Unaccompanied minors in Ireland: Current Law, Policy and Practice

Samantha Arnold, Economic and Social Research Institute/European Migration Network Ireland

Muireann Ní Raghallaigh, School of Social Policy, Social Work and Social Justice, University College Dublin

Introduction

Ireland has historically been a country of emigration. Ireland became a destination country for migrants in the early 2000s. However, following the economic recession which began in 2008, immigration decreased, including for refugees and among them, UAM. Despite the recent increase in asylum flows into Ireland, the number and proportion of UAM remains low. While numbers were decreasing, care standards for UAM were improving. Ireland is therefore a particularly interesting case as the vast majority of UAM are now cared for in foster care arrangements. This paper also comes at an interesting time as new protection legislation has been introduced. In addition, despite the small numbers of UAM arriving in Ireland, a significant amount of research has been undertaken in relation to the experiences of these young people. This article draws on this research.

1.1 Data on unaccompanied minors in Ireland

Irish law does not provide a definition for UAM. However, the International Protection Act 2015 (International Protection Act) refers to persons intending to make an application for international protection who have “not attained the age of 18 years” and are not accompanied by an adult as requiring intervention from the Child and Family Agency (Tusla), the State agency with responsibility for child welfare and protection services. Tusla provide a definition for “separated children seeking asylum” rather than UAM on their website:

“children under eighteen years of age who are outside their country of origin, who have applied for asylum and are separated from their parents or their legal/customary care giver” (Tusla).

There is, however, no overarching definition for separated children or UAM generally (i.e. including those who do not apply for asylum) and there is no guidance in relation to separated children or UAM who do not seek international protection. The term UAM is used throughout this article to refer to both UAM and separated children.

The majority of UAM arrive into Ireland via Dublin Airport and Dublin (sea) Port, but other ports of entry are Shannon, Clare and Knock airports and Cork, Foynes and Rosslare sea ports (Quinn et al. 2014, p. 19). UAM who are referred to Tusla are either taken into care, reunited with family or assessed not to be under 18 and therefore referred into the system that provides support to adult asylum seekers. Sometimes UAM are taken into care initially and then reunited with family. In addition, often applications for asylum are not made immediately, meaning that a young person might be referred to Tusla in one year but not apply for asylum until the next year. These two factors suggest that caution needs to be exercised in interpreting the data.

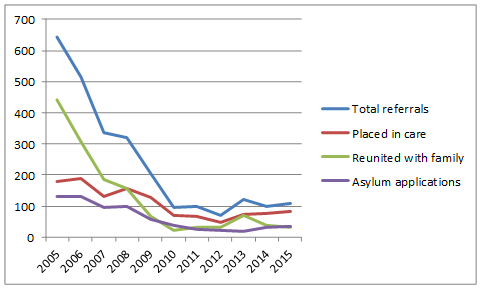

Figure 1 shows that the number of referrals to the Separated Children’s Team decreased considerably between 2005 and 2015. The total decrease during this period was 535, a decrease of 83% (from 643 to 108). Tusla attributed the decrease to the economic down turn and changes to the model of care (discussed below) and a greater focus on age determinations, which acted as “a deterrent to adults wishing to circumvent the immigration process” (Quinn et al. 2014, p.15). Furthermore, Ireland is on the periphery of Europe and as a result the current refugee crisis has had little impact on refugee and asylum flows into Ireland.

The number of UAM taken into care only decreased by 72, or 40%, during the same period (2005 - 2015). A larger proportion of UAM were taken into care in 2015 (78%) compared to 2005 (28%). This is likely due to better care provision, fewer children going missing, the greater focus on age determination (mentioned above) and a decline in the number of children reunited with family at the point of arrival. Regarding the latter, Figure 1 shows that the proportion of UAM who were reunified with family decreased from 69% in 2005 (441 of 643) to 30% in 2015 (32 of 108).

Asylum applications submitted on behalf of UAM proportionate to the number of those placed in care increased somewhat in recent years from 39% in 2010 to 40% in 2015. This represents a significant increase from the 20% recorded in 2005. This is also likely related to improvements in the provision of care, including the allocation of social workers and fewer children going missing (see Section 2).

Figure

1 Trends in Unaccompanied Minors Seeking Asylum in Ireland, 2005 - 2015

Source: Tusla Social Work Team for Separated Children Seeking Asylum, 2017; Quinn et al. 2014

Regarding more recent figures, Table 1 shows that 120 UAM aged between zero and 17 were referred to Tusla in the year 2016. Some 73 were male and 47 female. The majority were aged between 16 and 17 (50%).[1] The total number of UAM taken into care was 82. Family reunification services were provided to 42 young people. The data, which relate only to Dublin, do not indicate whether or not the children were ultimately placed in the care of family.

Table 1 Referrals of Unaccompanied Minors to Tusla in 2016

|

Male |

Female |

Total |

|

73 |

47 |

120 |

Source: Tusla Social Work Team for Unaccompanied minors Seeking Asylum

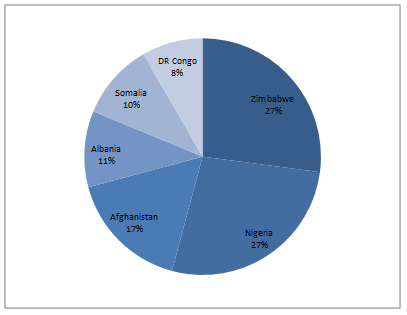

Figure 2 shows that between January 2016 and 4 August 2016, the top countries of origin of UAM referred to Tusla were Zimbabwe, Nigeria, Afghanistan, Albania, Somalia and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Figure

2 Top Countries of Origin of Unaccompanied Minors in Ireland in 2016

Source: Tusla Social Work Team for Unaccompanied Minors Seeking Asylum, 2016 NB: Year to 4 August 2016

Table 2 shows that in 2016, there were 34 applications for protection made on behalf of UAM, 5 of whom were female. The top three countries of origin of UAM who applied for asylum in 2016 were Afghanistan, Albania and Syria (Separated Children in Europe Programme 2017, p. 48).

Table 2 Applications for Refugee Protection made on behalf of Unaccompanied Minors in 2016

|

Male |

Female |

Total |

|

29 |

5 |

34 |

Source: Separated Children in Europe Programme, 2017

1.2 Characterising unaccompanied minors in Ireland

Two main discourses on UAM exist in international and Irish literature. On the one hand, UAM are characterized as vulnerable (Sourander 1998; Bean et al. 2007; Jensen et al. 2014; Martin et al. 2011). On the other hand, UAM are considered to be resilient (Smyth et al. 2015; Lustig et al. 2014). Much of the recent literature, both in Ireland and internationally, recognizes that vulnerability and resilience exist side by side (Ní Raghallaigh/Gilligan 2010; Ní Raghallaigh/Thornton 2017; Abunimah/Blower 2010).

There is a dearth of data regarding the profile of UAM in the Irish context. Existing data suggests the diversity that exists within the group. In a 2007 report, Clarke described UAM in Ireland as a heterogeneous group, which included particularly vulnerable cohorts such as minor mothers; victims of trafficking, exploitation and domestic servitude; aged-out minors (children transitioning from childhood to adulthood) and children with learning difficulties (Clarke 2007). Clarke also noted that in general Irish children in State care have experienced neglect or abuse, while this is not necessarily the case in relation to UAM. Clarke observed that some children are traumatised or exploited, while others are resourceful and resilient.

One particularly useful paper, published by Abunimah and Blower in 2010, looked at the socio-demographic profile of 100 UAM in Ireland in 2003-2004 by reviewing social work case files. Although this data is summarised here, it is important to note that the information is more than ten years old. However, it remains the only study of its kind.

Abunimah and Blower’s (2010) study drew attention to both the vulnerability and the resilience of UAM living in Ireland. It found that prior to coming to Ireland 43% of the UAM who were profiled were cared for by a parent, while 20% were cared for by another relative. Some 59% reported exposure to violence or armed conflict, while 45% reported being direct victims of violence and 32% reported being victims of sexual assault. The researchers also found high levels of mental and physical health problems in their sample: 23% were found to have acute physical health problems and 27% were described as experiencing mental health problems during their time in care. These figures suggest the vulnerability of many of the UAM living in Ireland at that time.

In terms of resilience, Abunimah and Blower found that 85% of the sample had been attending school prior to coming to Ireland (92% of boys and 78% of girls). However many reported disruption in education due to family crises and political circumstances. In relation to their time in Ireland, Abunimah and Blower found that in the 2003-2004 period 38% (of the 60 children in the sample with school records in their files) missed school regularly. The absences were attributed to anxiety and a lack of childcare for young mothers. However, it is likely that the experiences of UAM in education have improved dramatically since the provision of care was improved (discussed below). While no research equivalent to Abunimah and Blower’s study has been conducted since, several authors have referred to the importance of education in relation to UAM living in Ireland (Charles 2009, p. 44; Quinn et al. 2014, p. 57). For example, Clarke (2007) identified educational and vocational training as particularly important for this group. Similarly, in 2014, the One Foundation (a philanthropic organization) recognized the “great resilience and passion to succeed” demonstrated by many UAM and started a scholarship fund to support their third level education. Up to the end of 2013 the One Foundation supported 43 young people (the One Foundation 2014, p. 51). Although the One Foundation wound up its work in Ireland, the scholarship program has continued. The focus on the importance of education within the Irish literature is in keeping with the international literature which identifies education as a source of resilience for refugee children (Sleijpen et al. 2016; Pieloch et al. 2016).

Characterizing UAM as both vulnerable and resilient poses challenges for policy makers and practitioners. In particular, care provision needs to be able to protect children who are vulnerable whilst also ensuring it is not over-protective to the point of hindering a young person’s agency or resilience. As Bhabha (2014, p. 6) puts it, “protective policies rub up against [unaccompanied minors] autonomous desires and plans that reflect an increasing capability for self reflection and decision-making.”

2 Law and policy guiding care provision for unaccompanied minors in Ireland

Two areas of law are relevant for UAM, namely refugee law and child care law. UAM are not referred to in child care legislation, but a reference to them in the International Protection Act 2015 invokes Irish child care legislation. Section 14 of the International Protection Act provides:

(1) Where it appears to an officer referred to in section 13 that a person seeking to make an application for international protection, or who is the subject of a preliminary interview, has not attained the age of 18 years and is not accompanied by an adult who is taking responsibility for the care and protection of the person, the officer shall, as soon as practicable, notify the Child and Family Agency of that fact.

(2) After the notification referred to in subsection (1), it shall be presumed that the person concerned is a child and the Child Care Acts 1991 to 2013, the Child and Family Agency Act 2013 and other enactments relating to the care and welfare of persons who have not attained the age of 18 years shall apply accordingly” (International Protection Act 2015).

The International Protection Act therefore requires immigration officials to refer UAM to Tusla. Tusla, utilising the Child Care Act, must then determine under which arrangement to care for the child. The International Protection Act allows for Tusla to make this determination.

Although the representatives of Tusla (social workers) may choose to utilise any section of the Child Care Act, including Section 18 which involves applying for a full care order (see below), Sections 4 and 5 are most frequently used. Section 4 is typically utilised in Dublin by the Social Work Team for Separated Children Seeking Asylum (the Separated Children’s Team). The majority of UAM arriving in Ireland are referred to this team. Section 4 relates to “voluntary care.” Children are taken into care under Section 4 where they require protection and are unlikely to receive it unless they are received into care. However, Section 4(2) stipulates that the child cannot be received into its care utilizing Section 4 against the wishes of a parent or any person acting in loco parentis [in the place of a parent]. Accordingly, Tusla cannot maintain the child in its care under this section if the parent or persons acting in loco parentis wishes to resume care of the child. During such time the child is in care under this section, Tusla must have regard to the wishes of the parent or other such adult in the provision of care pursuant to Section 4(3)(b).

Section 4(4) further provides:

“where [Tusla] takes a child into its care because it appears that he is lost or that a parent having custody of him is missing or that he has been deserted or abandoned, the board shall endeavour to reunite him with that parent where this appears to the board to be in his best interests” (Child Care Act 1991).

Section 4 therefore provides an avenue through which Tusla may take a separated child into care and it provides guidance to social workers in respect of family tracing and exploring family reunification options.

Section 4 is distinct from “care orders” in two ways. Firstly, it is arguably time-limited. Section 4(3)(a) provides:

“Where a health board has taken a child into its care under this section, it shall be the duty of [Tusla]— subject to the provisions of this section, to maintain the child in its care so long as his welfare appears to the board to require it and while he remains a child” (Child Care Act 1991).

Section 4 does not allow for care beyond the age of 18. UAM aging out of the care of Tusla and transitioning to adult reception for asylum seekers (known as “direct provision”) is widely debated and criticised in Ireland (Ní Raghallaigh/Thornton 2017). While some aftercare supports are put in place, this usually happens within the “direct provision” context, thus severely limiting what can be provided especially in terms of support with accommodation, education and employment. Taking UAM into care utilising the full care order arrangements (Section 18) would allow for greater possibility of the provision of appropriate aftercare and would ensure judicial oversight of what Tusla provides.

Secondly, Section 4(3)(b) reiterates that Tusla must have regard to the wishes of the parent/guardian (see above). This is in contrast to Section 18(3)(a) “Care order,” which states that Tusla shall “have the like control over the child as if it were his parent.” The presumption is that Tusla therefore do not have legal guardianship of the UAM (Arnold/Kelly 2012). Current practice supports this contention. In order for a representative of Tusla to give permission for a medical procedure, for example, they would need to obtain permission to give consent via the court system (Quinn, et al. 2014, p. 37), if the wishes of the parent/guardian cannot be confirmed, which is usually the case in relation to UAM.

Section 5 is utilized less frequently as it is mainly relied upon in Cork, where the number of UAM referrals is much lower than Dublin (Clarke 2007, p. 6; Quinn et al. 2014, p. 19). Section 5 deals with “accommodation for homeless children.” This section sets out Tusla’s obligation to enquire into the circumstances of children who appear to be homeless. Pursuant to Section 5, Tusla must find suitable accommodation where a child is not taken into care under any section of the Act and would otherwise be homeless. Legal guardianship is not a feature of Section 5 either (Arnold/Kelly 2012). Section 5 has long been criticised by civil society as inappropriate as it does not provide adequate safeguards and opportunities for aftercare, similar to Section 4.

2.1 A change in policy towards equitable care

Prior to 2010, the care of UAM provided by the Health Service Executive (HSE) (now Tusla), was criticized because of the reliance on large scale “hostel” accommodation without 24 hour care staff and without allocated social workers. Critics argued that the high number of children going missing could be attributed to the inadequate provision of care (see Quinn et al. 2014). As a result of external and internal advocacy (from civil society and the Separated Children’s Team) an “Equity of Care“ principle was drawn up in 2008 by the Separated Children’s Team to bring the care of UAM on a par with other children in care (Quinn et al. 2014, p. 46). In 2009, the Ryan Report Implementation Plan of the Report of the Commission to Inquire into Child Abuse (Ryan Report) set out actions specific to the care of UAM, requiring: the end of the use of “separately run hostels for separated children”; the allocation of social workers to each child and the undertaking of care plans for all children in care by December 2010 (Ryan Report 2009, p. 37). Following the closure of the last hostel at the end of 2010, the equity of care principle came into practice whereby UAM were cared for in approved residential units, foster placements and supported lodgings. This is discussed in more detail below.

2.2 Suitability of mainstream child care arrangements for unaccompanied minors

Data from the Department of Children and Youth Affairs (DCYA) shows that 92% of children in the care of Tusla live in foster families. Both foster care and residential care are subject to regulations Child Care (Placement of Children in Foster Care) Regulations 1995 and Child Care (Placement of Children in Residential Care) Regulations 1995 and to inspection by the Health Information and Quality Authority (HIQA) which inspects them against the National Standards for Residential Care (Department of Health and Children 2003) and the National Standards for Foster Care (Department of Health and Children 2003). Since the implementation of the Equity of Care principle, UAM are also cared for either in residential units or in a foster home both of which are subject to the National Standards. Another form of care – supported lodgings – is also provided. This is a form of family care that involves young people having more independence and receiving less in depth support from carers. In the context of the resilience of UAM, as discussed above, this form of care is important in ensuring that young people’s sense of agency is harnessed. However, it is unclear whether the National Standards for Foster Care are also used by HIQA to inspect supported lodgings placements.

UAM do not fit seamlessly into existing mainstream care arrangements and policies. One reason for this is the disconnect between refugee legislation and child care legislation. As discussed above, the only legal provision linking UAM to child care legislation in Ireland is Section 14 of the International Protection Act. There is no additional legislation which stipulates the nature of the care to be provided to UAM. However, the fact that the International Protection Act does not prescribe the manner in which UAM are to be taken into care and merely states that the provision of the Child Care Act “shall apply,” indicates that UAM could in theory be provided with the same level of care as Irish national children. The care provision in the period leading up to 2010 illustrated that this was not the case: UAM experienced differential care from identification through to ageing-out. Recent developments as set-out above, however, indicate that this has improved considerably. Nevertheless, a number of concerns suggesting that UAM still experience differential care have been identified in the literature. As mentioned above, most of the concerns relate to utilizing Section 4 of the Child Care Act rather than a full care order (Section 18) (Arnold/Kelly 2012; Arnold/Sarsfield Collins 2011; Arnold et al. 2015). The use of Section 4 of the Child Care Act does not provide for a legal guardian or clear judicial oversight. It has been argued that when young people turn 18 their status as asylum seekers overrides their status as care leavers, as evidenced by the fact that they are accommodated in the “direct provision” system (accommodation for adult asylum seekers, see subsequent sections for more information) (Ní Raghallaigh/Thornton 2017).

As has been mentioned before, UAM are recognised as possessing both resilience and vulnerability. Regarding their resilience, these young people may often have been providers to their families in their countries of origin and may then have travelled independently across numerous countries before reaching Western Europe. In addition, they may have survived for protracted periods of time in unsafe conditions in refugee camps (European Union Committee 2016). This might pose challenges for care providers who expect them to fit into a model of care which views the child as a vulnerable dependent. As such, innovative care arrangments are often needed. Supported lodgings is an example of such an innovation but National Standards for this type of care need to be put in place so that the placements reflect the needs and best interests of the young people in question.

3 Regularizing unaccompanied minors in Ireland

3.1 Immigration procedures and international protection

Section 9 of the Immigration Act 2004, as amended requires any non-national who has been in Ireland for more than three months who is not under the age of 16 to register with the Garda National Immigration Bureau. However, in practice, UAM are often not facilitated to do so. More generally, it is rare that any avenue other than international protection is pursued for UAM. This has been met with criticism (Arnold 2013, p. 17; Arnold et al. 2015 pp. 50-53). In summary, practice in Ireland focuses almost exclusively on international protection.

In accordance with Section 15(5) of the International Protection Act, Tusla also has the responsibility to determine whether or not an application for international protection should be made on behalf of the child:

“where it appears to the Child and Family Agency, on the basis of information, including legal advice, available to it, that an application for international protection should be made on behalf of a person who has not attained the age of 18 years (in this subsection referred to as a “child”) in respect of whom the Agency is providing care and protection, it shall arrange for the appointment of an employee of the Agency or such other person as it may determine to make such an application on behalf of the child and to represent and assist the child with respect to the examination of the application” (International Protection Act 2015).

It is therefore still up to Tusla to decide whether or not to facilitate the young persons’ access to legal services. Research pre-dating the International Protection Act has argued that social workers are not equipped to make a decision of this magnitude on behalf of the child in their care (Arnold 2013) and that UAM should have the opportunity to meet and discuss their asylum and immigration options with legal professionals in their own right (Arnold et al 2015, pp. 48-50). Often UAMs’ applications for international protection are only submitted as they approach the age of 18, nearing the time that they will age out of care. This practice has been criticised (Arnold 2013, p. 17; Arnold et al. 2015, p. 50). Facilitating UAMs’ access to legal services earlier might mitigate this risk.

3.2 Resettlement and relocation

UAM are not a feature of the Irish Refugee Resettlement Programme (Arnold/Quinn 2016). The Children’s Rights Alliance (Children’s Rights Alliance 2017) reports that only four separated children were relocated to Ireland in 2016 under the Irish Refugee Protection Programme despite, despite the Minister for Justice’s commitment to prioritise the needs of UAM (Ní Raghallaigh 2016). Civil society has encouraged the Irish government to honor this commitment and to be more proactive in relocating UAM (Ní Raghallaigh 2016). The delay in relocating was generally attributed to logistical challenges and issues to be resolved on the ground in Greece and Italy in respect of security, for example (“No migration from Italy to Ireland under EU scheme” 2016). However, a successful campaign by civil society to bring children from the former Calais “Jungle” camp to Ireland, resulted in the Irish parliament passing a cross-party motion to accept up to 200 of these young people. Some of these young people began to arrive in early 2017 (Dáil Éireann Debate 2017).

4 Care of unaccompanied minors

4.1 Identification and age assessment

Although unaccompanied non-EEA minors can be refused leave to land under immigration legislation, the practice in Ireland is not to do so (Quinn et al. 2014). Thus, UAM who come to the attention of immigration officials at points of entry or who present to the International Protection Office (formerly the Office of the Refugee Application Commissioner (ORAC)) are referred to Tusla. The International Protection Act legislates for the first time on age assessment. It also provides for the possibility of utilizing medical age assessment methods while not specifying what this might include (Arnold/Castillo Goncalves 2016). Research by Quinn et al. (2014), which involved interviews with key stakeholders, including immigration officials and ORAC personnel, indicated that where there is a query about the age of a young person, the benefit of the doubt is given and young people are usually referred to Tusla who are considered better placed to undertake an age assessment. There is no statutory age assessment policy. Tusla undertakes age assessments through observations and interviews and these form part of a more general child protection risk assessment (Arnold/Castillo Goncalves 2016).

4.2 Care planning and care arrangements

After a child is referred to Tusla, a social worker from the organization will meet with him or her and begin determining his or her immediate and longer term needs. Under the Child Care (Placement of Children in Residential Care) Regulations 1995 and the Child Care (Placement of Children in Foster Care) Regulations 1995 there is a statutory duty on Tusla to institute a care planning process for children in its care (Arnold et al. 2015). This process involves a social worker utilizing a standardized care plan form which is used across Tusla child protection and welfare teams within the Irish context. The plan includes information on the reason for admission to care, the aims and objectives of the placement, the views of the child, the plan for the child in relation to health and education, the general needs of the child, and contact with family and possible family reunification. Care plans are not viewed as “a static tool” (Arnold et al. 2015, p. 14). Instead, they are seen to be in need of revision and updating as children’s needs change over time. Therefore, care planning is viewed as an ongoing process. While the care plan does not have sections relating specifically to UAM, professionals are often of the view that the document is broad and flexible enough to allow incorporation of the specific needs of UAM (Arnold et al. 2015). However, in their study on “Durable Solutions for Separated Children” Arnold et al. (2015) recommended that the form should reflect the specific needs of UAM.

The care arrangements for UAM in Ireland have vastly improved in recent years. Until 2010, young people were generally cared for in largely unsupervised hostels, although there were some exceptions to this particularly outside of the Dublin region. Hostel care provision was the subject of widespread criticism from civil society and researchers (e.g. Christie 2002; Veale et al. 2003; Mooten 2006; Ombudsman for Children 2006; Commissioner for Human Rights 2008; Corbett 2008; Charles 2009; Irish Refugee Council et al. 2011). It was criticized on the basis of being discriminatory as the care provided in these hostels was not on a par with the care provided to citizen children who were primarily either in a foster home or approved residential centers. As outlined above, this criticism, combined with the recommendations of the Ryan Report culminated in the care system for UAM being radically overhauled. Within the current system, upon arrival children over the age of 12 are initially cared for in approved residential homes that cater specifically for this client group. While in residential care the needs of the child are assessed and after a period of three to six months the majority are then transferred to foster homes or supported lodgings. Children under the age of 12 go immediately to foster homes on arrival (Ní Raghallaigh 2013).

It is important to note that there is no specific system of independent guardianship for UAM in Ireland. A guardian ad litem can be appointed where a child comes to the attention of the courts (e.g. when a care order is sought via the courts) but this rarely occurs (Arnold et al. 2014).

4.3 Young people’s experiences of care

While initially there was quite a lot of criticism of the new care arrangements (Children’s Rights Alliance 2011; Horgan et al. 2012), much of this criticism centerd around the transition period on the basis that insufficient preparation and groundwork was undertaken and as a result the transition period was a stressful one. However, the only research study that has explored the system of foster care for UAM (Ní Raghallaigh 2013), would suggest that once the new care arrangements became bedded down, people’s experiences of the system seemed quite positive. The study by Ní Raghallaigh (2013) involved interviews with UAM who had experience of living in a foster home as well as interviews with foster parents and stakeholders. Predominately, the research found that young people had positive experiences of living in a foster home. In general, positive relationships were created and young people became integrated into family life. They appreciated the efforts that carers made to make them feel welcome and included and the support that carers gave them (Ní Raghallaigh 2013). In addition, young people highlighted the importance of foster families facilitating them to be able to maintain some continuity in relation to their culture of origin and it was evident that this occurred in most of the placements, both in placements that involved cultural “matching” and in those that did not (Ní Raghallaigh/Sirriyeh 2015).

Of course, the study showed that a foster family was not without its challenges, both for the young people and for those caring for them. The study found that many of the common challenges of fostering in the general population were applicable to this client group also – for example, problems recruiting carers, problems matching carers with young people and problems of placement breakdown. However, there were also additional challenges that specifically related to the status of the young people as UAM. These included the fact that many of the young people were secretive about their past experiences thus creating a barrier to the establishment of trusting relationships. This is in keeping with the literature on UAM (Kohli 2006; Ní Raghallaigh 2014), and indeed refugees more generally (Daniel/Knudsen 1995; Hynes 2009), which frequently refers to the difficulties that forced migrants have in trusting others. In addition, the asylum determination procedure resulted in young people experiencing stress which in turn had an impact on foster placements. Finally, young people and carers alike experienced stress in relation to turning 18 because of the uncertainties that this brought.

4.4 Leaving care and after care

While Ireland’s care arrangements for UAM under the age of 18 are arguably among the best in Europe (de Ruijter de Wildt et al. 2015), the same cannot be said for the aftercare arrangements. In Ireland, aftercare is discretionary. In the case of UAM, the policy is that upon reaching the age of 18 if a young person’s asylum claim has not been finalized, young people are moved to live in the “direct provision” system. This is a system of minimal support which applies to adult asylum seekers, whereby they generally live in large institutional settings and receive meals and €19.10 per week. Those living in “direct provision” who do not have a residence permission have very limited opportunities to study and do not have a right to work. The system has received sustained criticism since its inception in 2000 on the grounds that it has no legal basis, that it infringes on people’s rights, negatively impacts on physical and mental health and has a detrimental impact on childhood, parenting and family life (Amnesty 2011; Arnold 2012; Children’s Rights Alliance 2011; Fanning/Veale 2004; Ní Raghallaigh/Foreman et al. 2016; Nwachukwu et al. 2009; Reid/Thornton 2014; Thornton 2016). Yet, despite these criticisms, national policy dictates that UAM be accommodated in “direct provision” once they turn 18 if a decision on their claim for asylum has not been reached (Health Service Executive 2011). Indeed, a recently published governmental working group report on the protection system (the McMahon report) noted the many challenges facing aged-out minors in direct provision (McMahon 2015). However, rather than recommending that aged-out minors should not be moved there, the McMahon report recommended that foster parents should be trained to build the resilience of UAM so that they can better cope with living in direct provision (Ní Raghallaigh/Thornton 2017). This highlights the tension between care and national policies in the area of asylum, which underscore the current inadequacies in aftercare arrangements for UAM in Ireland.

It should be acknowledged that social workers and aftercare workers prepare Leaving Care plans for UAM and that the young people can obtain support from an aftercare worker upon leaving care even when moving to “direct provision.” The aftercare worker links in with the child in relation to health, education, and other needs (Arnold et al. 2015). However, the impact of their work is severely curtailed by the fact that young people are living within the “direct provision” system, and without a valid residence permission, which restricts their entitlements in numerous ways, for example in terms of very limited access to education and not being permitted to work (Ní Raghallaigh/Thornton 2017). It is also curtailed by the fact that aftercare workers are often based in Dublin while their clients are living throughout the country (Ní Raghallaigh 2013). Little information is available about young people who have already received their status by the time they reach 18. The McMahon report stated that in early 2015 some 82 former UAM were receiving aftercare services, 32 of whom had some form of residence permission. It is likely that some of the 32 were still living with foster parents and that others were living independently, although data is unavailable. However, it is clear that those who have status upon reaching 18 are likely to be living in more appropriate accommodation and to be exposed to fewer risks when compared with their peers in “direct provision.” In Ní Raghallaigh’s (2013) research young people, foster parents and stakeholders all expressed concern about the impact that moving to “direct provision” would have on young people, with many worrying that the positive impact of a foster home would become “unraveled” (Ní Raghallaigh 2013, p. 80) when the move to “direct provision” occurred. In addition and as mentioned above, Ní Raghallaigh (2013) drew attention to the fact that the prospect of moving to direct provision impacts on young people even while they are still in a foster home as it creates anxiety and thus impacts on well-being and on relationships.

However, it is important to note that despite the detrimental impact of “direct provision” and not having obtained a residence permission, and the lack of evidence regarding the situation of UAM after leaving care, some evidence suggests that the resilience of some shines through despite the adversity that they continue to face. For example, with support from the One Foundation some UAM in “direct provision” were able to attend third level education, as discussed above. In addition, Ní Raghallaigh (2013) found that some young people were looking forward to turning 18 as they felt that they would have more independence when living outside of the foster care system.

5 Conclusions and future research

The provision of care to UAM in Ireland was once characterized by large institutions and high numbers of missing children and much criticism. Today, UAM in Ireland receive a high standard of care compared to those in many other countries around Europe. In the context of the European Union, where laws and policies are aimed at harmonizing asylum and immigration policies across Member States, Ireland’s system of care should be replicated and considered a minimum standard in terms of attempting to meet the diverse needs of these young people.

Policies and laws relating to UAM have come a long way in the last seven or so years. However, there is still some room to improve. Firstly, care orders (Section 18) should be used to take UAM in care to ensure the provision of a legal guardian in the State and judicial oversight of Tusla and the care planning process. Utilizing Section 18 also allows for the possibility of a guardian ad litem to be appointed. Secondly, aftercare should be improved by moving away from merely providing an aftercare worker to ensuring that young people are not moved into “direct provision,” given the detrimental impact this system is likely to have on wellbeing. Lastly, UAM should have access to legal services in their own right – Tusla should not be a gatekeeper in this regard.

Despite Ireland’s size and the relatively small number of UAM living here, a considerable amount of research on UAM has taken place, some of which has been cited above. The research has been conducted by researchers, non-governmental organizations (NGO), including the Irish Refugee Council, and the Ombudsman for Children’s Office. The topics covered have included research in relation to young people’s resilience (Ní Raghallaigh/Gilligan 2010; Ní Raghallaigh 2011; Smyth et al. 2015), the care system and guardianship (Arnold/Sarsfield Collins 2011; Charles 2009; Martin et al. 2011; Ní Raghallaigh 2013: Ní Raghallaigh/Sirriyeh 2015), durable solutions (Arnold et al. 2015), trafficking (Horgan et al. 2012; Kanics 2008) and policy (Quinn et al. 2014).

Gaps in our knowledge continue to exist, however. In particular, we know little about UAM in the asylum system. Questions remain regarding delays in submitting applications for international protection and about how UAM experience the asylum process. Due to the prominence of the issue of “getting status” as identified by UAM study participants (Arnold 2013; Arnold et al. 2015), research on outcomes of UAM cases and the challenges associated with accessing asylum procedures should be a matter of priority. While this research would fall within the legal domain, status forms part of the delivery of good care. The legal status, or lack of a legal status, of young people is identified in the research as having an impact on young people’s wellbeing and care options.

Given the arrival of UAM through the relocation program and the initiative regarding children who were previously in the Calais camp, research on their experiences of reception, of living in residential care and a foster home, and of adjusting to the education system is needed. In addition, most of the research has been cross-sectional. Longitudinal research would be beneficial, for example to see if positive experiences of a foster home lead to long term benefits for the young people. In addition, more knowledge about the integration experiences of UAM would be useful. Another area where research is needed is the area of family reunification, both in terms of the legal aspects of it as it relates to UAM, but also in terms of the impact that family reunification has on young people and on their families, especially in situations where parents have been separated from their children for years.

Several challenges face researchers in the Irish context. Given the small number of UAM living in Ireland, there is a danger of the group being over-researched with individuals being approached on numerous occasions to participate in studies. At times gatekeepers can be over-protective of the young people thus leading to researchers finding it difficult to recruit young people for their studies. An increased emphasis on meeting high ethical research standards also poses challenges, particularly as it means that more time and consideration needs to be given to the nature of the research to ensure that it meets the required standards. However, it should be emphasised that given the vulnerability of many UAM, an emphasis on conducting ethically strong research should be welcomed, despite the many complications involved (Hopkins 2008).

References:

Abunimah, A. & Blower, S. (2010). The circumstances and needs of separated children seeking asylum in Ireland. Child Care in Practice 16(2), 129-146.

Arnold, S. & Castillo Goncalves, D. (2016). The International Protection Act 2015 and Age Assessment. Irish Law Times 34(7), 94.

Arnold, S., Goeman, M. & Fournier, K. (2014). The Role of the Guardian in Determining the Best Interest of the Separated Child Seeking Asylum in Europe: A Comparative Analysis of Systems of Guardianship in Belgium, Ireland and the Netherlands. European Journal of Migration and Law 16, 467-504.

Arnold, S. & Kelly, J. (2012). Irish Child Care Law and the Role of the Health Service Executive in Safeguarding Separated Children Seeking Asylum. Irish Law Times 30, (12), 178.

Arnold, S. (2013). Implementing the Core Standards for Guardians of Separated Children in Europe: Country Report Ireland. Dublin: Irish Refugee Council.

Arnold, S., Ní Raghallaigh, M., Conaty, M., O’Keeffe, E. & Roe, N. (2015). Durable Solutions for Separated Children in Europe: National Report Ireland. Dublin: Irish Refugee Council.

Arnold S. & Sarsfield Collins, L. (2011). Closing a protection gap: National Report, 2010-11. Dublin: The Irish Refugee Council.

Bean, T.M., Eurelings-Bontekow, E., & Spinhoven, P. (2007). Course and predictors of mental health of unaccompanied refugee minors in the Netherlands: One year follow-up. Social Science & Medicine 64, 1204-1215.

Bhabha, J. (2014). Child Migration and Human Rights in a Global Age. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Charles, K. (2009). Separated children living in Ireland: A report by the Ombudsman for Children’s Office. Dublin: Office of the Ombudsman for Children.

Children’s Rights Alliance (2011). Is the government keeping its promises to children? Report Card 2011. Dublin: Children’s Rights Alliance.

Christie, A. (2002). Responses of the social work profession to unaccompanied children seeking asylum in the Republic of Ireland. European Journal of Social Work, 5, 187-198.

Clarke, M. (2007). The Equality of Care of Separated Children in Ireland: Report to The One Foundation. Retrieved 16 November 2016, from The One Foundation: http://www.issuelab.org/resource/the_equality_of_care_of_separated_children_in_ireland_report_to_the_one_foundation.

Commissioner for Human Rights (2008). Report by the Commissioner for Human Rights, Mr. Thomas Hammarberg on his visit to Ireland. Council of Europe, Brussels. Retrieved 16 November 2016, from Council of Europe: https://wcd.coe.int/ViewDoc.jsp?p=&id=1283555&direct=true.

Corbett, M. (2008). Hidden children: The story of state care for separated children. Working Note, 59, 18-24.

Dáil Éireann Debate (2017). Refugee Data. 16 February 2017 [Online]. Retrieved 12 April 2017, from Oireachtas:http://oireachtasdebates.oireachtas.ie/Debates%20Authoring/DebatesWebPack.nsf/takes/dail2017021600062#N52.

Daniel, E. V. & Knudsen, J. (Eds.) (1995). Mistrusting Refugees. London: University of California Press.

Department of Health and Children (2003) National Standards for Foster Care. Dublin: The Stationery Office.

Department of Health and Children (2003) National Standards for Residential Care. Dublin: The Stationery Office.

De Ruijter de Wildt, L., Melin, E. Ishola, P. Dolby, P. Murk, J. & van de Pol, P. (2015). Reception and Living in Families: Overview of family-based reception for unaccompanied minors in the EU member states. Utrecht, the Netherlands: Nidos, SALAR, CHTB.

Fanning, B. & Veale, A. (2004). Child Poverty as Public Policy; Direct Provision and Asylum Seeking Children in the Republic of Ireland, Childcare in Practice 10, 141-151.

Horgan, D., O’Riordan, J., Christie, A., & Martin, S. (2012). Safe care for trafficked children in Ireland: Developing a protective environment. Retrieved 16 November 2016, from Children’s Rights Alliance: http://www.childrensrights.ie/sites/default/files/submissions_reports/files/SafeCareForTraffickedChildrenInIrel and Report.pdf .

Hopkins, P. (2008). Ethical issues in research with unaccompanied asylum seeking children. Children’s Geographies, 6(1), 37-48.

Hynes, T. (2003). The Issue of ‘Trust’ and ‘Mistrust’ in Research with Refugees: Choices, Caveats and Considerations for Researchers. New Issues in Refugee Research, Working Paper No. 98. Geneva: UNHCR.

Jensen, T.K., Bjørgo Skårdalsmo, E.M. & Fjermestad, K.W. (2014) Development of mental health problems – a follow-up study of unaccompanied refugee minors. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 8, 29.

Kanics, J. (2008). Child Trafficking and Ireland. Studies: An Irish Quarterly Review, 97(388), 387-402. Retrieved 16 November 2016, from Irish Quarterly Review: http://www.jstor.org/stable/25660604.

Kohli, R. (2006a). The comfort of strangers: social work practice with unaccompanied asylum seeking children and young people in the UK. Child and Family Social Work, 11, 1-10

Kohli, R.. (2006b). The Sound of Silence: Listening to What Unaccompanied Asylum-Seeking Children Say and Do Not Say. British Journal of Social Work, 36, 707-721. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Mac Cormaic, R. (2016, September 20). No migration from Italy to Ireland under EU scheme. Retrieved 16 November 2016, from Irish Times: http://www.irishtimes.com.

Mannion, K. (2016). Child Migration Matters: Children and Young People’s Experience of Migration. Dublin: Immigrant Council of Ireland.

Martin, S., Christie, A., & O’Riordan, J. (2011). ‘Often They Fall Through the Cracks’: Separated Children in Ireland and the Role of Guardians‘. Child Abuse Review 20(5), 361-373.

McMahon Report (2015). Working Group to Report to Government on Improvements to the Protection Process, including Direct Provision and Supports to Asylum Seekers. Dublin: Department of Justice and Equality.

Mooten, N. (2006). Making Separated Children Visible: The need for a child-centred approach. Retrieved 16 November 2016, from Pobal: https://www.pobal.ie/Publications/Documents/Making%20Separated%20Children%20Visible%20-%20Irish%20Refugee%20Council%20-%202006.pdf.

Ní Raghallaigh, M. (2013). Foster Care and Supported Lodgings for Separated Asylum Seeking Young People in Ireland: The views of young people, carers and stakeholders. Dublin: HSE/Barnardos.

Ní Raghallaigh, M. & Sirriyeh A. (2015). 'The negotiation of culture in foster care placements for separated refugee and asylum seeking young people in Ireland and England', Childhood 22 (2): 263-277.

Ní Raghallaigh, M. (2016). Ireland can and should accept refugee children. Retrieved 16 November 2016, from Irish Times: http://www.irishtimes.com/opinion/ireland-can-and-should-accept-refugee-children-1.2636535.

Ní Raghallaigh, M. & Gilligan, R. (2010). Active survival in the lives of unaccompanied minors: coping strategies, resilience, and the relevance of religion. Child and Family Social Work 15 (2), 226-237.

Ní Raghallaigh, M. (2011a). Religion in the lives of unaccompanied minors: an available and compelling coping resource. British Journal of Social Work 41, 539-556.

Ní Raghallaigh, M. (2011b). Social Work with Separated Children Seeking Asylum. Irish Social Worker, Winter.

Ní Raghallaigh, M. (2011c). ‘Relationships with family, friends, and God: the experiences of unaccompanied minors living in Ireland’In M. Darmody, N. Tyrrell, & S. Song Eds.), The changing faces of Ireland: Exploring the lives of immigrant and ethnic minority children. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers, 221-236.

Ní Raghallaigh M., Foreman M. & Feeley, M. (2016). Transition: from Direct Provision to life in the community: The experiences of those who have been granted refugee status, subsidiary protection or leave to remain in Ireland. Dublin: University College Dublin and Irish Refugee Council.

Ní Raghallaigh M. & Thornton, L. (2017) Vulnerable Childhood, Vulnerable Adulthood: Direct Provision as Aftercare for Aged-Out Separated Children Seeking Asylum in Ireland, Critical Social Policy, 1-19. DOI: 10.1177/0261018317691897.

Nwachukwu, I., Browne, D. & Tobin, J. (2009). The Mental Health Service Requirements for Asylum Seekers and Refugees in Ireland. Prepared by Working Group of Faculty of Adult Psychiatry Executive Committee Retrieved 16 November 2016, from Irish Psychiatry: http://www.irishpsychiatry.ie/Libraries/External_Affairs/ASYLUM_SEEKERS_POSITION_ PAPER_191010.sflb.ashx.

Pieloch, K. A., Mc Cullough, M.B. & Marks, A.K. (2016) Resilience of children with refugee statuses: A research review. Canadian Psychology 57(4), 330-339.

Quinn, E., Joyce, C. & Gusciute, E. (2014). Policies and Practices on Unaccompanied Minors in Ireland. European Migration Network. Dublin: Economic and Social Research Institute.

Reid C & Thornton L (Eds.) (2014). Direct Provision at 14: No Place to Call Home. Dublin: Irish Refugee Council/ University College Dublin Human Rights Network.

Separated Children in Europe Programme. March 2016. Newsletter No. 46. Leiden: Defence for Children The Netherlands.

Smyth, B., Shannon M., & Dolan, P. (2015) Transcending borders: Social support and resilience, the case of separated children. Transnational Social Review 5(3), 274-295.

Sourander, A. (1998) Behavior Problems and Traumatic Events of Unaccompanied Refugee Minors. Child Abuse and Neglect 22, 719-727.

Sleijpen, M, Boeije, H.R., Kleber R.J. & Mooren T. (2016) Between power and powerlessness: a meta-ethnography of sources of resilience in young refugees, Ethnicity & Health, 21(2), 158-180.

Ombudsman for Children (2006). Report of the Ombudsman for Children to the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child on the occasion of the examination of Ireland’s second report to the Committee. Retrieved 15 November 2016, from Office of the Ombudsman for Children: https://www.oco.ie/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/OCO_AltReportUNCRC_2015.pdf.

Thornton, L (2016). ‘A View from Outside the EU Reception Acquis: Reception Rights for Asylum Seekers in Ireland’ in Minderhoud P & Zwaan K (Eds.), The recast Reception Conditions Directive: Central Themes, Problem Issues, and Implementation in Selected Member States (Oisterwijk, Wolf Legal, 2016).

Tusla. Separated Children Seeking Asylum. Retrieved 15 November 2016, from Tusla: http://www.tusla.ie/services/alternative-care/separated-children.

The Commission to Inquire into Child Abuse. (2009). Ryan Report Implementation Plan of the Report of the Commission to Inquire into Child Abuse. Retrieved 16 November 2016, from Minister for Health and Children: http://www.dcya.gov.ie/documents/publications/implementation_plan_from_ryan_commission_report.pdf (Ryan Report).

The One Foundation (2014). 2004-2013 Impact Report. Retrieved 16 November 2016, from The One Foundation: http://www.onefoundation.ie/?wpfb_dl=18.

Veale, A., Palaudaries, L. & Gibbons, C. (2003). Separated Children Seeking Asylum in Ireland. Dublin: Irish Refugee Council.

Legislation

International Protection Act 2015

Child Care Act 1991, as amended

Author’s Address:

Samantha Arnold

Economic and Social Research

Institute/European Migration Network Ireland

Whitaker Square

Sir John Rogerson’s Quay

Dublin 2, Ireland

01 863 2047

Samantha.arnold@esri.ie

Muireann Ní Raghallaigh

School of Social Policy, Social Work and

Social Justice, University College Dublin

Belfield, Dublin 2

01 716 8146

Muireann.niraghallaigh@ucd.ie

http://www.ucd.ie/research/people/socialpolicysocialworksocialjustice/drmuireannniraghallaigh/