Youth Employment Mobility – experiencing (un)certainties in Europe

Jan Skrobanek, University of Bergen

Tuba Ardic, Western Norway University of Applied Sciences

Irina Pavlova, Western Norway University of Applied Sciences

1 Introduction

Mobility in general, and young people’s international mobility in particular, has become a popular topic throughout the last 20 years. Many positive aspects are attributed to it, for example it “can be hugely effective in raising a person’s income, health and education prospects”, that it is “a key element of human freedom” and that it “can enhance ‘human development” (Human Development Report Office, 2010, p. 1; UNDP, 2015, p. 1). Based on this positive framing of mobility a range of local, sub- and supranational mobility initiatives have been launched over the last decade. For example, the “Youth on the Move” program was politically approved by the European Commission in 2010, and was followed by the launch of the EU2020 Flagship Initiative ‘Youth on the Move. A Europe 2020 initiative’ (European Union, 2010). The key aim of the initiative was to foster mobility of young people to open options for degree, job, training and entrepreneur movement between the member states of the European Union.

In the case of Norway, the educational- and employment-focused discourse over recent decades has strengthened. In the context of globalisation and internationalisation, educational opportunities and work life perspectives, but also the competition on the educational and labour market, have significantly increased. Due to this, Norwegian politics have turned towards a more proactive support of educational and employment mobility (Utenriksdepartementet, 2008; 2018). For the first time, the Norwegian Government presented a report to the Norwegian Parliament (the Storting), in which internationalisation of Norwegian education is viewed from an overall perspective, which includes almost all levels of education and to some extent employment (Utenriksdepartementet, 2008). This report can be considered an important milestone within the political discourse on youth and internationalisation. Norway's position in the EU is often described as an outsider and insider (NOU 2012:2, 2012). Despite not being a full member of the EU, Norway has become increasingly more closely tied to the EU in the last 30 years. Cooperation has extended to more and more areas, and Norway is equally open to cross-border as well as international mobility and other freedoms of movement as regular EU member states.

In 2017, the European Pillar of Social Rights was signed by the European Parliament, the Council of the European Union and the European Commission. The main aims are to ensure equal opportunities and equal access to the labour market, fair working conditions, and social protection and inclusion. The Norwegian Government’s strategy for cooperation with the EU (2018–2021) demonstrate that the Norwegian Government supports these aims and will help to ensure that the existing rules in this area are updated, further developed, and better enforced (Utenriksdepartementet, 2018).

However, this positive – ideological and legal – view on (youth) mobility is accompanied by growing shifts regarding the socio-cultural and economic parameters of transitions from youth to adulthood in contemporary societies (Côté, 2000; Cresswell, 2006; Furlong & Cartmel, 1997, 2007; Rasborg 2017; Roberts, 2012). As Bauman states life has become a “liquid life, a kind of life that tends to be lived in a liquid modern society” (Bauman, 2007, p. 1). That remains not without consequences for social and system integration (Lockwood, 1964). As Zygmunt Bauman writes:

“First of all, the passage from the ‘solid’ to a ‘liquid’ phase of modernity: that is, into a condition in which social forms (structures that limit individual choices, institutions that guard repetitions of routines, patterns of acceptable behaviour) can no longer (and are not expected) to keep their shape for long, because they decompose and melt faster than the time it takes to cast them, and once they are cast for them to set. Forms, whether already present or only adumbrated, are unlikely to give enough time to solidify, and cannot serve as frames of reference for human actions and long-term life strategies because of their short life expectations …” (Bauman, 2007, p. 1).

This drift has affected both the socio-cultural (Cresswell, 2006, p. 1) and economic arenas (Blossfeld, Klijzing, Mills, & Kurz, 2005, p. 18) and has led to increased risk at an individual, institutional and structural level ( Blossfeld, Klijzing, Mills, & Kurz, 2005; Beck, 1992).

Against this background, transition pathways from youth to adulthood have undergone significant change over the last decades (Bendit & Miranda, 2015; Lorentzen, Bäckman, Ilmakunnas, & Kauppinen, 2018; Sironi, 2018; Walther, 2006). It has become widely agreed that former stable trajectories in the transition to adulthood have become prolonged, fragmented, fragile and contingent (Roberts, 2012, p. 485). Today’s young people face higher risks of being captured in states of “arrested adulthood” (Côté, 2000, p. 1), which impede or generally keep young people away from key arenas of social integration, hence engagement in apprenticeship or training on the job, (further) education, paid work, family formation, civil movements or politics (Hurrelmann & Quenzel, 2013). Not only that, young people now have to face more complex, unclear and uncertain transition paths from youth to adulthood (Furlong et al. 2011: 361), but also they are facing high risks of intergenerational declines in job prospects and living standards (Roberts, 2012, p. 485-486).

These profound structural challenges do not remain without consequences for young people’s identities. As Bauman suggests “identities seem fixed and solid only when seen, in a flash, from outside. Whatever solidity they might have when contemplated from inside of one’s own biographical experience appears fragile, vulnerable, and constantly torn apart by shearing forces which lay bare its fluidity and by cross-currents which threaten to rend in pieces and carry away any form they might have acquired” (Bauman, 2000, p. 83).

Nevertheless, options to choose have never been so complex, multifaceted and open as they are today (Rasborg 2017; Hurrelmann & Quenzel, 2013). Youth today – especially in the industrialised countries of the Northern hemisphere – enjoy open and permeable national borders, can travel around the globe, have more educational and employment options as well as lifestyle and partner choice options than ever before. Freedom of travel, speech, political participation, and participating in a consumer society, with plenty of leisure activity options, are the hallmarks of our time. This has resulted in “greater degrees of freedom and choice in a rapidly changing world” (Miles, 2000, p. 18) and has empowered young people “in the sense that it gives them a semblance of control over their personal biographies” (Miles, 2000, p. 53). Correspondingly, youth today is capable of reinterpreting, bypassing or innovating life course specific patterns of transitions while breaking-up, transforming or circumventing traditional patterns of transitions of parent culture (Furlong et al. 2011: 361).

This tension between insecurity and unpredictability – hence risk – on the one hand[1] and growing opportunities and incentives on the other hand – hence choice – make the mixture of present-day practices of young people on their way from youth to adulthood. As Furlong and Cartmel (2007, p. 8-9) point out “Young people today are growing up in different circumstances to those experienced by previous generations; changes which are significant enough to merit a reconceptualization of youth transitions and processes of social reproduction. In other words, in the modern world young people face new risks and opportunities.” We will call this phenomenon risk-choice-freedom-paradox. Risks emerge from processes of de-standardization and ‘fyzzysation’ of the life course (Heinz 2009: 3), from the individualisation of decision costs, of behavioural uncertainties and practice responsibilities (Blossfeld et al., 2005, p. 16), and from the continuing power of structural position which shape the odds for successful coping with risks (Furlong et al. 2011: 363). Choice appears from an increasingly commodified, consumption focused material market environment promising opportunities for self-development, for freedom to choose, for self-responsibility (Miles 2000: 51; Heinz 2006: 3) while camouflaging the still existing forces of stratification patterns which pre-structure the chances for realising perceived opportunities (Rasborg 2017: 242). Freedom emerges from a consciousness that one can choose and perform modes of life, transitions and pathways according to his own preferences, aims and goals (Beck 1992: 130). The Paradox, however, emerges from a “double-edged message” (Heinz 2009: 3ff.) perform your choices, perform them “according to market opportunities and institutional rules” (ibid.) as well as feel and take responsibility although your choices are induced and framed by structural and institutional constraints (Woodman 2009: 251). Hence, decisions, responsibilities and outcomes of practices become ‘individualized’ and seen as product of ones ‘choice’ whereupon this ‘framing’ obstructs the limiting or enabling role of hidden structural and institutional forces (France and Haddon 2014).

It is exactly here where mobilities of young people take a key position in handling and practicing the forceful risk-choice-freedom-paradox (Beck, 1992, p. 94, 130). They provide, on one hand, options to choose between alternatives against the background of ones preferences, help to transform choices into mobility practices and thus foster social (networks, relations) and structural (educational and labour market) integration. Conversely, mobilities imply uncertainties and insecurities regarding the perception and choice of life-course related appropriate options, regarding the predictability of outcomes and life-course related unintended consequences of their individual mobility. Taking the risk-choice-freedom-paradox as theoretical starting point, this paper aims to highlight young people’s general international mobility experiences and, specifically, the interrelatedness of risks, choices and freedom under mobility. We will do this in an explorative manner combining quantitative and qualitative data from the international HORIZON 2020 research project on youth mobility – MOVE – which focuses on young people’s European mobility. Due to the complexity of possible mobilities we will only focus on employment mobility of the young to and from Norway.

2 Uncertainty and unpredictability

One of the key challenges of the risk-choice-freedom-paradox is uncertainty and unpredictability regarding the perception of life circumstances and the uncertainty and unpredictability of circumstances themselves. Therefore the framing processes of the situational complexities, and the outcomes of choices and decisions are all affected by the complex interrelatedness of processual structural, social and individual change (Abbott, 2016; Blossfeld et al., 2005; Furlong & Cartmel, 2007).

Particularly under the condition of globalisation, nationally or regionally organised employment, educational, welfare, social class and family systems have come under strain (Bauman, 2000, 2002; Blossfeld et al., 2005, p. 6; Grzymala-Kazlowska & Phillimore, 2018, p. 5). Bauman describes this as ‘liquidation’ of social and system integration “in which the conditions under which its members act change faster than it takes the ways of acting to consolidate into habits and routines. Liquidity of life and that of society feed and reinvigorate each other. Liquid life, just like liquid modern society, cannot keep its shape or stay on course for long” (Bauman, 2007, p. 1). Furthermore, as Giddens formulates it: “globalisation means that, in respect of the consequences of at least some disembedding mechanisms, no one can ‘opt out’ of the transformations brought about by modernity” (1991, p. 22).

Individuals are affected by these changes. Blossfeld et al. (2005) point to three central challenges, which the person has to deal with. The first challenge is the “rising uncertainty about behavioural alternatives” (Blossfeld et al., 2005, p. 16) not only when it comes to the kind of alternatives one has to choose between, but also with regard to its temporal contingence, hence, when to choose an alternative (Blossfeld et al., 2005, p. 17). To take international mobility as an example, young people are increasingly unsure if they should move abroad for some time or when they should move with regard to their educational, apprenticeship or employment track (Frändberg, 2014). The second challenge is that young movers can no longer be sure “about the probability of behavioural outcomes” (Blossfeld et al., 2005, p. 17). Presently, if a young person chooses to move abroad she cannot be sure about the outcome of her choice and the resulting practices. Certainly, public ideologies (Cresswell, 2006, p. 21) tell the young how important mobilities are regarding further educational, work and lifestyle prospects. They tell stories of lower risks of unemployment, lower job insecurities and lower risk of growing up and living in precarious life circumstances (Council of the European Union, 2004; Cresswell, 2006; Utenriksdepartementet, 2008). However, there are no guarantees that mobilities will have the anticipated positive outcomes during one’s life course (Urry, 2007, p. 271), perhaps in the short range but not concerning its long-term effects (Bauman, 2007, p. 27ff.; Graves, 1980; Urry, 2007, p. 271ff.). Finally, young people increasingly face “uncertainty about the amount of information to be collected for a particular decision” (Blossfeld et al., 2005, p. 17). Regarding the complexity of available information and the context specific variation of information conditions (selective, imperfect, informational overload) (Baláž, Williams, & Fifeková, 2016, p. 36) informational certainty with respect to mobility options, mobility conditions and mobility outcomes has become illusive (Baláž et al., 2016; Epstein, 2010; Herzog & Schlottmann, 1983; Maier, 1985). Individuals are called to take decisions that will be consequential for their future lives, so-called ‘fateful moments’ (Giddens, 1991, p. 112).

These challenges on the individual level are accompanied by institutional and structural insecurities and uncertainties. As already mentioned, the risk of economic uncertainty has risen over the last couple of decades (Furlong & Cartmel, 2007). Beck (1992, p. 140) describes this as a shift from a “system of standardized full employment to the system of flexible and pluralized underemployment”. However, not only has the risk risen for underemployment but also of overtime work which often is also underpaid, unstable and precarious (Furlong, 2014, p. 77; McDonald, Backstrom, & Allegretto, 2007; O’Reilly et al., 2015; White, 1997).

Accompanying the economic uncertainties and insecurities, social networks can come under strain when young people become internationally mobile (Ardic et al. 2018). Mobilities can potentially increase the risk of homesickness, feelings of alienation, cultural disturbances or psychological stress, since mobilities affects established social relation like the family, friends, peers or colleagues. This can lead to further social insecurities – like language and communication barriers, conflicts through network boundaries, double investment in compatriot and non-compatriot networks or the ‘slackening’ of family solidarity (Ardic et al. 2018, p. 221; King, 2018, p. 6). On the other hand, however, mobilities have the potential to bring about new relations, to foster intercultural learning and practice or open new network opportunities and network prospects (King, Lulle, Moroşanu, & Williams, 2016). This can lead to new ways of social-cultural and economic integration.

Cultural insecurity is an additional aspect in the context of mobility. Mobile youth face high odds that they meet different cultural norms and values, expectations regarding decision and daily life practices before, during or after their mobilities. Since culture “no longer sits in places, but is hybrid” (Cresswell, 2006, p. 1) young people have to cope with cultural ambiguities, differences and complexities.

The same applies to institutional challenges or insecurities. In the context of mobility, young people have to deal with different institutional routines, issues of the recognition of degrees, institutional codes and practices. Young people may ask themselves: “Do I get a work permission; do I have the right documents; are my former educational degrees accepted or is there a risk of devaluation and non-acceptance of former qualifications; where do I have to search or apply for a job”, etc.?

Of course, mobilities at the first instance are perceived as a way for increasing life prospects, chances and opportunities. Nevertheless, the intersection of the different uncertainties makes mobilities to a risk-choice-freedom challenge which increase and not reduces “intentional unpredictability” (King, 2018, p. 6) in the sense of “keeping options open” (King, 2018, p. 6).

3 Data and Methodology

The research discussed in this paper is part of a H2020 project MOVE: Mapping mobility - pathways, institutions and structural effects of youth mobility in Europe. In this particular study, we focus on experiences of uncertainty among young European workers ‘on the move’, through a combination of survey and semi-structured interviews.

In order to capture the risk-choice-freedom-paradox young people experience under mobility, quantitative analyses were performed using micro-data from a proportional online-survey that was based on population’s sex and age-group distribution (Navarrete et.al, 2017: 23), which was conducted in Germany, Hungary, Luxembourg, Norway, Romania, and Spain with mobile and non-mobile youth (N=5,499) aged 18-29 holding at least one of the consortium nationalities, or having obtained the secondary certificate/diploma in any of the six participating countries (Navarrete et.al, 201: 23).[2] The online panel survey was conducted between November 2016 to January 2017.

To explore the paradox quantitatively we focused on reasons – as proxies for choice – and perceived challenges – as proxies for perceived risks – in the context of young people’s mobility. In doing so, we used two sets of questions, which were applied to map reasons (as proxies for choice) to move and challenges the youth face under mobility.[3] In a first step, we select those young people from our sample, who have been internationally mobile in the context of employment mobility. In a second step, we merged all these mobile young – independently of the number of their mobilities – in one employment mobility group vs. a group ‘other mobilities’ for examining the risk-choice-freedom-paradox.

The quantitative data regarding mobile youth from six countries will be used to outline reasons and challenges – thus choices and perceived/experienced risk – of mobility in a general manner. The qualitative data[4], however, will be used to scrutinize the addressed paradox in depth. From our point of view combining both data sources and restricting our in depth qualitative analysis to only one case will provide new insight into the chances and challenges young people face in the context of their international mobility.

For measuring reasons for mobility the young were asked the following question “Generally speaking, what reasons do you consider most important to spend some time/move abroad?”. From 16 answer possibilities, the young should choose a maximum of three answers.

The mobility challenges are measured with the question “Generally speaking, which obstacles do you face/have you faced to spend some time/move abroad?”. The young could choose from 12 answer possibilities a maximum of 3 answers.[5]

In order to explore the paradox qualitatively in the context of mobility, explorative interviews with mobile youth were analysed. The qualitative case study of MOVE comprised different modes of mobility in the six above-mentioned countries. We use an empirically grounded, explorative perspective to address our research question. The target group of this paper consists of young people who became mobile within the context of employment mobility in Europe. Our sample group consists of 15 semi-structured interviews with young workers in the age group 18-29 years old. All interviews were conducted during their mobility experience and include both incoming European workers to Norway and outgoing workers from Norway to other European countries. The data collection took place between January and December 2016.

During the interviews, some of the topics we discussed were:

· Circumstances before mobility (e.g. living situation, finances, the idea to go abroad, organisation of mobility)

· Experiences being abroad

· Critical/challenging moments, obstacles before/during mobility

The interviewees were recruited via different sources, personal and professional networks, direct contact with companies/business and national institutions working with young employees. The interviewees represent both incoming and outgoing young employees. Our original intention was to create a sample group with an equal number for both genders. However, in the end the total sample consists of three males and 12 females. 12 out of 15 are incoming mobile from; Iceland, Germany, Estonia, Sweden, Spain, France, Poland and Austria. Three out of 15 young employees are Norwegians working in Belgium and England.

The qualitative data analysis was carried out by a computer-assisted open coding and ‘core theme identification’ and analyses (Bernard, Wutich & Ryan, 2017), where the specifics of the process towards employment mobility as well as reflections on experiences during cross-border mobility were taken into consideration. During this process, we further identified that all interviewees talked about how being mobile also include ‘living with uncertainties’, accepting them and coping with them.

3.1 Quantitative hints regarding the risk-choice-freedom-paradox

To cast light on the risk-choice-freedom paradox, particularly insecurities and uncertainties during employment mobility, we will first focus on reasons (Czeranowska, 2019) for youth mobility and followed on challenges the young perceive in the context of their mobility(ies). In a third step, we will further analyse if some of the young are more prone to risk and insecurity than other mobile young.

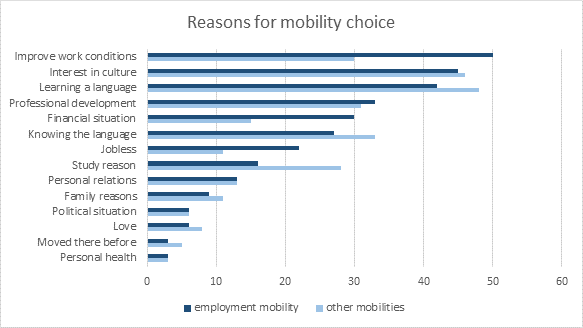

As one would expect young people have many different reasons for getting on the move. They range from individual development to more institutional or structural related reasons. However, as the graph 1 reveals some reasons are more important for the young than others in the context of their international mobilities. Especially reasons regarding the improvement of work conditions, interest in a different culture, and language learning are most central reasons for the mobile young. Between 40%-50% of the young agree on these aspects. This cluster of reasons is followed by a second one, which includes the reasons for professional development and a change of the personal and financial situation to the better. Knowing the language and joblessness are third important motivational aspects for getting on the move. Study issues, personal or family relations, the political situation, love, ‘moved there before’ and health issues are of comparatively lower importance for mobility. Less than 20% of the young name these reasons. However, concerning insecurities, uncertainty and unpredictability it is an important fact that only 3% of the young get on the move because they had been in the destination country before. Hence, almost all of the young decide to move to a place abroad without having experienced this place – its social, cultural and economic conditions – before. We will later discover in the qualitative part that this non-familiarity with the place of destination increases the risk of uncertainty for many young people and becomes therefore a central factor for understanding youth’s transition practices in the context of the risk-choice-freedom-paradox.

Graph 1 Reasons for mobility choice

Note: Category ‘other mobilities’ includes pupil exchange, mobilities in the context of apprenticeship, volunteering, entrepreneur and study mobility; employment mobility N=400, other mobilities N=5099

If one compares employment mobility with ‘other mobilities’ the graph clearly indicates (as one would expect) that improvement of work is the most frequently reported driving factor for young people’s employment mobility. However, the interest in a different culture, language learning and professional development are the drivers in all of the mobilities measured here.

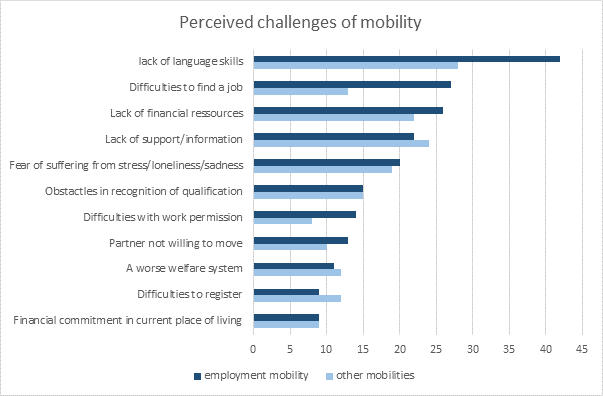

Since the majority of the mobile young moves to unknown ‘land’ they face different challenges regarding their mobility. To find out more about risk related subjective perceptions in the context of youth mobilities, we asked the young people about the challenges they have faced during their mobilities (graph 2).

Graph 2 Perceived challenges of mobility

Note: Category ‘other mobilities’ includes pupil exchange, mobilities in the context of apprenticeship, volunteering, entrepreneur and study mobility; employment mobility N=400, other mobilities N=5099

As the graph shows lack of language skills is perceived as the most important challenge in the context of mobility. More than 40% of the mobile young in the context of employment mobility agreed upon this. This is significant lower among the other mobilities. As one would expect, also difficulties to find a job are much more important in the context of employment mobility than in the context of other mobilities. Being on the move for employment reasons implies a high risk of not having the necessary language skills, of having difficulties to find a job, high risks of lack of financial resources (as we have seen quite often also a reason to move), support and information. It also implies fear of suffering or real suffering from stress, loneliness and sadness while moving. Other challenges, like qualification recognition, issues with work permissions, partner, welfare and register issues and outstanding former debts are named less often.

As we can see from these results, the social fact of international mobility combines at the same time both: perceived opportunities represented by the reasons of the young and perceived challenges or risks. Mobility implies the freedom to discover new places and contexts but at the same time, it brings about insecurity and unpredictability before, during and after. This dissonant social practice – having mobility choices, using this option for realising certain reasons but also taking risks and insecurities into account while moving – nowadays seems characteristic for young people’s mobility. This from our point of view underpins the risk-choice-freedom-paradox young people are forced into while being internationally mobile during their transition from youth to adulthood.

3.2 Findings from the qualitative material

As discussed in the quantitative findings above, ‘mobile being’ presents various degrees of uncertainty and difficulty for the youth, something also all of our interviewees expressed during the interviews. Whereas quantitative data reveal the reasons behind the mobility choices and perceived challenges during mobility, the qualitative data findings allow us to examine the level of individual experiences and reflections on uncertainty and unpredictability during young people’s employment mobility.

The young in our sample group describe mobility as a status transition, e.g. transition between unemployment to employment or from education to employment. In some of our cases, mobility decisions represent a way out – an escape from difficult conditions; in other cases it expresses a desire to take a chance and open up for new possibilities. However, regardless of the reason behind the mobility decision, young people are aware of and cope with various uncertainties that come along with their mobility experience.

The explorative analyses of the data material regarding uncertainties in mobility experience indicate the following three main aspects: 1) Personal and institutional uncertainties, 2) Economic uncertainties in the labour market, and 3) Social and cultural challenges in everyday life.

Personal and institutional (un)certainties

In the process towards mobility, young people go through a negotiation process with themselves. Moving abroad is often related to exploration of future social and professional opportunities. The freedom to choose between all of the alternatives can be overwhelming and challenging. Firstly, deciding on what is best for them (being mobile or not) and secondly, when it is the best time to move. Many of our interviewees highlighted the amount of time they have spent deciding on where to go and what kind of job they could secure. The decision-making process towards actually taking a step out and becoming mobile carries many uncertainties. Young people are concerned about making the right choice in their current situation, but also thinking more rationally about what choices today will give them the best outcomes for the future.

It was kind of - okay, choosing what kind of path you want to go. If you want to stay in (city in Norway) with your close friends, and what you know, or if you want to go abroad and then live a little extra kind of. (Vera[6], Norwegian, 26 years old)

I think it (moving to Norway) will help us to get to places we want to be a bit faster because we can save money here and maybe build a house, which is his dream, and I don’t want to be the reason why he can’t do things. That’s maybe why I wanted to try to move because I wanted to try to do a little better. (Hilda, Icelandic, 27 years old)

Weighing advantages and disadvantages before making a final decision of going abroad is an important part of the process towards mobility. Reflections about taking a chance / risk, but also the dilemma of leaving behind your duties at home vs. freedom and openness to go abroad were present in several interviews. Magda and Maria, in the examples below, see their mobility decisions as ‘fateful moments’ that will be particularly consequential for their ambitions and their future lives (Giddens, 1991, p. 112).

I was asking myself several times if that was the right decision for me. At one point, I was just not sure that going to a new country and learning something entirely new was what a responsible person should do. I had the sense of responsibility deep into me because of my parents’ way of raising me. I was always taught to be responsible, thinking about the future and my duties. (Magda, Polish, 28 years old)

It is a proper time to go abroad when you are young. Think that you do not have family responsibilities or you do not have a full time job, you are still wondering who you are, you are trying to take your position in the society, and you are also young, like biologically young. You are free to explore and experience. (Maria, Spanish, 28 years old)

Being young and having less obligations to, for example, a partner, child, finances etc. gives young people more freedom to take the chance of going abroad. Conversely, despite not having those “grown-up” obligations, some young people express being caught in the dilemma (like in the case of Magda) between the family expectations and their own aspirations. This risk-choice-freedom paradox shows to be very complex and the young have to consider a variety of factors before taking the decision to move. This freedom of choice, also includes a coercive element, where compulsion to make this particular choice can be considered as a characteristic feature of our current society. The increasing opportunities and challenges around young people push them to consider what they really want and need, and eventually give them a sense of control over their personal biographies.

As described in the theoretical part of this paper, the uncertainties on the individual level are linked to institutional and structural insecurity. Lack of support and information was highlighted in the quantitative data, and was mentioned by some of the young people in our qualitative sample group. As expected, all mobile youth went through various bureaucratic processes, for example registration at the tax office, police station, health system and other offices. The narrations from Gina and Lucas below demonstrate their struggle with the bureaucratic system in the destination country.

I was told there is some uncertainty as to what rules apply when you’re on a one-year contract in an EU country. So, anyone I was talking to was basically giving me a different answer as to “do I have to apply to stay insured in Norway?” (…) Yeah, it took a lot of time (…) it seemed like generally there was a lack of knowledge as to what rules apply, if you’re in an EU country versus being in America or something like that. At least with the people I spoke to, it was never really clear. Everyone was kind of sending me around. (Gina, Norwegian, 24 years old)

It went actually quite smoothly but I had a problem at the police office. (…) The people in the office were quite helpful, but the information on their webpage does not match what they require from the person. At some point, they ask me where your rent contract is, and I said “do I need that?”. Yes. “Ok then I will bring it.” In addition, I had to go back there many times (…) It is like error all the time. They say: Bring that - now you need that - oh not that one - come now, no come later - it is too soon, come later. I just think: “what the f***, can you tell me please everything at once. It is tiring.” (Lucas, Spanish, 26 years old)

Absence of organisational support is clearly illustrated in the examples above, this is often due to the fact that young people go abroad to find a job on an individual basis and without support from other organisations or institutions. The issue of paperwork and bureaucracy came up frequently in the interviews with young people and was often considered as a tiring and, at times, confusing process. Interestingly, these processes were not mentioned wholly negative or impossible. At the time of the interviews, all of the young people in our sample group were employed and mobile, as they had already overcome their bureaucratic hindrances.

Economic (un)certainties in the labour market

Research shows that young people entering the labour market experienced more directly the global increase of insecurity. They are unprotected by seniority and have no strong ties to work organisations or work environment (Mills and Blossfeld, 2005, p. 6). The narratives below from Hilda and Maria, show us examples from young employees in Norway, who point to unsatisfying economic situations in their home countries as a push to becoming mobile. Even though, there is no guarantee that their decision to move will bring positive change to their everyday life, they took the risk to try this new opportunity to make changes in their life.

One day when I was going home from work after I got paid, I called my boyfriend and say “we have to go”. It’s not easy in my country, you can’t do anything, it’s so expensive and you can’t save up money to buy a house or apartment. The salaries are not good. (…) I think moving here will help us to get to places we want to be a bit faster because we can save money here and maybe build a house (…) because in my country we always think about the future and there is an uncertainty about everything. We always wonder what will happen? Is this going to be fine? (Hilda, Icelandic, 27 years old)

In my country, our situation was very bad. We had quite hard crises, as many countries in Europe and for two years I was already unemployed. I am a social educator and the social services were the first things they were out cutting the money. In addition, after so many years being unemployed, it was the time for me to do something. (Maria, Spanish, 28 years old)

The narratives above clearly demonstrate that economic uncertainty has a big effect on the decision to move abroad, regardless of being employed or unemployed before mobility. However, our data reveals that entering the labour market in a new country is not easy for the mobile we have interviewed. For some, despite having a higher education diploma they still struggle to find a relevant job according to their educational background. The statement of Lucas, below, is a good example that illustrates a process many young people have to go through before finding a satisfactory position in the labour market:

In the beginning I worked at a Travel Agency, I worked a little bit in a restaurant also, then a hotel, then I was three weeks as a tiler, the one that puts the tiles on the roof of houses. Haha, in Norway I have worked with almost everything I could. It´s not cheap to live here, I need the money. So it is like, traveling around building stuff, hotel, tour guide, and now the new job I will start in February, so 6 jobs so far. (…) I actually didn´t expect to survive that long, but so far I am doing good, I´m still alive. (Lucas, Spanish, 26 years old)

Lucas’s experience is a good example of what some young employees have to deal with when moving to a new country in order to improve their economic position. Lucas had to start from the bottom, in informal and low-skill sectors with irregular employment. This is the case for many mobile young, where the lack of labour market connections likely increases the chances of informal or irregular employment. Interestingly, they take on risk of precariousness hoping and believing to reach a more stable position in the future. This motivates them to cope with economic uncertainties by moving to another country for purpose. Hence, they perform mobility practice based on strategies, ideas, beliefs, dreams or hopes expecting an improvement of their life circumstances.

Similarly to Lucas, Magda told us about her low expectations of finding a relevant job but also the acceptance of it as a part of the mobility process:

In my home country I was a translator, so it’s a relatively ambitious job and it’s connected with my education. It’s something that I have studied. By going to Norway I knew that I would probably agree with doing some small jobs that have nothing to do with my education. (Magda, Polish, 28 years old)

Social and cultural challenges in the everyday life

A young adult recently employed in a foreign country may experience this as having reached his/her ‘mobility dream’. Despite the difficulties in the labour market, this person has achieved some economic security. However, mobility experience has a broader effect on their life. In addition to adapting to a new working environment, they discover cultural differences, being challenged by the use of a new language and trying to build social relations in the unknown ‘land’.

Similarly, to the results in the quantitative section, our qualitative results show that the lack of language skills creates many uncertainties in the social life. For example, interaction with locals, understanding the regulations and making meaningful relationships.

I find it very hard getting good contact with the Norwegian people. It is as if they already have a good group of friends and things like that, they don’t need an immigrant. I don’t know if I could get many Norwegian friends. So, my best friends here in Norway are Germans. (Ine, German, 29 years old)

Social relationships and friendships are important for young people. As illustrated above, Ine found it hard making friends with the natives and had the closest relationships with her compatriot peers (Ardic et al. 2018: 209). Despite some critical aspects related to compatriot peer relations (e.g. preventing mobile young fully embracing a new culture), our sample group clearly demonstrates the importance of compatriot peers in the destination country to help them tackle the challenges of living abroad and reducing insecurity and the risk of becoming socially and culturally marginalised by mobility.

Making meaningful relationships with locals in the destination country is not easy. Particularly the language barriers and lack of cultural competence in the unknown society made it hard for mobile people in our sample group to feel fully included and accepted in their workplace or to bond with locals.

Every time when I say that I prefer English, they look at me like “Really?” ... and some, they don’t even want to speak with you when they find out that you don’t speak their language. (Anna, Estonian, 21 years old)

When I arrived to Norway, I was very cheerful, touchy and very Spanish. After two days, they sent me to the mountain trip with my pupils (add. remark: Maria worked as a teacher), 48 hours trip in the nature with Norwegian youth. At first, I was very cheerful and tried to talk to them. I was very surprised because no one answered to that in the group. When I was talking to them, they did not look at my eyes; they refused to speak in English. I had to spend 48 hours with Norwegian teenagers while not being able to speak any Norwegian myself. I was alone in the amazing Norwegian nature and that was it. I thought this is going to be my year, amazing mountains, but how do I ‘climb’ to these people? (Maria, Spanish, 28 years old)

Mobility researchers, for example Cairns et al. (2017) point out that while there are some genuine success stories, attempts to live the mobility dream also involve disappointments in becoming and staying mobile (2017, p. 3-4). Despite being employed, Anna and Maria tell about the social and cultural difficulties they face as foreign workers in Norway. Different cultural codes bring insecurity on how to behave and communicate in various social settings. Symbolic boundaries, here between the locals and the ‘newcomers’, become more obvious under mobility and even seen as a hindrance that need to be ‘climbed’ over.

In this qualitative part, we have explored some of the effects of youth mobility in the context of employment. Beginning with personal and institutional challenges facing the youth themselves, and then considering the effects of the economic uncertainties in the labour market as well as the significance of socio-cultural challenges in their everyday life. As one might expect, these uncertainties are not uniform and young people cope with them in various ways. In light of the risk-choice-freedom-paradox, we can conclude that young people on one hand express their awareness of economic, social, cultural, institutional and personal risks they may face in the destination country, but on the other hand, because of perceived challenges at home, they see mobility as freedom to explore what is ‘out there’. For many of the young people, then, the issue of risk-choice-freedom seems to be unavoidable.

4 Concluding remarks

This paper demonstrates that ‘mobile being’ introduces young people to new everyday practices, new social and cultural norms, and new labour market opportunities and challenges and emphasises mobility dynamics in the context of insecurity and unpredictability. Our contribution reveals various nuances about individual concerns, hopes and choices made by young people in the context of international mobility. It also fosters our understanding of the risks met by young employees in Europe, for instance linguistic difficulties, the struggle of understanding the social codes and creating meaningful relationships. In addition, entering an unknown labour market brings about bureaucratic processes young people need to cope with.

Hence, chances, choices and challenges on the individual level are accompanied by institutional and structural insecurities and uncertainties. In the context of mobility, young people have to deal with different institutional routines, issues of the recognition of degrees, institutional codes and practices. Cultural challenges – here especially language issues – are a further aspect in the context of mobilities. Hence, mobility does not only bear positive outcomes and is not always straightforward regarding individual transitions and pathway choices. Rather, it includes risks, obstacles and pitfalls that the young face before, during or after their mobility and calls for individual strategies to cope with. Young people feel free to choose mobility options which are provided by market opportunities and framed by institutional expectations, face anticipated but also not anticipated risks and have to bear the individualised consequences of their practice. Hence, the young are aware that their mobilities are not just self-directed but framed by institutional structures and structure based inequalities. This indeed marks the forceful risk-choice-freedom-paradox young people are engaged with in the contexts of international mobility in particular and their transition from youth to adulthood in general.

Our findings demonstrated how individuals learn to live with uncertainty and unpredictability during their employment mobility. Even though, there is no guarantee that their decision to move will bring positive change to their everyday life, they take the risk to try this new path to bring changes to their life. The risk-choice-freedom paradox is a complex one and young people have to consider many different things before taking the decision to move. Reflections on risk, responsibility and identity always accompany mobility when seen as a path to possibility and freedom.

Comparing individual mobility experiences is due to its macro, meso and micro level related complexities not easy to obtain. One of the major strength of our study is that it combines quantitative and case specific qualitative data to explore the risk-choice-freedom-paradox in an innovative manner. However, one central weakness is that the chosen approach does not allow for generalisations regarding national mobility contexts, their specific characteristics and contextual variations of individual perceptions and strategies in dealing with the risk-choice-freedom-paradox.

References:

Abbott, A. (2016). Processual Sociology. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press.

Ardic, T., Pavlova, I., & Skrobanek, J. (2018). Being international and not being international at the same time. The challenges of peer relations under mobility. In Det regionale i det internasjonale: Fjordantologien 2018 (pp. 206-222). Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

Baláž, V., Williams, A. M., & Fifeková, E. (2016). Migration Decision Making as Complex Choice: Eliciting Decision Weights Under Conditions of Imperfect and Complex Information Through Experimental Methods. Population, Space and Place, 22(1), 36-53. doi:doi:10.1002/psp.1858

Bauman, Z. (2000). Liquid Modernity. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Bauman, Z. (2002). Society Under Siege. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Bauman, Z. (2007). Liquid Times (Vol. 2). Cambridge: Polity Press.

Beck, U. (1992). Risk Society: Towards a New Modernity. New Delhi: Sage.

Bendit, R., & Miranda, A. (2015). Transitions to Adulthood in Contexts of Economic Crisis and Post-Recession. The Case of Argentina. Journal of Youth Studies, 18(2), 183-196. doi:10.1080/13676261.2014.944117

Blossfeld, H.-P., Klijzing, E., Mills, M., & Kurz, K. (2005). Globalization, Uncertainty and Youth In Society. London: Routledge.

Cairns, D., Cuzzocrea, V., Briggs, D., & Veloso, L. (2017). The Consequences of Mobility: Reflexivity, Social Inequality and the Reproduction of Precariousness in Highly Qualified Migration. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

Côté, J. E. (2000). Arrested Adulthood. The Changing Nature of Maturity and Identity. New York: New York University Press.

Council of the European Union. (2004). Immigrant Integration Policy in The European Union. Brussels: European Union Retrieved from http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_PRES-04-321_en.htm?locale=en

Cresswell, T. (2006). On the Move. Mobility in the Modern Western World. New York London: Routledge.

Czeranowska, O. (2019). Janus-Faced Mobilities: Motivations for Migration among European Youth in Times of Crisis AU - Salamońska, Justyna. Journal of Youth Studies, 1-17. doi:10.1080/13676261.2019.1569215

Epstein, G. S. (2010). Chapter 2 Informational Cascades and the Decision to Migrate. In G. S. Epstein & I. N. Gang (Eds.), Migration and Culture (Vol. 8, pp. 25-44): Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

European Union. (2010). Youth on the Move, A Europe 2020 Initiative. Retrieved from http://ec.europa.eu/youthonthemove/

France, A., & Haddon, E. (2014). Exploring the Epistemological Fallacy:Subjectivity and Class in the Lives of Young People. YOUNG, 22(4), 305-321. doi:10.1177/1103308814548108

Frändberg, L. (2014). Temporary Transnational Youth Migration and its Mobility Links. Mobilities, 9(1), 146-164. doi:10.1080/17450101.2013.769719

Furlong, A. (2014). Youth Studies. An Introduction. New York: Routledge.

Furlong, A., & Cartmel, F. (1997). Risk and Uncertainty in the Youth Transition. Young, 5(1), 3-20. doi:10.1177/110330889700500102

Furlong, A., & Cartmel, F. (2007). Young People and Social Change. New Perspectives (Second edition ed.). New York: Open University Press.

Furlong, A., Woodman, D., & Wyn, J. (2011). Changing times, changing perspectives: Reconciling ‘transition’ and ‘cultural’ perspectives on youth and young adulthood. Journal of Sociology, 47(4), 355-370. doi:10.1177/1440783311420787

Giddens, A. (1991). Modernity and Self-Identity. Self and Society in the Late Modern Age. Cambridge: Policy press.

Graves, P. E. (1980). Migration and Climate. Journal of Regional Science, 20(2), 227-237. doi:doi:10.1111/j.1467-9787.1980.tb00641.x

Grzymala-Kazlowska, A., & Phillimore, J. (2018). Introduction: Rethinking Integration. New Perspectives on Adaptation and Settlement in the Era of Super-Diversity. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 44(2), 179-196. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2017.1341706

Heinz, W. R. (2009). Youth Transitions in an Age of Uncertainty. In A. Furlong (Ed.), Handbook of Youth and Young Adulthood (pp. 3-13). London: Routledge.

Herzog, H. W., & Schlottmann, A. M. (1983). Migrant Information, Job Search and the Remigration Decision. Southern Economic Journal, 50(1), 43-56. doi:10.2307/1058039

Human Development Report Office. (2010). Mobility and Migration. Retrieved from http://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/nhdr_migration_gn.pdf

Hurrelmann, K., & Quenzel, G. (2013). Lost in Transition: Status Insecurity and Inconsistency as Hallmarks of Modern Adolescence. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 2013(5), 1-10.

King, R. (2018). Theorising New European Youth Mobilities. Population, Space and Place, 24(1), e2117. doi:doi:10.1002/psp.2117

King, R., Lulle, A., Moroşanu, L., & Williams, A. (2016). International Youth Mobility and Life Transitions in Europe: Questions, Definitions, Typologies and Theoretical Approaches. Retrieved from Sussex: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/61441/1/mwp86.pdf

Lockwood, D. (1964). Social Integration and System Integration. In G. K. Zollschan & W. Hirsch (Eds.), Explorations in Social Change (pp. 244-257). London: Houghton Mifflin.

Lorentzen, T., Bäckman, O., Ilmakunnas, I., & Kauppinen, T. (2018). Pathways to Adulthood: Sequences in the School-to-Work Transition in Finland, Norway and Sweden. Social Indicators Research. doi:10.1007/s11205-018-1877-4

Maier, G. (1985). Cumulative Causation and Selectivity in Labour Market Oriented Migration Caused by Imperfect Information AU - Maier, Gunther. Regional Studies, 19(3), 231-241. doi:10.1080/09595238500185251

McDonald, P., Backstrom, S., & Allegretto, A. (2007). Underpaid and Exploited: Pay-Related Employment Concerns Experienced by Young Workers Youth Studies Australia, 26(3), 10-18.

Miles, S. (2000). Youth Lifestyles in a Changing World. Philadelphia: Open University Press.

NOU 2012:2. (2012). Utenfor og Innenfor- Norges Avtaler med EU. Retrieved from https://www.regjeringen.no/no/dokumenter/nou-2012-2/id669368/: Utenriksdepartementet

O’Reilly, J., Eichhorst, W., Gábos, A., Hadjivassiliou, K., Lain, D., Leschke, J., . . . Villa, P. (2015). Five Characteristics of Youth Unemployment in Europe: Flexibility, Education, Migration, Family Legacies, and EU Policy. SAGE Open, 5(1), 2158244015574962. doi:10.1177/2158244015574962

Rasborg, K. (2017). From Class Society to the Individualized Society? A Critical Reassessment of Individualization and Class. Irish Journal of Sociology, 25(3), 229-249. doi:10.1177/0791603517706668

Roberts, K. (2012). The End of the Long Baby-Boomer Generation. Journal of Youth Studies, 15(4), 479-497. doi:10.1080/13676261.2012.663900

Sironi, M. (2018). Economic Conditions of Young Adults Before and After the Great Recession. Journal of family and economic issues, 39(1), 103-116. doi:10.1007/s10834-017-9554-3W

UNDP. (2015). Human Development Report 2009. Overcoming Barriers: Human Mobility and Development. Retrieved from New York: http://hdr.undp.org/en/content/human-development-report-2009

Urry, J. (2007). Mobilities. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Utenriksdepartementet. (2008). Internasjonalisering av utdanning (Meld St. 14 (2008– 2009)). Oslo: Norwegian Ministry of Education and Research Retrieved from https://www.regjeringen.no/globalassets/upload/kd/vedlegg/internasjonalt/internationalisation_14_2008_2009.pdf

Utenriksdepartementet. (2018). Norway in Europe. The Norwegian Government’s Strategy for Cooperation with The EU 2018–2021. Retrieved from https://www.regjeringen.no/en/dokumenter/eu_strategy/id2600561/

Walther, A. (2006). Regimes of Youth transitions: Choice, Flexibility and Security in Young People’s Experiences Across Different European Contexts. YOUNG, 14(2), 119-139. doi:doi:10.1177/1103308806062737

White, R. (1997). Young People, Waged Work and Exploitation. Journal of Australian Political Economy, 40, 61-79.

Author´s Address:

Prof. Jan Skrobanek

Department of Sociology

University of Bergen

Rosenbergsgaten 39/room 302

Postboks 7802, 5020 Bergen,

Norway

http://www.uib.no/personer/Jan.Skrobanek

Tlf: +47 55 58 9180

Author´s Address:

Tuba Ardic

Department of Social Sciences

Western Norway University of

Applied Sciences

Røyrgata 6, 6856 Sogndal,

Norway

https://www.hvl.no/person/?user=2404864

Tlf: +47 57 67 62 35

Author´s Address:

Irina Pavlova

Department of Social Sciences

Western Norway University of

Applied Sciences

Røyrgata 6, 6856 Sogndal,

Norway

Tlf: +47 57 67 6364