Provider Perspectives on Child Care in the United States

Elizabeth Palley, Adelphi University School of Social Work, Garden City (NY)

Corey S. Shdaimah, University of Maryland School of Social Work, Baltimore

Introduction

Care work has historically been carried out by women outside of the paid labor force (Duffy, 2011). With the growing movement of middle-class women into the labor force, this work has increasingly become commercialized throughout the world (Folbre, 2012). Care workers generally perform what is considered “family work,” such as cleaning, watching children, and assisting older people, that is often seen as intrinsically rewarding (England & Folbre, 1999) and as a result is poorly compensated in many countries (Duffy, Armenia, Stacey, & Nelson, 2015). As Helena Hirata (2016) noted in her comparison of care workers in Brazil, Japan, and France, “Care work is a prime example of the inequalities intertwined with gender, class and race, as the majority of carers are women, poor, Black and often migrants” (p. 54). This is true in the United States as well (Ergas, Jenson, & Michel, 2017; Folbre, 2012). Child care is one type of caregiving. Despite the fact that the overwhelming majority of U.S. families rely on nonparental care for children before they are 5, child care professionals are among the most poorly paid U.S. workers (Laughlin, 2013; Whitebook, McLean, & Austin, 2016). Their voices are also rarely heard in debates around child care policy and programming that directly affects them and their ability to provide care. This article reports findings from a study of licensed center-based and home-based child care providers in New York State (n = 55), focusing on providers’ perceptions about their profession.

1 Background

According to the most recent census data, the median salary for child care providers is $9.77 an hour (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2015). Few (15%) receive employer-based health insurance, and even fewer receive pension contributions from their employers (Gould, 2015). According to a 2016 report by the Berkley Center for the Study of Childcare Employment, 46% of child care providers receive either Medicaid or food stamps, benefits that are only available to those with incomes low enough to qualify (Whitebook et al., 2016). The study highlights the poverty of child care providers as well as the limited training many receive. Such research suggests that many providers may be unable to pay for training, describing supports for child care providers across the country as “optional, selective, and sporadic” (Whitebook et al., 2016, p. 1).

Contrary to the common belief that child care work is unskilled, and despite the fact that almost anyone can be a child care worker,[1] the child care workforce is neither uneducated nor untrained. Approximately 20% of child care workers have bachelor degrees, and 56% have some postsecondary education (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2016). However, despite attention to the important impact of early childhood experience on the development of the human brain in the past 15–20 years (Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University, 2016), there has been a decline in child care workforce qualifications (Herzenberg, Price, & Bradley, 2005). Between 1983 and 1985, 43% of center-based providers had 4-year college degrees; by 2002–2004, only 30% did. The educational level of providers is important because a more educated child care workforce is more likely to have the skills to provide higher quality care.

Little research has been done on the perspectives of child care providers themselves. That which does exist, such as a 2001 study of professional development in Washington State, suggests that home-based child care providers feel that they are not viewed as professionals by regulators, parents, or center-based providers (Lanigan, 2011). A recent qualitative study conducted in North Carolina suggested that working conditions for child care providers are poor and that providers experience health outcomes associated with poverty (Linnan et al., 2017). In a capitalist society where value is often determined by monetary rewards, the picture painted by the limited research on U.S. child care providers indicates that the profession lacks fundamental respect. One study based on interviews with home-based providers reported similar findings (Tuominen, 2003). Another study of 1,300 randomly selected home-based providers conducted in Illinois found that women who become home care providers are “trying to meet a broad range of mothering responsibilities—including economic provision and commitments to kith, kin, and community” (Armenia, 2009, p. 554).

2 Methods

This article reports findings from focus groups and interviews conducted in rural, urban, and suburban areas of New York State with center- and home-based child care providers. The study was designed to examine how child care providers perceive the impact of policy changes on their work and the families they serve, findings which have been reported elsewhere (Shdaimah, Palley, & Miller, 2018). Here, we focus specifically on providers’ understanding of how others perceive their work, a prominent theme that emerged from our study data. Study data also shed light on what inspired our respondents to become and remain child care providers, despite their sense that child care work was devalued. The data suggest how, as a society that relies heavily on paid providers, we may better ensure a continued supply of highly qualified child care providers.

3 Study Procedures

We chose New York State as our research site. As an early adopter of child care policies and regulations, New York is an ideal site to understand the evolving practice of child care provision. The state’s large size also provided for geographic diversity and, in some locations, racial and socioeconomic diversity (World Population Review, 2018). In creating and recruiting for the study, we reached out to union and nonunion advocates and county-level child care resource and referral centers. These connections allowed us to recruit widely as their e-mail distribution lists reached the overwhelming majority of licensed providers in the respective counties.

We used focus group methods as the most efficient research tool to collect rich data from a relatively large sample, given time and other resource constraints (Hesse-Biber & Leavy, 2006). The group dynamic of focus groups also encourages participants to elaborate on their own views through responding to others, which can give rise to insights not anticipated by researchers (Krueger, 2015). We held focus groups in rural, urban, and suburban locations. For the suburban location, we drew from Nassau and Suffolk Counties. Our urban location was Albany. Rural focus groups and interviews drew from Herkimer, Madison, Sullivan, and Oneida counties. In each location (rural, urban, and suburban), we held two separate groups: one for home-based providers that included family (up to six children) and family group (up to 16 children, depending on their ages and the number of providers on site)[2] providers and the other for center-based providers.

Focus groups were held in public libraries, child care centers, or child care resource and referral centers. Each location was chosen on the basis of convenience for providers in the group and so that we could ensure privacy. We conducted supplemental interviews with five rural providers over the telephone due to difficulties that dispersed rural provides who wanted to participate in the study faced in attending focus groups. For both focus groups and interviews, we used the guide attached as Appendix A. All focus groups lasted between 90 and 120 minutes, and interviews lasted between 20 and 60 minutes; all were digitally audio-recorded. The recordings were transcribed verbatim for purposes of data analysis. In order to protect the confidentiality of study participants, we asked them to choose their own pseudonyms. Cash incentives of $50 were given to each provider who participated in a focus group.[3]

4 Sample

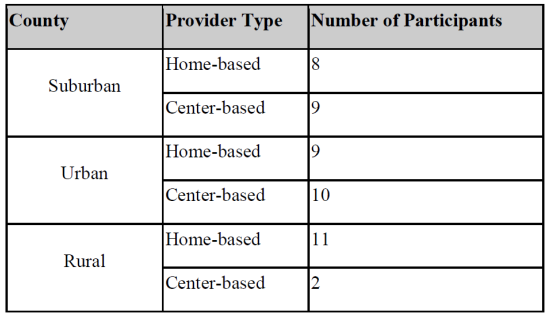

The sample included 49 focus group participants and six interview participants, for a total sample of 55. Table 1 provides a breakdown of focus groups by provider and county type:

Table 1. Focus Group Participant Numbers by County and Provider Type

Most center-based provider focus group participants were directors who were able to provide us with a broad overview of their center’s work. Most worked on site and were in the classrooms often. In addition, many had worked as classroom providers themselves before becoming directors and, therefore, shared the perspective of both a direct provider and an administrator. Study participants had been providing care for between 3 and 30 years. All were women. The majority were White, with some racial/ethnic diversity among the suburban and urban providers, which included providers who self-identified as Black or African American, Hispanic, Hispanic/Black, and Asian.[4] Nearly all providers had a least a high school degree, and the majority for whom we have data also had an associate’s or bachelor’s degree. A number also held master’s degrees, and at least one center director had a Ph.D. Many had degrees related to education and child care, such as early childhood education or child development. Our center-based participants were drawn from a mix of for-profit and not-for profit programs; all home-based providers were for-profit businesses. The sample included a mixture of unionized and nonunionized providers, as well as providers who accepted and did not accept children whose care was government subsidized. We did not include Head Start programs in this sample, as they work within a different set of regulatory and educational policies, although at least one center director (of a large multi-service center) noted having a Head Start program in addition to other child care programs at her site.

5 Data Analysis

To analyze study data, the authors and a master-level social work student who served as a research assistant on the study coded the data using thematic analysis (Thomas, 2006). This involved reading through the transcripts in several iterations to look for patterns and broad themes (Maxwell, 2016). As a form of peer debriefing to enhance rigor, the second author and the research assistant met to review the codes and resolve any differences through discussion and consensus (Padgett, 2012). Codes were developed from sensitizing concepts that were taken from the literature and our own prior research (Bowen, 2006) and ideas that emerged from the data (Padgett, 2012).

The most important emergent theme from our analysis was the disconnect between public perception of the work of child care providers versus their understanding of what they actually do as providers for children, families, and the broader society. This article also reports findings from a secondary analysis of the data, specifically focusing on respondents’ perceptions of how they and others view the work of child care. For this secondary data analysis, the first author reread the original transcripts coding the data that specifically related to respondents’ perceptions of the value or content of their work as well as what they believe others think of their work. All of the themes presented in this article were found across all focus groups.

6 Findings

Our findings indicate that study respondents shared a strong commitment to the children and families they served that drives their work, which we describe as our first theme. Our second theme centers on why respondents do not feel that their work is respected or considered to be professional. Our third theme describes the supports that respondents see as necessary for professional child care practice, which could result from a more accurate estimation of the value of their work.

6.1 Commitment and Emotional Connection to Children

Despite the economic challenges that many respondents faced, they all reported being attached to the children for whom they provided care. Many described frustrations with regulatory requirements and low pay. They continued to work in child care because they loved caring for children whom many described as their own, referring to them, for example, as “my babies.” Home-based providers were particularly likely to note such attachments. When one rural home-based provider discussed the challenges that she faced as a provider, she also pointed to the satisfaction she derived from parents’ appreciation and from witnessing children’s development:

Most parents are awesome. They understand that we essentially assisted them raising their children and they keep us in the loop through college and that is why most of us stay in the field. Not because of the money because it’s really not worth it; not because of any incentive that the state gives us. It’s really the families. It’s watching these little guys turn into great human beings.

Providers’ attachments and a sense of a calling kept respondents in the field of child care, despite their struggles: “As frustrating and irritating as some of the policies and the county and the parents can be, the kids make every minute worth it. That’s what everyone needs to understand” (rural home-based provider).

In a similar vein, providers’ close relationships with children and their families gave them a strong sense of intimacy and familiarity: “We know our babies. We know them because we're with them eight to ten hours a day, we know them better than some of the parents” (urban home-based provider). In the suburban focus groups, home-based providers noted:

JT: I mean we’re not only providers, we’re educators, we-we’re almost like, we’re like those children’s parents

Bernadette: That’s right

JT: because we keep them longer

These study participants formed close bonds with the children and families with whom they worked and saw themselves as instrumental to the children’s upbringing.

Center-based providers shared similar commitment to children. In the suburban focus group, one study respondent left her work with a for-profit child care facility to work for a nonprofit organization:

I really hit the wall as a director when I walked into my toddler room because I had to move a couple of kids out to stay in ratio for licensing and a little 2-year-old ran behind a piece of furniture and said, “No, no, I don’t want to visit today. I don’t want to visit today. I don’t want to go.” And it was just a lightbulb going off for me as a director, “What are we doing, you know, to make money for a corporate entity?” I get capitalism. I’m not against capitalism, but it hit me that this little 2-year-old is a human being. She’s not a pawn on a balance sheet.

Providers’ commitment seemed to go above and beyond what most might expect from a commercial transaction. For example, at least one urban home-based provider reported transporting children in her own car. If she were in an accident, this would place her in a position of personal liability. Another, who served children from a low-income population, including several children on public assistance noted:

I spend a lot of my Christmas money on the kids for clothes….I said to my husband, for example, he says "You go out and spend fifteen hundred dollars a month and you buy all this food and then you give it away.”

Another said that some children in her care always asked for more food.

I noticed at lunch time was the time they got picked up, it was two little kids, and the little boy would always come back and be like "Oh, can I get an extra plate of or a little bit more or seconds" and after a while I said "He's always doing that," so one day I was just like “No.” Because now everybody else is going to ask for seconds and I'm going to have to have double the food, and you could see it in his face, like, hungry. And then I said “Okay,” I said “How about this, I'm going to pack something away.” (urban home-based provider)

Both the home care providers and the center directors suggested that their commitment to the children for whom they cared was more than just a job. They spent their Christmas money on their children, transported them despite their own personal liability, and, in all cases, reported that their strong bond with the children was the primary reason that they worked in child care. This job, they suggested, was one that people did for love, not money.

6.2 Lack of Respect

Both center and home-based respondents felt that child care providers were not respected as professionals. Respondents emphasized what are considered characteristics of professionalism, such as expertise, educational qualifications, licensing requirements, and ongoing career development. Several home-based providers explained that though they started their careers as mothers who babysat other children in order to stay home with their own, they had developed skills by working in the field and seeking additional training. According to one rural home-based respondent:

I think initially in the beginning I was just really more in, I guess, a babysitter role? Because I didn’t really know, I mean I was there as a mother [chuckling] and just kind of cared for the children—like uh you know—like I would as a mother. And then, just over time and taking classes and talking to people and things like that…it kind of evolved from there. We do a little preschool program during the week for our 2- to 4-year-olds; it’s structured, more of a structured day versus this kind of babysitting care.

Although some providers felt respected by parents, others described hearing dismissive comments or having disrespectful encounters. Such remarks included the suburban home-based provider who overheard how parents characterized her: “The parents do not respect us as professionals. There are so many parents that will get on the phone in our presence and say, ‘Oh I’ll be right there, I’m at the babysitters.’ Are you kidding me?”

One of most often noted misperceptions was the importance of care providers’ role as educators. Some, like the following rural home-based provider, juxtaposed her role as a teacher with the misnomer “babysitter”:

It should be a more respected profession. We are important, and we are teaching these kids from 6 weeks on up. I don't think anyone of us sends these kids to school who aren't potty-trained, can tie their shoes, write their first and last name, you know colors, letters, numbers, blah, blah, blah. And you hear of teacher appreciation week, and the teachers this and that. I have wonderful families and they are appreciative, but I just don't like being called a babysitter. There is a difference between what we do.

In addition to academic preparation that providers compared to the work of teachers, many respondents noted the important socioemotional learning that they provided. “It’s more of getting them ready for school but not just in an academic way. It’s empathy. It’s compassion. It’s being good kids” (urban home-based provider). Another urban home-based provider echoed respondents in all groups when she described the multifaceted nature of early childhood education when children were in care for the majority of their waking hours.

I’m an early childhood educator. I’m preparing your children for elementary school. It is my job to make sure that they know the things they need to know to go to kindergarten. And they learn that a variety of ways, but they learn that when they are in my care because they get home, they have dinner, they go to bed and essentially their parents play with them on weekends. They don’t spend a lot of hours; I mean, I have kids that get dropped off at 6 a.m. and don’t get picked up until 5:15.

One rural home-based provider indicated that low opinions of providers may stem from the public focus on problems that arise in day care, particularly when children are harmed. The public discourse and, often, policy, respond to the extreme cases, which providers viewed as anomalous:

I would like to have everyone look upon us as professionals in our business because the vast majority of us are, and I’d like them to focus on the positive. Whenever you hear anything about child care, it is always negative, it’s always so-and-so fell in the pool, so-and-so got burned. There are good things going on. Tragedies happen. Accidents happen. I get that. I understand, but we need to focus on the good.

Although most providers saw a need for safety and quality regulation, they rejected what they often saw as policies that stemmed from (and reinforced) a characterization of providers primarily as a risk to be managed rather than as partners in care and education. Several home providers noted rules that limited their ability to shut the door when they went to the bathroom because they were always supposed to have the children in their line of vision. A group of center-based providers noted that when the regulators came, they were not concerned with the care the children were receiving but rather the organizations’ preparation and supplies in case of a natural disaster.

Overwhelmingly, the providers and center administrators with whom we spoke were concerned about the lack of professional respect that child care providers received. Although, as we described above, most providers came to the profession as a result of their attachment to children, many felt that lack of respect for the profession had made it more difficult to provide care. Nearly all providers commented that providers’ contributions to children and society are undervalued, often because people do not understand what providers actually do.

This lack of understanding translates into insufficient funding and policies that are not designed to support providers’ ability to better serve children. One urban center-based provider noted the belief that they are just playing with babies all day:

[W]e’re playing and teaching, which some people don’t get. That's exactly what we do, but I just think, in general, that's a huge issue. Whenever you tell people what you do, it's like, “Oh, early childhood?” It just doesn't get that level of respect, and so I think that's one of the reasons why we don't get the funding or the support or the policies that we really need. The people who make those [policy] decisions, unfortunately, sometimes they do not understand early childhood

Providers, both center directors and home-based providers, throughout the state, wanted child care to be more respected as a profession. As one urban center-based provider succinctly remarked, “I think that's really the crux of all of these issues is respect for the field and the work that we do.” Many believed that lack of respect had led to policies with negative ramifications for the children with whom they worked because it led to the exclusion of their perspectives in policy debates. In the next section, we discuss the kind of support that they believe would result from a more accurate perception of the scope and importance of their work as professional early childhood educators.

6.3 More Resources Are Needed

Providers and center directors throughout the state called for greater resources to support their work as professional educators. Many noted that they themselves needed greater resources for a host of reasons, including safety, compliance with regulations, and a desire to stay abreast of trends in child development. Many also described a need for resources for the children and families for whom they provided care. One urban center-based respondent noted that respect and money often went hand in hand: “While we do the best that we can with very little money, [our work] needs to have a little bit more respect.”

Across all focus groups, respondents made direct connections between funding and their ability to provide professional, high-quality care. In the suburban center-based focus group, respondents reported that they needed funding that was commensurate with the regulatory demands made upon them. Without more financial assistance to programs, particularly those that served low-income children, they were unable to pay providers living wages that matched the skills and education that quality care demands. They saw this as a direct result of a lack of understanding of early childhood education as a public good that supports children and families:

R1: I think that the importance of early childhood education is not at the forefront of anybody’s mind. And I think that has to be something that we have to advocate for. And, having quality programs and servicing the families. It’s not just about the children, it’s the families because they have to work… the only way we’re going to do it is by giving, having quality child care and

R2: And affordable

R1: And affordable

R2: and more support systems in terms of funding supports to do what we really need to do.

Lack of funding was seen as an expression of society’s current assessment of early children education. The following urban center-based provider believed that a shift in funding would only come with a societal recalibration of the value of quality child care.

We need a bigger lift from the community. By community, I mean community dollar, the state, the feds. We need more funding so that families can afford quality child care because quality costs more than just child care, and not just child care, but quality does cost more as we all know. The funding though to support families, if the shift from the policymakers provide[s] funding so that families can afford it, then that means there's a shift in understanding that this work is important.

Another provider who had worked in both preschool and kindergarten noted the lack of public financial support for early education despite the state recommendations for a higher level of education for preschool and prekindergarten (pre-K) teachers. Many of the focus group participants raised this issue, decrying the fact that now that pre-K programming was in the process of being recognized as important and thus better funded and institutionalized, it was being taken out of the hands of early child-care educators and moved into the schools.

When you're looking at what the state is putting out as their recommendations and expectations for a teacher, to have their [Birth-Grade 2 BA] degree, but yet the funding is not there to support the hiring of a teacher in that level to be [comparable] to a school district. (urban center-based provider)

As this quote suggests, funding that could have gone to current early educators working in center- or home-based settings to allow them to “credential up” as required to continue to work with this age group was instead being invested in training of new teachers. Several teachers and a few administrators expressed concern that the advent of free pre-K would limit the number of children in their care and not allow them to continue to cost shift (balance the needs of younger children with higher child-to-provider ratios with those of older children who need less supervision). Providers in all focus groups saw this as a concern because it would funnel children away from child care providers and because it was a missed opportunity to both showcase and increase the value that early childhood educators bring to the table. Still other providers noted specific concerns, such as the availability of resources for children with special needs and English as a second language learners.

Lastly, New York is in the process of gradually raising the minimum wage throughout the state. Many providers noted that this requirement would likely be a challenge for child care facilities that already operate on very thin profit margins. Although all center directors noted wanting to pay their workers more, many were not sure how they could do it. One rural center-based provider said, “I think funding is the biggest concern with minimum wage increasing every year. It is going to be tough.” Others such as those in the suburban center-based group noted that because the minimum wage for fast food workers was rising before that of child care providers, some directors had trouble finding workers because many workers “could just go make some burgers, and [they’d get]... $15, so that, and that’s what most of my teachers did go do.” These concerns, and the way that they were discussed, revealed one of the connections between attracting and keeping qualified and committed child care providers and affordability. Many respondents wanted to raise wages but were stymied by families’ inability to afford higher child care rates. Thus, our respondents sought greater state support through in-kind resources, support for provider credentialing, and funding for tuition for families in need. Many respondents wanted policymakers to have better understanding of their work so that they would provide more public resources to support quality affordable child care while enabling child care providers to make a living wage.

7 Discussion

Our findings are consistent with recent research in the United States which indicates that early child care and education providers are poorly compensated. It adds to this literature by shedding light on the implicit and explicit messages that flow from (and reinforce) dismissive attitudes that cast child care providers as “babysitters” rather than professional educators. This finding is also consistent with other research on other forms of care work such as that of Lisa Dodson and Rebecca Zincavage (2007) who conducted research with aides in nursing homes. Many of the aides went above and beyond and were encouraged to work long hours as a result of making family-like connections with the older adults for whom they cared (Dodson & Zincavage, 2007). In this way, Dodson and Zincavage noted that the nursing home aides were easily exploited financially. The lack of professional respect for care work may be due to the presumptions of what Nancy Folbre refers to as “intrinsic motivation.” In other words, child (and other) care providers are viewed as do-gooders who derive satisfaction from providing care and thus need not be compensated. England and Folbre (1999) noted that because care work is seen as intrinsically rewarding, people are uncomfortable paying for it, and “the belief that love and care are demeaned by commodification may, ironically, lead to low pay for caring labor” (p. 46).

According to England and Folbre (1999), the reason we have publicly supported education is because it is viewed as a public good and society as a whole is considered to benefit from a well-educated workforce and citizenry. The same could and should be said for early childhood education. However, Folbre (2012) underscored the complication of calculating the value of unpaid care. If a competent parent can provide this care, why should it be performed by a highly paid professional? Research on early childhood development over the last 20 years has consistently demonstrated the important impact of early childhood experience on the development of the human brain (Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University, 2016) and on a child’s future outcomes (Heckman et al., 2006). Armenia’s (2009) research with home child care providers found that many sought to improve their status by joining professional organizations and seeking additional training. Similarly, respondents in our study frequently described their own educational credentials and pursuit of training, even though we had not explicitly asked for such information. This is consistent with the push for increasing qualifications and training required by states and advocated by organizations such as the National Association for the Education of Young Children (e.g. Standard 6 of the 10 NAEYC Standards, NAEYC, n.d.).

Our respondents also described the crucial role that they play in supporting families by enabling parental employment and helping during financial crises. In the recent policy discourse on the importance of child care as a work support for parents, this idea has not always been presented. Often the interests of parents and providers are portrayed as competing: parents decry the high cost of care, and providers call for compensation that is commensurate with their skills and the importance of their work. In the absence of societal support for child care provision, the cost of care will continue to be borne by families as a private concern, except in the most extreme cases of poverty. Our research on parents’ perspectives on early child care also underscores its unacknowledged value to families, society, and the workplace (Shdaimah & Palley, 2018). Together with these findings, it suggests that there are opportunities for alliances between parents and providers that center around framing quality child care as a public good, which is how our respondents understand it.

8 Conclusion

The child care providers in this study raised major concerns about their profession. First, they all wanted their work to be recognized as professional. They expressed a universal concern that the profession of early education and care needs to be better respected. Although they wanted greater financial compensation to accompany such respect, they also sought recognition that their work is hard and that most child care providers love and are committed to the children and families they serve. Similar to Tuominen’s (2003) findings in her study of home-based providers, our respondents noted that their work is not simply “babysitting.” Second, many reported a need for greater public financial support for early education and care, noting that most families simply cannot afford to provide their children with quality care and that existing subsidies do not provide enough support for centers or providers to be able to provide quality care. Many families receive no public support, and that leads some mothers to drop out of the workforce. Though the advent of pre-K in New York may make additional funding available for centers that have pre-K programs, it may ultimately mean fewer full-day students for home care providers. Some center-based directors in this study noted that the amount of money they can charge limits the number of providers they can hire in both centers and group home settings. Several providers themselves noted that the reason they went into child care in the first place was because they could not work and afford care for their own children.

If we are serious about supporting early education and care, we must commit resources for child care providers, many of whom would be willing and eager to participate in programs that enhance and grow their early childhood knowledge and skills but cannot currently afford to do so. This is important broadly for the welfare of children, the majority of whom spend time in nonparental child care before age 5. In addition, as noted earlier, the quality of child care affects early brain development. As social workers and advocates of social justice, we need to concern ourselves with the welfare of both child care providers and the children and families they serve.

References

Armenia, S. (2009). More than motherhood: Reasons for becoming a family daycare provider. Journal of Family Issues, 30, 554–574.

Bowen, G. A. (2006). Grounded theory and sensitizing concepts. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 5(3), 1–9.

Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2015). Occupational employment statistics, child care workers. Retrieved from https://www.bls.gov/oes/current/oes399011.htm

Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2016). Employment projections, educational attainment for workers 25 years old and older by detailed occupation. Retrieved from https://www.bls.gov/emp/ep_table_111.htm

Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University. (2016). From best practices to breakthrough impacts: A science-based approach to building a more promising future for young children and families. Retrieved from www.developingchild.harvard.edu.

Dodson, L., & Zincavage, R. M. (2007). ‘It’s like a family’: Caring labor, exploitation, and race in nursing homes. Gender and Society, 21, 905–928.

Duffy, M. (2011). Making care count: A century of gender, race, and paid care work. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Duffy, M., Armenia, A., Stacey, C. & Nelson, M. K. (Eds.). (2015). Caring on the clock: The complexities and contradictions of paid care work. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

England, P., & Folbre, N. (1999). The cost of caring. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 561, 39–51.

Ergas, Y., Jenson, J., & Michel, S. (2017). Reassembling motherhood: Procreation and care in a globalized world. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

Folbre, N., & Project Muse. (2012). For love and money: Care provision in the United States. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation.

Gould, E. (2015). Child care workers aren’t paid enough to make ends meet. Washington, DC: Economic Policy Institute. Retrieved from http://www.epi.org/publication/child-care-workers-arent-paid-enough-to-make-ends-meet/

Heckman, J, Grunewald, R., & Reynolds, A. (2006). The dollars and cents of investing in young children. Review of Agricultural economics, 29(3), 446–493.

Herzenberg, S., Price, M., & Bradley, D. (2005). Losing ground in early childhood education: Declining workforce qualifications in an expanding industry, 1979-2004. Washington, DC: Economic Policy Institute. Retrieved from http://www.epi.org/publication/study_ece_summary/

Hesse-Biber, S. N., & Leavy, P. (2010). The practice of qualitative research (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Hirata, H. (2016). Care work. Sur International Journal on Human Rights, 24(13), 53–63. Retrieved from http://sur.conectas.org/en/care-work/

Krueger, R. A. (2015). Focus groups: A practical guide for applied research (5th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Lanigan, J. (2011). Family child care providers' perspectives regarding effective professional development and their role in the child care system: A qualitative study. Early Childhood Education Journal, 38(6), 399–409.

Laughlin, L. (2013). Who’s minding the kids? Child care arrangements: Spring 2011. Current Population Reports, P70-135. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/prod/2013pubs/p70-135.pdf

Linnan, L., Arandia, G., Bateman, L. A., Vaughn, A., Smith, N., & Ward, D. (2017). The health and working conditions of women employed in child care. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14(3). doi:10.3390/ijerph14030283

Maxwell, J. (2012). Qualitative research design. An interactive approach, (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

National Association for the Education of Young Children. (n.d.). The 10 NAEYC program standards. Retrieved from https://www.naeyc.org/our-work/families/10-naeyc-program-standards

Padgett, D. (2012). Qualitative social work research (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications

Shdaimah, C.S. & Palley, E. (2018). Elusive support for U.S. child care. Community, Work, & Family, 21(1), 53-69.

Shdaimah, C. S., Palley, E., & Miller, A. (2018). Voices of child care providers: An exploratory study of the impact of policy changes. International Journal of Child Care and Education Policy, 12(4). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40723-018-0043-4

Thomas, D. R. (2006). A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data. American Journal of Evaluation, 27(2), 237–246.

Tuominen, M. (2003). We are not babysitters: family care providers redefine work and care. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Whitebook, M., McLean, C., & Austin, L. J. E. (2016). Early Childhood Workforce Index—2016. Berkeley, CA: Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved from http://cscce.berkeley.edu/files/2016/Early-Childhood-Workforce-Index-2016.pdf

World Population Review. (2018). New York Population 2018. Retrieved from http://worldpopulationreview.com/states/new-york-population/

Appendix A

Voices of Child Care Providers: An Exploratory Study on the Impact of Policy Changes. Focus Group Guide

Researcher will introduce herself and thank participants for coming. She will review the consent form and participants will be offered the opportunity to ask questions. If they agree to participate, participants will be asked to sign the form. Those who choose not to participate will be thanked for coming and asked to leave. Researcher will explain that this is a facilitated conversation, and that participants should respond to each other rather than directing their responses to her. She will underscore that she is interested in their experiences and there are no wrong or right answers. She will ask that participants protect each other’s confidentiality.

1. Please introduce yourself and tell the group what the kind of child care you provide, how long you have been a provider, and how you started working in this field (opener)

2. How has your work changed over the course of your career?

3. Are there any policy changes that have impacted your work?

4. Probe: CCDBG, pre-K programs, QRIS

5. What are your greatest challenges as a child care provider?

6. Probe: Personal (i.e. hours, salary)

7. Probe: Professional (i.e. opportunities for growth and development)

8. What supports do you have that facilitate your work? What other supports do you think would be helpful?

9. What are the greatest challenges that face the families you serve?

10. What has been the greatest source of assistance to the families you serve?

11. What would you want policymakers to know about your work as a child care provider?

Final question (go around to each participant): Since you are the experts here, is there anything else that you think that I should know that I haven’t asked?

Researcher will thank the participants for their time and ask them to please contact me with any questions or concerns that arise, reminding them that my contact information is on the copy of the informed consent form that they received at the beginning.

Author´s Address:

Elizabeth Palley, JD, PhD, MSW

Adelphi University School of Social Work

1 South Avenue, Garden City NY 11530-0701

phone: 516-877-4441

email : palley@adelphi.edu

Author´s Address:

Corey S. Shdainah, PhD, LLM

University of Maryland School of Social Work

525 W. Redwood St., Baltimore Maryland 21201

410-706-7544

cshdaimah@ssw.umaryland.edu