Can we draw a “realistic utopia”

toward publicly reciprocal welfare state?

–– A comparison of welfare programs between Japan and USA—

Reiko Gotoh, Hitotsubashi University

1 Introduction

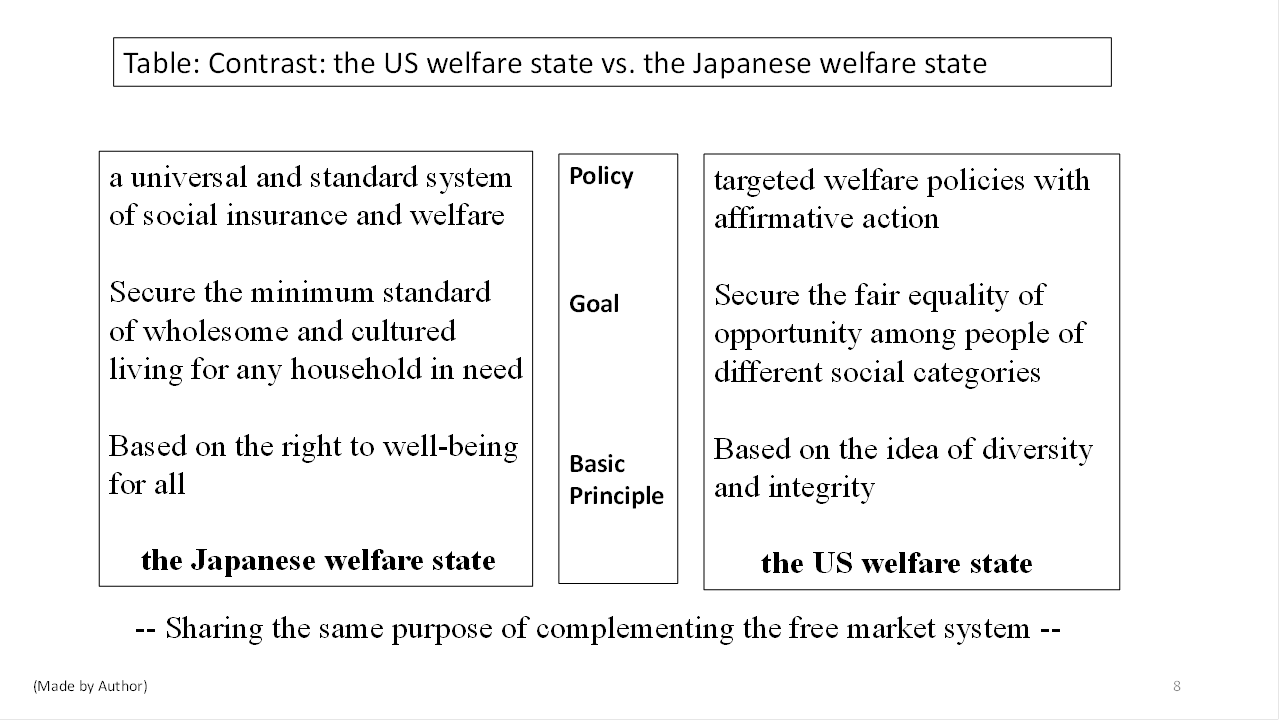

The USA and Japan have developed different types of the welfare state, sharing the same purpose of complementing the free market system. Both countries, however, seem to be facing very similar problems now. The USA welfare state has promoted an ideal of fair equality of opportunity. Yet, today, it seems that historical and social diversities are reduced to "a one-dimensional income table," which brings a fear of rank reversal through public provisions and a feeling of reverse discrimination in favor of particular social categories. In contrast, Japan has promoted a universal social insurance and welfare systems. Yet, the Japanese government has lastly begun cutting levels of public assistance to make the income table much smoother recently, which have been untouched as a safety net for almost 60 years after the Second World War.

The purpose of this paper to explore any underlying reason on this phenomenon, through exploring the movement of Hibakusha (atomic bombs victims) in Japan, which was the first example of seeking the state compensation paid for a specific reason different from the general public assistance.

The main task of this paper is, first, to critically reexamine the principle of economic rationality (including one-dimensional ordering through monetary index). The second is to identify a principle and scope beyond economic rationality in the movement of the “Hibakusha”.

Research Question is the followings. Shortly after the Second World War, Japan instituted an unconditional and general public assistance, based on the right to well-being for all stipulated in the new constitution. Why, then, did Hibakusha (atomic bombs victims) demand establishing a state compensation program based on the state's responsibility for the war, rather than relying on the general public assistance? Why do they claim not only the state compensation for the damages one has suffered but also the total abolition of nuclear weapons on behalf of the wider society or the distant future? What kind of rationales and scopes did this state compensation program with the aim of “No more Hibakusha” have in the process of rebuilding the welfare state in post-war Japan and in the world as well?

The first task of this article is to critically reexamine the principle of economic rationality (including one-dimensional ordering, conversion of 'consequences' into 'end to pursue,' etc.), which can prevail not only in the public assistance but also in the state compensation system. Our second task is to identify a principle and scope beyond economic rationality in the atomic bomb survivors' claim for "the state compensation with the total abolition of nuclear weapons." It also includes shedding light on the "blind spots," common to US and Japan, of the welfare state systems so far developed, mostly based on the principle of economic rationality.

Taking the conclusion very briefly in advance, it is pointed out, first, that economic rationality and the monistic logic of money, which underlies the welfare state systems, can sweep under the carpet various aspects and meanings of redistributive public provisions. There is a danger that the reason for claiming a state compensation by Hibakusha will be also wiped out if they too are placed somewhere in a monistic income table. This paper points out, second, that the Hibakusha’s demand for a state compensation based on the state's responsibility for the war, with the aim of “No more Hibakusha,” sheds light on the "blind spots" of the welfare state systems so far developed, mostly based on the principle of economic rationality.

With these conclusion, in order to help reconstruct the welfare state, this article is going to refer to a utopia of 'public reciprocity' that can possibly be realized by the following rule: Work and contribute if you can, receive if in need. It would be a society where all individuals respect their actual differences and carry through the ideal equality. The purpose of this article is to figure out those conditions that can make this utopia as realistic as possible.

2 Comparison between the Japanese welfare state and the US welfare state

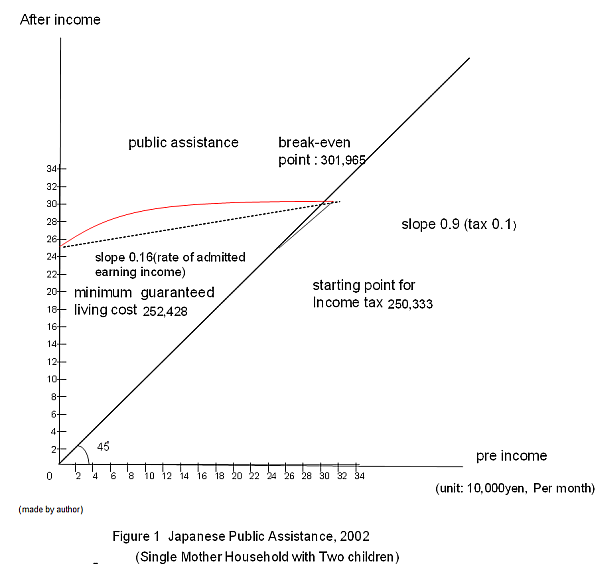

The characteristics of Japanese welfare state is summarized as follows. In Japan it is stipulated that “every citizen has the right to well-being, that is, to maintain the minimum standard of wholesome and cultured living.” (Japanese Constitution, Article, 25) The Japanese government therefore tried to achieve appropriate levels of benefits, while the "take-up rates" were kept low. The actual numbers of recipients were much smaller compared with the number of needy people eligible for receiving benefits. This is largely because the state adheres to the "principle of self-responsibility for application" and the "principle of supplementation" (by putting priority on using one's own assets and abilities and/or seeking support from family members).

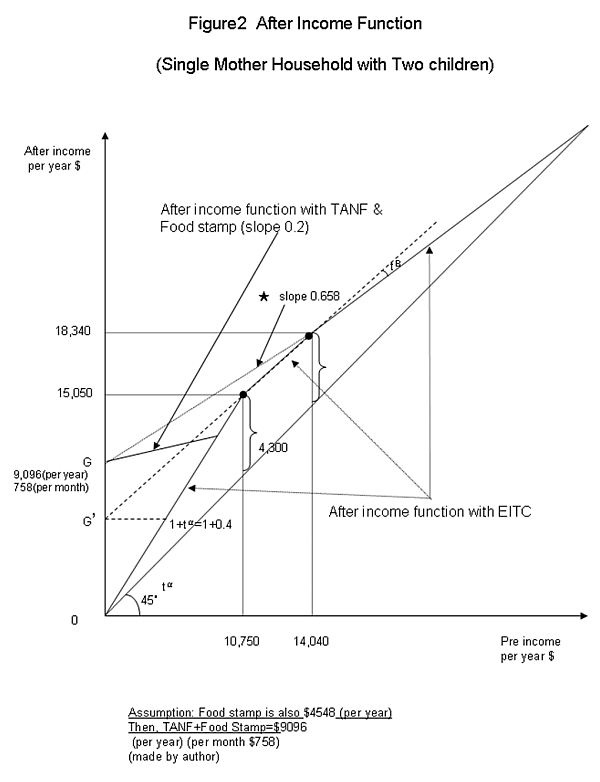

The characteristics of the USA welfare state is summarized as follows. In the US, levels of welfare payments were kept low and their eligibilities were limited to single mothers, severely disabled persons, and the elderly. Non-Hispanic young white men, for example, were not entitled even when out of work or very poor, whereas the working poor policies (such as the Earned Income Tax Credit: EITC) was expanded. With the ideal of fair equality of opportunity, the US has paid special attention to citizens in several social categories in order to correct historically and institutionally accumulated disadvantages they suffered. These efforts including affirmative actions should have included ethical and political messages as well as the state compensation, as demonstrated by the welfare right movement.

3 Ethical and political messages of the state compensation

Japan's constitution declares that all people shall have the "right to maintain the minimum standard of wholesome and cultured living" (Article 25). At the bottom of this safety net lies the public assistance system. The life protection act (public assistance) states that any citizen in need is entitled to receive necessary assistance and its purpose is to secure the minimum standard of living for all individuals and to foster their independent living (Article 3). The system is based on the following basic principles. (1) Equality and no discrimination (Article 2). (2) Distribution according to needs (Articles 1 and 9). Resources are to be provided not according to merits or contributions but according to individual needs). (3) Complementarity (Article 4). The other legal assistance programs and private capacities should be sought for first).

Article 17 of the post-war Japanese constitution led to the enactment of State Redress Act Law in 1947. It clearly states that “when a public officer who exercises the public authority of the State or of a public entity has, in the course of his/her duties, unlawfully inflicted damage on another person intentionally or negligently, the State or public entity shall assume the responsibility to compensate therefor.” It was this law that the Japan Confederation of A-and H-Bomb Sufferers, established in 1956, decided to make use of. The sufferers (called Hibakusha in Japanese) demanded for the Hibakusha Aid law based on the state compensation, as well as the "abolition of nuclear bombs." The Law Concerning Medical Treatment for the Victims of the Atomic Bombs legislated in 1957 was effectively the first example of the "state compensation" realized in post-war Japan, though it wasn't considered generous enough.

Compensations are intended to restore the original state, according to Aristotle's idea of "corrective justice." Corrective justice is usually realized when an agent who has benefitted unfairly (illegally or erroneously) return the benefit to the one who has suffered a loss. However, it is virtually impossible to restore the original state if atomic bombings caused irreparable damages. In this sense, the survivors, with their damages unhealed, can be regarded as permanent creditors who have legitimate rights to claim but cannot expect to be paid back. In contrast, the perpetrators become permanent debtors who can never atone for their mistakes.

However, the State compensation continues to send an ethical message that damages of atomic bombings was an unacceptable and intolerable evil. It also makes clear a political message that the state is responsible for its failure to stop evils (i.e., starting the war and abandoning the war victims). These messages represent the existence of ethical and political problems that should not be written off even after the 'original state' is restored completely.

This was precisely why Hibakusha demanded for a state compensation program different from the welfare benefit system. The first choice for the survivors, who had lost their houses, land, families, and jobs, was to receive welfare benefits in order to satisfy their urgent needs for housing, medical care, clothes, and foods. Subsequently, though, they rose to claim for establishing a program, separately from the public assistance. It led to comprehensive research on the whole picture of the damages of atomic bombings by looking at biology of the victims. What on earth have atomic bombs brought to the humanity and how have sufferers been fighting against every difficulties derived from atomic bombs. People began talking about their experiences, overcoming fear of discrimination and stigmatization.

However, the state compensation for the survivors might help transform them into holy martyrs and make this process a ritual (the "foundation for peace") so that the state can keep pushing their project of economic growth and social progress, as René Girard noted. Indeed, Hibakusha were treated, consoled, and even sainted as the "honored victims" on the whole by post-war Japanese society whereas politics tended to devote itself to fostering economic and political growth. Actually, it is pointed that there was a military purpose in studying consequences of nuclear weapons including aftereffects on survivors. Compensation for individual survivors in the form of medical service could be made into an excuse for developing more efficient nuclear weapons.

The Hibakusha movement demanding for the state compensation and the abolition of nuclear bombs was a battle against this political process of 'inclusion.' Their testimonies went beyond borders of Japan to international stages, including UN conferences on disarmament. They have made a strong argument that damages of atomic bombings cannot and should not be accepted or tolerated. This message was eventually crystallized into the simple slogan 'No More Hibakusha.' Demand for securing the minimum standard of living for individual survivors was transformed into one for the state compensation and accompanied by a call for abolition of nuclear weapons. This development has provided us with a new perspective to connect Article 25 (the right to well-being) and Article 9 (renunciation of war) of the Japanese constitution. This perspective culminated in “no more Hibakusha atomic bomb victims demand” in 1984.

Helped by the international opinion, the Hibakusha Aid Law was finally enacted in 1994 but it has many limitations, as has been pointed by Hamatani 2010. It does not have any clear advantage over other public assistance programs both in its design and execution of the system. As a consequence, the survivors continue their campaign for the “no more Hibakusha atomic bomb victims demand”. Its details will be examined in section 5. In the following we consider the significance of the Hibakusha movement in relation to the principle of economic rationality.

4 The state compensation and economy

Here we pay attention to the economic aspect of the state compensation. As we explained above, the principle of economic rationality can possibly distort ethical and political natures inherent in state compensation programs. This can be explained by a following simple example.

The state compensation is usually carried out by making up for lost interests caused by a particular damage. Diverse lost interests of physical or mental nature are converted into a certain amount in monetary terms and that mount is to be paid out to the sufferer. In the market economy, the amount paid can supplement the sufferer's income and enable him/her to buy various goods and services in the market. Thus, in the well-developed market economy, the state compensation is reduced to one source of supplementary income and their needs is reduced to general demand. Its unique nature tends to recede into the background.

This phenomenon is not a result of individual intentions, of course, but a natural consequence in the market economy system. However, the true value of the principle of economic rationality is in converting unintended results into intentional actions. This principle is embodied by the model of economic man (homo-economicus), where the result of receiving compensation for a particular damage might perhaps be regarded as an act to pursue acquiring income compensation. In other words, the social status of sufferer can have a risk of being regarded as an object to seek, for the purpose of private profit maximization. It can also give an illusion that a negative value of damage can be written off by a positive value of compensation.

These tricky assertions can deceive people into believing that from the beginning survivors could have compared and chosen between (a) escaping the damage of atomic bombings and (b) receiving compensation for the damage caused. The survivors too could be drawn into the realm of economic calculation of profits and losses, using the method of willingness to accept or willingness to pay, where they compare probabilities of certain risks and prospects of subsequent compensations.

This argument, probably unbelievable for the sufferers and survivors, is the standard approach adopted by mainstream environmental economics. This approach makes less clear absolute and evident evils of atomic bombing. The good and evil are supposed to represent different natures of things, not different degrees, and compel people to react differently, according to Hannah Arendt. However, the method of willingness to accept and willingness to pay compels people to blend the good and evil so as to maximize their expected utility. This argument can shake the foundation of the state compensation that damages of atomic bombs was evil that cannot and should not be accepted or tolerated. It can go further.

The monistic nature of money can provide an excuse to reduce the amount of compensation for the sufferers who make their best efforts to keep on going despite all conceivable difficulties. Suppose, for example, a woman suffered a damage of 100 but 10 is deducted if she survives, 30 if she can smile, and 40 if she can join a demonstration. Survivors keep living their own difficult lives and, by this, reminding us of the existence of the evil that should be avoided by the humanity and the strength of the humanity to resist the evil repeatedly. This is nothing other than a great contribution given by victims to our society and in no way a reason to cut the amount of compensation. It should deserve all gratitude and rewards.

Money enables us to compare, substitute, and exchange things of totally different nature. This function of money reflects our inclination to rank pleasures and pains of different nature on one dimension. Standard economics made use of this and constructed a rational model of utility maximization. This model can convert accidental events such as suffering the damage (natural, social contingencies: Rawls, brute luck: Dworkin) into alternative options (option luck: Dworkin). As Sen and Williams (1982) point out, this monistic approach has a danger of losing diverse meanings in exchange for its operational convenience. This approach tries to compare virtually incomparable things and tends to make obscure the inherent reason for state responsibility and the whole picture of the damages caused by atomic bombings. This, in turn, might cause a reversed envy by the non-sufferers towards the sufferers. Let me elaborate on this in the following section.

5 Public assistance and state compensation

The monistic logic of money can create an illusion of "positional continuity" between sufferers receiving state compensation and the low income earners who didn't suffer. Income levels, represented by a table of market incomes (before tax and subsidy) and disposable incomes (after redistribution), are characterized by continuous changes in the amount of money. Therefore, two persons with the same level of pre-redistribution income can rank differently in terms of disposable income, depending on taxes and subsidies. Whatever position one occupies in the ranking of pre-redistribution income, he/she would fear a rank reversal, after redistribution, with someone originally lower in the income table.

This is one of the reasons against

providing public benefits, as they can take away some people from the labor

market. No one would work, critics say, if poor workers are made worse off than

welfare recipients. To provide correct incentives, there have been pressures to

decrease levels of welfare benefits. They are kept lower than the levels of

minimum wage or minimum pension. Alternatively, their eligibility conditions

may become stricter by requiring more means tests and/or financial help from

family members rather than the state. The incentive can take the form of

working tax credits to induce more welfare recipients back to work.

In the well-developed market economy we tend to lose sight of original purposes of affirmative action or public benefits for disadvantaged people in special categories and look at economic interests only. There can emerge more people from a minority group, originally outside the labor market, who end up occupying higher positions in the income ranking. Here too, however, worked the monistic logic of money.

Especially, one of the most serious problems related to income compensation policy is the conflict between low income earners and welfare recipients. The former might envy the latter, who "cut in line ahead" (Hochschild 2016), because someone who must have been lower than oneself turns out to be higher at least in the income table after state compensation.

The working poor are heavily influenced by the monistic force of money and they also deeply 'internalize' it and apply it to locate other people in the same income table. Then they react against whatever income compensation policy that can benefit only certain groups of people and label it as a reverse discrimination. We have been observing this kind of reaction (for example, protests against income tax rises in 1978) ever since 1960s when policies to secure fair and effective equality of opportunity were adopted and expanded. Such reactions are getting escalated recently, perhaps thanks partly to president Trump!

As noted before, the state compensation system was meant to differentiate itself from general public assistance policies, by having specific reasons and clear justifications for the payment. However, the differentiation has become extremely difficult in the current social system where comprehensive tables for all levels of income are widely smooth and continuously, and the logic of economic rationality is hardly questioned.

The accusation of reverse discrimination can hurt the sufferers again, as a secondary damage, added to the original damage and social discrimination. Some sufferers can perceive a risk of the secondary damage and actually receive such merciless accusation. As a result, they may stay away from state compensation completely. They would reject the monistic logic of money in order to maintain the unique meaning of their own suffering, even though it is extremely risky to shoulder all their physical, mental, and material damages without receiving any public assistance. It is terrifying to face the physical, mental, and material disadvantages, unexpected additional losses, and deep anxiety caused by atomic bombing all alone. Now they are also exposed to uncertainties in the market and horrors of deprivation.

In fact, the survivors' battle against political inclusion by the state is one against the force of economic rationality at the same time. We look at details next.

6 The Hibakusha Aid Law

Hibakusha alley provides “no more Hibakusha atomic bomb victims demand” in 1984. It appeals two requirements: “Ban nuclear weapons!” and “Enact the Hibakusha Aid law!”. The former focuses on the future generation. The latter focuses on the past and the current generation. A clues to combine these two requirements is summarized as the following reasoning. Starting with a simple but true proposition based on their own experiences, that “It[atomic bomb] doesn't allow them to live or die as humans,” and having a recognition that the atomic bomb damage was "brought about by war, an action of the State," then we have a conclusion that “the enactment of the Hibakusha Aid Law (based on the Principle of State Compensation, with the aim of creating no more Hibakusha) would lead us to establish the right to reject nuclear war and its destruction.”

This reasoning seems plausible, since the obligation of the state not to repeat the atomic bomb damage reflects the right to reject nuclear war and its destruction. It combines several articles such as the article 13, the right to the pursuit of happiness[1], the article 25, the right to well-being and the article 9, forever renouncing war[2].

The Hibakusha Aid Law ought to provide for the following four main needs:

1. To provide state compensation for the damage caused by the atomic bombs, with the determination to create no more Hibakusha, that is, the state resolves not to make people "endure" the damage due to nuclear war, which is a prerequisite for creating no more Hibakusha.

2. To provide condolence money and survivor pensions on behalf of those who were killed in the atomic bombing.

3. To provide care of the Hibakusha, and provide medical treatment and recuperative care on the responsibility of the state.

4. To provide A-bomb victim pensions for all Hibakusha, with additional provision for those handicapped.

The greatest sufferers of the atomic bombings are those who died. “Condolence money and survivor pensions” would not only “express condolences for their unnatural deaths,” but would also “compensate the bereaved families who have been forced to live a long painful life because of the suffering and death of their relatives.” “A-bomb victim pensions” would be intended to “compensate for the damage, both physical and spiritual, and worries and difficulties in social life which the Hibakusha must endure throughout their lives simply because they happened to fall victim to the atomic bombings”.

Condolence money, survivor pensions and A-bomb victim pensions, payable to all Hibakusha, are crucial in establishing a compensation system different from current public assistance. They will represent the state’s recognition of and apologies for the responsibility and the fault of having deprived them of dignified deaths and lives as human beings. Then, they are expected to support the well-being of families and survivors through alleviating their guilty consciousness and excess self-responsibility.

In 1994, the Atomic Bomb Survivors' Assistance Act has been lastly established in place of previous two laws[3]. It is written in the preface that we would reconfirm the resolution for a Total Ban on Nuclear Weapons and never repeat the damage of the atomic bomb. The characteristics of the state compensation come to be clearer through the abolishment of income restrictions. It suggests that the compensation is made not for supplementing income shortage but for a specific reason.

However, the responsibility of the state for having started the war and long abandoned the victims has been faded behind. There is no reference to condolence money, survivor pensions or A-bomb victim pensions. Rather, it refers to promoting general aids over health, medicine and well-being as a responsibility of the state, favoring compensating health damages derived from radiations. In the end of the above document of Hibakusha’s requirements, it is written that “Building a fortress to prevent mankind from ever repeating this tragedy--- we consider this our mission imposed by history on those who survived the atomic bombing. Fulfilling this mission is the real heritage we can pass on to coming generations”.

In 2017 the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons was adopted in UN. Hibakusha played a great role by expressing themselves as witnesses of the atomic bomb's unrecoverable damages. Yet, the Japanese government refused to make a positive vote. The political wall against "no more Hibakusha" has been still high. However, if they withdraw their basic demands and keep silent, they might well be at the mercy of the monistic logic of money. Let me conclude this paper by taking this double-bind situation seriously.

7 Conclusion

Atomic bombs caused irreparable damages to Hibakusha. Their suffering, pain, sadness, anger, and hatred grew mercilessly as they continued to live on. Their voices remind us of what we should care about and what we now know we could have avoided. They can clearly tell us what we have to see beyond the thick wall of politics and behind a summary table of income levels.

As we described in the beginning, the US and Japan have developed different types of the welfare state, while sharing the same purpose of supplementing the free and competitive market system. Based on the ideal of diversity, the US welfare state has tried to identify typical social categories and secure "fair equality of opportunity" among people of different categories. In contrast, the Japanese welfare state, with apparently homogenous citizens, has tried to secure the minimum standard of living for all individuals (households). Japan's public assistance was expected to provide a 'safety net' against income shortages due to unemployment, disability, illness, injury, or care for family members. More frankly, it was also meant to protect working citizens from crimes.

The Hibakusha movement, which claimed the state responsibility for the war and demanded for the total ban on nuclear weapons, sought a compensation program different from the universal public assistance. It became the first example of state compensation paid for a specific reason. This paper has pointed out that economic rationality and the monistic logic of money can sweep under the carpet various aspects and different meanings of the state compensation. It could create an illusion of exchangeability of circumstances, bring a fear of rank reversal in the income distribution, and cause a reverse discrimination and a reverse envy. The US today shows us the reality where historical and social diversities are reduced to "a one-dimensional income table" and endless battles are fought on that stage.

Recently the Japanese government has begun cutting levels of public assistance, which were supposed to provide a safety net and untouched for almost 60 years after the Second World War. Instead, they have been expanding social security programs for an increasing number of 'non-regular' workers and promoting working campaign for the young, women, and the elderly. On the whole, reforms are being implemented to make the income table smoother. The reason for claiming state compensation by Hibakusha will be wiped out if they too are placed somewhere in this income table.

However, the well-being (living conditions) of Hibakusha themselves might be ignored if they reject state compensation and concentrate on delivering ethical and political messages alone. This paper concludes by considering this double-bind problem.

"Hibakusha" is a social category. In a homogeneous society, putting oneself in a specific category and calling it an absolute evil to be avoided can have a risk of being discriminated. There might have been a strong pressure to conform to the homogeneity of "Japanese citizen." Nevertheless, they tell us a lot by holding the state to account for the war and demanding the abolishment of nuclear weapons. If an atomic bomb is to be used again, our future generations would be exactly like Hibakusha, who are deprived of "deaths and lives as human beings."

They are, in a sense, doomsayers from the avoidable future, shouting "No More Hibakusha" to warn us today. To provide social security for them is to show our gratitude for their wisdom, devotion, and contribution. Here is the inherent significance of state compensation that cannot be reduced to a one-dimensional income table.

What we have to do now is to recognize potential situations where "deaths and lives as human beings" are deprived, discuss necessities and possibilities for various compensations and benefit payments, and reconstruct the welfare state to cover them as a whole.

One of the basic principles of the society we conceive of is what we call "public reciprocity," with a common rule: Work and contribute if you can, receive if in need. It is based on the market economy where people work and contribute (Gotoh 2009). As such, it is no different from the current welfare state. Yet, its social goal is not limited to securing living for those alive today, but it covers also the dead and future generations. Then we will have a wider and richer understanding of the meaning of 'contribution.' It will be a society where individuals respect their actual differences and achieve the ideal of equality. This is the realistic utopia we have in mind.

References

Dupuy, J.-P. (2015). A Short Treatise on the Metaphysics of Tsunamis. East Lansing: Michigan State University Press.

Gotoh, R. (2001). The Capability Theory and Welfare Reform. Pacific Economic Review, 6(2), 211-222.

Gotoh, R. (2004). Well-Being Freedom and The Possibility of Public-Provision Unit in Global Context. Ethics and Economics, 2, 1-17.

Gotoh, R. (2009). Justice and Public Reciprocity. In R. Gotoh & P. Dumouchel (Eds.), Against Injustice? The New Economics of Amartya Sen (pp. 140-160). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gotoh, R. (2014). The equality of the differences: Sen's critique of Rawls's theory of justice and its implications for welfare economics. History of Economic Ideas, XXII, 133-155.

Gotoh, R. (2015). Arrow, Rawls and Sen: The Transformation of Political Economics and the Idea of Liberalism. In P. Dumouchel & R. Gotoh (Eds.), Social Bonds as Freedom (pp. 259-284). New York, Oxford: Berghahn Books.

Gotoh, R. (2015). What Japan Has Left Behind in the Course of Establishing a Welfare State. Proto Sociology, 32, 106-122.

Hochschild, A. R. (2016). Strangers in Their Own Land — Anger and Mourning on the American Right, A Journey to the Heart of Our Political Divide. New York: The New Press.

Author’s Address:

Reiko Gotoh, Prof. PhD.

Hitotsubashi University, Japan

Institute of Economic Research; Research Division of Theories in Economics and

Statistics

reikogotoh@ier.hit-u.ac.jp