Culture and the new geography of social exclusion: The New York experience

Mark J.

Stern, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia

Susan C. Seifert, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia

1 Introduction

The welfare state has been under siege for the past generation. It’s been accused of undermining the fiscal integrity of the state and encouraging moral hazard. Yet, the most galling neoliberal attack on the welfare state had its origins in New Left critiques of the 1960s: that a hierarchical, bureaucratically-organized set of programs undermines individual self-determination and constitutes a threat to human freedom. The New Left critique, itself, rested on the earlier success of the welfare state in reducing the extent of material deprivation within the population and in uncovering a new set of less-tangible social needs and wants. Thus, at this historical moment, those on the Left face a two-front war, as it were. At the same time that we recognize the failure of government to address increasing material deprivation, we must also acknowledge the challenge of those new needs and wants and how welfare services can simultaneously respond to increasing social exclusion and the broader skepticism of the public.

This paper views the welfare state dilemma through the lens of culture as a social right. Indeed, the 1948 UN Universal Declaration of Human Rights and 2001 UNESCO Universal Declaration on Cultural Diversity recognize the right to culture as a human right. Our paper begins with a detailed study of social wellbeing in New York City to examine the new geography of social exclusion in American cities and its connection to changing social and cultural conditions. It then uses the capability approach to suggest how cultural services have become more central to social welfare provision, both because of their role in responding to the new needs and wants mentioned above and by mitigating the effects of neoliberal social neglect in health, education, and personal security. Finally, it looks ahead to how the cultural sector has addressed issues of diversity, equity, and inclusion and suggests how capability-promoting policies provide an alternative to the current approach (UN 1948; UNESCO 2002).

Before proceeding, we want to make a couple of stipulations about the “welfare service state” in an American context. Most obviously, unlike much of Europe, the US has not enjoyed the upsurge in individualized services focused on the personal challenges of low-income residents. Indeed, the expansion of social services in the US coincided with the expansion of Social Security during the early 1970s. Furthermore, in the US, personal social services were some of the first programs to face cuts when Congress established Title XX a few years later as a way to limit open-ended federal funding of services.

Second, periods in which the federal government has taken the lead in policy innovations are relatively rare in the US. If we are looking for new approaches to welfare today, we are more likely to find them in local government and grassroots organizations than in national policy. Indeed, we will argue that New York City’s recent efforts to see culture and the arts as a form of social engagement that promotes social wellbeing is an instructive example of how capability-promoting approaches can influence future social welfare policy.

2 A new welfare state?

The 1970s represented the high point of welfare states worldwide, as many nations succeeded in providing a social wage to populations that had historically been excluded from full participation in the labor market. In a semi-welfare state like the US, the unemployed, older residents, and people with disabilities won economic rights during the 1970s that would have been unimaginable two decades earlier. Even single mothers collecting social assistance (Aid to Families with Dependent Children)–the population group that had been most stigmatized historically–for a brief period were entitled to welfare payments that were higher than many of them could expect from paid employment.

Yet, just as the old welfare state was reaching its height during the 1970s, it encountered two sources of headwind. The rise of neoliberalism represented the mobilization of business and social elites to reinforce class power and link social discipline to labor market dependency and neo-conservative moralism. As David Harvey notes, neoliberalism was able to appropriate elements of the New Left critique of liberalism that emphasized the government’s threat to personal freedom and liberty (Harvey 2005).

Three decades later, neoliberalism emerged from the financial crisis of 2007-10 as a spent ideological force. Although the so-called “populist” form of anti-neoliberalism is often more frightening, neoliberalism’s hegemony will not be the major challenge to the welfare state moving forward.

The real challenge to the future of the welfare state derives from the success of the old welfare state. By eliminating the threat of poverty for a majority of the population, the welfare state has generated new needs and expectations as well as new discontents. Neoliberalism has left behind a legacy of increased inequality and social exclusion. But as neoliberalism fades, the expanded demands of people to live a life they have reason to value—a central focus of the capability approach—is likely take center stage.

3 From social exclusion to social wellbeing

Social exclusion is a complicated concept, one that has been made less legible by some policymakers’ frequently manipulative use of the idea. Although the concept grew out of Catholic social thought and republican interest in social solidarity, in the English-speaking world—for example, the New Labour administration of Tony Blair in Britain—exclusion has often been deployed to sugarcoat workfare and other programs focused on “activating” economically marginalized groups (Daly and Silver 2008).

Indeed, applying social exclusion to economic status presents a host of problems. By focusing on those excluded from the labor force, the concept implies that getting a job means one’s economic problems are over. At the very least, this ignores the problems of the working poor, for whom a job is no guarantee of an adequate income. In a more extreme interpretation, some would suggest that the exploitation of workers both inside and outside of the formal labor market is a general phenomenon.

Given these issues, this paper steers away from using social exclusion to discuss purely economic relations. Rather, we use the concept to talk about two other aspects of social wellbeing, which we shall term institutional and relational social exclusion. We use institutional social exclusion to refer to how one’s position in the economy carries over to other aspects of wellbeing. Specifically, does a neighborhood’s average economic status influence the health, educational opportunities, or personal security of its residents? In a just society, a community’s social rights to health, education, and security would not be a function of its economic status. From another perspective, if there is a carryover—if living in a low-income community means one is less likely to have good health, education, or personal security—this represents institutional social exclusion.

Second, we use relational social exclusion to refer to the extent to which one lacks social connections or a robust social network. This aspect of social life has often been characterized as social capital. Having the opportunity to build a full social life is itself a desirable state, whether or not one chooses to take advantage of those opportunities. Furthermore, under certain conditions, having social connections can mitigate the effects of institutional social exclusion.

The idea of social exclusion often carries an explicit or implied duality; one is either excluded or not. It often carries as well a clear normative undercurrent; it is better to be included than excluded. We will argue, however, that at least as a starting point, it is more productive to identify a set of critical dimensions of advantage and disadvantage and then place individuals and groups along the advantaged/disadvantaged continuum. Thus, we will talk about degrees of exclusion.

Below we apply the core elements of the capabilities approach—in particular, its idea that freedom is a state within which one has the opportunity to lead a life one has reason to value—to urban communities. In melding the idea of social exclusion with capabilities, we will elaborate a concept of social wellbeing. To the extent one’s living conditions afford greater advantage with respect to the different dimensions of social wellbeing, a community reduces its level of social exclusion and thereby enhances opportunities for residents to pursue their notion of the good life.

4 Changing social context of welfare services—the new geography of exclusion

The expression of new needs and wants has been complemented by significant changes in American social structure. The centuries-old structuration of American society by race, gender, and class has undergone a fundamental shift. In particular, the economic emergence of black women during the 1980s and 1990s (a shift largely ignored by social policy) has altered the caste-like stratification of the previous century. Today, African American inequality is a product of a set of hurdles and screens—many of which are “race neutral” on the face of it—that sort most low-income African Americans into poor jobs and neighborhoods but provide many individual African Americans and members of other ethnic minorities with opportunities for social and geographic mobility that were blocked several generations ago. Indeed, the Black Lives Matter movement has drawn much of its support from the realization that even those African Americans who have “made it” can experience status declines when faced with an aggressive cop or frightened Starbucks manager (Dias, Eligon, and Oppel 2018). At the same time, the nature of immigrant flows from Asia and Latin America, higher rates of racial intermarriage, and the increasing number of residents who identify as multi-racial have punctured a binary race template. As a result, the profound racial residential segregation that defined American cities for much of the 20th century has been replaced during the past generation with an increasing economic segregation (Katz and Stern 2006).

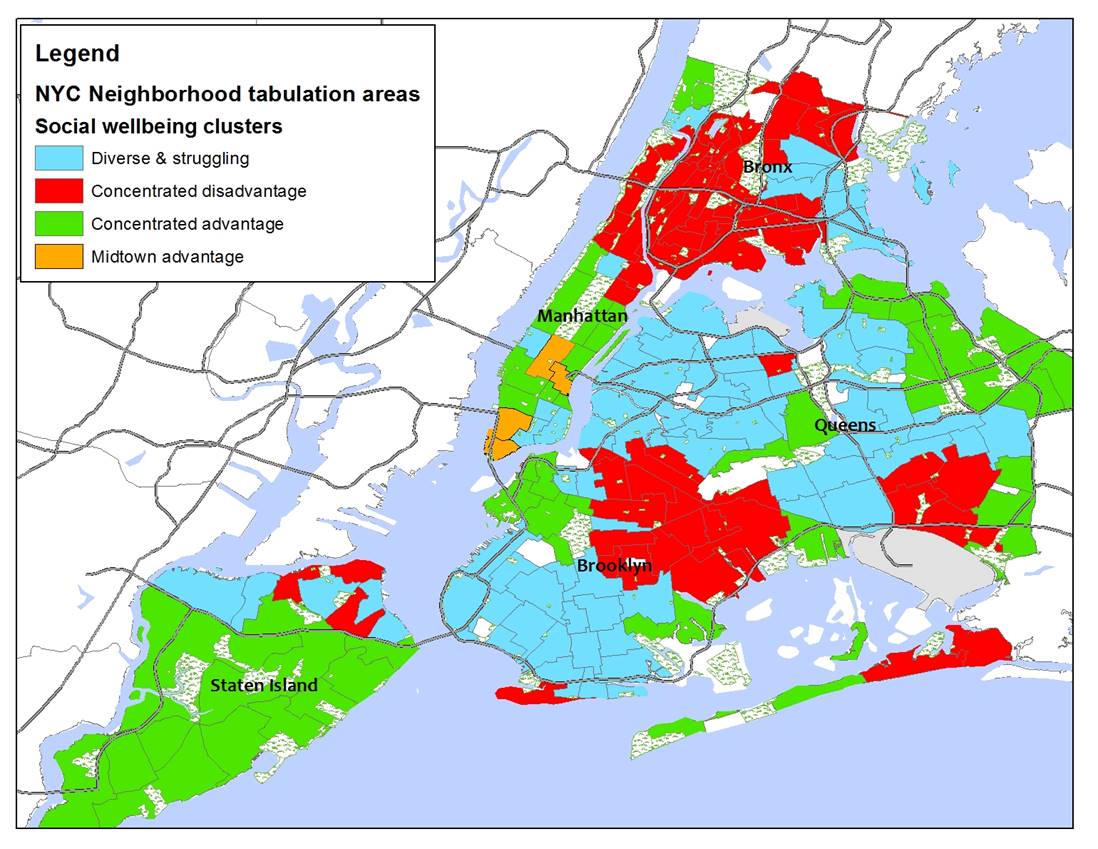

The shift from racial to economic segregation is part of the new geography of exclusion that now characterizes American cities. We have investigated this new urban geography empirically in our study of New York City. With indicators derived from the capability approach, we developed a multi-dimensional measure of social wellbeing for approximately 200 neighborhood areas. Specifically, we used 2013-15 data on ten dimensions—economic wellbeing, housing burden, ethnic and economic diversity, health access, personal health, school effectiveness, personal security, environmental amenities, social connections, and cultural assets—to estimate levels of social wellbeing and exclusion across the city (Stern and Seifert 2013/2017).

The resulting analysis and map show sections of New York City that have concentrated social disadvantage across virtually all dimensions of our measure and an even larger number of diverse and struggling neighborhoods that are disadvantaged on some dimensions but less disadvantaged on others.

Figure 1. Social wellbeing status of New York City’s neighborhood tabulation areas, 2016-17. Source: Stern and Seifert (2017).

Since the 1970s, the US has also witnessed an increasing individualization and depatterning of the life-course. This shift has been most profound in the transition from childhood to adulthood. In the middle of the 20th century, this transition was a sprint. The majority of the population left school, found a job, left their parents’ home, married, and became parents within a few years. By the end of the century, this sprint had become a ramble, with a critical set of life events stretching out over a decade or more and a many events (including marriage and parenting) as far from universal. The changing transition to adulthood is important in its own right and as an indicator of the increasing desire of residents and citizens to individualize their choice of functionings within the range of capabilities open to them (Katz and Stern 2006).

Individual choice was not the only social force influencing the extended transition to adulthood. The financial crisis of 2007-10 and the associated spike in youth unemployment reinforced this trend. For example, between 2000 and 2016, across the US, the proportion of young adults (20-34 years of age) living with a parent increased from 18 to 29 percent.

Our analysis in urban communities of social wellbeing across multiple dimensions led us to two conclusions. First, the extent to which economic inequality influences other dimensions of social exclusion remains quite profound. In New York City and Philadelphia, the economic standing of the neighborhood in which you live influences to a large degree your health, the quality of your children’s education, and the likelihood that you will be a crime victim. Second, although cultural opportunities also tend to be a function of economic standing, when we control for these factors, cultural opportunities exert a mitigating influence on other dimensions of wellbeing.

5 Cultural marketization and its discontents

As the demands and expectations of residents and citizens have changed, the role of culture in the constellation of social wellbeing has also altered. In the 20th century welfare state, culture played a relatively minor role: to provide a means of “bringing culture” to populations that were assumed to have none. This approach, developed at the local level in the settlement house movement of the early 20th century, was eventually incorporated nationally, first into the New Deal cultural program of the 1930s and then amplified during the Great Society programs of the 1960s, which led to the creation of the national endowments for the arts and humanities and the Institute for Museum and Library Services. These efforts promoted an “American” culture that could be the rallying point for national unity and, during the Cold War, the projection of American culture and power across the world.

As was the case internationally, this vision of a unified American culture tied to a broader “Great Society” social welfare program began to disintegrate during the 1970s just as it was realizing its century-long objectives. In its place, culture shifted from a focus on a unified American culture to recognition of the diversity of American cultures. The tension between culture as a common lens through which to make sense of the world and cultures as class- or ethnic-specific perspectives that emphasize the differences between groups, classes, and races has posed a dilemma that is yet to be resolved.

The emergence of what the symposium organizers have called the welfare service state calls for a reset of the role of culture within the array of social services. As we have noted, within the old welfare state, culture played a minor role, which translated into a relatively small fiscal commitment on the part of the federal government. Even that role was limited, with a large share of the federal funding directed to state cultural councils.

In some ways, this lack of a strong governmental role in cultural funding has been an advantage. Unlike many other Western democracies, the US does not have a massive bureaucratized cultural sector that relies on government funding. The increased emphasis on quality of services has often run up against unresponsive public bureaucracies, like the public education system in the US. In contrast, the US equivalent of a cultural ministry is so limited that Congress regularly threatens to eliminate it altogether.

Instead, the cultural sector has expanded primarily as a result of commercial and philanthropic investments, which carry their own challenges. Culture in the US has grown progressively more unequal over the past generation. Led by philanthropy, nonprofit cultural organizations during the late 20th century experienced “policies of institutionalization” which, in the words of Paul DiMaggio, focused on “encouraging small organizations to become larger and large organizations to seek immortality” (DiMaggio 1991). Then, like other nonprofits, cultural organizations experienced marketization—the demand that they act like for-profit entities, which benefited larger organizations with more resources over smaller ones. As a result, small- and middle-sized cultural organizations have faced an increasingly precarious existence, especially if they serve low- and moderate-income consumers.

The increasing inequality of cultural services could be seen as a minor problem given the marginal role that the arts and culture played in the previous welfare state era. However, as people have come to demand services that support their diverse identities and increasingly individualized ways of life, the inequality of cultural access and opportunities has become more significant.

We can gain a preliminary understanding of the change in culture’s role in welfare by employing the lens of the capability approach. Using Martha Nussbaum’s formulation, we can identify “central capabilities”—including senses, imagination, thought, emotions, play, and affiliation—for which culture and creativity play a critical role in enabling people “to pursue a dignified and minimally flourishing life” (Nussbaum 2011).

Because economic wellbeing is the foundation of other capabilities, it is notable that the cultural sector represents an increasing proportion of the labor force. Among employed paid workers in US metropolitan areas between 1950 and 2010, for example, artists’ occupations increased from 343 thousand to 1.19 million, an increase of 245 percent at a time when the employed labor force increased by only 117 percent. Thus employed artists represented an increase from 1.1 to 1.8 percent of the labor force.

Beyond economic wellbeing, the capabilities approach points to a wider set of ways in which engagement in the arts and culture, by professionals and the general public, are central to achieving a life one has reason to value. Our interviews in New York City with cultural agents based in two neighborhoods—Fort Greene (Brooklyn) and East Harlem (Manhattan)—suggest that they view their work as a form of community and civic engagement. They identified three ways their work enhances community wellbeing—by generating social connections, by providing political and cultural voice to groups that are often marginalized, and by animating public space and concern about the public environment. A musician who with his daughter leads a small music and dance program in East Harlem (and who is famous for his food metaphors) provides a poignant perspective on the importance of culture to communities. He describes culture as the cumin in a stew, the mysterious ingredient that turns a mundane dish (or event or demonstration) into something unique and memorable.

Given the increasing centrality of cultural engagement to the ability to live a decent life and its underdevelopment in earlier incarnations of the welfare state, the cultural sector in the US can be taken as a case example of the challenge of achieving equity and inclusion in the new welfare state. Here, empirical work paints a picture full of challenges and opportunity.

The American cultural sector today—after a generation of marketization—is marked by a profound level of inequality, and all indications are that this inequality has continued to grow. In Philadelphia, for example, this is illustrated by the “differential mortality” of cultural organizations since the 1990s. As our research team discovered, over the past twenty years, the “mortality” rate of nonprofit cultural organizations was particularly high in low-income African American and Hispanic neighborhoods in Philadelphia.

In explaining the decline of cultural opportunities in low-income neighborhoods, a critical element has been a highly unequal distribution of funding by both the public and philanthropic sectors. In Philadelphia, during the first decade of this century, neighborhoods with concentrated advantage absorbed 96 percent of all philanthropic spending on the arts. During the same years, neighborhoods with concentrated disadvantage received only one percent and neighborhoods with a mix of advantages and disadvantages received only two percent of all funding—although they represented more than 60 percent of the city’s population. In New York City, although we lack data on change over time, our 2013-15 data revealed a similarly stark pattern in the distribution of cultural assets across the city’s neighborhoods in terms of economic wellbeing.

As the symposium organizers have noted, services tend to be unequally distributed compared to goods, at least in part because many services require recognition by consumers that they actual want them. Certainly one reason for the unequal distribution of resources is the distribution of “demand.” In low-income neighborhoods dominated by multiple dimensions of social exclusion, establishing a cultural space or forming a theatre group is often less compelling than the struggle for survival.

What’s remarkable is that in spite of these very good reasons for poor neighborhoods to ignore the arts, inequality and exclusion are not the only story. One phenomenon that has largely escaped the cultural policy world is the proliferation of cultural civic clusters. These low- and moderate-income neighborhoods are characterized by the concentration of a variety of cultural assets—nonprofit groups, for-profit cultural firms, resident artists, and cultural participants—that is higher than their economic standing would lead us to expect.

Our empirical work in several US cities demonstrates that these cultural clusters have become central to the link between cultural engagement and other forms of social wellbeing. In particular, when we statistically control for economic wellbeing, race, and ethnicity, we find rather significant relationships between concentrations of cultural assets and better social wellbeing along three dimensions—personal security, educational outcomes, and health. In other words, cultural resources are one of the elements of a neighborhood’s ecology that mitigates the effects of economic and social exclusion.

6 Looking ahead—culture and the geography of social wellbeing

To summarize. In recent decades, culture and the arts have assumed a more central role in the social wellbeing of residents and citizens, as both an intrinsic dimension of wellbeing and an ameliorative effect on other dimensions of social exclusion. Yet, at the same time, because of the geographic distribution of resources, the institutional structure of cultural services continues to reinforce inequality and social exclusion.

The question then becomes two-fold. First, how might the dilemma of unequal access to cultural opportunities be overcome? Second, what are the implications for the future development of social welfare services in general?

The dominant thrust for addressing these concerns within the US cultural sector over the past decade has been to promote cultural equity, which embodies values and policies related to diversity, equity, and inclusion. The statement of Americans for the Arts, an umbrella advocacy and research organization, is representative of this approach:

Cultural equity embodies the values, policies, and practices that ensure that all people—including but not limited to those who have been historically underrepresented based on race/ethnicity, age, disability, sexual orientation, gender, gender identity, socioeconomic status, geography, citizenship status, or religion—are represented in the development of arts policy; the support of artists; the nurturing of accessible, thriving venues for expression; and the fair distribution of programmatic, financial, and informational resources (Americans for the Arts 2016).

The cultural equity agenda generally seeks to ensure that the policies and governance of cultural organizations are increasingly diverse, with a particular emphasis on race and ethnicity. The focus of much cultural equity work has been assuring that boards and staff reflect the demographic profile of the communities served by the organization. This was a feature, for example, of New York City’s first comprehensive cultural plan completed in July 2017:

New strategies will support employment policies to increase diversity, equity, access, and inclusion in cultural staff and leadership through professional development and career advancement of cultural workers from underrepresented groups (New York City Department of Cultural Affairs 2017).

Although the plan also included extensive initiatives to expand cultural opportunities for low-income residents, it was these efforts to diversify staff and boards of trustees that drew the most attention. The only New York Times article on the release of the plan focused on the Mayor’s challenge to larger cultural organizations to do so (Pogrebin 2017).

Certainly, increasing the representation of under-represented demographic groups on boards and staffs is a positive step. Yet, in line with our earlier observations about the changing structure of racial inequality in the US, this approach is likely to benefit the more highly-educated and prosperous members of under-represented race and ethnic groups who have been able to take advantage of existing opportunities, while leaving the social exclusion of a larger proportion unchanged.

Instead, a capability-promoting approach to cultural policy would take as its starting point the importance of social geography to generating the neighborhood effects that are a critical component of social wellbeing. In so doing, a capabilities approach could focus on the links between cultural engagement and benefits for health, security, and schooling discussed above. Such an approach would likely begin with the civic cluster—low- and moderate-income neighborhoods that have greater cultural engagement than the majority of lower-income neighborhoods—and investigate the relationship between broader social and cultural participation and other indicators of improved wellbeing.

References

Americans for the Arts (2016). Statement on Cultural Equity. Washington DC: Americans for the Arts. Retrieved June 2018, from: https://www.americansforthearts.org/sites/default/files/pdf/2016/about/cultural_equity/ARTS_CulturalEquity_updated.pdf.

Dias, E., Eligon, J., & Oppel Jr., R. (2018). Philadelphia Starbucks Arrests, Outrageous to Some, Are Everyday Life for Others. Retrieved June 2018, from The New York Times (April 27, 2018): https://www.nytimes.com/2018/04/17/us/starbucks-arrest-philadelphia.html.

DiMaggio, P. (1991). Social Structure, Institutions, and Cultural Goods: The Case of the U.S.. In P. Bourdieu & J. Coleman (Eds.), Social Theory for a Changing Society (pp. 133-166). New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Harvey, D. (2005). A Short History of Neoliberalism. New York: Oxford University Press.

Katz, M., & Stern, M. (2006). One Nation Divisible: What America Was and What It Is Becoming. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

New York, City of, Department of Cultural Affairs (2017). CreateNYC: A Cultural Plan for All New Yorkers. New York: City of New York. Retrieved June 2018, from: http://createnyc.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/CreateNYC_Report_FIN.pdf.

Nussbaum, M. (2011). Creating Capabilities: The Human Development Approach. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Pogrebin, R. (2017). De Blasio, with ‘Cultural Plan,’ Proposes Linking Money to Diversity. Retrieved June 2018, from The New York Times (July 19, 2017): https://www.nytimes.com/2017/07/19/arts/design/new-york-cultural-plan-museums.html.

Stern, M., & Seifert, S. (2017). The Social Wellbeing of New York City’s Neighborhoods: The Contribution of Culture and the Arts. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, Social Impact of the Arts Project. Retrieved June 2018, from: https://repository.upenn.edu/siap_culture_nyc/1/.

Stern, M., & Seifert, S. (2013). Cultural Ecology, Neighborhood Vitality, and Social Wellbeing—A Philadelphia Project. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, Social Impact of the Arts Project. Retrieved June 2018, from: https://repository.upenn.edu/siap_cultureblocks/1/.

United Nations General Assembly (1948). Universal Declaration of Human Rights (Article 27). Paris: United Nations. Retrieved June 2018, from: http://www.un.org/en/universal-declaration-human-rights/.

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, UNESCO General Conference (2002). UNESCO Universal Declaration on Cultural Diversity. Paris: UNESCO. Retrieved June 2018, from: http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0012/001271/127160m.pdf.

Author’s Addresses:

Mark Stern, Prof. PhD.

University of Pennsylvania, USA

Urban Studies Program

stern@sp2.upenn.edu

Susan Seifert, PhD.

University of Pennsylvania, USA

Urban Studies Program

seiferts@sp2.upenn.edu