Unaccompanied minors in the Netherlands: Legislation, policy, and care

Elianne Zijlstra, Study Centre on Children, Migration and Law, University of Groningen

Jet Rip, Study Centre on Children, Migration and Law, University of Groningen

Daan Beltman, Study Centre on Children, Migration and Law, University of Groningen

Carla van Os, Study Centre on Children, Migration and Law, University of Groningen

Erik J. Knorth, Special Needs Education and Youth Care, University of Groningen

Margrite Kalverboer, Study Centre on Children, Migration and Law, University of Groningen

1 Introduction

During the last few years, the Netherlands have seen a high influx of refugees entering the country, among them are UAM. In Dutch policy, an UAM is defined as a person “who was under 18 on arrival in the Netherlands, whose country of origin is outside the European Union, and who travelled to the Netherlands without a parent or other person exercising authority of the child” (Government 2016). In accordance with international academic studies, UAM in the Netherlands are vulnerable (Jakobsen/Demott/Heir 2014; Jensen/Fjermestad/ Granly/Wilhelmsen 2015; Vervliet/Meyer Demott/Jakobsen/Broekaert/Heir/Derluyn 2014). Some show severe emotional problems such as depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress (Bean/Eurelings-Bontekoe/Spinhoven 2007a; Bean/Derluyn/Eurelings-Bontekoe/Broekaert/ Spinhoven 2007b; Reijneveld/De Boer/Bean/Korfker 2005). For reasons of their vulnerability, special care and attention must be paid to protect the development of these children.

In this contribution, we will give insight into the legal framework and the reception policies and practices concerning UAM in the Netherlands. First, we present basic data on UAM in the Netherlands. Second, we describe some major differences between the UAM and Dutch peers. Third, we inform on the legal framework of UAM who make a request for legal residence in the Netherlands. Fourth, we give insight in the way UAM are sheltered in the Netherlands and how they experience the quality of these care facilities. We conclude with a discussion, including recommendations for practice and research.

2 Basic data on unaccompanied minors in the Netherlands

At the end of 2015, 6,099 UAM were registered in the Netherlands (Nidos, personal communication, 24 August 2016). The ethnic background of children registered for guardianship is heterogeneous; they are coming from 85 different countries (Nidos 2016).

During recent years, there has been a large increase of the number of UAM entering the Netherlands, resulting in the quadrupling of asylum applications of UAM. Following, an overview is provided of the basic data from 2008 through 2015.

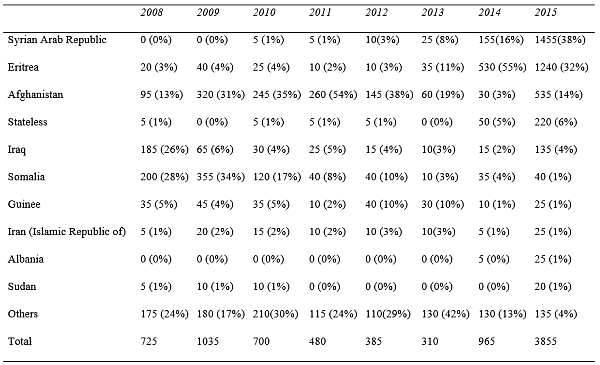

In 2015, the Netherlands counted 3,855 asylum applications that were lodged by UAM (see table 1). This is 6.6% of the total number of asylum applications in the Netherlands (58,880[1]) (Eurostat 2016a). Most children came from the Syrian Arab Republic (hereafter: Syria) (38%), Eritrea (32%) and Afghanistan (14%). Over the years, the top three countries of origin slightly changed; from Somalia, Iraq and Afghanistan in 2008 to Syria, Eritrea and Afghanistan in 2015. Afghan children have been coming during the whole period. From 2013, an ongoing increase in the number of Eritrean and Syrian children is observed (see table 1).

Table 1 The Netherlands, 2008-2015: Asylum applications considered to be unaccompanied minors by country of origin (Eurostat, 2016b)[2]

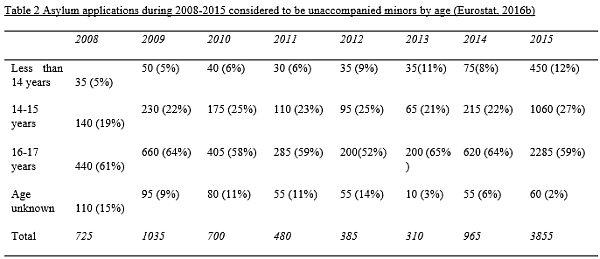

In 2015, most children were sixteen or seventeen years old (59%); however, 450 UAM under the age of fourteen applied for asylum in the Netherlands. Over the years, most UAM were sixteen or seventeen years old, followed by fourteen- and fifteen-years old. The smallest age group represented children younger than fourteen. Table 2 shows that the division between the age groups remained relatively stable from 2008 until 2015.

Table 2 Asylum applications during 2008-2015 considered to be unaccompanied minors by age (Eurostat, 2016b)

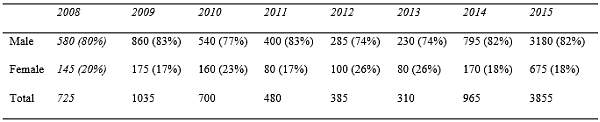

Children who applied for asylum in the Netherlands in 2015 were predominantly male (82%). The male/female ratio of child applicants was mostly similar throughout the 2008 to 2014 period (see table 3).

Table 3 Asylum applications during 2008-2015 considered to be unaccompanied minors by gender (Eurostat, 2016b)

In what follows from here on, the living circumstances of UAM in terms of health and education of UAM will be highlighted. Throughout the section, we will compare these circumstances to those circumstances that Dutch children of the same age live in. We start with a description of how the guardianship is arranged.

2.1 Guardianship

For every child in the Netherlands, there has to be a person or institution taking custody of the child. This is either the child’s parent(s) or another type of legal guardian (Civil Code (CC), Art. 1:245). When parents or caregivers are not available or able to take care of the child, the family court appoints a guardian (CC, Art. 1: 295). In most cases, someone from the family or social network of the child may be granted guardianship, otherwise youth care will provide for a guardian. For UAM from abroad, there is a separate institution – the Nidos Foundation (Foundation for Protection of Young Refugees; hereafter Nidos) – that is awarded with temporary child custody (CC, Art. 1:253r). Nidos is the Dutch guardianship institution for minor refugees, asylum seekers, and undocumented migrants. All guardians have the same obligations and responsibilities that parents have (CC, Art. 1: 303) (Goeman et al. 2011, pp. 15-18).

Since UAM flee to the Netherlands without their parents, on arrival they are placed under guardianship of Nidos until their eighteenth birthday. The central tasks in relation to guardianship are: to act in the best interests of the child, to create a safe and supportive environment for the child, and to stimulate the development of a strong social network in the Netherlands (Goeman et al. 2011; Spinder/Van Hout 2008) to ensure the child’s participation in every decision that affects the child, to advocate for the rights of the child, to be a bridge between and focal point for the child and other actors involved, and to ensure the timely identification and implementation of a durable solution regarding the respective child’s living environment and future perspective (Goeman et al. 2011). For children younger than sixteen, and vulnerable children, the guardian is always present during the interviews with the migration authorities. In other cases, the guardian may seek for other solutions for support (Nidos, personal communication, 24 August 2016, 3 October 2016). The guardian usually delegates daily care of the UAM to reception services (see below).

Formally, each guardian has a maximum of 20 UAM under his or her responsibility, but in practice, with the increased number of UAM in 2015, this has been raised to, on average, 23.5 children per full time working guardian (Nidos, personal communication, 24 August 2016, 3 October 2016). On average, the guardian visits the UAM once every two to three weeks (Kalverboer/Zijlstra/Van Os/Zevulun/Ten Brummelaar/Beltman 2016).

The future of the child (return to the country of origin or stay in the Netherlands) is an important element in the support children receive in guardianship. At an early stage, the guardian will discuss this future perspective with the child and his or her social network (Nidos 2016).

To ensure the safety and development of the UAM, the guardian makes a plan with the child about his/her future. Attention is paid to the strengths and developmental tasks, including the increase of independency of the UAM as they near adulthood (De Ruijter de Wildt et al. 2015; Nidos 2016). This approach is sometimes difficult for the UAM because they are not used to reflecting on their behavior and to give their opinion about their own life plans (Goeman/Van Os 2013).

UAM appreciate the personal relationship they have with their guardian: the children indicate they can share their worries with their guardian, they undertake leisure activities and they receive practical support. Reasons why UAM are not satisfied with their guardians are related to a higher need for support, few contacts between the guardian and the child, too much attention to the possible return, and little understanding about the current uncertain situation (Kalverboer et al. 2016; Staring/Aarts 2010). Overall, children seem to miss parental support compared to Dutch same-age peers.

2.2 Health

There is evidence that UAM struggle with more stressful life events, including internalizing problems and traumatic stress reactions in comparison with accompanied children and Dutch adolescents (Bean et al. 2007b). Bean et al. (2006) assessed that 57.8% of their sample of UAM (N=920) were in need of mental health care, whereas only 8.2% of Dutch adolescents were. It is worrying that almost half of the children in the sample report that they feel that their needs for mental health care are unmet.

In general, UAM have legal access to (mental) health services, irrespective of their residence status. In practice, guardians sometimes face difficulties to have their pupil’s mental health problems taken seriously by the health service suppliers of the large scaled reception centers (Nidos, personal communication, 6 October 2016).

UAM can use most services provided in the Youth Act (Art. 1.3, section 1). However, for undocumented children who have no legal residence status, there are deviations from these rules. There are more restrictions in the regular Youth Care System for undocumented children to be placed in family foster care, and the assessment of the need of psychosocial care has to be renewed every six months, instead of the regular twelve months for Dutch children (Youth Act Decree [Besluit Jeugdwet], Art. 2.1, section 2 and 3). For UAM under the guardianship of Nidos who stay in foster families, those restrictions have limited impact.

2.3 Education

In the Netherlands, UAM, irrespective of their residence status, have the right to receive an education. In consultation with the municipality and school boards, a suitable place – in either primary, secondary, or vocational education – needs to be found. The municipality where the child stays is responsible for the school accommodation (Buisman et al. 2016).

Primary education for children can take place in an asylum-seeking center as well as in a ‘regular’ primary school. Children start in specific language classes where they learn Dutch and from there they move to regular education. In regular education, attention is also paid to mastering Dutch and learning about Dutch culture.

Children who on arrival are at the age of secondary education (12 years) will start in an ‘Internationale Schakel Klas’ [International Transition Class] (ISK) where they can stay for a maximum of two years (Minister and State secretary of Education, Culture and Science 2015). With a large focus on language education (80%) in the ISK, children will be prepared for regular education (VNG 2016). By mastering a sufficient level of the Dutch language, the child can attend regular education (LOWAN 2016). There are worries about the quality of education for asylum-seeking children. For instance, teachers are not always sufficiently trained to teach illiterate people (Minister and State secretary of Education, Culture and Science 2015).

3 Legal Framework and Policy

In this section, we provide an overview of the legal framework and policy (based on the: Aliens Act 2000, Aliens Decree 2000, Aliens Circular 2000, and Aliens Regulation 2000) concerning UAM who request legal residence in the Netherlands. UAM in the Netherlands who ask for protection have to apply for asylum at the Immigration and Naturalization Service (IND), the executive organization that implements Dutch migration law on behalf of the State Secretary of Security and Justice, who formally takes the decision on applications.

3.1 Arrival procedure

Upon arrival, UAM have to report themselves to the immigration authorities and make a request for asylum at an application center. If the children have family members residing in another EU member state, they will, according to the EU’s family reunification directive, be expelled to that member state where they may continue the asylum procedure, except when the expulsion would not be in the best interests of the child.

In case the IND cannot establish the minor status, as no proof of age is available, an age assessment is offered to the child, which is conducted on the basis of a collarbone and wrist x-ray. Only if the test clearly indicates that the child is of age, he or she will be treated as an adult. If the age assessment is refused, this may not have implications for the substantive assessment of the asylum request (District court, 4 April 2014), other than that consequently the person will be further treated as an adult.

3.2 Asylum procedure

After the registration process, the child enters a so-called ‘rest and preparation period’ for a minimum of three weeks. At the moment, this period may take more than a year. During this period, UAM are paired with a lawyer and may voluntarily participate in a medical examination to determine if they are mentally and physically fit to be interviewed in the asylum procedure.

The asylum procedure consists of two possible routes: the general, ‘fast’ asylum procedure [Algemene Asielprocedure, AA], which takes eight days; and the extended asylum procedure [Verlengde Asielprocedure, VA], which may take six months but can be extended up to fifteen months. On average 70% of the cases are dealt with in the AA-procedure. Applications for asylum are referred to the VA-procedure when the IND needs more time to come to a decision, for instance if independent medical, forensic or child-related expertise is requested.

Following the application for asylum, the asylum procedure starts with a first interview, mainly concerning the child's identity, nationality, family members, and the journey to the Netherlands (day 1). Officers who have had training in interviewing children conduct these interviews. Children below the age of twelve are interviewed in child-friendly rooms. During the interview, a lawyer may be present. Subsequently, the report of the interview is discussed with the lawyer and afterwards the lawyer may submit corrections in the report to the IND (day 2). The child is then interviewed on the accounts of the flight (day 3), after which, the child discusses the interview report with the lawyer again, who might submit corrections on this report as well (day 4). Then, the IND decides to continue the general procedure [AA] or to refer the case to the extended procedure [VA] (day 5).

If the fast procedure is continued, the IND either decides to grant a residence permit on asylum grounds or takes a draft (intended) decision [voornemen] to reject the application. The lawyer has one day to submit a response to the draft decision (day 6). Finally, the IND takes the final decision, either to grant a residence permit or to reject the application (day 7 or 8). After the decision, the child's lawyer may file an appeal at the district court. As a last resort, the district court’s judgment may be appealed at the Council of State. A judge may find that the decision was not lawfully taken, which leads to the possibility for the IND to make a new decision or to appeal the judgment at the Council of State.

Substantively, the IND assesses whether an UAM can be considered as a refugee – that is, whether the child needs to be protected against inhumane or degrading treatment or indiscriminate violence in situations of armed conflict. The IND’s assessment entails the credibility of the child's accounts, including the statements on identity, nationality, and country of origin and reasons of flight. The child must convince the IND of a fear of persecution or of a real risk of inhumane or degrading treatment or indiscriminate violence in situations of armed conflict in the country of origin. If that is the case, a residence permit on asylum grounds may be granted. UAM who receive a residence permit can opt for family reunification if they have family members in the country of origin or elsewhere. If the IND is insufficiently convinced of the credibility of the child's accounts or finds that the child can receive protection in the country of origin or in a third country, the application is rejected.

Before or during an asylum procedure, it may come to light that the child is a victim of or witness to human trafficking or victim of child abduction. The Netherlands has special policy regulations regarding this group of migrants who may, under specific conditions, receive a temporary residence permit on these grounds (apart from a possible asylum claim).

If the IND rejects the application, a return decision will be taken. In this decision, the IND demands the child to leave the Netherlands within 28 days.

3.3 Return or ‘no fault of your own’ procedure

Until June 2013, UAM who were rejected could receive a temporary residence permit, specifically meant for UAM, which was valid up to the age of eighteen. This permission was only available for children for whom no suitable accommodation and care could be found in the country of origin. This policy was abolished in 2013 because the State Secretary found that with the residence permit, the UAM got the idea that they could stay in the Netherlands permanently, although they only received a temporary residence permit until they became of age (Parliamentary paper of the Lower House 2011-2012, 27062, no. 75, p. 1).

In case the request for a residence permit is rejected and after exhaustion of all legal means, the child's stay in the Netherlands becomes irregular. If those irregularly staying children are willing to return voluntarily to the country of origin, they must cooperate with the Dutch Repatriation and Departure Service (DT&V). Voluntary return of UAM takes place only on a small scale (Nidos, personal communication, 24 August 2016). From 1 June 2013 to 1 August 2016, 72 UAM returned voluntarily (DT&V, personal communication, 13 October 2016). After the expiration of the departure deadline of 28 days, and in cases of unwillingness to cooperate on voluntary return, the DT&V may decide to force the child to return to the country of origin. In that case, they may be placed in a detention facility to prevent them from leaving for parts unknown. Since October 2014, a more child-friendly closed reception facility has opened, which, at first sight, should look less like a prison than the previous detention facilities (Parliamentary paper of the Lower House, 2014-2015, 19 637, no. 1896). In terms of its administrative practice, however, it appears that the DT&V rarely initiates the forced return of children (Nidos, personal communication, 24 August 2016). From 1 June 2013 to 1 August 2016, a total of 19 UAM were deported by force (DT&V, personal communication, 13 October 2016).

Return to the country of origin for UAM can only be realized if suitable accommodation and care is available. According to the national and EU-wide policy regulations, the suitability of accommodation and care is available when a family member to the fourth degree can be traced. If family members cannot be traced, suitable accommodation and care is also considered to be available if there is a children’s home in the country of origin that complies with the local standards of shelter, nutrition, hygiene, education, and medical care.

UAM who were below the age of fifteen upon arrival, whose identity was undoubted, and who fully cooperated with the authorities to organize their return to the home country, but who were not able to realize this after a maximum period of three years, may be eligible for a so-called ‘no fault of your own’ permit. To date, this permit has not been granted (Appendix to the Proceedings of the Lower House of Parliament 2015-2015, no. 3430). The conditions to be eligible for this permit are hard to meet, as everything that can reasonably be done to enable the return has to be initiated by the respective child – supported by his/her guardian and lawyer – and proven to be unsuccessful to the IND. Until recently, in practice, those return activities were not undertaken and therefore there are no children who can state that they are still in the Netherlands beyond their will and intentions. Consequently, applications for the 'no fault of your own' permit were considered to be doomed to fail (Nidos, personal communication, 20 September and 5 October 2016).

3.4 Best Interests of the Child principle in Dutch Migration Law

The IND primarily executes the Dutch migration law framework, which is deemed to be in compliance with the existing binding rules of European and international law. However, Article 3 of the CRC, which stresses that the best interests of the child are a primary consideration in every decision that affects children, is not implemented in Dutch migration law as it should be (Beltman/Kalverboer/Zijlstra/Van Os/Zevulun 2016). The Council of State ruled on the one hand that this provision must be expressed in decisions concerning children but on the other hand did not verify whether the IND assessed and weighed the best interests of the child in their decision-making process (Council of State, 7 February 2012). The conclusion is that the principle of the best interests of the child is only formally included in decisions (Beltman/Zijlstra 2013).

4 Unaccompanied minors in care arrangements

In the Netherlands, there are various care arrangements for UAM. Most UAM stay with foster families, some stay in small care facilities or in large reception centers. Sometimes children are sheltered at asylum-seeking centers for adults. This happens for various reasons (staying with an acquaintance, waiting for family reunification, or shortage of placements due to the high influx). A small fraction of all UAM stays in protected shelters for victims of human trafficking (De Ruijter de Wildt et al. 2015; Nidos 2016). The distribution of UAM in the different care facilities is presented in table 4.

Table 4 Distribution of unaccompanied minors in care facilities on 16 August 2016 (Interview Nidos, 2016)

|

Care arrangement |

Number unaccompanied minors |

|

Family care |

1809 (33%) |

|

Small care facilities |

1696 (31%) |

|

Small living group |

548 |

|

Small living unit |

1051 |

|

Small living facilities |

97 |

|

Large reception centres |

1292 (24%) |

|

Process and Reception Location |

386 |

|

Campus |

106 |

|

Asylum seeking centre[3] |

800 |

|

Protected shelter |

45 (1%) |

|

Other |

581 (11%) |

|

Total |

5423 (100%) |

The reception of UAM is related to the phases and outcomes of the residence procedure. When arriving in the Netherlands, UAM under fifteen years and extra vulnerable children are placed in foster families. Children who are fifteen through eighteen years old stay in a registration and application center for a couple of days. After finishing the process of registration, they are placed temporarily in a large-scale care facility, the POL. The children are placed in long-term facilities (foster families, small care facilities, or large reception centers) after the decision of the IND regarding their asylum application or the decision to handle the request in the extended procedure [VA].

Since 1 January 2016, a new reception model came into force. One change in the new model is that children above fifteen years old are housed separately, depending on their migration status. Nidos is responsible for the housing of children with a residence permit (small care facilities) and for all children placed in foster families. Nidos is also responsible for the recruitment, screening, preparation, and supervision of the foster families. The housing of children without a residence permit or pending the extended asylum procedure is the responsibility of the Central Agency for the Reception of Asylum Seekers (COA). Children without a residence permit live in the large reception facilities or small care facilities. The small care facilities are sometimes outsourced by COA and Nidos to a youth care organization (COA, 2016; Nidos, 2016; VNG, 2016). Another change in the new reception model is that the large care reception facility (campus) is no longer part of the reception model. Because this change is deferred until January 2017 (Annual Report Children's Rights 2016; COA 2016), we will include this care facility in the description of the care arrangements. In this section, the care arrangements and the child's experiences of the quality of these facilities will be discussed.

4.1 Care arrangements

This section describes the different care arrangements which are available for UAM in Netherlands, depending on their age, the phase and outcome of their asylum procedure, their needs and vulnerability.

Foster families

About one third of the UAM staying in the Netherlands are placed in foster families with the same cultural background to provide suitable reception and safety for the children. Some children have family members or other relatives in the Netherlands who can take care of them. If they have not, the child is placed with a foster family of no relation (De Ruijter de Wildt et al. 2015). If possible, siblings are placed together. There is no shortage of foster families for the reception of UAM. Since the high influx of refugees (mainly coming from Eritrea and Syria), the recruitment of foster families with the same background as the Eritrean and Syrian children has been successful (De Ruijter de Wildt et al. 2015; Inspectorate Youth Care 2014; Nidos 2016).

In 2015 the Nidos foundation developed a new care arrangement for UAM in foster families. A group of four children are placed together in one family. Children and care givers share their cultural background and language. This type of care arrangement replicates, to a certain degree, what children were used to when they lived in an extended family in their country of origin (De Ruijter de Wildt et al. 2015).

Process Reception Location (POL)

The POL is a large reception center with a 24-hour supervision. Every UAM is linked to a mentor. During their stay, the UAM have contact with various authorities, such as the IND and their lawyer. During their stay at the POL (on average three months), it will be determined which care facility meets the needs of the UAM considering their age, level of autonomy, and vulnerability. The decision about the next reception facility also depends on the outcomes of the asylum procedure (Nidos 2016).

Small care facilities

Fourteen- through sixteen-year-olds, who are more self-reliant, are placed in small care facilities. There are three types of small care facilities. The first is a small living group which accommodates twelve to twenty children (with a residence permit) and provides 24-hour supervision. The small living group is situated in the neighborhood of a village or city. The supervision is aimed at increasing the self-reliance of UAM so they can move on to the small living unit (type two). In a small living unit children with a residence permit, live together with three or four young persons. Supervision is available for a few hours a day (28.5 hours a week) and young persons can stay there until they are eighteen. The supervisors prepare them for independent living. A small living unit is situated in the neighborhood of a village or city (Child Rights Monitor 2015; Nidos 2016).

Children without a residence permit, are staying in small living facilities (type three) which houses a maximum of twenty children. These small living facilities are situated at asylum-seeking centers or in the neighborhood. There is a 24-hours supervision, which focuses on the children’s preparation for their future. That is that the supervisor will prepare with the respective child for his/her integration in the Netherlands or his/her return to the country of origin (COA 2016).

Campus

For a long time, children who are sixteen through eighteen years old were placed in large reception centers (campuses) on their arrival in the Netherlands. Most of these campuses have been closed, but not all. The campuses are situated at the regular asylum seekers’ centers and each campus accommodates an average of 100 UAM. The assumption is that those adolescents have a high level of self-reliance and autonomy, and that they can take care of themselves. At the campus, there is little supervision to increase self-reliance. In order to support children to become independent, activities such as cooking classes are organized. UAM share their bedrooms, their living room and the facility’s kitchen with each other. The children are responsible for cleaning their facilities (Nidos 2016).

Protected shelter for victims of human trafficking

Since 2008, UAM who possibly are victims of human trafficking are placed separately in a protected, small care facility because of an assumed risk of disappearances and abductions. By sheltering these children separately, the aim is to detach them from the influence of their human trafficker, to provide safety, and to increase the UAM’s awareness of their own autonomy. Most of the times, children stay for nine months in the protected shelter. From the protected shelter, children can be placed in regular care facilities for UAM (National rapporteur on human trafficking and sexual violence against children 2015; Child rights monitor 2015).

4.2 How do unaccompanied minors experience these care arrangements?

Several Dutch studies show that children who stay in more restrictive and large reception centers have higher rates of mental health problems compared to children staying in other care arrangements (Bean et al. 2007; Kalverboer et al. 2016; Reijneveld et al. 2005). UAM living in foster families are most satisfied about their living environment, and UAM housed in large receptions centers are least satisfied (Inspectorate Youth Care 2012a; 2012b; Kalverboer et al. 2016).

UAM staying in foster families mostly have affectional bonds with their caregivers, they feel more integrated in Dutch society, visit regular Dutch schools, and have more Dutch friends compared to the UAM in other care facilities. UAM housed in campuses have to take care of themselves, do not have sufficient resources to buy the food they prefer, and lack the love and support of their parents. Supervisors are insufficiently available (Kalverboer, et al. 2016). Children experience the atmosphere in campuses as negative and indicate the misuse of alcohol and drugs (Annual Report Children's Rights 2016). Campuses are sparingly furnished, small, grubby, and noisy (Inspectorate Youth Care 2012a). Children often feel lonely and sad (Kalverboer et al. 2016). Sources of support which help them to forget their problems for a moment include: education, friends, guardians, teachers, sport (football) coaches, and leisure time activities like sports, music, and playing computer games. Children want to live a normal life, prefer to attend Dutch schools, and to realize their future plans. It seems that the reception and living in foster families meet those wishes best (Kalverboer et al. 2016). The negative experiences of children at campuses have led to a policy change to close the campuses (Annual Report Children's Rights 2016).

Alarming is that in 2015, 160 children disappeared from care facilities with an unknown destination (Annual Report Children's Rights 2016). There is little inside information of the reasons of these disappearances and where children ended up. Some children disappeared just before their eighteenth birthday, and some children who had stayed in a protected shelter may probably be under the influence of their human trafficker again (Annual Report Children's Rights 2016; Inspectorate Youth Care & Inspectorate Security and Justice 2016; Kromhout et al. 2010; National rapporteur on human trafficking and sexual violence against children 2015).

4.3 Unaccompanied minors turning eighteen

For UAM, turning eighteen means that they have to leave the reception centers for children. If they are still waiting for the outcome in the asylum procedure, they are transferred to facilities for adults and receive a minimum of social benefits. If the application is rejected and all legal remedies are exhausted, UAM have to leave the care facility and must take care of themselves. From then on, they are seen as irregular migrants who have to arrange their ‘voluntarily’ return to the country of origin or otherwise they can be forced to leave the Netherlands.

There are several initiatives in the Netherlands to support unaccompanied youth after their eighteenth birthday. The support focuses on primary living conditions, legal procedures, and education, on creating a positive future perspective, integration in the Netherlands and/or the young person’s return to his/her country of origin. Some unaccompanied young adults leave for an unknown destination in other countries or live irregularly in the Netherlands (Staring/Aarts 2010).

UAM with a residence permit who turn eighteen are entitled to the same facilities as Dutch people; they can work, rent their own housing, and if they want to study they can make a request for a student grant or other social benefits (Child Rights Monitor 2015; Nidos 2016).

UAM without a residence permit in the Netherlands experience a difficult transition as soon as they have turned eighteen, going along with a lot of fear and uncertainty (Kalverboer et al. 2016). They feel alone in the world and their eighteenth birthday is a sad day in their lives (Goeman/Van Os 2013). Staring and Aarts (2010) studied the circumstances of formerly UAM, who had to return to their country of origin but stayed in the Netherlands irregularly. They concluded that it seems difficult for these formerly UAM to find housing and some of them keep wandering around. They obviously have very limited possibilities to get an education, and their access to medical health services is poor. They are financially dependent on charity organizations or friends, while their social networks are small and the fear of getting caught by the police is huge (Staring/Aarts 2010).

5 Conclusion and discussion

In recent years, those UAM arriving in the Netherlands mainly came from Syria, Eritrea, and Afghanistan: war torn countries. These children have experienced a high number of stressful life events such as separation from and loss of close family members and exposure to violence before and during their migration (Jensen et al. 2015). Upon arrival, refugee children show a disproportionally high level of psychological problems, like anxiety disorders, trauma-related stress, and depression (Van Os et al. 2016). This knowledge about their vulnerability should be taken into consideration in decisions made in the asylum procedure and in decisions on the most appropriate care facilities.

Unaccompanied refugee children in the Netherlands develop best by placement in foster families compared to children in reception centers (Kalverboer et al. 2016). For Dutch children who live in out-of-home-care these differences are also known (Leloux-Opmeer et al. 2016). The choice for a family environment above residential care is encouraged by article 20 of the CRC and the UN guidelines for Alternative Care of Children (United Nations, 2009, para. 21). The right of the child to live in a family-like environment is based on knowledge in behavioral and social sciences, which show that every child needs caregivers who provide the child with an affective atmosphere in which bonds of attachment can be established and continued (Zijlstra 2012, pp. 25-26). For that reason, it is worrying that children – from the age of fifteen – who do not have a residence permit have limited access to foster family care. This form of discrimination on the grounds of residence status is contrary to the non-discrimination principle laid down in article 2 of the CRC.

5.1 Main challenges

In the asylum procedure, the migration authorities as well as the judges do not fulfill the obligation derived from article 3 of the CRC to assess and determine the child’s best interests (Beltman et al. 2016). This may lead to severe violations of children’s rights in the Netherlands, as some children will not receive the protection they need.

Although it has been indicated in this article that living in foster families offers the best rearing environment for UAM, a majority still lives in groups or even large reception centers. It is of great concern that so many children lack the stability and love of a family-like environment. Moreover, due to the frequent removals of asylum seekers in the Netherlands, those children also have to adjust again and again to new social workers at the reception centers. While children in foster families – beside the bonds with the caregivers – do also profit from stability at school and relationships with peers, the ones at the reception centers have to build a new life with each removal. In general, a high number of relocations of asylum-seeking children is a risk factor for their mental health (Nielsen et al. 2008). Despite the fact that policy provides that children of fifteen years or younger and the most vulnerable children are sheltered in foster families, the current reception model of UAM is still based on stages and outcomes of the asylum procedure. For the Netherlands, it is a challenge to develop a reception model fully built on the needs of the UAM and children's rights as a guiding principle.

Turning eighteen means for many UAM to face the threat of deportation to their country of origin. Despite the intentions of Nidos and DT&V to cooperate on return, for many young persons for whom voluntary return cannot be arranged and who seem not to be forcibly expelled by the DT&V, their transition to adulthood means that they will be forcibly expelled to their country of origin without guarantees concerning suitable accommodation and care. In contrast, in Dutch Youth Care supplying Dutch Citizens with services, young people are taken care of until the age of twenty-three (Youth Act, Art. 1.1). This provides them with a more gradual transition to adulthood.

The social and political climate has become worse for foreigners in general and arriving asylum seekers in particular. The United Nations stated in a report about the Netherlands that there is: “… [concern] about the situation of asylum-seekers in the State party, including the increase in hostility towards refugees and asylum-seekers among the population and opposition to the opening of new reception centres” (United Nations 2015, para. 33). Reaching safety in a hostile atmosphere is an added risk factor for refugee children’s mental health (Montgomery, 2008). Moreover, the feeling of belonging to the new society by experiencing social support is an important factor that could enhance the resilience of UAM (Sleijpen/Boeije/Kleber/Mooren 2016). For adolescents, the negative social and political climate against refugees might also harm them in terms of their (mental) health development, since social comparison and the perception of others are of growing importance during this period of their lives (Zijlstra 2012, pp. 42-43).

5.2 Recommendations

With regard to the asylum procedure, the role and duties of guardians should be taken more seriously by the decision makers in migration procedures and recognized in asylum law. The guardians have the legal obligation to guarantee the well-being of UAM. Their views on the best interests should be leading the migration decisions (Arnold/Goeman/Fournier 2014).

Besides the need for (better) best interests of the child assessments in the asylum procedures, the asylum legislation needs improvement. Pobjoy (2015) therefore suggests to provide the possibility to grant children protection on the grounds of their best interests based on the CRC, although they do not fulfill the criteria for a refugee status according to the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees.

Regarding the reception, Bandura (1971) advises to place all children in foster families, except when a placement in other forms of out-of-home-care would be in the best interests of the child. Large reception facilities should be closed. This might prevent the worsening of mental health problems of UAM. Sheltering UAM with mental health problems together in one place creates the risk that children will copy destructive behavior exhibited by other children (Bandura 1971).

If an UAM has to return to the country of origin, a multidisciplinary team should be involved to compose, realize, and monitor a return plan that protects the safety, development, and well-being of the child (Goeman/Walst 2016).

Social workers in the care arrangements and other professionals should identify concerns regarding serious mental health complaints and ensure access to health care (Bean 2006). When UAM arriving in a care facility it is necessary to spent time with them to build up trust and to get information about their mental health, the quality of the rearing environment in their home country, their experiences during their flight, and their wishes about the future. Therefore, the use of diagnostic assessment tools is recommended, The Best Interests of the Child Methodology, which is in line with the guidelines of the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child (Kalverboer 2014, p. 15), could be useful tool to meet these elements (Van Os/Zijlstra/Knorth/Post/Kalverboer 2017). Besides that, it is important that social workers support UAM in having a ‘normal’, regular, and stable life. Facilitating contact with peers and other resources in the social network and facilitating adequate education will enlarge the resilience of the children and assist them to regain control over their lives (Sleijpen et al. 2016).

5.3 Further research

Further research is needed to gain in-depth insight into the factors that contribute to a successful stay of the UAM in a foster family. In the Netherlands, Nidos tries to find as many 'cultural foster families' as possible because children seem to profit from contacts with people from same ethnic background. On the other hand, UAM might more easily find their place in Dutch society with the support of a family of Dutch origin. So, what are the pros and cons of cultural matching between the children and the families?

Research on UAM who have returned to their home countries hardly exists (Zevulun et al. 2015, 2016). UAM who have returned to their home country are not monitored in the Netherlands and the Dutch government does not consider this as their responsibility. Besides the difficult traceability of returned UAM, such a research is intensive, expansive and a real challenge but absolutely necessary to gain insight into the risk and protective factors for a sustainable return of UAM to the country of origin.

References

Annual Report Children’s Rights (2016). Kinderrechten in Nederland [Children's rights in The Netherlands]. Leiden, the Netherlands: Unicef, Defence for Children.

Arnold, S., Goeman, M., & Fournier, K. (2014). The Role of the Guardian in Determining the Best Interest of the Separated Child Seeking Asylum in Europe: A Comparative Analysis of Systems of Guardianship in Belgium, Ireland and the Netherlands. European Journal of Migration and Law, 16(4), 467 – 504.

Bandura, A. (1971). Social learning theory. New York: General Learning Press.

Bean, T., Eurelings-Bontekoe, E., Mooijaart, A., & Spinhoven, P. (2006). Factors associated with mental health service need and utilization among unaccompanied refugee adolescents. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 33(3), 342-355.

Bean, T. M., Eurelings-Bontekoe, E., & Spinhoven, P. (2007a). Course and predictors of mental health of unaccompanied refugee minors in the Netherlands: One year follow-up. Social Science and Medicine, 64, 1204-1215.

Bean, T., Derluyn, I., Eurelings-Bontekoe, E., Broekaert, E., & Spinhoven, P. (2007b). Comparing psychological distress, traumatic stress reactions and experiences of unaccompanied refugee minors with experiences of adolescents accompanied by parents. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 195(4), 288-297.

Beltman D., Kalverboer, M. E., Zijlstra, A. E., Van Os, E. C. C., & Zevulun, D. (2016). The Legal Effect of Best-Interests-of-the-Child Reports in Judicial Migration Proceedings: A Qualitative Analysis of Five Cases. In T. Liefaard, & J. Sloth-Nielsen (Eds.), The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child: Taking Stock after 25 Years and Looking Ahead. (pp. 655-680). Leiden, the Netherlands: Brill | Nijhoff

Beltman, D., & Zijlstra, A. E. (2013). De doorwerking van ‘het belang van het kind’ ex artikel 3 VRK in het migratierecht: vanuit een bottom-up benadering op weg naar een top-down toepassing [The direct effect of Article 3 CRC concerning the ‘best interests of the child’ in migration law: from a bottom-up approach towards a top-down implementation]. Journaal Vreemdelingenrecht, 12(4), 286-308.

Buisman, M., Soest, F.M., Göbbels, M.J.M., Swarts, H.W., Buis, C., & Roorda, S.C. (2016). Informatiedocument onderwijs aan asielzoekerskinderen [Information Document Education for asylum seeking children]. The Hague: Ministerie van Onderwijs, Cultuur en Wetenschap.

Child Rights Monitor [Kinderrechtenmonitor] (2015). The Hague: Kinderombudsman.

COA (2016). Locations for young people. Retrieved October 2016 from: https://www.coa.nl/en/about-coa/coa-locations/locations-for-young-people.

De Ruijter de Wildt, L., Melin, E., Ishola, P., Dolby, Murk, J., & Van der Pol, P. (2015). Reception and living in families. Overview of family-based reception for unaccompanied minors in the EU Member States. Utrecht, the Netherlands: Nidos.

Eurostat (2016a). Press release: Asylum applicants considered to be unaccompanied minors. Retrieved November 2016 from: http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/2995521/7244677/3-02052016-AP-EN.pdf/.

Eurostat (2016b). Asylum applicants considered to be unaccompanied minors by citizenship, age and sex. Annual data (rounded). Retrieved November 2016 from: http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/data/database?node_code=migr_asyunaa.

Goeman, M., & Van Os, C. (2013). Implementing the Core Standards for Guardians of Separated Children. Country assessment: The Netherlands. Leiden: ECPAT The Netherlands; Defence for Children.

Goeman, M., Van Os, C., Bellander, E., Fournier, K., Gallizia, G., Arnold, S., Gittrich, T., Neufeld, & Uzelac, M. (2011). Core Standards for guardians of separated children in Europe: Goals for guardians and authorities. Leiden: ECPAT The Netherlands; Defence for Children.

Goeman, M., & Walst, J. (2016). Beschadigen of bescherming. Stand van zaken drie jaar na de herijking van het amv-beleid. [Harm or protect? State of the new policy for unaccompanied minors, three years after introduction. Asiel- en Migrantenrecht, 2016(8), 367-373.

Hilverdink, P., Daamen, W., &Vink, C. (2015). Children and youth support and care in the Netherlands. Retrieved November 2016 from Netherlands Youth Institute: http://www.youthpolicy.nl/en/Download-NJi/Publicatie-NJi/Children-and-youth-support-and-care-in-The-Netherlands.pdf.

Hopkins, P., & Hill, M. (2010). The needs and strengths of unaccompanied asylum-seeking children and young people in Scotland. Child and Family Social Work, 15(4), 399-408.

IND (2015). Asylum Trends: Monthly report on asylum applications in The Netherlands and Europe Retrieved December 2015, from IND Business Information Centre : https://ind.nl/Documents/Asylum%20Trends%20December%202015.pdf.

Inspectorate Youth Care [Inspectie Jeugdzorg] (2012a). Grootschalige opvang van alleenstaande minderjarige vreemdelingen. Opvang van amv's op drie campussen [Large scale reception unaccompanied minor asylum seeking children three campuses]. Utrecht, the Netherlands: Inspectie Jeugdzorg, Ministerie van Volksgezondheid, Welzijn en Sport.

Inspectorate Youth Care [Inspectie Jeugdzorg] (2012b). Grootschalige opvang van alleenstaande minderjarige vreemdelingen. Opvang van amv's op de proces opvanglocaties [Large scale reception unaccompanied minor asylum seeking children on proces reception centres]. Utrecht, the Netherlands: Inspectie Jeugdzorg, Ministerie van Volksgezondheid, Welzijn en Sport.

Inspectorate Youth Care [Inspectie jeugdzorg] (2014). Opvang en woongezinnen van Nidos [Reception and living families of Nidos]. Utrecht, the Netherlands: Inspectie Jeugdzorg, Ministerie van Volksgezondheid, Welzijn en Sport.

Inspectorate Youth Care and Inspectorate Security and Justice] [Inspectie Jeugdzorg en Inspectie Veiligheid en Justitie] (2016). De kwaliteit van de beschermde opvang voor alleenstaande minderjarige vreemdelingen [The quality of the protected reception centre for unaccompanied minor asylum seekers]. Utrecht / The Hague, the Netherlands: Ministerie van Volksgezondheid Welzijn en Sport, Ministerie van Veiligheid en Justitie.

Inspectorate of Education [Inspectie van het Onderwijs] (2016). De kwaliteit van het onderwijs aan nieuwkomers, type 1 en 2, 2014/2015. Evaluatie van de kwaliteit van AZC-scholen (type 1), relatief zelfstandige nieuwkomersvoorzieningen en grotere nieuwkomersvoorzieningen (type 2) [The quality of education for newcomers (type 1 and type 2), 2014/2015. Evaluation of the quality of AZC schools (type 1) relatively independent facilities for newcomers and larger facilities for newcomers (type 2)]. Utrecht, the Netherlands: Inspectorate of Education.

Jakobsen, M., Demott, M. A. M., & Heir, T. (2014). Prevalence of psychiatric disorders among unaccompanied asylum-seeking adolescents in Norway. Clinical Practice and Epidemiology in Mental Health 10, 53-58.

Jensen, T. K., Fjermestad, K. W., Granly, L., & Wilhelmsen, N. H. (2015). Stressful life experiences and mental health problems among unaccompanied asylum-seeking children. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 20(1), 106-116.

Kalverboer, M. E. (2014). The Best Interests of the Child in Migration Law: Significance and Implications in Terms of Child Development and Child Rearing. Amsterdam: SWP Publishers.

Kalverboer, M., Zijlstra, E., Van Os, C., Zevulun, D., Ten Brummelaar, M., & Beltman, D. (2016). Unaccompanied minors in the Netherlands and the care facility in which they flourish best. Child and Family Social Work.

Kohli, R. S. (2006b). The comfort of strangers: Social work practice with unaccompanied asylum-seeking children and young people in the UK. Child and Family Social Work, 11(1), 1-10.

Kromhout, M.H.C., Liefaard, T., Galloway, A.M., Beenakkers, E.M.Th., Kamstra, B., & Aidala, R. (2010). Tussen beheersing en begeleiding. Een evaluatie van de pilot 'beschermde opvang risico-AMV's [Between control and guidance. An evaluation of the pilot 'protected reception for UAMs at risk]. The Hague: WODC.

Leloux-Opmeer, H., Kuiper, C., Swaab, H., Scholte, E. (2016). Characteristics of Children in Foster Care, Family-Style Group Care, and Residential Care: A Scoping Review. Journal of Child Family Studies, 25(8), 2357-2371.

LOWAN (2016). Onderwijstypen [school types]. Retrieved August 2016 from: http://www.lowan.nl/primair-onderwijs/onderwijs/onderwijsorganisatie-2/onderwijstypen/.

Montgomery, E. (2010). Trauma and resilience in young refugees: A 9-year follow-up study. Development and Psychopathology, 22(2), 477-489. doi:10.1017/S0954579410000180.

National rapporteur on human trafficking and sexual violence against children [Nationaal Rapporteur Mensenhandel en Seksueel Geweld tegen Kinderen] (2015). Mensenhandel: Naar een kindgericht beschermingssysteem voor alleenstaande minderjarige vreemdelingen [Human Trafficking: Towards a child-centered protection for unaccompanied minors]. The Hague: Nationaal Rapporteur.

National rapporteur on human trafficking and sexual violence against children [Nationaal Rapporteur Mensenhandel en Seksueel Geweld tegen Kinderen] (2016). Zicht op kwetsbaarheid. Een verkennend onderzoek naar de kwetsbaarheid van kinderen voor mensenhandel. [View on vulnerability. An exploratory study of the vulnerability of children to trafficking]. The Hague: Nationaal Rapporteur.

Nidos (2016). Jaarverslag 2016 [Annual report 2016]. Utrecht, the Netherlands: Stichting Nidos.

Nielsen, S. S., Norredam, M., Christiansen, K. L., Obel, C., Hilden, J., & Krasnik, A. (2008). Mental health among children seeking asylum in Denmark--the effect of length of stay and number of relocations: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health, 8, 293-301.

Pobjoy, J. M. (2015). ‘The best interests of the child principle as an independent source of international protection’, International and Comparative Law Quarterly, 64(2), 327-363.

Reijneveld, S. A., De Boer, J. B., Bean, T., & Korfker, D., (2005). Unaccompanied adolescents seeking Asylum. Poorer mental health under a restrictive reception. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 193(11), 759-761.

Sleijpen, M., Boeije, H. R., Kleber, R. J., & Mooren, T. (2016). Between power and powerlessness: a meta-ethnography of sources of resilience in young refugees. Ethnicity & Health, 21(2), 158-180.

Spinder, S. & Van Hout, A. (2008). Jong en Onderweg. Nidos-methodiek voor begeleiding van ama’s [Young and on the road. Nidos methodology for the support of unaccompanied minors]. Utrecht, the Netherlands: Stichting Nidos.

Starink, R. & Aarts, J. (2010). Jong en illegaal in Nederland [Young and illegal in the Netherlands]. The Hague / Rotterdam: WODC / Erasmus University.

United Nations (2009). Guidelines for the alternative care of children [Resolution General Assembly]. Retrieved September 2016, from: http://www.refworld.org/docid/4c3acd162.html.

United Nations (2015). Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination. Concluding observations on the nineteenth to twenty-first periodic reports of the Netherlands. UN doc: CERD/C/NLD/CO/19-21. Retrieved November 2016 from UN coc:CERD/C/NLD/CO: http://tbinternet.ohchr.org/Treaties/CERD/Shared%20Documents/NLD/CERD_C_NLD_CO_19-21_21519_E.pdf.

Van Os, E. C. C., Kalverboer, M. E., Zijlstra, A. E., Post, W. J., & Knorth, E. J. (2016). Knowledge of the unknown child: A systematic review on the elements of the Best Interests of the Child Assessment for recently arrived refugee children. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 19(3), 185-203.

Van Os, C., Zijlstra, E., Knorth, E. J., Post, W. & Kalverboer, M. (2017). Methodology for the assessment of the best interests of the child for recently arrived unaccompanied refugee minors. In M. Sedmak, B. Sauer, & B. Gornik, B. (Eds.), Unaccompanied children in European migration and asylum practices: in whose best interests? (pp. 59-85). Abingdon, UK / New York, US: Routledge, Taylor and Francis group (forthcoming).

Vervliet, M., Meyer Demott, M. A., Jakobsen, M., Broekaert, E., Heir, T., & Derluyn, I. (2014). The mental health of unaccompanied refugee minors on arrival in the host country. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 55(1), 33-37.

VNG (Vereniging Nederlandse Gemeenten, Platform opnieuw thuis) [Dutch Municipalities Association, Platform Back Home] (2016). Factsheet Alleenstaande Minderjarige Vreemdelingen [Factsheet unaccompanied minors]. Retrieved August 2016 from: https://vng.nl/files/vng/20160531-factsheet-amv.pdf.

Zevulun, D., Kalverboer, M. E., Zijlstra, A. E., Post, W. J., & Knorth, E. J. (2015). Returned migrant children in Kosovo and Albania: Assessing the quality of childrearing from a non-Western perspective. Cross-Cultural Research, 49(5), 489-521.

Zevulun, D., Kalverboer, M., Zijlstra, E., Post, W., & Knorth, E. J. (2016). Returned asylum-seeking children: How are children who stayed in European host countries faring after return to their country of origin? In J. F. del Valle, A. Bravo, & M. López (Eds.), Shaping the future: Connecting knowledge and evidence to child welfare practice (pp. 292-293). Oviedo, Spain: Asociación NIERU Publishers.

Parliamentarian Documents

Appendix to the Proceedings of the Lower House of Parliament, 2015-2015, no. 3430.

Government [Rijksoverheid] (2016). Alleenstaande minderjarige vreemdelingen [Unaccompanied Minor Aliens]. Retrieved April 2017 from: https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/onderwerpen/asielbeleid/inhoud/alleenstaande-minderjarige-vreemdelingen-amv.

Minister and State Secretary of Education, Culture and Science [Minister en Staatssecretaris van Onderwijs, Cultuur en Wetenschap]. [] (2015). Onderwijs aan asielzoekers. Brief van de Minister en Staatssecretaris van Onderwijs, Cultuur en Wetenschap aan de Voorzitter van de Tweede Kamer der Staten-Generaal [Education for asylum seekers. Letter of the Minister and State Secretary of Education, Culture and Science to the President of the House of Representatives of the Dutch Parliament]. Kamerstuk 2015/10, 34334, nr. 1.

Parliamentary paper of the Lower House, 2011-2012, 27062, no. 75.

Parliamentary paper of the Lower House, 2014-2015, 19 637, no. 1896

Case Law

Council of State 7 February 2012, ECLI:NL:RVS:2012:BV3716. Retrieved April 2017 from: http://www.raadvanstate.nl/.

Council of State 23 January 2013, 201200110/1/V1. Retrieved April 2017 from: http://www.raadvanstate.nl/.

District court The Hague, location Amsterdam, 4 April 2014, ECLI:NL:RBDHA:2014:10106. Retrieved April 2017 from: https://uitspraken.rechtspraak.nl/

Law

Aliens Act [Vreemdelingenwet] (2000). Retrieved April 2017 from: http://wetten.overheid.nl/BWBR0011823/2017-01-01

Aliens Circular [Vreemdelingencirculaire] (2000). Retrieved April 2017 from: http://wetten.overheid.nl/BWBR0012287/2017-04-01; http://wetten.overheid.nl/BWBR0012289/2017-04-01; http://wetten.overheid.nl/BWBR0012288/2017-03-29

Aliens Decree [Vreemdelingenbesluit] (2000). Retrieved April 2017 from: http://wetten.overheid.nl/BWBR0011825/2017-01-01

Aliens Regulation [Vreemdelingenvoorschrift] (2000). Retrieved April 2017 from: http://wetten.overheid.nl/BWBR0012002/2017-04-05

Civil Code (CC) [Burgerlijk Wetboek]. Retrieved September 2017 from: http://www.dutchcivillaw.com/civilcodebook01.htm

Youth Act [Jeugdwet] (2014). Retrieved April 2017 from: http://wetten.overheid.nl/jci1.3:c:BWBR0034925&z=2016-08-01&g=2016-08-01

Youth Act Decree [Besluit Jeugdwet] (2014). Retrieved April 2017 from: http://wetten.overheid.nl/jci1.3:c:BWBR0035779&z=2016-05-27&g=2016-05-27

Author’s Addresses

A.E. Elianne

Zijlstra, Phd

Study Centre on

Children, Migration and Law, Faculty of Behavioural and Social Sciences,

University of Groningen

http://www.rug.nl/research/study-centre-for-children-migration-and-law

Grote Rozenstraat

38 NL

9712 TJ Groningen

The Netherlands

Tel. +31(0)50-3636541

J.A. Rip, MSc

Study Centre on

Children, Migration and Law, Faculty of Behavioural and Social Sciences,

University of Groningen

http://www.rug.nl/research/study-centre-for-children-migration-and-law

Grote Rozenstraat

38 NL

9712 TJ Groningen

The Netherlands

j.a.rip@rug.nl

D. Beltman, LLM

Study Centre on

Children, Migration and Law, Faculty of Behavioural and Social Sciences,

University of Groningen

http://www.rug.nl/research/study-centre-for-children-migration-and-law

Grote Rozenstraat

38 NL

9712 TJ Groningen

The Netherlands

d.beltman@rug.nl

E.C.C. van Os, MSc, LLM

Study Centre on

Children, Migration and Law, Faculty of Behavioural and Social Sciences,

University of Groningen

http://www.rug.nl/research/study-centre-for-children-migration-and-law

Grote Rozenstraat

38 NL

9712 TJ Groningen

The Netherlands

e.c.c.van.os@rug.nl

Prof. E.J. Knorth, PhD

Special Needs

Education and Youth Care, Faculty of Behavioural and Social Sciences,

University of Groningen

Grote Rozenstraat 38 NL

9712 TJ Groningen

The Netherlands

e.j.knorth@rug.nl

Prof. M.E. Kalverboer, PhD, LLM

Study Centre on

Children, Migration and Law, Faculty of Behavioural and Social Sciences,

University of Groningen

http://www.rug.nl/research/study-centre-for-children-migration-and-law

Grote Rozenstraat

38 NL

9712 TJ Groningen

The Netherlands

m.e.kalverboer@rug.nl