Towards a Typology of Social Work Assessments: Developing practice in Malaysia, Nepal, United Kingdom and Vietnam

Jonathan Parker, Bournemouth University, UK

Sara Ashencaen Crabtree, Bournemouth University, UK

Azlinda Azman, Universiti Sains Malaysia

Bala Raju Nikku, Universiti Sains Malaysia

Uyen Thi Tung Nguyen, Victoria University College, Yangon, Myanmar

1 Introduction

Social work assessment represents a ubiquitous, although differentiated, activity across the world. Assessments are carried out or completed in many forms, with diverse groups of social work service users or clients, and are undertaken for different purposes. Assessments may be confused with evaluation but they are ‘more akin to an exploratory study which forms the basis for decision-making and action’ (Coulshed & Orme, 2006, p. 26). Describing social work assessment as ‘a focused collation, analysis and synthesis of relevant collected data pertaining to the presenting problem and identified needs’ (Parker & Bradley, 2014, p. 17), portrays it as purposeful and professional filling the interstices of complex human lives with tasks designed to populate a planned social work process. Assessments such as these may also be driven by social regulatory frameworks, spoken or unspoken, and promulgate governmental or received societal norms at a practice level. They may also be led by different disciplinary approaches or political purposes such as helping at individual or community levels, forming various plans for action, and even promoting praxis by participatory involvement.

This paper explores some meanings identified for and by social work assessment, and introduces an explanatory model to consider the development of social work assessment in Malaysia, Nepal, Vietnam and the UK. Understanding what social workers are doing is critical to the moral foundations of practice, and this model allows social workers potentially to locate assessment tasks and functions in the socio-political contexts in which they are undertaken. A sociological model of isomorphic convergence is employed to understand some of the reasons social workers and their organisations practise in these ways. Reflexivity and self-critical analysis offers possibilities for ethical practice.

2 Background and context

Social work assessments are complex. They have been described as the cornerstone of good social work practice (McDonald, 2006; Parker, 2013). However, this positive view does not allow for the various ways in which they may be conducted or the purposes to which they may be put. It is important to critique the moral purposes underpinning assessments, and dangerous simply to undertake a social work assessment because of unquestioning custom and practice within a particular organisation or with a specific client group.

Assessments in social work serve different purposes. They weigh and evaluate settings, circumstances, people and/or events. However, they do so as part of a broader discourse of need, power and values, often reflecting a presumed or possible legitimacy or illegitimacy of those assessed. Assessments can result in a tangible report that takes a ‘snapshot’ of a situation, and can stop at that juncture. They can also be continuous and run alongside social work undertaken with people, groups and communities, even being participatory with those groups or individuals setting the agenda and performing the functions of assessment.

However they are undertaken, social work assessments are purposeful and discourse-laden representations of knowledge about an observed subject. They are designed to guide future interactions between the observers and the observed in order to achieve certain assumed benefits or states. It is incumbent upon social workers to practise according to agreed and accepted values. In order to do so, self-reflective critique of practice is fundamental.

Because of the ecological, social and political contexts in which social work assessments are undertaken and the many purposes to which they are put, all forms of assessment practice run the risk of inducing normative behaviour: following the rules prescriptively as though they represent unquestionable ‘givens’. Therefore, social work assessments need to be ‘troubled’ or subject to critical analysis. It is important that assessment is not seen simply as an activity, skill or practice that can be undertaken in a linear fashion, moving from ‘A’ to ‘B’ without recognition of theoretical and ideological underpinnings, and the importance of working together with people who use social work services (Hepworth et al., 2009; Parker, 2015).

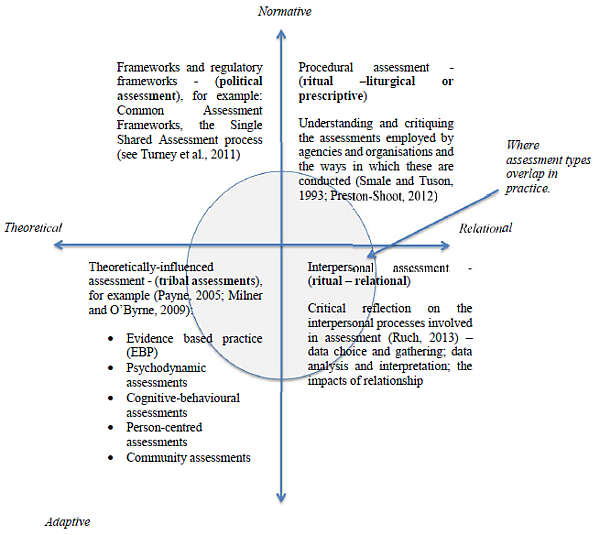

Grouping social work assessments around particular purposes can help develop a deep critical appreciation of the ways in which assessment are understood. It can also illuminate the meanings constructed in the acts of assessment and identify impacts that assessment may have on individuals. The following model clusters social work assessments around the following types: prescribed and political approaches, ‘tribal’ allegiances fostered by theoretical ideologies, and processes or rituals involved in the ‘dance’ or inter-relational conduct of assessment (Parker & Bradley, 2014; Parker, 2015) (see figure 1).

3 Assessment morphologies

Whilst social work assessments of people’s circumstances and needs are, to a greater or lesser extent, politically or ideologically determined, prescribed and driven, it is possible for individual social workers to engage as human-to-human with individuals, to recognise their own theoretical and personal biases rather than to simply ‘apply’ a technical and impersonal assessment. Fostering a critically reflective approach to assessment is central in this regard. Assessments move from being theoretically-driven to those that are more fluid and dependent upon the relationship forged between assessor and assessed, and oscillate between normative and prescribed approaches to those that are adaptive to context. In practice, social work assessments may take elements from all such heuristically identified parts, but it is important to understand where the assessment undertaken sits in this model so that it can be subjected to reflective critique by the social workers undertaking them (Parker & Bradley, 2014).

Politically-driven assessments operate as a means of grouping people around a variety of socio-moral types – people in need, people abused or abusing, drug and substance users. These ‘types’ are often predicated on an assumed and unspoken deficit model of social work in which practitioners work to offset or complete something lacking in the lives of service users. Whilst suggesting governmentally-prescribed practices, these political drivers are not necessarily macro-level ones. The politics of social work organisations, local communities and those operating at interpersonal levels also prescribe the models and frameworks for social work assessment and also regulate access to services through the application of particular moral lenses. Political social work assessment frameworks, however, are generally built around a particular theory favoured by contemporary political authorities and as such are normative (Parker, 2015).

Examples of this kind of assessment range from those developed within government departments that seek to standardise services, or to regulate and control, whilst often purporting to enhance the behaviours and lifestyles of certain groups, such as parents, young offenders, people with mental health or capacity problems. Such assessments, such as those relating to child protection, are increasingly common in the UK and the Global North, but synergies with systems elsewhere in the world lead to adaptation and potential adoption elsewhere. This mimetic standardisation may be left unchallenged with the relational and social justice aspects of social work being subsumed under a normative political hegemony.

Theoretical assessments represent a mezzo-political level, being driven by a disciplinary allegiance that can almost become tribal and sharply distinct, such as practitioners subscribing to cognitive-behavioural approaches and those following psychodynamic theories (Sheldon & MacDonald, 2009), or focusing on individual casework rather than community development approaches (Parker, 2013). These approaches differ from macro-political ones being usually more adaptive to context and specific needs and more open to individual service users requesting or refusing services on the basis of a particular school of practice or discipline. However, there is a potential danger of excluding the interpersonal aspects necessary to promoting human change and development by rigid subscription to one particular model of practice. This creates a demand for constant reflexivity in social workers undertaking assessments that follow specific theoretical approaches.

There is a difference drawn between liturgy and ritual. Liturgy relates to the prescribed words that are used within a context, usually religious, that lead people along familiar pathways in worship and faith, whilst rituals concern the behavioural practices engaged in and often accompanied by the spoken liturgy. They are distinct concepts but the two overlap. In this example, the ritual-liturgical perspective represents a formalised approach to assessment in which organisational pro forma or checklists are applied to achieve a certain perceived end, somewhat akin to procedural assessments (Smale & Tuson, 1993). These assessments concern the recitation of agreed set of words or service offers, according to an objectified structure that is believed to impose order and provide equality of treatment. Examples include prescribed assessment tools employed in child development, mental health and care management social work. As with the theoretical assessment approach the individual may be excluded and the following of procedures and processes become an end in itself as appears to have happened in much UK social work (Munro, 2011).

The ritual-relational approaches to assessment move towards a more visceral engagement between human beings in which relationship takes the foreground and the interplay of social work knowledge (theory) and practical helping (action) enact a ritualised performance of humanising the ecological conditions in which social work is practised (see Bell, 2009/1991). This approach moves the social worker from employee to professional/inter-relational. It corresponds to Smale and Tuson’s (1993) exchange relationship and draws from Martin Buber’s (1933) exploration of Ich und Du – a meeting of I and Thou - as necessary in any human relationship. Undertaking social work assessment in such a way as to engage relationally first may put social workers in conflict with hierarchies and formal organisations whilst, crucially, it champions human rights and social justice.

Assessment models may not fit neatly into any one of these four models and political and tribal assessments may be relational as well as theoretical, whilst the political and ritually-procedural may be more adaptive in certain contexts. However, the four quadrants offer a means of analysis for social work assessment that can help identify the purposes and consequences in using particular approaches to assessment (see figure 1). Depending on how this knowledge is used it can assist social workers in reflecting on the values underpinning their practices. It can also assist in identifying for what purpose and for whom social work assessment serves, allowing practitioners to set the service user/client centre stage and to highlight those purposes which work against them.

3.1 Global understandings of social work

The ritual of conducting a social work assessment is enacted within the schema of shared cultural assumptions of service ideology and delivery. In respect of socio-religio-cultural diversity the focus, practice and outcome of assessment will differ widely across international contexts that recognise, however loosely, this form of vocational/professional ritual. In her examination of social work practica in the United Arab Emirates, Ashencaen Crabtree (2008) considers the practice limitations experienced by Emirati students working with service users due to a serious knowledge deficit established in the curriculum owing to religio-cultural censorship of sensitive material relating to sexuality and sexual abuse; otherwise regarded as mainstream content for social work students in the Global North, for example.

Culture as socio-ethno-diversity, together with the wider and clustered sociological/anthropological concepts of ‘culture’, acts, arguably, as the main informant of the nexus of social work practice in national and regional contexts. This, however, remains permeable to the influences of dominant cultural forms across the globe, as indeed is the basis of Midgeley’s (1981) seminal critique of the imperialism of ‘Western’ social work in developing nations that has latterly yielded to the rise of indigenous and authenticised forms of social work that will include localised assessment models (Ashencaen Crabtree, 2008; Ling, 2007).

Social work assessments are, therefore, influenced greatly by setting and culture. A good anecdotal example of an assumed indigenised social work assessment was serendipitously offered to the second author by an NGO in Malaysia during the writing of this paper. This agency sought assistance in refining their assessment processes. A consequent examination of documentation revealed a case where the environmental context of service users was reported by a practitioner to be haunted by spirits. Accordingly (and arguably, logically) the assessment of need identified, among other items, the need for intervention by a ‘ghost-buster’. While perhaps this would be viewed as a somewhat unconventional assessment in many countries, addressing wide-spread beliefs in supernatural and harmful agencies/entities may be entirely compatible with relevant knowledge for local practitioners if this represents shared cultural beliefs embracing both service users and social workers. The assessment process itself, however, shares aspects across the types identified above in being driven by accepted theory, employing specific forms of language and developing through relationship-building.

Ashencaen Crabtree et al. (2008) illustrate another culturally accepted explanation concerning the malign, supernatural possession of a troubled Arab social work student that contrasted sharply with alternative and more familiar explanations involving the ritual reading of signs and portents as psychodynamic liturgy.

Indigenous models emerging from the margins of dominant social work discourse, carry the clear potential to both challenge and enrich established social work doctrines towards a more faceted and nuanced, globally relevant morphology (Ashencaen Crabtree et al., 2008). However, a preoccupation with ‘professionalisation’ of social work education and practice (Baba et al., 2011) tends to locate itself on a continuum that stands at some distance from causal explanations, as described above. In this way, to assess ‘professionally’ may involve adopting another viewpoint, that of the dominant discourse, and of disowning the localised, cultural and/or indigenous. Ashencaen Crabtree (2012), following Suman Fernando, has written extensively on the cultural dislocations of applying professionalised and legitimised aetiologies that are disconnected from the cultural context of the client/service user and frequently the practitioner themselves.

The political context where social work is practised nationally is hugely influential in deciding national priorities of need, definitions of need, the identification of people as ‘needy’ and maybe ‘deserving of need’, together with legitimated forms of assessment and intervention by mandated groups. This equally serves to define illegitimate practice, ineligibility for services, and the illegitimate practitioner manqué.

Commensurately, and in recognition of the greatly diverse context in which social work is practised (Hugman, 2008), there has been considerable labour involved in attempting to draw together the distinctive features of international diversified social work, in order to delineate a commonly recognised professional ‘profile’, defined through agreed global definitions and values. This task undertaken by the International Federation of Social Work (IFSW), and supported by the International Association of Schools of Social Work and other bodies, is conceivably Herculean in scale in seeking identified commonalities across such heterogeneous forms of human services delivery.

To this end, it is instructive to consider the complex socio-political semantics of some of the terms used to articulate these identified commonalities as found on the IFSW website: ‘promotion of social change’ ‘empowerment’ ‘human rights’ ‘social justice’, ‘liberate’ ‘vulnerable and oppressed’ ‘social inclusion’. All are open to multiple nuances and interpretations, and while that is obviously acknowledged and embraced by the IFSW as overtly inclusive, one practitioner’s conceptualisation of ‘empowerment’ or ‘vulnerability’ may be equally viewed as another’s exercise of oppression (Parker et al., 2014), thus rendering the assumed commonalities problematic and open to contestation.

3.2 Neo-institutional analysis and isomorphic convergence

As a means of understanding and theorising political, tribal and ritualised assessment practices, isomorphic convergence provides a model, drawn from organisational sociology (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983), suggesting movement towards homogenisation in assessment representing a means of ensuring legitimacy in practice and reducing the risks of blame and complaint from politicians or an unhappy public when tragedies occur, or from disgruntled clients who compare differential treatment in practice (Parker & Ashencaen Crabtree, 2011). Globalisation, as discussed above, has led to these convergences being applied almost ubiquitously, albeit taking into account local differences to an extent. Convergences may be understood as coercive by the passing and implementation of legislation, policies and procedures that prescribe practices; mimetic in doing that which other social work organisations do, and normative in terms of an uncritical acceptance of contemporary hegemonic discourses in social work thought and practice across the world (Dingwall, 2008). In analysing social work assessment across countries it is imperative to keep in mind the ways in which legitimacy is conferred and sought, and to act as a critical exegete in respect of the outcomes of these processes. As with any model, we need to treat this with caution; as Beckert (2010) argues the processes of convergence can also lead to divergence; and this perhaps is where the potential for change and development can be realised with more appropriate approaches and resistance being promoted in social work assessment.

4 Study and methods

Data were collected concerning some of the core types of social work assessment in each country. These data were gathered in 2014 from a range of sources: interviews with social work practitioners in each country (n=12), from social work agencies, and from policy data. This provided a rounded perspective. No personal or service user data were collected. It was not possible to be too rigid in respect of inclusion and exclusion criteria for data collection because of country differences between social work policy and practice, in addition to variation of national social work development and differing assessment practices in the local context. Existing pro forma or prescribed assessments were sought as were views of existing practitioners relating to daily practices. These assessment types were set within a brief context of social work within each country to ensure local practices could be understood, as could drivers for change.

Methodologically, a question is raised as to why these four countries are being considered. A core reason was pragmatism, given that the authors, either from or with experience in each of the countries in the study were working together, at that time, in a university in Malaysia and comparison of different social work approaches formed a central plank of discussion. It was also considered important that the countries are Asian except the UK; however, Malaysia and the UK are linked by a colonial past, whilst Britain and Nepal are linked historically through the British-Indian colonial period and British East India Company alongside signing the 1923 Treaty of Friendship and Perpetual Peace. Vietnam is a little different in this regard but is part of Southeast Asia and also has a colonial history, albeit French. All four countries have experienced recent internal civil strife and social welfare/social work tends to develop further within the context of civil unrest (Ashencaen Crabtree et al., 2012).

5 Assessment types in the four countries

5.1 Assessment in Malaysia

Social work practice was first introduced in Malaya during British colonialism with the establishment of the Social Services Department in 1912. The primary purpose of the department was to improve the wellbeing of migrant labourers (Baba, 1992). In the early 1930s, the department closed due to the global fiscal depression, but was later re-established in 1937 within the Colonial Office to provide social services to the communities. This marked the beginning of a more structured social welfare system in Malaya (Mair, 1944). Today, Malaysia’s welfare services and programmes are primarily offered by the Department of Social Welfare (DSW), with the support of the many non-governmental organizations (NGOs). In fact, the rationale and purpose of the establishment of NGOs were to complement and supplement the role of DSW in providing social welfare services due to increasing social issues throughout the country. It is the employees of DSW and the relevant NGOs, who have become the main providers of social services, assuming the role of social workers in contemporary Malaysia.

Social work as a profession in Malaysia is not as well recognised as it is in many developed countries. The recruitment of non-qualified social workers, without formal social work education is common with only one out of 10 social workers being formally educated for the role (Tan, 2007). Many of these social workers practise directly with rape victims, women and children experiencing domestic violence, juvenile delinquents, child protection, disabled people, older people and other ‘vulnerable’ groups in the population. Assessment is generally completed as a precursor to intervention and aligns with theoretical-tribal and ritual-liturgical approaches driven by the agency rather than by particular standardised approaches directed by government. How comprehensive and accurate these assessments are is open to question because they are driven by singular agency interests. Unfortunately, there is no research available to-date on the assessment practices of these unqualified social workers in Malaysian social services settings, reflecting the nascent professionalism within social work.

In Malaysia, methods of assessment are primarily based on the criteria set by specific agencies. The nearest example to a politically-driven standardised assessment is undertaken by the DSW, which uses specific prescribed forms and methods for completing individual, family and community assessments, including preparation of Social Reports, Probation Reports, Protection Reports and Progress Reports. From interviews with four social workers from the DSW the preparation of these reports were based on social workers’ own interpretations from face-to-face interviews with clients, observation and home visits. This may suggest also a degree of relationship informing the development of models, although prescription underpinned the approach. So, in practice-related terms there is recognition of the relational but also a turn towards the ritually-liturgical or procedural and, given its ministry position in government, the beginnings of politically ordained professional standards.

Similarly, the NGOs use their own methods of assessment based on understandings and knowledge acquired at various training programmes which inculcate adherence to certain processes and forms of assessment (interviews with three NGO practitioners). In summary, no matter what and how assessment is conducted, the majority of the agencies conduct assessment to enable some form of documentation about the history and development of intervention towards clients, following a ritual-liturgical rather than a theoretically-driven model. The guidelines for assessments rely heavily on practitioners’ values and perceptions, custom and practice of the agencies, and based on training undertaken.

Conducting assessments raises questions and dilemmas for Malaysian social work. There is, as we note, no standardised political form of assessment used for any specific client groups and many disparate agencies often rely on existing unqualified social work staff to carry out assessments based on the agency’s aims. Also, a level of confusion exists between professional social work and voluntary work by service providers and the general public, which has resulted in different understandings of what constitute appropriate assessments.

Changing attitudes in favour of ‘professionalising’ social work highlights a key challenge for Malaysia in providing the best assessment when working with clients. To achieve this change a normative approach is being introduced within universities to ensure that social work curricula employ real case vignettes to enhance social work students’ skills and competency in theoretically-driven assessments.

The DSW, professional associations and academies in Malaysia are seeking to develop a more standardised political social work assessment. However, there is no policy setting minimum standards of assessment for providing effective and quality services to clients and the professionalisation of social work profession remains at an early stage.

5.2 Assessment in Nepal

Nepalese social work educators and practitioners agree that assessment is a core feature of social work practice, the essence of social work intervention. Whilst it is recognised that competence and skills in assessment should be one of the formal requirements for graduation in social work from any university in Nepal, the development of social work education and practice in this post-conflict, transition-led country is nascent and struggling to form its identity and legitimacy in society (Nikku, 2012). There is, like Malaysia, currently no politically-prescribed form of assessment for social work.

Nepalese social work education is relatively young and inchoate. It was only in 1996 that the first department of social work at Kathmandu University began and almost all colleges providing social work are located in Kathmandu, the capital city, resulting in restricted access to social work education for students from poor and disadvantaged rural areas of Nepal. The title ‘social worker’ is rather loosely used and, consequently, may be abused: anyone in a social service agency can claim that they are doing social work (Nikku, 2010).

Social work colleagues at the Nepal School of Social Work (NSSW), consulted for the purpose of this paper, agreed that professional assessment skills are required to become a reflexive social worker. They also indicated that appropriate curricula inputs should be included to strengthen further social work education in Nepal. However, in practice assessment forms and practices vary widely and there is a lack of coherent politically-driven understanding of what constitutes social work assessment, how theoretically it should be conducted and what roles qualified social workers should play as agency representative in a ritual-liturgical way or by forming a relationship with service users first and foremost. There was a concern for relational approaches and colleagues stated that social work assessment should not burden or dehumanise clients but should be an intentionally rational and systematic process to discover client strengths and help people to overcome their limitations. The assessor’s role should not be a gatekeeping one but a facilitating and empowering one. The process should be based on insightful encounters and open sharing in a trusted environment between professional social workers and clients. This suggests that ideal-type assessments reflecting theoretical and professionalised procedures are recognised as the way forward although not yet achieved.

The social work educators interviewed are aware of new models of assessment from global connections, such as user-led, or client-centred, approaches where it is not the social worker who makes the decisions or holds the power and wish to teach these models (Wenglinsky, 2000). However, a mismatch between practices and these new models of assessment mean their wishes remain aspirational at present. According to one educator at NSSW:

“There are more than 30,000 non-governmental organisations registered with Social Welfare Council of Nepal. Not even 1% of the staff working for these organisations are trained in social work but many of them are involved in assessment and taking crucial decisions about clients they cover under different programmes. This situation is worrying as the carer’s decisions about clients depends upon the way the needs are assessed and this assessment is influenced by a host of factors like education, level of skills, legal and political understanding of the carer to name a few. There is a great need for strengths-based social work assessments in schools, hospitals, juvenile homes, orphan care centres, old age homes and in many government and non-government agencies dealing with human services in Nepal. The urgency is to train social work faculty so that they can impart right assessment tools and conceptual framework to their students in the classroom.”

The case of Nepal provides evidence about the drive towards convergence in models of assessment where social work education and practice seek to ‘professionalise’ and become embedded within the socio-political fabric of countries.

5.3 Assessment in England, UK

Social work differs slightly across the four countries or administrations comprising the UK. For the purposes of this paper the focus will be on social work assessment in England. Social work is long established in the UK although its credentials as a profession continue to be debated (Parker & Doel, 2013), as do its historical roots (Payne, 2005). It is also the case that continued reform and revision of education and practice over the last five decades has reshaped social work in ways that influence official pronouncements about its characteristics, value and the quotidian practices of social workers.

Social work is entrenched, predominantly, within the local government systems of England and Wales and therefore represents, to an extent, a political means of organising welfare, social and interpersonal relations in society. However, moves to outsource or privatise social work practices to voluntary and for-profit agencies are being actively considered. Government departments regulate and control practices through policy and prescribed practices, especially in childcare and child protection work, the assessment of adults in need and in respect of mental health, which has lead to the development and deployment of assessment tools and frameworks prescribing practice. These prescribed practices reflect hegemonic political ideologies, which require critique and understanding in this context (Clifford, 1998). For instance, the Department of Health (2000) published the Framework for Assessment of Children and Families. The Framework specified the ecological systems theoretical approach and from this specified the domains of assessment to be considered. This was followed in the Working Together guidelines to include timescales for assessments and an auditable system that imposed great pressures on social workers (HM Government, 2013a), and driven by legislation (HM Government, 2013b). Mental health assessment is also channelled by the legislation to cover core questions of the nature and degree of a person’s mental health problem, whether it ‘warrants’ detention and for what purpose; single shared assessments for adults collate social data, physical and mental health information relating to needs that should be shared across relevant human service agencies. When making assessments of young people who offend, an assessment of their assets is made to determine needs and interventions to prevent further criminal activity.

These assessments represent the characteristics of those promoting their use and are driven by contemporary politics of social life, responding to popular protest and perception rather than identified needs. Often, they follow a liturgy set by the creators of such assessments, that is, a form of words and areas to follow and examine that demonstrate some of the assumptions underpinning them. This underpinning is not necessarily problematic and adding a structure and degree of standardised expectation to social work assessments can provide safety in practice. However, the ways in which assessments are implemented depends to a large extent on the social workers themselves, notwithstanding time and employer pressures. Questions of values and the need to start from the individual being assessed are clear. Relationships are seen as central to the process but this can be instrumental in simply assisting the data collection itself which may help the agency but not necessarily the person. Relationships can be seen as a human act through which a social worker engages directly with another human being affirming the other’s humanity.

Academic social work literature concerning assessment in the UK focuses on the person-to-person activity that engages people in determining their lives and choices as far as that is possible and permissible depending on the context in which such assessments take place (Middleton, 1997; Milner & O’Byrne, 2009; Martin, 2010). So, in essence there is a convergence of the formal and the personal, the prescribed and the fluid. In order to ensure that the person remains best served by social work assessment practitioners must seek understanding of what is driving the process and how that aligns with professional ethics and values, challenging their own practices when these diverge, either with the prescribed process or the values of the profession. In this dialectic process, social workers can construct new more appropriate forms of assessment, so important in the multi-ethnic, multi-faith composition of the UK. How this is adopted into daily practices and understandings will come through the sharing and publication of research and continued engagement with the political authorities concerned with social work and social welfare.

Recognition that social work, including assessment, is a political and politicised process characterises UK social work. It offers opportunities for the inclusion of the person at the heart of the process, as argued for in Munro’s review of childcare social work (Munro, 2011) or in respect of adults in the Care Act 2014, but it also brings forth dangers of over-prescription and rigidity that exclude those being assessed (Platt et al., 2011). It also seems to be one of the Western models that is seen as emblematic of a ‘good’ and professional model assessment to follow.

5.4 Assessment in Vietnam

Social work in Vietnam has its roots in religious charitable institutions influenced, predominantly, by French social work (Kelly, 2003, Durst et al., 2006). The strong French influence, especially in Southern regions, was criticised as ineffective, unsustainable and paternalistic, failing to lead to client empowerment (Kelly, 2003, Durst et al., 2006). Political conflicts in the country, however, meant that social work could not fully develop as a profession, although it has been practised for decades in the areas of ‘institutional care models for orphanages and care homes for the elderly and persons with disabilities’ by Catholic missionaries (Durst et.al, 2006).

Social work continued its nascent role of helping in the Vietnamese community during the post war years although social work itself was not recognised as a profession in the country (Barnes & Newfield, 2008). Vietnam introduced modern economic reforms in 1986 encouraging economic growth. This economic growth requires strong a social work education and profession to address identified social issues and problems in Vietnam.

There has been a dramatic change in social work, which is now accepted as a profession in government, and institutions of higher education (HEIs) are starting to offer social work education programmes. The Women’s Studies programme at the Open University in Ho Chi Minh City established a social work minor in 1992. In 2004, social work was finally recognised as a major academic field: HEIs in Vietnam could begin social work programmes. Whilst at first, they lacked trained faculty, field placements, and textbooks there are now more than 30 social work programmes in Vietnam offering undergraduate degrees, although as yet no postgraduate degrees are offered. Barnes and Newfield (2008) have estimated that only 50 to 60 people hold MSW degrees in a country of 85 million people.

There is no standard politically or theoretically driven assessment model in Vietnamese social work. Each NGO, International NGO (INGO), or governmental social welfare department has its own criteria and methods for conducting assessments and generally demands a ritual-liturgical approach that is underpinned by specific agency discourses as opposed to clear standardised political or theoretically-driven approaches. Also, assessment is not formally taught on professional courses and assessment skills are mainly gained through personal experience in the field, through short-term training courses or invited training sessions from experienced resource persons in more wealthy organisations.

Based on data from different Vietnamese NGOs, assessments, currently, can be grouped into three categories:

1. Basic - which is usually implemented by small-scale NGOs. An agency receives a referral, sends staff to do home visit to an individual or community and the social worker puts a written note directly on the referral form indicating whether the request is approved or not – a ritual-liturgical response.

2. Semi-Assessment - agencies develop, in-house, a simple form for assessment, asking basic information about the clients and their family background, their household conditions, their income level, again a ritual-liturgical response.

3. Professional assessment - detailing information concerning all five capitals (human, social, environmental, physical, financial). Here, social workers are trained to do assessments which are usually practised in big and well-known INGOs such as World Vision, UNDP, and UNICEF and combines political and ritual-liturgical approaches, whilst sometimes bringing in theoretical models to justify data collection, but they are driven from external agencies to the Vietnamese government.

The lack of standard social work assessments in Vietnam has been seen as problematic in the light of the Vietnamese government strategy for wide-scale social work development. However, different communities, locations, social statuses, social issues and problems may require different assessment methodologies and strategies in social work and it is argued that standardised assessment should not be rigidified but remain flexible.

6 Discussion: meanings of social work assessments

The lack of standardised approaches and evidence of the use of personal/individual judgement and values in assessment, and through unspoken NGO practices, in Vietnam, Nepal and Malaysia is somewhat decried. On the other hand, in the UK it is considered there may be a problem of too much standardisation and not enough focus on professional judgement and values (Doel, forthcoming). To an extent one might interpret this as a problem of isomorphic convergence: an unspoken belief that to standardise assessment according to, predominantly, Western models will offer a more professional, safe and better practice; that it represents an unquestioned good rather than being critiqued and authenticised within indigenous contexts (Ling, 2007; Parker et al., 2014). It is clear that social work, internationally, must guard against the assumption of accepted givens if it is to provide an appropriate service to people locally, whilst adopting and adapting, through reflective questioning, well developed elements of assessment practice from other countries in which social work may be more established. It is also important to remember that convergence around similar forms of practice need not rigidify but can accommodate indigenous features and synthesise appropriate local practices. It can be a dialectic rather than linear process.

When considering assessment practices against the four quadrants of the model it is clear that all four countries either employ, in the case of the UK, or are seeking to develop a political approach to assessment at a range of levels macro and organisational. The dangers of this drive towards standards and prescription need to be acknowledged in terms of ‘fit’ to the indigenous situations of each country and in respect of what is left out or ignored when assessment domains are set. The lack of standardised processes, however, allows tribal or theoretically driven assessments to permeate NGOs within each country, depending on which ‘tribe’ or theory is in the ascendency at the time. It is interesting that theoretical approaches were mostly lacking from the discussion of assessment within each country, perhaps suggesting either that inductive developments are contemplated, that social work education is lacking in this regard or that the focus on process and form have relegated theory in the search for professional legitimacy.

Ritual/liturgical approaches had been developed on an ad hoc basis by NGOs in Nepal and Vietnam in which certain assessment elements were developed into pro forma to collect relevant data but these were inconsistent and seemed to lack theoretical underpinnings.

Ritual/relational approaches were in evidence in respect of values expressed in each country and were considered problematic where these were undertaken without an overall assessment strategy, format or theoretical base; or indeed applied without an educational background in social work. However, the need for these approaches to ensure ecological and indigenous authenticity is paramount.

The model of social work assessment we introduced is, we believe, helpful as a heuristic device and as a means of helping social workers to question what they are doing in respect of their assessments, what values underpin their work and what motivations drive them. Indeed, all four countries consider a focus on values to be important especially in terms of engagement with people in their ecological contexts. Identifying explicitly the four approaches to assessment can ensure that a personal focus is maintained when assessments are mandated and, most importantly, allow social workers to scrutinise the meanings their assessments are constructing for them, their agencies, for social work as a profession and, most importantly for the people with whom they are practising.

It is important that learning and teaching about assessment, developing a critically reflexive approach that questions continuously at all levels, making clear what assessment is about informs social work education and training. From this social workers can locate their value bases and ensure that these and indigenous exigencies are met. It is also important that the potential adoption of hegemonic assessment practices, which may imply a search for legitimacy and professionalism, are critiqued in a way that allows for the development of appropriate synthetic assessment models for each country. The sharing of these internationally allows for a continuous dialectic process that responds to change and need as it arises.

References:

Ashencaen Crabtree, S. (2012). A Rainforest Asylum: The enduring legacy of colonial psychiatric care in Malaysia. London: Whiting & Birch.

Ashencaen Crabtree, S., Parker, J. & Azman, A. (eds) (2012). The Cup, the Gun and the Crescent: Social welfare and civil unrest in Muslim societies. London: Whiting & Birch.

Ashencaen Crabtree, S. (2008). Dilemmas in International Social Work Education in the United Arab Emirates: Islam, Localization and Social Need. Social Work Education, 27(5), 536–548.

Ashencaen Crabtree, S., Husain, F. & Spalek, B. (2008). Islam & Social Work: Debating values and transforming practice. Bristol: Policy Press.

Baba, I., Ashencaen Crabtree, S. & Parker, J., (2011). Future indicative, past imperfect: a cross cultural comparison of social work education in Malaysia and England. In S. Stanley (Ed.), Social Work Education in Countries of the East: Issues and Challenges (pp. 276-301). New York: Nova.

Baba, I. (1992). Social work: An effort towards building a caring society. In C. K. Sin & I. M. Salleh (Eds.), Caring society: Emerging issues and future directions (pp. 509–529). Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: ISIS.

Barnes, A. & Newfield, N. (2008). Reinstituting Social Work in Vietnam. Social Work Today, 8(6) Retrieved June 2014 from http://www.socialworktoday.com/news/psw_110108.shtml.

Beckert, J. (2010). Institutional Isomorphism Revisited: Convergence and Divergence in Institutional Change, Sociological Theory. 28(2), 150-166.

Bell, C. (2009/1991). Ritual Theory, Ritual Practice. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bisman, C. D. (2001). Teaching Social Work's Bio-Psycho-Social Assessment. Journal of Teaching in Social Work, 21(3/4), 75-89. DOI: 10.1300/J067v21n03_07.

Clifford, D. (1998). Social Assessment Theory and Practice: A multi-disciplinary framework. Aldershot: Ashgate.

Coulshed, V. & Orme, J. (2006). Social Work Practice: An introduction. (4th ed.) Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Department of Health (2002). The Single Assessment Process Guidance for Local Implementation and Annexes (HSC 2002/001; LAC (2002)1). Retrieved Oct 2013 from www.dh.gov.uk/policyandguidance.

Department of Health, Department for Education and Employment, Home Office (2000). Framework for the Assessment of Children in Need and their Families. London: The Stationery Office.

DiMaggio, P. J. & Powell, W. (1983). "The iron cage revisited" institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields, American Sociological Review, 48(1), 147-60.

Dingwall, R. (2008). The Ethical Case against Ethical Regulation in Humanities and Social Science Research, 21st Century Society, 3(1), pp. 1-13.

Doel, M. (forthcoming). Rights and Wrongs in Social Work: Ethical and practice dilemmas. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Durst, N. (2006). An Analysis of Social Work Education and Practice in Vietnam and Canada. Regina, Canada: Social Policy Research Unit (SPR) Faculty of Social Work University of Regina.

Hepworth, D., Rooney, R., Rooney, G., Strom-Gottfried, K. & Larsen, J. (2009). Direct Social Work Practice: Theory and Skills, (8th ed.), Belmont, CA.: Brooks Cole.

HM Government (2013). Working Together to Safeguard Children: A guide to inter-agency working to safeguard and promote the welfare of children, Retrieved October 2013 from http://media.education.gov.uk/assets/files/pdf/w/working%20together.pdf

HM Government (2013). The Care Bill explained including a response to consultations, pre-legislative scrutiny on the Draft Care and Support Bill Cm 8627, London: The Stationery Office.

Hugman, R. (2008). Ethics in a World of Differences, Ethics and Social Welfare 2(2), 118–32.

International Federation of Social Work (IFSW) (2001). Definition of Social Work. Retrieved May 2014 from http://ifsw.org/policies/definition-of-social-work/

International Federation of Social Work (IFSW) (2000/2013). Update on the review process of the Definition of Social Work. Retrieved May 2014 from http://ifsw.org/news/update-on-the-review-process-of-the-definition-of-social-work/.

Kelly, P. F. (2003). Reflection on Social Work Development in Vietnam. Hanoi, Vietnam: National Political Publisher.

Ling, H. K. (2007). Indigenising Social Work: Research and practice in Sarawak, Selangor: SIRD.

Mair, L. P. (1944). Welfare in the British colonies. London: The Broadwater Press.

Martin, R. (2010). Social Work Assessment, London: Sage/Learning Matters.

McDonald, A. (2006). Understanding Community Care: A guide for social workers. (2nd ed.). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Middleton, L. (1997). The Art of Assessment. Birmingham: Venture Press.

Midgeley, J. (1981). Professional Imperialism: Social Work in the Third World. London: Heinemann.

Milner, J & O’Byrne, P (2009). Assessment in Social Work (3rd ed.). Basingstoke: Palgrave.

Munro, E. (2011). The Munro Review of Child Protection: Final Report, a Child Centred Approach Retrieved June 2012 from http://www.education.gov.uk/munroreview/downloads/8875_DfE_Munro_Report_TAGGED.pdf

Nikku, B.R. (2012). Building Social Work Education and the Profession in a Transition Country: Case of Nepal. Asian Social Work and Policy Review, 6(3), 252–264.

Nikku, B.R. (2010). Social Work Education in Nepal: Major Opportunities and Abundant Challenges. Social Work Education: The International Journal, 29(8), 818-830.

Nikku, B.R. (2009). Social Work Education in South Asia: A Nepalese Perspective. In C. Noble, M. Henrickson and I.Y. Han (eds.) Social Work Education: Voices from the Asia Pacific, (pp. 341-362), Sydney: University of Sydney Press.

Parker, J. (2013). Assessment, Intervention and Review. In M. Davies (ed.) The Blackwell Companion to Social Work (4th ed.) (pp. 311-320). Oxford: Blackwell.

Parker, J. (2015). Single Shared Assessments in social work. In J.D. Wright (ed.) The International Encyclopedia of Social and Behavioral Sciences, (2nd ed.) Elsevier online, Retrieved Feb 2015 from http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/referenceworks/9780080970875#ancpt0935

Parker, J. & Ashencaen Crabtree, S., (2011). Isomorphism and Hegemony: the Bologna process and Social Work Education in the UK. Social Policy and Social Work in Transition, 2(1), 43-56.

Parker, J., Ashencaen Crabtree, S., Azman, A, Carlo, D.P & Cutler, C. (2014). Problematising international social work placements as a site of intercultural learning. European Journal of Social Work, 18(3), 383-396, DOI: 10.1080/13691457.2014.925849.

Parker, J. & Bradley, G. (2014). Social Work Practice, (4th ed.). London: Sage/Learning Matters.

Parker, J. & Doel, M. (2013). Professional Social Work and the Professional Social Work Identity? In J. Parker & M. Doel (eds) Professional Social Work (pp. 1-18), London: Learning Matters/Sage.

Payne, M. (2005). The Origins of Social Work, Basingstoke: Palgrave.

Razack, N. (2009) Decolonizing the Pedagogy and Practice of International Social Work. International Social Work, 52(1): 9–21.

Sheldon, B. & Macdonald, G. (2009). A Textbook of Social Work. London: Routledge.

Smale, G. & Tusan, G. with Biehal, N. and Marsh, P. (1993). Empowerment, Assessment, Care Management and the Skilled Worker. London: NISW/HMSO.

Tan, C. C. (2007). In desperate need: untrained to do social work. New Sunday Times. Retrieved May 2014 from http://www.nst.com.my/nst/articles/19work/Article/.

Turney, D., Platt, D., Selwyn, J., & Farmer, E. (2011). Social Work Assessment of Children in Need: What do we know? Messages from Research. Research Brief. London: Department for Education.

Wenglinsky, H. (2000). How Teaching Matters: Bringing the classroom back into discussions of teacher quality. Princeton, NJ: The Milken Family Foundation and Educational Testing Service.

Williams, J. & P. Nelson (2007). SWIPE “Social Work International Practice Education”: European Collaboration to Develop a Module for Internationalising the Social Work Curriculum. European Bulletin, 10(1), 120–3.

Author´s

Address:

Jonathan Parker

Faculty of Health & Social Sciences

Bournemouth University

Christchurch Road

Bournemouth, UK

BH1 2HU

Tel. +44 (0)1202 962 810

Email: parkerj@bournemouth.ac.uk

Author´s Address

Sara Ashencaen Crabtree

Faculty of Health & Social Sciences

Bournemouth University

Christchurch Road

Bournemouth, UK

BH1 2HU

Tel. +44 (0)1202 962 801

Email: scrabtree@bournemouth.ac.uk

Author´s Address

Azlinda Azman

School of Social Sciences

Universiti Sains Malaysia

11800 Penang

Malaysia

Tel: 04-6533369

Email: dean_soc@usm.my

Author´s Address

School of Social Sciences

Universiti Sains Malaysia

11800 Penang

Malaysia, and

School of Social Work and Human Service

Thomson Rivers University

Kamloops

British Columbia

BC V2C 0C8

Canada

Email: nikku21@yahoo.com

Author´s Address

Uyen Thi Tung Nguyen

VietChin Development Institute

81B, 5th Street, Gyogone

Yangon

Myanmar

Email: uyenceu@gmail.com