding and collective action to make positive changes.

When we use the term ‘conventional’ research here, we do not deny the multifaceted character of such research nor its legitimacy; we simply relate to the fact that in conventional research the relationships that participants have with researchers or with other people in the research process are often minimised or treated as redundant or superfluous, rather than being central, as is the case in participatory research practice where the aim is to research with rather than on participants (Reason und Bradbury 2001; Kemmis und McTaggart 2007; Rodríguez und Brown 2009; Kemmis et al. 2014; Bergold und Thomas 2010, 2012). Participatory approaches are therefore characterised by a convergence of science and practice (Bergold und Thomas, 2012), where subjects of scientific enquiry become partners or co-researchers in an investigation.

2 Principles and building blocks of participatory research

Whether they are involving children and young people or not, empowerment is a central, albeit not uncontested (Eylon, 1998), motivation in collaborative research approaches. Fundamentally, collaborative approaches challenge the power differential between researchers and research participants that conventional, often objectivist research approaches, are mostly characterised by.

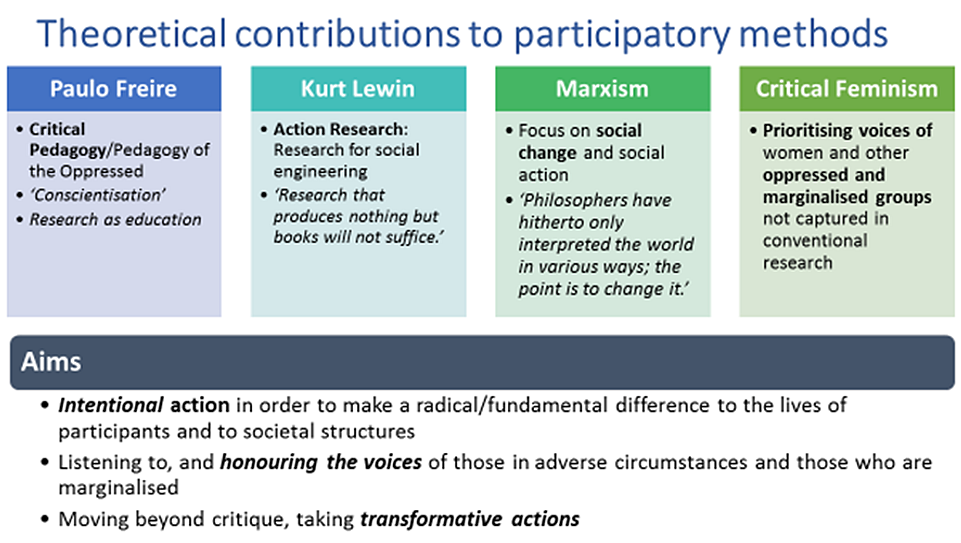

The theoretical underpinnings of participatory research approaches go back further than the 1970s. The first central pillar is Kurt Lewin’s action research - research not just for scientific discovery, but for social engineering and positive social change. In Lewin’s view, ‘research that produces nothing but books does not suffice’ (Lewin, 1946, p. 35).

Paulo Freire’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed (1971) is a particularly influential theoretical contribution in Participatory Action Research (PAR) approaches, but has relevance more broadly in participatory research. Freire regards research itself as an educative tool with the aim to raise consciousness for the status quo - often characterised by fundamental social inequalities in the communities where he worked. Alongside social investigation and social action, concientisation, or radical education reform, are the key ingredients in his work. The education process is reciprocal and benefits both the researcher and the participants. In the Freirean tradition, research has thus the function of critical inquiry in order to promote radical democracy.

Marxist theory with its focus on the creation of a fairer and more equal society, and the ambition to improve the lives of disadvantaged people, inevitably became one of the core theoretical building blocks of participatory and action research practice. Despite the misappropriation of scientific Marxist theory by would-be socialist and communist leaders, Marxist theory with its vision of a fairer society enjoys continued academic influence among participatory and action research practitioners.

The final main theoretical building block for participatory research practice is critical feminism. Its main contribution to participatory and collaborative research practice is the exposure of the failure of conventional research methods to capture the voice of women and other disadvantaged groups of people. One of the core insights from feminism is that science is not ‘independent of its practitioners, their actions, their aspirations, and their culture; nor is it always separate from the actions of non-scientific actors or institutions’ Morawski (2001, p. 59). Morawski proposes that a more participatory and collaborative research practice in which participants are actively involved in the research will help address subjectivity and reveal power relations in a research project. Participatory and collaborative practice therefore provides a useful framework for research with all marginalised or minority groups.

What unites the four theoretical contributions and is key to participatory research practice is that they all move beyond critiquing the status quo and are focused on transformative action with an emphasis on the social marginalised and disadvantaged (Figure 1).

Figure 1:

Theoretical contributions to participatory methods

Over the years, participatory research approaches have diversified. Some are used very broadly and across disciplines, such as PAR, community-based participatory research CBPR), photovoice, participatory arts-based approaches or participatory evaluations whilst others are more closely associated with particular subject areas or disciplines, such as participatory rural appraisal (PRA), user-led research, participatory organisational research (POR) or action science and citizen science. Rights-based participatory approaches are particularly widely used with participants with disabilities, but also with children and young people, and this is what we will turn to now. We acknowledge at this point the considerable contribution that the fields of sociology of childhood and childhood studies have made to this discourse (e.g. Baraldi & Cockburn (eds) 2018; James, Jenks & Prout, 1998; Qvortrup, J., Bardy, M., Sgritta, G., & Wintersberger, H. 1994).

3 Children’s rights and participatory research with children and young people

Not all participatory research projects with children and young people draw on a rights-based rationale, nor do all research projects with a focus on children’s rights use participatory approaches, but the Lundy Model of participation (Lundy, 2007) has been hugely influential on the way participatory research with children and young people is conceptualised and connected to the children’s rights agenda. However, as this article is published less than a year after the 30th anniversary of the United Nations’ Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC), it would be remiss not to remind ourselves of the origins and ambitions of the children’s rights agenda. The UNCRC was signed on 20th November 1989. The Convention has been adopted and ratified by all countries bare one (the USA) and sets out legally binding rights for every child. The UNCRC replaced and advanced the Declaration of the Rights of the Child, signed by the United Nations in 1959, which itself was an extended version of the original Declaration published by the International Save the Children Union and adopted by the League of Nations in 1924.

The original Declaration of the Rights of the Child initially focused on immediate and basic needs of children, such as giving the child the means for a ‘normal development’ [original wording]; the tackling of hunger, the protection from exploitation, but also the right to develop his or her talents. The UNCRC protected and extended these rights, namely with the notion of children’s and young people’s right to have some say when it comes to decisions that affect them. This can be seen as an acknowledgment of the agency that children and young people have when it comes to making decisions about their own lives. Article 12 refers to children’s right to express their views freely in all matters affecting them, and it states that these views must be given due weight in accordance with the child’s age and maturity when making decisions about a child. Article 13 states that children have the right to freedom of expression and the freedom to seek, receive and impart information.

Thus, whilst the children’s rights discourse is by no means new, the last 20 years or so have seen an institutionalisation of children’s rights, supported by the establishment of children’s rights commissioners in many countries. This has raised the profile of the children’s rights framework which has had a significant effect on how much of the research on and with children and young people is framed. It is therefore no coincidence that Articles 12 and 13 of the UNCRC are frequently quoted as rationale for involving children and young people as active participants, for example as co- or peer researchers, ie research collaborators in some or all stages of a research study. Borland et al. (2001) argue that we have seen a movement from research on children to research with children and research empowering children.

4 Ethical issues in participatory research with children and young people

Principally, participatory research practice with children and young people does not necessarily differ in its ambition or approach from that with adults just because it involves children and young people. However, in addition to the conventional ethical issues we face in any research project involving human participants (such as informed consent, confidentiality and data protection), the status of the children as minors adds some legal and ethical barriers that need to be addressed.

The first main issue is that additional layers of consent and permissions may be required from parents or guardians, but also from institutional gatekeepers, such as schools, care homes, youth projects etc. So, children who are under the legal age of consent and those who are approached and recruited through institutions often cannot themselves decide whether or not they want to take part in research. The legal framework of the age of consent, which basically puts a barrier in place for children under a certain age to make some decisions about their lives has been criticised as an impediment for children’s agency. The counter argument is that the legal age of consent protects children from potentially abusive relationships. However, one of the main criticisms is that these age limitations are sometimes quite artificial and contradictory. They also vary between and within countries and cultural contexts.

When it comes to research with children and young people, the reality is that children under the respective age of consent are subject to gatekeeper consent and sometimes gatekeeper selection. Some research projects are of course initiated by children and young people themselves, but that usually happens when children and young people are already organised in an institutional context, for example as service users, and there is a level of support and encouragement available. Nonetheless, issues around consent and agency should be explored in all circumstances. How well do the activists represent their communities and their peers? Is individual consent sufficient, or do the groups on behalf of which the young activists speak or research also need to consent to the study? Is the study going to be of benefit for the whole community or just for the activists/co-researchers? What are the physical and emotional risks involved in being a co-researcher or participant in a study? These questions are very closely related to the other main issue in participatory research practice with children and young people, namely the need to consider their safe-guarding. Mechanisms must be put in place to protect children and young people for the duration of a research project, but also afterwards.

In participatory research practice, another important ethical issue relates to the participatory approach as such and how genuinely we want children and young people to make a real contribution to the way a research project is organised and run. Tokenism has for a long time been the main charge against researchers who claimed a participatory rationale, but did not really take children’s and young people’s opinions seriously. These are studies in which children are often little more than ornaments to give the study weight and credibility. However, recently Lundy (2018) has spoken out ‘in defence of tokenism’, arguing that there can be positive learning for children and young people even in tokenistic participatory efforts, but good ethical practice is certainly clarity about contributions and the management of realistic expectations from the start and throughout a study.

In studies which are not initiated by children and young people themselves, the rationale or purpose for taking a participatory approach should therefore be made transparent. It should be clear how this furthers the research objective. If it does not, it does not rule out a participatory approach, but it should be acknowledged. The core question is the how much participation we can and want to afford, and to what extent the interpretive power remains in professional researchers’ hands. The level of participation will often depend on the resources, including the time available for a project, but may also be influenced by principal convictions, for example the view that children have a right to be consulted and listened to in matters that affect their lives.

Group dynamics and power relations between senior researchers and young co-researchers on the one hand, and co-researchers and research participants on the other, have to be managed. The challenge is to develop and maintain positive reciprocal non-hierarchical relationships with the young co-researchers and to keep a good balance between closeness and good rapport and distance.

One of the main benefits of working with young co-researchers is often that they are peers of the research participants. One of the challenges is therefore that they need to continue to communicate with their peers as equals in order to realise the benefits of a participatory approach, but at the same time, young researchers need to fulfil roles of professional researchers (such as making contributions to data collection and analysis and the dissemination of results, which may include the engagement with policy and decision makers). The researcher-participant role conflation (Durham Community Research Team, 2011) that has been discussed for participatory and in particular participatory ethnographic research, does of course also apply to young researchers. Children and young people often initiate research projects or volunteer to be co-researchers on research studies because they feel particularly passionate about a research topic. They may already be activists in this area, for example in a community organisation or local youth council. Or, they may be service users, such as users of youth services, as in some of the examples in our research discussed below, and they may want to make changes to the services they receive. As with adult activists and co-researchers, this means that issues such as over-rapport (sometimes also referred to as ‘going native’), and participants’ expectations have to be managed.

Being a researcher and activist at the same time may have implications for the rigour and potential bias with which data is being collected and results interpreted and presented. Again, just as with adults, the challenge is to discuss with young co-researchers and service users the importance about being clear about their positionality and open about the perspective that they take in the research process. Senior researchers working with children and young people as co-researchers have a responsibility to help the children and young people to be organised in their research, but they are also supervisors and carers who have to be aware of the potential risks that the co-researchers and participants may be exposed to. One of these risks is related to activism and publicity in connection with a research project. Being in the public domain as an activist or lobbyist, or demanding change as a service user, carries the risks of being exposed, exploited, abused or attacked both in the virtual online and in the physical world.

Bengtsson and Mølholt (2016) therefore propose to identify ‘ethical red flags’ from the very start, and this is especially important in research with children and young people. Related to the question of the ‘red flags’ is a core question in terms of children’s and young people’s rights, namely the issue of their ‘best interests’. The UNCRC (Article 3) demands that ‘the best interests of the child’ should be a primary consideration in all actions adults take concerning children. However, as Archard and Skivenes (2009) have shown this is not necessarily a very straight forward process. They argue that it is not always in a child’s best interest to hear a child’s view and that a child’s view may in fact be contradictory to his or her own interests. It is also not always clear who makes the judgement of ‘best interest’ and on what basis this is made. The authors point out that steps need to be taken to ensure that the views expressed by participants are genuinely their views.

As this section has shown, there are some significant challenges in the organisation of participatory research with children and young people. Boyden and Ennew (1997) appropriately remind us that ‘no research is inherently participatory’, and that real efforts have to be made to take children and young people’s views and contributions in a research study serious.

5 Stages in Participatory Research Processes

We will now report from some of our co-produced research processes in which young people as service users have been actively involved. The discussion is going to follow typical problems in all participatory research stages: from establishing research and finding a communicative space to collecting and analyzing data and finally reporting outcomes and insights.

In our "Traveling Youth Research Group" (RJFG), we collaborated with a group of 12 young people and three educators (Ackermann and Robin 2017). In the study, we explored the participation opportunities for looked-after children and adolescents. The group undertook a three-day research trip during which they visited various residential settings run by a child and youth welfare service. The second project we are referring to explored the experiences of service users in the child welfare system. In this study we collaborated with children, young people and their parents in a photo voice project (Ackermann and Robin 2018).

5.1 Establishing the research study and a communicative space

Typically, the first challenge in participatory research with young service users is the establishment of contact with those who have experiences that are relevant for the research project and who are interested in participating in the research.[1] As in other fields of social research, accessing the field should be regarded as a complex active and interactive stage of the research process (Wolff 2012). If access to the field is provided via social services organisations, which is often the case in research with service users, some constraints may have to be dealt with.

First, the very initiation of the research project itself and the desire to find out more about service users may trigger apprehension and resistance within the organisation. Participatory research with users often encounters organisational cultures and "practical ideologies" (Klatetzki, 1993) in which skills and competencies are attributed to the professionals and vulnerability to the clients. In these contexts, it may be hard to comprehend, or it may even be seen as a provocation, that service users could become co-researchers in research projects.

Participatory research approaches question the systematic and institutionalised privileges of expert knowledge. The involvement of service users challenges professional autonomy, as participatory approaches try to open the “black box” of professional practice. Thus, from the perspective of the organisational institutions these approaches may be seen as uninvited inspections. It is therefore necessary to anticipate a level of gatekeeper resistance due to a perceived need to defend themselves against "unwanted or unfamiliar intentions" (Wolff 2012, p. 343).

Second, a decision has to be made about who the most suitable co-researchers or 'peer researchers' are, and who should be selected to take part in the study. A core question in this respect is: "Who decides who is allowed to participate?" When accessing the field through social services organisations, the pre-selection of co-researchers is often in the hands of gatekeepers of the relevant organisation who are in the position to enable or disable contact to more junior staff members and service users. The problem is that certain groups of users could be persuaded or selected to participate because they are expected to present the organisation in a favorable light (Ackermann, 2019). Participatory research is located in contested fields of knowledge production and must therefore position itself in order to avoid a reproduction of power imbalance. However, sometimes participants are selected because they are considered most adult-like or most mature, so Archard and Skiveness (2009) remind us that we need to ask the question who decides when a participant is ‘mature’ enough to give consent and on what basis? Who decides how ‘maturity’ looks like and how it manifests itself? What is the standard of maturity and competency against which this is judged and by whom. As a consequence of the selection process, sometimes other non-mainstream views are underrepresented. It therefore makes sense to include not only easily accessible, but also marginalised actors in the research in order to represent a diverse as possible range of knowledge, interests, and perspectives in the research group. One possible strategy for this is to apply certain selection criteria to ensure that, for example, young people of different ages, gender, and status are included in a study, including young people who may be perceived a “difficult” service users. In addition, it might be helpful to define appropriate criteria for co-researchers and to communicate these criteria to respective gatekeepers. Another approach might be to ask study participants themselves to invite other participants into the study, who, are known to hold other, perhaps contradictory or conflicting views. Neither strategy does circumvent the problem of access completely, but they may increase the diversity of voices represented in the research process.

Perhaps the main challenge is to establish a "communicative space" in which all aspects of the research process can be dealt with (Kemmis et al., 2014, pp. 90f.; Wicks and Reason 2009, p. 258). This communicative space is central for participatory research. In the spirit of deliberative democracy, it should afford all participants the ability to make important decisions concerning the research process (Kemmis and McTaggart, 2007). Moreover, it assures that the whole group is actively involved in all phases of the research process from identifying the research interest, collecting the data, to analyzing and disseminating the results. This requires the capacity to critically assess group conflicts and their impact on the work processes. Thus, senior researchers should pay sufficient attention to aspects of the group dynamic especially in the initial phase of the research (Bergold and Thomas, 2010, p. 338). In order to support the establishment of a conducive team work atmosphere, the senior researchers’ role is to support the team building processes, for example by facilitating participants to get to know each other on a personal level and to share their research interests. Icebreaking activities that could be used during inaugural group sessions include mutual interviews and interactive games. The expectations of the co-researching service users should be discussed at an early stage of a project. In our experience, it is important to agree in the group suitable means of communication as well as mechanisms for how confidentiality can be maintained. It is also a good idea is to discuss very early on in a project co-researchers’ own ambitions and the contributions they are willing to make. This can be done by exploring questions such as: why they chose to participate; what changes they would like to see; why they think we involve co-researchers in research studies; what they feel young researchers and services users can contribute to research that academic researchers cannot offer; and what expectations senior researchers and co-researchers have from each other.

Whilst the desire to generate change in their organisation or community is often the main motivation for co-researchers and services users to participate in research, this ability to bring about change is often restricted by the very institutional context in which young people operate. Thus, whilst the senior researchers should encourage co-researchers and services users to become actively involved in the research, they also should, in our opinion, help to establish realistic expectations in relation to achievable social change.

An important aspect in the establishment of a research team is the formulation of common research interests (Kemmis et al., 2014, pp. 95f.). Co-researching users, who usually have not studied, or have no prior knowledge of, empirical social research, bring a different kind of knowledge to the project. In order to facilitate constructive team discussions and meaningful research planning, it is therefore sensible to establish a basic common platform from which the project can be organised. This may involve some initial research skills training and a first open exploration of the research topic. Possibilities and limitations of empirical social research must be considered in an accessible way as part of the team formation process. If the research design itself is developed in a collaborative way, the research team should decide which research methods are most suitable to answer the research questions. Research team residentials can go a long way to create a positive team spirit as well. If resources are available for remunerations, research contracts for co-researchers could be prepared and signed. These remuneration could be individual payments or vouchers for co-researchers, but also group awards, celebrations fun events (such as parties, cinema visits, etc.).

In contrast to conventional qualitative research approaches, more attention needs to be paid to the suitability of research methods. The chosen methods do not only have to be adequate for the study’s research objectives but also suitable for the co-researches themselves.

Due to the mechanisms which are used to allocate funding for research, especially in the context of third-sector research funding, collaborative approaches to developing a research design can be challenging. Typically, resources are obtained before the research study commences. This normally requires the prior submission of detailed research proposals, containing detailed descriptions of research questions and designs including descriptions of the intended use of methods (Bergold and Thomas, 2012, Abs. 82, 86; Ackermann and Robin, 2017, p. 98). This often leaves very little room for the participatory development of a research design. One strategy to bypass this problem is to emphasize the explorative character of the planned project at the application stage, and the importance of retaining some flexibility for decision making by the research team in relation to the research design.

Some of these challenges in participatory project planning and design will now be illustrated using an example from our own work. In a study conducted with a group of young people and social workers, the funding body – an organization managing a number of care facilities - had a predetermined research interest, namely to explore how conditions for participation of young people can be shaped in their facilities (Ackermann and Robin, 2017, p. 98). Thus, we initially developed a common understanding of what participation in child welfare institutions might mean. With this brief in mind, the young co-researchers identified three areas of research interest: some young people examined the reality of participation opportunities in the everyday life of residential groups. A second group explored the involvement of young people in matters of occupational careers. The third group focused on participation of young people within the context of health issues. It soon became apparent that the young people were in fact trying to bring about actual changes for themselves and other young people: some of the co-researchers were pushing for more say in the choice of leisure time activities while others were interested in more participation rights in the decision making with regard to their school and occupational careers. Another central issue for the co-researchers was also the improvement in the provision of adequate support and holistic information in relation to self-injury and the use psychopharmaca and their symptoms (Ackermann and Robin, 2017, p. 61ff.). By putting these important issues on the agenda of the research project, the young co-researchers sensitized us for aspects of the research subject that we had not been aware of and that we could not have anticipated. Thus, the collaborative development of research priorities with the co-researchers was a crucial step that insured that the co-researchers’ real-world experiences and knowledge informed the study design and subsequently the research report alongside the academic input.

5.2 Collecting and analyzing data

Participatory research approaches aspire to data collection not about users, but with users. In principle, all forms of data collection from the canon of empirical research methods can also be used in participatory research projects (Bergold and Thomas, 2010, p. 338). Users can for example participate in the design and fieldwork of small or large scale surveys, they can conduct interviews or observations or help compile and analyze documents. However, unlike in conventional research, the choice of research methods must not only be informed by the research question(s) and their appropriateness for the researched subject area, but it should also take into account the research context and capacity and skills of co-researchers (Bergold and Thomas 2010, p. 340). Generally, however, the explorative orientation of qualitative research methodologies may fit better with the nature of participatory research processes than the standardized methods of quantitative social research.

If the research team decides that co-researchers will contribute to the data collection, for example, by independently conducting interviews or observations, this typically requires a preparatory phase. The task of the senior researchers (or experienced co-researches) is to facilitate some research methods training and knowledge exchange in the research team. For example, it should be addressed how data collection should be carried out in practice using what specific techniques, and what research ethical issues should be taken into account when undertaking fieldwork (see also above).

The joint development of data collection tools with the co-researchers ensures that the research interests of the co-researchers or service users are taken seriously in this phase of research, that they make a meaningful contribution, and that the research tools are reflective of the young people’s and service users’ life worlds. For example, co-researchers can help to formulate questions that correspond with the language used by young people in the field of research. The co-researchers in one of our projects decided to conduct peer-led interviews and developed the research tools themselves (Ackermann and Robin, 2017, p. 29f.). Thus, together with the co-researchers, we discussed possible forms of questioning in interviews and piloted interview techniques using role-playing games. Maybe more importantly, we collaboratively developed interview guides in which we included questions posed by the young researchers using their own language.

In the participatory development of research instruments, differences and tensions between life-worldly and academic rationalities might emerge. For example, young people in one of our own research projects proposed to use interview questions that were at odds with the open character of qualitative research. Young people formulated closed interview questions which senior researchers initially rejected as unsuitable and non-narrative inducing. Eventually, after discussion in the research team, we agreed to compromise and included both closed and open questions in the interview schedule. Perhaps this is the reason why the co-researchers were then able to conduct interviews in a fashion that seemed to be close to the communication style in their lifeworld. The data collected by this questioning technique did not have the depth that would be expected in the context of qualitative interview studies. At first, we therefore considered the data as inferior, as it did not contain substantial narrative passages, but rather mirrored every-day discussions between young people. It took us a while to recognise that this data was nevertheless (or for that very reason) a very fruitful basis for our data analysis, and the interview data was then treated as valuable data rather than as worthless or inferior. For further research with service users we learnt from this that it is a good idea when collaborating with co-researchers in the collection of data to appreciate the differences in the academic and life-worldly perspectives, and to permit the convergence of these two ways of knowing.

In participatory research data collection and analysis are closely intertwined in spiral or iterative processes which are typical for qualitative explorative research (Kemmis and McTaggart 2007, pp. 278f, Charmaz 2014). In the "communicative space" (Kemmis et al. 2014, pp. 90f; Kemmis and McTaggart 2007) of the research team, discourse takes place on the subject of research. These processes of sense-making themselves represent part of the analytic work in a research study and are component of the evidence that contributes to insights on the research subject at individual but also of shared team level. Audio recordings of these group discussions and negotiations themselves contain a wealth of data. The transcribed recordings of these discussions can be used as material within the research team’s analytical considerations. Still, also in the selection of data collecting methods power relations between adult and infant co-researchers should be considered. Morrow and Richards (2007) suggest to use multiple, creative ways of data collection which fit the needs of the co-researches order and advocate to coproduce data “in the relation between researcher and researched” (p. 101).

Thus, the data analysis in participatory research processes should not just be understood as a technical procedure, but rather as a shared and discursive reflection on the subject of research in the research team (von Unger 2014, p. 62). Due to the different types of knowledge and various levels of time resources that senior researchers and co-researchers bring to the team, it is unsurprising that a participatory approach to data analysis can be challenging. Young co-researchers and service users are typically inexperienced in analyzing empirical research data. Often, they also have multiple other obligations (e.g., family, friends, work, or school). It is therefore sometimes necessary to take a pragmatic approach and use less complex data analysis techniques with the co- researchers (Bergold and Thomas, 2010, p. 341).

Whilst it is useful and enriching if co-researchers and service users relate to their own biographical experiences in the discussions about the collected data, some may find it difficult to look beyond their own experiences and to relate to the perspectives and experiences of others. Nevertheless, the contribution of co-researchers and service users to the data analysis must not be undervalued. The plurality of perspectives expressed by co-researchers provides more diverse voices and interpretations of the collected material. Sometimes, this reveals different dimensions or aspects to the data that were not considered before. The insider knowledge of the co-researchers therefore makes the research processes and practices more insightful and coherent and sometimes the data plausible and accessible in the first place. The plurality of perspectives of the group members facilitates various readings of the empirical data supporting more diverse and considerate interpretations of issues and practices in the field of research. Nevertheless, it is sometimes difficult for the young co-researchers (as for more experienced researchers) to differentiate their own needs, fears and experiences from more general insights generated through data collection as part of a research process with a clear audit trail. The involvement of co-researchers and service users recruited from the context in which the study takes place, therefore always carries a certain risk that conclusions on the findings of a study are drawn prematurely. One way to ameliorate the data analysis process with co-researchers and service users is therefore to apply techniques such as the estrangement or distancing effect famously developed and used in Brecht’s theater to emotionally distance the audience from a topic with the aim to help them to understand core issues and problematics. The idea in the analysis work with service users and co-researchers is to attune them to a meta-perspective on the research topic without at the same time to dismiss their personal experiences as irrelevant.

Methodologically, this kind of analysis undertaken in a research team lends itself well to a procedure that is based on the paradigm of grounded theory. The initial open, or line-by-line, coding (Charmaz 2014, pp. 50-53, Strauss and Corbin, 1990) can be undertaken in a group context, where the analysis benefits from the group's many voices in interpretation of the texts. The following selective and axial coding can also be undertaken in a group context in order to extract the thematic and analytical content from the research data (Ackermann and Robin, 2017, p. 37f.). It can also be seen to as a futher step to equal power imbalance in the research group itself (Morrison and Richards, 2007).

5.3 Capturing and disseminating research results

At the end of a research project the task is to distil and disseminate the research findings. This should also ideally be done in collaboration with the co-researchers. Decisions have to be taken with regard to the target audience of research outputs and the respective appropriate formats of the outputs (von Unger, 2014, p. 67). A final project report probably represents a format, that most closely resembles the standard and requirements of an academic publication. However, if political representatives or other decision-makers are to be addressed, it may be more appropriate to draft condensed project report versions with clear recommendations for action or demands for change. Photographic images, comics and videos can be good tools to make the research results available to a wider audience, including other service users. Visual representations of study results can also be utilized to illustrate results when they are communicated to politicians or other decision makers (von Unger, 2014, pp. 69f.; Ackermann and Robin, 2018).

When it comes to giving presentations on the research findings, the question arises to what extent service users can participate in this. One challenge is that service users have different language practices and that public speaking in front of an audience is not usually something they are accustomed to. Nevertheless, the active involvement of service users in presentations, for example to academic audiences may be useful, as service users are the experts in their own lives and are often best at communicating first-hand experience and telling their own story, even though this does not protect them from being misunderstood or being perceived as being ‘wrong’ (Kemmis et al. 2014, p. 188). Nevertheless, a collaboratively delivered presentation can help link the perspectives of academics with those of the lived experiences of service users.

One challenge in the planning of joint presentations of research findings with service users and co-researchers is to ensure that they remain active agents in this process who can make use of their skills, thus and facilitating an enriching experience for them and the audiences. Co-researchers can, for example, deliver smaller or larger parts of presentations depending on their skills and confidence. It is important to ensure that co-researchers/service users do not end up in ‘on display’ like in a cabinet of curiosities. This could happen when service users are interrogated by curious professionals or academics about their lived experiences rather than about the generated research findings and conclusions. One option is to prevent this from happening is the incorporation of short videos into the presentations in order to allow service user voices to be heard without having to facilitate direct or interactive contact with the audience. Short dramatisations and performances are also ideal tools that can create safe spaces for service users from which emotional and personal aspects of a research topic can be communicated to an audience in an accessible way. Occasionally, in the most far-reaching participatory mode of communicating research results, co-researchers take ownership of the whole dissemination strategy and communicate research findings to decision-makers or academic audiences without any guidance or input from senior researchers. A pitfall of participatory research with young people and service users could be seen in a possible scandalization of the research as the study results might reveal participants’ vulnerabilities. Also, service users and young people might not always be socially equipped to defend their point of view or to correct misunderstandings in front of an audience. This should be reflected on before and during the dissemination period in order to protect the participants also in this stage of the research process (Morrow and Richards, 2007, p. 102).

In addition to any data collected and any social changes that might have been achieved as a result of the research project, the capacity building and learning processes themselves should be considered as important outcome of participatory research projects (Kemmis et al., 2014, pp. 12f.). The experiences of being involved in a participatory research project itself often generates change in co-researchers’ and service users’ personal or professional relationships, even without having to devise concrete actions plans for this (Kemmis et al., 2014, pp. 100f.). Within a research project, co-researchers and service users are encouraged to look at their own daily experiences and routines from an elevated external position. This allows the co-researchers to understand their experiences as service users differently. They might even gain new insights and impulses for individual action schemes, which can have positive effects on their own biographical trajectories and those of their communities (Burns and Schubotz, 2009).

In our experience many young people benefit from the experience of being co-researchers and apply their new competencies and skills in their daily lives. For example, they may benefit from the experience of public speaking and representing their interests in front of groups of their peers or adults. They also use their newly gained knowledge about institutional contexts to empower themselves and initiate changes in their institutions (Ackermann and Robin, 2017). The research partners (such as community organisations, schools, care homes etc.) can also become multipliers as they transfer and translate the research perspectives, experiences and outcomes into their life worlds or professional practices. Participatory research can lead to improved self-organization and advocacy work among co-researchers, service users and their communities. For example, in one of our research projects, as a result of their engagement in participatory research, care leavers in France and Germany established service users’ associations that represent their interests and are committed to initiating further social changes (see https://www.careleaver.de/).

6 Conclusion

Participatory research approaches and user-led research with young people aim to elevate study participants and service users respectively to the status of active actors who have a more pro-active input in the research and service development and delivery, and who increase their status in that process. Co-researchers and service users in collaborative research approaches are regarded and treated as active knowledge holders rather than passive information providers. In participatory approaches, research strategies and agendas are therefore developed in collaboration between senior researchers and co-researchers. As we have seen, such processes involve greater efforts, as the necessary conditions for an effective co-production approach involving service users often have to be created first. This involves the identification of suitable, engaged co-researchers and the exploration of their respective competences as well as the establishment of a “communicative space” in which open discussions in the research team can safely take place. User-led collaborative research approaches therefore require sufficient resources as well as flexibility and openness among involved senior researchers with regard to their own role and role interpretation. This researcher-activist role conflation requires them to assume different roles, depending on the requirements at different stages of a project, including the roles of educators, conflict mediators, lecturers, organizers, or analytic scientists (Bergold and Thomas, 2012, para. 44).

We maintain that there are strong arguments for collaborative research involving service users. Participatory approaches in social research emphasize voluntariness, increase service users’ influence on the research process, provide space for the articulation of their own interests, and therefore closely relate to the lifeworld experience of service users (Ackermann and Robin, 2017, p. 20). The involvement of service users as co-researchers gives more control to the participants, as the decision making on research design and agenda is part of the communicative space of the research group. Conducting research together with young people as co-researchers can also bring science closer to the real concerns of young service users, and it is therefore more directly focused on social change in the field of research. Co-production approaches do not only make participants’ voices more audible, but they emphasize their agency (Rodríguez and Brown, 2009). Collaborative research approaches help develop self-confidence among service user groups and they can also endorse service users’ interests as justified (Hirschfeld, 1999, p. 80) and may thereby initiate social changes in the field of research. Participatory research projects still attempt to generate academic knowledge, but they also seek social change in the field of research and for the participants themselves (Schubotz, 2019). Unlike conventional research approaches, they can therefore yield more direct benefits for the services users themselves.

Participatory approaches to social research value the service users' knowledge. Moreover, they are confronting conventional academic approaches that claim to have an objective insight, by using “the god trick of seeing everything from nowhere” (Harraway, 1988, 581). Participatory approaches go beyond conventional research as they treat service users not only as providers of information, but as experts the ability to examine their own lifeworld. Participatory research supports the view that service users are able to be part of research processes; they can of course reflect on their own lives and those of their peers. Young people and other services users have the capacity and skills to access their own knowledge and, therefore, dare to better defend their interests. Nonetheless, participatory research processes are also fraud with power imbalances between adults and young people, between researchers and services users, which should be reflected in every stage of the research (Morrow and Richards, 2007, pp. 101 f.; Esser and Sitter, 2018).

Academic researchers who are interested in the perspectives of young people as service users will continue to use the entire spectrum of social research methods. However, participatory research practice places more weight on the voices and agency of young service users than conventional research approaches as they focus on actual active participation rather than just involvement in research. Even though the ambition for an all-encompassing participatory approach throughout all stages of a research study cannot always be realized, it is good practice to be transparent about opportunities for and limitations of participatory practice to both study participants and the audience of the research outputs (Bahls et al., 2016).

It is important to keep in mind, as we discussed at the start of our contribution, that participatory research practice originally emerged in response to the failure of conventional research to bring about action and positive social change for the people who were simply the ‘objects‘ of the respective studies. Forty years after the participatory turn in social research and thirty years after the signing of the UNCRC, children and young people grow up in a world which is more unequal than before and in which it becomes increasingly clear that the way we live and exploit available resources is not only unsustainable but in fact life-threatening. The fact that children and young people have started to very publicly take initiative to demand changes shows that they realise that these threats are real and that they and future generations are going to be at the receiving end of our unsustainable lifestyle. Unfortunately, the promise of social change via participatory research practice has so far remained largely unfulfilled, certainly at macro level. The immediate task must therefore be to up-scale participatory research efforts to address these immediate and growing issues of inequality, exclusion and sustainability at macro-societal level.

References:

Ackermann, T. (2020). Nutzer*innen als Co-Forschende?! Prozess, Herausforderungen und Strategien partizipativer Forschungsansätze. In A. van Rießen, & K. Jepkens (Eds.), Nutzen, Nicht-Nutzen und Nutzung Sozialer Arbeit: Theoretische Perspektiven und empirische Erkenntnisse subjektorientierter Forschungsperspektiven (p. 89–103). Wiesbaden: Springer.

Ackermann, T., & Robin, P. (2017). Partizipation gemeinsam erforschen: Die Reisende Jugendlichen-Forschungsgruppe (RJFG); ein Peer Research-Projekt in der Heimerziehung. Hannover: EREV.

Ackermann, T., & Robin, P. (2018). Die Perspektive von Kindern und Eltern in der Kinder- und Jugendhilfe: Zwischen Entmutigung und Wieder-Erstarken. URN: urn:nbn:de:0111-pedocs-174525; http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0111-pedocs-17452.

Archard, D., & Skivenes, M. (2009). Balancing a Child’s Best Interests and a A Child’s Views. The International Journal of Children’s Rights, 17(1), 1-21.

Bahls, C. (et al.) (2016). Partizipative Forschung: Memorandum. https://www.khsb-berlin.de/fileadmin/user_upload/ Partizipative_Forschung_ zum_Thema_sexualisierter_Gewalt_-_Memorandum.pdf.

Baraldi, C., & Cockburn, T. (eds.) (2018). Theorising Childhood Citizenship, Rights and Participation. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

Bengtsson, T. T., & Mølholt, A. K. (2016). Keeping you Close at a Distance: Keeping You Close at a Distance: Ethical Challenges When Following Young People in Vulnerable Life Situations. Young, 24(4), 359-375.

Bergold, J., & Thomas, S. (2010). Partizipative Forschung. In G. Mey & K. Mruck (Eds.), Handbuch Qualitative Forschung in der Psychologie (pp. 333–344). Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Bergold, J., & Thomas, S. (2012). Partizipative Forschungsmethoden: Ein methodischer Ansatz in Bewegung. Forum Qualitative Research, 13.

Bernhard, A. (2006). Antonio Gramscis Verständnis von Bildung und Erziehung. UTOPIE Kreativ, (183), 10–22.

Borland, M., Hill, M. Laybourne, A., & Stafford, A. et al. (2001). Improving Consultation with Children and Young People in Relevant Aspects of Policy-Making and Legislation in Scotland. Edinburgh: Scottish Parliament.

Boyden, J. & Ennew, J. (1997). Children in Focus: A Manual for Participatory Research with Children. Stockholm. Rädda Barnen.

Breuer, F., Muckel, P., & Dieris, B. (2010). Reflexive Grounded Theory: Eine Einführung für die Forschungspraxis. Wiesbaden: VS Verl. für Sozialwissenschaften.

Burns, S., & Schubotz, D. (2009). Demonstrating the Merits of the Peer Research Process: A Northern Ireland Case Study. Field Methods, 21, 309–326.

Charmaz, K. (2014). Constructing Grounded Theory. London: SAGE.

Durham Community Research Team (2011). Community-based Participatory Research: Ethical Challenges. Durham: Centre for Social Justice and Community Action, Durham University.

Eßer, F., & Sitter, M. (2020). Ethical Symmetry in Participative Research with Children. Forum: Qualitative Social Research, (19), 3.

Eylon, D. (1998). Understanding Empowerment and Resolving Its Paradox: Lessons from Mary Parker Follett. Journal of Management History, 4(1), 16-28.

Freire, P. (1971). Pedagogy of the Oppressed, (trans. M. B. Ramos, Trans.). New York: Seabury Press.

Graßhoff, G. (eds.). (2013). Adressaten, Nutzer, Agency: Akteursbezogene Forschungsperspektiven in der Sozialen Arbeit. Wiesbaden: Springer.

Hall, B. L. (1975). Participatory Research: An Approach for Change. Convergence, 8(2): 24.

Hirschfeld, U. (1999). Soziale Arbeit in hegemonietheoretischer Sicht. Gramscis Beitrag zur politischen Bildung Sozialer Arbeit. Forum Kritische Psychologie, (40), 66–91.

Homfeldt, H. G., Schröer, W., & Schweppe, C. (2008). Vom Adressaten zum Akteur: Soziale Arbeit und Agency. Opladen: Budrich.

James, A., Jenks, C. & Prout, A. (1998). Theorizing Childhood. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Kemmis, S., & McTaggart, R. (2007). Participatory Action Research: Communicative Action and the Public Sphere. In N. K. Denzin und Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Strategies of qualitative inquiry (pp. 271–330). Los Angeles: SAGE.

Kemmis, S., McTaggart, R., & Nixon, R. (2014). The Action Research Planner: Doing Critical Participatory Action Research. Singapore, Heidelberg, New York, Dordrecht, London: Springer.

Klatetzki, T. (1993). Wissen, was man tut: Professionalität als organisationskulturelles System: eine ethnographische Interpretation. Bielefeld: Böllert KT-Verl.

Klatetzki, T. (2010). Soziale personenbezogene Dienstleistungsorganisationen als soziokulturelle Solidaritäten. In T. Klatetzki (Eds.), Soziale personenbezogene Dienstleistungsorganisationen.: Soziologische Perspektiven (pp. 199–239). Wiesbaden: VS Verl. für Sozialwissenschaften.

Lewin, K. (1946). Action Research and Minority Problems. Journal of Social Issues, 2(4), 34–46.

Lundy, L. (2007). ‘Voice’ Is Not Enough: Conceptualising Article 12 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. British Educational Research Journal, 33 (6), 927-942.

Lundy, L. (2018). In Defence of Tokenism? Implementing Children’s Right to Participate in Collective Decision-Making. Childhood, 25(3), 340–354.

Morawski, J. (2001). Feminist Research Methods: Bringing Culture to Science. In D. Tolman, D. and M. Brydon-Miller, M. (eds.) From Subjects to Subjectivities. A Handbook of Interpretive and Participatory Methods (pp. 56–-75). New York: New York University Press.

Morrow, V., & Richards, M. (2007). The Ethics of Social Research with Children: An Overview. Children & Society, 10(2), 90–105.

Qvortrup, J., Bardy, M., Sgritta, G., & Wintersberger, H. (1994). Childhood matters: Social theory, practice and politics. Aldershot: Avebury

Reason, P., & Bradbury, H. (2001). Introduction: Inquiry and Participation in Search of a World Worthy of Human Aspiration. In P. Reason & H. Bradbury (Eds.), Handbook of Action Research: Participative Inquiry and Practice (pp. 1–14). SAGE.

Rodríguez, L. F., & Brown, T. M. (2009). From Voice to Agency: Guiding Principles for Participatory Action Research with Youth. New Directions for Youth Development 2009, 123, 19–34.

Schaarschuch, A., & Oelerich, G. (2005). Theoretische Grundlagen und Perspektiven sozialpädagogischer Nutzerforschung. In G. Oelerich & A. Schaarschuch (Eds.), Soziale Dienstleistungen aus Nutzersicht: Zum Gebrauchswert sozialer Arbeit (pp. 9–25). München: Reinhardt.

Schubotz, D. (2019): Participatory research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. M. (1990). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Los Angeles: SAGE.

Susman, G. & Evered, R. (1978). An assessment of the scientific merits of action research. Administrative Science Quarterly, 23, 582-603.

Swantz, M. L. (1975). Research as an Educational Tool for Development. Convergence, 8(2), 44–52.

Unger, H. v. (2014). Partizipative Forschung: Einführung in die Forschungspraxis. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Wicks, P. G., & Reason, P. (2009). Initiating Action Research. Action Research, 7(3), 243–262.

Wolff, S. (2012). Wege ins Feld: Varianten und ihre Folgen für die Beteiligten und die Forschung. In U. Flick, E. v. Kardorff, & I. Steinke (Eds.), Qualitative Forschung: Ein Handbuch (pp. 334–349). Reinbek bei Hamburg: Rowohlt.

Author´s Address:

Prof. Dr. Timo Ackermann

Professur für Theorie und Praxis Sozialer Arbeit mit dem Schwerpunkt Kinder-

und Jugendhilfe

Alice Salomon Hochschule Berlin

University of Applied Sciences

Alice-Salomon-Platz 5

12627 Berlin

ackermann@ash-berlin.eu

www.ash-berlin.eu

Author´s

Address:

Dr. Dirk Schubotz

School of Social Sciences, Education and Social Work

Queen’s University Belfast

Belfast BT7 1NN

++44 (0) 28 9097 3947

d.schubotz@qub.ac.uk

www.ark.ac.uk