Situation Analysis of Orphans and Vulnerable Children in Existing Alternative Care Systems in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania.

Mariana Josephat Makuu, Open University of Tanzania

Introduction

The consequences of HIV and AIDS on families has raised an alarming concern for the child care and protection in Tanzania. According to the 2012 national census, Tanzania has a population of about 45 million (United Republic of Tanzania (URT) 2012), and, of these, 44 percent are children below 15 years of age. It is estimated that 3 million Tanzanian children are orphaned due to HIV and AIDS (SOS 2013, PEPFAR 2015) and around 11,216 Ophans and Vulnerable Children (OVC) live in residential care centres (SOS 2013). According to the 2012 national census the city of Dar es Salaam, one of the 30 regions of Tanzania, has a population of 4.5 million with 3 to 5 thousands children living in the streets (UNICEF 2012; Kind Heart Africa 2013). The situation of the OVC is exacerbated by poverty since parents or caretakers from the extended families do not generate adequate income for survival. It is estimated that the Tanzanian population living below the international poverty line spends about $ 1.25 per day, and an estimate of 90 percent of the total population lives below $ 2 per day (Ministry of Foreign Affairs 2013). This implies that many families are poor and the most affected group is the OVC due to a lack of necessary resources to ensure their sustainable well-being.

UNICEF (2016) reported that sub-Saharan Africa has about 45 million orphans and 11.4 million of these children are orphaned due to AIDS). In addition a significant number of these children live with chronically ill or dying parents and/or live in poverty stricken and food insecure households (Formson and Forsythe 2010). These factors have intensified vulnerability of orphans as indicated by (Makuu 2017) stating that Tanzania children are struggling in terms of care, security, and protection. As a result OVC have been pushed into critical discrimination, stigmatisation, exploitation, abuse, and general neglect (Delap 2010, Save the Children 2013).

In Tanzania the increase in number of OVC as a result of HIV and AIDS, poverty, urbanisation, and unemployment has undermined the existing alternative care systems (the extended family/kinship care, statutory foster care, adoption, community based, group homes and supervised child-headed households), in providing adequate care to these children (Makuu 2017). Dar es Salaam, the biggest city in Tanzania has one of the largest numbers of OVC mainly due to HIV and AIDS (TACAIDS 2012). It has a prevalence of 6.9%, compared to the overall national average of 5.1% among the year 15-49 age groups (TACAIDS 2012). A study by SOS (2012) revealed that in Tanzania, 11,565 children were placed in residential care; 80 children were in retention (a detention facility for children who have violated the law which was established under the Law of the Child (Retention Homes) 2009, and 80 in approved schools. The study further noted that 453 children were in prison whereas 578 children were in detention in different cities of Tanzania and Dar es Salaam city is not exceptional.

HIV and AIDS is not the only cause for the children vulnerability in Tanzania. Other factors include living in an abusive environment, living with a sick parent or guardian, living with HIV, living with a disability, living in child-headed households, living in elderly-headed households, living with families facing absolute poverty, and living outside family care. All of these situations can make children vulnerable to abuse and exploitation, illness, withdrawal from school, and emotional distress and trauma (Delap 2010).

Various measures have been instituted by the national and international partners to enhance OVC accessibility to education, health services, nutrition, shelter, and clothing as well as security and protection in Tanzania in general and Dar es Salaam in particular. However, there is increasing concern that the above interventions have not achieved their set objectives, the reasons being that a large number of OVC is still placed in residential/institutional care, and many children are living and spending their lives on the streets (Kind Heart Africa 2013). As such a considerable number of OVC in Tanzania, and particularly in Dar es Salaam, as noted by (Makuu 2017) do not have access to education, health care, and nutrition which indicates insufficient care and protection.

A study conducted by the Ministry of Health and Social Welfare (MoHSW) (2011) on assessment of the situation of children in institutional care in Tanzania indicated that there are more than 500 residential care centres. It is estimated that there are 40 residential care centres providing support to almost 2000 OVC in Dar es Salaam (MoHSW 2011). Unfortunately, in Tanzania apparently no recent nationwide comprehensive situational analysis has been conducted of OVC in various alternative care systems, other than a baseline survey on a situational analysis of OVC in residential care centres conducted by the Department of Social Welfare and non- government organisations. This limits the understanding of the number of OVC under the support of other alternative care systems, the nature of services provided, and challenges experienced. The objective of this paper is therefore, to examine the situation of OVC in existing alternative care systems and explore the treatment of OVC in these systems. Lastly, the paper will recommend what can done to curtail the OVC problem.

1 Background on the Alternative Care Systems

Alternative care refers to the legal placement of a person below the age of 18 years, who is in need of care, to a place of safety, under an individual, family or residential facility, where provision is made for the basic necessities. Alternative care is defined by the (UN 2009) as any formal or informal arrangement, temporary or permanent, for a child who is living away from his or her parents. In Tanzania context, alternative care systems are models of care outside OVC’s biological parents, which provide them with care and support that include kinship/extended family care, adoption, statutory foster care, community-based care, child-headed households, institutional/residential care, and group homes care as the main alternative care systems (Makuu 2017).

1.1 Kinship/extended family

Throughout the history of Tanzania, the extended family is known for its contribution towards the care and support of OVC because most communities believe that a child should be raised by relatives. As indicated in the study by the (UNICEF 2011) on ‘children in informal alternative care’ in Tanzania grandmothers were caring for, almost 50 per cent of orphaned children. However, the ability of the extended family to offer care and support to OVC today has been greatly undermined by increased number of OVC due to HIV and AIDS and thereby creating a burden of care for the older people and children themselves (Abebe & Aase 2007, TACAIDS 2013). In addition, kinship care in Tanzania is facing financial constraints which has make it difficult to support the large number of children in need of care. This is partly because kinship care system is not adequately supported by governments in many developing countries such as Tanzania (Joint Learning Initiative on Children and AIDS (JLCA 2009). Another reason is that in Tanzania there is no specific safety net dealing with the livelihoods of OVC in Tanzania, and the social welfare system which is under performing due to financial, material, and human resource constraints.

1.2 Adoption of a child

Currently adoption of a child in Tanzania is governed by the Law of Child Act 2009 (section 54-76) and the Adoption Rules of Court under the regulation of the Department of Social Welfare. Adoption of a child under the Law of Child Act 2009 recognizes international adoption. However, adoption of child in Tanzania is facing various challenges such as prolonged processes which can discourage foster parents from developing interest in legal adoption (Mkombozi Centre for Street children 2013). In addition, foreigners wishing to adopt a child in Tanzania are required by the law to stay in Tanzania for about 3 consecutive years. This hinders international adoption because many foreigners cannot fulfil condition of the law as they might be employed in their respective countries. Sometimes the foreigners might be working under contract which lasts less than three years which means they cannot qualify for adoption. Apart from implementation of the laws which govern adoption of a child, the literature does not show the impact of adoption policy on promotion of adequate care for OVC in Tanzania and specifically in Dar es Salaam. Tanzanian recognizes and implements inter-country adoption but it is not yet a party to the Convention on Protection of Children and Co-operation in Respect of Inter-Country Adoption. The study by SOS (2014) has indicated that from 2000 to 2012, only 46 Tanzanian children had been adopted by persons in the USA; 14 children had been adopted by non-Tanzanians (countries not specified in the literature); and 62 children had been adopted by the Tanzanians. The total number of adoptions in Tanzania nationally and internationally is only 122 from the year 2000 to 2012, which clearly shows that very few OVC have accessed the family-based care for OVC through adoption.

1.3 Statutory/formal foster care

In Tanzania, statutory/formal foster care refers to the placement of children by a competent authority for the purpose of alternative care in the domestic environment of a family such as friends, neighbours or other people from the community other than the children’s own family that has been selected, qualified, approved and supervised for providing such care (United Republic of Tanzania (URT) 2012). In Tanzania, informal foster care is well recognized and widely used as compared to formal foster care (Mkombozi Centre for Street children 2005) and this mostly happens without legal intervention. It is common to find people who have been raised by relatives even when they had biological parents to care for them. This is mostly due to the cultural practices and beliefs that a child should be raised by his/her own relatives in his/her society. To date there is no specific initiative to ensure that formal foster care is established across Tanzania to address the OVC crisis, although it is indicted in the literature that it is less expensive than institutional care (Williamson & Greenberg 2010, p. 7).

1.4 Community-based care

Community based care can be an effective approach for the sustainable development of OVC due to a variety of community initiated and/or community led interventions (USAID 2010). This type of system includes providing care and support to OVC within their communities and in family-like settings. Effective community based care encompasses five main approaches: community mobilization, community structure, community capacity, resource mobilization, and linkages (USAID 2010). Unfortunately research on community-based initiatives in Africa and specifically in Tanzania is very limited which makes it difficult to evaluate the scope of services related to OVC and related challenges (Abebe & Aase 2007). In Tanzania, the initiatives are based on voluntary, consultative decision making processes, utilization of available resources in the community, and community leadership. Examples of community initiatives may include savings associations and community based organisations that can use volunteers and that receive minimal external support. These may include: labour sharing schemes, agricultural cooperatives, revolving savings and credit associations, burial societies, and mutual assistance groups (Foster 2005b). The positive responses of communities to the provision of care and support to OVC through various initiatives, are often confronted by a number of limitations, which include inadequate appreciation of community initiatives and coping mechanisms by external agencies (Foster 2005a); lack of access to financial and material resources, impact of HIV and AIDS on communities, limited technical capacity (Mathambo & Richter 2007); and a strong reliance upon women volunteers (UNAIDS 2000).

1.5 Institutional/residential care

The orphanages (residential/institutional care centres) in Tanzania are mostly owned by faith-based and non-governmental organisations (MoHSW, 2013). Alternative care in the form of residential/ institutional facilities has been discouraged and is usually considered ‘a last resort’ but the extensive use of residential care in sub-Saharan Africa has been fanned by the death of parents due to AIDS. However, data for OVC in institutional-based care as well as lack of appropriate measures and adequate resources by the government to monitor and evaluate existing systems in Tanzaia are limited and poorly documented (Makuu, 2017). SADC (2010) stated that many residential care facilities in sub-Saharan Africa are unregistered, and Tanzania is not exceptional. This suggest that the numbers of OVC placed in residential care is not known and there is growing evidence that an increasing number of institutional care facilities are being established worldwide (EveryChild 2011a).

1.6 Child-headed households

Emergence of child-headed households has been contributed mostly by lack of the parental care due to death of parents as a result of HIV and AIDS, accidents, non-communicable diseases, and other related causes. Other contributing factors include armed conflicts, family breakdown, and natural disasters (UNICEF 2009a, UNAIDS 2010, Phillip 2011). The findings by Evans (2010) and Kijo-Bisimba (2011) revealed that some children might have decided to remain together in their family home after the death of their parents to prevent the possibility of being separated from their siblings, and to protect the family’s property from being grabbed by relatives. Apart from the fact that child-headed households offer care under the family environment it is regarded as one of the alternative care systems which is vulnerable due to inadequate supervision and protection (Kijo-Simba 2011, SOS 2014 Faith to Action Initiative, 2015). In Tanzania, many children living in child-headed households are not only deprived of their parental care, but also their right to education and health services (MoHSW 2011, SOS 2013). In addition, some child-headed households might be providing care to their very old grandparents, very sick parents or relatives living with disabilities who are unable to fend for themselves (Phillips 2011). Furthermore, children living in child-headed households are confronted with inadequate material and financial resources to fulfil their basic needs, failure to attend school, abuse, stigmatisation, and exploitation (UNAIDS, 2010).

1.7 Group homes

Previous findings recommended for promotion of a small group homes to meet the best interest of children (Save the Children, 2012; Faith Action Initiative, 2014). For example, SOS Children’s Village has been identified as an example of good practice for the residential care of OVC (Abebe 2009, Faith to Action Initiative 2014). This promotes a family-based care copied from western countries and had been established all over the world (Abebe 2009). According to USAID (2010), SOS children’s villages are based on four main principles, namely a caring parent (a mother), family ties (brothers and sisters), a home for each family (house), and SOS villages are part of the community. Tanzania has four SOS group homes which are located in the cities (Dar es Salaam, Arusha, Zanzibar and Mwanza). Unfortunately, only a limited number of the OVC get access because the assessment of children placement in group homes such as SOS is discriminative as it is to a large extent focused on children who are physically and mentally healthy (Abebe 2009).

The limitations facing the existing alternative care systems in Tanzania, indicates that OVC have no access into adequate care. This calls for an efforts by the national and international partners to promote family based care for OVC to ensure that OVC get access to adequate care and support for their wellbeing.

2 Methods and Materials

This article utilizes part of the qualitative data from my dissertation which focused on Family Matters: Strengthening Alternative Care Systems for Orphans and Vulnerable Children in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. The data was collected in Dar es Salaam city from August to December, 2015. The reasons Dar es Salaam was chosen for this study were as follows: It is one of the biggest cities in Tanzania with more than 5 thousands street children in Dar es Salaam city (UNICEF 2012; Kind Heart Africa 2013). It is estimated that, Dar es Salaam consists of more than 40 residential care centres providing care and support to orphans and vulnerable children (OVC) (SOS 2014). It is also estimated that Dar es Salaam has about 2000 OVC which is a big number as compared to other cities in Tanzania (Kind Heart Africa 2013).

To resolve trustworthiness issues in this study, the researcher ensured that she genuinely captured the lived experiences of the participants involved in the qualitative research phase. This was very vital to make sure that the real experiences of the subjects involved in the study were presented and not the researcher’s personal feelings. The audio recording was used during the interviews and focus group discussions to capture as accurately as possible the intended phenomena (Tashakkori & Teddlie, 2003). Furthermore, Gunawan (2015 p.11), note that “to ensure trustworthiness, the role of the triangulation must be emphasized in the context of reducing effect of the researcher’s bias. The researcher observed triangulation by the use of different data collection methods.

2.1 Sampling techniques

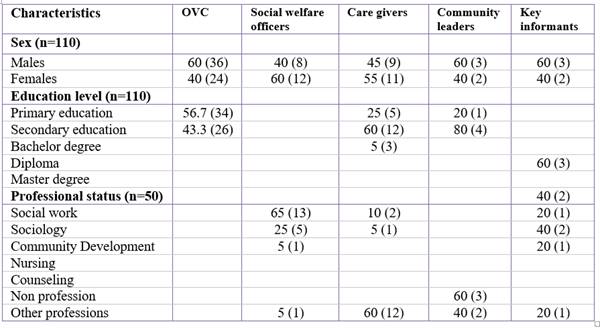

Nonprobability sampling was used in the qualitative phase of this study. Purposive sampling was employed to select the sample for the qualitative phase because the goal was to obtain insights into phenomena, so as to maximize understanding of the underlying phenomena (Onwuegbuzie & Collins, 2007).To select the sample for the OVC, the researcher first selected 6 residential care centres purposively from the 20 care centres which were already selected (through random sampling) for the study. The criteria used for the selection was that those care centres had provided services to OVC for 5 years and above, and were providing care to 30 children and above. 10 OVC were then purposively sampled from every care centre out of the 6 centres to make a total of 60 OVC who were engaged in this study.

The data base for the care centres was used to select purposively 20 caregivers. 20 social workers were purposively sampled from the Department of Social Welfare database. 5 community leaders were purposively sampled from the municipalities’ data bases. 2 key informants were purposively sampled from the Department of Social Welfare databases, 2 from the Ministry of Health, Community Development, Gender, Elderly and Children whereas 1 was purposively sampled from UNICEF. This study involved 110 participants in the qualitative phase. The units of analysis for this study are the existing alternative care systems for OVC and the children (OVC in Dar es Salaam).

Criteria for inclusion

The criteria for inclusion of the participants were based on the following factors:

· Their informed consent.

· Only residential care centres providing care and support to OVC were involved in this study.

· The inclusion of OVC based on those who were placed in institutional/residential care because they were easily accessible. OVC who were selected for this study were male and female children, aged between 10 and 17 years because most of them were in primary and secondary schools. This meant that they possessed some level of understanding of the subject matter and were easier to handle during FGD.

· Caregivers who participated in this study were those working with the residential care centres providing support to OVC in Dar es Salaam.

· Social welfare officers who were involved in this study were those dealing with OVC issues related to alternative care.

· Only directors and administrators dealing with OVC matters directly in residential care centres were involved in the study (i.e. accountants were not part of the study).

· Key informants who were engaged in OVC issues formed part of this study as well as community leaders who had been involved in implementing matters related to OVC.

Criteria for exclusion

· Participants who could not provide informed consent.

· Residential care centres which did not support OVC were excluded from the study.

· Caregivers working in settings other than residential care centres.

· Social welfare officers who were not engaged in issues related to alternative care for OVC.

· OVC aged below 10 and above 17 years and those who were receiving care outside residential care centres.

· Representatives of residential care centres not dealing with OVC and key informants and community leaders who were not directly involved in OVC related matters.

Data Collection Procedures.

Data for the qualitative phase was collected through the use of observation, semi-structured interviews, and focus group discussions. Below is a brief discussion of the tools.

Observations

The researcher in this study employed observation method to compliment other data collection tools. Observation helped the researcher to discover complex interactions in a natural social context (SAGE 2004). It helped the researcher to collect patterns of behaviours and relationships between the OVC and the caregivers; as well as the condition of the immediate environment surrounding them. In this study, the researcher became observer as participant where the researcher identified herself as a researcher and was a member of the group being studied (Kawulich 2005).

Semi-structured Interviews

Semi-structured interview is claimed by Bernard (1988) to be the best choice when it is not possible for the interviewer to get more than one chance to interview somebody. Community leaders and the key informants from the Ministry of Health, Community Development, Gender, Elderly and Children (MoHCDGEC), Department of Social Welfare and UNICEF were interviewed based on the study objectives. The interview guide was prepared by the researcher in English and translated into Swahili language to ease the interview process.

Focus Group Discussions

Focus group discussion (FGD) is a tool which was used to inquire about people’s thoughts, feelings, perceptions and experiences to obtain thorough information about the situation of OVC in existing alternative care systems for OVC in Dar es Salaam (Sherraden 2001). These groups were involved in the study by the researcher because of their depth of knowledge and experiences about the alternative care systems for OVC. In total 10 FGDs were conducted for this purpose; 6 FGDs with OVC, 2 with social workers and 2 with care givers. 10 people were involved in each FGD.

Data Analysis

The data obtained from both interviews and FGDs were transcribed and translated into English. The researcher started preliminary coding of the data manually to decide on what codes to be used as well as naming the categories. Thereafter the data were entered into ATLAS. ti software which provided better management of the data, saved time and offered greater flexibility. This software allowed the researcher to input qualitative data and examine the data for common themes (Teasley & Moore 2010). The software did so by sorting through data, creating conceptual patterns, including larger meanings, and the identification of constitutive characteristics. The researcher reviewed the transcripts several times to examine the interview for key themes and specific topics in order to establish preliminary codes based on the emerging categories. This allowed the researcher to identify codes within the data and arrange them for ease of interpretation.

Researcher’s Position

The researcher appreciated and acknowledged being a part of the society where the participants who were engaged in the study reside. She understood that her own beliefs, experiences, knowledge, and perceptions might interfere with the process of generating knowledge and thus focused on the objectives of the study to enhance the quality of the findings. As a resident in Dar es Salaam city for over 25 years, the researcher is knowledgeable in relation to social, political, cultural, and economic issues and is aware of challenges facing OVC in Dar es Salaam as a result of inadequate permanent care.

The researcher believes that family is a fundamental institution for providing care to OVC but was careful that her bias did not interfere with the findings. Through sharing the idea of promoting the family-based care for OVC in Dar es Salaam, some people became very excited and some promised to take OVC into their families if foster care and adoption processes research process would be improved. This experience could lead to bias in, but the researcher made every effort to prevent it from interfering with the findings.

2.2 Results

Data collected from observations, interviews, and focus group discussions are thematically analyzed based on the established themes and sub-themes that were guided by the objectives of the study as describe below.

|

Theme: Situation of OVC |

Sub-themes |

|

|

Perception on living conditions Fair living conditions Access to basic, social and psychological needs Situation of OVC differ between the care systems Perception on alternative care systems Alternative care systems have played important role Availability of resources determines the quality of care Lack of supervision in child-headed households |

|

Theme: Treatment of OVC |

Sub-themes |

|

|

Views on OVC treatment Abuse, exploitation, discrimination, and stigmatization in care systems. Violation of OVC rights Denied right to health care and education Child engagement in income generating activities OVC intimidation by the care systems |

The Situation of OVC in Existing Alternative Care Systems

The participants reported that the situation of the OVC in kinship settings, residential care, foster care, community-based care, and supervised child-headed households was fair (OVC living standard was at an average level). The meaning attached to this was that at least OVC had access to the important needs for survival like support for basic, social, spiritual, and psychosocial support needs. In addition, the participants revealed that the situation of children placed in group homes was very good (the OVC living standard was at high level) because of adequate human, material, and financial resources. A community leader during an interview session said:

Some children I know who had been raised by members of the extended family have been very successful. Some of these families lived ordinary lives but managed to bring up one to three extra children in their homes. The most important aspect I believe was the unconditional love they offered to these new children. They received good education, which enabled them to access good jobs.

Participants reported that apart from several challenges, the existing alternative care systems had played an important role in supporting OVC. The participants added that the situation of children in various alternative care systems was not similar because some care systems had more resources than others. Moreover, many children placed in various alternative care systems had managed to access support for basic needs as well as social, intellectual, spiritual, and psychological needs. A caregiver said:

To my experience, the situation of children placed in a group home like the SOS is very good with respect to the basic needs, health, and education when compared to some residential care centres. This institution had set aside enough funds to ensure that every child has health insurance, good education, and was able to access support for all basic needs for development. This is different from some residential care centres with limited budgets where children can delay to continue with education.

During FGDs OVC revealed that there were some positive changes in their lives, such as addressing their basic needs and an opportunity to enhance their educational performance from residential care centres. One of the OVC said:

We are able to meet children who had suffered similar problems, get access to education, health services, shelter and food. We get an opportunity to be around people who love and care for us, and who listen to our problems. We feel secure, protected and confident. For example, when I performed poorly in the annual examinations my fellow children in the centre, caregiver and the administrator encouraged me and I was not punished. This built my confidence and I was able to perform well and was selected to join secondary school. Before coming to the centre (after death of my parents) I was living with my uncle who punished me whenever I failed the examinations. This is why he sent me to the centre.

The participants revealed that the situation of some children living in unsupervised child-headed households was poor because of lack of support from an adult person. Participants added that some children were living with very poor families who could not provide for their basic needs. Participants stated that some of the children are cared for by old grandparents who could not protect them from violence, stigmatisation, and discrimination. A key informant had this to say:

Many children without parental care especially in the villages are left under the care of very old grandparents and sometimes alone under unsupervised child-headed households. It turns out that children are the ones to care for their grandparents and young siblings, which means that they cannot go to school. These children have to look for firewood for energy at home and sometimes have to work on farms to earn some money for food. These children are living under very poor conditions because of lack of addressing of basic needs.

OVC Treatment in Various Alternative Care Systems

The researcher probed the views and perceptions of respondents regarding OVC treatment in the existing alternative care systems. Participants reported that some children received good treatment, but a considerable number of children were ill-treated. For example, a care giver said that some residential care centres were exploiting the children by engaging them in income generating activities which did not benefit the children. She shared the following experience:

One Saturday I attended a wedding ceremony at one of the social halls in the city centre. Celebrations started around 9.00 pm. An announcement was made inviting a special children’s group of 12 singers. These were 6 boys and 6 girls who seemed to be between 10 and 15 years of age. Before starting the song one of the children introduced the group that they were from one orphan centre in the city. It was announced by the master of the ceremony that those children were already booked to another wedding for the week that followed.The question that still lingers in my mind to date is: why did the residential care centre engage those children in this activity? How did the children manage to participate in weddings almost every Saturday as primary students? How about their schoolwork?

The researcher further probed to find out whether there were notable differences between care by extended families and adoption. This related to participants’ response that the treatment of OVC in various alternative care systems varied. One caregiver said:

Adoptive parents can be more committed to care for OVC because they have taken the child willingly; child laws and regulations also bind adoptive parents. Social welfare officers will monitor the care of the child to ensure that his/her rights are not violated. Some relatives will opt to take care of the children left behind in order to benefit from the wealth left behind by OVC parents.

During interviews and FGDs, participants also said that children might be abused and denied rights to education by relatives even if their parents left property behind such as houses, vehicles, and farms. Children might not disclose the information due to intimidation from the members of the extended family. A community leader said:

My experience shows that some children have ended up living at the orphanage centres after mistreatment from relatives. It might also happen that some relatives decide to send OVC to the care centres because they fail to support them due to poverty. However, some members of the extended family might be enjoying the wealth left behind by their deceased brothers/sisters, while placing children left behind in care centres. This might happen especially when children are too small to understand what was left behind by their parents.

Participants also said that children might be abused and denied rights to education by relatives even if their parents left property behind such as houses, vehicles, and farms. Children might not disclose the information due to intimidation from the members of the extended family. One of the OVC stated:

After my parents’ death, I went to live with my aunt and my brother was taken by my uncle. My brother had no problem living with our uncle and he was able to continue with the advanced secondary education. On my side, I was supposed to join a public secondary school but my aunt did to help with all house chores when she went to work. One of my aunt’s friends helped me to escape from my aunt’s house and brought me to the social welfare office. I was able to access secondary education after I was placed in a care centre although I was already delayed for two years.

Through observation, the researcher noted that many children in all care centres visited looked happy and were interacting with one another, which might explain the fact that they received good treatment. However, four children from different care centres visited looked unhappy and were not interacting with others because they were sick and were being treated for malaria.

Sometimes a difference can be noticed between orphans taken care of by relatives and those taken care of by adoptive parents. Adoptive parents can be more committed to care for OVC because they have taken the child willingly; child laws and regulations also bind adoptive parents. Social welfare officers will monitor the care of the child to ensure that his/her rights are not violated. Relatives from the extended family might agree to take care of the children but sometimes do not possess enough resources for development of the child. Some relatives will opt to take care of the children left behind in order to benefit from the wealth left behind by OVC parents. Some relatives have mistreated OVC by making them stay home (and not go to school) and perform house chores as if they were house girls/houseboys.

Another caregiver shared a similar perspective testifying that he witnessed the suffering of a four year old girl child who was physically abused by her stepmother. This is what he had to say:

This child was placed in my institution by the social welfare department. She sustained serious burns after her step-mother poured very hot water on her back intentionally. This woman was placed in prison for five years and the father of the child could not be found even with a search warrant from the police.

During interviews and FGDs, participants also said that children might be abused and denied rights to education by relatives even if their parents left property behind such as houses, vehicles, and farms. Children might not disclose the information due to intimidation from the members of the extended family. A community leader said:

My experience shows that some children have ended up living at the orphanage centres after mistreatment from relatives. It might also happen that some relatives decide to send OVC to the care centres because they fail to support them due to poverty. However, some members of the extended family might be enjoying the wealth left behind by their deceased brothers/sisters, while placing children left behind in care centres. This might happen especially when children are too small to understand what was left behind by their parents.

One of the OVC stated:

After my parents’ death, I went to live with my aunt and my brother was taken by my uncle. My brother had no problem living with our uncle and he was able to continue with the advanced secondary education. On my side, I was supposed to join a public secondary school but my aunt required me to help with all house chores when she went to work. One of my aunt’s friends helped me to escape from my aunt’s house and brought me to the social welfare office. I was able to access secondary education after I was placed in a care centre although I was already delayed for two years.

Through observation, the researcher noted that many children in all care centres visited looked happy and were interacting with one another, which might explain the fact that they received good treatment. However, four children from different care centres visited looked unhappy and were not interacting with others because they were sick and were being treated for malaria.

2.3 Discussion

Several limitations must be kept in mind when interpreting results of this study. The first limitation is lack of information on situational analysis of OVC in existing alternative care systems; that would help the researcher understand the magnitude of OVC care need. The second limitation is the fact that this study involved only children placed in residential care centres which makes it difficult to understand the ideas of OVC from other settings. The third limitation is that because the data are collected from interviews with the key informants and community leaders; and FGDs with the OVC, social workers and care givers, it cannot represent the whole study population but only a specific studied area (the findings of the study reflect only the perceptions of the respondents not validated by quantitative data).

However, the study has come up with relevant findings in examining the situation of OVC and treatment of OVC in various alternative care systems. The study recommends for some measures to address challenges facing OVC in relation to inadequate care and protectoion. In addition most of researches on OVC focus on assessment of basic needs especially in residential care but this study fills the gap in research by examining the overall situation of OVC in existing alternative care systems.

An emerging issue in the findings is that the situation of OVC in various alternative care systems was largely dependent on resource availability. The findings revealed that the situation of OVC was regarded as fair in kinship, residential, foster, and community-based care as well as in supervised child-headed households. The main reason which was apparently that OVC in various alternative care systems had access to the fulfilment of basic and social needs. The participants further believed that the situation of OVC in adoptive and group homes tended to be very good due to adequate human, financial and material resources. The data from this study corroborate findings by Faith Action Initiative (2015) which indicated that many children in kinship care had access to basic necessities and education and they were not exposed to many behavioral problems such as robbery and drug abuse. However, according to the findings of this study, some OVC live with poor families and sometimes very old grandparents who have no regular income support from government institutions and NGOs. This finding is in line with previous studies (Williamson & Greenberg 2010, Roelen & Delap 2012) which indicated that a considerable number of extended families providing support to OVC languished in poverty. This means that children in these families suffer from inadequate food, shelter, clothing, medical care and education.

The findings from the previous studies acknowledge the fact that residential care centres constitute the best option for children with unique conditions such as those living with disability who might be in need of special care (Abebe 2009, USAID 2010). In addition, residential care centres provide short-term placement for siblings which helps children to grieve together for the loss of their parents. However, the findings by USAID (2010) revealed that large residential care centres lacked suitable therapeutic treatment for children and also expose children to abuse and exploitation. Findings by USAID (2010) and SADC (2010) indicate that children in statutory foster care and adoption programmes have benefited from proper care and remained connected to their culture. Children in group homes are attached to mothers who have been trained in parenting skills and through socialization children grow up like brothers and sisters (Abebe 2009, USAID 2010).

The findings of this study indicated that unsupervised child-headed households are fast proliferating but children are living in very poor conditions because of lack of supervision and resources to meet their basic needs. This is in line with the findings of Kijo-Bisimba (2011) on protection of orphaned child-headed households in Tanzania which revealed that unsupervised households of this nature are invisible, especially in places where media coverage is limited. This has caused suffering to the children due to lack of support from relatives, NGOs, and government institutions. Findings by SADC (2010) and Phillips (2011) indicate that child-headed households had emerged as a response to inefficient alternative care systems for OVC. These findings includded the suggestion that many children in child-headed households live in extreme poverty and under dangerous conditions but there were no statistics of such households.

The findings of the present study are crucial for social welfare officers and national and international partners to understand that the wellbeing of OVC in alternative care systems is determined by the availability of resources. The study empirically demonstrated that children under the care of poor families, aging grandparents, and unsupervised child-headed households exist under poor conditions. For example they do not receive adequate food, education, and medical care,and they are exposed to abuse, violence, and exploitation. The implication is that those children might suffer from mulnutrition and disease as well as illeteracy which would create a cycle of poverty in their future lives.These findings call for stakeholders to ensure that more research is conducted to assess the situation of OVC in various alternative care systems in order to establish effective programmes that would ensure that basic and social needs of OVC are met.

FGDs and interview findings indicated that the treatment of OVC in kinship, residential and foster care and adoption, community-based care, supervised child-headed households, and group homes tended to be generally poor. It was also found that adoptive parents might be more committed to care for OVC because they adopted children willingly and adoption is a legally controlled process. Participants noted that the wealth left behind by deceased relatives could convince some members of the extended family to take care of the OVC. However some such people had mistreated OVC and denied them the right to education according to the findings. This finding is in line with the studies, by UNICEF (2010), Biehal, Cusworth, Wade, & Clarke (2014), and the Faith to Action Initiative (2014), which indicated that children in various alternative care systems faced abuse, violence, and exploitation. For example, some community members used OVC who were under their care as household servants (EveryChild 2011a). Furthermore, children receiving support from non-kins (and even some kins households) were treated as child servants even if the initial purpose was to send them to school.

The findings of the present study are crucial for OVC stakeholders to understand the intricacies in relation to OVC treatment in various alternative to establish an effective mechanism for the security and protection of OVC in various alternative care systems. Available literature reveals that children should grow in a family environment which provides permanent care (UN 2009, Save the Children 2013). This is supported by attachment theory which notes that, for the child to grow successfully, she/he will require a positive and continuous relationship with the caregiver (Bowlby 1951, p. 13) such as a mother or permanent mother substitute. Again, relevant procedures should be utilised in searching for alternative families for OVC. Failure to recruit effective families could result in abuse, discrimination, stigmatisation, violence, and exploitation of children. This study’s findings calls for stakeholders to employ the ecological approach to child protection which seeks to understand the interaction between children, families, communities, and society and their impact on the wellbeing of the child (Wright 2004). The findings of this study suggest that social welfare officers should implement the ecological systems theory during OVC placement in alternative care systems, through understanding that a new environment would always require effective strategies to enable children to cope successfully (Kassim 1992).

2.4 Conclusion

The paper examined the situation and treatment of OVC in various alternative care systems. The chapter concludes that, there should be sustainable programmes to ensure that OVC basic needs are met in accordance with their developmental progression. From the findings, it may be suggested that national and international partners should consider establishing an effective mechanism to support families and communities in managing the situation of children deprived of parental care. The treatment of OVC in various alternative care systems was reported by the participants to be poor. Examples of poor treatment being apparently daily reports related to abuse, violence, discrimination, and exploitation of children. This implies that an effective framework for security and protection of children should be established to protect their rights. The national and internation partners should ensure that OVC needs related to care, security and protection are highly secured for the development of the children.

2.5 Recommendations

It is recommended that the national and international partners, should adopt a holistic approach to addressing alternative care for OVC in order to ensure adequate care, love, and protection of every child. Attention should be directed at children without parental care as well as children living with chronically ill parents, poor families and communities.

The Government of Tanzania has to support promotion of social welfare services to ensure that OVC have access to basic needs, education, and health care services. Most importantly, the Government of Tanzania, through the MoHCDGEC, has to consider inadequate alternative care for OVC a developmental indicator. Accepting this would require the design policies and programmes which focus on targeting children without parental care, poor families, and communities.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author declares no potential conflict of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author received no financial support for the research and/or authorhship of thus article.

References

Abebe, T., & Aase, A. (2007). ‘Children, AIDS and the politics of orphan care in Ethiopia: The extended family revisited’, Social Science and Medicine 5, 1058-2069.

Abebe, T. (2009). Orphan hood, poverty and the care dilemma: Review of global policy trend. Norwegian Centre for Child Research, Trondheim, Norway.

Bernard, H. R. (1988). Research methods in cultural anthropology. Newbury Park, California: SAGE.

Biehal, N., Cusworth, L., Wade, J., & Clarke, S. (2014). Keeping children safe: allegations concerning the abuse or neglect of children in care. University of York.

Bowlby, J. (1951). Maternal care and mental health. World Health Organisation Monograph (Serial No. 2).

Delap, E. (2010). Protect for the future. Placing children’s care and protection at the heart of the MDGs. EveryChild, ChildHope, Railway Children, Consortium for Streets Children, ICT, Retrak, Save the Children, the International HIV and AIDS Alliance and War Child, London.

Evans, R. (2010). The Experiences and priorities of young people who care for their siblings in Tanzania and Uganda, Research Report, Reading, UK: School of Human and Environmental Sciences, University of Reading. Retrived from http://www.reading.ac.uk/ges/Aboutus/Staff/r-evans.aspx) on Sept. 29/2018.

EveryChild. (2011a). Scaling down: Reducing, reshaping and improving residential care. EveryChild, London.

Faith to Action Initiative. (2015). The continuum of care for orphans and vulnerable children. Oak Foundation. Oak Foundation.

Faith to Action Initiative. (2014). Children, orphanages and families: a summary of research to help guide faith-based action. Oak Foundation.

Formson CB & Forsythe S. (2010). A costing analysis of selected orphan and Vulnerable Children (OVC) programs in Botswana. Health Policy Initiative, Task Order 1. Futures Group, Washington.

Foster, G. (2005a). “Under the radar – Community safety nets for children affected by HIV/AIDS in poor households in sub- Saharan Africa”, UNRISD, Geneva.

Foster, G. (2005b). “Bottlenecks and drip feeds: Channelling resources to communities responding to orphans and vulnerable children in southern Africa”. Save the Children: London.

Gunawan, J. (2015). Ensuring trustworthiness in qualitative research. Belitung Nursing Journal 2015; 1:10-11.

Joint Learning Initiative on Children and AIDS (JLICA). (2009). Home truths: Facing the facts on children, AIDS, and Poverty. Retrived from http://www.jlica.org on Dec. 30/2018.

Kasiram, M.I. (1992). School social work service delivery: models for future practice, submitted in part fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, Durban: Faculty of Arts, University of Durban-Westville.

Kawulich, B. B. (2005). Participant observation as a data collection method. Forum Qualitative Social Research 6 (2).

Kijo-Bisimba, H. (2011). Vulnerable within the vulnerable: protection of orphaned child heading households in Tanzania. A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirement for the Degree of Philosophy in Law-University of Warwick, UK.

Kind Heart Africa. (2013). Tanzania orphanage project.

Makuu, M.J. (2017). Family Matters: Strengthening Alternative Care Systems for Orphans and Vulnerable Children in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. A dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEGREE IN SOCIAL WORK (University of Botswana).

Mathambo, V., & Richter, L. (2007). ‘We are volunteering’: Endogenous community- based responses to the needs of children made vulnerable by HIV/AIDs”, Human Sciences Research Council.

Mkombozi Centre for Street children. (2013). Overview of the current adoption situation in Tanzania.

Mkombozi Centre for Street children. (2005). Literature review of foster care. Tanzania.

Ministry of Foreign Affairs. (2013). Country profile paper. Danish Embassy in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania and Department for Africa.

Ministry of Health and Social Welfare. (MoHSW)-Department of Social Welfare. (2013). The most vulnerable children in Tanzania. Tanzania.

Ministry of Health and Social Welfare. (MoHSW)-Department of Social Welfare. (2011). Assessment of the situation of children in residential care in Tanzania. Tanzania.

Onwuegbuzie, A. J., & Collins, K. M. T. (2007). A typology of mixed methods sampling designs in social science research. The Qualitative Report. ANOVA Southeastern University.12 (2), 281-316.

PEPFAR (US President Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief). (2015). Tanzania country operational plan: Strategic directional summary. Tanzania.

Phillip, C. (2011). Child-headed households: a feasible way forward, or an infringement of children’s right to alternative care? Netherlands.

Roelen, K., & Delap, E. (2012). Researching the links between social protection and children’s care in Sub-Saharan Africa-A Concept Note.Centre for Protection, Institute of Development Studies and Family for Every Child.

SADC. (2010). Development of SADC minimum package of services for orphans and vulnerable children and youth: The situation of orphans and other vulnerable children and youth in SADC Region. Regional Situation Analysis Report. Gaborone, Botswana.

SAGE. (2004).The SAGE encyclopaedia of social science research methods. SAGE Publications

Save the Children. (2013). Save the children’s child protection strategy 2013-2015. Kingdom: Save the Children.

Save the Children. (2012). Guidelines for the alternative care of children. Policy Brief, November, 2012. United Kingdom: Save the Children.

Sherraden, M. (2001). Service and the human enterprise (Perspective). St. Louis: Washington University, Center for Social Development.

SOS, Tanzania. (2013). Child rights based situational analysis of children without parental care and at risk of losing parental care. Tanzania.

SOS, Tanzania. (2014). Assessment report of the alternative care systems for children in Tanzania. Published in Austria by SOC Children’s Villages International.SOS, Tanzania. (2012). Child rights based situational analysis of children without parental care and at risk of losing parental care.

TACAIDS. (2012). Country progress reporting. Tanzania Mainland.

TACAIDS. (2013). National HIV and AIDS response report 2012. Tanzania Mainland.

Tashakkori, A. & Teddlie, C. (2003). Handbook of mixed methods in social and behavioural research. Thousand, Oaks, C.A: SAGE.

Teasley, M.L. & Moore, J.A. (2010), A mixed methods study of disaster case managers on issues related to diversity in practice with Hurricane Katrina Victims. Florida State University.

UN. (2009). Guidelines for the alternative care of children. Human Rights Council, 11th Session, United Nations, Geneva.

UNAIDS. (2010). Global report. New York: Joint UN Programme on HIV-AIDS.Geneva.

UNAIDS. (2000). Caring for carers: Managing the stress in those who care for people with HIV and AIDS. Geneva: UNAIDS Best Practice Collection. Geneva.

UNICEF. (2016). Monitoring the situation of children and women. Retrieved from: http://www.dataunicef.org on 15/12/2018

UNICEF. (2012). UNICEF annual report, United Republic of Tanzania.

UNICEF. (2011). Children in informal care- discussion paper. UNICEF child protection section-New York.

UNICEF. (2010). At home or in a home? Formal care and adoption of children in Eastern Europe and Central Asia. Geneva. UNICEF Regional Office for CEE/CIS.

UNICEF. (2009a). Africa’s orphaned and vulnerable generations. Children affected by AIDS. UNICEF, New York.

United Republic of Tanzania. (URT). (2012). Tanzania National Bureau of Statistics; National population census. Tanzania.

USAID. (2010). The scale, scope and impact of alternative care for OVC in developing countries: A review of literature. Centre for Global Health and Development Boston University. USA.

Williamson, J. & Greenberg, A. (2010). Families, not orphanages. Better Care Network, New York.

Wright, S. (2004). Child protection in the community: A community development approach. Child Abuse Review, 13, 384–398.

Author´s

Address:

Mariana J. Makuu

Faculty of Social Sciences (FASS)

Department of Sociology and Social Work

The Open University of Tanzania

P.O.Box 23409

Dar es Salaam, Tanzania

Office Tel Direct: +255 22 2668992

Fax: +255(0)22 2668759

m_josephat@yahoo.com

Appendix 1:

Table 1: Demographic Characteristics of Participants.