The professionalism of professional youth work and the role of values

Judith Metz, Amsterdam University of Applied Sciences

1 Introduction

Due to an unclear professional identity the existence of professional youth work within Northwest European welfare states is subject to debate. There is doubt about the necessity of payment, about the separation from generic social work and about the professionalism. Through the articulation of the specific professionalism of professional youth work including the identification of the core values, I will provide more clarity about the specific professional identity, counter the criticisms and contribute to the continued existence of professional youth work.

The question: What is characteristic for professional youth work’s own professionalism? will be answered through the development of a framework of the specific professionalism of professional youth work. Therefore I use the sociology of professions and relate it to the development of professional youth work in Northwest European welfare states. The sociology of professions gives insight in the phenomenon of labour division and the role that professions play in modern, western societies. A concise discussion of the development of professional youth work provides ingredients for the model of professional youth work’s own professionalism and the identification of the specific youth work values. In the conclusion I will reflect on the strengths and weakness of the framework as well as the implications of the framework for the debate about the future of a separate professional youth work.

2 Precarious practice of professional youth work

Professional youth work within Northwest European welfare states has many appearances and consists of a diverse range of activities, topics and measures that take place in different spaces. On the streets, in malls and sport facilities, in community centres, online or in separate (Metz, 2011a) youth centres professional youth workers offer young people places to be and to meet (Smith, 2013), scope for exploration, activities in the area of urban culture and sport, the opportunity to learn or to organise activities themselves, information and advice, practical help and individual counselling. The diversity within youth work practice is the result of differences in traditions, in geography (country-specificities, urban vs rural, and regional specificities), in needs, dreams and living conditions of young people and in changes in society (Coussee, Verschelden, Walle, Medlinska, & Williamson, 2010; Dunne, Ulicna, Murphy, & Golubeva, 2014; Metz, 2011a). Within these differences there are five marks that identify professional youth work.

· Professional Youth work is positioned in the third domain (Metz, 2011a), also known (Dunne et al., 2014) as the extracurricular area (Council of Europe, 2010) that compared to the home situation (first environment) and school and work (second environment) offers a separate pedagogical regime with a strong sense of freedom, a great appeal of independence and personnel initiative and opportunities for experimentation (Bakker, Noordman, & Rietveld-van Wingerden, 2010; Waal, 2008).

· Starting point for professional youth work is the lifeworld of young people (Metz, 2011a; Metz, 2013b), also described as “were young people are” (Smith, 2013). Physically by working in spaces where young people remain (Dunne et al., 2014). Symbolically by working from the perspectives, experiences, questions and aims from young people (Declaration 1st european youth work convention, 2010; Declaration 2nd european youth work convention, 2015.; Metz, 2011a; Smith, 2013). As a consequence, participation in youth work is voluntarily (Declaration 1st european youth work convention, 2010).

· Professional Youth Work focuses primary on young people living in precarious circumstances (Declaration 2nd european youth work convention, 2015.; Metz, 2011a). Beside the transition from childhood to adulthood (Dunne et al., 2014; Metz, 2011a), these youngsters face a form of marginalisation as a result of deprivation or of a lack of skills, capabilities or possibilities. The age that demarcates youth as category varies between 10 years and 27 years, with the core at 15-24 years.

· Aim of professional youth work is the personal development of young people and the strengthening of their participation on all levels in society, nowadays as youngster and later as adult (Declaration 2nd european youth work convention, 2015.; Dunne et al., 2014; Metz, 2011a; Metz, 2013b);

· Finally, professional youth work is carried out by paid workers who demonstrably master relevant knowledge, skills and attitudes obtained through a combination of formal education, peer-learning and experience in working with young people. In most countries there is no homogenous training system for youth workers (Declaration 1st european youth work convention, 2010; Dunne et al., 2014).

Within Northwest European Welfare states there is doubt about the necessity of (the amount of) payment for professional youth work. Reductions in public spending, the activation of passive citizens who are dependent on the government, and efforts to build social cohesion in response to the advancing trend of individualisation (Newman & Tonkens, 2011) lead to new perspectives on public welfare. Within all public services (including professional youth work) a new balance is being found in what have to be done professionally and which can be better done voluntarily (Metz, Roza, Meijs, Baren van, & Hoogervorst, 2016; Metz, Meijs, Roza, Baren, & Hoogervorst, 2012).

There are also doubts about professional Youth Work as profession separated from social work (Metz, Bos, & Heijden, 2012; Scholte, Sprinkhuizen, & Zuithof, 2012). Just to be clear: in international contexts the notion ‘social work’ has two meanings. It is both used as reference to a collective of different social professions including youth work, youth care and community work and to a specific profession, also the first social profession, and called generic social work. The doubt concerns the separate identity of professional youth work in relation to social work as specific profession (and not professional youth work as part of the collective of different social professions). Arguments against a separate identity of professional youth work are threefold: (further) specialisation within social work hinders the accessibility for clients (Ewijk, 2010); professional youth work and social work share the same mission-statement, target groups, aims and methods (Ewijk, 2009; Raitakari & Virokannas, 2009); professional youth work and social work face the same changes in target groups, societal developments and welfare regimes and will draw closer, even if they respond individually to these challenges (Scholte, Sprinkhuizen, & Zuithof, 2012).

More fundamental there is doubt about the professionalism of professional youth work. Both local and national governments as well as other welfare provisions like schools, youth care and generic social work have difficulties in recognizing the work of youth workers as professional. According to Abdallah (2015) this is due to working in the life world of and tune in on young people. Besides, youth work cannot meet the requirements of evidence-based practice (EBP). None of the Anglophone studies about the effectiveness of youth work matches the standards of EBP (Fouché, Elliott, Mundy-McPherson, Jordan, & Bingham, 2010). An Irish meta-review of effect studies of youth work concludes that no essential effects were identified (Dickson, Vigurs, & Newman, 2013). Internally, youth work has difficulties with the professions elite character as well as professions inclination to protocolise. According to youth workers, this this creates unnecessary distance with the vulnerable youth and badly relates to the emancipatory objectives of youth work (Banks, 2004). Further, within youth work there is still doubt about the need to make a division between professional youth work (delivered by paid workers) and volunteer youth work (delivered by volunteers) (see also 1st & 2nd Declaration European Youth Work Convention 2010, 2015).

3 Professionalism as perspective

The situation appears to be clear initially. All signs points to the end of professional youth work. There are doubts about the need (or amount of) to pay for professional youth work, doubts about the separate identity from generic social work, and finally doubt about the professionalism. Still another explanation for this situation is also possible. It is thinkable that youth work has it’s own professionalism that is not acknowledged as such. The unacknowledged character might also be an explanation for the doubts about the need for payment, for the separation from social work and even for the doubts about the professionalism it self. I come to this perspective because none of the doubts about professional youth work are new. Regular cutbacks show the doubts about the necessity of payment. The continuing debate about the need of separate youth work education shows the doubts about professional youth work as separated from social work. That the fear for protocolisation is justified and volunteers are essential for youth work practice, does not mean that professionalism in itself is wrong.

In her more than an era existence, there have been regular cut backs on professional youth work with the argument that there is no need to fund a separate provision because young people do not need this kind of support or can easily be supported by less educated (read cheaper) workers like youth leaders or volunteers. Mostly these cut backs result in exacerbation of the youth problem, sometimes as worse as an increase in youth crime, drug addiction, teenage pregnancy and radicalisation. After the failure of the repressive approach, professional youth work is asked to build relationships between youth and society, again. This sounds a bit cynic but this cycle appeared for example in the Netherlands, the UK, France, and Austria and did so at the beginning of the twentieth century, during the big recession (’30), in the eighties, and even nowadays (Coussee et al., 2010; Davies, Nutley, & Smith, 2000; Metz, 2013a)

The doubt about professional youth work as profession separated from social work is reflected in the debate about the need of a separate youth work education. Ever since the establishment of the first school of social work in mainland Europe (Amsterdam, 1899) the general social work education is criticized for not being able to educate youth workers that are suited to work with young people in the third domain. When after repeated adjustments the situation did not improve, specific youth work programs were started. Then the debate started about the legitimation of a specific youth work education and the different programs merged into a more generic education after which the criticism started over again. Also this happens in various countries including the UK, the Netherlands and Switzerland (Bradford, 2007/2008; Hope, 2012; Metz, 2013a).

With regard to the doubt about professionalism itself: that is partly justified, specifically when it concerns the fear for the elite character and the protocolisation, and the resistance to EBP. Both the elite character and the protocolisation hinder the open, equal and flexible attitude that is necessary for building relationships with young people. As for EBP, the thinking about interventions as a series of causally linked variables – a pre-condition for experimental effect research – does not do justice to the layered, context-linked and relational character of youth work practice (Coussee, 2009; Duyvendak, Knijn, & Kremer, 2006; Houten, 2008; Metz, 2016; Steyaert, Biggelaar, & Peels, 2010). Youth work methods consists of an extensive repertoire of acts in which the professional choices are made in relation to the development and life world of the youth, the circumstances at the time, long-term objectives and the personality of the worker (Desair, 2008; Kremer & Verplancke, 2004; Spierts, 2005).

About the need to make a distinction between professional youth work and volunteer youth work: it cannot be denied that there is a difference. Because professional youth workers get paid for their job, professional youth work is more expensive and faces other expectations on for example quality and effectiveness. This does not mean that volunteers are not important for professional youth work. Historically and nowadays, separate youth work provisions were initiated by paid workers as well as by volunteers. Most initiatives that were started by volunteers become professional over time. Still, in most professional youth work settings, volunteers play an important role – besides the paid youth worker(s). There is a big variation in the amount of volunteers that take part in professional youth work. This depends on the availability of money for youth work provided by governments or charity. Also identity-driven youth work organisations and youth work provisions in rural areas mostly count relatively more volunteers than youth work in urban areas.[1]

Personally, I believe that the articulation and strengthening of the specific professionalism of professional youth work is the only route for survival of contemporary practice in which specific professional youth work appears one of the few actors that are able to bridge the extending gap between young people and society (of which radicalisation is an expression). A clear identity contributes to the acknowledgement of youth work as separate profession by governments, other social work provisions and schools. Also it functions as starting point for the further development of professional youth works specific body of knowledge and skills that fits to practice of working with young people in the third domain and forms an answer to evidence based practice. Further, it makes it possible for professional youth work to take account for it’s influence on both the life of young people and society as a whole. All together this strengthens the position of youth work in society which is needed to be able to protect young people from the increasing violation of their basic human rights by both globalisation and changing regimes of Northwest European welfare states.

4 Professions and their professionalism

The sociological theory of professionalism of professions moves between three poles: objective rationality, moral responsibility and democratic practice. In theory as well as in practice: objective rationality is dominant. The undercurrent that draws attention to both the moral and democratic responsibilities of professions is at least as important for the quality and public assignment of professional youth work. Objective rationality involves realising the intended goals as efficiently and effectively as possible. Efficiency entails costing as little as possible and effectiveness entails being based on scientific knowledge about causality (Houten, 2008). Moral responsibility refers to the profession specific assignment regarding both the common good of society and the personal interest of clients, this includes continuous balancing of what is good (and what is bad), and why that is good (and respectively bad) (Kunneman, 2012). Democratic practice refers to the duty of professions “to enable (and not disable) citizen participation within their spheres of professional authority” (Dzur, 2004, p6). This to reduce the harm that professions do to democracy, on society level by performing duties that are the responsibility of lay people and on the individual level by disempowering citizens. I will now elaborate on the three poles and relate this to what is known about the advancing professionalisation of professional youth work.

4.1 Objective rationality

The domination of objective rationality is the consequence of the labour division which emerges from scientific insights in modern, western societies (Houten, 2008). A study carried out in the nineteen thirties into the characteristics of classic professions such as doctor, judge and lawyer, still serves now as a model for professionalism: the enclosure of the professional group by means of the registration of professional practitioners and the taking of a professional oath; the monitoring of the quality of professional practice including the right to suspension; the availability of specialised knowledge and techniques on an academic level and training (Carr-Saunders & Wilson, 1933).

Just like the other social professions for that matter, youth work cannot meet the conditions for a classic profession (Coussee et al., 2010; Devlin, 2012; Duyvendak et al., 2006; Fusco, 2012; Houten, 2008; Lorenz, 2009; Metz, 2013a). For example, in the Netherlands youth work has only had a professional association for the last five years (called BV Jong, Youth Ltd), a national code of behaviour is in development and there is no registration of youth workers. As education concerns, there exists a route for specialisation within vocational education, a minor youth work and a post-bachelor program in youth work. (Practice) research on youth work is in development (Metz, 2011a).

The economic crisis and the mass unemployment in the eighties resulted in the introduction of New Public Management (NPM) as the government’s governance principle, the emphasis comes to lie on monitoring, cost control and outcomes (Noordegraaf, 2007). All social and welfare professions, including youth work, have to deal with accountability and protocols. The popularity of EBP within the government forces all social work professions to prove that their work is effective. European legislation has made it possible that welfare work can be contracted out with the consequence that the government determines the contents of all social professions (Metz, 2011b).

Youth work wrestles with this unilateral attention to objective rationality. This is because youth work is reduced to supervising the individual learning processes of young people as transparently and effectively as possible and both the social assignment as well as the pedagogical and social context disappear from sight (Coussee et al., 2010; Coussee, 2009). On a practical level, youth work still has a small body of knowledge with an even more limited theoretical and empirical fundament (Metz, 2016; Metz, 2012)). Most of the knowledge is experience-based: both from being a professional youth worker and a member of the target-group (Spierts, 2005). The realisation of a separate body of knowledge has been difficult for three reasons. Firstly, for youth work, innovation is a permanent process. Both society and young people are in continuous development. Social developments and trends amongst young people – negotiated through governmental policy – result in changing assignments for youth work. As a consequence youth work has to develop new methods constantly and has little time to substantiate existing methods (Metz, 2011a). Secondly, because youth work is a relatively small area tension thus exists between it having sufficient scope to offer the necessary quality while at the same time having to be specialist enough to be in keeping with the specific professional practice (Metz, 2013a). Thirdly, as mentioned before, the limitation of Evidence Based Practice to a causal series of acts does not do justice to the complexity and dynamics of youth work practice.

Youth work cannot meet the requirements of accountability and evidence-based practice. In most Northwest European welfare states this sort of work is subject to extensive turmoil. It is forced to reform itself or have to deal with severe cutbacks (Garret, 2002; Metz, 2011b; Smith, 2007). The professionalisation of youth work comes high on the political, social and its own agenda. Youth work starts to experiment. Great Britain comes up with a large-scale campaign entitled: In Defence of Youth Work (IDOYW, 2011). Ireland is occupied with the development of a national quality system for volunteer youth work. In the Netherlands youth work organisations and youth work education set to work on bottom-up method development (Metz, 2012). In addition specific monitoring instruments for measuring the results of youth work are developed: Jongerenwijzer (Youth Indicator), Jongeren in Beeld (Young People in the Picture) and Jongeren in Kaart (Mapping Youth).

4.2 Moral responsibility

What is missing within the objective rationality approach to professionalism is attention for the moral responsibility of professions. At the end of the nineteenth century Durkheim was one of the first sociologists to demand that attention is to be paid to this (Duyvendak et al., 2006; Ewijk & Kunneman). Durkheim argues that in comparison with citizens, civil servants and technicians, professionals have a different moral position: they serve the common good and should thus function as a moral example. They also play a role in strengthening social cohesion by forming circles together with colleagues in which they share and propagate their expertise and ethics (Durkheim, 1957). In this, Durkheim refers to the guild system of the Middle Ages. At that time Durkheim’s work meets little response (Dewey, 1910; Polanyi, 1966; Sennet, 2008).

This changes in 2001 with the appearance of Freidson’s Professionalism: the third logic and Flyvbjerg’s appeal for Aristotle’s’ phronesis, both written as a reaction to the unilateral domination of an objective rational professionalism. Freidson comes to the conclusion that the intellectual capital which guarantees the quality of the work of the professional, requires discretionary scope for professional action which is threatened by efficiency, standardisation and protocolisation of the logic of the market and bureaucracy (Freidson, 2001). Flyvbjerg presumes that the scientific model of the natural sciences (objective rational) is not suited for understanding human interactions. Universal truths (episteme) and technical knowledge (techne) provide inadequate mainstays for dealing with social problems in specific circumstances. For this reason phronesis is necessary, the consciousness of specific values and interests which constitute the foundation of human relationships and the evaluation capacity, on the basis of which good decisions can be made in daily practice (Flyvbjerg, 2001).

In the supervision of young people in such a way that they become fully-fledged adults (Metz, 2011), youth work has pre-eminently an educational and thus moral assignment. Both in the United States as well as Great Britain attention turns to the independent moral responsibility of the profession. Phronesis as brought to the attention by Flyvbjerg (2001) is the source of inspiration (Ord, 2012; Walker & Walker, 2012). In contrast, Sercombe (2010) elaborates upon the work of Koehn (1994), who contends that the heart of the profession is formed by the commitment of the professional to his or her assignment. The core of this commitment is a moral obligation (Koehn, 1994). The classic characteristics of a profession, such as a code of behaviour, professional association, training and expertise, are pre-conditions for being able to interpret this moral responsibility in a good manner (Sercombe, 2010).

Subsequently it is the question of how the moral responsibility of youth work relates to young people’s own responsibility and world image and the communities in which they grow up. Flyvberg proposes that phronesis forms the core, even if techne and episteme are applied in specific situations (Flyvbjerg, 2001). In 2012 Banks further elaborates on this idea for social work in general. The relationship between the social professional and the client form the basis, without a relationship there is no social work. At the same time Banks observes that a personal relationship is risky because personal sympathies or preferences take the upper hand. So it is the professional expertise (craftsmanship and knowledge) that makes the difference between professional social work and, for example, charity or voluntary work. To bring these two in balance strong professional ethics are needed, combined with the capacity for normative reasoning: ‘This requires a capacity and disposition for good judgement based in professional wisdom and a process of practical reasoning or ‘ethics work’ to find the right balance between closeness and distance, passion and rationality, empathic relationships and measurable social outcomes. It also requires a space for the exercise of professional wisdom’ (Banks, 2012).

4.3 Democratic practice

Democratic practice as perspective on professionalism dates from the sixties and seventies when societal relationships were in a state of change. Throughout the western world authoritarian practices, including professions, are questioned by mass social movements (Clark & Newman, 1997). Disabling professions is one of the expressions of this viewpoint: with their status and protected position, professions exercise power over their clients and in doing so make clients dependent on them and deprive them of their self-direction (disempowerment) (Illich, 1977). Off all professions this criticism hit social work hardest because specifically social work claims to empower and liberate citizens (Tonkens & Duyvendak, 2003).

Youth work, however, embraces the criticism, changes the practice and becomes an important facilitator of the mass social movements. ‘Being young together’ becomes the basis of pedagogical ideology (Poel, 1997; Smith, 2013). Mutual relationships between young people and adults are central to this process. It is not longer appropiate to approach young people with either a spescific intention or to intervene in the development of a young person (Hazekamp & Zande, 1992). The youth worker acquires the role of facilitator and the task of creating a supportive environment (Metz, 2013b; Smith, 2013).

The democratisation, and more specific the criticism on professions, eases the implementation of NPM which also containes a democratic promise. To combat disempowerment, NPM promise to empower citizens as clients who would have the power to choose. As alternative for paternalism, NPM promises to refrain from judgement and simply deliver what is asked for. Through performance measurement the quality of services will become transparant, after which citizens get the possiblity of choice (Tonkens, Hoijtink, & Gulikers, 2013). In practice (local) governments enlarged their control on social work professions in the name of citizens. Besides client participation sets in (Haaster, 2001).

In the development of democratic practice, professional youth work has it’s own process. Allready in the seventies it started working with egalitarian relationships between youth workers and young people. In the eigthies and nineties, youth work does not recognize the innovational character of demand-oriented social services. Instead youth work faces the negative consequences of youth-led youth work and poor supervision: youth centres become spaces of violence, drugs, and crime. Youth work start to re-invent the relationship by finding a new balance between the mutual and the pedagogical (Metz, 2011a). Because youth work considers it’s practice as supportive of youth participation on the personal level, it is neglecting the developments on formal youth participation. After the ratification of UN Convention on the Rights of the Child in 1989, youth participation became high on the European and national political agenda.

With the publication of Democratic professionalism (2004), Dzur points out that it is counterproductive to oppose professionals and citizens with (local) governments as mediator. Professionals cannot function without their professional authority, this because their specialism is needed to be able to deliver their services. Citizens also have authority, but that is based on experience and on their civil rights. By putting the (local) government in between, citizens are further disempowered because there is even less space for their personal perspectives. Instead Dzur pleads for sharing autority in public life by way of dialogue on the individual, group and collective level. For professionals this would lead to a new role: facilitating the involvement of the public by working collaboratively with lay people, enable them to deliberate and make decisions in issues that affects them (Dzur, 2004).

5 Professionalism of youth work

What do we learn from this about the professionalism of youth work? On the basis of sociological theory of professions and the development of professional youth work practice I have arrived at the following model of the professionalism of youth work:

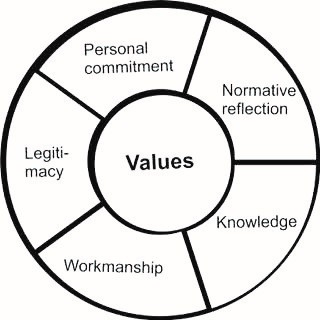

Figure 1: Professionalism of professional youth work

Figure 1 depicts the professionalism of youth work. The key values in the middle provide direction for practicing the profession. The preconditions are grouped around to ensure qualitatively good professional practice.

The central values form the core of professional practice and are both applicable to the youth workers individually as well as to youth work as a profession. This explicit normative position is important because professional youth work is of great influence on the lives of young people and society as a whole. The values function both as direction and anchor point. This is needed because professional youth work is carried out by individuals in changing situations and contexts were continually considerations have to be made about what has to be done. The key values of youth work provide the direction for these considerations. At the same time they provide an anchor point for the dialogue with societal forces and personal convictions.

The five preconditions ensure that professional practice has good quality. The first precondition is the personal commitment to young people, because young people (and their life worlds) constitute the starting point of professional youth work (see also the five marks that characterize professional youth work). The first loyalty of the youth worker concerns the young. Subsequently normative reflection is necessary. Normative reflection refers to the moral consciousness and capacity of judgement that are necessary for being able to make decisions about practicing the profession in interaction with young people and their environment and in line with the key values. Afterwards knowledge and workmanship are needed for a qualitatively good informed and executed practice. Knowledge is the most important merit of objective rationality: the possibility of having better knowledge about what works for who. Youth workers are expected to be aware of the latest insights and able to apply them in their work. Workmanship refers to the mastery of the work in such a way that professionals in action are able to respond to the unexpected and sometimes unmanageable material with which they are confronted (Gradener, 2013; Sennet, 2008). Finally, legitimacy refers to providing accountability about the application of professional youth work. This takes place on three levels: 1) in contact with young people, as counter weight to the professionals’ position of power in relation to clients (Dzur, 2004; Dzur, 2008; Illich, 1977; Tonkens et al., 2013)and as part of the pedagogical assignment to make young people owner of the process of becoming an adult (Metz & Sonneveld, 2013); 2) in discussions with colleagues (as a form of monitoring the quality and jointly learning about how diverse methods work) and 3) with regard to funders (transparency in spending public financial resources).

6 Youth work values

What are the key values of professional youth work which form the heart of its professionalism and provide direction in daily professional practice? The international dialogue about the key values of professional youth work is slowly starting (Banks, 2004; Banks, 2012; Ewijk, 2010; Walker & Walker, 2012). In this article, I underline the existence of an independent moral responsibility of professional youth work that is not negotiable. At the same time I provide a contribution to the beginning dialogue with the identification of three key values. From the perspective of the legitimacy of professional youth work I come to three key values: development-oriented, social justice and full participation.

6.1 Development-oriented

Development-oriented is a key value in youth work because youth work is occupied with young people who are developing into adulthood (Metz, 2011a). I define development-oriented as paying attention to the – broad, positive and long-term – development of young people. In my view this concerns the personal, social and societal development into becoming a fully-fledged human being, which consists of a combination of identity formation with emotional and moral development, the learning of life skills and social and civic participation (Bradford, 2012; Dieleman, 2012; Veugelers, 2011). This can contribute to citizenship formation, prevention or cure, but that is not the primary focus. For citizenship formation, prevention and cure, the development has a specific objective established in advance. Development-oriented requires that young people themselves direct the process of becoming an adult. In the personal development to independence it currently concerns the acquisition of agency (Beck, 1992; Dieleman, 2012; Lash, 1999): from today’s adults it is expected that they are able to make choices independently, seize opportunities and take responsibility for themselves in relation to others and society as a whole.

Development-orientation has always been an important value in youth work. Along with the awareness that being young is a separate life phase comes the insight that young people should be given the opportunity to learn what they need to become a fully-fledged human being as adult (Metz, 2013b). The necessity for working with a development-orientation in professional youth work is still growing. Due to individualisation and economisation of the welfare state, people become more and more on their own. To be able to face future expectations young people need the maximum opportunities to develop themselves. Youth work is the only welfare provision that supports young people on their own terms.

What does this mean in practice for professional youth work? Youth work always works with a development-orientation also when specific problems are the reason for the deployment of professional youth work. This involves that youth workers ensure that young people direct their own development processes, address every question, issue or dream as an opportunity for exploration, experiment and learning, and finally work on the enlargement of the possibilities for young people to explore, experiment and learn.

6.2 Social justice

Social justice is the second key value in youth work because youth work is directed at those young people, individuals and groups, who are in need for support in becoming adults as part of society. Social justice as key value consists of three matters: (1) striving for equality in outcomes as opposed to equality in opportunities; (2) striving for an honest division of social facilities, sources of help and power in a manner which is in accordance with what is needed; (3) the recognition of diversity and difference (in terms of gender, ethnicity, class, limitations and sexuality) (Banks, 2011). The guiding principle of social justice consists of a combination of self-determination, social responsibility and human rights (Ewijk, 2009; Ewijk, 2010).

Social justice as value stems from the originating of professional youth work when at the end of the nineteenth century rising industrialisation changed society and young people became estranged from their communities, hang around on the streets and undergo radicalisation (Coussee, 2009; Metz, 2011a). Ever since, the need of young people in support of becoming part of society has been the reason for initiating (professional) youth work provisions. The underlying cause can be a matter of generation (youth as category), of social issues (youth facing deprivation) or of diversity (the recognition of difference both within youth as well as within society). In the years to come, a growing appeal on social justice is to be expected. The reformation of Northwest European welfare states results in a clash between generations in which until now young people lose ground. Also in matters of climate change or environmental pollution it are the next generations who face the consequences. The widening gap within welfare states calls upon the social dimension of social justice. An increasing amount of young people grows up in precarious circumstances. Besides the need to overcome a form of deprivation, these youngsters also face social exclusion and a lack of resources and possibilities. When it comes to the recognition of difference, Northwest Europe faces a completely new situation in which big cities have become official minority-cities where no ethnic group can claim to be the dominant group while the smaller cities and rural regions stay mainly unchanged except for the arrival of refugees.

For professional youth work practice this has three consequences. The first is the choice of the target group. Although professional youth work is a facility for all young people, young people in need will require the primary and probably most attention. The second consequence is that professional youth work itself should be an inclusive practice where young people of different backgrounds meet and together develop democratic ways in how to deal with diversity. The third consequence is that youth work supports young people in (1) understanding how social structures produce oppression, inequality, social exclusion and the isms like racism, sexism, homophobia and Islamophobia; (2) find out how this all affects their life in person and as group, and (3) search for ways to overcome this both on the personal and on the structural level.

6.3 Full participation

Because professional youth work is directed at supervising young people in becoming adults within society, full participation is the third value. Full participation refers to the perspective on the way in which young people now and later as adult are part of democratic society. Full participation means to be able to take part in and give shape to society. This expects from young people to participate in society and from society to open up for the being, aims, dreams and needs from young people (participation as democratic process) (Coussee, 2009; Lorenz, 2009; Winter, 2000).

Like development-oriented and social justice, full participation has always been an important value in youth work. Full participation stems from the legitimacy of professional youth work and is well-understood self-interest in the continued existence of democratic society. Because young people are growing up in current times, they are better equipped than older generations for dealing with contemporary questions and manners and are therefore the bearers of social innovation. According to Dewey (1923) and underlined by contemporary political theorists and pedagogues like Dzur (2004, 2008) and De Winter (2000; 2012) democracy cannot be learned but has to be found out by each generation themselves. Finally, in the face of the increase of terror and repression, it is important to remember that social stability is an important achievement of Northwest European welfare states that until now makes it possible that people living in Northwest European welfare states are safe and can live in peace and freedom.

In practice, full participation means that youth work has an assignment to both young people and society. Support young people in taking part and have influence in society bears both an aspect of self-development as well as one of adaption. Self-development concerns helping young people to discover their capabilities, develop them and find out how they want and are able to use them in within society. Adaption concerns giving young people the opportunity to become aware of social codes and norms of democratic practice and mastering the skills for being able to meet them. Support society in opening up for young people means support in becoming aware of the human rights, needs, dreams and aims of young people, support in the creation of separate spaces for the being of young people, support in opening up contemporary practices like neighbourhood councils, labour market or volunteering for the participation of young people and finally when needed support in the provision of specific services for young people like school mentoring projects, housing opportunities or youth dept counselling.

7 Implications and conclusion

Aim of the article is to contribute to more clarity about professional youth work specific professionalism in the ambition to counter the doubts about the need of a separate professional youth work as well as about the professionalism of professional youth work practice. This through the development of a framework of the professionalism of professional youth work. To what extend did the article manage to realise the ambition?

The short overview of the theory of professions makes visible that the theory of professions is still evolving around three poles that function as anchorpoint. For professional youth work this means that there is space for the development of an own professional identity and that besides the objective rationality of which evidence based practice is an expression also moral responsibility and democratic practice are part of professionalism. The framework that is the result of the application of the sociological theory of professions to the development of professional youth work practice shows that it is possible to identify the specific professionalism of professional youth work in such a way that it fits with the layered, context-linked and relational character of youth work practice.

Does the framework of professionalism of professional youth work provides the clarity about the professional identity that is aimed for? The framework itself offers mainly clarity about the structure and specific aspects of professionalism of youth work and is only the first attempt to identify the core values. Therefor the framework is quite generic and needs further elaboration and debate. The strength of this framework is that with the structure, a language is available to explain the specific aspects of youth work professionalism as well as good clues for the further development of youth work specific professionalism.

Are the doubts about the professionalism of professional youth work practice countered? The framework makes visible that professional youth work is a comprehensive profession that sets high demands on individual youth workers and hardly can be met by volunteers solely. Although the framework is still generic, the core values in combination with the specific target group, the specific aim, the position of youth in society and the working in the life world show that youth work is a profession separate from social work.

And the doubts about professionalism of youth work practice itself? The framework makes visible that professional youth work is indeed a professional practice. The theory of professions leaves no ground for resistance to the professionalisation of professional youth work in general because it is part of the specific responsability of both the profession and the individual professional to overcome the negative effects. Instead professional youth work should invest in the development of the specific professional practice in line with this framework. This includes agreement on the required competences, appropriate learning facilities, a body of knowledge that is based in youth work practice and not only in theory or professional intuition, dialogue on the core values of professional youth work and finally the development of strong, independent professional association(s).

References

Bakker, N., Noordman, J., & Rietveld-van Wingerden, M. (2010). Vijf eeuwen opvoeden in nederland. idee en praktijk 1500-2000. Assen: Van Gorcum.

Banks, S. (2004). Ethics, accountability and the social professions. Basingstoke: Palgrave, Macmillan.

Banks, S. (2011). Ethics in an age of austerity: Social work and the evolving new public management. Journal of Social Intervention, 20(2), 5-23.

Banks, S. (2012). Negotiating personal engagement and professional accountability: Professional wisdom and ethics work. European Journal of Social Work, 1-18.

Beck, U. (1992). Risk society. towards a new modernity. London: Sage.

Bradford, S. (2007/2008). Practices, policies and professionals. the emerging discourses of expertise in english youth work 1939-1951. Youth & Policy, (97/98), 13-28.

Bradford, S. (2012). 2. growing up in the present. from 1945 to the 2000s. In S. Bradford (Ed.), Sociology, youth & youth work practice (pp. 28-54). Hampshire/New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Carr-Saunders, A., & Wilson, P. M. (1933). The professions. London: Oxford University Press.

Clark, J., & Newman, J. (1997). The managerial state: Power, politics and ideology in the remaking of social welfare. London: Sage.

Council of Europe. (2010). Resolution of the council of europe and of the representatives of the governments of the memberstates. meeting within the council on youth work, 3046th EDUCATION, YOUTH, CULTURE and SPORT council meeting, brussels, 18-19 november 2010.

Coussée, F., Verschelden, G., Walle, T. v. d., Medlinska, M., & Williamson, H. (2010). The history of european youth work and its relevance for youth policy today - conclusions. In F. Coussee, G. Verschelden, T. v. d. Walle, M. Medlinska & H. Williamson (Eds.), The history of youth work in Europe. Relevance for today’s youth policy (pp. 125-136). Strasbourg: Council of Europe publishing.

Coussée, F. (2009). The relevance of youth work's history. In G. Verschelden, F. Coussee, T. v. d. Walle & H. Williamson (Eds.), The history of youth work in Europe, volume 2, (pp. 7-12). Strasbourg: Council of Europe publishing.

Davies, H. T. O., Nutley, S. M., & Smith, P. C. (2000). What works? evidence-based policy and practice in public services. Bristol: Policy Press.

Declaration 1st European Youth Work Convention, ghent, belgium, 7-10 juli 2010.

Declaration 2nd European Youth Work Convention, making a world of difference, brussels, 27-30 april 2015.

Desair, K. (2008). Hoe wetenschap en werkveld samen zoeken naar effectiviteit. Alert, (2), 24-33.

Devlin, M. (2012). Youth work, professionalism and professionalisation in Europe. In F. Coussee, H. Williamson & G. Verschelden (Eds.), History of Youth Work, volume 3, (pp. 177-190). Strasbourg: Council of Europe publishing.

Dewey, J. F. (1923). Democracy and education. an introduction in the philosophy of education. New York: MacMillan.

Dewey, J. (1910). How we think. Boston: D.C. Heath.

Dickson, K., Vigurs, C. A., & Newman, M. (2013). Youth work. A systematic map of the research literature. Dublin: CES.

Dieleman, A. (2012). Een nieuwe blik op jongeren. In J. Hermes, P. Naber & A. Dieleman (Eds.), Leefwerelden van jongeren. Thuis, school, media en populaire cultuur (pp. 17-40). Bussum: Coutinho.

Dunne, A., Ulicna, D., Murphy, I., & Golubeva, M. (2014). 2. what is youth work? In A. Dunne, D. Ulicna, I. Murphy & M. Golubeva (Eds.), Working with young people: The value of youth work in the european union (pp. 53-87). Brussels: IFC GHK.

Duyvendak, J. W., Knijn, T., & Kremer, M. (2006). Policy, people and the new professional. an introduction. In J. W. Duyvendak, T. Knijn & M. Kremer (Eds.), Policy, people and the new professional. de-professionalisation and re-professionalisation in care and welfare (pp. 7-17). Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Dzur, A. W. (2004). Democratic professionalism: Sharing authority in the public life. The Good Society, 13(1), 6-14.

Dzur, A. W. (2008). Democratic professionalism, citizen participation and the reconstruction of professional ethics. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press.

Ewijk, H. v. (2009). European social policy and social work. citizenship based social work. London: Routledge.

Ewijk, H. v. (2010). Maatschappelijk werk in een sociaal gevoelige tijd. Amsterdam: SWP.

Ewijk, H. v., & Kunneman, H. K. Praktijken van normatieve professionalisering. Amsterdam: Humanistic University Press.

Flyvbjerg, B. (2001). Making social science matter: Why social inquiry fails and how it can succeed again. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Fouché, C., Elliott, K. J., Mundy-McPherson, S., Jordan, V., & Bingham, T. (2010). The impact of youth work for young people: A systematic review. Wellington: New Zealand Ministry of Youth Development and the Health Research Council of New Zealand Partnership Programme.

Freidson, E. (2001). Professionalism. the third logic. On the practice of knowledge. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Fusco, D. (2012). On becoming an academic profession. In D. Fusco (Ed.), Advancing youth work: Current trends, critical questions, (pp. 111-126). New York: Routledge.

Garret, P. M. (2002). Encounters in the new welfare domains of the third way: Social work, the connexions agency and personal advisers. Critical Social Policy, 22, 596-618.

Gradener, J. (2013). Samenwerking is een ambacht. richard sennet en de noodzaak van community workers. Tijdschrift Voor Sociale Vraagstukken, 1, 12-15.

Haaster, H. P. M. (2001). Cliëntenparticipatie. Bussum: Coutinho.

Hazekamp, J., & Zande, I. v. d. (1992). Het jongerenwerk in hoofdlijnen. Amsterdam: Uitgeverij Balans.

Hope, M. (2012). Youth workers and state education. should youth work set up a free school? Youth & Policy, (109), 60-70.

Houten, D. J. (2008). Professionalisering: Een verkenning. In G. Jacobs, R. Meij, H. Tenwolde & Y. Zomer (Eds.), (pp. 16-35). Amsterdam: SWP.

In Defense Of Youth Work. (2011). This is youth work. stories from practice UK: IDOYW.

Illich, I. (1977). Disabling professions. notes for a lecture. Contemporary Crises, 1, 4, pp 359–370.

Koehn, D. (1994). The ground of professional ethics. London: Routledge.

Kremer, M., & Verplancke, L. (2004). Opbouwwerkers als mondige professionals. de praktijk van accountability, marktwerking en vraaggericht werken op lokaal niveau. Utrecht: LCO en NIZW.

Kunneman, H. K. (2012). Introduction: Craftsmanship and normative professionalisation. In H. K. Kunneman (Ed.), Good work. The ethics of craftsmanship (pp. 3-12). Amsterdam: Humanistic University Press.

Lash, S. (1999). Another modernity; a different rationality. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers.

Lorenz, W. (2009). The function of history in the debate on social work. In G. Verschelden, F. Coussée, T. v. d. Walle & H. Williamson (Eds.), The history of youth work in Europe. Relevance for todays youth policy, (pp. 19-28). Strasbourg: Council of Europe publishing.

Metz, J. W. (2016). De ontwikkeling van een met onderzoek onderbouwde methodiek voor het meidenwerk. Journal of Social Intervention, 25(1), 47-70.

Metz, J. W., Roza, L., Meijs, L. C. P. M., Baren van, E. A., & Hoogervorst, N. (2016). Differences between paid and unpaid social services for beneficiaries. European Journal of Social Work, doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13691457.2016.1188772

Metz, J. W. (2011a). Kleine stappen, grote overwinningen. jongerenwerk als historisch beroep met perspectief. Amsterdam: SWP.

Metz, J. W. (2011b). Welzijn in de 21ste eeuw. van sociale vernieuwing naar welzijn nieuwe stijl. Amsterdam: SWP.

Metz, J. W. (2012). Jongerenwerk als werkplaats voor professionalisering. Journal of Social Intervention, (21), 18-36.

Metz, J. W. (2013a). History illuminates the challenges for youth work professionalisation. In R. Gilchrist, T. Jeffs, J. Spence, N. Stanton, A. Cowell, J. Walker & T. Wylie (Eds.), Reappraisals. Essays in the history of youth and community work, Dorset: Russell House Publishing.

Metz, J. W. (2013b). De waarde(n) van het jongerenwerk. Amsterdam: HvA publicaties.

Metz, J. W., Meijs, L., Roza, L., Baren, E., & Hoogervorst, N. (2012). Grenzen aan de civil society. In H. Jumulet, & J. Wenink (Eds.), Zorg voor ons zelf. Eigen kracht van jeugdigen, opvoeders en omgeving , grenzen en mogelijkheden voor beleid en praktijk. Amsterdam: SWP.

Metz, J. W., & Sonneveld, J. J. J. (2013). Het mooie is dat je er niet alleen voor staat. individuele begeleiding van jongeren. Amsterdam: SWP.

Newman, J., & Tonkens, E. (Eds.). (2011). Participation, responsibility and choice. summoning the active citizen in western European welfare states. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Noordegraaf, M. (2007). From "pure" to "hybrid" professionalism: Present-day professionalism in ambigious public domains. Administration and Society, 39(6), 761-785.

Ord, J. (2012). Aristotle, phronesis & youth work; measuring the process: A contradiction in terms … ? Oral presentation. Positivity in Youth Work, an International Conference on Youth Work and Youth Studies. Glasgow: University of Strathclyde.

Poel, Y. te (1997). De volwassenheid voorbij. professionalisering van het jeugdwerk en de crisis in de pedagogische verhouding 1945 - 1975. Leiden: DSWO Press.

Polanyi, M. (1966). The tacit dimension. New York: Double day and company.

Raitakari, S., & Virokannas, E. (Eds.). (2009). The shared fields of youth work and social work. discussions of professions, practices and convergances. Finnish Youth Network.

Scholte, M., Sprinkhuizen, A. M. M., & Zuithof, M. (2012). De generalist. de sociale professional aan de basis portretten en conceptuele verkenningen. Houten: Bohn, Stafleu, Van Loghum.

Sennet, R. (2008). The craftsmen. London: Penguin Books.

Sercombe, H. (2010). Youth work ethics. London: Sage.

Smith, M. K. (2013) ‘What is youth work? Exploring the history, theory and practice of youth work’, the encyclopedia of informal education, www.infed.org/mobi/what-is-youth-work-exploring-the-history-theory-and-practice-of-work-with-young-people/. Retrieved:12 August 2016.

Smith, M. K. (2000, 2007) 'The Connexions Service in England', the encyclopaedia of informal education. [www.infed.org/personaladvisers/connexions.htm. Last update: July 08, 2014]

Spierts, M. (2005). Een 'derde' weg voor sociaal-culturele professies. Journal of Social Intervention, (1), 13-21.

Steyaert, J., Biggelaar, T. v. d., & Peels, J. (2010). De bijziendheid van evidence based practice. beroepsinnovatie in de sociale sector. Amsterdam: SWP.

Tonkens, E., & Duyvendak, J. W. (2003). Paternalism, caught between rejection and acceptance. Community Development Studies, 38(1), 6-15.

Tonkens, E., Hoijtink, M., & Gulikers, H. (2013). Democratizing social work: From new public management to democratic professionalism. In M. Noordegraaf, & B. Steijn (Eds.), Professionals under pressure. The recognizion of professional work in changing public services. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Veugelers, W. (2011). A humanist perspective on moral development and citizenship education. empowering autonomy, humanity and democracy. Education and humanism. Linking autonomy and humanity (pp. 9-34). Rotterdam: Sense publishers.

Waal, V. d. (2008). Uitdagend leren. Culturele en maatschappelijke activiteiten als leeromgeving. Bussum: Coutinho.

Walker, Y., & Walker, K. (2012). Establishing expertise in an emerging field. In D. Fusco (Ed.), Advancing youth work: Current trends, critical questions, (pp. 39-51). New York: Routledge.

Winter, d., M. (2000). Beter maatschappelijk opvoeden. hoofdlijnen van een eigentijdse participatiepedagogiek.. Assen: Van Gorcum.

Winter, M. d. (2012). The educative civil society als remedy: Breaking the stressfull double bind of childrearing and socialisation. Socialisation and civil society. how parents, teachers and others could foster a democratic way of life (pp. 35-54). Rotterdam, Boston & Taipei: SENSE publishers.

Author´s

Address:

Dr. Judith Metz

Professor Urban Youth Work

School of Social Work and Law

Amsterdam University of Applied Sciences

j.w.metz@hva.nl

http://www.hva.nl/profiel/m/e/j.w.metz/j.w.metz.html