Connections Matter: Family Centers and German Social Policy

Onno Husen, Leuphana University Lüneburg

Philipp Sandermann, Leuphana University Lüneburg

Introduction

For the past decade, debates about the family have clearly gained importance in German social policy. One argument often used to explain this growing interest is that families need more direct support to meet their daily challenges, due to changing labor market conditions, gender roles and life courses. The German Federal Ministry for Family Affairs’ seventh German family report published as early as in 2006 made this argument for example (BMFSFJ, 2006). This very general argument, embracing all families, gains its power primarily against the background of continued low birth rates in Germany.

At 1.47 children per woman (2015), the German birth rate is one of the lowest in the world. This phenomenon is not new. Birth rates in Germany started to drop in the late 1960s, resulting in a demographic change that has been regarded as the paramount challenge for the “conservative” German welfare state (Esping-Andersen, 1990; Stoy, 2014). It proved possible to partly cushion that challenge through temporary increases in immigration. However, over the last few decades immigration quotas have varied considerably (Statistisches Bundesamt, 2014a), and the idea of a more positively defined immigration policy has only just begun to gain ground (Martin, 2004, p. 250), recently in combination with Germany’s comparatively liberal refugee policy (Bauder, Lenard, & Straehle, 2014). It is thus hard to make reliable estimates about the past, let alone the future, impact of immigration on demographic change in Germany.

Available research on family demographics shows that the number of families with minor children decreased from about 9.4 million in 1996 to about 8.1 million in 2013. Along with this development, family models have changed. The percentage of married couples dropped from 81.4 per cent (1996) to 69.9 per cent (2013) due to an increase in unmarried couples (4.8 per cent in 1996 to 10.0 per cent in 2013) and single-parent families (13.8 per cent in 1996 to 20.0 per cent in 2013) (Statistisches Bundesamt, 2014b).

It was to react to these developments politically and to officially “support families” (Meyer-Ullrich, Schilling & Stöbe-Blossey, 2008) that family centers were placed on Germany’s social policy agenda. Programs of this kind have been promoted at the level of the Federal Republic’s 16 constituent states and of the municipalities. In terms of institutional structures, most family centers are combined with classic day-care centers, but aim to extend their services to the whole family. Their goals are to provide education and care for children, to offer courses and counseling for parents, and to act as a hub for community services.

Family centers are neither a uniquely German nor a wholly new phenomenon. Institutions offering similar services have been established in various European countries for some time. For instance, there are “children’s centers” in the UK (Jüttner, 2010) aiming to give direct support to families. They have been framed in a public discourse that appears to be comparable to the German one, constructing families as entities in need of enhanced support (Gillies, 2005). Other models similar to the German idea of family centers are, for example, the Opvoedingswinkel (Parenting Shop) in Belgium, the Centrum Jeugd en Gezin (Center for Youth and Families) and the Spelen, Integreren en Leren (SPIL) Center in the Netherlands, and the Family Support Hub in Northern Ireland (Eurochild, 2012).

On the face of it, these comparisons seem to indicate a clear social policy trend in Europe towards specialized institutions that directly support families. However, the German case of family center policy in the country’s most populous state, North Rhine-Westphalia, offers some valuable insights that suggest this alleged trend is in fact not a trend, or even turn, towards direct family support services.

Instead, this article argues that particular assumptions on families have been advanced in recent German social policy on a broader scale, and that these assumptions underpin important connections between family services and traditional interests of social policy in Germany. It is because of these traditional interests, and not because of a turn towards policies, which directly support families, that there has been a broad implementation and spread of family centers in Germany in recent years.

To develop this argument, the paper will answer the following questions: 1. To what extent can we speak of an increase in the political importance of family center programs in Germany? 2. Regarding the case of Germany’s most populous state, North Rhine-Westphalia, how much have family centers increased on the institutional level? 3. Exactly how have family centers in the state of North Rhine-Westphalia been linked to particular assumptions on families through political promotion documents and to what extent do these assumptions connect family centers in North Rhine-Westphalia with traditional interests of German social policy? Finally, 4. What conclusions do these findings allow regarding the basic question of change and continuity in German social policy and social work?

Over the course of a careful exploration of these four questions, we aim to show why, and with what results, family centers were able to take root in Germany – seemingly against all the institutional odds.

1 Family center programs in Germany

By and large, the idea of family center programs in Germany has been linked to two public debates, firstly the perception already mentioned that families are facing increasing challenges (Diller & Schelle, 2009, p. 9), and secondly a broad-based discussion on early childhood education in the aftermath of the first published results of the PISA study (Rietmann & Hensen, 2008, p. 9). Family center programs evidently respond to these public debates. Their twofold goal, of supporting children and parents alike (Diller, 2010; Diller & Schelle, 2009; Müncher & Andresen, 2009; Oberhuemer, Schreyer & Neuman, 2010), takes concrete shape as a holistic political strategy: family centers try to provide easily accessible services for families as a whole and to operate as a hub for community services (Oberhuemer et al., 2010, p. 180), providing education and day-care for children as well as training and counseling for parents.

The term “family center” is a conceptual one that should be regarded as a broad programmatic category. In practice, the ways in which German family centers deliver their services vary considerably. For example, many services are provided not by the family centers themselves, but by cooperation with social service organizations based in the community. Depending on their profiles, the modalities of family centers’ cooperation with other organizations may also vary significantly. This shows that family center programs in Germany leave space for diverse ways of institutionalization in the field (Diller & Schelle, 2009; MGFFI, 2008; Rietmann, 2008; Textor, 2008).

This diversity can in part be attributed to differences in the implementation and funding of family centers. In eight of Germany’s 16 states, family center programs have been implemented and funded through statewide pilot projects and support programs. In almost all of the other eight states, there are at least some municipalities that have funded and supported family centers (see Table 1).

Table 1: Support for family centers in Germany

|

State |

State’s measures to implement family centers |

Comments |

|

Baden-Württemberg |

No |

The Baden-Württemberg government’s 2011 agreement states the general need to establish family centers, but leaves implementation to the municipalities. Municipal pilot projects do exist. |

|

Bavaria |

No |

Municipal support programs do exist, for instance in Munich. |

|

Berlin |

No |

A support program is planned on the state level. However, some institutions already exist, with various funding sources. |

|

Brandenburg |

Yes, pilot project |

The first pilot project ran from 2006 until 2009 and the second from 2009 until 2012. |

|

Bremen |

No |

Municipal pilot projects do exist. |

|

Hamburg |

Yes, support program |

|

|

Hesse |

Yes, support program |

|

|

Mecklenburg-Vorpommern |

No |

|

|

Lower Saxony |

No |

Municipal support programs do exist, for instance in Hannover. |

|

North Rhine-Westphalia |

Yes, support program |

|

|

Rhineland-Palatinate |

Yes, support program |

Provides initial funding for the first three years. |

|

Saarland |

No |

Individual institutions do exist. |

|

Saxony |

Yes, pilot project |

The pilot project ran from 2001 until 2007. |

|

Saxony-Anhalt |

Yes, pilot project |

The pilot project ran from 2007 until 2011. |

|

Schleswig-Holstein |

No |

Municipal pilot projects do exist. |

|

Thuringia |

Yes, pilot project |

The pilot project started in 2011. |

Source: Schlevogt, 2012, pp. 7–8

Table 1 shows on the one hand that there is great variation between the 16 states regarding the modes and extent of funding and support for family centers. On the other, it suggests that the concept of family centers holds some appeal for state-level policymakers and municipal authorities, and has generally become established as an element of German social policy on both these levels.

2 The institutional spread of family centers in North Rhine-Westphalia

Although it is relatively easy to demonstrate presence of the programmatic idea of family centers in recent German social policy, to date there have been no statistics on the institutional expansion of family centers in Germany. In this section, we focus on the institutional spread of family centers in one of Germany’s states, North Rhine-Westphalia. Given the variety of family centers across the German field, we are aware that this is no substitute for a complete overview of family centers in Germany, but the specific case of North Rhine-Westphalia can provide worthwhile information for three reasons. First, it is the most populous of the German states, with about 22 per cent of the total population, and therefore represents a meaningful segment of the country. Second, it has a statewide support program for family centers, which makes it possible to identify and directly compare the relationships between the institutional spread and political promotion of family centers. Third, the expansion of family centers in North Rhine-Westphalia is relatively advanced, which may even make it a kind of showcase for contemporary developments throughout Germany.

The expansion of family centers in North Rhine-Westphalia was initiated by a pilot project launched by the state government at the beginning of 2006. The program ran until August 2007. Initially, 257 of the 1000 day-care institutions that expressed an interest were chosen to be part of the project (MGFFI, 2007). The selection criteria were that the institution must agree to continue providing its regular day-care services for children and additionally to support communication between parents and registered child-minders, to provide preschool language training, and to cooperate with local family guidance offices and other family support institutions (Linder, Sprenger & Rietmann, 2008).

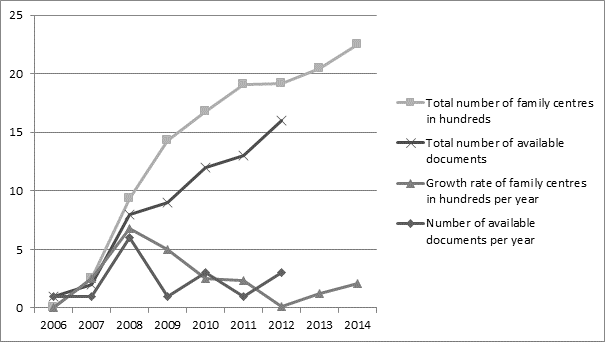

The greatest expansion occurred directly after the end of the pilot project in 2007. Growth rates remained high until 2008 (see Figure 1). Overall, about 2000 day-care institutions in North Rhine-Westphalia were changed into family centers in 2008. After 2008, growth rates started to slow, but the number of family centers still rose. The latest official statistics show that more than 3000 day-care facilities have been licensed as family centers or as elements of family centers. That accounts for approximately every third day-care institution in North Rhine-Westphalia. The state of North Rhine-Westphalia supports certified institutions to the tune of €13,000 per annum, or €14,000 if the institution is located in a low-income neighborhood.

Figure 1: Documents analysed and the expansion of family centres in the German state of North Rhine-Westphalia

These data show that there has been an extensive institutional spread of family centers in North Rhine-Westphalia. The spread is clearly driven by both the pilot project and the follow-up support program. In contrast, financial support by the state cannot explain the expansion, being relatively modest. To gain a better understanding of this institutional spread, therefore, it seems promising to analyze the political promotion documents that frame North Rhine-Westphalia’s family center program. In the following, we will explore the assumptions about families that can be found in these documents.

3 Assumptions about families in political promotion documents on family centers: Results of an exploratory document analysis

To answer our third question, how the successful launch of family centers relates to specific assumptions about families, we analyzed 16 political documents promoting family centers in North Rhine-Westphalia. Our document analysis focused on the authors’ explicit statements about families and social policy for families in Germany. Although we generally regard our document analysis as a qualitative research tool (Bowen, 2009) that filters meanings from the analyzed texts (Krippendorff, 2010, p. 233), our research approach nevertheless relates to fundamental principles of quantitative content analysis (Prior, 2008, p. 230), as we assume that the distribution and frequency of occurrence is significant for evidence (Bailey, 1978, pp. 283–284; Krippendorff, 2010, p. 234). We therefore first categorized, then counted the statements in order to determine the dominant assumptions on families and family policy throughout the documents. At 0.81, the inter-coder reliability coefficient can be considered relatively high (see Julien, 2008, p. 121).

3.1 Study sample

Our analysis is based on all the 11 relevant speeches held by representatives of the Ministry for Family Affairs in North Rhine-Westphalia between 2006 and 2012. Most of these speeches were held at openings or promotional events during the implementation period. We also analyzed the current state-level coalition agreement between the Social Democratic Party and the Greens, as well as two brochures, one flyer, and one homepage, all published by the Ministry.

The documents collected, then, were created between 2006 and 2012, but the sources are not evenly distributed over the years. Instead, the number of documents per year peaks in 2008 (see Figure 1). This coincides with a peak in the growth rate of family centers in North Rhine-Westphalia. Closer inspection shows that in the long run these data correlate only weakly (r=0.52); however, there is a strong correlation between the total number of family centers and the total number of available documents over the years (r=0.98).

Even though we dealt with a very small number of documents, we can conclude from this latter correlation that speeches and other documents promoting family centers form part of both the implementation process, and the subsequent expansion. We therefore assume that our analysis of the documents can deliver insights into political dynamics that interrelate with the institutional growth of family centers in North Rhine-Westphalia.

3.2 Description of the main findings

To uncover the assumptions about families that are embedded in the documents, we screened these for statements on families and on social policy for families, and counted the occurrences. Of 101 statements identified, 43 could clearly be assigned to three subordinate categories, representing the three main assumptions on families in Germany across the documents:

· Family life is difficult to combine with the challenges of modern working life.

· Families from ethnic minority communities are hard to reach and need extra attention and tailored social services.

· Families are crucial for children’s development and education, and are therefore a decisive factor in children’s future opportunities.

Table 2 shows how frequently and in how many separate documents we identified these three assumptions.

Table 2: Main assumptions on families in Germany to be found in the documents analysed

|

Assumption |

Total number of statements supporting the assumption |

Number of documents containing statements that support the assumption; n=16 |

|

Family is difficult to combine with the challenges of modern working life |

18 |

12 |

|

Families from ethnic minority communities are hard to reach, and need extra attention and tailored social services |

11 |

9 |

|

Families are crucial for children’s development and education, and are therefore a decisive factor in children’s future opportunities |

14 |

8 |

The first assumption, that family is difficult to combine with the challenges of modern working life, appears most often. It can be found in three quarters of all documents (see Table 2). Some statements are rather general, such as: “The institutions … must provide tailored services geared to the needs of parents and children so that family and work can be balanced and all children can receive the best opportunities for education and development” (MFKJKS, 2010; our translation, here and throughout). Other statements specify what the authors consider to be the challenges of modern working life. For example, the claim is regularly made that the modern labor market demands flexible and mobile employees, making it difficult for parents to find a stable work/life balance. It is assumed that due to their mobility and flexibility, parents are unable to count on relatives, long-time friends or neighbors to support them with their children. Further, the documents suggest that families are not easily able to make reliable plans for a regular weekly schedule. Women are seen as particularly unable to find a balance in this respect: “Employees are expected to be flexible and mobile. Women – quite rightly – do not want to have to choose between job and family” (Schäfer, 2010, p. 4, Minister for Family Affairs 2010-2015). More statements belonging to this first category can be found in various other documents (Gierden-Jülich, 2008a, 2008b; Laschet, 2006, 2007, 2008, 2009; MFKJKS, 2011, 2012; MGGFI, 2010; Schäfer, 2008, Head of the Department “Children and Youth” at the Ministry for Family Affairs 2005-2010).

The second assumption, that families from ethnic minority communities are hard to reach and need extra attention and tailored social services, distinguishes between different types of families. While the first assumption refers to families in general, this one opens up a familial subcategory. It can be found 11 times, in more than half of all documents, and is often connected to the idea that regular social services do not reach families from minority communities. For example, Laschet (2008, p. 13, Minister for Family Affairs 2005-2010) states: “So far, families with a history of immigration have had particular difficulties accessing existing family education and family guidance services.” This is seen as even more relevant because every fourth inhabitant of North Rhine-Westphalia has an immigrant background. And the percentage is even higher for children and young people. Against this background, it is important to us that family centers actively approach families with immigrant backgrounds and that they work with an intercultural focus. (Gierden-Jülich 2009a, p. 13, State Secretary in the Ministry for Family Affairs 2005-2010)

There are further documents that contain statements associated with the second assumption (Gierden-Jülich, 2008a, 2008b, 2009a, 2009b; Laschet, 2008; MFKJKS, 2010, 2011; Schäfer, 2008).

The third assumption is that families are crucial for children’s development and education and are therefore a decisive factor in their future life opportunities. We found this 14 times, in eight of the analyzed documents, for example:

Our children need the best starting conditions for a good life. We want to leave no child behind. Anyone who wants to support children early and well must also support and strengthen their parents’ ability to assume responsibility. The education of children and family education belong together when it comes to children’s quality of life and educational success. (Schäfer. 2010, p. 1)

The assumption becomes even clearer when Laschet (2007, p. 5) states: “Families fulfill indispensable duties for the personal development of the individual. And they are the nucleus of society. Family is and remains the most reliable lifestyle – that’s why the family is so important to us. In other words, the family is seen as essential both for instilling social values and behavior and for the future of society and its members’ chances of success on the labor market. The family is asserted to be the most important educational institution, the most reliable factor for shaping children’s individual development and success – and as the future of Germany as a “work society”. There are other documents that contain similar statements embodying the third assumption (Gierden-Jülich, 2008a, 2008b; Laschet, 2006; MFKJKS, 2010; Schäfer, 2008; SPD & Grüne, 2012).

Our analysis indicates that these three assumptions are the dominant ones among all assumptions about families in the documents. At the same time, they are not as politically constant as they might appear at first glance. For example, a more detailed analysis of the second assumption shows that the emphasis on families from ethnic minority communities has been fading since 2010. Since then, it has been increasingly replaced by another assumption that “families who live in underprivileged neighborhoods” are the ones who are hard to reach and need extra attention and tailored social services. The following excerpt exemplifies this assumption, which we found three times, in three of the documents:

We have to support family centers in such a way that they can serve those families who particularly need our help. It is therefore necessary to equip family centers so they are able to accomplish their tasks. This is not possible with the resources currently provided by the state of North-Rhine Westphalia, notably in underprivileged neighborhoods. A readjustment must take place. (Schäfer, 2010, p. 3)

3.3 Data interpretation

For the purposes of the following interpretation, we presuppose that definitions of social problems are key to social policy implementations (Groenemeyer, 2010), and that social problems do not exist per se, but are constituted and formed along with ideas of how to solve them through social policy (Kaufmann, 2013, p. 25). As we have shown, political documents promoting family centers in Germany generate three main assumptions about families. As a starting point for our data interpretation, we propose to regard these assumptions as essential for the political implementation of family centers in Germany. The assumptions identified make it possible to think of families as entities that are connected to social problems, which in turn makes it possible to interpret family centers as answers to those problems.

In the first assumption – family is difficult to combine with the challenges of modern working life – support for families is tied to the phenomenon of the modern labor market. Such statements thus link the support of families to German labor market policy. Statements belonging to the second assumption – families from ethnic minority communities are hard to reach and need specific services – consider family to be an important factor in the integration of ethnic minorities, and therefore tie families to immigration phenomena and policy. Statements related to the third assumption – family is crucial for the development, education and future opportunities of children – connect families to child and youth welfare policy, education policy, and labor market policy.

Overall, then, the assumptions about families that we found throughout the documents analyzed do not primarily epitomize social policies for families. Even less do they symbolize new social polities for families in Germany. Instead, the assumptions connect families to at least four fields of German social policy that were distinctly defined long before the idea of family centers was born: labor market policy, immigration policy, child and youth welfare policy, and education policy. We can conclude that, at least in the context of family centers, families themselves may actually matter less for social policy in Germany than it first appears. It is primarily the assumptions about families in the documents that are of value at this point, as it is these assumptions that enable families to be connected to the social problems traditionally addressed by German social policy. That is to say, in the framework of family centers, families in Germany do not represent a distinct “social problem” themselves, but rather are a medium to react to social problems other than family that have long since been defined by German social policy.

The fact that the focus of North Rhine-Westphalia’s family center policy increasingly changed from “immigrants” to “people from underprivileged neighborhoods” from 2010 on supports this interpretation. Precisely, the change can easily be traced back to the change of government that took place in North Rhine-Westphalia in 2010. Before that point, the Christian Democrats (CDU) governed the state in coalition with the liberal and business-oriented Free Democrats (FDP). After 2010, the Social Democrats (SPD) formed a coalition with the Greens (Bündnis 90/Die Grünen). Whereas the CDU/FDP government’s representatives stressed the needs of immigrant families, thus connecting their conservative views on immigration and cultural assimilation to the family center program, the SPD shifted that focus to families from underprivileged neighborhoods, thus linking the existing family center program to a standard social democratic agenda: social reform as part of a politics of class. This example suggests that the assumptions about families we found in the documents are a means for social policy both to generate and to flexibly modify connections between family center programs and various social policy fields.

4 Against all odds? How much of a transformation does an establishment of family centers in Germany represent?

In what follows, we like to use the results of our empirical exploration as a first hint to understand the implementation and expansion of family centers in Germany from a more historical perspective.

It has been argued that family center programs illustrate a shift in social policy, which has been internationally portrayed as a supranational move towards “remarkably piecemeal, but cumulatively robust” new strategies of “social investment” (Hemerijk, 2015, p. 242). This argument is insofar convincing to us as various studies could show that, on a programmatic level, social investment strategies prove exceptionally flexible in terms of their integration into various national social policy agendas (Morel, Palier & Palme, 2012; Schönig, 2006, p. 26), and it seems this flexibility mirrors in the case of family centers on both a programmatic and organizational level, as we could show in our afore-described empirical work on family centers in North Rhine-Westphalia.

Social investment strategies have been widely criticized for their shortcomings with respect to various national frameworks and fields (Bothfeld & Rouault, 2015; Jenson, 2012; Olk & Hübenthal, 2009). We follow another path here. It is our aim to gain a more precise knowledge of how much of a change family centers actually represent not only on a programmatic, but an institutional level.

To analyze this question, it is helpful to have a brief look at how social service provision in Germany has usually been structured, and how those structures are reflected in the assumptions about families that we identified in our document analysis on family centers in North Rhine-Westphalia. In a nutshell, there are two traditions structuring social policy in Germany, which seem important to keep in mind here.

A first tradition is that, since the 1900s, all relevant German social policy, including both social insurance and public assistance, has been legally established by Federal law (Zacher, 2013). The only exception to this rule, which is albeit of particular importance, is education policy: the German constitution makes the individual states responsible for all issues concerning public schools and universities. (Which, by the way, might be a reason for the to some extent “typically German” argument that education policy does not belong to social policy in a narrower sense) In order to significantly influence all social policy except education policy though, it is usually necessary for policy advocates and politicians to achieve a broad consensus in the national parliament and rewrite relevant sections of the German social welfare code (Sozialgesetzbuch). This legislation also regulates how social services are financed; funding of social services through the channel of individual programs, in contrast, is rare. That is to say that Germany’s family center programs are not just another social policy program in a traditionally program-driven social policy structure like the UK’s or the US’s (Garrett, 2007; Howard, 2007: 31), but represent an exception in the German context in which social policy is traditionally formed by federal law.

Secondly, as regards public assistance, social policy in Germany has been divided into various legal and administrative sectors for over a century. These sectors were shaped and established at the turn of the nineteenth to the twentieth century, and since then have developed in parallel thanks to relatively separate legislation (different sections of the federal social welfare code) and administration (different public offices being responsible for the various services). There are mainly four of these sectors of public assistance: services legally and administratively directed at labor market integration; child and youth welfare services; general assistance and basic income services; and health care services – but there is no distinct sector for “family services.”

The spread of family centers, then, appears to have occurred against the grain of social policy development so far, at least as far as its two aforementioned basic traditions go. To at least sketch a possible answer to the question of how family centers could nevertheless take root in Germany, we draw on two broader theoretical approaches that combine well (Hasse & Krücken, 2009, p. 248). On the one hand, we refer to some basic elements of Niklas Luhmann’s theory of social systems (Luhmann, 1995, 2013) to explain how German social policy uses family center programs to respond to environmental stimuli. On the other, we concretize the institutional legitimization of family centers as organizations with the help of some concepts from new institutionalism (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983; Deephouse & Suchman 2008).

In Luhmann’s theory of social systems, modern societies represent a heterarchy of relatively independent, self-referential, subsystemic circles of communication – such as politics, economy, media, and so on (Luhmann, 1995, p. xxxv). These, in fact, are what Luhmann calls “social systems”. To stay “alive”, social systems need to constantly refer to their environment, but such reference is made in a very selective and self-referential way. Social systems thus diversify their inner communication by means of highly selective references to environmental communicative stimuli, which they can use to perpetuate their own communication. This very active form of reference and variation makes it possible for a social system to remain dynamically stable without being directly influenced or even determined by its environment. Given this, it would be misleading to represent societal change as something that can be steered, or even only intentionally triggered, by any single social system. As a result, from a perspective of Luhmann’s theory of social systems, neither is a narrative of an “economization of the social” convincing (Stäheli, 2011, p. 272), nor can politics purposively change society using policy agendas and their implementations (King & Thornhill, 2003). Instead, societal change must always make sense from various subsystemic perspectives (Willke, 1989). The same is also assumed to be true within the subsystems of social systems themselves. One such subsystem would be social policy.

If we apply these basic concepts from Luhmann’s theory of social systems to our research object, it emerges that while the social investment approach is a worthwhile category of description for what is going on in Germany’s political system in terms of agendas, social policy cannot entirely be understood as something that is politically determined from the top down. In Germany, both the discursive reality of social politics and the organizational reality of the social polity (Hajer, 2003) have produced certain structures that mark out a self-referential subsystem of social policy communication. Social policy in Germany, as a subsystem of society, can only change gradually and heterarchically within the pre-existing communicative structures it has generated, and with reference to pre-existing communicative elements from the system’s environment, which can be varied by the system in new ways. In turn, this means that cumulative references to “family” might diversify, but are unlikely to change the functioning of social policy in Germany substantially over the course of a changed agenda.

To concretize these thoughts with regard to what we found out on the institutional establishment of family centers in Germany’s state of North Rhine-Westphalia, we suggest viewing this process as a programmatic reaction by German social policy to the increasingly fierce debates on families and on the need for a distinct family policy (Ferragina, Seeleib-Kaiser & Tomlinson, 2013; Klammer & Letablier, 2007), but as one that has had to take the pre-existing legal and organizational structures of social services as a starting point for communication since these structures are the most relevant environment of family centers in Germany (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983). This means in return that these pre-existing legal and organizational structures tend to “suck in” the “new” social policy agenda of family centers as “family services” and reverse it with regard to the given four-tier structure of German social policy sectors that we outlined above.

Precisely, our document analysis on the case of North Rhine-Westphalia’s family centers shows that even in political promotion, the centers had not only to be organizationally connected to day-care facilities, but were also communicatively connected to three of the four, long-established sectors of public assistance: child and youth welfare services, general assistance and basic income services, and services officially aiming for labor market integration. Put another way, it seemed necessary to communicatively connect North Rhine-Westphalia’s family center program to these three traditional sectors of Federal German social policy in order to institutionally legitimize the program as a worthwhile part of public assistance in Germany (Deephouse & Suchman, 2008). Over the course of these connections, it then became possible to promote and organize family centers as something that would be understood as a social service organization in its “German” sense.

For conclusion, we can hypothesize that for family centers to take root in Germany at large, communicative connections with more long-established sectors of public assistance are, paradoxically, both necessary and restrictive. On the one hand, they seem necessary for any institutionalization of family centers in Germany; on the other, they might tie family centers down to the systemic logics of traditional social services in Germany, which continue to focus on social problems clearly going beyond families.

References

Bailey, K. D. (1978). Methods of social research. New York: Free Press.

Bauder, H., Lenard, P. T., & Straehle, C. (2014). Lessons from Canada and Germany: Immigration and Integration Experiences Compared – Introduction to the Special Issue. Comparative Migration Studies, 2(1), 1-7.

Bothfeld, S. & Rouault, S. (2015). Families facing the crisis: Is social investment a sustainable social policy strategy? Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State & Society, 22 (1), 60–85.

Bowen, G. A. (2009). Document analysis as a qualitative research method. Qualitative Research Journal, 9(2), 27–40.

Bundesministerium für Familien, Senioren, Frauen und Jugend (BMFSFJ) (2006). Seventh family report: Families between flexibility and dependability – Perspectives for a life cycle-related family policy. Statement by the Federal Government. Berlin: BMFSFJ.

Deephouse, D. L., & Suchman, M. (2008). Legitimacy in organizational institutionalism. In R. Greenwood, C. Oliver, R. Suddaby & K. Sahlin-Andersson (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of organizational institutionalism (pp. 49–77). London: SAGE.

Diller, A. (2010). Familenzentren und Co: Veränderte Organizationsformen und ihr Beitrag zur Veränderung des Verhältnisses von familialer und öffentlicher Erziehung [Family Centers and Co: Changing Organizations und their influence on the relationship of public and private education and care]. In P. Cloos & B. Karner (Eds.), Erziehung und Bildung von Kindern als gemeinsames Projekt (pp. 137–152). Baltmannsweiler: Schneider.

Diller, A., & Schelle, R. (2009). Von der Kita zum Familienzentrum: Konzepte Entwickeln – erfolgreich umsetzen [From Day-care Center to Family Center: Development of Concepts – Successful Conversion]. Freiburg: Herder.

DiMaggio, P., & Powell, W. (1983). The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review, 48 (2), 147–160.

Esping-Andersen, G. (1990). The three worlds of welfare capitalism. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Eurochild (2012). Compendium of inspiring practices – Early intervention and prevention in family and parenting support. http://www.eurochild.org/fileadmin/Communications/09_Policy%20Papers/policy%20positions/EurochildCompendiumFPS.pdf. (Accessed 28 April 2014)

Ferragina, E., Seeleib-Kaiser, M., & Tomlinson, M. (2013). Unemployment protection and family policy at the turn of the 21st century: A dynamic approach to welfare regime theory. Social Policy & Administration, 47 (7), 783–805.

Garrett, P. M. (2007). “Sinbin” solutions: The “pioneer” projects for “problem families” and the forgetfulness of social policy research. Critical Social Policy, 27 (2), 203–230.

Gierden-Jülich, M. (2008a). Von der Kindertageseinrichtung zum Familienzentrum: Die 500 neuen Familienzentren im Kindergartenjahr 2008/2009 [From Day-care Institutions to Family Centers: The new 500 Family Centers in term of 2008/09]. http://www.familienzentrum.nrw.de/tagungsdokumentation.html. (Accessed 17 May 2013)

Gierden-Jülich, M. (2008b). Von der Kindertageseinrichtung zum Familienzentrum: Die 500 neuen Familienzentren im Kindergartenjahr 2008/2009 [From Day-care Institutions to Family Centers: The new 500 Family Centers in term of 2008/09]. http://www.familienzentrum.nrw.de/tagungsdokumentation.html. (Accessed 17 May 2013)

Gierden-Jülich, M. (2009a). Von der Kindertageseinrichtung zum Familienzentrum: Die 500 neuen Familienzentren im Kindergartenjahr 2008/2009. [From Day-care Institutions to Family Centers: The new 500 Family Centers in term of 2008/09] http://www.familienzentrum.nrw.de/tagungsdokumentation.html. (Accessed 17 May 2013)

Gierden-Jülich, M. (2009b). Von der Kindertageseinrichtung zum Familienzentrum: Die 500 neuen Familienzentren im Kindergartenjahr 2008/2009 [From Day-care Institutions to Family Centers: The new 500 Family Centers in term of 2008/09]. http://www.familienzentrum.nrw.de/tagungsdokumentation.html. (Accessed 17 May 2013)

Gillies, V. (2005). Meeting parents’ needs? Discourses of “support”and “inclusion” in family policy. Critical Social Policy, 25 (1), 70–90.

Groenemeyer, A. (2010). Doing Social Problems – Doing Social Control: Mikroanalysen der Konstruktion sozialer Probleme in institutionellen Kontexten – Ein Forschungsprogramm [Doing Social Problems – Doing Social Control: Microanalyses of the construction of social Problems in institutional settings – A Research Program]. In A. Groenemeyer (Ed.), Doing Social Problems: Mikroanalysen der Konstruktion sozialer Probleme und sozialer Kontrolle in institutionellen Kontexten (pp. 13–56). Wiesbaden: VS.

Hajer, M. (2003). Policy without polity? Policy analysis and the institutional void. Policy Sciences, 36 (2), 175–195.

Hasse, R., & Krücken, G. (2009). Neo-institutionalistische Theorie [Theory of Neo-institutionalism]. In G. Kneer & M. Schroer (Eds.), Handbuch Soziologische Theorien (pp. 237–251). Wiesbaden: VS.

Hemerijck, A. (2015). The quiet paradigm revolution of social investment. Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State & Society, 22 (2), 242–256.

Howard, C. (2007). The welfare state nobody knows: Debunking myths about US social policy. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press.

Jenson, J. (2012). Redesigning citizenship regimes after neoliberalism: Moving towards social investment. In N. Morel, B. Palier, & J. Palme (Eds.), Towards a social investment welfare state? Ideas, policies and challenges (pp. 61–87). Bristol: Policy Press.

Jüttner, A.-K. (2010). Investitionen in Kinder: Familienzentren und Children’s Centers im Vergleich [Investing in Children: Comparing Family Centers ans Children´s Centers]. Sozialer Fortschritt, 59 (4), 103–107.

Julien, H. (2008). Content analysis. In L. M. Given (Ed.), The SAGE encyclopedia of qualitative research methods, vol. 1 (pp. 120–122). Los Angeles: SAGE.

Kaufmann, F.-X. (2013). Variations of the welfare state: Great Britain, Sweden, France and Germany between capitalism and socialism. Berlin: Springer.

King, M., & Thornhill, C. J. (2003). Niklas Luhmann’s theory of politics and law. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Klammer, U., & Letablier, M. T. (2007). Family policies in Germany and France: The role of enterprises and social partners. Social Policy & Administration, 41 (6), 672–692.

Krippendorff, K. (2010). Content analysis. In N. J. Salkind (Ed.), Encyclopedia of research design, vol. 1 (pp. 233–238). Los Angeles: SAGE.

Laschet, A. (2006). Familienzentrum NRW. Was ist erreicht, was bleibt zu tun? [Family Centers, what has been accomplished, what remains to be done?] http://www.familienzentrum.nrw.de/tagungsdokumentation.html. (Accessed 17 May 2013)

Laschet, A. (2007). Ein wichtiges Ziel ist erreicht [An Important Goal is reached]. http://www.familienzentrum.nrw.de/tagungsdokumentation.html. (Accessed 17 May 2013)

Laschet, A. (2008). Von der Kindertageseinrichtungen zum Familienzentrum: Die 500 neuen Familienzentren im Kindergartenjahr 2008/2009 [From Day-care Institutions to Family Centers: The new 500 Family Centers in term of 2008/09]. http://www.familienzentrum.nrw.de/tagungsdokumentation.html. (Accessed 17 May 2013)

Laschet, A. (2009). Familienzentren in Nordrhein-Westfalen – neue Zukunftsperspektiven für Kinder und Eltern [Family Centers in North Rhine-Westphalia- new perspectives for Children and Parents]. http://www.familienzentrum.nrw.de/tagungsdokumentation.html. (Accessed 17 May 2013)

Linder, E. J., Sprenger, K., & Rietmann, S. (2008). Familienzentren in Nordrhein-Westfalen: Ein Überblick über die Pilotphase [Family Centers in North Rhine-Westphalia: a survey of the Pilot Phase]. In S. Rietmann & G. Hensen (Eds.), Tagesbetreuung im Wandel: Das Familienzentrum als Zukunftsmodell (pp. 277–291). Wiesbaden: VS.

Luhmann, N. (1995). Social systems. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Luhmann, N. (2013). Theory of society. 2 vols. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Martin, P. L. (2004). Germany: Managing migration in the twenty-first century. In W. A. Cornelius, T. Tsuda, P. L. Martin & J. F. Hollifield (Eds.), Controlling immigration: A global perspective, 2nd ed. (pp. 221–253). Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Meyer-Ullrich, G., Schilling, G., & Stöbe-Blossey, S. (2008). Der Weg zum Familienzentrum – Eine Zwischenbilanz der wissenschaftlichen Begleitung [The Path to Family Centers- interim results of the scientific monitoring]. Berlin: päd.quis.

Ministerium für Familie, Kinder, Jugend, Kultur und Sport des Landes Nordrhein-Westfalen (MFKJKS) (2010). Hilfen aus einer Hand: Familienzentren in Nordrhein-Westfalen [One-stop Social Services: Family Centers in North Rhine- Westphalia]. Düsseldorf: MFKJKS.

MFKJKS (2011). Gütesiegel Familienzentrum Nordrhein-Westfalen Westfalen [Seal of Quality Family Center North Rhine-Westphalia]. Düsseldorf: MFKJKS.

MFKJKS (2012). Familienzentren NRW Hompage [Family Centers North Rhine-Westphalia]. http://www.familienzentrum.nrw.de/landesprojekt.html. (Accessed 17 May 2013)

Ministerium für Generationen, Familie, Frauen und Integration des Landes Nordrhein-Westfalen (MGFFI) (2007). Das Gütesiegel Familienzentrum NRW. Zertifizierung der Piloteinrichtungen [The seal of quality family center in North Rhine-Westphalia. Certification of the pilot institutions]. Düsseldorf: MGFFI.

MGFFI (2008). Wege zum Familienzentrum Nordrhein-Westfalen: Eine Handreichung Handreichung [Ways to become a Family Center in North Rhine-Westphalia: a guidance]. http://www.familienzentrum.nrw.de/fileadmin/documents/pdf/handreichung.pdf. (Accessed 17 May 2013)

MGFFI (2010). Familienzentren in Nordrhein-Westfalen: Ein neuer Weg der Förderung von Kindern und Familien [Family centers in North Rhine-Westphalia: A New Way of Supporting Children and Families]. Düsseldorf: MGFFI.

Morel, N., Palier, B., & Palme, J. (2012). Beyond the welfare state as we knew it? In N. Morel, B. Palier & J. Palme (Eds.), Towards a social investment welfare state? Ideas, policies and challenges (pp. 1–30). Bristol: Policy Press.

Müncher, V., & Andresen, S. (2009). Bedarfsorientierung in Familienzentren – Eltern als neue Adressaten [Need-Orientation in Family Centers – Parents as new addressees]. In C. Beckmann, H. U. Otto, M. Richter, & M. Schrödter (Eds.), Neue Familialität als Herausforderung der Jugendhilfe (pp. 108–118). Lahnstein: Neue Praxis.

Oberhuemer, P., Schreyer, I., & Neuman, M. J. (2010). Professionals in early childhood education and care systems: European profiles and perspectives. Opladen: Barbara Budrich.

Olk, T., & Hübenthal, M. (2009). Child poverty in the German social investment state. Zeitschrift für Familienforschung, 21 (2), 150–167.

Prior, L. F. (2008). Document analysis. In L. M. Given (Ed.), The SAGE encyclopedia of qualitative research methods, vol. 1 (pp. 230–232). Los Angeles: SAGE.

Rietmann, S. (2008). Das interdisziplinäre Paradigma. Fachübergreifende Zusammenarbeit als Zukunftsmodell [The Interdisciplinary Paradigm. Interdisciplinarity as Model for the Future]. In S. Rietmann & G. Hensen (Eds.), Tagesbetreuung im Wandel: Das Familienzentrum als Zukunftsmodell (pp. 39–58). Wiesbaden: VS.

Rietmann, S., & Hensen, G. (2008). Einleitung [Introduction]. In S. Rietmann & G. Hensen (Eds.), Tagesbetreuung im Wandel: Das Familienzentrum als Zukunftsmodell (pp. 9–12).Wiesbaden: VS.

Schäfer, K. (2008). Von der Kindertageseinrichtungen zum Familienzentrum: Die 500 neuen Familienzentren im Kindergartenjahr 2008/09 [From Day-care Institutions to Family Centers: The new 500 Family Centers in term of 2008/09]. http://www.familienzentrum.nrw.de/tagungsdokumentation.html. (Accessed 17 May 2013)

Schäfer, U. (2010). Von der Kindertageseinrichtung zum Familienzentrum [From Day-care Institutions to Family Centers]. http://www.mfkjks.nrw.de/presse/reden/. (Accessed 4 June 2013)

Schönig, W. (2006). Aktivierungspolitik. Eine sozialpolitische Strategie und ihre Ambivalenz für soziale Dienste und praxisorientierte Forschung [Activation Policy. A social policy strategy and ist ambivalence]. In B. Dollinger & J. Raithel (Eds.), Aktivierende Sozialpädagogik. Ein kritisches Glossar (pp. 23–39). Wiesbaden: VS.

Schlevogt, V. (2012). KiFaz, Eltern-Kind-Zentrum oder Haus der Familie: Konzepte und Fördermodelle von Kinder- und Familienzentren im bundesweiten Vergleich [Children and family Centers, Parents-Children-Centers or House of the Family: Concepts and support programs a nationwide comparison]. KiTa aktuell, 20 (1), 6–8.

Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands (SPD) and Grüne (2012). Koalitionsvertrag 2012–2017 [Coalition Agreement 2012-2017]. http://nrwspd.de/db/docs/doc_40518_2012121111516.pdf. (Accessed 5 June 2013)

Stäheli, U. (2011). Decentering the economy: Governmentality studies and beyond. In U. Bröckling, S. Krasmann & T. Lemke (Eds.), Governmentality: Current issues and future challenges (pp. 269–284). New York: Routledge.

Statistisches Bundesamt (2014a). Bevölkerung und Erwerbstätigkeit [Population and Employment]. Wanderungen. Wiesbaden: Statistisches Bundesamt.

Statistisches Bundesamt (2014b). Familien mit minderjährigen Kindern nach Familienform [Families with Minor Children according to Family Forms]. www.destatis.de/DE/ZahlenFakten/GesellschaftStaat/Bevoelkerung/HaushalteFamilien/Tabellen/Familienformen.html. (Accessed 8 December 2014)

Stoy, V. (2014). Worlds of welfare services: From discovery to exploration. Social Policy & Administration, 48 (3), 343–360.

Textor, M. R. (2008). Vernetzung von Kindertageseinrichtungen mit psychosozialen Diensten [Integration of Day-care Institutions and Psychosocial Services]. In S. Rietmann & G. Hensen (Eds.), Tagesbetreuung im Wandel: Das Familienzentrum als Zukunftsmodell (pp. 121–132). Wiesbaden: VS.

Willke, H. (1989). Zum Problem staatlicher Steuerung im Bereich der Sozialpolitik [The Problem of State Control in the Field of Social Policy]. In G. Vobruba (Ed.), Der wirtschaftliche Wert der Sozialpolitik (pp. 109–120). Berlin: Duncker & Humblot.

Zacher, H. F. (2013). Social policy in the Federal Republic of Germany: The constitution of the social. Berlin: Springer.

Authors Address:

Onno Husen

Leuphana University Lüneburg

Universitätsallee 1

21335 Lüneburg, Germany

husen@leuphana.de

Authors Address:

Philipp Sandermann

Leuphana University Lüneburg

Universitätsallee 1

21335 Lüneburg, Germany

sandermann@leuphana.de