What is Practice Research in Social Work - Definitions, Barriers and Possibilities

1 Introduction

The basic foundation of practice research is building theory from practice and not only from academia. The approach is based on a combination of research methodology, field research and practical experience.

In most cases in social work it is impossible to examine and initiate a research process solely from a researcher‘s point of view, because he or she is always under the influence of the political and institutional context that frames the phenomenon or the issue in focus. In the words of Gredig and Sommerfeld: ‘If we want scientific knowledge, and especially empirical evidence, to play an effective role in professional action, then we have to focus on the contexts where the processes of generating knowledge for action actually take shape, that is, on the organizations engaged in social work.’ (Gredig and Sommerfeld 2008:296). The starting point of this article is that research closely connected to, and under the influence of, practice, with the aim of improving such practice, is of the same high quality as research characterised by distance between researcher and the subject. The interface between practice and research, and the degree to which these processes mutually interfere, are even more important than in other research processes.

Throughout the past 10 years, practice has been confronted with increasing demands to measure outcomes of public support (Osborne 2002, Heinrich 2002). Buzz words such as documentation, effect and evidence-based practice have become part of everyday social work – both to help politicians and administrative leaders manage growing economic problems and simply to acquire further knowledge about the results of social workers doing social work: what works for who under which conditions. This is stated in the core values of the department of social services in the municipality of Aalborg, Denmark: ‘Assessment of coherence between effort and results are common evaluation principles’ (my translation) (Kjærsdam 2009). This political and administrative focus has put research at the centre of developing social work. The focus has led not only to interest in managing budgets in social work but also to an interest in more knowledge-based – not only experienced-based – development of both social work as a profession and individual social workers. This is to produce new knowledge and learning strategies on a scientific foundation and in close collaboration with local needs. Thus the demand to reveal outcomes of public support and the modern growth of complexity and uncertainty in society (Nowotny, Scott & Gibbons 2001:47) support the development of new kinds of knowledge production in practice.

Another point of the “new” knowledge production is that it is based not only on more general and large-scale research but also on locally based research and/or evaluation. These kinds of research projects are intended to bolster learning processes in which managers and social workers become partners in research instead of only consumers of it. As a manager in the municipality of Aalborg, Denmark, remarked: ‘Findings from research and evaluation must be discussed with employees with reference to the learning process and to continuing development’, and: ‘the need for evidence-based knowledge has to be ensured in a collaboration process with partners with relevant research competence’ (my translation) (Kjærsdam 2009). In areas where the research perspective has been dominant and exclusive for many years, the learning – or collaboration – process involves a shift in attitude to not only discussing research findings but also to discussing the effects of findings as well as trying out findings in practice throughout the research process.

The development and expressed needs within practice strongly indicate a growing need for measuring public support and for advancing knowledge-based learning processes in a close collaboration with education and science based research. Development in Denmark has shown that although some municipalities build up small research departments, they also need “outsiders” to measure and evaluate public support. These outside research partners must be open minded towards allowing practice to join the research process – from producing research questions, through data collection and analysis, to the information and the transformation of findings into new methods in social work.

2 Science of the Concrete, Mode 2 Knowledge Production and Practice Research

I will argued throughout this article, that social work research, practice and education are very well suited to practice research. To define, understand and elaborate practice research in social work, it is necessary to involve definitions of connected approaches and theory.

A natural connection that widens the understanding of practice research is what the Danish researcher Bent Flyvbjerg refers to as “the science of the concrete” (Flyvbjerg 1991). That is a bottom-up knowledge production, or a field of research oriented towards subjects more than objects. To restore social science to its rightful place in contemporary society, Flyvbjerg suggests that researchers return to classical traditions of social inquiry and reorient practice towards what he defines as “phronetic social science” (Flyvbjerg 2001). Flyvbjerg defines the science of the concrete as pragmatic, variable, context-dependent and praxis-oriented science (Flyvbjerg 2001:57). It operates via practical rationality based on judgement and experience (Flyvbjerg 2001:58), in which some key elements are getting close to reality (the research is conducted close to the phenomenon studied and is subject to reactions from the surroundings, and remains close during the phases of data analysis, feedback and publication of results), emphasizing little things (the focus is on minutiae, where research studies the major in the minor and where small questions often lead to big answers), looking at practice before discourse (discourse analysis is disciplined by analysis of practice, and research focuses on practical activities and knowledge in everyday situations), studying concrete cases and contexts (research methodologically builds on case studies, because practical rationality is best understood through cases; practices are studied in their proper contexts), joining agency and structure (focus is on both actor and structural level; actors and their practices are analysed in relation to structures, and structures in terms of agency) and finally dialoguing with a polyphony of voices (the research is dialogical and includes itself in a polyphony of voices, with no voice claiming final authority) (Flyvbjerg 2001:132–139). According to Flyvbjerg, theory has a minor position and context a major one in phronetic social science. Flyvbjerg does not criticize rules, logic, signs and rationality – in fact, he states that it would be equally problematic if these elements were marginalized by the concrete. However, he criticizes the dominance of these phenomena to the exclusion of more context- and practice-based phenomena (Flyvbjerg 1991:46, Flyvbjerg 2001:49). As the above-mentioned key elements suggest, Flyvbjerg emphasizes that dialogue has a central position in actual science – dialogue with those who are studied, with other researchers, and with decision-makers as well as with other central actors in the field. From this position, research cannot provide straight and simple answers as often seen in more traditional research processes. He stresses that ‘no one is experienced enough or wise enough to give complete answers’ (Flyvbjerg 2001:61). The task of phronetic social science is not to provide simple answers or statements but ‘to clarify and deliberate about the problems and risks we face and to outline how things may be done differently, in full knowledge that we cannot find ultimate answers to these questions’ (Flyvbjerg 2001:140).

Flyvbjerg is not emphasizing science of the concrete or phronetic social science to the exclusion of natural science but stressing that society needs not only natural science but also phronetic-oriented social science to investigate fully developments and processes in modern societies. He argues that both natural and social sciences have their own strengths and weaknesses, depending on subject matter, and that social scientists therefore need to reflect much more on these differences, making it possible to capitalize or build on their strengths, rather than to mimic vainly their natural science counterparts. He puts it this way: ‘Where natural sciences are weakest, social science is strong’ (Flyvbjerg 2001:53), and:

Just as social sciences have not contributed much to explanatory and predictive theory, neither have the natural sciences contributed to reflexive analysis and discussion of values and interests, which is the prerequisite for an enlightened political, economic, and cultural development in any society, and which is at the core of phronesis (Flyvbjerg 2001:3).

From this position, practice research may very well be a way to transform phronetic social science into everyday practice as well as phronetic social science constituting both a theoretical and a methodological framework for practice research in social work.

Another natural element of practice research is the connection with mode 2 knowledge production. While mode 1 knowledge production is defined as building upon traditional research approaches guided only by academic norms, mode 2 knowledge production is characterised by application-oriented research where both frameworks and findings are discussed and evaluated by a number of partners—including laypeople—in public spheres (Kristiansson 2006).

Mode 2 knowledge production takes place in an interaction between many actors, each and every one of whom represents different interests and contributes a variety of competences and attitudes. It is characterised by a relatively flat network- and collaboration-oriented structure marked by organizational flexibility, and shows no sign of becoming institutionalized in conventional patterns (my translation) (Kristiansson 2006:18).

The number of researchers will expand from a few privileged people to a mixed group in the production of knowledge. ‘Other actors once dismissed as mere “disseminators”, “brokers” or “users” of research findings, are now more actively involved in their “production”’ (Nowotny, Scott & Gibbons 2001:89). In this way, mode 2 research is bottom-up rather than top-down oriented (Nowotny, Scott & Gibbons 2001:113).

The reason why mode 2 knowledge production and research has gained interest, according to Kristiansson, is the increasing attention to research and its influence on society. This attention has created increasing interest in research into both political and social issues as well as solutions and understanding based on different disciplines instead of a single discipline. As summarized by Gibbons et al., ‘Mode 2 knowledge is created in broader transdisciplinary social and economic contexts’ (Gibbons et al. 1994:1).

According to Kristiansson, there are a variety of interests within mode 2 knowledge production and research that constitute different expectations of, and demands on, knowledge, development, research design and findings. Different interests in practice research are discussed below in this article. Instead of solving possible conflicts among different stakeholders, mode 2 acts within and together with them. That is, collaboration and partnership extend from the very beginning to the very end. In this way, knowledge production ‘arises in the light of a specific logic which participants must develop in common to be able to act together and towards the problem’ (my translation) (Kristiansson 2006:19). In this way, mode 2 is in contrast to traditional research evaluated solely by peers and it is collaborative, evaluated both by peers and – as Kristiansson puts it – by a crowd of assorted partners with different agendas. To develop mode 2 knowledge production, all partners must accept ongoing reflection on differences.

Kristiansson also emphasizes that mode 2 is characterised by a new type of knowledge especially connected to practice. Like phronetic research, mode 2 research challenges traditional understanding of knowledge production

Mode 2 research is, in brief, characterized by its focus on solving problems in specific contexts of practice. In this way, research is controlled by specific tasks, not by the free choice of the researchers. Mode 2 research is application oriented, and oriented more towards generating solutions than towards generating new knowledge (my translation) (Rasmussen, Kruse & Holm 2007:124).

As Rasmussen, Kruse and Holm put it, mode 2 research is only valid if individuals or groups of people in the specific practice concerned find the results applicable and useful.

As the descriptions and definitions of phronetic social science and mode 2 knowledge production suggest, there seem to be several movements in the same direction in modern society towards more context-based, dialogue-oriented and partnership-focused research and knowledge production. Practice research in social work is closely connected to, and based on, this orientation and – as the rest of this article will show – translates abstract and theoretical concepts into more concrete definitions and practice.

3 Approaches to practice research

In discussions of practice research, it is often unclear what it consists of. As Pain writes in a review of practice research: ‘Despite the many years of research into practice (Gibbons 2001) and debate concerning it, there is still a lack of consensus about what practice research includes and what lies outside its boundaries, and there are continuing debates about paradigms and methods, collaboration and ethics’ (Pain 2008:1).

Before discussing different approaches in practice research it is important to state that discussion of practice research is much more important than a limited definition. The definitions and frame-works considered in this article are not attempts to narrow the discussion and the practice research experiences. On the contrary, it is an invitation to – from a level of common understanding and “set off´s” – strengthen the discussion and the development of practice research.

It seems that two approaches to practice research – approach A and approach B – can be identified.

In approach A the focus is on the framework, goals and outcomes of the research process. The starting point is that it is necessary and desirable that there should be a close – and often locally bound – collaboration between practice and research, with mutual commitment. It is not crucial who collects data or performs the analysis, although it is under the management of trained researchers and institutions.

It is difficult to ascertain how collaboration between practice and research in practice research may be organized generally, as it must begin with locally based organizations and issues that probably change from time to time. A recent statement on practice research produced following the “Practice research: developing a new paradigm” conference said:

Practice research involves curiosity about practice. It is about identifying good and promising ways in which to help people; and it is about challenging troubling practice through the critical examination of practice and the development of new ideas in the light of experience. It recognizes that this is best done by practitioners in partnership with researchers, where the latter have as much, if not more, to learn from practitioners as practitioners have to learn from researchers. It is an inclusive approach to professional knowledge that is concerned with understanding the complexity of practice alongside the commitment to empower, and to realize social justice, through practice (Salisbury Statement 2009:2–3).

Practice research in this approach cannot be research which is planned, conducted and “delivered” by a researcher to practitioners. The main point is that practice and research develop every part of the collaboration together because practice research must be in tune with all participants. It also means that collaboration can appear differently and may change in the following ways. 1) The research could be planned and discussed by researchers and practitioners but carried out by researchers. 2) The research goals and questions could be set, and they could be discussed throughout the process and be part of a learning process where both researchers and practitioners participate all through it. 3) Research could be part of an ongoing research process in which it is hard to distinguish learning processes and research/examination processes.

From these characteristics practice research in approach A can be defined as:

-

critical and curious research that describes, analyses and develops practice;

-

research based on generally approved academic standards;

-

research built on experience, knowledge and needs within social work practice;

-

research where the responsibility for the research is entrusted to generally approved research institutions;

-

close, binding and locally based collaboration between researchers and practitioners in planning, completing and disseminating the research;

-

research where findings are closely connected to learning processes in practice;

-

participatory and dialogue-based research relevant to developing practice and validating different areas of expertise within the partnership; and

-

research that produces, analyses and describes specific issues in both empirical and theoretical general coherence.

This approach does not exclude practitioners from the research process. On the contrary, practitioners are often included at different levels in the research process and as researchers, but trained researchers still bear responsibility for research quality. The focus is not on the role of the researcher but on the content of the research. It is “to use the best from both parts” in a respectful collaboration. One could say, with the words from the Salisbury Statement (Salisbury Statement 2009:4), that the foundation of the approach is practice-minded researchers and research-minded practitioners. Or in the words of Blumenfield and Epstein: ‘Under the right organizational conditions, with the right kinds of support and consultation and a “practice-based research” perspective, social work practitioners can actively and enthusiastically engage in research that has implications for their own practice and for practice in other settings’ (Blumenfield and Epstein 2001:3).

The approach is open and inclusive instead of closed and exclusive. It is focused on knowledge production and learning processes in social work practice and research as a whole instead of mainly on processes within chosen practices.

In approach B practice research is defined as research, evaluation and investigation conducted by practitioners. This approach primarily focuses on the roles of the researchers. Although different it is based on a definition that is similar or identical to practice research in the first approach. According to Epstein: ‘Practice-based research may be defined as the use of research-inspired principles, designs and information gathering techniques within existing forms of practice to answer questions that emerge from practice in ways that will inform practice’ (Epstein 2001:17). However, connected to this, it is said that ‘practice research … is a phenomenon that occurs when practitioners commit themselves to something they call research in their own practice while they, at the same time, practice social work’ (my translation) (Ramian 2003:5). This distances approach B from approach A as practitioners are expected to always be active researchers. The difference is even more specific when Ramian defines six features in the perception of the phenomenon of practice research (Ramian 2003:5) (my translation):

-

It is conducted by practitioners at work using at least 80% of their working hours as practitioners.

-

The research questions focus on problems connected to everyday practice.

-

Common recognized scientific methods are used.

-

Projects are made feasible.

-

Findings are communicated to other practitioners.

-

The research field is in practice.

Following from these six features, Ramian identifies the practice setting as the research institution (instead of the university), a view supported by Rehr, who says that practice-based research studies are practitioner led (Rehr 2001). Ramian underlines this: ‘the practice researcher adjusts his or her strategy and methods in ways that make it possible to conduct research activities in practice’ (Ramian 2003:6). According to Ramian, (research) practitioners have an interest in, and are de-pendent on, finding solutions to problems in practice, while traditional researchers are busy meeting the requirements for validity of the research (Ramian 2009). Ramian points out that the reduced gap between research and practice that occurs when practitioners carry out research increases the possibility of producing knowledge relevant to practice and applying findings to practice. Ramian also points out that findings from practice research are not presented in typical academic journals but rather through media such as conferences and seminars (Ramian 2003). Ramian has lately defined his research approach as “Research Light” – investigations with a narrow and specific focus that may be completed in 5–10 days by practitioners with few research skills but involved in a “collaborative practitioner research network” (Ramian 2009). By this Ramian distinguishes “research light” from what he calls large-scale research as well as longitudinal research and research in depth. These kinds of research, according to Ramian, must be conducted by trained researchers but build on findings from research light (Ramian 2009).

At this point, approaches A and B agree, but it is vital that approach A should attach importance to the responsibility of trained researchers for the research process, whether light or heavy. According to Ramian, practitioners need not be trained researchers but they must be introduced to research methods. A collaborative practitioner research network must be established to support the practitioner researchers during the process. Although there are some similarities, the two approaches appear to diverge at this point, as approach A entails that the responsibility for research projects will be carried out by trained researchers.

One problem in the definition of practice research in approach B seems to be that traditional research resembles old-fashioned social or natural science. Harmaakorpi and Mutanen (2008) point out in an argument for more practice-based innovative processes that ‘the experts in innovation processes cannot just pour knowledge into the innovation partners and then disappear from the scene’ (Harmaakorpi and Mutanen 2008:88). This criticism could very well be used to promote approach A as well, because this approach is characterised by innovative collaboration processes from defining research questions to the analysis of data. Both approaches emphasize the differences between research and practice, but while in approach A the differences are seen as natural and inspiring parts of the collaboration and the research process, in approach B they appear to be locked irreconcilable positions, and researchers are characterised as unwilling to consider the needs and traditions of practice. While Harmaakorpi and Mutanen stress that partners require common interests and intentions determined by practical context, approach A stresses that the partners need to “do what they are best at” and that no partner can determine what is right: that is, the struggle between the different interests is the strongest potential within the collaboration. (For further discussion, see below). Referring to the discussion of modes 1 and 2 above, it seems that approach B researchers understand researchers from approach A (for example from universities) as having a top-down focus, traditional orientation and being guided only by academic norms. These characteristics identify approach A researchers with a mode 1 position. From the perspective of approach B researchers, approach A researchers are unable to move from mode 1 towards mode 2. At the same time it seems that both approach A and B researchers understand themselves as connected to a mode 2 position.

To prevent unnecessary conflict between the two positions about the same notion and to maintain the differences, it may be helpful to define them in the following way:

-

Research that focuses on collaboration between practice and research (approach A) is defined as practice research

-

Research that focuses on processes controlled and accomplished by practitioners (approach B) is defined as practitioner research

A third approach may be mentioned here. It could be connected to practitioner research as it focuses specifically on user participation in research processes – and in that way also more on roles than on content in the research process. The discussion of this – although interesting and necessary – research approach is left out in this article as the position includes not only practice research but all kinds of research activities. The discussion about involving users in research processes is important, but it is not specifically connected to practice or practitioner research. It is a general issue for all kinds of scientific work. Practice and practitioner research can involve users or can be conducted without them, but it is important to have the discussion and to make a decision concerning user involvement in the research process in all research initiatives. In continuation of the above mentioned definitions this third approach could be defined as:

-

Research that focuses on user participation in the research process is defined as user-controlled research.

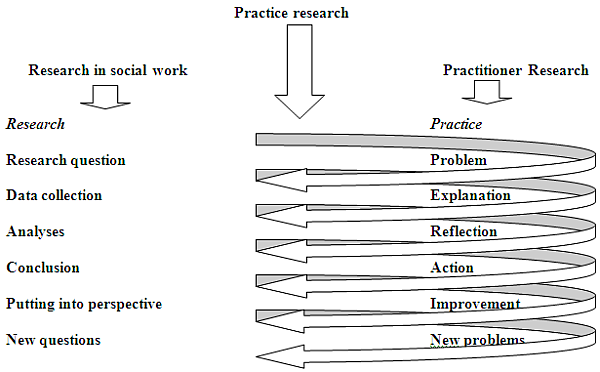

Practice research is located on a continuum between “traditional” research in social work and practitioner research or from research to practice. The figure below shows both the differences and the similarities between research processes and practice processes in social work. Although the stages in the processes can be compared the content of the stages are different as well as the outcome of the processes and it places practice research somewhere in between these two extremities. Research in social work – although necessary to social work – is not a part of learning and development processes in social work, while practitioner research is directly connected to the performance of social work practice. In performing research in social work it is not necessary to establish a partnership between research and practice – as emphasized in the definition of practice research above. In practice research the traditional stages of research are also followed, but are connected to the parallel stages in practice processes. For instance, the research question cannot be generated without connecting it to actual problems in practice (as well as data collection, analyses, conclusions, perspectives), and new questions cannot be generated without connecting and involving explanations, reflections, actions, improvements and new problems from practice.

The diagram below illustrates the way in which posing a research question in practice research is followed by taking in and understanding the kinds of problems with which practice deals. It also illustrates how this interaction with practice will probably change the research question and/or make it clearer and more connected to everyday problems in practice. This iterative process is represented by the spiral movement of the process.

Practice research is both part of traditional research processes and part of processes in practice and can easily include practitioner research or research light – but it has its own position in between research in social work and practice.

4 Different interests in practice research

Although I have argued that both practice and research have an interest in collaboration in research processes, this is not tantamount to a total convergence of all areas in the field. On the contrary it is useful to be aware of contradistinctions that cannot be neutralized. It seems that an ideal to establish an unproblematic collaboration among research, education and practice in social work has developed. This ideal could be considered an immediate strength, but in the long run, it endangers both research and practice. It is not possible to establish an unproblematic collaboration. The desire for, and the ideal of, the unproblematic collaboration entails the risk that research, education and practice will become toothless – they will, to put it bluntly, risk falling to the lowest common denominator. There is an essential difference between a researcher and a practitioner: the researcher views research as a goal in itself, while the practitioner views research as means. To the researcher, research and the research process are the main objectives. The practitioner‘s goal is to present initiatives and viable solutions to social problems. This does not mean that the interests of research and practice are necessarily different but that researchers and social workers must remember the difference in interests between them. The struggle between partners and conflict between the two fields has a dynamic and creative function.

There are also other stakeholders and therefore more contradictions that arise when opening up participation in practice research. The view and concerns of all these actors have to be taken into account within any practice research project. Some of the tensions and challenges arising from the involvement of these different parties will be discussed below.

The main stakeholders in practice research are:

-

Social workers;

-

Users;

-

Administrative management and organizations;

-

Politicians; and

-

Researchers.

Social workers are bound to a political, organizational and professional context. It is not possible for social workers solely to satisfy their own values or needs expressed by users. The legislation stipulates possibilities and obligations; the resources and the social worker authority are often covered by legislation; administrative and/or political management in social work often influence interpretation and application; local authorities, politicians and civil servants interpret the legislation that organizes and structures social work differently in various organizations and municipalities. Finally, social workers‘ educational background, professional values and ideals influence the way social work is implemented in practice. Professional values and ideals that may appear in contradistinction to some extent to user needs and to organizational frameworks.

Users have a natural interest in receiving the best support possible. Although many users hope that their participation in studies of social work may help them qualify, for example, for public support (Uggerhøj 1995), their attention will be on receiving the best researched support for their own individual and specific problems. A study on user experience and pedagogical treatment in a Danish institution that deals with families at risk suggests that users judge the intervention differently according to the severity of their problems (Uggerhøj 2000).

Generally, administrative management and organizational frameworks are influenced by politically defined boundaries, local cultures and political traditions. Moreover, the desire of social work management and organizations to “establish order in chaos” concerning user problems and to appear responsible and rational may conflict with users‘ and social workers‘ desires to focus on their individual issues and understanding of the issues. These desires are based on the users‘ own understanding instead of a rational public understanding. Management needs – together with political requests for more documented and effective social work – often lead to a focus on evidence-based knowledge production and research instead of other research approaches.

Politicians focus on tools to measure the effects of political decisions and to explain them to citizens. The individual needs of users and descriptions of collaboration processes in social work have less importance, because these are often considered to be the concern of an individual user or included in a particular social worker‘s professional competence.

Researchers‘ approaches are influenced by their own research area and needs as well as university management‘s requirements to justify themselves in the academic field. Research areas and academic needs do not always converge with the needs and requirements of social work practice. The demand for publication in peer-reviewed periodicals with detailed and traditional criteria for research, content and article structure may conflict with the needs for information in practice. Furthermore, the scientific need for distance from the subject of research may appear to conflict with the necessity for practice in proximity. The scientific ideal of objectivity and an unwillingness to influence practice conflicts with the need of practitioners to influence and include research in developing practice – an interesting and difficult contradiction.

The different stakeholders cannot and must not necessarily combine completely, but it is crucial that practice research constitutes a series of contradistinctions and confluences, which entails dilemmas that both research and practice must address. The different interests are important to all partners and significant for society as well. They are so important and significant that functioning well depends on the possibility of retaining these different interests. Instead of attempting to balance or reconcile these differences, it is important to enlighten the differences if collaboration is to be established. Moreover, in this way, it is possible for different actors to gain greater understanding of each other and their respective interests. Dilemmas are not resolved but must be included in the practice research process.

Research finds itself in the most powerful position and thus has a special obligation to promote awareness of different interests, exactly as the powerful position of social workers with regard to users gives them a special obligation to use it in a positive way in their relationship.

My claim is that researchers have a special position and responsibility to respond to these contradistinctions. It is thus evident that the possibility of a dialectical approach is based on differences and contradistinctions that are crucial to the raison d‘être of the partners and that enable them to challenge each other. From this position, my claim is also that a researcher could or should never become a practitioner, or vice versa. However, this does not mean that efforts should not be made to utilize these differences to inform social work. Dilemmas and contradictions are a key to develop new and useable research in social work and to support a knowledge production build on every partner instead of primarily one.

5 Practice research – an example

In Denmark, a pilot practice research project has been launched. Experience from the process of establishing the project shows that it takes a long time for the stakeholders to obtain a common understanding – but also that this time is needed if the different ends are to be met.

The goal of the project is, over a period of five years, to boost collaboration between research, education and different municipalities, focusing on the development of knowledge-based practice. The project will be evaluated and from the findings and the experiences of the process a frame for practice research in a collaboration between municipalities, regions, educations and research is supposed to be presented.

The point of the project is to take the needs of all stakeholders seriously by supporting their different needs and goals. From meetings between the stakeholders in the project it is clear that there are different needs and goals. Political and administrative leaders want both to know more about the effectiveness of social work and to establish a more knowledge-based practice. Both requirements are difficult to fulfill within the frames of day to day social work. Social workers want to both stay within the framework of knowledge gained whilst qualifying and to obtain further training. Research shows that social work knowledge is often de-coded whilst working in practice (Uggerhøj 1995, Uggerhøj 2002). The rational organizational setting of practice, the complexity of social problems and the stress of everyday social work often make it difficult for social workers to retain their original ideas and skills gained at qualification. To re-code and develop knowledge social workers need to be challenged by analysis and findings not only connected to the effectiveness of social work but also to developing theories, methods and skills in social work. Educators need to constantly develop social work theories, methods and their own teaching. Both in ways of developing skills that makes it possible for social workers to meet the complex and concrete world of social work in different institutional settings and to present theories and methods that stand the test of time. Researchers need to try out research questions, to challenge traditional research methods and to make findings transformable to “the real world”. This can not be obtained solely by evaluating and documenting practice. It also requires more theoretical research and more longitudinal and comparative studies. (In the Danish project service users have not been involved in creating the design of the practice research project, but if they had been it’s likely that new kind of needs and goals would be added concerning the ongoing development for both users as a group and for the individual user).

If these different needs are not met in the project one or more of the stakeholders will withdraw, become a ghost-partner or even oppose the initiative. At the same time the project needs to be connected instead of divided into different autonomous projects. To consider how to balance these needs the stakeholders met for an extended period to learn more about each other and their different needs. Through this process the project came alive as both the different and the common needs informed the developing description of the research design. The joint design gave rise to both broader research questions covering both short term evaluations, and longitudinal, theoretical and more abstract studies. Through this process the stakeholders elaborated the following contract and common understanding:

To establish ongoing and specific relations among practice, research and education through a project where the purpose is to identify activities that:

-

enhance practice qualifications exercised within regional or municipality settings;

-

establish a research-based development of practice;

-

create a platform for research in practice within the field of social work;

-

establish exchange of experiences among specific practice and relevant education;

-

establish relevant training and education within the area of social work; and

-

develop new types of research, education, and practice. (my translation) (Ebsen and Uggerhøj 2007:3)

Along the way the project was discussed with social workers and politicians in the two participating municipalities as well as with researchers and educators at the university. Additionally the project was introduced to potential outside partners – e.g. other possible competitor research departments and ministerial departments who could create an economical foundation of the project. Through these presentations and negotiations the common understanding within the project was strengthened and the description of the projected was being specified. The project has obtained both encouragement and support from all outside partners – but not yet economic support. It has been a long journey for practice partners. The question arises whether a shorter process of discussion and development would have made it possible for the different stakeholders to understand and respect their different needs. However, one central experience from the project is that practice research needs time to air their different perspectives in a respectful and proper manner.

6 To walk hand in hand without becoming lovers

Practice research is necessary in the ongoing development of social work, but it is also a meeting point for different views, interests and needs, where complexity and dilemmas are inherent in the collaboration and challenge of both practice and research. Practice research in social work cannot develop from either practice or research alone but from both together.

My position with regard to change and development in practice research in social work and to collaboration between researchers and practitioners is therefore based on the Marxian process of “change through the conflict of opposing forces” (The Free Dictionary by Farlex) and not the Hegelian process of “arriving at the truth by stating a thesis, developing a contradictory antithesis, and combining and resolving them into a coherent synthesis” (The Free Dictionary by Farlex) meaning that contradictions are abolished and new realizations emerge.

If practice research is to be included in knowledge production and practice, it must become part of processes in practice as well as being part of traditional research processes. Research cannot remain on the sidelines and leave the collaboration with practice once data collection and analyses are complete. Research must be involved in providing information. For example, it must educate practitioners in new social work methods/tools, or in new and different ways of carrying out social work, and it must be involved in turning theoretical and analytical findings into useable tools in everyday social work – be a part of learning processes in practice. Moreover, representatives of practice need to be involved or at least to accept that practical issues must be turned into theoretical issues or propositions, and must be involved in developing methods for practice research. It is necessary for both sides to be open-minded and to learn from each other. Not only will practice learn from research but also research will learn from practice which will inform and develop research and research methods.

The challenge from research to practice is to examine existing truth and common understanding: the social worker doxa (Bourdieu 1972, Bourdieu 1982), to establish awareness and elucidate phenomena, actions and considerations to which the practitioners tend to be blind – precisely because they are in practice. From this point of view, it is less challenging simply to describe and measure effects of everyday social work practice. My goal is not to deny that it is interesting to carry out studies on social work and its effects, but such research does not necessarily challenge practice, research and society, as it risks focusing only on insight within practice. Thus, too close a connection and understanding between research and practice is futile and may hinder the emergence of new knowledge.

The challenge from practice to research is to support or provoke research to become more creative in understanding practice built on complexity, and to act flexibly instead of constructing a paradigm suitable for research. It should also challenge research to be aware of elements of power in both social work and research processes. From a practice point of view, research improves the comprehension of everyday problems as well as encouraging more informed solutions to these problems. This approach challenges the scientific tendency to view a phenomenon from an abstract and theoretical position. The theoretical and analytic approach is pivotal in the “science war” within basic research, which has – frankly speaking – attributed high status to abstract approaches, and low status to the practical. Thus, practice will challenge research right at the heart, as some researchers will look upon this as research being in danger of losing its basis and identity. Social work is marked by human beings‘ different reactions to the same problem. Hence, research in social work has to be able to establish studies of this action-oriented field and the built-in differences between research and practice. Social work research must engage with: the ongoing construction of society and in this way challenge and intervene in dynamic, complex and ever-changing practice, knowledge and contexts.

To sum up it is important to recall Flyvbjerg’s statement that no individual is wise enough to give sufficient answers (Flyvbjerg 2001). The role of both researchers and practitioners is to advance parts of the answer in an ongoing dialogue concerning how eventually to resolve these issues. From this point of view, research and practice both possess part of the solution. Both researchers and practitioners produce limited knowledge. Therefore, importance is attached to challenges from different interests and at different levels. The strength of both practice and research in this view is that they address difficult challenges. The danger for both fields is that they may avoid and reject the challenges. In this way, practice research in social work and social work practice, so to speak, must walk hand in hand without becoming lovers.

References

Bourdieu, P., 1972: Outline of a Theory of Practice, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Bourdieu, P., 1982: The Logic of Practice, Cambridge: Polity Press

Flyvbjerg, B., 1991: Rationalitet og magt, København: Akademisk Forlag

Flyvbjerg, B., 1998: Rationality and Power: Democracy in Practice, Chicago: University of Chicago Press

Flyvbjerg, B., 2001: Making Social Science Matter: Why Social Inquiry Fails and How It Can Succeed Again, New York: Cambridge University Press

Gibbons, J., 2001: Effective practice: social work‘s long history of concerns about outcomes, Australian Social Work, 54(3) , pp. 3–13

Gibbons, M. et al., 1994: The New Production of Knowledge, London: Sage Publications Ltd

Gredig, D. & Sommerfeld, P., 2008: New Proposals for Generating and Exploiting Solution-oriented Knowledge, Research on Social Work Practice 18; 292-300

Ebsen, F. & Uggerhøj, L., 2007: Praksisforskning i socialt arbejde, Unpublished application for funding

Epstein, I., 2001: Using Available Clinical Information in Practice-based Research: Mining for Silver While Dreaming of Gold in Epstein, I. & Blumenfield, S. (eds.) (2001) “Clinical Data-mining in Practice-based Research – Social Work in Hospital Settings”, New York: The Haworth Social Work Practice Press

Epstein, I. & Blumenfield, S. (eds.), 2001: Clinical Data-mining in Practice-based Research—Social Work in Hospital Settings, New York: The Haworth Social Work Practice Press

Harmaakorpi, V. & Mutanen, A. 2008: Knowledge Production in Networked Practice-based Inno-vation Processes – Interrogative Model as a Methodological Approach, Interdisciplinary Journal of Information, Knowledge and Management, vol 3,

Heinrich C. J., 2002: Outcomes-based Performance Management in the Public Sector: Implications for Government Accountability and Effectiveness, Public Administration Review, Vol. 62, No. 6, pp. 712–725,

Hunter, E. & Tsey, K., 2002: Indigenous health and the contribution of sociology: a review, Health Sociology Review 11, 1–2, (http://hsr.e-contentmanagement.com/11.1/11-1p79.htm)

Kjærsdam, W. 2009: Veje til kvalificering af socialt arbejde, Unpublished teaching material

Kristiansson, M. R. 2006: Modus 2 vidensproduktion, DF Revy nr. 2, februar 2006, p. 18-21

Nowotny, H, Scott, P. & Gibbons, M. 2001: Re-thinking Science – Knowledge and the Public in an Age of Uncertainty, Cambridge: Polity Press

Osborne, S. 2002: Public Management – A Critical Perspective, London: Routledge

Pain, H. 2008: Practice Research Literature Review, unpublished draft, Southampton: University of Southampton

Ramian, K. 2009: Evidens på egne præmisser, Vidensbaseret arbejde 2009, 1. februar 2009, vol. 2, p. 1-7

Ramian, K. 2003: Praksisforskning som læringsrum, Uden for Nummer 7/2003 p.4-17

Rasmussen, J., Kruse, S. & Holm, C. 2007:. Viden om dannelse – Uddannelsesforskning, pædagogik og pædagogisk praksis, København: Hans Reitzels Forlag

Reed, J. & Biott, C. 1995: Evaluating and Developing Practitioner Research. Practice Research in Health Care: This Inside Story, London: Chapman Hall

Rehr, H. 2001: ‘Foreword’ in Epstein, I & Blumenfield, S (eds.) (2001) Clinical Data-mining in Practice-based Research – Social Work in Hospital Settings , New York: The Haworth Social Work Practice Press

Salisbury Statement 2009: The Salisbury Statement on practice research,

http://www.socsci.soton.ac.uk/spring/salisbury/, University of Southampton

The Free Dictionary by Farlex http://www.thefreedictionary.com/dialectic

Uggerhøj, L. 2002: Menneskelighed i mødet mellem socialarbejder og klient i Järvinen, Margaretha et al ”Det magtfulde møde mellem system og klient”, Århus: Aarhus Universitetsforlag

Uggerhøj, L. 2000: Den indviklede udvikling, København: Center for Forskning i Socialt Arbejde

Uggerhøj, L. 1995: Hjælp eller afhængighed, Aalborg Universitetsforlag, Aalborg

Winter, S. 1983: Effektivitet og produktivitet i den offentlige sektor 1, Politica, Bind 15, 3

http://www.socsci.aau.dk/foso/eng-index.htm 2006

Author´s Address:

Lars Uggerhøj

Associate Professor

Aalborg University

Department of Sociology, Social Work and Organisation

Kroghstræde 7, 74a

9220, Aalborg Ø

Denmark

Tel: ++45 9940 7293

Email: lug@socsci.aau.dk

urn:nbn:de:0009-11-29269