European welfare states constructing “Unaccompanied Minors” – A comparative analysis of existing research on 13 European countries

Philipp Sandermann, Leuphana University of Lüneburg

Onno Husen, Leuphana University of Lüneburg

Maren Zeller, Trier University

Introduction

There has been a relentlessly rising number of young people who have left their countries “to escape conditions of serious deprivation or exploitation” (Ferrara et al. 2016), and who arrived without any legal guardian in foreign – mostly so-called “Western” – countries over the course of the last ten years. During this period of time, in the EU the number of asylum applicants considered to be UAM rose from 11 695 in 2008 to 63 290 in 2016 (Parusel 2017), while the total number of young people usually referred to as UAM (including those who do not apply for asylum) rose even higher.

The year of 2015 stands for a historical peak during this development.[1] Due to this, the phenomenon of UAM has been constantly more recognized. Meanwhile, research on UAM spreads across various academic disciplines and countries, and over the course of this development, there has been an obvious increase of academic publications on the topic. The degree to which such publications reflect their respective research focus, and the social construction of UAM as a category, varies considerably though. Moreover, so far, comparative perspectives on UAM are rare. The article at hand addresses both of these desiderata to provide a comparative perspective on UAM in Europe while reflecting on the broader contexts that make it possible to even speak of young people as UAM. To do this, we will start with a brief sketch of existing comparative research on UAM (section 1), then expose our theoretical framework and research question (section 2) before outlining our method and sample (section 3). After this, we will present our main findings and theoretical interpretations (section 4) of differences and commonalities in how European welfare states construct young people as “Unaccompanied Minors”. The article ends with a brief summary.

1 Comparative perspectives on young people called Unaccompanied Minors – state of research

Currently, there exist only few comparative analyses that address the topic of UAM. Those decidedly comparative investigations on the topic that are available mostly focus on two or three countries, or even different regions of a single country, and follow rather specific research questions (e.g. Kaukko & Wernesjö 2016; Lidén & Nyhlén 2016).

Moreover, there are statistical overviews framed by political statements and advice that refer to the presented data to „find ways to help the unaccompanied minors“ (Celikaksoy & Wadensjö 2016). For instance, Eurostat,[2] and international organizations like Unicef, UNCHR, Save the Children, and Amnesty International provide such data, reports and statements. Most of these papers are of high value where it comes to identifying good practices for policy makers. However, they do hardly reflect on a theoretical perspective from which they actually describe the data that is being presented (Parusel 2011), and are therefore not to be considered as precisely comparative analyses.

The comparative work of the European Migration Network (EMN) of the European Commission somewhat makes a difference in this respect, as it has been committed to offer policy makers a well-founded perspective on UAM in Europe monitoring policies and practices by providing statistics and identifying important knowledge gaps, and does so by virtue of a decidedly comparative approach. E.g. where it comes to non-asylum seeking refugee children, vanished, previously registered UAM, and the question of what happens to UAM coming of age, the EMN reports offer a whole bunch of comparative research questions and valuable comparative perspectives (European Migration Network 2010; 2015a; 2015b). But even the EMN reports represent only a first step towards a decidedly comparative perspective on UAM, as they mainly represent the most elaborated version of an international debate on UAM that until today has rather added national policy debates on UAM to one another than deconstructed them to provide for an international comparison on UAM in a narrower sense.

In sum, the academic debate on UAM has in fact started to draw from research findings and theoretical reflections on the national level to generate arguments on an international level, but has hardly developed an internationally comparative point of view. The latter includes to e.g. reflect on the variety of national welfare state settings that shape respective arguments of “existing UAM.”

Regarding these desiderata, it can be useful to draw from existing knowledge of comparative welfare state research to understand UAM as a “social problem” that is constantly being reified through diverse national social policy programs. The article at hand attempts to take some first steps towards such a perspective.

2 Theoretical framework, reification and research question

The existing variety of special terms for young people “under 18 years of age seeking refuge in a foreign country without an adult being responsible for them“ (Plener et al. 2017, p. 1) supports the idea that it makes sense to conceive the vast and growing number of UAM as a social rather than a merely (inter-)individual phenomenon. Following this thought, it is coherent to consider definitions of young people as UAM as a symbol of distinctly “modern” institutionalizations. For these institutionalizations, the idea of (national) welfare states (Clarke 2014) seems pivotal.

Consistently, throughout this article, we understand the finding that young people who look for a better life in another country on their own are constantly put as “Unaccompanied (Refugee/Migrant) Minors” etc. as a proof to the theoretical idea that a “UAM” represents a specific social relation, for which the modern concept of national welfare states is essential. That is to say that even only speaking of young people as UAM is related to a concept of modern (national) welfare states. Chavez and Menjivar (2010) make this very clear when they write:

“Children who migrate without their parents can be categorized in a number of ways, depending on the definitions and policies in place, as well as on the political responses to their migration. Thus, these children are often identified as juvenile aliens, unaccompanied minors, separated minors, juvenile asylum seekers, and/or refugee children, unaccompanied immigrant children, unaccompanied alien children, unaccompanied juvenile aliens, refugee children [É]. Each categorization reflects the policies and positions of receiving or transit countries regarding this phenomenon, and each triggers varied policy responses, including legal actions that can lead to immediate deportation, which are based on the technicalities of the definition used” (Chavez & Menjivar 2010, p. 73).[3]

That said, there are not only good reasons to understand UAM as a social rather than an (inter-)individual or “just human” phenomenon, but that it can also make sense to perceive UAM as a political phenomenon in a narrower sense. From such a perspective, UAM can be understood as a “social problem” that is politically constructed (Spector & Kitsuse 1977; Holstein & Miller 1993; Spector & Kitsuse 2001) through modern welfare states.[4] Taking into account various existing levels of modern “welfare state settings and practices” (Sandermann 2014), like legal definitions, organizational accountabilities, monetary and professional approaches, UAM represent a multilayered social problem. As such, “the social problem of UAM” cannot be fully addressed in this article. What can be done, however, is a comparative analysis of specific relations between young people addressed as UAM and European welfare states.

Drawing from general insights of social constructionism (Burr 2015) and its meaning for social policy development and target group Schneider & Ingram 2008; Schneider & Sidney 2009), it has to be considered that “the welfare state” does not represent a homogeneous political concept and/or empirical reality, and that there are various levels of social policy contributing to specific national welfare state settings and practices. There are reasons to assume that in a globalized world, there are even “traveling” social policies that cross national borders of welfare states (Peck and Theodore 2014; Gingrich and Köngeter 2017).

This said, it seems ambitious to comparatively explore how European welfare states relate to UAM as social problems. To do so, it feels critical to us to at least distinguish between social policies in a broader sense and welfare states in a narrower sense.

While welfare states are by definition national entities (Carke 2014), a social policy analysis that does not ignore, but analytically frame welfare states as national cases of social policies can focus on at least three levels,[5] on which social policies regularly refer to UAM as a social problem. These levels read as follows:

1 UAM are reified as a global social problem, mainly by virtue of an institutionalized perspective of the United Nations and associated organizations that frame international rights of refugees and children as well as guidelines on policies and procedures in dealing with UAM,

2 UAM are reified as a social problem on the EU level, mainly represented through EU institutions implying respective regulations and directives,

3 and, maybe most importantly, UAM are reified as a social problem on the level of national welfare states, which define and redefine UAM as a social problem through a whole range of laws, regulations, organizational and monetary instruments, and professional categorizations.

The institutions on these three levels do not only differ as such, but also in terms of how they politically reify UAM:

a) On the global policy level, the UN reify UAM as

“a person who is under the age of eighteen years, unless, under the law applicable to the child, majority is attained earlier and who is ‘separated from both parents and is not being cared for by an adult who by law or custom has responsibility to do so’.”[6]

This status of vulnerability has frequently been addressed through the UN,[7] and is acknowledged in the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC), where children seeking refugee status “whether unaccompanied or accompanied by his or her parents or by any other person” are granted the right to “receive appropriate protection and humanitarian assistance in the enjoyment of applicable rights set forth in the present Convention.”[8] In sum, the guidelines and rights framed on a global level reveal that UAM are being reified in at least two ways: as children and as refugees (Parusel 2011, pp. 147-148).

b) On the European level, the latest developments since 2013, when the absolute number of UAM entering Europe and applying for asylum across Europe started to increase dramatically, have built up a high pressure to perceive UAM as a social problem. But even before these latest developments, there had been a clear tradition to consider UAM as a certain kind of social problem “between immigration control and the need for protection.” (Parusel 2011) As opposed to the U.N.’s perspective on UAM, which above all materializes in the “Guidelines on Policies and Procedures in dealing with Unaccompanied Children Seeking Asylum,”[9] but can also be found in the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child and other documents, the EU does not only reflect on UAM as a matter of refugee´s and children’s rights, but also has to deal with the fact that the EU is a political territory divided from other political territories through borders. With reference to the latest data on UAM published by Eurostat, there are reasons to believe that at least the latest development of 100,000 UAM applying for asylum in 2015 is foremost being considered as a European social problem, as “in 2015 there were 96,500 applications in the EU-28 from unaccompanied minors.”[10] Nevertheless, the ongoing European debate on how to treat and even “distribute” refugees in Europe shows to what extent another level still trumps all other levels of the political debate: This is the level of the nation state.

c) On the national welfare state level, children who seek refuge and travel without parents represent a variety of possible social problems that, depending on the respective countries one compares, can differ in such a tremendous way that they might be even hard to compare at all. This is why it is even more important to reflect on the extent to which “UAM” is a categorization that represents a societal relation, for which the modern concept of national welfare states is essential. It mirrors directly in the bureaucratic procedure that only those children who become officially registered or apply for asylum in a country are statistically being considered as UAM.[11]

Concluding from what we have argued so far, we conceive “UAM in Europe” as a socially constructed phenomenon that refers to a very limited amount of data from individual life courses of risk-exposed children, and relates these data to multiple and multifaceted social policy frameworks that materialize on at least[12] three (global; European; national) policy levels. Reifications of UAM on these three levels can contradict each other, which makes it even more necessary to distinguish between levels when comparing the handling of UAM. For our following comparative analysis, we will focus on the national welfare state level, as we understand that it is still most influential where it comes to social policy in general, and to social policies for UAM in particular.

As we understand “welfare state settings” (Sandermann 2014) as dynamic rather than fixed structures (Lessenich 2008), a comparative investigation of UAM-related “settings” can analytically distinguish between three phases of construction, during which young people are continuously being related to national welfare states as “UAM”. These three phases read as follows:

1 During a first phase, European welfare states “receive” young people who come to Europe without any legal guardian in various ways. This is also the phase where welfare states initially construct young people as UAM – in different ways.

2 During a second phase, young people considered to be UAM are placed in care arrangements that European welfare states established in various ways to further handle these young people as UAM.

3 During a third phase, European welfare states deconstruct young people from UAM to still young, but supposedly self-sufficient people. Also here, various European welfare states supposedly differ in terms of after-care procedures etc.

By distinguishing between these three phases, we observe the social construction of UAM through European welfare states as an ongoing process. In order to analyze this process empirically, we will follow the research question: “What differences and commonalities do exist in various European welfare states in terms of how they receive young people who come to Europe without legal guardians during the initial reception phase and during long-term care arrangements for young people categorized as asylum-seeking UAM?”

3 Method and Sample: A comparative analysis of UAM constructions through 13 European welfare states

Taking seriously what we have argued so far, a decidedly comparative perspective on UAM in Europe would have to develop its own data collection methods. Gaining from more general knowledge on comparative research in social sciences, it would be the aim to collect truly comparable data first hand. This is something we cannot offer at this point.

What can be done though as a first step towards a comparative approach on UAM in European welfare states is to analyze existing data comparatively in a strict sense. That means to a) identify and comparatively resume findings from existing case studies on how single national welfare states in Europe reify young people as UAM, and b) reveal research desiderata in this respect.

To achieve this aim, we drew available information on accommodations during the initial reception phase and long-term accommodations from various research papers that focus on single European countries’ respective handling of young people as UAM. We treated the available papers as documents and interpreted the information presented on UAM accommodations as findings on moments of UAM construction across national welfare state settings. To do this, we coded the papers both deductively and inductively (Benaquisto 2008; Lockyer 2004), after which we integrated the codes into a comparative analysis tool. This tool allowed for a direct comparative description and interpretation of our findings (Palmberger & Gingrich 2010) the results of which will be presented in section 4 resp. 5 of this paper.

Some of the documents we gathered information from were papers of the special issue at hand . Moreover, we reviewed the EMN reports of 2010 and 2015, and other selected publications on UAM in European countries. However, our sample covers those countries that are represented overall in this special issue (part I, published in 2017, and part II, at hand). In total, we analyzed 32 publications on the topic (the four EMN reports counting as four texts). Where sources disagreed, we occasionally scrutinized reported findings through own internet research to double check the validity and timeliness of the provided data. In one case, we had to conduct a complementary interview to collect data.

In what follows, our perspective stays limited to findings on the programmatic level of welfare state policies, while the actual performance of “welfare state practices” (Sandermann 2014) through clerks, counselors, social workers, police and migration officers, teachers, and other “agents of the welfare state” (Jewell 2007) at the frontlines of public assistance remain largely unseen. We have to concentrate on the more general and programmatic level of welfare state settings, as the research literature we draw from mostly concentrates on this level as well.

4 Findings: The construction of UAM through 13 European welfare states

With section 2 of this paper, we analytically distinguished between three phases of UAM construction through European welfare states. (construction during intake, handling during long term care arrangements, and deconstruction during after care procedures) In what follows, we will concentrate on findings on the construction of UAM during intake and long term care arrangements. This limitation is due to the little empirical data available for the third phase, as ascertained at the end of section 2 of our paper.

4.1 How to make a UAM: The ways in which European welfare states receive young people who enter their territory without legal guardians

Young people from abroad who arrive in Europe without legal guardians only become relevant as UAM when they are officially constructed as such. Oftentimes, this happens right away during their initial reception. Here, it is essential to ascribe three characteristics to the young people: a minority status, a refugee status, and a status of being unaccompanied. All of these characteristics are important for a welfare state to distinguish UAM from other socially constructed groups as for instance adult or “regular” minor refugees (accompanied by a legal guardian), “usual” migrants accompanied by a legal guardian, or minors who are citizens of the respective nation state, but currently without a legal guardian.

The construction of UAM has to be imagined as a constantly ongoing process. However, what we assume as an initial construction phase is a crucial moment of the overall construction process. It is crucial because welfare state settings have many options of how to deal with UAM right away. These options range from already existing control and support structures that had been established for other target groups to specialized support structures tailored to UAM.

In a nutshell, there exist two different ways of assessing young people as UAM age-wise (at the border vs. during the initial reception phase), and three ways of initially accommodating young people as UAM (in dedicated reception facilities for UAM; in ordinary care facilities for children and youth; in ordinary reception facilities for refugees). If we only reflect on these two moments of initial reception and its possible differentiations, we can count 12 potential combinations of how a European welfare state might initially receive young people as UAM. Almost all of these combinations exist.

Only few sources provide an overview of the organization of the initial reception phase. One EMN report presents the reader with a short comparative overview on the stages of the asylum procedure and the organization of reception facilities (EMN 2014a: 9-10). Moreover, some articles (including those articles collected in the special issue at hand) contain such information with regard to the specific situation in a single welfare state.

Age, and, in the case where official documents are lost or the stated age is in doubt, age assessments, play a pivotal role for the construction of UAM in all European welfare states. However, welfare state settings differ in terms of how and when exactly age assessment tests are being conducted. In our sample, the majority of eight states (Austria; England; Germany; Ireland; Italy; Norway; Romania; Sweden) will have their border authorities immediately refer a young person who travels alone and just might be underage to special authorities that will check the young person’s age during the further reception process. In the other five countries of our sample (Belgium; France; Greece; the Netherlands; Switzerland), border authorities themselves will conduct age assessments right away if the declared age is in doubt. (see table 1, second column) This seemingly small difference is important, as it shows that the construction process of UAM varies among welfare states with regard to its starting point. While in the afore-mentioned eight states of our sample, there is the idea that the mere chance of dealing with a UAM is sufficient to treat young people as UAM, the other five states have their state authorities verify a UAM status first.

We interpret this as a basic pattern in the construction of UAM during the initial reception phase, as it mirrors tendencies of welfare states to either construct UAM as a social problem of refugee aid or a social problem of child welfare. In the majority of eight welfare state cases, young people who enter the country without a legal guardian are temporarily considered to be UAM under the reserve that their exact age has to be verified later on. This suggests that these welfare states construct young persons who enter the country without a legal guardian predominantly as a matter of child welfare. The other five welfare states verify the UAM status through age assessments before young people turn from cases of refugee aid into cases of child welfare. This suggests that these welfare states construct young persons who enter the country without a legal guardian predominantly as a matter of refugee aid.

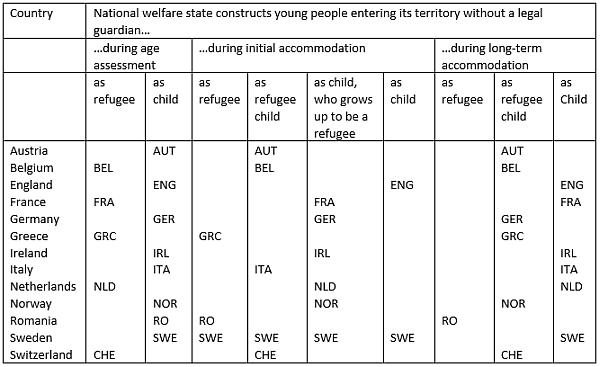

Table 1 Accommodation of asylum seeking[13] UAM during the initial reception phase

|

Country |

Age (if in doubt) is being assessed |

Asylum-seeking UAM are initially accommodated |

|

Austria |

During initial reception Source: EMN 2015a, p. 17 |

- in dedicated reception facilities for UAM Source: Heilemann 2017, p. 6 |

|

Belgium |

At the border Source: EMN 2015a, p. 17 |

- in dedicated reception facilities for UAM Source: De Graeve, Vervliet & Derluyn 2017, p. 5 |

|

England |

During initial reception Source: EMN 2015a, p. 17 |

- in ordinary care facilities for children and youth Source: EMN 2015a, p. 23; Wade 2018, p. 5 |

|

France |

At the border Source: EMN 2015a, p.17 |

- in dedicated reception facilities for UAM - in ordinary care facilities for children and youth Source: EMN 2014b, p. 24 |

|

Germany |

During initial reception Source: Zeller & Sandermann 2018, p. 11 |

- in dedicated reception facilities for UAM - in ordinary care facilities for children and youth Source: Zeller & Sandermann 2018, p. 13 |

|

Greece |

At the border Source: Fili & Xythali 2018, p. 5 |

- in ordinary reception facilities for refugees Source: Fili & Xythali 2018, p. 4 |

|

Ireland |

During initial reception Source: EMN 2015a, p. 17 |

- in dedicated reception facilities for UAM - in ordinary care facilities for children and youth Source: Arnold & Ní Raghallaigh 2017, p. 10 |

|

Italy |

During initial reception Source: EMN 2015a, p.17 |

- in dedicated reception facilities for UAM Source: Accorinti 2015, p. 63 |

|

Netherlands |

At the border Source: Zijlstra 2018, p. 5 |

- in dedicated reception facilities for UAM - in ordinary care facilities for children and youth Source: Zijlstra et al. 2018, p. 9 |

|

Norway |

During initial reception Source: EMN 2015a, p. 17 |

- in dedicated reception facilities for UAM - in ordinary reception facilities for refugees Source: Staver & Lidén 2014, p. 25 |

|

Romania |

During initial reception Source: Bejan, Curpan & Anza 2017, p. 8 |

- in ordinary reception facilities for refugees Source: Bejan, Curpan & Anza 2017, p. 10 |

|

Sweden |

During initial reception Source: EMN 2015a, p. 17 |

- in dedicated reception facilities for UAM - in ordinary care facilities for children and youth - in ordinary facilities for refugees Sources: Çelikaksoy & Wadensjö 2017, p. 9; EMN 2015a, p. 23 |

|

Switzerland |

At the border Source: Interview with Swiss experts |

- in dedicated reception facilities for UAM Source: Interview with Swiss experts |

There are three different types of accommodation of young people who are considered to be UAM during the initial reception phase. They are either accommodated in dedicated reception facilities for UAM, in ordinary care facilities for children and youth, or in ordinary facilities for refugees. These three types can theoretically be combined in seven different ways. However, our analysis shows that only five cases can be found in our sample of 13 European welfare states. (see table 1; third column) Of the investigated 13 cases, only England accommodates all UAM in ordinary care facilities for children and youth. Two welfare states (Greece; Romania) accommodate all UAM in ordinary reception facilities for refugees. Four welfare states (Austria; Belgium; Italy; Switzerland) accommodate all UAM in dedicated reception facilities for UAM, and another five welfare states (France; Germany; Ireland; the Netherlands; Norway) accommodate UAM in both dedicated reception facilities for UAM and in ordinary care facilities for children and youth, while younger UAM are mostly placed in ordinary care facilities for children and youth and older UAM are more likely to be placed in dedicated reception facilities for UAM. Finally, one welfare state initially accommodates UAM in all three types of facilities (Sweden).

We interpret these differences of initial accommodation of UAM as another facet of the afore-mentioned basic pattern in the construction of UAM during the initial reception phase. Once more, the differences mirror tendencies of welfare states to either construct UAM predominantly as a social problem of refugee aid or as a social problem of child welfare. Greece and Romania on the one hand and England on the other represent two poles that represent the whole range of how European welfare states accommodate young people who are considered to be UAM during their initial reception phase: The English welfare state directly refers all UAM to ordinary care facilities for children and youth, which suggests that the English welfare state constructs young persons who enter the country without a legal guardian predominantly as a matter of child welfare. Greece and Romania, on the opposite end, construct them as a matter of refugee aid, which mirrors in the young people’s initial accommodation at ordinary reception facilities for refugees. However, ten out of the 13 European welfare states of our sample have to be located in between these two opposing poles. All ten of them organized a specific structure of reception facilities for UAM, and four of them (Austria; Belgium; Italy; Switzerland) even rely on these facilities exclusively where it comes to initial accommodations of UAM. Where the English welfare state constructs UAM as “children”, and the Greek and Romanian welfare states seem to construct them predominantly as “refugees”, the welfare states of Austria, Belgium, Italy and Switzerland seem to most decidedly approach them as “refugee children”, while the French, German, Irish, Dutch and Norwegian welfare states seem less decided and construct young people who enter the country without a legal guardian as children, who become more refugee-like when they grow older though. The Swedish welfare state differs from all of these constructions as it seems to combine all possible facilities for initial accommodation in a rather pragmatic way.

4.2 How to keep a UAM a UAM: The ways in which European welfare states long-term accommodate young people who enter their territory without legal guardians

Arguably, young people are not only constructed as “UAM” during the initial reception phase that we just looked at. They are being permanently reconstructed as UAM over the course of their long-term reception of services. In this sense, it is fruitful to also compare the ways in which European welfare states provide long-term accommodation for these young people. For pragmatic reasons of research, at this point, we will focus on cases of “asylum-seeking UAM”[14] only.

Table 2 Long-term accommodations of (asylum seeking)[15] UAM

|

Country |

Types of long-term accommodation |

|

Austria |

- Primarily: Dedicated group homes for UAM - Foster families Source: Heilemann 2017, pp. 8-9 |

|

Belgium |

- Primarily: Large dedicated reception centers for UAM - Dedicated group homes for UAM - Standard group homes for children and youth - (Semi-)independent living arrangements - Foster families (applies to young people who had previously been accommodated at specified reception centers for UAM, and who are younger than 14 years or are categorized as having special needs, such as (pregnant) girls, young people who suffer from psychological disorders) Source: De Graeve, Vervliet & Derluyn 2017, p. 6; EMN 2015a, p. 23 |

|

England |

- Primarily: Foster families - (Semi-)independent living arrangements (applies to some 15-18 year-olds) - Standard group homes for children and youth - Sources: EMN 2015a, p. 23; Wade 2018, pp. 4-5 |

|

France |

- Primarily: Standard group homes for children and youth - (Semi-)independent living arrangements - Foster families Source: EMN 2015a, p. 23; Frechon & Marquet 2018, pp. 10-11 |

|

Germany |

- Primarily: Dedicated group homes for UAM - Standard group homes for children and youth - (Semi-)independent living arrangements - Foster families Sources: EMN 2015a, p. 23; Zeller & Sandermann 2018, pp. 14 |

|

Greece |

- Primarily: Large dedicated reception centers[16] for UAM Source: Fili & Xythali 2018, pp. 9-10 |

|

Ireland |

- Primarily (92%): Foster families - Standard group homes for children and youth Source: Arnold & Ní Raghallaigh 2017, pp. 7, 10; EMN 2015a, p. 23 |

|

Italy |

- Primarily: Foster families - Dedicated group homes for UAM - Standard reception facilities for refugees Source: Giovanetti 2018, pp. 13-14 |

|

The Netherlands |

- Primarily (33%): Foster families with families of the same cultural background - Dedicated group homes for UAM (applies to 14-16 year-olds, who are assumed to be more self-reliant) - Campuses [large dedicated reception centers for UAM] (applies to some 16-18 year-olds) - Protected, dedicated group homes for victims of human trafficking (if applicable) Source: Zijlstra et al. 2018, pp. 8-11 |

|

Norway |

- Primarily: Dedicated group homes and (semi-)independent living arrangements run on behalf of UDI [Norwegian Directorate of Immigration] - Dedicated group homes run by Bufetat [Office for Children, Youth and Family Affiars] and child welfare services (applies to young people who are younger than 15 years or are categorized as having special needs, such as (pregnant) girls, young people who suffer from psychological disorders, victims of human traficking) - Foster families (only applies to yet settled young people who are younger than 15 years) Sources: Lidén, Gording Stang & Eide 2017, p. 12; Staver & Lidén 2014, pp. 23-25 |

|

Romania |

- Primarily: Standard accommodation facilities for refugees - Kinship care (or care through other acquaintances) - Host families Source: Bejan, Curpan & Anza 2017, pp.7-8, 10, 12 |

|

Sweden |

- Primarily: Standard group homes for children and youth - Kinship care (or care through other acquaintances) - Foster families (applies to younger children) Source: Çelikaksoy & Wadensjö 2017, p. 9; EMN 2015a, p.23 |

|

Switzerland |

- Primarily: Dedicated group homes for UAM - Large dedicated reception centers for UAM - Foster families - Kinship care (if there are relatives) - Source: Keller, Mey & Gabriel 2017, pp. 2, 14 |

As illustrated in table 2, there are various types of long-term accommodation to compare. There exist dedicated group homes for UAM, large dedicated reception centers for UAM, standard group homes for children and youth, (semi-)independent living arrangements, foster families, kinship care, host families and finally standard reception facilities for refugees that UAM are accommodated at. In sum, long-term accommodations for young people who are constructed as UAM differ even more among European welfare states than accommodations during the initial reception phase (see section 4.1).

Regarding overall commonalities, there are four general patterns to identify: Firstly, all European welfare states of our sample provide a mix of long-term accommodations for young people constructed as UAM. Secondly, foster families are a format that is broadly used for the long-term accommodation of UAM, the only exception to this rule being Greece and Romania, while foster care especially applies to the relatively young UAM. Thirdly, five European welfare states of our sample (Austria; Belgium; Greece; the Netherlands; Switzerland) established large, dedicated reception centers to long-term accommodate young people as UAM. Finally, three of the 13 welfare states of our sample (Belgium; the Netherlands; Norway) established long-term accommodations for a special group of young people subcategorized as “UAM with special needs” – usually comprising of (pregnant) girls, young people who suffer from psychological disorders and victims of human trafficking.

To reflect on commonalities and differences alike, it is helpful to zoom in on how the 13 states of our sample long-term accommodate UAM primarily. (see table 2) Through this, more patterns begin to show. There are four European welfare states (Austria; Germany; Norway; Switzerland) that long-term accommodate UAM primarily at dedicated group homes for UAM. Then, there are another 4 states (England; Ireland; Italy; the Netherlands) that long-term accommodate UAM primarily with foster families. A third grouping of two European welfare states (France; Sweden) long-term accommodates UAM primarily at standard group homes for children and youth. Fourthly, there are two states (Belgium; Greece) that long-term accommodate UAM primarily at large dedicated reception centers for UAM. Finally, there is the state of Romania, where UAM are primarily long-term accommodated at standard accommodation facilities for refugees.

One might interpret these differences and commonalities between European welfare states regarding the long-term accommodation of UAM as another facet of the above-described tendencies of welfare states to either construct UAM predominantly as a social problem of refugee aid or as a social problem of child welfare. If ones does so, however, the patterns of long-term accommodation do not simply repeat those groupings of European welfare states that we could show for the initial reception phase (see section 4.1): While Romania primarily accommodates UAM at standard accommodation facilities for refugees and represents an extreme pole of constructing UAM as a social problem of refugee aid, there are six welfare states (England; France; Ireland; Italy; the Netherlands; Sweden) that primarily integrate young people constructed as UAM into regular institutions of child and youth care, may that be foster families or standard group homes for children and youth, and therefore seem to represent the other pole of constructing UAM predominantly as a matter of child welfare. Yet, it is interesting that e.g. in France, UAM are primarily accommodated at standard group homes for children and youth while a foster family would be the preferred care arrangement for a French minor of the same age. This contradicts the first impression of a consistent integration of UAM into the countries’ regular care structures, i.e. a predominant perspective of child welfare where it comes to constructing UAM as a social problem. What can be said though is that there is another grouping of six European welfare states (Austria; Belgium; Germany; Greece; Norway; Switzerland) that primarily accommodate UAM in formally dedicated institutions. There are vast differences among these institutions, not only in terms of their organizational structure (vs.) but noticeably also in terms of their professional qualities. However, it is striking that all of these countries obviously constructed UAM as a specific social problem that differs even formally from problems of “ordinary refugee aid” and from problems of “ordinary child welfare.” In the cases of Austria, Germany and Greece, this differentiation might be explained by the mere number of young people who entered the countries and were constructed as UAM here. But that explains for only three of the six cases that have to be explained, and finds its counter-argument with the case of Sweden, the European welfare state that (given the countries’ size) clearly ranks number 1 in hosting young people who are being constructed as UAM.

5 Summary: Differences and commonalities of how European welfare states construct young people as “Unaccompanied Minors”

In what follows, we will sum up the above-described findings against the background of contemporary welfare state theory. To do that, it is important to reflect that the most part of welfare state theories concentrates on analyzing empirical phenomena that can be reified as social insurance benefits rather than public assistance issues. This is particularly true where it comes to comparative perspectives. Yet the given case of accommodation settings for young people categorized as UAM is clearly to be considered as a case of public assistance. Therefore, e.g., Esping-Andersen’s (1990) prominent and repeatedly tested theory of Western welfare regimes is of limited value for our empirical findings. It can be stated that, in the case of the organization of age-assessment, initial and long-term accommodation for UAM, the differentiation of public services does not follow a clear typology of liberal, conservative and social democratic welfare states as Esping-Andersen demonstrated it for social insurance systems.

Instead, a constructionist approach of doing social problems as we sketched it in section 2 of this paper felt more valuable to interpret our findings. This approach was promising as, obviously, European welfare states differ in how they apply the very term “UAM” to young people, and, along with that, organize the handling of young persons as UAM. We adapted the social problems approach in binary fashion to distinguish between constructions of UAM as matters of refugee aid vs. matters of child welfare.

Given the complexity of our results and the limited space of this paper, we will present our conclusory results with another, strictly comparative table (see table 3). It represents the whole variety of paths that European welfare states take to construct “their UAM.”

Table 3: The first phases of UAM construction through 13 European welfare states

Visibly, the 13 states of our sample differ greatly in terms of how they construct young people who enter their territory without a legal guardian as UAM. These differences rely on the mutable verification of three central characteristics of the UAM status (refugee, under age, unaccompanied), and prove for two facts:

1 Nation states are still most important players in the inter- and supranational challenge of addressing UAM as a social problem. That is why, from a comparative point of view, there are only very few commonalities among European welfare states as far as their constructions of young people as UAM go.

2 There are in fact tendencies of welfare states to either construct UAM predominantly as a social problem of refugee aid or as a social problem of child welfare. However, there are only three pairs of countries that construct UAM exactly alike.

Regarding result no. 2, there are

a) the Belgian and the Swiss welfare state models, which both built up a specialized structure to precisely address UAM as “refugee children”, and combine this with a rather high threshold of entering the system.

b) the German and the Norwegian welfare state models, which both built up a specialized structure to precisely address UAM as “refugee children”, and combine this with a rather low threshold of entering the system.

c) the French and the Dutch welfare state models, which both integrate UAM predominantly into their ordinary child welfare structures, and combine this with a rather high threshold of entering the system.

d) the English and the Swedish welfare state models, which both integrate UAM predominantly into their ordinary child welfare structures, and combine this with a rather low threshold of entering the system.

All of these results are not to be mistaken as evaluations of the quality of the compared systems. “Good practices” cannot to be directly determined from our analysis. This is because our research has not taken into account further contexts of welfare state development, like for example geographical circumstances and the historical development of the 13 states’ welfare services. Furthermore, it did not include the actual practices of clerks, counselors, social workers etc. constructing UAM at the frontlines of public services (see section 3).

What it can provide though is a first and limited, decidedly comparative perspective on UAM constructions across European welfare states. For now, it shows most notably that welfare states across Europe are far from a complementary strategy for defining and organizing the social problem of UAM in Europe. From the point of view of a young person who enters the continent without a legal guardian and hopes for protection in Europe, this probably feels very arbitrary.

References

Accorinti, M. (2015). Unaccompanied Foreign Minors in Italy: Procedures and Practices. Review of History and Political Science 3(1), 60-72.

Arnold, S. & Ní Raghallaigh, M. (2017). Unaccompanied Minors in Ireland: Current Law, Policy and Practice. Social Work and Society 15(1), 1-16.

Arts, W. & Gelissen, J. (2002). Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism or More? A State-of-the-art Report. Journal of European Social Policy 12(2), 137-158.

Bahle, T., Pfeifer, M. & Wendt, C. (2010). Social Assistance. In: Castles, F. G., Leibfried, S., Lewis, J., Obinger, H. & Pierson, C. (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of the Welfare State (pp.448-461). Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.

Bambra, C. (2007). Going Beyond the Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism: Regime Theory and Public Health Research. Epidemiol Community Health 61, 1098–1102.

Bejan, R., Curpan, A. I. & Amza, O. (2017). The Situation of Unaccompanied Minors in Romania in the Course of Europe’s Refugee Crisis. Social Work and Society 15(1), 1-20.

Benaquisto, L. (2008). Codes and Coding. In: Given, L.M. (Ed.). The SAGE Encyclopedia of Qualitative Research Methods (pp.85-88). Volume 1. Los Angeles, CA et al.: Sage.

Bonoli, G. (1997). Classifying Welfare States: A Two-dimension Approach. Journal of Social Policy 26(3), 351-72.

Burr, V. (2015). Social Constructionism. Third edition. London and New York: Routledge.

Celikaksoy, A. & Wadensjö, E. (2016). Mapping Experiences and Research about Unaccompanied Refugee Minors in Sweden and Other Countries. IZA Discussion Papers, No. 10143.

Çelikaksoy, A. & Wadensjö, E. (2017). Policies, Practices and Prospects: Unaccompanied Minors in Sweden. Social Work and Society 15(1), 1-16.

Chavez, L. & Menjivar, C. (2010). Children Without Borders. A Mapping of the Literature on Unaccompanied Migrant Children in the United States. Migraciones Internationales 5(3), 71-111.

Clarke, J. (2014). The End of the Welfare State? The Challenges of Deconstruction and Reconstruction. In: Sandermann, P. (Ed.), The End of Welfare as We Know It? Continuity and Change in Western Welfare State Settings and Practices (pp.19-34). Opladen/Berlin/Toronto: Barbara Budrich.

European Migration Network (2010). Policies on Reception, Return and Integration Arrangements for, and Numbers of, Unaccompanied Minors – An EU Comparative Study. Brussels: European Commission.

European Migration Network (2014a). The Organisation of Reception Facilities for Asylum Seekers in different Member States – European Migration Network Study 2014. Brussels: European Commission.

European Migration Network (2014b). Policies, Practices And Data on Unaccomanied Minors in 2014. Study conducted by the French Contact Point for the European Migration Network (EMN). Brussels: European Commission.

European Migration Network (2015a). Policies, Practices and Data on Unaccompanied Minors in the EU Member States and Norway – Synthesis Report. Brussels: European Commission.

European Migration Network (2015b). Policies, Practices and Data on Unaccompanied Minors in the EU Member States and Norway – Annexes to the Synthesis Report. Brussels: European Commission.

Esping-Andersen, G. (1990). The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Evans, T. & Harris, J. (2004). Street-Level Bureaucracy, Social Work and the (Exaggerated) Death of Discretion. British Journal of Social Work 34(6), 871-895.

Ferrera, M. (1996). The “Southern” Model of Welfare in Social Europe. Journal of European Social Policy 6(1), 17–37.

Ferrara, P., et al. (2016). The “Invisible Children”: Uncertain Future of Unaccompanied Minor Migrants in Europe. The Journal of pediatrics 169(6), 332-333.

Fili, A. & Xythali, V. (2018). The Continuum of Neglect: Unaccompanied Minors in Greece. Social Work and Society, 15(2), 1-15

Garvik, M., Paulsen, V. & Berg, B. (2016). Barnevernets rolle i bosetting og oppfølging av enslige mindreårige flyktninger. [The Role of Child Welfare in the Resettlement of UAM] Trondheim: NTNU Samfunnsforskning.

Gingrich, L. G. & Köngeter, S. (Eds.) (2017). Transnational Social Policy. London & New York: Routledge

Giovannetti, M. (2018). Reception and Protection Policies for Unaccompanied Foreign Minors in Italy. Social Work and Society, 15(2), 1-23

De Graeve, K., Vervliet, M. & Derluyn, I. (2017). Between Immigration Control and Child Protection. Unaccompanied Minors in Belgium. Social Work and Society 15(1), 1-13.

Heilemann, S. (2017). The Accommodation and Care System for Unaccompanied Minors in Austria. Social Work and Society 15(1), 1-18.

Holstein, J. A. & Miller, G. (1993). Social Constructionism and Social Problem Work. In: Holstein, J. A. & Miller, G. (Eds.), Reconsidering Social Constructionism. Debates in Social Problems Theory (pp.131-152). New York: Aldine de Gryter.

Jewell, C. J. (2007). Agents of the Welfare State. How Caseworkers Respond to Need in the United States, Germany, and Sweden. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Kaukko, M. & Wernesjö, U. (2016). Belonging and Participation in Liminality: Unaccompanied Children in Finland and Sweden. Childhood 24(1), 7-20.

Keller, S., Mey, E. & Gabriel, T. (2017). Unaccompanied Minor Asylum-Seekers in Switzerland – A Critical Appraisal of Procedures, Conditions and Recent Changes. Social Work and Society 15(1), 1-17.

Leibfried, S. (1992). Towards a European Welfare State? On Integrating Poverty Regimes into the European Community. In Ferge, Z. & Kolberg, J. E. (Eds.), Social Policy in a Changing Europe (pp. 245-280). Frankfurt am Main: Campus Verlag.

Lessenich, S. (2008). Wohlfahrtsstaat. In: Bauer, N., Korte, H., Löw, M. & Schroer, M. (Eds.), Handbuch Soziologie (pp.483-498). Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Lidén, H., Gording Stang, E. & Eide, K. (2017). The Gap Between Legal Protection, Good Intentions and Political Restrictions. Unaccompanied Minors in Norway. Social Work and Society 15(1), 1-20.

Lidén, G. & Nyhlén, J. (2016). Structure and Agency in Swedish Municipalities’ Reception of Unaccompanied Minors. Journal of Refugee Studies 29(1), 39-59.

Lipsky, M. (2010). Street-Level Bureaucracy. Dilemmas of the Individual in Public Services. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Lockyer, S. (2004). Coding Qualitative Data. In: Lewis-Beck, M.S., Bryman, A., & Futing Liao, T. (Eds.), The SAGE Encyclopedia of Social Science Research Methods. Volume 1 (pp. 137-138). Los Angeles, CA et al.: Sage.

Maynard-Moody, S. & Musheno, M. (2003). Cops, Teachers, Counselors: Stories from the Front Lines of Public Service. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Orme, J. & Briar-Lawson, K. (2010). Theory and Knowledge about Social Problems to Enhance Policy Development. In: Shaw, I. et al. (Eds.), The Sage Handbook of Social Work Research. Los Angeles: Sage.

Palmberger, M. & Gingrich, A. (2014). Qualitative Comparative Practices: Dimensions, Cases and Strategies. In: Flick, U. (Ed.). The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Data Analysis (pp. 94-108). Los Angeles, CA et al.: Sage.

Parusel, B. (2011). Unaccompanied Minors in Europe – Between Immigration Control and the Need for Protection. In: Lazaridis, G. (Ed.), Security, insecurity and migration in Europe (pp.139-160). Farnham: Ashgate.

Parusel, B. (2017). Unaccompanied Minors in the European Union – Definitions, Trends and Policy Overview. Social Work & Society 15(1), 1-15.

Peck, J. & Theodore, N. (2014). On the Global Frontier of Post-Welfare Policymaking: Conditional Cash Transfers as Fast Social Policy. In: Sandermann, P. (Ed.), The End of Welfare as We Know It? Continuity and Change in Western Welfare State Settings and Practices (pp.53-69). Opladen, Toronto, Berlin: Barbara Budrich Publishers.

Plener, P. L., Groschwitz, R. C., Brähler, E., Sukale, T., & Fegert, J. M. (2017). Unaccompanied Refugee Minors in Germany: Attitudes of the General Population Towards a Vulnerable Group. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 26(3), 1-10.

Sandermann, P. (Ed.). The End of Welfare as We Know It? Continuity and Change in Western Welfare State Settings and Practices. Opladen, Toronto, Berlin: Barbara Budrich Publishers.

Schneider, A. & Ingram, H. (2008). Social Constructions in the Study of Public Policy. In: Holstein, J. (Ed.), Handbook of Constructionist Research (pp. 189-211). New York: Guildford Publications

Schneider, A. & Sidney, M. (2009). What is Next for Policy Design and Social Construction Theory? The Policy Studies Journal 37(1), 103-119.

Spector, M. & Kitsuse, J. I. (1977). Constructing Social Problems. Menlo Park: Cummings Publishing.

Staver, A. & Lidén, H. (2014). Unaccompanied Minors in Norway: Policies, Practices and Data in 2014. Norwegian National Report to the European Migration Network. Oslo: Institutt for samfunnsforskning.

UNHCR (1994). Refugee Children: Guidelines on Protection and Care. Geneva: Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees.

UNHCR (1997). Guidelines on Policies and Procedures in Dealing with Unaccompanied Children Seeking Asylum. Geneva: Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees.

UNHCR

& Unicef (2014). Safe and Sound: What States Can Do to Ensure Respect for

the Best Interests of Unaccompanied and

Separated Children in Europe. Brussels, New York: UNHCR Bureau of

Europe & United Nation’s Children Fund.

Wade, J. (2018). Pathways Through Care and After: Unaccompanied Minors in England. Social Work and Society 15(2), 1-15.

ZiJlstra, E, Rip, J., Beltman,D., van Os, C., Knorth, E. J. & Kalverboer, M. (2018). Unaccompanied minors in the Netherlands: Legislation, Policy, and Care. Social Work and Society 15(2), 1-19.

Author´s Address:

Prof. Dr. Philipp Sandermann

Leuphana University of Lüneburg

Universitätallee 1

21335 Lüneburg, Germany

+49(0)41316772381

sandermann@leuphana.de

Author´s Address:

Dr. Onno Husen

Leuphana University of Lüneburg

Universitätallee 1

21335 Lüneburg, Germany

+49(0)41316772386

husen@leuphana.de

Author´s Address:

Prof. Dr. Maren Zeller

Trier University

Universitätsring 15

54296 Trier, Germany

+49(0)6512012368

zeller@uni-trier.de