Ranking Work-Family Policies across OECD Countries: Implications for Work-Family Conflict, Gender Equality, and Child Well-being

I-Hsuan Lin, Indiana University School of Social Work, Indianapolis

1 Introduction

Facing dramatically changed demographic trends and harsher working conditions due to economic globalization, working parents across countries perceive increased work-family conflict[1] (Hassan, Dollard, & Winefield, 2010; Kaufman, 2013; Kelly, Moen, & Tranby, 2011; Moe & Shandy, 2010; Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2007, 2013b; Rapoport, Bailyn, Fletcher, & Pruitt, 2002; Sweet, 2014). Work-family conflict has “dysfunctional and socially costly effects on individual work life, home life, and general well-being and health” (Allen, Herst, Bruck, & Sutton, 2000, p. 301). It also negatively affects the well-being of organizations and society as a whole, in terms of productivity and gender equality (Cha, 2010; Meurs, Breaux, & Perrewé, 2008). Work-family conflict may negatively affect children’s well-being as well through lower quality parenting behaviour, higher family stress, less family satisfaction, and so forth (Allen et al., 2000; Amstad, Meier, Fasel, Elfering, & Semmer, 2011; Cooklin et al., 2015).

Work-family policies have been developed to help working parents address work-family conflict. It is not only an effort made by a single country, but an effort adopted by the international community. For decades, the European Union (EU) has been concerned with work-family conflict and gender equality. EU has strived for promoting the reconciliation of work and family life and increasing female labour force participation through directives and work-family policies (Chandra, 2012; Haas, 2003; Moss & Deven, 2006; Naumann, McLean, Koslowski, Tisdall, & Lloyd, 2013). Similarly, other international organizations, such as the International Labour Organisation (ILO), the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the United Nations (UN), and the World Bank, are also concerned with these issues (Adema, 2012; Moss & Deven, 2006; Naumann et al., 2013; Whitehead, 2008). Internationally, the most common work-family policies that are implemented to help employees reconcile work and family demands include leave policies (i.e., maternity leave, paternity leave, and parental leave), early childhood education and care policy (ECEC), out-of-school-hours care services, flexibility policies (e.g., breastfeeding break, flexibility in deciding when to start and finish daily work, reduced working hours, part-time work, condensed work weeks, etc.), and tax policy (Blau, Ferber, & Winkler, 2014; Gornick & Meyers, 2003; Kaufman, 2013; Moss & Deven, 2006; OECD, 2007, 2014m).

Although various work-family policies have been developed to help working parents reconcile work and family obligations, the supportiveness level of policies varies across countries, which not only differentiates whether countries help working parents address work-family conflict, but also reflects assumptions underlying policies that either reinforce or address gender inequality. Furthermore, since work-family conflict and related gender inequality have a negative impact on child well-being, work-family policies as interventions are also likely to influence child outcomes. Research has found that policies that support working parents by giving them time to be with their children while securing their jobs and income or that provide affordable, good quality child care when parents are at work can not only address work-family conflict and gender inequality but also maintain or even increase children’s well-being. Three types of policies that can have such effects and are consistently recommended by researchers are job-protected paid leave, flexible work arrangements, and publicly subsidized good quality child care (Berger, Hill, & Waldfogel, 2005; Brooks-Gunn, Han, & Waldfogel, 2010; Engster & Stensöta, 2011; Ruhm, 2000, 2004).

This current research examines how work-family policies are designed across OECD countries in terms of the generosity and the coordination among parental leave, ECEC and flexible work arrangement policies, and gender equality measures in policy schemes. Countries are scored and ranked based on their policy designs. A new typology of four policy regimes is further constructed based on a care-employment analytic framework that assesses how countries regard parents’ dual roles of workers and caregivers, whether and how countries compensate caregiving, how childcare responsibility is distributed among the state, market, and family and between men and women within families, as well as gender gaps in employment outcomes. This new set of regime types represents countries’ varied abilities to help parents reconcile work and family demands. This comparative analysis not only allows for a better understanding of the link between policy regimes and daily lives (Zimmerman, 2013) but also provides available and accessible information for parents and social workers to advocate for more statutory support to address work-family conflict while promoting gender equality and child well-being.

1.1 Previous efforts to compare and typologize work-family policies and gaps

Work-family conflict is the product of the tension between employment and caregiving, as it is a result of incompatible, competing demands from paid work and unpaid care work caused by dated but embedded assumptions of separate spheres of work and family, gendered division of labour, and an ideal worker norm in workplaces and social policies (J. Lewis, 1992, 1997; Rapoport et al., 2002). Consequently, work-family conflict is gendered and has implications for gender equality. To understand how well countries address work-family conflict and related gender inequality, it is essential to uncover underlying logic in policies about paid work and unpaid care work.

Feminist scholars began to examine the tension between employment and caregiving in the 1980s and 1990s, when they started incorporating gender into welfare state research. Since then, comparative analyses of work-family policies have proliferated to explicitly examine the role of unpaid caregiving in citizens’ daily lives and the relationship among unpaid caregiving, paid work, and welfare (Bambra, 2007; Beneria, 2010; Bolzendahl & Olafsdottir, 2008; Castles & Mitchell, 1992; Daly & Lewis, 2000; Gornick & Meyers, 2003, 2004; Haas, 2003; Knijn & Kremer, 1997; Korpi, 2000; Leira, 1998; J. Lewis, 1992, 1997; Lokteff & Piercy, 2012; Moss, 2012; Moss & Deven, 2006; Ray, Gornick, & Schmitt, 2010). A body of research has focused on comparing the generosity of parental leave designs indicated by both benefit levels and benefit duration across countries (e.g., Gornick & Meyers, 2003, 2004; Haas, 2003; Ray et al., 2010). Some researchers further explored the extent to which parental leave designs are gender egalitarian by implementing measures in policies (e.g., non-transferable leave entitlement and other incentives for men to take leave) that address a gendered division of labour in unpaid care work (e.g., Ray et al., 2010). This comparative research on parental leave has overall revealed a consistent finding that among high-income industrialized countries, Nordic countries, especially Sweden, have provided more generous and gender egalitarian leave policies. These studies have increased understanding of varied leave policy designs across nations and their implications for gendered division of labour in unpaid caregiving and women’s disadvantage in paid work. But, the vast majority of these studies compared only two dimensions of policy schemes— benefit levels and duration — without consideration of eligibility requirements and flexibility in the use of leave in policy rules that would affect the coverage of policy and parents’ actual use of leave (Boushey, 2011; Ray et al., 2010; Ruhm, 2011).

Efforts have also been taken to re-examine welfare states by researching gender and care dimensions of welfare regimes through reviewing and comparing work-family policies. In so doing, some scholars (e.g., Daly & Lewis, 2000; Haas, 2003; J. Lewis, 1992) have created new typologies of welfare regimes that are different from the one developed by Esping-Andersen (1990). For instance, Lewis (1992) identified three types of welfare regimes, including strong male-breadwinner states, modified male-breadwinner states, and weak male-breadwinner states, by analysing the relationship among unpaid care work, paid work, and welfare in Ireland, Britain, France, and Sweden. Haas (2003) also developed a typology of care policy models consisting of four care models (i.e., privatized, self-centred, market-oriented, and valued care models) based on comparative analyses of 15 EU countries’ leave policy. Many of these studies (e.g., Daly & Lewis, 2000; Haas, 2003; J. Lewis, 1992), however, have not introduced the methodology they used in their studies or developed their typologies theoretically rather than empirically, as criticized by Bambra (2007). Additionally, some of them focused on a single type of work-family policy, that is, leave policy (Haas, 2003; Moss & Deven, 2006). Although leave policy is an important measure that can help parents reconcile paid work and unpaid family obligations, this type of policy alone is insufficient to address caring needs and work-family conflict. Also, a single policy alone cannot sufficiently represent countries’ institutional responses to the tension arising from the interface between work and family. The validity of regime typologies developed based on the analysis of only one type of policy would be compromised as well. Without taking into account other types of work-family policies and the coordination level between them and leave policy, these studies could not fully assess welfare states’ efforts to provide a coordinated policy system that allows parents more leeway to choose preferred methods (e.g., taking leave or using public child care) to reconcile caregiving and employment demands.

On the other hand, other researchers have expanded their analyses to include other types of policies, such as ECEC, working time regulations, etc. (Daly & Lewis, 2000; Gornick & Meyers, 2003, 2004; Knijn & Kremer, 1997; Leira, 1998; J. Lewis, 1992). But much of this research did not systematically assess or quantify the coordination level among policies, studied only a small number of countries, and did not develop new regime typologies (Bambra, 2007; Castles & Mitchell, 1992; Gálvez-Muñoz, Rodríguez-Modroño, & Domínguez-Serrano, 2011; Gornick & Meyers, 2003, 2004; Knijn & Kremer, 1997; Korpi, 2000; Leira, 1998; Moss & Deven, 2006). Many of them used Esping-Andersen’s (1990) typology as the framework to examine leave policy, ECEC, and working time policies in particular countries from the same welfare regime (e.g., Leira, 1998) or compare these policies across few selected countries of the Social Democratic regime, Conservative regime, and Liberal regime (e.g., Gornick & Meyers, 2003, 2004; Knijn & Kremer, 1997). They found that Social Democratic countries are more likely to have generous policies to support parents’ dual roles of caregivers and workers, while Conservative and Liberal countries are substantially lagging (Gornick & Meyers, 2003, 2004; Knijn & Kremer, 1997). Although the findings of this line of research are generally in accordance with those of the aforementioned studies of Daly and Lewis (2000), Haas (2003), and Lewis (1992) concerning Social Democratic/Scandinavian countries, the findings of this line of research regarding other countries are different from those of the latter. Alternative typologies, especially the one developed by Haas (2003), further differentiated countries of the Conservative and Liberal welfare regime types constructed by Esping-Andersen (1990), by taking into account gender and unpaid care work that were overlooked in Esping-Andersen’s research (O’Connor, 1993, 1996; Orloff, 1993; Ray et al., 2010).

The welfare regime studies of work-family policies have offered new understandings of how countries can be categorized differently based on their varied work-family policy designs, which not only reflect their distinct assumptions about paid work, unpaid care work, gender relations and the state’s role in providing care that either address or reinforce gender inequality, but also differentiate countries’ abilities to reconcile parents’ competing demands of unpaid caregiving and paid work. These studies have not only established the concept that caring is an important social and policy dimension that needs to be examined in comparative policy studies, but also developed the earner-carer model (see Fraser, 1994; Gornick & Meyers, 2003; Ray et al., 2010) that recognizes and values men’s and women’s engagement in both paid work and unpaid caregiving. Researchers have envisioned that a society that views both employment and caregiving as social rights (Knijn & Kremer, 1997; Leira, 1998; J. Lewis, 1997) and that supports and encourages men and women to be both the earners and carers through policies would be the society that can better address work-family conflict while promoting gender equality. Previous studies have given valuable insights into the topic, but their limitations (e.g., overlooking eligibility and flexible use rules in leave policy, developing new welfare regime typologies based only on a single type of policy, focusing on few countries, lacking a clear methodology, relying on a typology that fails to capture gender and caring dimensions, etc.) leave substantial gaps in the comparative literature on work-family policies and regime typology. Also, very little research has discussed welfare regimes’ implications for children’s well-being. This current research attempts to fill these gaps.

1.2 The current research

This research adopts a policy regime perspective to map the governing arrangements (May & Jochim, 2012) for reconciling parents’ work and family obligations and promoting gender equality across OECD countries. Through describing policy values, ideas, principles, and institutional arrangements manifested in public actions and policy designs, a policy regime perspective provides a useful way to conceptualize distinct typologies to classify empirical similarities and differences among countries (Lange & Meadwell, 1991, as cited in Ebbinghaus, 2012; Kaufmann, 2006; May & Jochim, 2012; Pfau-Effinger, 2005). In other words, a regime typology approach is a way of backward mapping the governing arrangements that characterize the whole system by examining components of welfare provisions, such as policy designs, outcomes, etc., as suggested by literature (Arts & Gelissen, 2002; Castles & Mitchell, 1992; Ebbinghaus, 2012; Esping-Andersen, 1990; Guo & Gilbert, 2007; May & Jochim, 2012). Accordingly, this research compares two components of welfare states, that is policy designs and parents’ caregiving and employment patterns (i.e., outcomes) that can be empirically and theoretically viewed as a reflection of countries’ policy schemes and ideologies about gender roles and the roles of the state, market, and family in providing care. Specifically, countries’ policy designs are measured and compared by two indices developed in this research, while parents’ caregiving and employment patterns are captured by indicators retrieved from the OECD family database and then results are theoretically interpreted by the Care-Employment Analytic Framework formed in this research.

In agreement with Fraser (1994) and Gornick and Meyers (2004), this research assumes the equal importance of caregiving and employment in a citizen[2]’s life and argues that a desirable welfare regime should pursue inclusive citizenship by recognizing the citizens’ right to time to give care and the right to receive care in an ungendered way that emphasizes the simultaneousness of being a citizen-worker and citizen-caregiver, as suggested by Knijn and Kremer (1997). Accordingly, the Care-Employment Analytic Framework informed by the earner-carer model examines the extent to which countries move toward inclusive citizenship through assessing and comparing how countries do in helping parents care for their children without sacrificing their (especially mothers’) employment through the provisions of leave, ECEC, and flexible work arrangement policies. Specifically, this analytic framework consists of the care and employment dimension. The care dimension adopts the ideas of Daly and Lewis (2000), Knijn and Kremer (1997), and Lewis (1997) to examine the caring elements of a policy regime by investigating whether caregiving is seen as a public or private responsibility, whether caregiving is paid, whether caregiving is viewed as the rights of caregivers and care receivers, whether parents are given the right to make an autonomous choice about using or not using non-parental, formal childcare, and how care responsibility is distributed among state, market and family as well as between men and women. The employment dimension examines whether caregiving contributes to financial dependence of caregivers (especially mothers) through interrupting and repressing their employment participation (Zimmerman, 2013).

Building on the literature, this research contributes to the field by filling the aforementioned gaps. First of all, this research includes eligibility and flexibility of leave policy into analyses and compares not only the generosity of three types of work-family policies, but also the coordination level among them across a larger set of countries. Secondly, the current research incorporates a gender dimension by examining gender equality measures in policy designs and how well countries value and support parents’ dual roles of workers and caregivers. Thirdly, this research compares policies more precisely by systematically quantifying their level of generosity and coordination as well as the extent to which policies are designed to promote gender equality, using indices developed for this research. Fourthly, this research develops a new set of regime types that highlights countries’ similarities and differences in policy designs and empirical patterns of using ECEC services and informal care, gendered employment outcomes, and fathers’ use of leave. Through this systematic and empirical comparison of countries’ policy designs and outcomes, the current research identifies directions for further improvement in order to better address work-family conflict, promote gender equality, and enhance child well-being.

2 Methods

2.1 Countries of comparison, policies, procedure, and sources of data

This research is a cross-sectional comparative policy study that compared work-family policies that are applicable as of 2014 across OECD countries (n=33; Chile and Latvia were excluded due to unavailability of most data). Specifically, statutory parental leave policy[3], ECEC[4], and flexibility policy[5] were reviewed.

A multi-stage approach was employed to conduct this research. A database containing rules of parental leave policy, ECEC, and flexibility policy in OECD countries was first created for further analysis. Then, two Indices were developed to rank policy designs across countries in terms of their supportiveness level and effort level of promoting gender equality. Finally, the Care-Employment Analytic Framework was constructed for further comparison and to identify a typology of work-family policy regimes. Due to limited space, summaries of OECD countries’ policies are not reported in this article but available upon request.

Data used in this research, including the policy data, were from various sources, including the OECD databases (e.g., family, employment, and income distribution databases), government official websites, country notes published by the International Network on Leave Policies and Research, OECD and government reports, and peer-reviewed journal articles.

2.2 Measures

Supportiveness Index (SI)

The SI measures the level of generosity and comprehensiveness of work-family policies in terms of the provisions of parental leave policies and the coordination with ECEC and flexibility policies. The Supportiveness Index is composed of six indicators, including eligibility, length of leave, payment, flexible use of parental leave, ECEC coordination, and flexible work coordination. Each indicator was measured on a 5-point scale presented in Table 1. A higher value represents a higher level of each indicator, except for eligibility. Specifically, eligibility is the requirement that a working parent needs to meet to be eligible for taking parental leave. The requirements may include resident status, employment status, insurance status, working hours, one year of continual employment, company size, etc. The fewer requirements stipulated for eligibility, the greater the number of parents covered by the policy, i.e., a more supportive policy (Boushey, 2011; Ruhm, 2011). Hence, this indicator was coded reversely: countries having fewer eligibility requirements were given a higher value. For instance, countries (e.g., Finland, Sweden, Slovak Republic, etc.) that have universal entitlement (i.e., all employees or all residents are eligible) were scored as 4, while countries (none in this research) that have four or more requirements for eligibility would be scored as 1. But countries (i.e., Mexico, Switzerland, and Turkey) that do not have statutory parental leave were scored as 0.

Length of leave indicates how long an eligible parent can take time off work to care for a child. Empirically, countries’ length of leave can be categorized into the following groups: no leave granted (i.e., Mexico, Switzerland, and Turkey; scored as 0), 3 months or less (i.e., Iceland and the United States; scored as 1), 4 to 12 months (e.g., Australia, Belgium, Canada, Finland, Greece, Ireland, etc.; scored as 2), 13 to 24 months (i.e., Austria, Denmark, South Korea, and Sweden; scored as 3), and more than 24 months (i.e., Czech Republic, Estonia, France, Germany, Hungary, Poland, Slovak Republic, and Spain; scored as 4). Generally, granting 4 to 12 months of leave becomes a common practice among countries. Hence, countries falling into this category were given a score of 2 as a midpoint, while countries granting less or more than this length were scored toward two polar opposites on the scale.

Payment is the compensation for the time parents take to care for children and was assessed based on whether the entire leave duration is paid and the level of compensation. Specifically, if a country’s whole leave duration is paid, it was coded as fully paid; otherwise, it was coded as partially paid. If a country’s compensation is mostly (i.e., half or more of duration) at high flat rate (€1,000/month or $1,342.45/month) or 66% of earnings or more, it was coded as high rate compensation as suggested by researchers (Moss, 2014); otherwise, it was coded as low rate compensation. If a country does not grant leave or does not compensate the leave, it was coded as no leave or no payment. Accordingly, countries were categorized and scored from 0 (no leave or no payment, e.g., Spain, Greece, Netherlands, the United Kingdom, Ireland, the United States, etc.) to 4 (fully paid mostly at high rate, e.g., Sweden, Finland, Norway, Iceland, Slovenia, Estonia, etc.).

Flexible use of parental leave indicates whether the policy allows parents to take leave in different ways. More options to take leave flexibly give parents more leeway to make their arrangements to reconcile work and family responsibilities. Therefore, countries with more flexibility options were considered more supportive and scored higher. Overall, there are 7 types of flexibility granted in policies across countries (e.g., taking full-time or part-time leave, taking leave in one block of time or several blocks, transferring leave to a non-parent caregiver, taking leave at any time until the child reaches a certain age, etc.). Countries with no leave or no flexibility allowed were scored as 0 (i.e., Mexico, Switzerland, and Turkey), while countries with 5 to 6 types of flexibility granted (i.e., Sweden, Germany, Norway, Slovenia, Belgium, and Iceland) were scored as 3 and countries with all 7 types of flexibility available (none in this research) would be scored as 4.

ECEC coordination indicates the integration level between parental leave and ECEC policy, which was examined based on 1) whether ECEC entitlement is granted at or before the end of leave, regardless of compensation level; 2) whether ECEC entitlement is granted at or before the end of well-paid leave (i.e., leave that is paid for half or more of duration at high flat rate); and 3) the length of gap that occurs when ECEC entitlement is not granted at or before the end of leave and well-paid leave. If no gap or a smaller gap (i.e., less than 12 months) exists between leave and ECEC entitlement, a higher level of policy integration is indicated, which would better help parents address work-family conflict. Empirically, countries’ leave and ECEC policy integration levels range and were scored from 0 (i.e., no leave or no ECEC entitlement in Canada, Iceland, Israel, Italy, Japan, Mexico, Slovak Republic, Switzerland, the United States, and Turkey) to 4 (i.e., an ECEC entitlement with no gap between ECEC and leave as well as between ECEC and well-paid leave in Sweden, Germany, Finland, Norway, Slovenia, and Denmark).

Finally, flexible work coordination indicates the integration between parental leave policy and flexibility policy, which was assessed based on whether parents are granted an entitlement to flexibility in work arrangements after the leave ends and the number of options available to them. Countries that grant parents entitlements to more options of flexible work arrangements after the end of leave were considered having a higher policy integration level. In this research, countries were categorized and scored as follows: with no leave or no flexible work arrangement entitlement (scored as 0, e.g., the United States), granting only breastfeeding break entitlement (scored as 1, e.g., Estonia), with additional entitlement to deciding when to start and finish daily work (scored as 2, e.g., Iceland), granting additional reduced work hours and/or part-time work entitlement (scored as 3, e.g., Sweden), and having additional entitlement to reduced work hours, protected and prorated part-time work, and/or other types of flexible work arrangements (scored as 4, e.g., Belgium).

A composite score was produced by summing up all scores obtained from the aforementioned indicators for each country. This composite score can range from 0 to 24. A higher score means a higher level of supportiveness in terms of generosity and comprehensiveness of work-family policies.

Gender Equality Index (GEI)

The GEI reflects the level of policy effort a country has made to promote gender equality. It is formed of the aforementioned six indicators and an additional seventh indicator of equal-share-promoting effort that indicates how many measures in the policy encourage fathers’ use of leave to promote gender equality (see Table 1). Arguably, the existence of comprehensive work-family policy per se could be seen as an effort to enhance gender equality because, as revealed by research, women have experienced higher levels of work-family conflict and faced economic disadvantages due to traditionally assigned caregiver roles. Hence, enacting work-family policies that can help reduce work-family conflict and tighten women’s attachment to employment (Ruhm, 2011) may actually promote gender equality. In fact, studies have found that comprehensive statutory work-family policies that provide generous paid leave and ECEC services help promote gender equality through increasing mothers’ job retention and female labour participation rates as well as reducing the gender wage gap (Datta Gupta, Smith, & Verner, 2008; Lefebvre & Merrigan, 2008; Misra & Strader, 2013; Pylkkänen & Smith, 2003). Hence, it is theoretically and empirically reasonable to include the above six indicators that measure the generosity and comprehensiveness of work-family policies in this GEI Index to gauge the level of policy effort countries have made to promote gender equality. These six indicators were measured in the same way as previously discussed. The additional indicator of equal-share-promoting effort assesses direct methods countries take to encourage equal share of leave between parents, and it was measured using a 5-point scale based on the number and/or type of progressive or extra incentives (e.g., transferrable individual entitlement of leave or compensation, non-transferrable individual entitlement of leave or compensation, bonus leave, bonus compensation, father’s quota of leave or compensation, etc.) designed to increase fathers’ use of leave and share of childcare. Countries that use a more progressive incentive (i.e., non-transferrable individual entitlement) or more types of incentives were rated with a higher score.

I argue that these seven indicators together can better capture the variability in countries’ underlying policy logic and, hence, more accurately differentiate countries’ effort and ability to promote gender equality through a net of work-family policies. For instance, when looking at the indicator of equal-share-promoting effort alone without taking into account the first six indicators, Finland would be considered to be making less policy efforts than the United States does to promote gender equality as Finland grants family entitlement to leave with no additional incentives to encourage fathers’ use of leave, while the United States grants non-transferrable individual entitlement. However, studies have shown that the provision of payment (especially payment at high rate) in leave policy increases fathers’ use of leave (Appelbaum & Milkman, 2011; Bygren & Duvander, 2006; Houser & Vartanian, 2012; S. Lewis & Smithson, 2001) and that statutory ECEC services have positive effects on mothers’ labour participation and earnings (Lefebvre & Merrigan, 2008; Misra & Strader, 2013; Pylkkänen & Smith, 2003). Thus, Finland’s high generosity and comprehensiveness level of work-family policies (e.g., providing well-paid leave and an ECEC entitlement with no gap between ECEC and leave) measured by the first six indicators can actually reflect its higher level of policy effort and ability to promote gender equality relative to the United States where neither statutory paid leave or ECEC is granted. On the other hand, without taking into account the seventh indicator of equal-share-promoting effort, countries with a similar generosity and comprehensiveness level of work-family policies cannot be further differentiated based on whether they have additional incentives in place to promote gender equality through encouraging more equal share of leave and childcare between parents.

In other words, the GEI consisting of all seven indicators can better evaluate the level of effort made to enhance gender equality that is manifested in the designs of work-family policies as a whole across countries. A composite score was generated by summing up all scores obtained from all seven indicators of the GEI for each country. This composite score ranges from 0 to 28. A higher score indicates more efforts a country has made to promote gender equality through work-family policies.

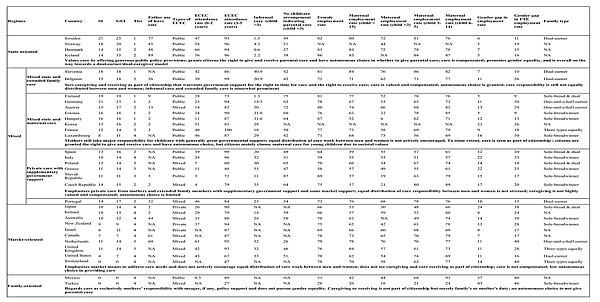

Table 1 Indicators and scale of Supportiveness Index and Gender Equality Index

|

Indicators |

Scale |

|

Eligibility |

0= no leave entitlement 1= 4 or more requirements to meet to be eligible 2= 2 to 3 requirements to meet to be eligible 3= 1 requirement to meet to be eligible 4= universal entitlement (e.g. all employees or all residents are eligible) |

|

Length of leave |

0= no leave entitlement 1= 3 months or less 2= 4 to 12 months 3= 13 to 24 months 4= more than 24 months |

|

Payment |

0= no leave or no payment 1= partially paid, mostly at low rate (< 66% of earning) 2= fully paid, mostly at low rate 3= partially paid, mostly at high rate (> 66% of earning) 4= fully paid, mostly at high rate |

|

Flexible use of parental leave |

0= no leave or no flexibility allowed 1= allow 1 to 2 types of flexibility in the use of leave 2= allow 3 to 4 types of flexibility in the use of leave 3= allow 5 to 6 types of flexibility in the use of leave 4= allow 7 types of flexibility in the use of leave |

|

ECEC coordination |

0= no leave or no ECEC entitlement 1= have ECEC entitlement with gaps between leave and ECEC as well as between well-paid leave and ECEC 2= have ECEC entitlement with no gap between leave and ECEC but with gaps larger than 12 months between well-paid leave and ECEC 3= have ECEC entitlement with no gap between leave and ECEC but with gaps equal to or less than 12 months between well-paid leave and ECEC 4= have ECEC entitlement with no gap between leave and ECEC as well as between well-paid leave and ECEC |

|

Flexible work coordination |

0= no leave or no flexible working arrangement entitlement 1= only breastfeeding break entitlement 2= additional flexible working arrangement entitlement, i.e. deciding when to start and finish daily work 3= additional reduced working hours and/or part-time work entitlement 4= additional reduced working hours, protected and prorated part-time work, and/or other types of entitlement |

|

Equal share promoting effort |

0= no leave or no measure to promote gender equality 1= transferrable individual entitlement of leave or benefits or mixed entitlement introduced 2= transferrable individual entitlement of leave or benefits or family entitlement plus bonus or father’s quota of leave or benefits introduced 3= non-transferrable individual entitlement of leave and benefits introduced 4= non-transferrable individual entitlement or father’s quota plus bonus leave or benefits introduced |

Source: Created by the author

The Care-Employment Analytic Framework

As discussed previously, this two-dimensional framework, informed by the works of feminist welfare state scholars (Daly & Lewis, 2000; Gornick & Meyers, 2003; Knijn & Kremer, 1997; J. Lewis, 1997; Zimmerman, 2013), further compares countries in terms of how they regard and distribute care responsibility between state, market, family, and fathers and mothers as well as whether their work-family policies support parents providing care to their children without sacrificing their careers and income. Specifically, the dimension of care examines whether a policy regime regards care as a private matter or part of citizenship that warrants government support through collective effort; whether a policy regime grants citizens the right to time for care and the right to receive care; whether a policy regime values care enough to provide payment; whether a policy regime allows citizens latitude in deciding whether to give care; and how a policy regime distributes care responsibility among state, market and family as well as between fathers and mothers. This care dimension is indicated by the following indicators: 1) the policy’s supportiveness level measured by the SI; 2) gender equality level of policy measured by the GEI; 3) types of ECEC (i.e., public, private, or mixed); 4) attendance rates at ECEC services for young children under three; 5) the proportion of young children under three cared for by informal caregivers (e.g., grandparents, relatives, neighbours, nannies, etc.); 6) the proportion of children under three not using formal and informal childcare arrangements during a typical week (i.e., indicating parental care); and 7) fathers’ use of leave. Data for indicators 3) to 7) were retrieved from the OECD family database information available in 2014. Higher SI scores, a higher portion of public ECEC, and higher ECEC attendance rates would indicate that a policy regime is more likely to see care as part of citizenship that warrants government support through collective effort, grants citizens the right to time for care and the right to receive care, values care enough to provide compensation or financial support, allows citizens latitude in deciding whether to give care by themselves or use formal ECEC services, and emphasizes the state’s responsibility to provide care. Higher GEI scores and higher fathers’ leave use rates indicate that a policy regime is more conducive to encourage an equal share of caregiving between parents and promote gender equality. On the other hand, a higher level of indicators 5) and 6) represents that a policy regime is more likely to view care as a private matter and places care responsibility largely on the market and families.

The employment dimension examines whether a policy regime supports or encourages citizens, especially women (traditionally assigned caregivers), to be workers and caregivers/parents simultaneously. This dimension is indicated by female employment rates, maternal employment rates for children under the age of 15 (that can be further broken down as employment rates of mothers with children under three, between three and five and between six and 14), employment patterns in couple families with children under three years of age (i.e., three family types including sole-breadwinner/one full-timer, one-and-a-half/one full-timer and one part-timer, or dual-earner/two full-timers family[6]), gender gap in employment rates regardless of whether they are working part-time or full-time, and gender gap in full-time equivalent (FTE) rates, that is, the difference between men and women if they are working full-time (OECD, 2014b). Data for these indicators were retrieved from the information of the OECD family and employment databases, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, and country notes published by the International Network on Leave Policies and Research available in 2014. Higher levels of female employment rates, higher employment rates of mothers with children under and above three and higher rates of dual-earner families as well as smaller gender gaps in employment rates and in FTE rates would indicate that a policy regime is more likely to support or encourage citizens, especially caregivers, to be workers and parents simultaneously without sacrificing their employment.

Typology construction

Scores of the SI and the GEI and descriptive statistics obtained from the Care-Employment Analytic Framework indicators as well as informed and theory-driven judgement were used together to identify and construct a typology of OECD countries based on their characteristics of policy designs and care and employment outcomes/patterns. Specifically, countries were first broadly classified into four tier groups based on their respective scores for the SI. The first tier group countries (e.g., Sweden) generally have the most generous and well-coordinated work-family policies, while the fourth tier group countries (e.g., Turkey) have the least generous and coordinated policies. These clusters were then further analysed, verified, and refined through reviews of countries’ scores and statistics of the GEI and care-employment indicators as well as their historical, political, economic, and social contexts of work-family policy development. Consequently, the emerging typology reflects both quantitative (statistical) and qualitative (theoretical) characteristics that converge and differentiate countries[7] (see Appendix A).

Countries that are characterized by the most generous and well-coordinated policies, largely publicly funded and managed ECEC, high ECEC attendance rates, very low informal care rates, low to somewhat moderate parental care rates, relatively high fathers’ leave use rates, very high female employment rates, high maternal employment rates, small gender gap in employment rates, small to moderate gender gap in FTE rates, and generally dual-earner family type were classified as the state-oriented caring policy regime, which recognizes caregiving is part of citizenship and helps parents give care without sacrificing their employment. Countries that are characterized by various combinations of caregiving from the state, parents, extended family members, and the market were identified as having a mixed caring policy regime. Based on the proportion of care responsibility taken by the state, market, and family, respectively, indicated by the generosity level of policies, types of ECEC and rates of using ECEC, informal care or parental care, as well as employment outcomes, these countries were further categorized into three subgroups: mixed state and extended family care, mixed state and maternal care, and private care with supplementary government support. Countries that are characterized by using market means to address care needs indicated by the least generous and coordinated policies and mainly private or mixed types of ECEC, moderate to high ECEC attendance rates, moderate to high informal care, moderate to high female employment rates, low to moderate maternal employment rates, and generally large gender gaps in employment rates were considered as having a market-oriented caring policy regime. Finally, countries that are characterized by the least generous policies, very low ECEC attendance rates, lowest female employment rates, lowest maternal employment rates, and largest gender gaps in employment rates were classified as having a family-oriented caring policy regime (see Appendix A).

The construction of a typology is a reiterative process and does not aim to create types that represent a perfectly clear-cut distinction among countries. Rather, this typology reveals a spectrum of the complicated and dynamic nexus of the state, market, and family in providing care as well as resulting patterns of caregiving and employment within and across countries. It is argued that the approach used in this research provides simplicity in comparing and classifying countries without losing complexity and diversity within and across countries, though admittedly, the regime typology approach implies a trade‐off: it provides a bird’s eye view of regimes’ contours. In other words, this approach enhances an understanding of the big picture rather than the detailed characteristics of various social programs (Arts & Gelissen, 2002; Ebbinghaus, 2012; Esping-Andersen, 1990). However, this macro comparative understanding should be sufficient to reveal the socially constructed nature of policy regimes and to offer knowledge to support or guide change efforts that aim at improving work-family policies to better support working parents, promote gender equality, and increase positive child outcomes (see Appendix A).

3 Results

3.1 Ranking OECD countries: Supportiveness level and gender equality

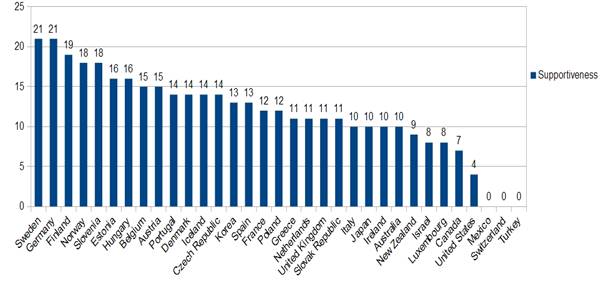

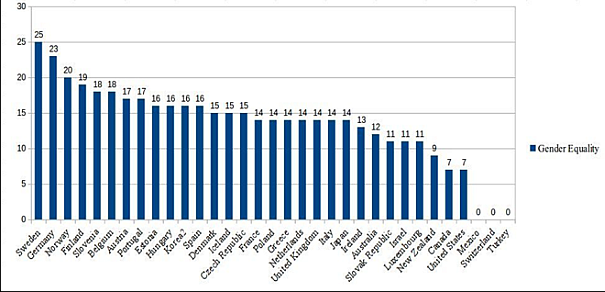

Based on the SI, 33 OECD countries score from 0 to 21. Sweden and Germany have the highest score of 21 and rank 1st, while the United States has a score of 4 and ranks 30th. Mexico, Switzerland, and Turkey have a score of 0 and rank last as presented in Figure 1. Based on the GEI, 33 OECD countries score from 0 to 25 with Sweden ranking 1st and the United States scoring 7 and ranking 29th. Mexico, Switzerland, and Turkey again rank last with a score of 0 on this index, as showed in Figure 2.

Figure 1 Supportiveness Index results: Supportiveness level of work-family policies across OECD countries

Source: Author’s analysis based on the data from Moss (2014) and OECD (2010, 2014i, 2014g)

Figure 2 Gender Equality Index results across OECD countries

Source: Author’s analysis based on the data from Moss (2014) and OECD (2010, 2014i, 2014g)

OECD countries are further divided into four tier groups based on the results of the SI and the GEI. Sweden, Germany, Finland, Norway, Slovenia, Estonia, and Hungary are in the first tier group, which is characterized by having the most generous and comprehensive work-family policy system that provides a high level of supportiveness (scoring from 16 to 21 and ranking 1st to 6th on the SI) to help working parents fulfill responsibilities from both work and family domains. These countries have relatively few requirements for eligibility and thus can cover more employed parents. They provide longer paid leave periods and allow flexibility in the use of leave. More importantly, the leave policy scheme in these countries is well coordinated with ECEC entitlement and flexible work time entitlement (Moss, 2014; OECD, 2010, 2014h, 2014g). In that case, ideally, it is more likely for parents in these countries than those in others to enroll a child in ECEC around the end of entitled paid leave and to be able to request flexible work arrangements when needed. Therefore, the policy systems in these countries are more likely to help reduce work-family conflict. When factoring in the equal-share-promoting effort indicator, however, two countries, i.e., Estonia and Hungary, fall out from the first tier group because they do not provide any measure to promote gender equality (Korintus, 2014; Pall & Karu, 2014). Germany becomes the 2nd rank due to a moderate incentive measure, whereas Sweden remains at the 1st rank because it has the policy packages with the most measures to enhance the possibility that fathers take leave. Norway has a higher score for this indicator and hence is advanced on rank, while Finland and Slovenia gain no point for this indicator since they mainly provide family entitlement which is shared by parents, usually with mothers taking most, if not all of the leave period.

Eight countries, including Belgium, Austria, Portugal, Denmark, Iceland, the Czech Republic, Korea, and Spain, are in the second tier group. This group of countries has work-family policy systems that provide a moderate to generous level of supportiveness (scoring from 13 to 15 and ranking 8th to 14th on the SI) to help working parents reconcile work and family obligations. In general, although most countries in this group have similar scores for eligibility and length of leave as those of their counterparts in the first tier group, they allow fewer types of flexibility in the use of leave and less generous payment for leave (e.g., no payment in Spain and partial or low-rate payment in most countries). The leave policy schemes in these countries are also less coordinated with ECEC and flexible work time entitlements; many countries (e.g., Belgium, Austria, Portugal, Iceland) have gaps between ECEC and leave while some countries (e.g., the Czech Republic) do not provide these entitlements at all (Moss, 2014; OECD, 2010, 2014g, 2014k). When it comes to the gender equality measure in the leave policy scheme, Denmark, Iceland, and the Czech Republic have a lower score of 15 on the GEI, since they provide a mixed entitlement of leave and benefits without sufficient incentive measures in policy to encourage parents sharing the leave period more equally, though Denmark has an industrial collective agreement that introduces paid fathers’ quota of parental leave (Moss, 2014; OECD, 2014i). Belgium, Portugal, Korea, and Spain have higher scores on the GEI as they introduce a non-transferrable individual entitlement of leave and benefits (Moss, 2014; OECD, 2014i).

France, Poland, Greece, the Netherlands, the UK, and the Slovak Republic are clustered in the third tier group. Generally, these countries have a meagre to moderate work-family policy scheme (scoring from 11 to 12 and ranking 16th to 18th on the SI) compared to their counterparts in the first two tiers. Although they have similar scores for eligibility and length of leave as those of the first-tier and second-tier countries, most countries in the third tier do not provide payment for leave taken (e.g., Greece, the Netherlands, and the UK) or provide only meagre wage replacement (e.g., France) (Moss, 2014; OECD, 2014i). The countries in this group also have less coordination among parental leave, ECEC, and flexible work arrangement entitlements. When taking into account gender equality, findings show that these countries generally provide some measure or incentive to motivate parents sharing leave equally except for the Slovak Republic where there is no measure of encouraging fathers to take leave (Moss, 2014; OECD, 2014i). Hence, the Slovak Republic falls into the fourth group when gender equality measures are taken into consideration.

The United States is classified into the fourth tier group along with 11 other countries, including Italy, Japan, Ireland, Australia, New Zealand, Israel, Luxembourg, Canada, Mexico, Switzerland, and Turkey. The countries in this group have the least comprehensive or least generous policies with scores ranging from 0 to 10 and ranking 22nd to 31st on the SI. Three of them, i.e., Mexico, Switzerland, and Turkey, do not have statutory parental leave entitlement. Among the remaining nine countries, one of them, that is the United States, has only a short leave period of three months; four of them (i.e., Ireland, New Zealand, Israel, and the United States) have no payment for the leave taken. Additionally, these countries have the least integrated policy system, as only four countries (i.e., Ireland, Australia, New Zealand, and Luxembourg) have ECEC entitlements, but with gaps, and six countries (i.e., Italy, Japan, Ireland, Australia, New Zealand, and Israel) have flexibility policy entitlements (Moss, 2014; OECD, 2014i). When it comes to gender equality, however, among countries that have statutory parental leave, most have moderate to progressive measures (e.g., non-transferrable individual entitlements of leave, father’s quota, bonus leave, or all of them) to encourage parents to share leave more equally. New Zealand and Canada are two exceptions. They do not have any particular measure to motivate fathers to take leave (Moss, 2014; OECD, 2014i).

3.2 Reconciling care and employment: A typology of policy regimes

Based on the four tier groups built on countries’ scores on the SI and GEI as well as countries’ characteristics of childcare arrangements, fathers’ use of leave, female and maternal employment, employment patterns in couple families with children under three years of age, and the gender gap in employment captured by the indicators of the care-employment analytic framework, I further constructed a typology of four policy regimes.

State-oriented caring policy regime

Nordic countries, particularly Sweden, Norway, Denmark, and Iceland, demonstrate a state-oriented caring regime that is characterized by high levels of supportiveness and gender equality in work-family policy designs, high ECEC attendance rates, larger fathers’ share of leave, high female and maternal employment rates, and dual-earner/dual-caregiver model (Fraser, 1994; Gornick & Meyers, 2004; Misra, Moller, & Budig, 2007). These countries emphasize governmental intervention and usually adopt a universal approach to social provision. Their aim is to promote employment of mothers and equal share of care labour in households (Beneria, 2010). A gender dimension has been added to the measures used in these countries, especially Sweden and Norway, as early as in the 1970s (Hirdman, 1994, as cited in Bjornberg, 2000; Haas, 2003). Since the mid-1970s, policies in Norway and Sweden have recognized citizens’ dual roles of workers and parents through expanded entitlements to maternity, paternity and parental leave (Leira, 1998). Norway and Sweden also introduced father’s quota of leave in the 1990s to promote equal sharing between parents in caring for young children (Leira, 1998), though Denmark and Iceland show somewhat moderate progress in terms of sharing care responsibility (Moss & Deven, 2006). Overall, these four countries provide generous leave provisions in terms of length of leave and payment. Most of them also provide statutory entitlement to flexible work arrangements. Work-family policies in these countries grant parents the right to time for care and grant children the right to receive care from parents. Parental care is viewed as a form of labour and is valued enough to be compensated. They also reconcile parents’ right to autonomous choice not to provide care and children’s right to receive quality care by granting ECEC entitlements around or even before the end of paid parental leave and by spending considerable amounts of public funding in providing quality services (Ruhm, 2011). Therefore, in these countries, care responsibility is distributed between the state and family with the greatest degree of governmental support, which is evident in that the attendance rates at ECEC programs for children under age three in these countries are generally high (47%-66%) (OECD, 2014k); the proportion of children under age three cared for by informal childcare providers is low (0.6%-2.2%); and the proportion of this age group of children with no usual formal and informal childcare arrangements is relatively low (OECD, 2014l).

The ratios of fathers to mothers using parental leave in these countries, especially Iceland (89%) and Sweden (77%), are much higher than those of most OECD countries (OECD, 2014j). Accordingly, women, including mothers with young children in these countries, are encouraged to participate in paid work. Hence, in these countries not only are female (25-54 age cohort) employment rates very high; the employment rates of mothers with children under three years of age are also quite high (OECD, 2014e). Consequently, the gender gaps in employment rates in these countries are generally small (less than 10%) (OECD, 2014f, 2015d). Although the gender gap in the FTE rates in these countries are slightly larger, which indicates some women work part-time (OECD, 2014f, 2015d), the most common employment pattern in couple families with children under three years of age is dual-earner, specifically two full-timers (Moss, 2014; OECD, 2014d). In sum, these countries value unpaid care work and paid work simultaneously, and they are willing to invest in policies that help working parents reconcile work and family obligations and transform gender norms by encouraging a more equal distribution of care labour between men and women.

Market-oriented caring policy regime

Ten countries, including Japan, New Zealand, Israel, Ireland, Australia, Canada, the Netherlands, the UK, the United States, and Switzerland, represent a market-oriented policy regime that regards care work as a private matter requiring private solutions instead of governmental interventions. These countries are characterized by preference for market-oriented provision, meagre and non-universal benefits, or means-tested benefits when programs do exist (Bolzendahl & Olafsdottir, 2008; Misra et al., 2007). In general, these countries provide meagre work-family policies indicated by their scores on the Supportiveness Index and the Gender Equality Index. As a result, parents in these countries have to rely mainly on market means to address childcare needs and work-family conflict issues, which not only enhances inequalities between families through deepening the burdens of low-income families but also contributes to unequal care distribution between fathers and mothers within households. When a market solution is insufficient, unavailable, or unaffordable, care responsibilities remain within the families (Beneria, 2010), which means mothers or informal caregivers, such as grandparents (OECD, 2014l), have to take responsibility for care work. Unequal shares of childcare between men and women result in gender inequality in employment outcomes. For instance, in the United States, 36% of women (versus 6% of men) with children under six are not in the labour force (U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2014b); 16% of women (versus 5% of men) with children under six work part-time (U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2014b); the gender gap in employment rates among people ages 15-64 years old is moderate (11%), and the gender gap in FTE is moderate (16%) (OECD, 2014f, 2015d). Other countries share similar patterns with the United States.

Because of limited governmental support, parents tend to use market means to care for children. Without progressive interventions, when market means cannot cover all care needs, care responsibility would be more likely to fall on the shoulders of mothers, which is reflected in the repressed employment rates of mothers with young children (OECD, 2014e). It also results in a higher gender gap in both employment rates and FTE rates (OECD, 2014f, 2015d) in comparison to Nordic countries, with Japan having even lower maternal employment rates and a higher gender gap in employment and FTE rates. This is perhaps due to the influence of traditional culture, conservative family norms, and negative attitudes toward the role of state in providing childcare (Esping-Andersen, 1997; Jappens & Van Bavel, 2011; Lokteff & Piercy, 2012; Weinraub, 2015). The Netherlands, however, has higher female and maternal employment rates than its counterparts (OECD, 2014e), because Dutch parents frequently use privately-run ECEC services for children under three (OECD, 2014k) and because the Netherlands intends to address work-family conflict issues by encouraging parents to work part-time (Haas, 2003). Since part-time work is common in the Netherlands, policies that do not penalize part-timers in terms of wages, promotions, and fringe benefits have been developed (Beneria, 2010). But women’s disproportionate taking of part-time jobs to fulfil family responsibility per se still represents a form of gender inequality (Beneria, 2010; OECD, 2015d). Overall, policies of this type of regime reflect a view that does not see giving and receiving care as part of citizenship but merely as a private matter; hence, giving and receiving care are neither supported nor compensated through collective efforts. These policy regimes also do not support parents’ autonomous choice to not give care because most of them do not stipulate ECEC entitlements and most ECEC services available to children under three are privately-run, which may not be affordable to all parents. With the state’s marginal involvement, care responsibility is left to the negotiation between the market and family, and without active measures, the task of negotiating or picking up the care work not covered by the market is often left to mothers. Although governments in these countries recently encouraged employers to help employees through family-friendly workplace practices, such as flexible work time arrangements (OECD, 2014g), these kinds of practices are currently not the norm and usually only available to a rather small group of employees. Thus, in these countries, working parents have to manage work-family conflicts mostly on their own, and, while doing so, gender equality is compromised.

Family-oriented caring policy regime

Mexico and Turkey fall into a family-oriented policy regime. Mexico and Turkey grant only three to four months of non-transferrable maternity leave and do not have paternity or parental leave, which indicates that, in these countries, care is regarded as exclusively a mother’s responsibility. Although Mexico has publicly-funded-and-managed ECEC services for children under and above three years of age, the attendance rate is extremely low (8.3%) for children under three. There are no available data regarding the attendance rate for children under three in Turkey, but the attendance rate for Turkish children above three is low (27%) (OECD, 2010, 2014k). Since the attendance rate for this age group of children is usually high across countries, it is reasonable to estimate that the attendance rate for children under three in Turkey is probably much lower. The absence of parental leave and low attendance rates at ECEC services in these countries suggest that it is families, especially mothers, taking responsibility for childcare. This claim seems supported by the employment patterns of women and mothers in these countries. According to OECD (2014c), Mexican and Turkish women have the lowest labour force participation rates (respectively, 47.8% and 33.7%) among OECD countries. Mexico and Turkey also have the lowest female employment rates (respectively, 51% and 28%) and low employment rates for mothers with children under three (respectively, 44% and 15%) (OECD, 2014e). Mexico has higher maternal employment rates (69%) for mothers with children aged three to five, which may be attributable to higher attendance rates (89%) at ECEC programs for this age group of children, while Turkey still has the lowest maternal employment rates for this group (around 21%) (OECD, 2014k, 2014e). Accordingly, the gender gap in both employment rates and FTE rates are very high (OECD, 2014f, 2015d). With limited support from the government, child care is mainly provided by families, particularly mothers, in countries with this type of regime. On balance, this policy regime does not regard care as part of citizenship but as a family’s, or mother’s, responsibility. Hence, parents’ right to time for care is not fully recognized. Though children’s right to receive care is partly supported through the implementation of paid maternity leave and childcare services, in the long run, it is achieved at women’s, specifically mothers’, expense. Care labour is not equally distributed between men and women. Women’s paid work is not recognized nor encouraged in this policy regime. Arguably, in this regime, work-family reconciliation is maintained mainly through a men-breadwinner and women-housewife family model in which fathers sacrifice time with children and mothers sacrifice career advancement. Gender equality, in terms of employment equality, is not clearly pursued in this regime.

Mixed caring policy regime

The remaining countries demonstrate mixed models of policy regimes where various combinations of caregiving from the state, parents, extended family members, informal caregivers, and the market have formed, which further classifies these countries into three subgroups.

Mixed state and extended family care. The first subgroup, which includes Slovenia and Belgium, manifests mixed responsibility of the state and extended family for childcare with greater work-family policy support that encourages maternal employment (Merla & Deven, 2014; Stropnik, 2014). ECEC services in these countries are predominantly publicly provided (Naumann et al., 2013; OECD, 2010). The attendance rates for children under three are above the OECD average and for children above three are not only above the OECD average but also more than 85% in both countries (OECD, 2014k). Parents in these countries also use some form of unpaid informal care mainly provided by extended family members or friends. The use of other types of childcare, however, is unusual in both countries (OECD, 2014l). Slovenia and Belgium also have flexible work time arrangement entitlements (OECD, 2014g). In the main, this subgroup of countries, to some extent, sees caregiving and receiving as part of citizenship that warrants government support for the right to time for care and the right to receive care. The time parents use to care for children is also valued and compensated. The countries also grant parents the right to autonomous choice to not give care by providing ECEC entitlements and mainly public services. Overall, policies in these countries support parents to reconcile paid work and unpaid care work; women and mothers are encouraged to participate in paid work, which is reflected in their relatively high female labour force participation rates, high female employment rates, and high employment rates for mothers with children both under and above three (OECD, 2014c, 2014e). The prevalence of dual-earner families with children under and above three in both countries further verifies this trend (Moss, 2014; OECD, 2014d). However, care responsibility is still not equally distributed between men and women with fathers’ lower use of leave, which partly contributes to gender gaps in employment rates and gender gaps in FTE rates in Slovenia and Belgium (OECD, 2014f, 2015d).

Mixed state and maternal care. The second subgroup consisting of Finland, Germany, Austria, Estonia, Hungary, Korea, France, and Luxembourg generally shows mixed responsibility of the state and mothers for childcare with moderate to generous work-family policy support. Finland is the only Nordic country that is classified in this subgroup. According to Lammi-Taskula (2008), Finland has a long tradition of full-time employment of women, and policies that support the reconciliation of work and family have been in place since the 1960s. A men-breadwinner family was never firmly established, while a “wage-worker motherhood” emerged before the 1990s (Lammi-Taskula, 2008, p. 135). However, a deep economic recession in the mid-1990s contributed to the emergence of a new gender contract that questions maternal employment. The employment rates of mothers with children under school age decreased from 76% in 1989 to 61% in 1997 (Haataja & Nyberg, 2006, as cited in Lammi-Taskula, 2008) and currently remain at a similar level (OECD, 2014e). Since then, many Finnish families have moved from a dual-earner model towards a male-breadwinner model (Lammi-Taskula, 2008; Moss, 2014). Finnish leave policies support maternal care at least for children under three. In combination with home care leave, families can have 36 months of paid leave, but the leave and payment are both family entitlement without incentives to encourage fathers to take leave. As a result, mothers take most leaves while few fathers use the leave (Lammi-Taskula, 2008; OECD, 2014j). Hence, care work is not equally distributed between fathers and mothers in Finland. Although there is an ECEC entitlement in Finland and the services are mainly publicly-funded-and- managed and available to children under three around the end of well-paid leave, the attendance rates for children both under and above three are not high and are well below OECD averages. Clearly, in Finland childcare is commonly regarded as mothers’ job; current policies do not redistribute care responsibility between men and women (Haas, 2003; Lammi-Taskula, 2008). This “maternalist” assumption (Connell, 1990, as cited in Moss & Deven, 2006, p. 277) embedded in policies and practices jeopardizes gender equality at least in terms of employment outcomes.

Germany, Austria, and France provide long job-protected leaves, around three years per child in Germany and France and two years in Austria (Blum & Erler, 2014; Fagnani, Boyer, & Thévenon, 2014; Haas, 2003; Moss & Deven, 2006; Rille-Pfeiffer & Dearing, 2014). But Austria offers only a low flat rate of payment (Rille-Pfeiffer & Dearing, 2014); Germany provides high wage replacement but only for partial leaves, while France only grants a low-rate payment for partial leaves (Blum & Erler, 2014; Fagnani et al., 2014), indicating the somewhat low status of caregiving in these countries. Although some forms of incentives have been introduced in leave policies to encourage fathers to share care in these three countries, the use of leave by fathers is still very low (OECD, 2014j), indicating that mothers still take on major responsibility for childcare. Accordingly, the maternal employment rates of mothers with children both below and above three are moderate, around OECD averages (OECD, 2014j), and men-breadwinner families with children under three are common in these three countries (Moss, 2014). Estonia and Hungary have relatively generous parental leave, but the leave is entirely a family entitlement, and there is no incentive measure in their policies to encourage fathers to use the leave (Korintus, 2014; Pall & Karu, 2014). Accordingly, fathers in Estonia and Hungary rarely use the leave (OECD, 2014j). Thus, although the Estonian and Hungarian governments see child care as part of citizenship that requires collective efforts to grant parents the right to time to give care and value caregiving to some extent to compensate it mostly with high-rate wage replacement, the policies reflect the belief that mothers should be the primary caregivers. There is no encouragement of equal distribution of care responsibility between fathers and mothers in families. The attendance rates for children under three in Estonia and Hungary are quite low due to a shortage of formal ECEC program slots and preference for maternal care for young children (Korintus, 2014; OECD, 2010, 2014k; Pall & Karu, 2014). Consequently, Estonia has very low employment rates of mothers with children under three, and Hungary has the lowest rate among OECD countries (OECD, 2014e). Unsurprisingly, the sole-breadwinner model is predominant in families with children under three (Moss, 2014; OECD, 2014d).

Since the 1990s, South Korea has experienced demographic changes, including a decrease in male wages, an increase in women’s labour force participation, low fertility rates, and a decline in the sole-breadwinner family form. Hence, Korean policy has gradually moved from “extensive familialism” to a “modified familialism” model that includes government intervention to help families with care responsibilities (Peng, 2010, as cited in Beneria, 2010, p. 1519). Specifically, Korea grants parents an individual entitlement of 12 months of leave with low-rate wage replacement (OECD, 2014i). But because of meagre compensation and the lack of incentives, Korean fathers rarely use the leave (OECD, 2014j), which prevents equal distribution of care responsibility between men and women within families. On the other hand, Korea provides publicly-funded-and-managed ECEC services for children under and above three (OECD, 2010), which may somewhat relieve families, particularly mothers, of some care demands and encourage mothers to work. Overall, the Korean female labour force participation rates are still quite low among OECD countries (OECD, 2014c), and, hence, the gender gap in employment rates in Korea is much higher than in most countries (OECD, 2014f, 2015d).

Luxembourg has a shorter leave and compensates the time parents take to care for children with a flat-rate wage replacement. Although the leave is an individual entitlement, there is no incentive to redistribute care work between men and women. When both parents apply for the leave, the mother has priority (Zhelyazkova, Loutsch, & Valentova, 2014). Clearly, compared to fathers, mothers are regarded as the primary caregivers. In Luxembourg, there is a gap between ECEC entitlement and the end of leave (Zhelyazkova et al., 2014), but the ECEC services available to children under and above three are mainly publicly funded and managed (OECD, 2007, 2010). With a combination of leave and childcare provisions, in spite of shouldering the majority of care responsibility, mothers are still able to participate in paid work, which is evident in relatively higher employment rates of mothers with children under three in Luxembourg (OECD, 2014e). However, gender gaps in both employment rates and FTE rates are still quite high in Luxembourg (OECD, 2014d, 2015d), partly attributable to the unequal share of childcare between men and women. This subgroup of countries treats care as a joint public and private responsibility. Parents are granted the right to take paid time off to care for children and are able to use mainly publicly-funded-and-managed childcare services. Nevertheless, governments in this subgroup do not promote equal distribution of care work between men and women. Care work is generally considered as mothers’ jobs but with government supports. Thus, though women are encouraged to participate in paid work, mothers usually scale back labour force participation. In other words, governments in this subgroup somewhat help parents reconcile work and family responsibilities, but fathers and mothers may experience work-family conflicts differently due to the unequal share of unpaid care work.

Private care with supplementary government support. The third subgroup consisting of Spain, Italy, Poland, Greece, the Slovak Republic, and the Czech Republic demonstrates a policy regime that emphasizes private care from mothers and extended family members with supplementary government support. Equal distribution of care responsibility between men and women is not stressed in the policies of most of these countries. Spain has moved from a patriarchal society to a society where gender equality has become an important goal. Since the 1990s, the number of women who entered the labour market has increased significantly (Beneria, 2010). However, childcare in Spain is still seen as mothers’ responsibility, with help from extended family members, instead of fathers’ or public responsibility that warrants collective intervention. Although Spain offers a lengthy parental leave (around three years from birth), the leave is not paid, which indicates the low status of caregiving. There is no incentive in place to encourage fathers’ use of leave. Fathers in general rarely use the leave (Escobedo, 2014). Spain has an ECEC entitlement starting at three years old and provides public services for children under and above three, but the attendance rates for children under three are just around the OECD average (Escobedo, 2014; OECD, 2014k). Accordingly, employment rates of mothers with young children in Spain are moderate and also just around the OECD average (OECD, 2014e).

In response to EU directives, Greece developed parental leave in the 1990s (Haas, 2003). Greek parental leave has remained meagre: unpaid, three months of leave per parent with no incentive to encourage fathers to use the leave (Kazassi & Karamessini, 2014). Comparatively, the Czech Republic, Italy, Poland, and the Slovak Republic provide longer leaves, generally with low-rate payments except for the Czech Republic which offers 70% of previous earnings (Addabbo, Giovannini, & Mazzucchelli, 2014; Gerbery, 2014; Kocourková, 2014; Michoń, Kotowska, & Kurowska, 2014). The leaves in these four countries are family entitlements. Although Italy and Poland provide some measures to encourage fathers’ use of leave, low payments may discourage fathers from actually taking leave. In general, fathers in the Czech Republic, Italy, and the Slovak Republic rarely use the leave (Addabbo et al., 2014; Gerbery, 2014; Kocourková, 2014). Moreover, Italy and the Slovak Republic do not have an ECEC entitlement. Although Greece, the Czech Republic, and Poland have an ECEC entitlement, there is a gap between ECEC entitlement and the end of leave (Addabbo et al., 2014; Gerbery, 2014; Kazassi & Karamessini, 2014; Kocourková, 2014; Michoń et al., 2014). The attendance rates at ECEC services for children under three are very low in these countries (OECD, 2014k). Therefore, mothers and extended family members usually have to take major responsibility for childcare (OECD, 2014l). As a result, in these countries, employment rates of mothers with young children are low (OECD, 2014e), and gender gaps in employment rates and FTE rates are higher than in most OECD countries (OECD, 2014f, 2015d). On average, policies of this subgroup of countries reflect the belief that regards care work as a private responsibility that should be predominantly taken by mothers and extended family members. Governments provide only supplementary assistance. The redistribution of caregiving between men and women at home is also not a major concern of these governments, though some progress has slowly been made in Spain, Italy, and Poland. The sole-breadwinner is the most common pattern in couple families with children under three (Moss, 2014; OECD, 2014d). Caregiving in this subgroup of countries is not highly valued and tends to be divided along gender lines. Parents have to use private solutions to address work-family conflict issues at the expense of gender equality.

Portugal is the only country in the mixed caring policy regime that cannot be further placed in any identified subgroup. In Portugal, working parents rely on moderate to generous public work-family policy provisions, extended family members, and the market to address childcare needs. The Portuguese government provides three months of leave per parent with low-rate wage replacement (Wall & Leitão, 2014). Leave is an individual entitlement. No extra incentive is adopted to encourage fathers to use leave, but the ratio of fathers to mothers using leave in Portugal (52%) is much higher than that (3%) of the last subgroup (OECD, 2014j). Portugal grants an ECEC entitlement, but it starts from five years old. Hence, there is a gap between the ECEC entitlement and the end of leave (Wall & Leitão, 2014). Also, the ECEC provisions for children under three are mainly privately-run. But the attendance rates at ECEC programs for children under and above three are higher than OECD averages (OECD, 2014k). Using formal ECEC services and informal caregivers (OECD, 2014l) has facilitated high employment rates of mothers with children under three (68%) and above three (79%) (OECD, 2014e) as well as a high prevalence of dual-earner families with children under three in Portugal (Moss, 2014; OECD, 2014d). The Portuguese government also grants parents the right to request flexible work time arrangements. Thus, overall, the Portuguese government recognizes citizens’ right to time for care but the short length of leave and relatively meagre compensation for the leave parents take to care for children indicate that caregiving is not highly valued. With government support, parents still have to rely on extended family members and the market to address childcare needs and work-family conflict issues, which makes Portugal a mixed caring policy regime with a combination of caregiving from the state, extended family members, parents, and the market.

4 Discussion and implications