Punitiveness

and Devaluation among Social Work Gatekeepers

Johanna Pangritz, Bielefeld University

Wilhelm Berghan, Bielefeld University

1

Introduction

Over recent years, social work research

has increasingly focused on the topic of punitiveness. The empirical and

theoretical debate associates punitivity with a shift or change in the ideal of

resocialization. In this context, punitiveness stands as an expression or

symptom of the erosion of welfare state structures and attitudes at a time when

social work is moving away from a welfare state ideal of social rehabilitation

towards a “post-welfare state” with selective risk management and associated

coercive and control measures (Wacquant 2009; Dollinger 2017; Lutz 2017; Lutz

& Ziegler 2005). Here the question arises: to what extent does this

transformation coincide with a shift in the attitudes and mentality of agents

of the welfare state? In particular, the question asks how the shift is

specifically related to antidemocratic attitudes and intergroup conflict. Here,

the devaluation of minorities in the form of prejudices should be considered,

since they are the primary addressees of social work. In this context, social

work acts as a so-called “gatekeeper” of the welfare state, as it actively

shapes the welfare state through its professional actions. This also includes

assumptions about citizenship, as this involves assertions about who belongs to

society and who does not.

2

An Attempt to define punitiveness

The term punitiveness is widely used in

social work literature, even though there is no agreement on its definition.

It is therefore also viewed as a “blurry” (Kury, Brandenstein &

Obergfell-Fuch 2009: 63), “fuzzy” (Markusen 2003) or “largely undefined”

(Mathew 2005: 175) concept. However, it is probably this indistinctness that

makes the concept so successful. Punitivity proves a difficult construct to

determine for three principal reasons which are associated with Punitivity’s:

1.

Dimensions,

2.

Relationality, and

3.

Traits

Dimensions:

Punitiveness is not only a useful concept for characterizing attitudes, but it

can also be used to analyse and examine forms of practice, social structures,

and discourses. Kury, Brandenstein, and Obergfell-Fuchs (2009), for example,

differentiate three dimensions of punitivity at the micro-, meso- and

macro-level.

“On the micro perspective punitiveness

can be seen as a penal mentality or need for punishment of singular persons. On

this individual level, especially personal assumptions, attitudes, values,

concept and emotions, about which persons report are of interest,” (Kury,

Brandenstein & Obergfell-Fuchs 2009: 65).

On the meso-level the authors

differentiate between political and judicial punitiveness. While political

punitiveness focuses on the effects of policy and political practice, judicial

punitiveness concentrates on legality and decisions of the courts. The macro

level also includes social values that are important for the entire population

such as media discourses (Kury, Brandenstein & Obergfell-Fuchs 2009). This

makes punitivity difficult to pin down, since different developments are

possible at each level.

Relationality: The relationality of the term makes it difficult to grasp.

Dollinger (2011a: 32) argues that punitiveness cannot be specified in itself,

but rather describes a complex network of relationships. Lautmann and Klimke

(2004) make it clear that punitiveness can be understood as an excessively

punitive reaction to perceived norm deviations:

“A person or institution that

describes the actions of another person or institution as deviant from

normative point of view and supports negative sanctions is punitive in the

literal sense. Punitiveness is the generalized attitude or tendency to react

with negative sanctions to perceived norm deviations. [...] It refers to the

tendency to prefer retaliatory sanctions and neglect forgiving ones. [...]

Punitive is a certain way of using punitive sanctions, namely with harshness

and strictness,” (translated from Lautmann & Klimke 2004: 10).

The relationality of punitivity under this

definition is especially pertinent in two respects: on the one hand, the norm

deviation to which it refers serves as a starting point for punitivity. The

category of deviance is never neutral or descriptive, but always pervaded by

ideas about socially recognized and acceptable concepts of social order and

human nature. It also determines the point of intervention and subsequent

action (Dollinger 2008). This starting point is historically negotiable and

contingent and can therefore be described as relational. On the other hand,

categorization as “excessive” or “harsh” punishment must be described as

relational. What is understood as such in each case depends on different

institutional, cultural, or historical contexts and, therefore, on norms. It is

also assumed that there is an alternative possibility of action that can be

described as less or not punitive (Scheer & Ziegler 2013). Punitivity can

therefore only serve as a “relational variable” (Dollinger 2011a: 33) that

depends on specific reference points. One example is the term “punitive turn,”

which has emerged in social work discourses in recent years. This can only

happen with reference to a previous status, which is “not” or “less” punitive,

and is dependent on a normative reference point. These relational variables are

essential to identifying what constitutes a punitive turn and what it actually

represents.

Traits of punitivity: Finally, we have to consider which characteristics punitivity

includes. Some authors equate punitivity with authoritarianism or draw strong

parallels to it (Lautmann & Klimke 2004). The dimension of authoritarian

aggression in particular is described as an expression of punitivity (Mühler

& Schmidtke 2012; Mansel 2004). In this argumentation, punitiveness is part

of the syndrome of authoritarianism and not understood as an independent

concept. This characterization of punitivity is challenged by newer theoretical

perspectives on authoritarianism that argue that authoritarian individuals do

not necessarily tend to be aggressive.

“In a complex society full of

ambiguous situations, the individual must surely face many attacks. Even a

strong tie to leading authorities and rigid orientation towards their values

and norms cannot completely protect one against insecurity and anxiety. Because

authoritarian personalities have to develop mechanisms for dealing

independently with crisis situations, they feel themselves attacked very

easily. In combination with this lack of independence, the authoritarian

personalities’ poorly developed conflict-solving strategies place them in a

state of emotional and cognitive overload that in turn causes hostile

tendencies. […] From the point of view of the new theory described here

authoritarian individuals are usually not aggressive. The authoritarian

reaction as a flight into security excludes overt aggression. Aggressive

behavior always includes personal risks. Such risks are precisely what the authoritarian

reaction is designed to avoid. Yet although the authoritarian personality is

not aggressive in general, it could be considered hostile,” (Oesterreich 2005:

284).

In this understanding, authoritarianism

can be considered as almost contrary to punitivity. As long as punitivity is

conceptualized as both hostile and aggressive, the punitive actor is placed in

the forefront of conflict and therefore at risk. In the form of harsh

punishment, punitivity has a clear aggressive orientation, aimed at rigid

adherence to normative values. Punitivity can be characterized by an aggressive

component such as punishment which is based on and oriented towards

norm-conforming behavior. Punitivity therefore also includes conventionalism.

The authoritarian submissiveness conceptualized by Oesterreich (2005) and the

associated flight into security and stability do not focus on this element of

punitivity. Consequently, punitivity can be regarded as an orientation that is

related to authoritarianism but can also be quite distinct from the

authoritarian personality. Punitivity attempts to hierarchically subordinate

normatively deviant individuals, positions, and institutions (Stehr 2014). In

addition, punitivity suggests how to deal with deviation. This aspect is

still rather neglected in the conceptualization of authoritarianism. In this

context, punitiveness has a much more practical relevance.

The research presented here is based on

the definition of punitivity as an attitude on the micro-level. The normative

point of reference is the educational ideal, which is oriented towards

democratic and humanistic goals such as maturity, autonomy, and participation.

The importance of this educational ideal is particularly emphasized against the

background of current and historical dehumanization (Adorno 1982; Benner &

Brügge 2004). Punitiveness is therefore understood as a strong move away from

this normative ideal. In particular, the punitive shift is characterized by

aggressive procedures (harsh punishments), and pressure towards normative

conventions whereby penalties are applied to deviations from the social norm.

3

State of research: Punitive attitudes of social

work professionals and the link to devaluations of minorities

Previous theoretical and empirical studies

have drawn attention to the punitive shift away from the humanistic oriented

ideal of resocialization, often taking the attitudes of future professionals

into consideration (Oelkers 2013; Scheer & Ziegler 2013; Dollinger 2011b;

Dollinger & Raithel 2005). The attitudes of students tend to show a hard

line against deviant behavior, but also deviancy in the broadest sense. These

are indications that social work is in danger of moving away from its ideals.

Oelkers (2013) showed that more than half of students consider punishment to be

the best response to criminal behavior: social work professionals should

communicate clear limits (79 % agreement) and educate young people to behave

decently (66 %). This support is often coupled with skepticism about welfare

state structures. Scheer and Ziegler (2013) show that around 40 % of students

taking the introductory course in social work believe that the welfare state

leads people to take less and less responsibility.

Even if there is no direct link between

the attitudes of students and their later actions as professionals in the

field, research on professions shows that professional attitudes have a

biographical component (cf. Dollinger 2011b); as such, attitudes of students

can be regarded as indicative of later action. It is therefore not surprising

that similar trends can also be found among professionals in the field, (Mohr

2017; Clark & Schwerthelm 2017; Mohr & Ziegler 2012). Mohr and Ziegler

(2012), for example, found that around 40 % of professionals agreed with the

idea that the problems of social work clients are attributable to their

unwillingness to assume any responsibility. Furthermore, two fifths of

respondents wanted more possibilities for sanctions in the event there is a

lack of cooperation. Mohr (2017) found similar results. In his survey, around

40 % agreed with the idea that social work must reconsider values like

“discipline” and “order.” According to Mohr (2017), this mindset, which he

calls „respondilizing-disciplinizing” problem interpretation, is related to the structures

of the organization. Social workers in organizations that show professional

characteristics (i.e. autonomy, collegial decision-making, and orientation

toward the client’s needs) tend to show less of this mindset.

Lastly, it is worth highlighting findings

that suggest that punitiveness can be understood as a form or mechanism of

devaluation that solidifies current power relations (Dollinger 2017; Häßler

& Werner 2012; Klein & Groß 2011). These studies show that the punitive

tendency is intensified in relation to minorities (e.g. migrants or homeless

people). The findings of an experimental study by Häßler and Werner (2012) are

particularly noteworthy for the context of social work and citizenship. Using a

student sample of (mainly German) future social workers, they were able to show

that longer and harsher sentences were advocated for juvenile offenders who had

a first name that sounded “foreign”. However, the authors add that these

findings do not automatically suggest devaluing attitudes towards other ethnic

groups, but instead, they argue that this must be examined separately.

4

Punitiveness and devaluation: Interim conclusion

and hypotheses

Previous research on punitivity provides

some evidence that punitivity is a mechanism that contributes to the

maintenance of social hierarchies. It also shows that a punitive educational

orientation in social work weakens or strongly limits the democratic or

humanistic ideal. A punitive orientation on the part of the educators is

difficult to reconcile with democratic and humanistic educational ideals and

furthermore it is connected with an education aimed at adaptation and

conformity. It is also clearly related to antidemocratic attitudes of social

workers themselves, who in this context act as gatekeepers of the welfare

state. Those who demand tougher punishments and discipline and unquestioned

adherence to a given framework of norms are more likely to devalue groups that

are seen as foreign (e.g. “the Muslims”) or deviant (e.g. due to homosexuality)

under socially established norms that are subjectively considered important.

Punitivity is therefore related to the denial of the democratic ideals of

equality and belonging by devaluing certain social groups through negative

prejudices. Following these considerations, it will be demonstrated empirically

that punitivity is not only detrimental to democratic ideals, but fundamentally

contrary to them by devaluing vulnerable groups through punitivity. From this,

the following hypotheses can be derived:

- H1: Respondents who agree with a punitive

educational orientation are more likely to show negative prejudices toward certain social groups.

- H2: There is a relationship between a punitive

educational orientation and the devaluation of differing groups.

5

Method

5.1 Execution and Sample

The results are based on data from an

online survey conducted in January and February of 2018. With the help of a

so-called snowball sampling procedure, the request for participation was sent

to colleagues of the two authors, who then forwarded it via their respective

networks – mainly in educational, academic, and social work institutions. The

survey was thus aimed at a group who can be categorized as “street-level

bureaucrats.” Out of a total of 266 respondents in this convenience sample, 161

(60.5 %) completed the questionnaire completely. As far as possible, the

analyses also include those respondents who completed a large part of the

questionnaire; as a result, the sample on which the main analysis is based

contains 178 respondents. The majority of the sample consists of students

(n=130). The students varied in their studies: social work (44.3 %),

educational science (39.4 %) sociology (9.0 %), psychology (3.3 %), and other

subjects (4.0 %). The sample also included other social or nursing occupations

(10.0 %), and other professions (8.7 %). All occupational groups are included

in the calculations.

5.2 Operationalization

Prejudices were operationalized using

instruments for measuring group-focused enmity that have been in use for many

years and published in numerous studies (Zick, Küpper & Berghan 2019; Zick,

Küpper & Krause 2016; Zick & Klein 2014; Zick et al. 2008). The items

were answered on a five-point Likert response scale with the following (ad hoc

translated) characteristics: 1 = completely disagree, 2 = partly disagree, 3 =

partly agree/partly disagree, 4 = partly agree, 5 = completely agree. The

following elements of group-focused enmity were captured with two items each:

racism, hostility towards foreigners, hostility towards Muslims, devaluation of

Sinti and Roma, devaluation of asylum seekers, privileges of the established

(or hostility towards newcomers/outsiders), antisemitism, devaluation of the

long-term unemployed, devaluation of the homeless, classical sexism,

devaluation of trans people, and devaluation of people with disabilities.[1]

Two additional items to classical sexism were included to operationalize modern

sexism to complement the coverage of classical sexism.

Table 1: Original German wording of

the Group Focused-Enmity items and ad-hoc translation in English (means,

standard deviations, and Cronbach's alpha values)

|

Racism (V = RA;

M = 1.25; SD = .55; n = 174; α = .61)

|

|

Aussiedler sollten besser

gestellt sein als Ausländer, da sie deutscher Abstammung sind.

[Resettlers

should be treated better than foreigners, because they are of German

descent.]

|

|

Die Weisen sind zu Recht

führend in der Welt. [White

people rightly lead the world.]

|

|

Hostility

towards foreigners (V = HF; M = 1.48; SD = .71; n = 163; α = .77)

|

|

Es leben zu viele Ausländer

in Deutschland. [There are

too many foreigners living in Germany.]

|

|

Wenn Arbeitsplatze knapp

werden, sollte man die in Deutschland lebenden Ausländer wieder in ihre

Heimat zurückschicken. [If a shortage of jobs occurs, foreigners

living in Germany should be forced to return to their home country.]

|

|

Hostility

towards Muslims (V = HM; M = 1.48; SD = .77; n = 163; α = .73)

|

|

Durch die vielen Muslime

hier fühle ich mich manchmal wie ein Fremder im eigenen Land.

[Because of the

large number of Muslims living here, I sometimes feel like a stranger in my

own country.]

|

|

Muslimen sollte die

Zuwanderung nach Deutschland untersagt werden.

[Muslims should

be prohibited from immigrating to Germany.]

|

|

Hostility

towards asylum-seekers (V = HAS; M = 2.36; SD = .90; n = 167; α = .63)

|

|

Bei der Prüfung von

Asylantragen sollte der Staat großzügig sein.

[The state

should be generous in evaluating applications for asylum.]

|

|

Die meisten Asylbewerber

werden in ihrem Heimatland gar nicht verfolgt.

[Most asylum-seekers are not persecuted in

their home country.]

|

|

Devaluation

of Sinti and Roma (V = SR; M = 1.66; SD = .82; n = 175; α = .78)

|

|

Ich hätte Probleme damit,

wenn sich Sinti und Roma in meiner Gegend aufhalten.

[I would object to Sinti and Roma being in

my area.]

|

|

Sinti und Roma neigen zu

Kriminalität. [Sinti and

Roma have a tendency toward criminal behavior.]

|

|

Traditional

antisemitism (V = aSt; M = 1.23; SD = .48; n = 165; α = .48)

|

|

Juden haben in Deutschland

zu viel Einfluss. [Jews have

too much influence in Germany.]

|

|

Durch ihr Verhalten sind

Juden an ihren Verfolgungen mitschuldig.

[Jews are partly to blame for their

persecution because of their behavior.]

|

|

Modern

antisemitism (V = aSm; M = 1.76; SD = .73; n = 154; α = .76)

|

|

Viele Juden versuchen, aus

der Vergangenheit des Dritten Reiches heute ihren Vorteil zu ziehen.

[Many Jews try to take

advantage of the history of the Third Reich today.]

|

|

Bei der Politik, die Israel

macht, kann ich gut verstehen, dass man etwas gegen Juden hat.

[Due to the

politics of Israel, I can understand that people have something against

Jews.]

|

|

Was der Staat Israel heute

mit den Palästinensern macht, ist im Prinzip auch nichts Anderes als das, was

die Nazis im Dritten Reich mit den Juden gemacht haben. [What the state of Israel is doing with

the Palestinians today is basically the same as what the Nazis did with the

Jews in the Third Reich.]

|

|

Traditional

sexism (V = SXt; M = 1.36; SD = .67; n = 168; α = .70)

|

|

Für eine Frau sollte es

wichtiger sein, ihrem Mann bei seiner Karriere zu helfen, als selbst Karriere

zu machen. [For a woman it

should be more important to support her husband in his career than to pursue

her own career.]

|

|

Frauen sollten sich wieder

mehr auf die Rolle der Ehefrau und Mutter besinnen.

[Women should

return to the role of housewife and mother.]

|

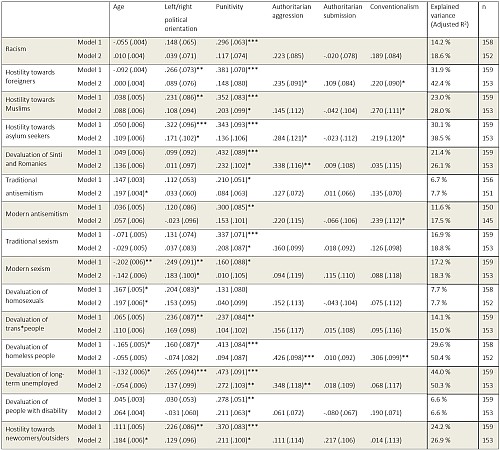

In the first regression models, punitivity

has a hypothesis-compliant significant effect across all elements (despite

devaluation of homosexuals). Respondents who harbor punitive educational

orientations consistently show higher values in

nearly all elements of GFE. Taking authoritarianism into account in the

following regression models, six elements still show significant

correlations: hostility towards Muslims (.203*),

devaluation of Sinti and Roma (.232*), devaluation of the long-term unemployed

(.272**), hostility towards newcomers/outsiders (.211*), traditional sexism

(.208*) and the devaluation of people with disabilities (.211*). This speaks

for the predictive power of punitive orientation on negative prejudices but we

can also see a close interplay of punitive and authoritarian orientations. If

the dimensions of authoritarianism are added, the effect of punitivity on some

GFE elements is reduced. At the same time, authoritarian aggression (which has

significant connections to the devaluation of Sinti and Roma, devaluation of

asylum seekers, devaluation of long-term unemployed, devaluation of the

homeless, and hostility towards foreigners) and conventionalism (with

significant links to hostility towards Muslims, devaluation of asylum seekers,

hostility towards foreigners, devaluation of the homeless and modern

antisemitism) are relevant factors influencing GFE. It is also noticeable that

no predictor has a significant relationship with GFE in two of the second

models (racism, devaluation of trans*people) but the whole model is still

significant in these cases. Therefore, we conclude that multicollinearity

between the different independent variables might play a role. In general the

punitive educational orientation does, however, have acceptable (but not too

high) correlations with the three dimensions of authoritarianism (.638** with authoritarian aggression; .584** with

submission; .474** conventionalism), showing that the constructs are

closely related but still distinct from each other.

The conceptualization of the relationship between authoritarianism and

punitivity still seems to be a desideratum and needs further theoretical and

empirical consideration. However, the empirical closeness of authoritarianism

and a punitive educational orientation further constitutes that this

educational orientation is in contradiction to humanistic educational ideals

like maturity, autonomy, and participation.

7

Conclusion

The results show that a punitive

educational orientation is positively related to antidemocratic attitudes in

the form of prejudices, and can also be seen as a predictor of them. Even after

the addition of theory-related constructs such as authoritarianism, punitivity

remains an explanatory variable for a number of prejudices. A close

relationship between punitivity and authoritarianism is evident but still needs

further analysis. Our analysis does have its limitations. Because we used a

convenience sample, we cannot generalize our results to society as a whole.

Furthermore, the data is cross-sectional and the analysis is, therefore, correlational, which precludes causal

testing of our hypotheses.

Our results are particularly relevant for

the gatekeeper function of social work, in that it functions as a bridge to the

welfare state and has involvement in implementation and concrete management of

the welfare state. If the former ideal of resocialization is abandoned in favor of a punitive orientation, this risks

actively devaluing the addressees of social work. In this way, social work

reproduces and reinforces precisely those relationships of power and domination

that social policy seeks to avoid. Our results indicate that a punitive

attitude and consequent practice can also be understood here as an

“antidemocratic educational practice” that promotes and supports social hierarchies,

is focused on normative conventions, and devalues vulnerable groups. It stands

in contrast to democratic ideals of equality and belonging. The analysis of

this change is, therefore, fundamental when considering citizenship. Punitivity

can serve here as a mechanism to clearly express who does not belong and who

does; who is equal and who is not.

References

Adorno, T. W.

(1982). Erziehung zur Mündigkeit. Frankfurt: Suhrkamp.

Allport, G.W.

(1954). The nature of prejudice.

Cambridge: Preseus Books.

Altemeyer,

B. (1981). Right-wing authoritarianism.

Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada: University of Manitoba Press.

Beierlein, C., Asbrock,

F., Kauff, M., & Schmidt, P. (2014). Die Kurzskala Autoritarismus

(KSA-3): Ein ökonomisches Messinstrument zur Erfassung dreier

Subdimensionen autoritärer Einstellungen. Zusammenfassung

sozialwissenschaftlicher Items und Skalen. Retrieved August 2019, from: https://zis.gesis.org/pdfFiles/Dokumentation/Beierlein_Kurzskala_Autoritarismus_v1.01.pdf

Benner, D. & Brüggen,

F. (2004). Mündigkeit. In D. Benner & J. Oelkers (Eds.), Historisches

Wörterbuch der Pädagogik (pp. 687-699). Weinheim, Basel: Beltz.

Clark, Z., &

Schwerthelm, M. (2017). Manualisiertes Strafen oder demokratisches

Verzeihen? Von den Möglichkeiten und Bedingungen des Verzeihens in der

stationären Heimerziehung. Sozial Extra, 41(5), 15-18.

Dollinger, B. (2008). Problem attribution and intervention. The interpretation of

problem causations and solutions in regard of Brickman et al. European

Journal of Social Work, 11(3), 279-294.

Dollinger,

B. (2011a). Punitivität in der Diskussion. Konzeptionelle,

theoretische und empirische Referenzen. In B. Dollinger & H.

Schmidt-Semisch (Eds.), Gerechte Ausgrenzung? Wohlfahrtsproduktion und die

neue Lust am Strafen (pp. 25-73). Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für

Sozialwissenschaften.

Dollinger, B.

(2011b). Punitive Pädagogen? Eine empirische Differenzierung von Erziehungs-

und Strafeinstellungen. Zeitschrift für Sozialpädagogik, 9(3), 228-247.

Dollinger, B.

(2017). „Sicherheit“ als konstitutive Referenz der Sozialpädagogik.

Begriffliche und konzeptionelle Annäherungen. Soziale Passagen, 9(13),

213-227.

Dollinger, B., &

Raithel, J. (2005). Problematisierungsformen sozialpädagogischer Praxis:

Eine empirische Annährung an Einstellungen zu sozialen Problemen und ihrer

Bearbeitung. Soziale Probleme, 16(2), 92-111.

Häßler, U., & Greve,

W. (2012). Bestrafen wir Erkan härter als Stefan? Befunde einer

experimentellen Studie. Soziale Probleme, 23(2), 167-181.

Klein, A., & Groß, E.

(2011). Gerechte Abwertung? Gerechtigkeitsorientierungen und ihre Implikationen

für schwache Gruppen. In B. Dollinger & H. Schmidt-Semisch (Eds.), Gerechte

Ausgrenzung? Wohlfahrtsproduktion und die neue Lust am Strafen (pp.

145-165). Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Kury, H., Brandenstein,

M., & Obergfell-Fuchs, J. (2009). Dimension of

punitiveness in Germany. European Journal on Criminal Policy and Research,

15(1-2), 63-81.

Lautmann,

R., & Klinke, D. (2004). Punitivität

als Schlüsselbegriff für eine Kritische Kriminologie. Kriminologisches

Journal. Beiheft, 36(8: Punitivität), 9-29.

Lutz, T. (2017).

Sicherheit und Kriminalität aus Sicht der Sozialen Arbeit: Neujustierungen im

Risiko- und Kontrolldiskurs. Soziale Passagen, 9(2), 283-297.

Lutz, T., & Ziegler,

H. (2005). Soziale Arbeit im Post-Wohlfahrtsstaat - Bewahrer oder

Totengräber des Rehabilitationsideals? Widersprüche: Zeitschrift für

sozialistische Politik im Bildungs-, Gesundheits- und Sozialbereich, 25(97),

123-134.

Mansel, J. (2004).

Wiederkehr autoritärer Aggression. Soziale Desintegration und gruppenbezogene

Menschenfeindlichkeit. Kriminologisches Journal. Beiheft,

36(8: Punitivität), 105-137.

Markusen,

A. (2003). Fuzzy concepts, scanty evidence,

policy distance: The case for rigour and policy

relevance in critical regional studies. Regional Studies, 37(6-7),

701-717.

Matthews,

R. (2005). The myth of punitiveness. Theoretical

Criminology, 9(2), 175-201.

Mohr, S. (2017). Abschied

vom Managerialismus. Zum Verhältnis von Organisation und Profession in der

Sozialen Arbeit. Bielefeld: Universität Bielefeld. Retrieved May 2019,

from: https://pub.uni-bielefeld.de/record/2908758

Mohr, S., & Ziegler,

H. (2012). Professionelle Haltungen, sozialpädagogische Praxis und

Organisationskultur. Schriftenreihe EREV, 53(2), 20-30.

Mühler, K., &

Schmidtke, C. (2012). Warum es sich lohnt, Alltagstheorien zum Strafen

ernst zu nehmen: zur Vermittlung zwischen autoritären Einstellungen und

Strafverlangen. Soziale Probleme, 23(2), 133-166.

Oelkers, N.

(2013). Punitive Haltungen in der Sozialen Arbeit. Kontroll- und

Straforientierungen im Umgang mit Abweichenden und Wohlfahrtsempfängern bei

Studierenden der Sozialen Arbeit. Sozial Extra, 37(9-10), 34-38.

Oesterreich,

D. (2005). Flight into security: A new approach

and measure of the authoritarian personality. Political Psychology,

26(2), 275–298.

Pangritz,

J. (2019): Fürsorgend und doch

hegemonial? Zum Verhältnis von Männlichkeit, Feminisierung und Punitivität in

pädagogischen Kontexten. Gender (forthcoming)

Stehr, J. (2014).

Repressionsunternehmen Konfrontative Pädagogik. Vom Versuch, Soziale Arbeit zu

einer Straf- und Unterwerfungsinstanz umzubauen und dies als Hilfe und

Unterstützung zu verkaufen. Sozial Extra, 38(5), 43-45.

Wacquant,

L. (2009). Punishing the poor. The neoliberal

government of social insecurity. Durham, London: Duke University

Press.

Zick, A., & Klein, A.

(2014). Fragile Mitte – Feindselige Zustände. Rechtsextreme Einstellungen in

Deutschland 2014 (published on behalf of the Friedrich Ebert Foundation by Ralf

Melzer). Bonn: Dietz.

Zick, A., Küpper, B.,

& Berghan, W. (2019). Verlorene Mitte – Feindselige Zustände.

Rechtsextreme Einstellungen in Deutschland 2018/19 (published on behalf of

the Friedrich Ebert Foundation by Franziska Schröter). Bonn: Dietz.

Zick, A., Kupper, B.,

& Krause, D. (2016). Gespaltene Mitte – Feindselige Zustände.

Rechtsextreme Einstellungen in Deutschland 2016 (published on behalf of the

Friedrich Ebert Foundation by Ralf Melzer). Bonn: Dietz.

Zick, A., Wolf, C., Küpper,

B., Davidov, E., Schmidt, P., & Heitmeyer, W. (2008). The syndrom of group-focused enmity: The interrelation of prejudices

tested with multiple cross-sectional and panel data. Journal of

Social Issues, 64(2), 363-383.

Ziegler, H., &

Scherr, A. (2013). Hilfe statt Strafe? Zur Bedeutung punitiver

Orientierungen in der Sozialen Arbeit. Soziale Probleme, 24(1), 118-136.

Author’s Address:

Johanna Pangritz,

MA, Dipl. Päd.

Bielefeld

University, Germany

Faculty of

Educational Science, Institute for Interdisciplinary Conflict and Violence

Research

johanna.pangritz@uni-bielefeld.de

Author’s Address:

Wilhelm Berghan, MA

Educational Science

Bielefeld

University, Germany

Faculty of

Educational Science, Institute for Interdisciplinary Conflict and Violence

Research

wberghan@uni-bielefeld.de