Unaccompanied Minors in Germany. A success story with setbacks?

Maren Zeller, Trier University

Philipp Sandermann, Leuphana University of Lüneburg

1 Introduction

During recent years, the number of unaccompanied minors (UAM) seeking protection in Germany has started to rise significantly. While other European countries such as Greece (Fili & Xythali, 2017) can be described as transit zones for UAM who tend to travel on, Germany falls into the category of being a final destination.[1] There is no explicit research on the reasons why UAM choose Germany as their final destination, but data regarding refugees in general suggest that this is partly because of the asylum system, which is known as fair, and partly because of the good economic situation, which seems to promise good housing and job opportunities for everyone (Müller, 2014). Furthermore, the presence of migrants from the same countries of origin is known to be a pull factor (Parusel, 2017).

In line with EU Directive 2011/95, the German term Unbegleitete minderjährige Flüchtlinge [unaccompanied refugee minors] characterizes an underage person (child or youth) who enters Germany as a third country national, who travels without a parent or a person holding parental rights (e.g. a legal guardian) and who defines himself/herself as a refugee (Gravelmann, 2016). Just lately (in 2015) the public authorities started to use the German term Unbegleitete minderjährige Ausländer [unaccompanied foreign minors]. This is intended to underline the fact that not everyone who describes him/herself as a refugee turns out to be a refugee according to the Geneva Convention on Refugees and the corresponding German legal framework. Public interest groups such as the Bundesfachverband unbegleitete minderjährige Flüchtlinge [Federal Association for Unaccompanied Minor Refugees] criticised this new policy very harshly and made the case for maintaining the term Unbegleitete minderjährige Flüchtlinge (BumF, 2015) because the young people were nonetheless likely to have experienced existential threat in their country of origin and during their flight. Nowadays (in 2017) most professional associations and also academia stick to the “old” term, while the public authorities tend to use the “new” term.

For many years UAM were a marginal phenomenon – in terms of numbers, but also in terms of public awareness. Furthermore, providing services for UAM was a confusing field of action since “child and youth care legislation and practice on the one hand and immigration and asylum laws on the other hand were contradictory with regard to UAM” (Parusel, 2017, p. 1). Interestingly, despite this contradiction, the legal situation of UAM seemed to improve steadily between 2005 and 2015 due to some major amendments to the Child and Youth Care Act that were guided by the idea of better incorporating the best interests of the child and adapting national legislation to international regulations protecting children and adolescents (e.g. the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child) (see Berthold 2014). Since the high influx of refugees during the so-called European refugee crisis, social services for UAM in Germany have expanded rapidly and faced some restrictions, though with several organizational and legislative changes in 2015. Even more restrictions have been proposed by some political parties during the last two years (e.g. BumF, 2017), but have not been successful so far.

Unlike other countries such as Canada or the UK, Germany holds no tradition of refugee studies as an autonomous academic field. Therefore, research on refugees in general and on UAM in particular is scarce.[2] Since the legislative changes in 2015 due to the high numbers of UAM arriving in Germany, the availability of statistical data has at least improved considerably. As many social workers/social pedagogues had to learn the ropes of working with and advising UAM, a larger body of practice-related literature emerged, with many titles focussing on how to deal with traumatized UAM in particular (see Kühn & Bialek, 2017; Zito & Martin, 2016; Quindeau & Rauwald, 2017). This development has, however, been criticized by authors who question the idea that specialized treatment for UAM might impede their inclusion into society (Graßhoff, 2017).

This article will discuss the situation of UAM in Germany by firstly analyzing the available statistical data, secondly giving an outline of the legal framework and its latest development and thirdly presenting a general view on clearance practices and care arrangements. Finally, challenges to establishing a broader body of research on this topic in Germany shall be discussed.

2 Statistical insights: What do we know about UAM in Germany?

Available data on the German situation broadly reflects recent international developments. In 2016, Germany was the world’s largest recipient of new individual asylum applications, and ranked second among European countries when it came to asylum applications by UAM. This was not a sudden development. Rather, the number of UAM had increased rapidly and constantly in the years leading up to 2016; they then started to decrease in 2017 (Eurostat, 2018).

2.1 Numbers

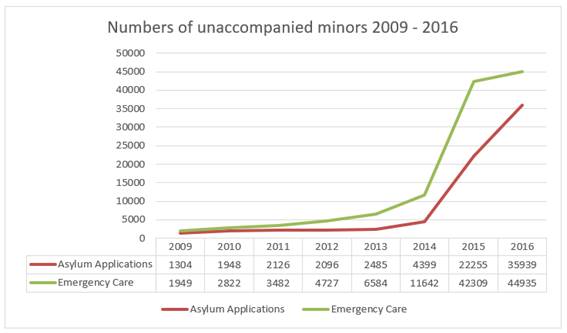

Two important numbers provide an initial impression of the situation of young people who are categorized as UAM in Germany. First, there is the total number of young persons that are taken into short-term custody or emergency care;[3] second, there is the total number of those young persons that apply for asylum as UAM.

Figure 1: Number of UM in emergency care and those applying for asylum

Sources: Statistisches Bundesamt, 2017, pp. 11,12; Deutscher Bundestag, 2017a, p. 21.

Both numbers have increased constantly during the last seven years. What might not be readily apparent from the data is the fact that the numbers of refugee minors taken into emergency care doubled between 2009 and 2011 and tripled between 2009 and 2013. This increase shows that there was not just a sudden influx of unaccompanied young people reaching Germany in 2015 and 2016, as discussed in public debates, but that there had been a longer development towards those exponentially high numbers of UAM who reached Germany between 2013 and 2016 (with almost 45,000 young people taken into emergency care in 2016 alone). The disproportionately high level of these numbers becomes clear when we look at the German child and youth care statistics marking out the total number of children taken into emergency care in Germany per year: in 2015, the proportion of UAM taken into emergency care was equivalent to 54.5% of all emergency care cases.

As shown in Figure 1, the numbers of young people taken into emergency care and those applying for asylum differ. There are continuously more young people taken into emergency care than there are young people applying for asylum. This gap directly reflects the fact that in Germany, asylum is mainly granted to people who can show they are victims of political persecution.[4] For UAM, this is often hard to prove, as it means verifying that they were individually persecuted in their home country. It is more likely, though, that UAM are recognized as refugees according to the Geneva Convention[5] or as people eligible for subsidiary protection[6]. But still there are cases where even some NGOs who advocate for the young people advise them not to apply for asylum because if an asylum application is rejected as manifestly unfounded, any chance is forfeited of ever getting a residence permit (e.g. for being “well-integrated” as set out in Section 25a, Subsection 1 of the Aufenthaltsgesetz [Residence Act])[7]. Another reason for not applying for asylum is that the personal interviews conducted at the Federal Office for Migration and Refugees (BAMF) can be traumatizing, especially for young people. Just lately, the BAMF has put in place special qualified interviewers for sensitive cases such as UAM. These specialized officers will take over the interviewing procedure from non-specialized officers and will decide on the asylum status (Gravelmann, 2016). During the interviews, particular emphasis is placed on ascertaining whether there are indications of child-specific reasons for flight, which include, for instance, genital mutilation, forced marriage, domestic violence, human trafficking or forced recruitment as a child soldier.

In Figure 1, the years 2015 and 2016 show a peak in UAM applying for asylum (22,255 to 35,939), and a less dramatic increase in those young people being taken into emergency care as UAM (42,309 to 44,935). In part, these figures may have resulted from the fact that many UAM who arrived in Germany in the second half of 2015 only submitted their asylum application in 2016 (Deutscher Bundestag, 2017a; Deutscher Bundestag, 2017b).

After the so-called clearance process (see next chapter), most UAM are sent to a residential group home[8], while a small number are sent to a foster family[9]. Until recently, there were no statistics available regarding the number of refugee minors placed in child and youth care. With amendments to the federal law concerning child and youth care in 2015 (see next chapter), data from November 2015 onwards became available.

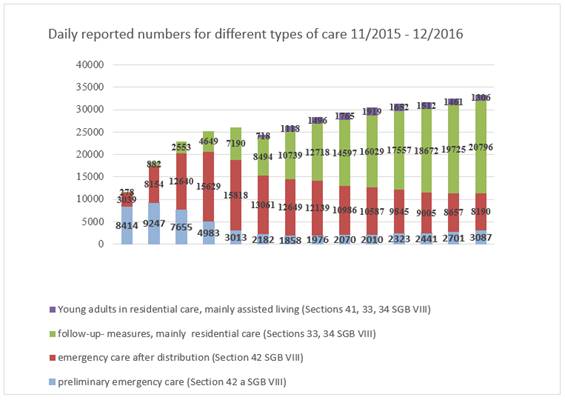

Figure 2: Increases and decreases according to different types of care

Source: Deutscher Bundestag, 2017a, p.25.

Overall, Figure 2 shows the daily reported numbers of UAM in emergency care before and after the distribution process (see Chapter 2) and the daily reported numbers of UAM in residential care before and after coming of age. During the last months of 2016, the numbers of UAM in emergency care decreased, while the numbers for those in residential care increased. This is due to fewer refugee minors entering Germany and therefore entering the child and youth care system. The numbers of young adults always seem to remain at quite a low level in comparison to the general numbers of UAM in care.[10]

2.2 Gender, age and countries of origin

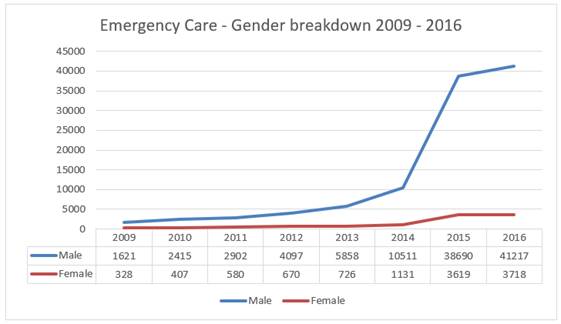

In Germany, as in other European countries, most of the young people who are taken into emergency care as UAM are male (in 2015, this correlated with 91.4% of all young people).

Figure 3: Number of male and female UAM taken into emergency care between 2009 and 2016.

Source: Statistisches Bundesamt, 2017, pp. 15,16.

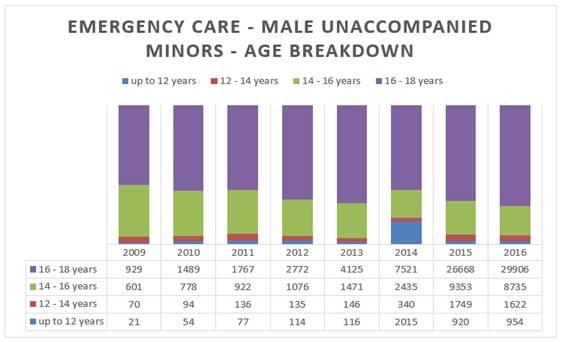

The majority (68% in 2015) of male UAM who are taken into emergency care are 16 to 18 years old. Almost a quarter of them are either 14 or 15 years old, while around 8% are younger than 14.

Figure 4: Age of unaccompanied males taken into emergency care between 2009 and 2016

Source: Statistisches Bundesamt, 2017, pp. 15, 16, and own calculation.

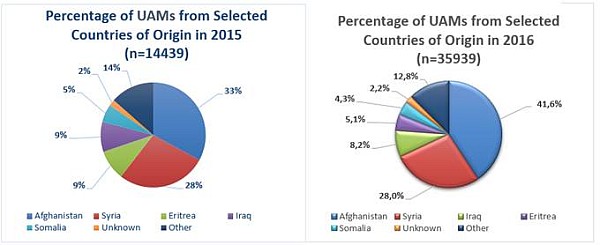

Regarding the countries of origin, there are no statistics on all the UAM who came to Germany, but only on those who applied for asylum. The BAMF collects this data. It shows that in 2015 and 2016, most young people who applied for asylum as UAM came from Afghanistan and Syria, followed by Iraq, Eritrea and Somalia.

Figure 5: Selected countries of origin of those UAM who applied for asylum in 2015 and 2016.

Source: Deutscher Bundestag, 2017b, p. 4; Deutscher Bundestag, 2017a, p. 44.

Although all of these numbers suggest that they form a relatively homogenous group in terms of age, gender and ethnicity, this is not consistent with reports by practitioners in Germany’s child and youth care. For example, an umbrella organization active in Baden-Württemberg, one of the 16 German Bundesländer[11], reports that they are in charge of 270 UAM coming from 32 different countries of origin, which they find quite a challenge (Kohlbach, 2015).

2.3 Refugee statuses

The question of which refugee status an UAM holds is quite complex, since the principles of the German Asylgesetz [Asylum Act], the German Aufenthaltsgesetz (AufenthaltG) and the Sozialgesetzbuch VIII: Kinder- und Jugendhilfe [Social Code, Book VIII: Child and Youth Care] overlap and interrelate, producing a complicated overall system. However, all minor refugees have been seen as children and therefore as a vulnerable group of people according to the UN CRC (see next chapter) ever since the aforementioned amendments to the Child and Youth Care Act in November 2015. Although UAM enter German ground illegally by definition (Section 14 Subs. 1 AufenthaltG), an obligation to leave the country is virtually impossible to enforce (Roßkopf, 2017)[12]. Usually, UAM hold a refugee status according to the Geneva Convention on Refugees, a subsidiary protection status according to European law or at least a deportation ban [Duldung] according to German law.

Among those UAM who apply for asylum, the granted protection rate is relatively high and has risen during recent years. In 2010, for instance, the protection rate averaged 36.3%, in 2013, it added up to 56.6% (Müller, 2014), and in 2016, it rose to 89% including the 20 most frequent countries of origin (Deutscher Bundestag, 2017b). However, there is a big variance in the protection rate when one distinguishes between countries of origin. In 2016, the highest protection rate was reached by stateless persons (100%), followed by UAM coming from Syria (98.4%), Iraq (93.7%), Eritrea (93.6%) and Sudan (without South Sudan) (90.0%). The protection rate includes different refugee statuses: very few of the young people (0.2% in 2016) are granted asylum according to Section 16a of the German Grundgesetz [Basic law]. Most of the young people are given refugee status based on the international protection agreements (Geneva Convention on Refugees, and European Convention on Human Rights) that are encompassed in German legislation.

56.6% of the young people were granted refugee protection according to the definitions in the Geneva Convention on Refugees, referred to in Section 3 Subs. 1 of the German Asylgesetz. Another 29% were granted subsidiary protection (Section 4 Subs. 1 Asylgesetz / EU Directive 2004/83/EC) in 2016. Another small group of young people (6% in 2016) received a deportation ban according to Section 60 Subs. 5/7 Aufenthaltsgesetz (Deutscher Bundestag, 2017a, p. 5). The average period taken to pass through an asylum process was 8.3 months in 2016 (Deutscher Bundestag, 2017a). Although this does not seem inordinately long, many UAM are turning 18 without knowing the result of their legal process (Espenhorst & Noske, 2017).

Young people who have received refugee status according to the Geneva Convention as UAM are likely to get a residence permit for three years, while young people who have subsidiary protection status are likely to get a residence permit for two years. If nothing changes during that time regarding their refugee status, and if they are what the law calls “well-integrated” they can apply for a settlement permit. This can be granted after either three or five years depending on the degree of integration (Section 26 Subs. 3 AufenthG). The definition of “well-integrated” includes two main indicators: a certain knowledge of the German language, and proof of economic self-sufficiency.

A deportation ban for UAM expires after a year. The Ausländerbehörde [immigration authorities] can extend the duration of the deportation ban by periods of another six months or one year as many times as they see fit, as long as there are reasons officially accepted by the German legislative authorities. This status means the young people it applies to are being kept in limbo. However, it can turn out well for them, if they gain a settlement permit after five years. To receive a settlement permit, the applicant has to prove economic self-sufficiency (Espenhorst & Noske, 2017).

UAM who do not apply for asylum usually apply directly for a residence document at the Ausländerbehörde and receive a deportation ban either until they are 18 or until their status has finally been decided on. There are different (but not many) ways to eventually receive a permanent residence permit:

1. If the young person starts a vocational training before the age of 21 (Ausbildungsduldung [suspension of deportation for the time the vocational training lasts], Section 60a AufenthaltG);

2. If the young person can prove that he or she is “well-integrated” (Section 25a Subs. 1 AufenthaltG). This new law from 2011 applies to all young people who have entered Germany before the age of 17, have been resident in Germany for four years without interruption and attended school for four years, graduated from school or successfully completed vocational training. Their application for the residence permit has to be completed before the age of 21. Refugee organizations and welfare associations welcomed the new provisions for UAM, since they provide better long-term opportunities at least to those who enter the country under 17 years of age (Federal Office for Migration and Refugees, 2016).

3. If the young person is adopted, or married to a German partner, or expecting a child, his or her status might change according to the status held by the other persons involved (Gravelmann, 2016).

3 The changing legal and political framework for UAM Reception in Germany

The legal and political situation of young people who came to Germany as refugee minors, and UAM in particular, has been very complex for many years due to two circumstances. Firstly, national legislation has existed alongside EU legislation and alongside the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, while their respective understanding of the “best interest of the child” (UNHCR/Unicef, 2014) did not precisely match. Secondly, up until November 2015, the German legal guidelines on who is legally authorized to act according to the Child and Youth Care Act (young people age 18) interfered with those of the Asylum Law (young people age 16). Below, we will give some insights into the key points of the legal situation of refugee minors in Germany and developments since the 1990s, when the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) became effective.

After World War II, Germany felt particularly committed to promoting very liberal legislation on refugees who were seeking asylum for reasons of political persecution. Therefore, the fundamental right to apply for asylum was enshrined in the constitutional Grundgesetz for the Federal Republic of West Germany in 1949, as well as in the constitution of the former GDR. This only changed at the beginning of the 1990s when Germany (now reunified) faced escalating numbers of refugees, mainly from Eastern Europe, due to the end of the Cold War and the beginning of the Yugoslav Wars. In 1993, the Bundestag [Germany’s federal parliament] decided to change the fundamental right to asylum provided for in the German constitution. Afterwards, several “safe third country” regulations came into place, and refugees who were found to have entered Germany through such a safe third country could be incarcerated, which included both children travelling with their parents and UAM. Influenced by this political situation, in 1992 the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) was ratified and became effective in Germany. But Germany reserved the right to interpretative statements on several articles of the CRC. In particular, a serious reservation was voiced regarding its immigration laws which affected UAM' situation (e.g. their living situation) for the following 20 years.

The Sozialgesetzbuch VIII: Kinder- und Jugendhilfe regulates Germany’s child and youth care services nationwide and became effective in 1990. As a federal law, it determines the requirements and conditions for Germany’s care and welfare services for children and youth as well as their legal guardians. The focal point of this framework, pertaining to all young people until the age of 27, is the child’s right to assistance in its upbringing (Köngeter, Schröer & Zeller, 2008). However, where it comes to refugee minors, German immigration laws trumped the Sozialgesetzbuch VIII for many years: UAM were not entitled to enter the child and youth care system per se – instead, the public youth welfare offices in every German municipality still decided on a case-to-case basis whether the young person should be taken into emergency care or not. Furthermore, in the eyes of the Asylbewerberleistungsgesetz [Asylum Seeker Benefits Act] and Aufenthaltsgesetz [Residence Act], minors between the age of 16 and 18 were treated as if they were of legal age. The implications were serious, as it meant that minors

· would live in a collective adult refugee reception center,

· would become subject to adult residence requirements,

· would have no right to engage in education, training or work,

· would have no guardian,

· and were subject to the so-called Dublin procedure, meaning that if the minors entered Germany after reaching another safe EU country, they were sent back to that country of first entry (Espenhorst, 2014).

Public interest groups, particularly those advocating a higher level of rights for child immigrants, pressed Germany to withdraw the abovementioned reservations against the UN CRC from the moment they were articulated. In 2005, first changes were made regarding the legal situation of UAM in Germany. These applied the Sozialgesetzbuch VIII (SGB VIII): from the time of the 2005 reform on, UAM have been explicitly addressed in Section 42 Subs. 1 No. 3 SGBVIII, and local authorities or the municipal Youth Welfare Offices have to take every UAM arriving in their territory into emergency care, i.e. put them in foster care or an appropriate care facility where a thorough care planning procedure will be initiated. The most important change to the 2005 reform was that Section 42 Subs. 1 No. 3 SGBVIII has prior claim to the Asylbewerberleistungsgesetz. The public youth welfare offices thus have the duty to take all 16- and 17-year-old UAM into care no matter what their legal status might be (Deutscher Caritasverband, 2014).

Finally, in July 2010, Germany withdrew its reservations regarding the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child. Since then, UAM have had the same legal entitlements as every German child according to the Child and Youth Care Act. But inter-regional disparities persisted – especially for the 16- to 18-year-olds. In the summer of 2012, the federal government of Germany once more pointed out the prior claim of the Sozialgesetzbuch VIII to any immigration laws until young people reach legal age (Espenhorst, 2014). One year later, in the summer of 2013, the Dublin Regulation was amended (now: Dublin III Regulation, No. 604/2013). It now stipulates that the best interests of the child should be a primary consideration for EU Member States when applying the regulation. Thus, from 2005 until 2013, the national and EU legal framework for UAM has been gradually enhanced.

In 2015, Germany had to deal with a huge influx of refugees in general and UAM in particular. Practitioners and local authorities reported that the child and youth care system was overstretched in certain cities and regions (e.g. Munich, Berlin, Hamburg, Ruhr region) and were especially concerned by the lack of placements and qualified staff, while among politicians the question arose as to who was going to pay for the rising expenses (see Fendrich & Tabel, 2015; Wiesinger, 2017). Although the prior legislative framework, the Sozialgesetzbuch VIII, is a federal German law, it is the responsibility of the municipalities, and more specifically the Public Youth Welfare Offices, to execute it. Government funding for refugee minors was different than for children in care; specifically, it was not each municipality where the refugee minor had arrived that paid the expenses, but each of the 16 Bundesländer. The state of Bavaria in particular claimed this situation was unfair since in 2015, it had to cover more than one third of all the expenses of all UAM arriving in Germany (Rapp, 2017).

As a result, the Sozialgesetzbuch VIII was amended another time in November 2015. The amendment became known as the Umverteilungsgesetz[13] [Relocation Act] and was discussed widely among public interest groups, practitioners and academics. The German federal government's main aim was to ease the burden on youth welfare offices in cities along the transit routes and at the same time to show that the child's best interests were the main goal of the new law (Federal Office for Migration and Refugees, 2016). Its critics doubted that the newly established redistribution system would suit the needs of the children it affected (González Méndez de Vigo, 2017). According to the amendment, currently all UAM are taken into short-term custody (Section 42a SGB VIII) by the Youth Welfare Office of the city where a respective UAM arrives (Section 88a Subs.1 SGB VIII). This Youth Welfare Office then first has to check if family reunification is possible. If this is not the case, the Office has to assess the age of the young person by determining his or her identity (Section 42f SGB VIII). If this is not possible due to missing papers, the Youth Welfare Office assesses the age by (visually) inspecting the young person. There are two criteria for determining the young person’s age. Firstly, at least two professionals (usually social workers at the child and youth welfare office) have to guess the person’s age, and secondly, an interpreter must be brought in to allow the child to define his or her own age. If any doubts remain, the age has to be decided in favor of the young person (Gravelmann, 2016). Medical age assessments are not usual, but the young person or their legal guardian can request such an assessment if they wish, and the accountable Youth Welfare Office can arrange for a medical assessment if doubts cannot be removed in any other way (González Méndez de Vigo, 2017).

If a young person’s age is assessed to be below 18, the Youth Welfare Office must check whether sending the child on to another municipality with enough capacity would be against the best interests of the child (e.g. due to health issues or a possible reunification with siblings) (Section 42b SGB VIII). Critics point out that considering moving a young person (probably against his or her wishes) is in itself against their best interests, while the advocators of this rule state that overcrowded residential care units do not meet the best interests of any child (González Méndes de Vigo, 2017). The redistribution of UAM in Germany follows a particular procedure known as the Königsteiner Schlüssel [Königstein Key][14]. It also applies to every adult refugee. The distribution must take place within two weeks of the young person's arrival and can no longer be processed after one month. In fact, each German state has now developed its own procedure to deal with UAM: while some states distribute the young people among all their municipalities, others have defined certain municipalities that support the young people (Gravelmann, 2016).

In the spring of 2017, the German federal government published the first report evaluating the outcomes of the 2015 amendment. It determined that Bundesländer and municipalities throughout Germany have dealt very well with the challenges of the new situation (Deutscher Bundestag, 2017a). However, public interest groups, such as the Bundesfachverband unbegleitete minderjährige Flüchtlinge, published their own evaluation reports which still criticize the amendments (BumF, 2016). The major point of criticism is the legal requirement that “no legal representative is to be appointed before the redistribution” (BumF, 2015). The second point made against the amendment is that it provoked huge differences in quality between Bundesländer and municipalities – with the result that UAM can have good or bad luck with “their reception center” and “their placement” (Struck, 2017). One fact that almost every critic evaluated as positive is that the 2015 amendment has raised the minimum age for legally effective procedural actions and for actions in a residence and asylum procedure from 16 to 18.

4 Clearance practices and care arrangements

This chapter looks into the procedures that apply to unaccompanied minors once they have entered the child and youth care system. During the last two or three years, practitioners felt a great need for guidance on how to deal with the “new group” appropriately. Thus, some new textbooks (e.g. Gravelmann, 2016), a new compendium (Brinks, Dittmann & Müller, 2017) and special issues in practice-related journals have been published (e.g. sozialmagazin, 2016), including reports about the experiences of practitioners working with UAM[15]. Since research in this field is still scarce, we are limited in debating some of the issues and can mainly give insights into how the procedures are conceptualized.

4.1 The appointment of a legal guardian

In Germany, if parents are unable to exercise parental responsibility – and such is the case with UAM – a legal guardian is appointed.[16] The latest amendments to the Sozialgesetzbuch VIII in November 2015 mean that this legal guardian has to be appointed by the Family Court immediately after the redistribution process.[17] However, the sample in a survey conducted by the national government in 2016 indicated that there is a gap between these statutory provisions and practice: it can last up to four months until a legal representative is appointed (Deutscher Bundestag, 2017b). This practice is problematic as it interferes with the mandate to act in the best interests of the child. The legal guardian is mainly responsible for Vermögenssorge [statutory duty of care for a minor's property] and the Personensorge [personal custody] for the young person, which includes making decisions such as whether an asylum application is lodged, if a therapeutic treatment can be requested, how schooling can be continued and completed, and where the young person is to live after the clearance process (Espenhorst, 2017).

The Family Court decides who ultimately assumes the guardianship. In general, there are three different possibilities for who can take over the legal responsibility of an UAM: firstly a private person or an association on the basis of voluntary work, secondly a person whose profession allows him or her to be a legal guardian and who gets a honorarium and, thirdly, public guardianship by staff from the child and youth welfare office. The law clearly affects the first possibility (German Civil Code (BGB) Section 1791b), because this set-up promises the best rapport between the young person and the legal guardian. However, estimations assume that today around 80% of all UAM have a public guardianship (Laudien, 2017). This is due to the increasing numbers of UAM during recent years and the lack of qualified private persons willing to take on responsibility for an UAM (Espenhorst, 2017). Furthermore, some municipalities report that their staff who are responsible for public guardianship are responsible for too many UAM (more than 50), so the necessary face-to-face meetings (at least once a month) cannot be arranged.

The appointment of a legal guardian ends when the young person attains full age according to the laws in the country of origin or if the family can be reunified (anywhere in Europe) and the parents can assume custody of the young person again.[18] Family reunification within Germany, however, is a politically highly controversial issue, and there are very restrictive regulations in place: only UAM with a refugee status according to the Geneva Convention are eligible to be joined by their parents. All other UAM are excluded from this possibility. Furthermore, are not eligible to be joined by their siblings. If a family comprises several children, the parents have to decide which child to join and which to leave behind, or have to split up. Here, the current restrictions clearly contradict the best interest of the child, as several public interest groups have pointed out (e.g. AFET, 2018).

4.2 Clearance practices after the redistribution process

After the redistribution process that follows the first (transitory) emergency care, the child and youth welfare office that is ultimately in charge of the young person starts the “deeper” clearance process. Therefore, the young person has to be accompanied to the new place by a social worker or another trustworthy person and his or her file is referred electronically from the first child and youth welfare office to the second one.[19] The clearance process that then follows aims to define the needs of the young person (according to Section 42 SGBVIII): Was anything overlooked in the previous process? Might a family reunification be possible after all? Who could be appointed as a legal guardian? Would it meet the needs of the young person to stay in a foster family or a residential group home after the clearance process, or might assisted living be a good option? How can language skills be gained and improved? What are the options in regard to education? Are there any therapeutic requirements? Will an asylum application be lodged? All these questions are assessed and finally decided at a care planning conference where the UAM, the legal guardian, the responsible staff from the child and youth welfare office and a staff from the NGO involved usually come together (Knuth, Kluttig & Uhlendorf, 2017).

During recent years different clearance practices have been established throughout Germany. Larger cities tend to have clearance houses only for UAM, while, in more rural areas, short-term custody groups for youth are more common, or short-term custody placements within regular group homes might even be the model. During the high influx in 2015 and 2016 new “emergency shelters” were also opened e.g. in (sometimes former) hotels or hostels (Deutscher Bundestag, 2017b). A non-representative online survey conducted by the BumF shows that in 2016 specialized clearance houses were the most likely placements (BumF, 2016). The clearance process is supposed to be finished within three months, but reports from practice (Caritasverband) show that it can also take longer, which means up to six months, and sometimes even longer than that (Deutscher Bundestag, 2017b).

Social workers are responsible for the clearance procedure and take care of the young people for 24 hours a day, seven days a week. As we know from reports and explorative research, they and the young people face different major challenges during that time: Firstly, the so-called language issue: the majority of German child and youth care workers do not speak any language which is the mother tongue of any UAM and the young people hardly know any German when they arrive. Therefore, communication is described as a real challenge. For important appointments, e.g. the care planning conference, an interpreter can be appointed, and sometimes the communication barrier can be resolved by using a third language such as English or French or by the help of peers who already know more German and who can translate back and forth (Gravelmann, 2016). The latter possibility is criticized heavily as the peers can be overwhelmed by this task. Secondly, in the understanding of the law, the clearance procedure is meant to set the course for further intervention(s). Therefore professionals are supposed to provide a secure place but not establish (intensive) relationships. This does not necessarily relate to the needs of the young people, because many of them wish to finally find a home (Akbasoglu, El-Mafaalani, Heufers, Karaoglu & Wirtz, 2012). Furthermore, the professionals will not be able to determine the best means of helping the child without establishing a relationship based on trust. Thirdly, some young people arrive with the intention to start work immediately and help their families back home either by sending them money or by finding a way for them to come to Germany as well. These expectations clash with the principles of child and youth care and the given possibilities within the asylum law and cause a challenge for both the young people and the professionals (Knuth, Kluttig & Uhlendorf, 2017). Fourthly, many of the UAM have experienced situations during their flight that make them seem very mature in many aspects. Hence, there is a danger of underestimating the needs of the UAM and subsequently not initiate sufficiently supportive care (Gravelmann, 2016).

4.3 Care arrangements

After the clearance procedure, the vast majority of the UAM are placed in a residential group home (Section 34 SGBVIII), while some are placed in foster families or so-called host families (Section 33 SGBVIII). Unfortunately, no exact data is available on who is placed where, but results from an explorative study suggest that less than 15% of the UAM even fit the criteria for a foster care arrangement (Betscher & Szylowicki, 2017).[20] Group homes usually provide space for eight to ten young people, who are supported by social workers/social pedagogues working in shifts so that 24-hour support is guaranteed seven days a week. Young people who are already quite independent can move to forms of assisted living, which includes a choice of either living on their own in an apartment or sharing an apartment with one or two friends while a social worker drops by for support a fixed amount of time per week (e.g. one hour a day or three times a week, depending on the individual support that is needed).

One important issue that is discussed frequently among professionals is whether UAM are to be placed in group homes that are for UAM[21] only or integrated into pre-existing groups with young people who have grown up in Germany (Detemple, 2013). While some professionals and social service providers stress the idea that UAM have “special needs” that can be met most adequately in specialized group settings, others emphasize the opportunity of mutual learning within integrated group home settings. In fact, the German Child and Youth Care Act stresses that not only the needs but also the wishes of the young people must be taken into account when it comes to the decision to find an appropriate group home.[22] In practice, in recent years hardly any UAM has probably had a choice of which group they were placed in because there was a significant lack of placements, even though new groups (for UAM only) and even provisional arrangements were opened. Data collected by the Catholic umbrella organization on their own group homes (Bundesverband katholischer Einrichtungen und Dienste der Erziehungshilfen e.V.) show that in 2016 almost 80% of UAM sent there were placed in a specialized group (Deutscher Bundestag, 2017b). Practitioners and service providers describe the integration of the UAM into the existing child and youth care system and the qualification/further education of (additional) staff as a challenge. One issue here is that the German staff[23] is not yet that familiar with the concept of cultural sensitivity (Hansbauer & Alt, 2017).

According to an explorative study in one of the German Bundesländer (Baden-Württemberg), most of the UAM wish and plan to stay in Germany after leaving the child and youth care system (Kohlbach, 2015). Therefore, one key focus of residential care has to be to prepare the young people for independency and to support their educational career. Unfortunately, the German school system is not easy to access for UAM. The main reason for this is that compulsory schooling ends when young people turn 16. German youth older than that either attend Gymnasium [academic high school] or Berufsschule [vocational school] (often only for one day a week) during their two or three years of vocational training. Due to the language issue, UAM rarely have the chance to enter this schooling system directly. Therefore, most Bundesländer[24] nowadays provide special “language”, “integration” or “welcome” classes (Gravelmann, 2016), but their quality and accessibility can vary massively e.g. between certain rural and urban areas, and some group homes therefore provide additional language courses.

4.4 UAM as care leavers

Unfortunately, when it comes to the question of research on leaving care, Germany lags behind other countries, so there is little knowledge about care leavers in general (Köngeter, Schröer & Zeller, 2012), and even less about UAM as care leavers in particular.

First of all, however, one important fact is that the German Child and Youth Welfare Act offers the possibility to support young people who were previously placed in residential care until they turn 21.[25] This can be either in the form of (single or group) accommodation with support from social workers (assisted living) or with non-residential assistance (for example, counselling). If a young person wishes to be supported longer than the age of majority, he or she has to apply at the local authority (there is no legal guardian any more). Statistical data show that support for young adults is not generally granted very often and, if they are granted it, often only lasts an additional six months (Sievers, Thomas & Zeller, 2015). Figure 2 in Chapter 2 of this paper offers an indication of how many young adults are supported by the child and youth care system, although this day-by-day data is not very precise. However, it seems obvious that there are not many UAM who receive support as young adults according to Section 41 SGB VIII. Between the middle and the end of 2016, the numbers even decrease, although one would expect them to increase compared to the number of UAM who aged out of residential care (Section 34 SGB VIII).

In 2015 Noske published an expert report on UAM as Care Leavers as part of a European project that worked on the concretization of the term “durable solutions” (UNHCR, 2005). The results show that UAM who cannot secure their legal status are particularly afraid of the future and feel lost once the time in residential care ends. If UAM have to leave residential care with no future perspective, they find themselves in a collective adult refugee reception center, maybe with a deportation in the end, or in the streets or on the journey to another European country (Andernach & Tavangar, 2014). Obviously, there are also those who succeed in living independently, finishing their education, and starting a job. No figures are available on how many go which way, but estimations assume that the latter group (the “successful one”) is much smaller than one would expect. Among not only professionals but also public interest groups, the question arises of whether it makes sense to spend a lot of money on the young people and their integration while in the child and youth care system, only to pay for their deportation the next moment.

5 Conclusions and prospects in the light of German research on UAM

The information gathered for and presented within this paper shows that various political, juridical and professional developments have taken place. First of all, the number of unaccompanied minors seeking protection in Germany rose significantly between 2009 and 2016, which led to greater recognition of the issue. In regard to the legal situation of UAM, Germany’s withdrawal of its reservations regarding the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child definitely made a change: since then, UAM have had the same legal entitlements as every German child according to the Child and Youth Care Act. Up to this point at least, the legal developments could be described as a ‘success story’. However, we do not have a clear evaluative picture yet of all the possible consequences of the latest amendments regarding the Umverteilungsgesetz [Relocation Act], and we do have political forces that keep questioning whether UAMs should really have the same legal entitlements as German children. The latest issue to be discussed in this respect – after the restrictions in regard to family reunification – is that of the age assessment procedure and the suggestion of using a medical examination as a standard procedure to better identify fake refugee minors. Moreover, the situation of UAM as care leavers can clearly be seen as very problematic due to the increasing restrictions in the asylum system for adult refugees.

As already mentioned in the introduction to this article, Germany does not have a tradition of refugee studies, and neither have there been many studies on UAM. For many years it seemed as if refugees were an undesirable political topic; this was connected to Germany’s long standing self-image of not being an immigration country. It seemed as if this approach was reflected in very few research activities and no explicit funding opportunities for refugee studies. After the so-called European refugee crisis, for one thing this changed and a lot of research has opened up to topics that are related to refugee studies[26], but apart from that research on UAM is still very scarce (Gravelmann, 2016).

Besides the statistical data already presented, there have been some qualitative studies. Most of them were conducted for qualification reasons – either Master’s or PhD theses (see Stauf, 2012; Zimmermann, 2012; Detemple, 2013; Hargasser, 2015; Zito, 2015). One research focus is on UAM and trauma (see Zimmermann, 2012; Hargasser, 2015; Zito, 2015), while other studies focus more on the interface between UAM and the services provided by the child and youth care system (e.g. Detemple, 2013). Additionally, there are a few evaluation studies on either specific services for UAM, such as a certain Clearance House in the Ruhr Area (Akbasoglu, El-Mafaalani, Heufers, Karaoglu & Wirtz, 2012), services for UAM in a certain region or state, such as Baden-Württemberg (Kohlbach, 2015) or services for UAM provided by a certain umbrella organization (Herrmann & Macsenaere, 2017).

All in all, research clearly lags behind the needs. Specifically, there is a complete lack of any large-scale and longitudinal studies so far.

As already mentioned, during recent years a larger body of practice-related literature has emerged (see Gravelmann, 2016) with many titles focussing on how to deal with traumatized UAM in particular (see Kühn & Bialek, 2017; Zito & Martin, 2016; Quindeau & Rauwald, 2017). On one side this reflects on the needs of the practitioners, many of them being new to the field. On the other there is a danger that this might lead to a restricted perspective on the phenomenon of UAM. Therefore, in practice as well as in research, there is a future need to emphasize not only UAM' vulnerability but also their agency (Schmittgen, Köngeter & Zeller, 2017).

References

AFET (2018). Stellungnahme des AFET-Bundesverbandes für Erziehungshilfe zur Situation unbegleiteter minderjähriger Ausländer, unter besonderer Berücksichtigung des Koalitionsvertrags und des Verteilverfahrend nach § 42b SGB VIII. Retrieved May 2015, from, http://www.afet-ev.de/aktuell/AFET_intern/2018/Stellungnahme-AFET-UMA-3.Mai-2018.pdf?m=1525344982

Akbasoglu, S., El-Mafaalani, A., Heufers, P., Karaoglu, S., & Wirtz, S. (2012). Unbegleitete minderjährige Flüchtlinge im Clearinghaus. Dortmund/Düsseldorf. Retrieved May 2015, from: http://www.isf-ruhr.de/publikationen/.

Andernach, L., & Tavangar, P. (2014). Junge Flüchtlinge in der Volljährigkeitsfalle. Forum Erziehungshilfen, 20(3), 155–156.

Berthold, T. (2014). In erster Linie Kinder. Flüchtlingskinder in Deutschland. Retrieved May 2015, from: https://www.unicef.de/blob/56282/fa13c2eefcd41dfca5d89d44c72e72e3/fluechtlingskinder-in-deutschland-unicef-studie-2014-data.pdf.

Betscher, S. & Szylowicki, A. (2017). Unbegleitete minderjährige Flüchtlinge in Gastfamilien. In S. Brinks, E. Dittmann & H. Müller (Eds.), Handbuch unbegleitete minderjährige Flüchtlinge (pp. 175–185). Frankfurt/Main: IGfH-Eigenverlag.

Brinks, S., Dittmann, E., & Müller, H. (2017). Handbuch unbegleitete minderjährige Flüchtlinge. Frankfurt am Main: IGfH-Eigenverlag.

BumF (2015). Kritik an der Bezeichnung "unbegleitete minderjährige Ausländer_in" Retrieved January 2016, from http://www.b-umf.de/images/Kritik_Begriff_umA.pdf.

BumF (2016). Die Aufnahmesituation unbegleiteter minderjähriger Flüchtlinge in Deutschland. Erste Evaluation zur Umsetzung des Umverteilungsgesetzes. Retrieved December 2017, from http://www.b-umf.de/images/aufnahmesituation_umf_2016.pdf.

BumF (2017). Zwei-Klassen-Jugendhilfe für junge Flüchtlinge in Bayern geplant: Ausführungsgesetz soll zeitnah beschlossen werden. Retrieved December 2017, from http://www.b-umf.de/images/2017_13_09_PM_Bayern_SGBVIII.pdf.

Detemple, K. (2013). Zwischen Autonomiebestreben und Hilfebedarf. Unbegleitete minderjährige Flüchtlinge in der Jugendhilfe. Baltmannsweiler: Schneider Verlag Hohengehren.

Deutscher Bundestag (2015). Antwort der Bundesregierung auf die Große Anfrage der Abgeordneten Luise Amtsberg, Beate Walter-Rosenheimer, Dr. Franziska Brantner, weiterer Abgeordneter und der Fraktion BÜNDNIS 90/DIE GRÜNEN. Retrieved November 2016, from http://dipbt.bundestag.de/doc/btd/18/055/1805564.pdf.

Deutscher Bundestag (2017a). Bericht über die Situation unbegleiteter ausländischer Minderjähriger in Deutschland. Retrieved January 2018, from http://dipbt.bundestag.de/doc/btd/18/115/1811540.pdf.

Deutscher Bundestag (2017b). Antwort der Bundesregierung auf die Kleine Anfrage der Abgeordneten Beate Walter-Rosenheimer, Luise Amtsberg, Dr. Franziska Branter. Daten zu unbegleiteten minderjährigen Flüchtlingen. Retrieved January 2018, from http://dip21.bundestag.de/dip21/btd/18/110/1811080.pdf.

Deutscher Caritasverband (2014). Unbegleitete minderjährige Flüchtlinge in Deutschland. Rechtliche Vorgaben und deren Umsetzung. Freiburg im Breisgau: Lambertus .

Espenhorst, N. (2014). Unbegleitete minderjährige Flüchtlinge zwischen Jugendhilfe - und Ausländerrecht. Soziale Arbeit, 10/11(63), 395–401.

Espenhorst, N. (2017). Die rechtliche Vertretung von unbegleiteten minderjährigen Flüchtlingen. In S. Brinks, E. Dittmann & H. Müller (Eds.), Handbuch unbegleitete minderjährige Flüchtlinge (pp. 158–165). Frankfurt/Main: IGfH-Eigenverlag.

Espenhost, N. & Noske, B. (2017). Asyl- und Aufenthaltsrecht. In S. Brinks, E. Dittmann & H. Müller (Eds.), Handbuch unbegleitete minderjährige Flüchtlinge (pp. 49-59). Frankfurt/Main: IGfH-Eigenverlag.

Eurostat (2018). Asylum applicants considered to be unaccompanied minors. Retrieved April 2018, from Asylum and Managed Migration Data: http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/tgm/table.do?tab=table&init=1&language=en&pcode=tps00194&plugin=1.

Federal Office for Migration and Refugees (2016). Migration, Integration, Asylum. Political Developments in Germany 2015. Annual Policy Report by the German National Contact Point for the European Migration Network. Retrieved January 2017, from https://www.bamf.de/SharedDocs/Anlagen/EN/Publikationen/EMN/Politikberichte/emn-politikbericht-2015-germany.pdf?__blob=publicationFile.

Fendrich, S., & Tabel, A. (2015). Hilfen zur Erziehung auf neuem Höchststand - eine Spurensuche. KomDat Jugendhilfe, 18(3), 1–4.

Fili, A., & Xythali, V. (2017). The Continuum of Neglect: Unaccompanied Minors in Greece. Social Work & Society, forthcoming.

González Méndez de Vigo, N. (2017). Gesetzliche Rahmung: Unbegleitete minderjährige Flüchtlinge im SGB VIII. In S. Brinks, E. Dittmann & A. Müller (Eds.), Handbuch unbegleitete minderjährige Flüchtlinge (pp. 20–48). Frankfurt/Main: IGFH-Eigenverlag.

Grasshoff, G. (2017). Junge Flüchtlinge. Eine neue Herausforderung für die Kinder- und Jugendhilfe? Sozialmagazin, (3–4), 56-61.

Gravelmann, R. (2016). Unbegleitete minderjährige Flüchtlinge in der Kinder- und Jugendhilfe. Orientierung für die praktische Arbeit. München, Basel: Reinhardt.

Hansbauer, P., & Alt, F. (2017). Heimerziehung und betreutes Wohnen. In S. Brinks, E. Dittmann & H. Müller (Eds.), Handbuch unbegleitete minderjährige Flüchtlinge (pp. 186 - 193). Frankfurt am Main: IGfH-Eigenverlag.

Harder, A. T., Zeller, M., López, M., Köngeter, S., & Knorth, E. (2013). Different sizes, similar challenges: Out-of-home care for youth in Germany and the Netherlands. Psychosocial Intervention, 22(3), 203–213.

Hargasser, B. (2015). Unbegleitete minderjährige Flüchtlinge. Sequentielle Traumatisierungsprozesse und die Aufgaben der Jugendhilfe. Frankfurt am Main: Brandes&Apsel.

Herrmann, T., & Macsenaere, M. (2017). Minderjährige Flüchtlinge sprechen gut auf Hilfen an. neue caritas (1), 24–27.

Knuth, N., Kluttig, M., & Uhlendorff, U. (2017). Clearingverfahren für unbegleitete minderjährige Flüchtlinge. In S. Brinks, E. Dittmann & H. Müller (Eds.), Handbuch unbegleitete minderjährige Flüchtlinge (pp. 104–112). Frankfurt/Main: IGfH – Eigenverlag.

Kohlbach, C. (2015). Forschungsbericht der Studie zum Umgang mit unbegleiteten minderjährigen Flüchtlingen in Baden-Württemberg. Retrieved December 2017, from http://www.paritaet-bw.de/fileadmin/user_upload/Fachbereiche/Migration/Unbegleitete_minderjaehrige_Fluechtlinge/Studie/Der_PARITAETische_BW_2015_UMF_Forschungsbericht.pdf.

Köngeter, S., Schröer, W., & Zeller, M. (2008). Germany. In E. Munro & M. Stein (Eds.), Young People's Transitions from Care to Adulthood. International Research and Practice (64-78). London/Philadelphia: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Köngeter, S., Schröer, W., & Zeller, M. (2012). Statuspassage "Leaving Care": Biographische Herausforderungen nach der Heimerziehung. Diskurs Kindheits- und Jugendforschung, 7(3), 261–276.

Kühn, M., & Bialek, J. (2017). Fremd und kein Zuhause. Traumapädagogische Arbeit mit Flüchtlingskindern. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht GmbH & Co. Kg.

Laudien, K. (2017). Die Vormundschaft von minderjährigen Flüchtlingen. Jugendhilfe, 55(2), 125–130.

Müller, A. (2014). Unbegleitete minderjährige in Deutschland. Retrieved May 2015, from http://www.diakonie.de/media/BAMF_WP_60_UMF_in_Deutschland_2014.pdf.

Noske, B. (2015). Die Zukunft im Blick. Die Notwendigkeit, für unbegleitete minderjährige Flüchtlinge Perspektiven zu schaffen. Retrieved October 2015, from Berlin: http://www.b-umf.de/images/die_zukunft_im_blick_2015.pdf.

Parusel, B. (2017). Unaccompanied minors in the European Union - definitions, trends and policy overview. Social Work and Society, 15(1). 1-15.

Quindeau, I., & Rauwald, M. (Eds.) (2017). Soziale Arbeit mit unbegleiteten minderjährigen Flüchtlingen. Traumapädagogische Konzepte für die Praxis. Weinheim Basel: Belz Juventa.

Rapp, C. (2017). Vorläufige Inobhutnahme von unbegleiteten Minderjährigen: Ein Praxisbericht aus Sicht des Stadtjugendamtes München. Jugendhilfe, 55(1), 26–34.

Roßkopf, R. (2017). Asylverfahren (und andere aufenthaltssichernde Maßnahmen). 2017, 5(2), 117–124.

Schmittgen, J., Köngeter, S., & Zeller, M. (2017). Transnational networks and border-crossing activities of young refugees. Transnational Social Review, 7(2), 1–7.

Sievers, B., Thomas, S., & Zeller, M. (2015). Jugendhilfe - und dann? Zur Gestaltung der Übergänge junger Erwachsener aus stationären Erziehungshilfen. Frankfurt am Main: IGfH-Eigenverlag.

Sozialmagazin (2016). Flucht und Asyl, 41(3-4), Weinheim, Beltz: Juventa.

Statistisches Bundesamt (2017). Statistiken der Kinder- und Jugendhilfe. Vorläufige Schutzmaßnahmen. Retrieved December 2017, from Destatis: https://www.destatis.de/DE/Publikationen/Thematisch/Soziales/KinderJugendhilfe/VorlaeufigeSchutzmassnahmen5225203167004.pdf?__blob=publicationFile.

Stauf, E. (2012). Unbegleitete minderjährige Flüchtlinge in der Jugendhilfe Bestandsaufnahme und Entwicklungsperspektiven in Rheinland-Pfalz. Mainz: ism.

Struck, N. (2017). Jugendhilfepolitische Entwicklungsperspektiven. In S. Brinks, E. Dittmann & H. Müller (Eds.), Handbuch unbegleitete minderjährige Flüchtlinge (pp. 312–324). Frankfurt am Main: IGfH-Eigenverlag.

UNHCR & Unicef. (2014). Safe and Sound. What States can do to ensure Respect for the best Interests of Unaccompanied and Separated Children in Europe. Retrieved December 2017, from: http://www.refworld.org/pdfid/5423da264.pdf.

UNHCR (2005). Finding durable solutions. Retrieved January 2017, from http://www.unhcr.org/4371d1a60.html

Wiesinger, I. (2017). Rechtliche Rahmenbedingungen und Gestaltungsaufträge an die Kinder- und Jugendhilfe. In I. Quindeau & M. Rauwald (Eds.), Soziale Arbeit mit unbegleiteten minderjährigen Flüchtlingen. Traumapädagogische Konzepte für die Praxis (pp. 28–41). Weinheim, Basel: Beltz Juventa.

Zimmermann, D. (2012). Migration und Trauma pädagogisches Verstehen und Handeln in der Arbeit mit jungen Flüchtlingen. Gießen: Psychosozial-Verlag.

Zito, D. (2015). Überlebensgeschichten. Kindersoldatinnen und -soldaten als Flüchtlinge in Deutschland. eine Studie zur sequentiellen Traumatisierung. Weinheim and Basel: Beltz Juventa.

Zito, D., & Martin, E. (2016). Umgang mit traumatisierten Flüchtlingen. Ein Leitfaden für Fachkräfte und Ehrenamtliche. Weinheim and Basel: Beltz Juventa.

Author´s

Address:

Prof. Dr. Maren Zeller

Trier University

Universitätsring 15,

54296 Trier, Germany

+49(0)6515612012368

zeller@uni-trier.de

Author´s

Address:

Prof. Dr. Philipp Sandermann

Leuphana University of Lüneburg

Universitätallee 1, 21335 Lüneburg, Germany

+49(0)41316772381

sandermann@leuphana.de