Unaccompanied Minors in France and Inequalities in Care Provision under the Child Protection System

Isabelle Frechon, Laboratoire Printemps, UVSQ-Paris Saclay, Associate researcher, Institut national d’études démographiques (INED-UR6)

Lucy Marquet, Laboratoire Clersé, Université Lille 1, Associate researcher, Institut national d’études démographiques (INED-UR6)

1 Introduction

The issue of unaccompanied minors (UAM) is frequently front-page news in France, against a background of economic recession and increasing flows of migrants through Europe. The worry these situations arouse combines with concerns about the fate of unaccompanied minors. Since 2010, the legislation has been constantly changing to adapt care arrangements to the increase in numbers of unaccompanied minors entering the country. In France, UAM may be taken into care by the child protection services and go into the system for asylum seekers, although this is much less common. In 2016, 8054 new UAM were taken into care by the child protection authorities and only 474 were processed as asylum seekers. As at end 2016, UAM represented 8% of minors in care. However, these figures do not include UAM who were not acknowledged as such by the child protection services.

The French child protection system is organized by département. Each of the 96 départements in Metropolitan France and the five overseas French départements finances and conducts its own child protection policy within the framework of the national legislation. The cost of care provision for UAM is thus the core issue, far ahead of the question of what support they are given.

Knowledge of this population has improved in recent years, with the establishment of national statistics and more surveys and research on the subject. However, the research mainly concerns interpretation of the law and the gap between the care and support UAM are entitled to in law and what is provided. A resource center for researchers and professionals pools information on the UAM problem.

Not much is known about the living conditions of UAM in France at present. However, we have conducted a major longitudinal survey on young people’s transition to independent life after being in care (Frechon & Marquet, 2016). That survey, with two waves of data gathering by questionnaire, gathered testimony from 1600 youngsters aged 17 to 20 in care (wave 1) and 750 of the same youngsters 18 months later (wave 2). The sample was representative of young people in care in two large regions of France, and 29% of them were or had been UAM. We have used the data from that survey to present novel results on the child protection services’ provision of care to UAM compared to other minors in care.

Before presenting the results of the ELAP study, we summarize the relevant definitions, the national statistics and the assessment system that filters and selects at each stage to end with the population recognized by the authorities as UAM.

2 Unaccompanied minors: definitions and basic data

2.1 Several different terms in French for unaccompanied minors

Since the influx of UAM from Southeast Asia in the late 1970s (Rodier 1986) and even more since the late 1990s, France has used the terms mineur isolé étranger [foreign lone minor]. There is no specific mention of unaccompanied minors in the child protection laws of 5 March 2007 and 14 March 2016, but they are covered by the broader category of minors temporarily or definitively deprived of the protection of their family. The term mineurs non accompagnés [unaccompanied minors] is used at the behest of the Justice Ministry, for the purposes of European harmonization, but it is little used in ordinary parlance so far. Some official reports also use the term jeunes isolés étrangers [lone young foreigners] to also take into account young people aged 18 to 20 who entered the child protection system as mineur isolé étranger and are still in care under a Young Adult’s Contract, a welfare measure for young people up to their 21st birthday[1].

Having no legal status, the term mineur isolé étranger [lone young foreigners] has no explicit definition in French law. However, definitions can be found in various official reports such as the 2010 Senate report:

“A lone foreign minor is a person under the age of 18 who is not in their country of origin and yet is not accompanied by a guardian or person exercising parental authority, in other words has no one to protect them and take important decisions about them.” (Debré 2010)

There are also definitions in reports by non-profit bodies that care for these children or inform them of their rights. A mineur isolé étranger is a

“person under the age of 18 who does not have French nationality and is in France, separated from their legal representatives. Because they are minors they are legally incapable, and without a legal representative they are on their own and in need of protection.” (France Terre d’Asile 2013).

Whereas the European Council’s definition specifies that UAM are minors from non-EU countries, the French approach makes no restriction as to the child’s country of origin and included all foreign minors, regardless of nationality (InfoMIE 2014).

2.2 More UAM in the child protection system than in the asylum-seekers’ system

The following statistics do not include unaccompanied minors who have not been officially recognized as such.

The data come from two main sources which partly overlap: the administrative and legal child protection services and the authorities responsible for foreigners.

Data from the administrative and legal child protection services

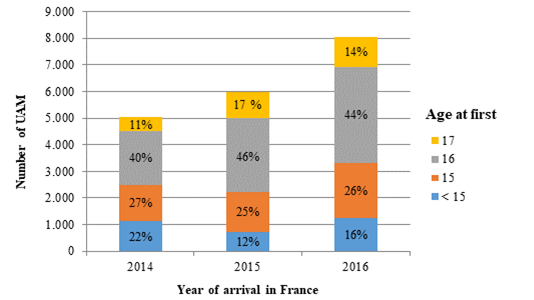

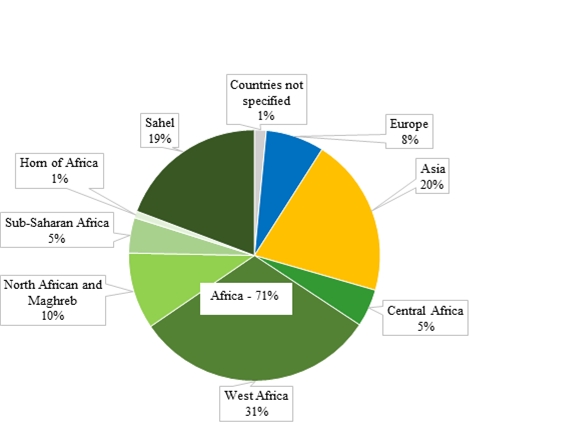

Until 2013 there was no national statistical monitoring system compiling data on unaccompanied minors. Since 2013, the Mission des Mineurs Non accompagnés (MMNA) [UAM mission] regularly issues figures on the number of UAM placed in the custody of the child welfare services Aide Sociale à l’Enfance or ASE [child welfare services] by the courts. In terms of ‘flows’, 8054 new UAM arrivals were recorded in 2016, 34% more than in 2015 and 215% more than in 2013, the year the MMNA came into operation. The proportion of girls declined between the two periods, from 10% to 5%. Conversely, age on being taken into care altered only marginally: 41% of UAM were taken into care before the age of 16, 59% at age 16 and after. The majority of UAM arriving in France are from Africa, particularly the French-speaking countries of West and North Africa. However, since the end of 2016, an increase in the numbers of minors arriving from Afghanistan, India and Bangladesh has been recorded (MMNA 2017).

Figure 1: Number of UAM arriving each year, by age on first being taken into care

Source: MMNA, 2017

Figure 2: Countries of origin of UAM

Source: MMNA, 2017

In terms of ‘stocks’, there were 13,008 unaccompanied minors in the care of the child protection services at 31 December 2016, compared to 10,194 at 31 December 2015. It is reckoned that this figure could reach 25,000 in 2017 (Doineau & Godefroy, 2017). According to our 2016 calculations, 8% of children in care are UAM.

Data from the authorities responsible for foreigners

Not all unaccompanied minors apply for asylum, either for reasons of ignorance or because they are not eligible. In recent years, the migration of unaccompanied minors into France seems to have been more a matter of economic migration (forced to varying degrees) than the flight of refugees (Doineau & Godefroy, 2017). Moreover, minors do not need to apply for asylum in order to obtain the protection of the child welfare services. In 2016, the number of asylum applicants considered to be unaccompanied minors was 474, of whom 86% were aged 16-17 at the time they applied and 24% were girls. Most of these applicants were minors from Afghanistan (28%), Democratic Republic of Congo (10%), Sudan (8%), Syria (5%), and Guinea (5%) (OFPRA 2017). These 474 asylum seekers (the figure is taken from Eurostat, 2017) are included in the 8054 new UAM taken into care by the child protection services that year.

2.3 Fewer and fewer girls among UAM

Because the system of statistics on those assessed and taken into care as UAM or not was only set up in 2013, it is not possible to analyze time trends in the breakdown of UAM in France by nationality from this source. However, a study provides a picture of UAM in care between 1999 and 2001 (Etiemble 2002). The study covered half the départements of France. During those three years, there was a fairly spectacular change in the pattern of UAM in France, with a big increase in total numbers. There was a higher proportion of girls than there is now (20% in 2000, 5% in 2016). The pattern of geographical origins has also changed a lot since then. While Romanians and Chinese were among the largest sub-groups in the early 2000s, these nationalities are virtually absent from the statistics on UAM placed in care since 1 June 2013. Romanian minors in France today seem more often to be with a migrant family, mainly Roma families. Even when they are identified by the authorities and are not accompanied by their parents, these minors are difficult to settle within the care system. Being either with their families or reluctant to accept care, these children are absent from the UAM data, but this does not mean they are not vulnerable and in need of protection (IGAS 2014).

2.4 UAM more vulnerable than other children in care owing to lack of contact circle

A survey among 1600 young people in care aged 17 to 20, of whom 29% were UAM, allows us to look at the social, educational and family characteristics of unaccompanied minors in comparison to other youngsters in care (Frechon & Marquet, 2016). This longitudinal study of the transition to independence of children in care Étude Longitudinale sur l’Autonomisation des jeunes Placés (ELAP) was conducted in 2013-2014 in seven heavily urbanized départements in two regions of France that house almost half of UAM (Ministère de la Justice 2013).

While 88% of UAM in the ELAP survey were boys, among other 17-year-olds in care there were as many girls as boys.

The absence of a parent (biological mother, father) from the child’s entourage is a reality for children in care: the parents are dead, or the child never knew them, or they are no longer in contact with them. Whereas 96% of 17-year-olds in the general population still have both parents in their lives, this was the case for 36% of non-UAM in the ELAP study and 25% of the UAM. The proportion of non-UAM 17-year-olds in care who were either fatherless, motherless or orphaned was 22%, much higher than for the general population (4%); of unaccompanied minors, nearly half had lost at least one parent (34% had lost one parent and 13% had lost both). On the other hand, UAM were on good terms with their parents if they were alive and their whereabouts known; this was less the case for non-UAM. But only 44% of UAM had been in touch with at least one parent (by phone or Internet) in the previous month; that figure was 67% for non-UAM in care.

The UAM also had smaller friendship circles than the other juveniles in care: 15% said they had no very good friends, compared to 6% of the non-UAM.

Being so far from their family at home also makes UAM more socially vulnerable: 80% of the UAM in the study knew nobody who could help them out if they had financial problems, compared to 30% of the non-UAM.

In the course of their migrations before being taken into care in France, these young people had been through very tough times as regards accommodation; 65% of the UAM said there had been times when they did not know where to stay or where to sleep. For the non-UAM this figure was 18%. 53% of UAM had slept in the street compared to 8% of non-UAM and 33% had been accommodated by voluntary organizations such as the French Red Cross or France Terre d’Asile. In many cases that was the initial reception stage when their situation was assessed on arrival in France.

The ELAP study does not inform us about the young people’s state of health but does tell us how they feel about it. They were asked “Compared to people of your age, would you say your health is: not at all satisfactory, not very satisfactory, fairly satisfactory or very satisfactory?” The question being phrased in this way, it is hard to tell who these youngsters are comparing themselves with. Probably their peers. 61% considered their state of health very satisfactory (compared to 55% of non-UAM) and 30% fairly satisfactory (vs. 34%). But 84% of the UAM had consulted a doctor for some physical health problem in the previous 12 months (vs. 72% of non-UAM) and 34% had consulted for a psychological problem in the previous 12 months (vs. 32%). 5% of the UAM in care had no health coverage or were not aware that they had; the proportion of non-UAM was the same.

Voluntary bodies and the psychologists concerned often decry the inadequate provision of psychological care for young migrants. Beneath their apparent good health and unobtrusive symptoms, these young UAM are particularly vulnerable (Group of psychologists in the Nord département, 2016). A medical thesis records all the physical and psychological pathologies identified in a population of 143 UAM in a region of southwestern France. The total prevalence of hepatitis B (acute + chronic), as indicated by the presence of anti-HBc antibodies, was 28%. 45% (64 of the 143 UAM) presented clinical pictures compatible with post-traumatic stress; 52% (n=75/143) said they had experienced psychologically traumatic events; 41% (n=59/143) complained of sleep disorders; 34% (n=49/143) presented symptoms of depression and 29% presented dental caries (Baudino 2015).

3 Legal framework for establishing UAM status

3.1 Protective process involves foreigners’ rights and child protection law

Article 20 of the UN Children’s Rights Conventions states that “a child temporarily or permanently deprived of his or her family environment, or in whose own best interests cannot be allowed to remain in that environment, shall be entitled to special protection and assistance provided by the State.” Article 24-1 of the European Union’s Charter of Fundamental Rights states that “children shall have the right to such protection and care as is necessary for their well-being.” Under these conventions, care for unaccompanied minors in France is covered by Article 374 of the Code Civil:

“If the health, safety or morals of a non-enfranchised minor is endangered or if the conditions for their education or physical, emotional, intellectual and social development are seriously compromised, the courts may order educational assistance measures.”

However, to be recognized as UAM they must first go through a series of assessments, each step sorting the eligible from the ineligible.

At the border, foreign minors seeking to enter the country are subject to the same rules as adults (REM 2014). If they cannot produce the documents required of adults (visa, passport, other documents depending on the reason for their stay), they may be denied entry. Under Article 31 of the Geneva Convention, asylum seekers can enter France without having to present the documents normally required. This principle obviously applies to minors seeking asylum in France. UAM can be kept in a holding area for a maximum of 20 days while their asylum request is examined or if they do not fulfil the conditions for entry.

Since foreign minors are not required to possess a residence permit, UAM apprehended when they are already in the country do not go through this stage. Once it has been clearly established that they are minors and are on their own (see below), they fall under the mainstream legislation on child protection. Each UAM is allocated an ad hoc guardian[2] who is responsible for helping them and representing them in the administrative and legal proceedings concerning their stay in the holding area, their entry into France or their asylum application. Part of the ad hoc guardian’s job is to identify whether the minor’s health, safety or morals are endangered. If danger is detected, the ad hoc guardian can apply to the public prosecutor or tell the UAM that they can apply directly to the children’s judge to be taken into care under the child protection legislation.

In France, young people recognized as UAM are the responsibility of the départements since the fall under the mainstream child protection laws. However, most UAM arrive in one of four départements: Paris, Seine-Saint-Denis, Nord and Pas-de-Calais. In 2002, to avoid the child protection system being overwhelmed, it was decided to spread the UAM around the country. A circular of 31 May 2013 introduced a nationwide clearing system for initial reception, assessment and referral of UAM. The system’s implementation procedures are set out in an agreement[3] between central government and the départements of Metropolitan France. These arrangements were then ratified by Article 48 of the child protection law of 14 March 2016 which gives the justice minister the task of “setting the objectives for a proportional distribution among the départements of care provision for minors temporarily or permanently deprived of the protection of their families, according to demographic and geographical distance criteria.”

This system is also intended to harmonize practices among départements as regards the different stages: reception, assessment, referral and care. Child protection is performed in the département where the UAM was found or came forward to ask for protection. Central government pays for this stage for five days, the duration of emergency accommodation allowed for in the circular. The département is paid 250 € per person per day.

An assessment protocol sets out the methods for assessing age and whether the minor is in fact on their own. There is a set framework for the interviews with the young person, which must be conducted in a language they understand, with the help of an interpreter if needed. The child is asked to describe them self, their family and their siblings, their way of life and schooling in the home country, their life course and migration journey up to their arrival in France, and their project in France. The assessment cannot decide on a specific age but the information gathered can make up a body of evidence for the assessor to estimate whether the young person is as young as they claim to be. Assessment of minority status is also based on verifying the authenticity of any civil status documents they may have. If there is still doubt at the end of this process, the public prosecutor can order a forensic age estimation.

The clinical tests that make up a forensic age estimation are a psychological interview with a doctor, a physical examination (mainly physique on the development of secondary sexual characteristics), a dental examination, and X-rays of hand and wrist to assess bone development (the X-rays are compared with Greulich and Pyle’s benchmark Atlas, published in 1959). As a result of widespread criticism, notably questioning the reliability of these tests, the Law of 14 March 2016 lays down the conditions for their use:

“Bone X-ray tests to determine age, in the absence of valid documents and when the alleged age seems improbable, can only be performed by order of the legal authorities and on the written agreement of the person concerned. The conclusions drawn from these tests must state precisely the margin of error and are not sufficient on their own to determine whether the person is a minor. The subject has the benefit of the doubt. In the event of doubt as to the subject’s minority status, age assessment by examination of pubertal development of primary and secondary sexual characteristics is not permitted.” (Article 388 of the Code Civil)

If the young person’s minority and unaccompanied status are established within five days, the case is referred to the public prosecutor, who refers it to the national UAM unit [part of the justice ministry’s Direction de la Protection Judiciaire de la Jeunesse (DPJJ) [youth protection directorate]. The UAM unit is tasked with maintaining the placement schedule to ensure countrywide distribution of UAM. It informs the public prosecutor of the département allocated for placement of the minor, who is placed in custody by a legal “provisional placement order.” Once the placement order has been issued, the Conseil Général of the département where the minor is placed is responsible for their care.

3.2 Assessment process leaves half of unaccompanied minors with no right to protection

Under the UN Children’s Rights Convention, which France ratified in 1989, Member States undertake to provide any minor present within their territory with equal opportunities “without distinction of any kind, such as race, color, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status.”[4]

A team of French researchers recently conducted a survey[5] on the interpretation of Article 3 of the UN Children’s Rights Convention[6] in the provisions made for UAM in France (Bailleul & Senovilla-Hernández, 2016). Their study mainly covers the period before the UAM is placed in the care of the département Aide Sociale à l’Enfance, [ASE, child welfare services], i.e. from the minor’s arrival on French soil to the assessment that leads to recognition or not of minority status. The researchers made observations in the various places where UAM are found, from the street to various reception settings, and conducted interviews with professionals in the institutions and voluntary organizations and with the young people themselves. The study’s conclusions highlight a number of breaches of the UNCRC principles. The most worrying is that access to the child protection system is obstructed. Only 50% of those assessed are recognized as unaccompanied minors (DPJJ 2014). The conditions in which the assessments are conducted (in terms of the status and competence of those conducting the assessments, delays and interview and interpreting conditions) are scarcely favorable to these homeless young people. Furthermore, the factors assessed without objective foundation in the admission decisions are inappropriate. To the authors, it seems that assessment of the need for protection is being turned into an estimation of credibility and legitimacy, in a period when the rate of admission of UAM to the child welfare system is becoming an adjustment variable for the département councils. The report recommends, among other things, that “the assessment criteria be reoriented towards assessing protection needs rather than primarily focusing on estimations of age, for which formal verification seems to be a delicate matter” (Bailleul & Senovilla-Hernández 2016). Lastly, even when the youngsters are recognized as UAM, other limitations of the UNCRC are to be feared under the Law of 2016. The protocol for distributing UAM around the country takes no account of the young people’s desires as to where they want to be in care. The protocol not only means yet another move for many UAM, the youngsters may also find themselves in a place they did not want to be in, with an even stronger sense of isolation.

4 Child protection practices and care arrangements

4.1 The problem of assisting minors in situations of urgency without legal representation

Once the young person has been recognized as a UAM, they are taken into care by the département Child Protection Services. 94% of UAM are taken into care within the first year of their arrival in France (Frechon & Marquet 2016). Theoretically, they receive the same care and protection as other minors in care. However, the child protection services are tasked with “providing for all the needs of the minors in its custody and giving them guidance in collaboration with their family or legal representative.[7]

To comply with this, the situation of unaccompanied minors, who have no one in France with parental authority, would justify the involvement of a guardianship judge to appoint a guardian[8] as legal representative. Given the emergency situation that has led to them being taken into care, most UAM do not have the benefit of this measure, which is slow to set up (Helfter 2010). Only 26% of 17-year-old UAM in the ELAP study had a guardian. Age on being taken into care has an impact on this, as 37% of UAM placed in care before the age of 16 did have a guardian, compared to only 16% of those placed at age 16 or after (Frechon & Marquet 2016). This lack of a legal representative has repercussions for the quality of care. In principle, the child protection services can only take day-to-day decisions for the minor[9]; unusual decisions[10] can only be taken by the children’s judge, but the judge can only do so on an ad hoc basis[11] (Bailleul & Senovilla-Hernández, 2016). The Commission Nationale Consultative des Droits de l’Homme [national advisory committee on human rights] recommends that the guardianship system be extended to all UAM following their placement in care, making it a routine practice. As things stand, few cases are referred to the guardianship judges for this purpose (ibid., 2016).

4.2 Two priorities for the protection of UAM: a place of safety, and schooling

The residential trajectories of UAM in care are highly standardized. Most begin with a period in a children’s home before moving on to an independent structure such as a young workers’ hostel or a flat or studio flat with welfare support. Lack of places may lead the child protection services in some départements to place UAM in hotels with little or no welfare support. This is more like the shelter arrangements made for homeless adults than proper protection for minors. Also, the types of placement in which UAM are living at age 17-20 depend on their age when first taken into care. 45% of UAM in the ELAP study had arrived between the ages of 10 and 15 (28% at age 15) and 55% at age 16 or 17. Thus only 31% of UAM had lived at some point with a foster family, while 33% had lived in a hotel. Arriving later, the UAM had rarely had a smooth passage through the care system. Only 21% had lived in the same care arrangement throughout (see table 1).

At the age of 17, more than half of the UAM were living in children’s homes, 28% in independent settings (flats, hotels etc.) and only 13% with foster families, whereas a majority of non-UAM were in foster care (see table 1). More than a quarter of the UAM said they had no contact with the person tasked with their welfare follow-up. They have no other kind of supervision.

Table 1: Current care arrangements of 17-year-olds in care. Comparison between UAM and non-UAM

|

% column |

UAM |

Non-UAM |

Total |

|

Current care arrangements |

|

|

|

|

Family care |

18 |

51 |

42 |

|

Foster family |

13 |

42 |

34 |

|

Trusted third party |

0 |

4 |

3 |

|

Small specialist children’s home (lieu de vie) |

5 |

5 |

5 |

|

Residential care |

54 |

35 |

40 |

|

Independent |

28 |

13 |

17 |

|

Flat, studio flat, room |

17 |

10 |

12 |

|

Young workers’ hostel |

2 |

1 |

1 |

|

Low-grade hotel |

10 |

2 |

4 |

|

Number of different care arrangements since taken into care |

|||

|

One place |

21 |

34 |

30 |

|

Two places |

44 |

24 |

29 |

|

Three places |

25 |

18 |

20 |

|

Four places |

5 |

9 |

8 |

|

Five places or more |

4 |

15 |

12 |

|

Counselling and support |

|

|

|

|

No contact with allocated social worker |

28 |

18 |

21 |

Sources: ELAP V1, INED, 2013-14

Once placed, 94% of UAM enter the school system and, depending on their country of origin, are taught French (Lemaire, 2012) before or in parallel with their school education. At school, 73% of the 17-year-old UAM were in vocational streams: 57% CAP [certificate of professional competence], 16% BAC pro [vocational Baccalaureate]. Both these streams should lead to an apprenticeship contract, but the difficulty of finding an employer and a temporary residence permit obstructs the possibility of future integration in the world of work. Only 15% of the UAM had apprenticeship contracts.

Unlike non-UAM, who might have several sources of income (from casual jobs, an apprenticeship contract and perhaps financial help from their family), the great majority of the 17-year-old UAM were dependent on the child protection service (ASE) (81% received no money other than that given by the ASE, vs. 48% of non-UAM) while in care. 81% of UAM had no bank account (vs. 50% of non-UAM) and only 32% managed to put money aside (vs. 55%). Median income from all sources was 90€ per month; this was the same for UAM and non-UAM (Frechon et al. 2016).

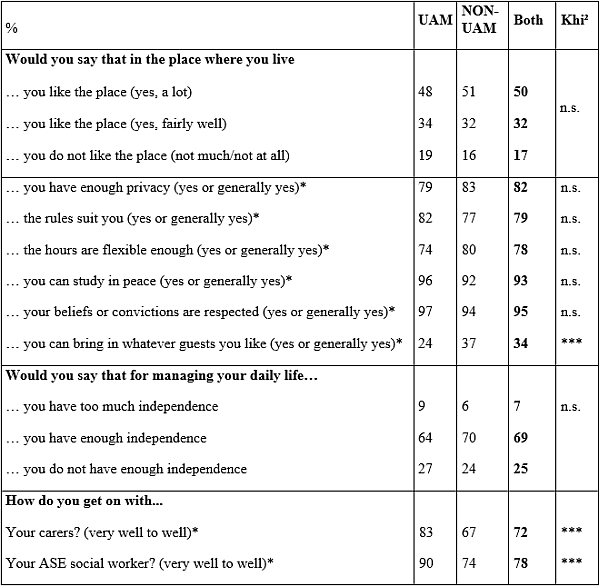

5 UAM grateful for the help provided

The ELAP study provides a lot of information on how young people in care experience their situation. 85% of the UAM considered themselves fortunate to have been put in care (vs. 73% of the non-UAM) and only 4% said they should not have been (vs. 8%); the rest answered “do not know if it is a good thing or not.” While half of the UAM like the place where they lived, 19% did not. Most UAM (and non-UAM) thought the rules suited them, that they could study in peace and that their beliefs were respected, but 27% of UAM said they did not have enough independence and more than three-quarters did not have the right to invite whoever they wanted into their care setting; this sometimes increased their sense of loneliness.

Table 2: Young people’s perceptions of their care arrangements

Significance test (Khi²) *** p<.0001 - ** p<.001 - * p<.05 – n.s = not significant

*reference population: the 17-year-olds concerned by the question.

Sources: ELAP V1, INED, 2013-2014

UAM are more likely to seek help than non-UAM; when asked “When you do not know something” 76% of UAM say that they “ask for help” (vs. 64%); 16% say they prefer to manage on their own (vs. 26%) and 8% would like to ask for help but do not know who to ask (vs. 10%). This corroborates the fact that most UAM say they “can rely on themselves” (vs. 45% of non-UAM. But when, at age 17, they are asked whether they feel ready to leave care and strike out on their own, 67% of the UAM say “not at all” (vs. 37% of non-UAM).

5.1 Extending protection beyond the age of 18: a half-hearted solution

In France, care can be extended beyond the 18th birthday. Young adults can ask for continued protection under a “young adult contract” until their 21st birthday at most. This support is conditional on the young person presenting an integration project, which usually means continuing their studies. It varies from one département to another (Capelier 2014). It is very rare for UAM not to ask for this contract, since they have no fallback solution at 18.

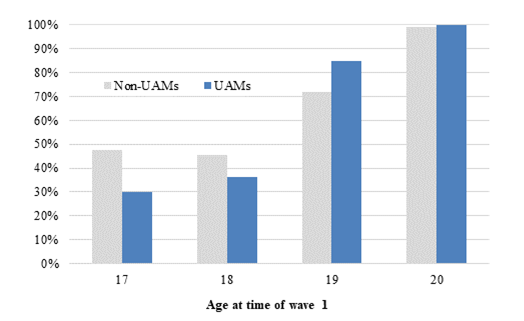

In the départements covered by the study, among 17-year-olds in care in 2013, 95% of UAM had been able to prolong protection beyond their majority by means of a young adult contract (vs. 79% on non-UAM). Eighteen months after the first survey wave, 30% of UAM had left the care system (vs. 47% of non-UAM) (Figure 3). However, UAM and non-UAM did not leave care under the same conditions. Only 28% of UAM said they had been involved in the decision to leave the care system (vs. 56% of non-UAM), and for 67% it was the ASE that decided to terminate care (vs. 38% of non-UAM). Furthermore, for UAM and non-UAM alike, the young adult contract often ends before the age of 21. Among the 19-year-olds under contract, 85% of the UAM had left welfare protection after 18 months compared to 72% of non-UAM (Figure A).

UAM do not need residence permits as long as they are minors, but at age 18 they must apply for one. The conditions for obtaining one depend on the age at which they were taken into care. On reaching their majority, a UAM taken into before the age of 16 can be issued with a temporary one-year residence permit marked “private and family life” if (a) they are enrolled in education or training and are studying seriously and consistently, (b) can provide proof that they have no links in their home country or can justify why they have not kept in touch with their family at home, and (c) the care structure attests to their integration in French society. But for those who 16 or over when taken into care, when they reach their majority each case is examined individually. In particular, if the young adult has a job contract or is still studying and they are granted a residence permit, that permit will be a temporary “student” or “employee” permit. Otherwise, each case is examined in light of exceptional considerations for admission to residency.

These conditions for obtaining a residence permit have an impact on the length of time a young person has the benefit of a young adult contract. Thus 41% of UAM who were taken into care before the age of 16 had left care 18 months later, compared to 34% who were taken into care after their 16th birthday. The Law on the protection of children and young adults makes no distinction for young adults with no residence permit.

Figure 3: Proportion of young adult UAM and non-UAM who had left care after 18 months, by age at time of first survey wave

Sources: ELAP wave 1, INED, 2013-2014

At present we know of no research on what becomes of care leavers, but the ELAP study will provide information on the situation of care leavers for a year or a maximum of 18 months after leaving. We will know what they are doing, how they are housed and any transitions to other, mainstream social services. These results will be published on the ELAP website: http://elap.site.ined.fr/fr/resultats_1/resultats/

5.2 UAM: a largely under-researched issue

In France, an association called InfoMIE pools information on the UAM issue from different sources. It has become a resource center particularly for professionals tasked with finding, hosting and supporting UAM. It publishes all news[12], documentation, research and “recommendations and proposals to try to change the current state of the law on the issue and ensure that the best interests of the child are a primary consideration as laid down in Article 3 of the UNCRC.” Most of these publications about unaccompanied foreign minors mainly concern the interpretation of the law on UAM and the gap between their rights as laid down by law and the actual care provided. Such publications have been multiplying in recent years with repeated changes in the law and the increasingly worrying situation of the migrant crisis. Despite this, very little research has been done in sociology, the educational sciences, psychology or political science. We can however mention three studies.

In 2002 sociologist Etiemble drew up a typology of UAM according to their reasons for leaving their home country. Her typology, which has long been adopted in other research on UAM in France, distinguishes the following categories:

· Exiles: minors fleeing persecution or a region at war. These are usually asylum seekers. It would be very difficult for them to go back home;

· Mandated minors: Those sent by parents or family to continue their schooling or send money to their family at home;

· Trafficked children, exploited as victims of networks dealing in prostitution, begging and other illicit activities;

· Runaways;

· Child vagrants, often minors who were already street children in their home country and who have crossed several borders in the course of their wanderings; (Etiemble, 2002)

This typology was updated in 2013, introducing two new categories:

· Minors whose goal is to find a parent or member of their extended family. When they arrive in France they do not always manage to find the person they are looking for, or that person may reject them;

· Aspirational migrants, minors who are seeking a better life and are more politicized. Their decision to come to France is a personal one, with the aim of escaping from the discrimination they have been subject to in their home country (Etiemble & Zanna 2013).

This typology has been widely adopted by professionals dealing with UAM and in all official reports on the subject. But no research has been done that would enable us to quantify the numbers of UAM in the different categories.

A team of French researchers took part in research comparing Belgium, Spain, France, Italy and Romania on the living conditions of unaccompanied minors receiving no protection in Europe. They conducted 25 interviews with minors and unaccompanied young adults who had never been taken into care or were no longer in care. In addition to this survey they conducted field observations and interviews with voluntary body professionals (other than social services) directly in contact with them. The report can be found online in French and in English[13] (Andreeva & Légaut 2013).

The question of French language classes and schooling for UAM has been studied by educationalist Lemaire. The feelings, hopes and obstacles involved in learning French and joining the school system for 33 young people aged 15 to 17, enrolled at two reception structures, was analyzed from introspective drawings the children made. The data suggest that these young people’s motivation in learning is not just instrumental, necessary for obtaining a residence permit. They see learning as a process of education and integration that they want to pursue (Lemaire 2012).

So, some research teams are well known in research on unaccompanied minors, though there are too few research projects to provide a sound knowledge of the needs and, above all, the desires of these young people, whose projects are often hampered by the complexity and difficulty of the administrative formalities they have to go through to comply with the law of the host country.

6 Conclusion

As a signatory to the UN Children’s Rights Convention, France has a duty to protect unaccompanied foreign minors, but the first difficulty such children face is to be recognized as UAM. And this problem tends to become more acute at times when migrant flows increase. The law is constantly being changed, both as regards foreigners’ rights and as regards child protection legislation, adding to the complexity of providing proper care for UAM. Reception and care for UAM under the child protection laws is perverted to better fit the legislation.

In France, where most UAM are dealt with by the child protection system and very few by the asylum-seekers’ system (8054 versus 474 in 2016), UAM reaching their majority and wishing to stay in France must either fulfil the conditions for obtaining a residence permit, or meet the criteria for obtaining French nationality. Minors entering France before the age of 16 can apply for French nationality (but will then lose their nationality of origin), or can apply for a residence permit that allows them to study or work. For this they must prove that they are unaccompanied, and that they have a project for finding employment. For young people arriving at age 16 or over it is much harder to get a residence permit, although the rules are the same. So, the welfare supports these youngsters receive is almost entirely focused on training and finding a job, at the risk of ignoring the need to treat their psychological vulnerability and of excluding all welfare support for them as “interdependent members of their community” (Goyette & Turcotte 2004). The new policy of spreading UAM around the country (the only means found to avoid overloading the child protection system in some areas) entails a major risk of leaving minors isolated from their communities. But this danger receives little consideration, since it is precisely such isolation that qualifies them for recognition as UAM – “mineurs isolés” – under the law.

References:

Andreeva M. & Légaut J.-Ph. (2013). Mineurs isolés étrangers sans protection en Europe,

recherche conduite en France dans le cadre du projet PUCAFREU. Poitiers,

France : MIGRINTER. Retrieved from maison des sciences de l’homme et de

la société : http://www.mshs.univ-poitiers.fr/migrinter/PUCAFREU/

PUCAFREU%20Rapport%20France%20FR.pdf

Bailleul C. & Senovilla-Hernández D. (2016). Dans l’intérêt de qui ? Enquête sur l’interprétation et l’application de l’article 3 de la Convention Internationale des Droits de l’Enfant dans les mesures prises à l’égard des mineurs isolés étrangers en France. Poitiers, France : MIGRINTER. Retrieved from InfoMIE : https://www.infomie.net/IMG/pdf/rapport_minas_def_version_web.pdf

Baudino, P.

(2015). Etat de santé des mineurs isolés étrangers

accueillis en Gironde entre 2011 et 2013 (Doctoral

dissertation). Bordeaux, France: Université de Bordeaux. Retrieved from : https://dumas.ccsd.

cnrs.fr/dumas-01157256/document

Capelier F. (2014) Majeurs, mais toujours isolés. Plein droit, 102(3), 26 -29.

Debré, I.,

(2010). Les mineurs isolés étrangers en France. Paris, France :

Ministère de la justice. Retrieved from MINISTRÈRE DE LA JUSTICE : http://www.justice.gouv.fr/_telechargement/

rapport_mineur_20100510.pdf

Doineau E., Godefroy J.-P., (2017). Rapport d’information fait au nom de la commission des affaires sociales sur la prise en charge des Mineurs Non Accompagnés. Paris, France : SENAT. Retrieved from : https://www.senat.fr/rap/r16-598/r16-5981.pdf

Direction de la protection judiciaire de la jeunesse (2014). Rapport d’activité du dispositif national de mise à l’abri, d’évaluation et d’orientation des mineurs isolés étrangers, 1er juin 2013- 31 mai 2014. Paris, France : DPJJ. Retrieved from : http://www.justice.gouv.fr/publication/mna/ ra_dispositif_mie.pdf

Etiemble, A. (2002). Les mineurs étrangers isolés en France. Évaluation quantitative et qualitative de la population accueillie à l’Aide sociale à l’enfance. Rennes, France: QUEST’US. Retrieved from InfoMIE : https://www.infomie.net/IMG/pdf/etude_sociologique_de_madame_etiemble.pdf

Etiemble, A., Zanna, O., (2013). Des typologies pour faire connaissance avec les mineurs isolés étrangers et mieux les accompagner. Rennes, France: TOPIK. Retrieved from InfoMIE : http://infomie.net/IMG/pdf/synthese_-_actualisation_typologie_mie_2013-2.pdf

France Terre d’Asile, (2013). France Terre d’Asile, (2013). Mineurs isolés étrangers, l’essentiel sur l’accueil et la prise en charge. Paris, France: France Terre d’Asile. http://www.france-terre-asile.org/flipbook/MIE_2015/MIE_2015.html#p=1

Frechon, I., & Marquet, L. (2016). Comment les jeunes placés à l’âge de 17 ans préparent-ils leur avenir ? (How do young people at the age of 17 prepare their futures?). Document de travail, 227, 1-9. Retrieved from INSTITUT NATIONAL D’ETUDES DÉMOGRAPHIQUES: https://www.ined.fr/fr/publications/document-travail/comment-les-jeunes-places-a-17-ans-preparent-ils-leur-avenir/

Frechon, I., Marquet L., Breugnot P., Girault C., (2016). L’accès à l’indépendance financière des jeunes placés, ELAP, Rapport remis à l’ONPE, Paris, France : INED. Retrieved from INSTITUT NATIONAL D’ÉTUDES DÉMOGRAPHIQUES : https://elap.site.ined.fr/fichier/rte/General/Minisite-Elap/independ_financ_ELAP_2016.pdf

Goyette M. & Turcotte D. (2004). La transition vers la vie adulte des jeunes qui ont vécu un placement: un défi pour les organismes de protection de la jeunesse. Service social, 51(1), 30-44.

Helfter, C. (2010). La prise en charge des mineurs isolés étrangers par l’Aide sociale à l’enfance. Une protection nécessaire et perfectible. Informations sociales, 160(4), 124-132.

Inspection générale des affaires sociales – IGAS, Inspection générale des services judiciaires – IGSJ – Inspection générale de l’administration –IGA. (2014), L’évaluation du dispositif relatif aux mineurs isolés étrangers mis en place par le protocole et la circulaire du 31 mai 2013, juillet 2014, 93 p.

InfoMIE (2014). Mineurs isolés étrangers / mineurs en danger. Retrieved from: https://infomie.net/spip.php?article652

OFPRA (2017). Rapport d’activité 2016. A l’écoute du monde. Paris,

France: Office français de protection des réfugiés et apatrides. Retrieved from : https://ofpra.gouv.fr/sites/default/files/atoms/files/

rapport_dactivite_ofpra_2016_1.pdf

Lemaire E., (2012). Portraits de mineurs isolés étrangers en territoire français: apprendre en situation de vulnérabilité. La revue internationale de l’éducation familiale, 31(1), 31 -53.

MMNA, (2017). Rapport annuel d’activité 2016, Mission Mineurs Non Accompagnés. Paris, France: Ministère de la justice. Retrieved from : http://www.justice.gouv.fr/art_pix/RAA_MMNA_2016.pdf

Ministère de la Justice, (2013). Présentation DPJJ - Les mineurs isolés étrangers: La situation en France - Données générales - Perspectives, 11 avril 2013, Paris, France : Ministère de la Justice. Retrieved from: http://infomie.net/spip.php?article666

Réseau européen des migrations, (2014). Politiques, pratiques et données statistiques sur les mineurs isolés étrangers en 2014. Paris, France: Ministère de l’Intérieur Retrieved from : http://www.immigration.interieur.gouv.fr/Europe-et-International/Le-reseau-europeen-des-migrations-REM/Les-etudes-du-REM/Politiques-pratiques-et-donnees-statistiques-sur-les-mineurs-isoles-etrangers-en-2014

Rodier C. (1986). Les enfants réfugiés d’Asie du Sud-Est: accueil et insertion. Pays-Bas, Belgique, France, Revue européenne des migrations internationales. 3(2), 49-63.

Authors’ Addresses

Isabelle Frechon

Laboratoire Printemps

– UMR 8085

47 Bd Vauban, 78047

Guyancourt cedex

isabelle.frechon@uvsq.fr

Lucy Marquet

CLERSE-UMR 8019 –

Institut de sociologie et d’anthropologie - Université de Lille 1

Bâtiment SH2, Bureau

201

Cité scientifique, 59655

Villeneuve d’Ascq

lucy.marquet@univ-lille1.fr