Social Investment Bonds in the European Context

Norbert Wohlfahrt, Lutheran University for Applied Science Bochum

1 Preleminary Note: a new understanding of social policy

The concept of social policy as investment is quite different to the traditional understanding, after what social policy can be understood as a compensatory reaction by the state to – in a wide sense – reproduction problems of labour commodity. In this concept social policy is a reaction to social conditions, which produces (temporarily or permanent) individual needs, that cannot be solved by the particular power of the specific person. Social services are typically individual related benefits, basing on individual demands and they are addressed with the principle of help by themselves.

In the new concept social policy can be viewed as investment, aligned to yield a good return. In the new understanding of social policy resources of the social state cannot be considered as individual consumption, needed for the protection of personal reproduction, they have to be viewed as investment in human capital.

This concept of social policy strengthens the rise of cost-benefit calculations, which no longer provide a basis for the legitimation of public spending. Now the proof of a good investment is on the agenda and for this the yield of return must be assessed as a measurable quantity. The orientation towards measurable success – and for this the term impact should be used – belongs fundamental to the agenda of the new understanding of social policy. This is the basis for innovative approaches in financing social services and one of these approaches is the Social Impact Bond.

Originally the concept of a Social Policy, financed by Bonds, was published 8 years before the financial crisis by Ronnie Horesh, who argued that government spending is large and growing and big government is a threat to liberty. Horesh critizises the contract management model of the new public management, it is „not radical enough, and the reforms have been constrained by their institutional structure“ (p. 77). The substantial benefit of a social bond system is in his words: „Concentrating (...) on outcomes, rather than activities, the Bonds would allow far less room for ambiguity or deception than the current system“(p. 121). The message of Ronnie Horesh is very clear: the welfare state is a miserable failure and has to be substituted by the implementation of market mechanisms like a bond based social policy.

2 The Idea of Social Impact Investing

In 2018 Social Impact Bonds (SIBs) are established in more countries and in more policy sectors than ever before. The SIB approach, which includes a three-way relationship between a public sector commissioner, service provider and independent investor has been pursued in the belief that it can unlock a range of benefits including improved cost effectiveness, innovation and improved social outcomes (Gustafsson-Wright et al. 2015).

Social Impact Bonds are part of the updraft field of impact investing. After the financial crisis of 2008 impact investing is getting more and more important as a strategy in which investors are trying to combine social benefits with financial income return. A report of the Boston Consulting Group arrives at the conclusion that the market of impact investing is growing every year at 38% at which several developments are responsible for this:

· a growing market share of private investors in relation to public funding;

· a general development towards more risky models of measurement contracts like payment of results

· a growing specialisation of intermediaries in the economic sector on investment strategies in the public sector and investment by results.

Social Impact Bonds are a special area of outcome contracts and they are discussed as a consequence of 2 shortcomings in the delivery of public social services.

„1) existing services are not delivering the quality of outcomes needed for service users; and 2) there is an appetite to create significant change in the way services are designed and delivered” (GO Lab 2017, S. 6)

Let me give you a short survey about the structure of SIBs in Europe

a) Today over 40 SIBs are implemented or already finished. A great problem for the investors is the relatively small amount of money, which is usually necessary to establish one SIB. In the Netherlands and in Portugal Fonds for SIBs will be established, the Fond in Portugal is about 150 Billion Euro. Worldwide dozens of SIBs are in development, for example in Mozambique to fight Malaria, in Uganda SIBs for education and family planning are intended.

b) The types of payment are different in any SIB but empirical research shows a difference between two types of payment: in the first categorie the contract partners take prizes for every participant in the Bond and the payment is every month, quarter or on an annual basis. Many of the outcome measurements in these Bonds are Outputs and not Outcomes, they evaluate the results of each person included in the Bond. The contract partners measure the outcomes of their result on the basis of the contracted conditions.

The second type of payment the evaluation basis are the outcomes by a group of participants compared to a control group with no-participants. The payment is at run time of the contracts and the SIB-contracts include payments on behalf of a percentage change in the outcome matrix. In the Netherlands the conditions of payment are not public.

c) The methods to measure outcomes base upon outcome matrixes, which reflects the requirements of the stakeholder that are included. For SIBs with payments for each person who participates in the bond, often administrative data are used to define the outcome data. In SIBs, where evaluation is based on a control group design more complex evaluation designs are necessary. Some of these SIBs are using a combination of outputs and outcomes on an individual level and outcomes compared to other groups. In several SIBs the outcomes are defined on the basis of historical data of the public administration.

d) All returns in the existing SIBs depend on outcomes and each one has its own risk-profile, so it is not possible to compare the return between all existing SIBs. But each SIB establishes a maximal return of investment for the investors, also known as maximal contract value. The average interest rate is different from country to country, in Germany it is at 3 %, in Great Britain it is about 7%, at which the maximal annual interest rate for senior investors differs from 9 to 15% and for Subordinate Investors in one SIB up to 30%.

3 From Output to Impact: a new understanding how social services work

If we look on the discussion about effects in social work and social services we can distinguish between 3 levels of results or quality dimensions:

· the Output – it describes the quantity of services in a special area of social problems

· the outcome – it describes the dimension of the results quality, which can be caused by intended or not-intended effects of a special intervention and

· the impact – it describes the results which can explicitly be attributed to a specific intervention.

Social Impact Investing is a kind of portfolio strategy which focusses on a special form of results – the impact. If we look at strategies of capital investment by private investors we need a benchmark, who gives the investors information of priorities of investment and alternatives of spending their money. The best benchmark is money. You can convert the quantity of results of social services in money and if you compare this with the amount of money needed for the intervention (input), investors get information of the rate of return for a special kind of social intervention. The concentration of the discussion about effects in social services is only understandable, if we realize it as a consequence of a new concept of social policy, in which investors (public or private) want to achieve a return by their social investment. This return can be a social return or a monetary return.

If we look on Social Investment Bonds in Europe we can distinguish between two types of Investment Bonds: a continental european model – in this model the rate of interest is not so important. The most important issue for the investors in this model is the spread of the idea of impact-orientation in the financing of social services. In consequence of this idea SIB-projects cannot fail. They are always win-win projects. Even if the targets of the project cannot be achieved, the findings are important for the future design of social service policy. Policy makers learn, that funding for such forms of intervention cannot occur on a regular basis. Such projects are often financed by foundations with anthroposophical background.

Another type of SIB is the anglo-saxion model. In this type of SIBs investors are looking for a high interest rate (up to 12.% in some SIBs) and they view the social sector as an area for capital investment. The level of the interest rate reflects the risk to loose the whole investment if the outcomes cannot be achieved (Burmester/Dowling/Wohlfahrt 2017).

The original idea of Impact Investment – to pay only after the end of the projects – is modified in several SIBs and payments will be carried out during the implementation process. These procedure decreases the risk of the investment, but this arrangement has negative consequences for the interest rate the private investor can achieve In other SIB-projects a loss of the whole investment is impossible.

4 The challenge of designing impact contracts

A special challenge in the development of SIBs is the definition of the required results and how they can be achieved. The contracts have to be designed in a way that they avoid cherry picking or other possibilities of goal achievement can be excluded which are not intended by the public administration. If measurable results are defined they have to be assessed. In the perspective of the public sector exists a general parameter: „The value of the outcomes to the commissioner is very clear in terms of savings made on payment of benefits, irrespective of the cost to the provider of achieving the outcomes“ (GO Lab 2017, p. 9).

Of course costs are important for the service deliverer, because without expected cost recovery they will not participate in a SIB. To give an example: For the determination of the prices for example in Great Britain we observe 3 types of contract tendering: „1) (…) the commissioner proposes a payment framework and looks for providers to bid on the quantity of outcomes to be delivered, or 2) bidders propose a discount on the value of the outcomes, or 3) to receive financial proposals from providers against an outcome framework“. In some SIBs the prizes for defined results follow cost-benefit analyses and in other SIBs the service deliverer defines the results and how they can be achieved. In these SIBS the service deliverer is part of the contract management.

In all SIB projects we interviewed in our study[1] there is a strong link between the issue to improve the outcomes and the saving of costs. In the Essex SIB, for example, the primary outcome metric on which success is measured is the aggregate number of “care placement days saved” against a baseline historical comparison group. In the Essex Social Impact Bond paper it is noted: “The outcome valuation for a SIB is the average public sector costs saving resulted from an improvement in the outcome. It should be noted that for the purposes of analysing the potential returns to investors, the outcome value is narrowly defined in terms of the cost savings accruing to specific public sector budgets” (Big Society Capital, p. 7).

SIBs are not appropriate for any kind of social intervention. A reason for that are the relatively high costs for the implementation and for the execution. If social service deliverer deal with SIB contracts there is no doubt that this has severe consequences for their professional work. The often mentioned advantage of more freedom in problem solving is opposite with the disadvantage that their work is fixed on the targets formulated at the beginning of the service process. This arrangement is in a professional perspective not unimportant. In fact the personal needs of the target group in these contracts are only an insignificant dimension for the results that have to be achieved.

5 Consequences of Impact Bonds for professional social work

In fact, social work in SIBs cannot be open ended. The professional self-conception of negotiating the targets of the intervention with the clients or looking for alternatives of problem solution cannot be realized. One example for that is a SIB who works with people who are mental handicapped.

Answer: „Our Model is an open door model, so that in two years time, someone wants to change jobs, they can come back and say: „can you help me, I want a better paid job or change jobs“

Question: „But the commissioner or the investor, they are not interested in this long-term-perspective?

Answer: „No they are not. We still have to report the targets, that are attached to money and then then are targets that are just for reporting, as a evidence. So there is a split. We still report on the number of people that we work with, as a part of the engagement, but it`s no money attached to that.

Question: „And who decides, whether you have reached the target and the payable target?

Answer: „It`s very clear, we know how many we have to get, so we have to get eleven people into work each month. So if we get not 11 people into work we know we haven`t reach the target…. So evidence-collecting is one part of payment by results that is hard. I think if you speak to other providers like us, that it´s kind of a ongoing issue that tries to find a way of how do we make sure we collect the evidence of outcomes. Because without the evidence they won`t pay.

That`s reality and we cannot going down into the happy days 20 years ago, when you applied to a grant and you basically said: „I want to do some good work“. And they gave you the money. That´s a long time ago. They now need a very clear evidence base, why you are doing work this way and that work is going to have positive outcomes beyond people just feeling better. And this impact bond provides a way of saying we put this money in but we`ll get these outcomes out. I am a cynic. I know it´s around cost-savings. This is a way of saving money, or making money being used in the most effective way for the funder”.

5.1 Consequences of SIBs for the public administration

Projects of Impact Investing operate under a certain condition: they have to reduce costs for the public administration. The surplus for the society, that has to be generated in these investments, is in the end the hope to spend less money for the (local) social state. This is one of the explanations, why the integration into work is in many SIB projects the dominant target. In a general way results are the basic instrument to reduce or substitute transfer payments. This is the basis of the social investment perspective in all SIBs. Because the public commissioner wants to reduce costs, a new problem is getting important: the accountability of possible savings to the certain department or administrative level of the social state. It may be, that savings will benefit other administrative units than the contracting unit, who has to pay for the results plus the interest rate. A consequence of impact investing may be a new arrangement for the budgets of different administrative units. SIBs are working as a pressure to reorganize the public sector in the way of looking on results and not on outputs. The product orientation and output performance of the new public management model is no longer the dominant issue for the modernisation of public administration, because it leads to a fragmented administration and is restrictive against the strong combination of money (budgets) and impact.

For the public administration impact investing is a tool to get money for the solution of social problems. In times of austerity this is an attractive way to mobilize private investments for social problems beside the regular programmes. In the view of the public commissioner it is no problem to deal pragmatic with one of the fundamental methodological demands of the impact investing model: the causal accountability of results to the social intervention. Our research shows, that in most empirical examples the accountability of results is not possible. For example in SIBs dealing with homeless people it is very difficult to decide, which effects are caused by a specific intervention and usually different teams of professionals are working with homeless people, depending of their situation of life. This leads to the question: Is the achievement of the result: „placing in a hostel for the homeless“ caused by the team financed by the SIB or is it perhaps caused by the (in the SIB-Design not controlled) intervention of the police?

It is evident that the results cannot be

clearly attributed to the intervention and it is evident, too, that the

question concerning the amount of costs that saves money for the public

department cannot be answered. The measures, to give an example, who leads to

the consequence of ending public social welfare for young people can be caused

by different benefactors (local state, education system, changing of private

circumstances etc.) and there is no evidence, that it has been caused by the

performance of the social entrepreneur.

Even in SIBs dealing with quasi-experimental designs the comparability of the

results between control group and intervention group is an ongoing problem. It

is not possible to have control about all the imaginable effects on the result,

so that only the intervention makes the difference. The demand of the Impact

Investing, that public and private investors in the future make their decisions

on the basis of „substantiated evidence instead of the basis of friendly

haluzinations“ (Shaw and Volz 2017) is a nice polemic formulation, but it

reflects not the reality of social impact investing.

6 Conclusion: Using private money for the solution of market-generated problems

„Pay for success (PFS) is a type of social

impact investing that uses private capital to finance proven prevention

programs that help a government reduce public expenditures or achieve greater

value” (Lantz et al. (2016). One of the key points of social investment

strategies is the reintegration of people in the labor market. Our research

underlines this. Many SIBs are placed in areas with target groups with special

problems of integration in the labor market. To solve these problems new and

innovative forms of intervention (even with higher costs than the regular

intervention programs) are financed. The replacement from the transfer system

has in all SIBs an outstanding importance. Some of the SIBs in our research are

dealing with target groups which are traditional not in the focus of programs

of labor market integration. In a supply side economy the integration into work

is the spirit of social service delivering.

To come to a conclusion: Social Impact Bonds are not only an instrument of

financing social services in a new way. Let me outline 4 other effects we can

observe:

· SIBs are working as a pressure to reorganize the public sector in the way of looking on results and not on outputs;

· SIBs support the process of monetarising outcome data;

· SIBs accelerate the process of market liberalisation in the social service sector;

· SIBs have innovative effects of the quality of public services, because they are dealing with new target groups, new ways of delivering social services and new areas for financing social services.

Social Impact Investing is used as a learning platform by the local state and the public social service management to develop tools of defining outcome criteria and force social work and social service deliverer to fulfil administrative requirements. The public administration uses private investors to bare the risk of impact orientation and – of course – the private investors want money for this risk-transfer.

The cooperation between private investors and the local social service administration makes it important for them to understand the logic of cost calculation by private investors, because they expect compensation for taking the risk of not achieving the defined impacts. Public commissioners have to know more about strategies of capital investing and they need information about the conditions of markets and prizes for contracts. With such data a certain kind of competition between potential investors can be generated and the bargaining power of the public social service management can be encouraged. In this way social impact investing is an ongoing process of transforming the political economy of social service production towards more market-orientation, against the traditional view on profession and professionalization and towards a social service state, which is handling the social problems of a capitalist society as a problem of mobilising private money for a better performance of the public service sector. Impact investing demonstrates, that in the view of a bond-financed social policy not only the old welfare state with its transfer payments has failed, but also the traditional social service system must be changed towards more “productivity”. This leads to a perfect quid pro quo: the costs for those out of work with specific social problems have to be reduced to make them productive for the labour market. What works? Getting work – and this is the impact of the social service state.

References

Burmester, M., Dowling, E., & Wohlfahrt, N. (Eds.) (2017). Privates Kapital für soziale Dienste? Wirkungsorientiertes Investieren und seine Folgen für die Soziale Arbeit. Baltmannsweiler: Schneider Verlag.

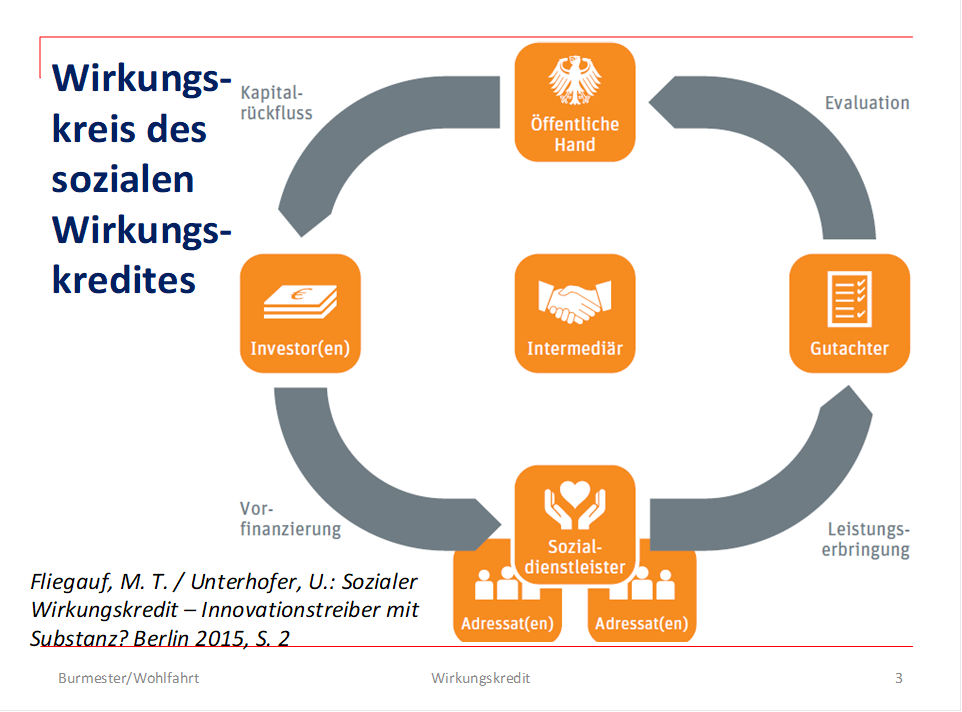

Fliegauf, M.T., &

Unterhofer, U. (2015). Sozialer Wirkungskredit —

Innovationstreiber mit Substanz? Retrieved November 2018, from stiftung

neue verantwortung:

https://www.stiftung-nv.de/sites/default/files/impuls_soziale_wirkungsfinanzierung.pdf.

GO Lab [Government Outcomes LAB] (2017). How to Guide. Contracting and Governance. A technical guide to contracting and goverance practices in outcome based commissioning. Retrieved November 2017: http://golab.bsg.ox.ac.uk/sites/golab.bsg.ox.ac.uk/files/2017-10/GoLabGuides-ContractingAndGovernance%5B1%5D.pdf.

Gustafsson-Wright, E. (2016). The Netherlands leads again in social innovation with announcement of fifth social impact bond. Retrieved November 2017: https://www.brookings.edu/blog/education-plus-development/2016/06/09/the-netherlands-leads-again-in-social-innovation-with-announcement-of-fifth-social-impact-bond/.

Lantz, P. M., Rosenbaum,

S., Ku, L., & Iovan, S. (2016). Pay for Success and Population Health. Early Results From Eleven

Projects Reveal Challenges And Promise.

Retrieved Decembre 2016, from Health Affairs 35(12):

http://content.healthaffairs.org/content/35/11/2053.full?ijkey=2gRvZV98U/oRY&keytype=ref&siteid=healthaff.

Shaw, S., & Volz, U. (2017). Was ist Wirkung? Retrieved April 2018, Benckiser Stiftung: http://www.benckiser-stiftung.org/de/blog/what-is-impact.

Author’s Address:

Norbert Wohlfahrt, Prof. Dr.

Lutheran University for Applied Science Bochum, Germany

Department for Social Work, Education and Diaconia

wohlfahrt@evh-bochum.de