The Accommodation and Care System for Unaccompanied Minors in Austria

Saskia Heilemann, International Organization for Migration (IOM), Country Office for Austria[1]

1 Introduction

In 2015, Austria experienced a significant increase in the number of applications for international protection,[2] i.e. more than three times as many applications as in the previous year (Bundesministerium für Inneres n.d.-a, p. 3). This increase occurred in the context of unprecedented numbers of migrants and refugees from the Middle East, South-East Asia and Africa crossing the Mediterranean for Europe (IOM n.d., p. 1), which led to strong immigration to and transit migration through Austria.

With the increase in the number of asylum applications in 2015, also the number of unaccompanied minors (UAM) applying for asylum has increased significantly (see below). This put the Austrian asylum and reception system under pressure (Koppenberg 2016, p. 17). The accommodation and care of asylum-seeking UAM became a topic discussed by the media, civil society organizations and political actors (e.g. Wiener Zeitung 2015; Die Presse 2015). Several organizational and legislative changes followed in order to adapt to the new situation, some of which were necessary to transpose EU directives into national law. In the following article, these developments are presented, while providing an overview of the accommodation and care system for UAM in Austria and an insight into UAMs’ living situation. Thereby, the focus of the article lies on UAM who are within the basic welfare support system of Austria. This group contains (i) UAM who have applied for asylum and whose asylum procedure is still pending, (ii) UAM who have been granted subsidiary protection status, and (iii) UAM who have been granted asylum no longer than four months ago. It has to be noted that for all other UAM, i.e. those who do not receive basic welfare support, a different system applies, namely that of the Kinder- und Jugendhilfe [Children and Youth Service]. In practice, every UAM applying for asylum in Austria falls under the system of basic welfare support providing for the basic needs of the minor. The Children and Youth Service is complementing this support by providing additional care and education measures. If the UAM becomes ineligible for basic welfare support, e.g. when the minor is granted asylum status, then the system of the Children and Youth Service takes over together with the Bedarfsorientierte Mindestsicherung [Needs-based Guaranteed Minimum Resources] (Ganner et al. 2016, pp. 22-23, 29, 38). Covering both systems would go beyond the scope of this article.[3] Instead, the article will concentrate on the accommodation and care provided to UAM in the Austrian basic welfare support system, focusing on the legal framework and the accommodation and care arrangements. Available statistical data and research will be presented and any gaps highlighted.

This article is based on various sources such as legislative texts, policy documents, research reports, journal articles, media and press releases, and internet sources. Statistical information is provided based on available data from Eurostat in order to allow the reader to compare the situation in Austria with that in other EU Member States. I used data from nation-wide studies where no data from Eurostat was available. Furthermore, the article builds upon the study “Unaccompanied Minors in Austria – Legislation, Practices and Statistics”, which was carried out in 2014 in the framework of the European Migration Network (EMN).

2 Definition of “unaccompanied minor” and available data

In Austria, the term “unaccompanied minor” (UAM) is defined in the Niederlassungs- und Aufenthaltsgesetz [Settlement and Residence Act] as a foreign national minor who is not accompanied by an adult person who is accountable for the minor by law (Art. 2 para 1 subpara 17 Settlement and Residence Act). Concerning the definition of who is an underage person, the Allgemeines Bürgerliches Gesetzbuch [General Civil Code] considers – in line with the Convention on the Rights of the Child – a person who has not reached the age of 18 to be a minor (Art. 21 para 2 General Civil Code). This definition reflects those used by relevant international stakeholders (Koppenberg 2014, p. 24).

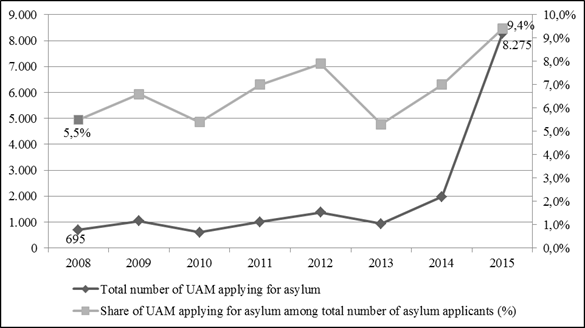

According to experiences from Non-Governmental Organizations (NGO) and authorities, UAM who come to Austria mostly apply for asylum (Koppenberg 2014a, p. 46). This is reflected by the available statistics, which show that 8,275 UAM applied for asylum in 2015 (see Figure 1). In comparison, only 11 UAM received a “Red-White-Red Card plus” according to Art. 41a para 10 subpara 1 Settlement and Residence Act – a settlement permit that is explicitly available to UAM[4] (Bundesministerium für Inneres n.d.-b, p. 28).

Since 2008 – this is the earliest year for which data is available from Eurostat – the number of UAM applying for asylum in Austria has increased significantly. Between 2008 and 2014 the number fluctuated between a minimum of 600 and a maximum of 1,975 persons. In 2015, however, there had been a significant increase of asylum applications lodged by UAM. While in 2014 there were 1,975 UAM applying for asylum, in 2015 Austria received a total of 8,275 asylum applications from UAM, which is more than four times as many. Also, the share of UAM applying for asylum among the total number of asylum applicants has increased over the period 2008 to 2015 (see Figure 1). In 2008, 5.5% of all asylum applicants were UAM, while the percentage in 2015 was 9.4. In between, however, the share varied (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Unaccompanied Minors Applying for Asylum in Austria, Total and Share (2008-2015)

Source: Eurostat 2016a and 2016b; own calculation.

Of the 8,275 UAM applying for asylum in Austria in 2015, 95% were male and 91% were 14 years or older (Eurostat 2016c, p. 2). Looking back seven years, it becomes clear that this situation has not changed or not changed significantly – in 2008, 86% were male and 91% were 14 years or older (Eurostat 2016b). The main country of origin in 2015 was by far Afghanistan with 5,610 UAM seeking asylum in Austria, representing 68% of all UAM applying for asylum that year (Eurostat 2016c, p. 4). Seven years before, in 2008, the main country of origin was already Afghanistan, but with only 31% of all asylum-seeking UAM (Eurostat 2016b).

Overall, in 2015, Austria was one of the EU Member States that received the highest number of UAM applying for asylum. With 9.5% of all asylum-seeking UAM registered in the EU Member States, Austria ranked fourth, right after Sweden, Germany and Hungary (Eurostat 2016c, p. 2).

It has to be noted that these statistics represent the number of UAM who applied for asylum in Austria but not the number of UAM currently residing in Austria. Such data is not available. What is known, however, is that not all UAM who apply for asylum in Austria actually stay in the country (Koppenberg 2014a, pp. 77-78). According to the available data, 1,566 UAM absconded during their asylum procedure in Austria in 2015 (Bundesministerium für Inneres 2016a, p. 1). For obvious reasons, there is no reliable information available on where these minors went. Some might have continued their migration journey toward northern EU Member States along with other refugees who transited through Austria during the migration movements that Europe experienced in 2015 (see above). However, there are worries that others might have become victims of human trafficking (Missing Children Europe 2016). In fact, a study ordered by the European Commission identifies the categories of “child victims of war, crisis or (natural) disaster” and “children subject to migration planned by their families,” as two of seven risk categories. These define groups of children that are specifically at risk of becoming victims of child trafficking. As an analysis of 84 cases of child trafficking in EU Member States showed, children that were sent abroad by their families became exploited in 29% of all cases (i.e. 24 out of the 84 cases analyzed). War, crisis or (natural) disaster led to child exploitation in 5% of the cases (i.e. four out of 84 cases) (Cancedda et al. 2015, p. 69).

3 Legal framework

A division of competencies characterizes the legislation on UAM in Austria. Notably, the legislative competence is shared between the federal government and the provinces. This is typical for Austria as a federal state and applies to various political areas such as – for example – education, child welfare and social welfare.

When UAM in Austria apply for asylum, they are treated under the asylum portfolio. Therewith, Austria is one of only a few EU Member States that does not apply a similar reception system to all UAM but differentiates according to the residence status (EMN 2015, p. 23). With regard to accommodation and care arrangements the most important Austrian legal document is the Grundversorgungsvereinbarung (Basic Welfare Support Agreement), which defines the kind of reception conditions and maximum allowances to be provided for asylum seekers and other target groups of the agreement, including UAM. Special reception conditions for UAM are outlined in Art. 7. Art. 9 sets specific maximum amounts to cover the reception and care conditions. These provisions are transposed into the Grundversorgungsgesetz – Bund [Federal Basic Welfare Support Act] and respective provincial laws.

Info Box no. 1: Guardianship Provisions for Unaccompanied Minors in Austria

|

In Austria, the guardianship for UAM is regulated separately from the asylum or basic welfare support legislation. Instead, the respective provisions can be found in the General Civil Code. The courts have to appoint a Kinder- und Jugendhilfeträger [Children and Youth Service Authority] as the minor’s guardian if a legal guardian is needed and no other suitable person (e.g. relative) can be found (Art. 209 General Civil Code). The guardianship has to be taken by the Children and Youth Service Authority of the province in which the minor has his/her usual residence (i.e. normally residence of at least six months) or – if this is not applicable – has his/her residence (Art. 212 General Civil Code). The Austrian Oberster Gerichtshof [Supreme Court] clarified in its decision on 19 October 2005 that also UAM enjoying basic welfare support are to be appointed a legal guardian. The Court explained that basic welfare support could not replace guardianship. Furthermore, The Court clarified that guardianship provisions as stipulated in the General Civil Code do not differentiate between Austrian citizens and foreigners (Oberster Gerichtshof, 19 October 2005, 7Ob209/05v). Regarding their responsibilities, legal guardians always have to consider and ensure the best interest of the child (Art. 138 General Civil Code). More precisely, the legal guardians’ duties include care and education, asset management and legal representation of the minor (Art. 160-169 General Civil Code). In practice, the Children and Youth Service Authorities do not always exercise guardianship duties directly. With regard to care and education, the guardian usually assigns tasks to the reception facility where the UAM is accommodated (Koppenberg, 2014a, p. 37). The legal representation in asylum and alien law proceedings is normally outsourced to law firms or Non-Governmental Organizations (NGO) (Fronek/Rothkappel 2013, p. 17). The legal representation with regard to administrative authorities, schools, nurseries, medical and psychological treatment, conclusion of vocational training agreements, etc. is in most cases outsourced (Koppenberg 2014a, p. 37). One particularity regarding guardianship concerns the first phase of the asylum procedure during which Austria’s responsibility to assess the application for international protection is clarified, i.e. the admission procedure. During that time, the legal advisor of the UAM is also the legal representative before the Bundesamt für Fremdenwesen und Asyl [Federal Office for Asylum and Immigration] and the Bundesverwaltungsgericht [Federal Administrative Court]. Thereby, Austria complies with the provisions defined in Art. 25 of the recast Asylum Procedures Directive (2013/33/EU). After admission to the asylum procedure and allocation to a reception facility of the provinces, the Children and Youth Service Authorities take over the legal representation of the UAM in these matters (Art. 10 para 3 and para 6 Bundesamt für Fremdenwesen und Asyl-Verfahrensgesetz [Federal Office for Immigration and Asylum Procedures Act]). Consequently, experiences from practice show that UAM in admission procedure have a legal representative through their legal advisor but are not always appointed a guardian (Fronek/Rothkappel 2013, p. 16). This means in practice that legal representation in matters other than the asylum procedure and other guardianship duties are not ensured during the admission procedure (Szymanski 2016, p. 19). |

On the occasion of the 25th anniversary of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child on 20 November 2014, the situation of UAM in Austria was closely examined. One of the points of discussion was that in Austria, UAM are primarily considered as asylum seekers or refugees and only secondly as children (Asylkoordination Österreich 2014). The Volksanwaltschaft [Ombudsman Board] requested in this regard that one must not differentiate between Austrian children and children seeking asylum – e.g. that the maximum amounts of basic welfare support shall be increased and adapted to the cost rates of the Children and Youth Service (Volksanwaltschaft 2015). In 2015, an additional factor occurred. Due to the strong increase in the number of asylum applicants, the Austrian reception system was under constraint (Koppenberg 2016, p. 17). Consequently, there was a lack of adequate reception facilities in the provinces and UAM had to stay for extended periods in the initial reception facilities of the federal state. This unsatisfactory situation led to renewed demands to increase the daily allowance of basic welfare support for UAM (UMF – Arbeitsgruppe unbegleitete minderjährige Flüchtlinge n.d) and to ensure that the rights of UAM are met in line with the UN Convention (Don Bosco Flüchtlingswerk Austria n.d.-a).

At the end of the year, in December 2015, legislative changes were introduced, which increased the financial allowances for accommodation and care. Through a change of the Basic Welfare Support Agreement, selected maximum payments for various basic welfare support measures as set forth in Art. 9 of the Basic Welfare Support Agreement were increased, including the daily amounts for UAM. The maximum amount for rent, food and care per person and day was increased by EUR 20 for UAM living in apartment-sharing groups (totaling EUR 95), by EUR 3.50 for those living in residential homes (totaling EUR 63.50), and by EUR 3.50 for those in supervised accommodation or in other accommodation (totaling EUR 40.50) (Art. 2 Vereinbarung über eine Erhöhung ausgewählter Kostenhöchstsätze [Agreement on an Increase of Selected Maximum Amounts]). It has to be noted, however, that these are the maximum amounts up to which the expenses of the provinces are settled by the federal government.[5] The actual amounts provided for basic welfare support may be lower and differ from province to province (Glawischnig 2015, p. 25).

4 Accommodation and care arrangements

4.1 Responsibilities and arrangements

The responsibility for the accommodation and care of UAM is shared between the federal government and the provinces. The federal state (i.e. the Bundesministerium für Inneres [Federal Ministry of the Interior]) is mainly responsible for asylum-seeking UAM in admission procedures (Art. 3 para 1 Basic Welfare Support Agreement). The provinces (i.e. the provincial authorities) are responsible for providing basic welfare support to UAM during the actual asylum procedure as well as to those who were granted subsidiary protection or asylum no longer than four months ago (Art. 4 para 1 Basic Welfare Support Agreement).

Accordingly, two different stages can be distinguished with regard to the accommodation and care of UAM. Asylum-seeking UAM who are in the admission procedure are accommodated in reception facilities of the federal state. When they have been admitted to the actual asylum procedure the responsibility for accommodation and care passes over to the provinces (Federal Ministry of the Interior n.d.-c).

The geographical distribution is decided by the federal state in agreement with the provinces according to quotas that are in proportion to the provinces’ population (Art. 1 para 4 Basic Welfare Support Agreement). In addition, UAM are allocated to reception facilities according to some other criteria. As for reception facilities of the federal state, in the framework of the Fremdenrechtsänderungsgesetz 2015 [Act Amending the Aliens Law 2015] and in order to transpose Art. 22 para 1 of the recast Reception Directive (2013/33/EU) into Austrian law it was included in Art. 2 para 1 Federal Basic Welfare Support Act that any special needs are taken into account to the greatest possible extent. In compliance with Art. 21 of the recast Reception Directive (2013/33/EU),[6] Art. 2 para 2 Federal Basic Welfare Support Act states that family relationships, ethnic particularities and the special needs of vulnerable persons are required to be taken into account when assigning individuals to reception facilities. Since 1 October 2015 UAM are transferred from the initial reception facilities of the federal state to so-called special reception facilities (UMF – Arbeitsgruppe unbegleitete minderjährige Flüchtlinge n.d.-b). As of September 2016 there were 11 such facilities in five provinces (Bundesministerium für Inneres n.d.-d). The UAM stay in these facilities until they are allocated to reception facilities of the provinces (Asylkoordination Österreich n.d.). In the provinces, there are three different categories of reception facilities available to which UAM are allocated according to the degree of care and supervision that they need. These are (i) apartment-sharing groups for minors with a particularly high need of supervision which provide a supervision rate of 1:10 (one staff per 10 UAM), (ii) residential homes for minors who are unable to care for themselves with a supervision rate of 1:15, and (iii) supervised accommodation for minors who are able to care for themselves if supervised, providing a supervision rate of 1:20 (Art. 7 para 2 Basic Welfare Support Agreement).

The federal government and the provinces can outsource the provision of basic welfare support (Art. 3 para 5 and Art. 4 para 2 Basic Welfare Support Agreement). The federal government has contracted a company, ORS Service GmbH, while the majority of provinces have outsourced the basic welfare support for UAM to other NGO including church-based organizations (Koppenberg 2014a, pp. 51-52).

The basic welfare support for UAM includes – as laid down in Art. 9 of the Basic Welfare Support Agreement – various benefits which are available to all beneficiaries. Most importantly it includes accommodation, food, health insurance, clothing, pocket money, school supplies and commuting expenses for pupils as well as information, counseling, and social support.

In addition, the Basic Welfare Support Agreement provides for special benefits for UAM. Primarily, this includes care and supervision according to the rates mentioned above. Care and supervision are provided by the staff working in the reception facilities (Koppenberg 2014a, p. 55) and include information, counseling and social support (Art. 9 Basic Welfare Support Agreement). If necessary, socio-pedagogical care and psychological support must be provided (Art. 7 para 1 Basic Welfare Support Agreement). Furthermore, the care of UAM comprises

· an adequately structured daily routine (e.g. through education, leisure activities or sports);

· the clarification of questions with regard to age, identity, origin and the residence of family members;

· the clarification of future perspectives;

· if relevant, the facilitation of family reunification; and

· the development of an integration plan and preparation measures with regard to schooling, vocational training and employment (Art. 7 para 3 Basic Welfare Support Agreement).

In addition, German language courses are provided at an extent of 200 teaching units per UAM (Art. 9 Basic Welfare Support Agreement).[7]

Info Box no. 2: Support Measures for Unaccompanied Minors Provided by Non-Governmental Organizations in Austria

|

In Austria, numerous Non-Governmental Organizations (NGO) including civil society organizations, private associations and church-affiliated organizations provide various support measures for UAM in several provinces of Austria that go beyond the level of accommodation and care provided for by law. Here are some examples: · The project “Bildungswege – ausbildungsbezogene Perspektiven für unbegleitete junge Flüchtlinge“ [“Paths to Education – Training Perspectives for Unaccompanied Young Refugees”] supports UAM and other young refugees in finding an apprenticeship. Thereby, the association Lobby.16, which runs the project, works closely together with private enterprises. The support ranges from skills training courses and vocational orientation to counselling and mentoring (Lobby.16 n.d.). · “PROSA – Projekt Schule für Alle” [“PROSA – School for Everyone Project”] provides classes in basic education and other schooling for UAM with a special focus on asylum-seeking UAM who do not fall under the compulsory schooling anymore and therefore do not have access to regular schools. PROSA is a project of the Bildungsinitiative Österreich [Initiative for Education Austria] (PROSA n.d.). · The project “Connecting People” is implemented by the NGO Asylkoordination Österreich [Asylum Coordination Austria] and brings together (former) UAM who seek asylum or are already granted asylum status with Austrian sponsors who support them in their integration, e.g. through leisure activities, educational support or handling of administrative procedures (Connecting People n.d.). · The project “CulTrain – Cultural Orientation Trainings for Young Refugees” – implemented by the International Organization for Migration (IOM) Country Office for Austria – provides orientation for (former) UAM with regard to legal, cultural and other aspects of daily life in Austria. The project furthermore conducts intercultural events in cooperation with Austrian youth organizations to facilitate the exchange between the (former) UAM and Austrian youth (IOM Country Office for Austria n.d.). · The project “Moses” provides counselling and support for former UAM, for example with regard to daily life, administrative matters, education, apprenticeships and employment as well as accommodation. It is implemented by the church-affiliated organization Don Bosco Flüchtlingswerk Austria [Don Bosco Refugee Facility Austria] (Don Bosco Flüchtlingswerk Austria n.d.-b). |

Overall, almost all UAM who receive basic welfare support are accommodated in reception facilities as described above (Koppenberg 2014a, pp. 51-52). Most of them fall into the category of “apartment-sharers,” where they are provided with a supervision rate of 1:10 (Glawischnig 2015, p. 23). However, accommodation is also possible in other suitable organized reception facilities as well as in individual accommodation (Art. 7 para 1 Basic Welfare Support Agreement). In addition, asylum-seeking UAM below the age of 14 are in some provinces accommodated in reception facilities of the Children and Youth Service (see for example Land Oberösterreich n.d.). Foster families can also host UAM but this option had been rarely used – until recently (Glawischnig 2016a, pp. 28-29). In comparison, accommodating asylum-seeking UAM in foster families is common in the majority of EU Member States (EMN 2015, p. 23).

The significant increase in the number of UAM applying for asylum in 2015 had direct impact on the accommodation and care situation. The lack of adequate reception facilities and the willingness of individuals to accommodate UAM in their homes led to a change in policy (Glawischnig 2016a, pp. 28-29). Since summer 2015, various efforts were made in all of Austria’s provinces to provide UAM with the possibility to live in foster families instead of reception facilities. The provincial governments started to promote this type of accommodation through measures and programs such as info sheets, information events or specific trainings for potential foster parents (see for example Land Tirol n.d.; Land Oberösterreich n.d.; Wien.at n.d.). The Kinder- und Jugendanwaltschaften Österreichs [Ombudsmen for Children and Youth in Austria] organized a meeting to coordinate these initiatives and to facilitate a harmonized approach throughout Austria (Kinder- und Jugendanwaltschaften Österreichs 2016). As of September 2016, of the around 6,000 UAM living in Austria at that time, 150 were living in foster families (K. Glawischnig, personal communication, September 2019, 2016).

4.2 Data and experiences of unaccompanied minors

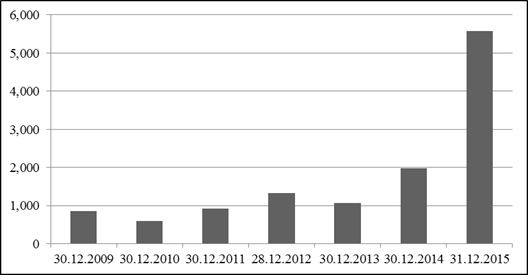

The number of UAM who receive basic welfare support has varied over the past seven years, i.e. the years for which data is available. The trend of UAM receiving basic welfare support reflects the changing number of asylum applications lodged by UAM (see Figure 1 and 2). Between 2009 and 2014 the number fluctuated between a minimum of 593 and a maximum of 1,948. In 2015, however, there was a significant increase. While on 30 December 2014, 1,984 UAM received basic welfare support, the number had risen to 5,576 on 31 December 2015. That is at the end of 2015, there were almost three times as many UAM receiving basic welfare support in Austria than one year before (see Figure 2). The growing number of UAM seeking asylum in Austria can explain this increase (see Figure 1).

Figure 2: Number of Unaccompanied Minors Receiving Basic Welfare Support in Austria (2009-2015)

Source: Bundesministerium für Inneres 2015, p. 2; Bundesministerium für Inneres 2016b, p. 1; Koppenberg 2014, p. 54.

Important data on how UAM experience care arrangements in reception facilities comes from an explorative study carried out in 2015 by the Institute for Empirical Social Studies (IFES) on behalf of the Österreichische Bundesjugendvertretung [Austrian Youth Representation]. The study is based on a survey carried out among 66 (former) UAM residing in the Austrian provinces of Burgenland, Lower Austria, Upper Austria, and Vienna. The (former) UAM who became interviewed were between 13 and 22 years old. The majority of them arrived in Austria in 2015 (62%). The interviews were carried out between November and December 2015. The questionnaire focused on the social living conditions and covered in particular the areas of accommodation, education, daily structure, and financial resources. Some of the main findings are summarized below:

· The majority (35%) of the interviewees were living in initial reception facilities. An almost equal share (32%) was living in specialized reception facilities for UAM. Overall, the latter facilities were better equipped in terms of furniture and other amenities according to the interviewees. In particular, initial reception facilities were lacking computers, internet access, television, and kitchen facilities while emergency accommodation was not providing computers and supplies for leisure activities. In the initial reception facilities, 48% of the UAM shared a room with eight or more persons while the number of roommates in other reception facilities was smaller.

· The majority of interviewed UAM (55%) did not visit school, served any apprenticeships or were involved into other kinds of training. However, 53% were attending German language classes and 18% had already completed one.

· One third of the UAM structured their day and activities through school, others through apprenticeship, training or German language classes. Those who were not involved in any educational program suffered from a lack of structure.

· With regards to their financial resources, over 60% of the UAM said that they had EUR 40 or less per month at their disposal. This means that many of them could not afford basic items including sanitary products, communicative devices such as smartphones and internet or social activities such as sports (Hochwarter/Zeglovits 2016).

As mentioned above, only since summer 2015, more and more UAM have been living in foster families. Hence, so far not much information is available on how UAM and their foster families experience these care arrangements. Public and media debate first and foremost focused on promoting the new accommodation and care concept and on finding potential foster families. First discrepancies manifested when potential foster parents were looking for a girl or a baby, while the majority of UAM in Austria are boys who are 14 years or older (Der Standard 2015). First experiences collected and published by the NGO Asylkoordination Österreich reveal the following challenges and advantages of accommodating UAM in foster families:

· Language is a challenge in the communication between the UAM and the foster family. In combination with the cultural differences, the lack of a common language leads to misunderstandings.

· An advantage is that UAM build trust in their foster parents. Trust, together with a secure and stable family environment, helps UAM to alleviate psychological stress caused by the situation of their family back in the country of origin or the uncertain outcome of their asylum procedure in Austria.

From these first experiences, Asylkoordination Österreich concludes that accommodating UAM in foster families facilitates a faster and better integration due to the security and safety provided by the family and because the supervision ratio allows to better respond to the UAMs’ needs (Glawischnig 2016a, pp. 32-35). According to the NGO, accommodating UAM in foster families is positive not least because of a lack of adequate reception facilities in 2015/beginning of 2016 (Der Standard 2015).

4.3 Ending of accommodation and care arrangements

In terms of accommodation and care arrangements, the point at which UAM turn 18 years of age becomes a turning point. When turning 18, UAM who receive basic welfare support have to move to organized reception facilities for adults or individual accommodation. They are no longer entitled to the higher, UAM-specific maximum amounts for basic welfare support, to UAM-specific reception conditions or to other special benefits. There are no specific provisions to support UAM in advance of the transition. However, on an individual basis, the guardian and/or the staff of the reception facility inform the UAM about the upcoming changes and provide support (Koppenberg 2014a, pp. 74-75). This situation seems to be typical for EU Member States where in general former UAM need to change accommodation and only in some states measures are in place to provide support to UAM in advance (EMN 2015, pp. 33-34).

The transition period is challenging for the UAM.[8] Overall, the transition starts for UAM when turning 18 which is at an earlier age than youth in general and also with less social support and personal capabilities. According to Rothkappel, the challenge for UAM is to arrange daily life themselves and in a new environment after relocation to a reception facility for adults that does not provide the same level of support and counselling (Rothkappel 2014, p. 42). For UAM who were staying with siblings who are still minors, relocation means that they now have to live separate from each other. Also, if UAM are relocated to a reception facility in another municipality or province, they have to interrupt schooling or vocational training and their social networks (Koppenberg 2014a, pp. 75-76). This interruption and the loosing of bond to the former social workers or guardian impact on UAM’s psychological state (Rothkappel 2014, p. 44; UNHCR & COE 2014, p. 28). The transition is all the more challenging as UAM are often still processing their flight experiences, are worried about their family and relatives, and are uncertain about the outcome of their asylum procedure (Rothkappel 2014, pp. 31, 42). According to Rothkappel, the lack of information about the changes that come along with turning 18 and the insufficient preparation lead to insecurity, worries, and fear amongst other reactions (Rothkappel 2014, pp. 31, 33).

However, some good practice examples exist where NGO provide tailored support and information and/or specific accommodation to UAM who turned 18. For example, some NGO provide detailed information and support with regard to the transition to adulthood, notably with finding alternative accommodation. In some cases, former UAM can stay in their reception facilities for a limited period of time (e.g. until they graduate from school) if places are available. For example, the majority of the 25 accommodation facilities researched by Rothkappel (2014) offer some kind of post-care accommodation. The main precondition is that the necessary financial means, e.g. through basic welfare support or other means of the respective organization running the facility, are available. The type of post-care accommodation and the support offered to former UAM differ greatly (Rothkappel 2014, pp. 58-67; UNHCR & COE 2014, p. 28).

5 Research overview and remaining gaps

In Austria, the NGO Asylkoordination Österreich is particularly active when it comes to UAM. The NGO mainly supports the networking and exchange between practitioners throughout Austria such as those working in reception facilities, staff of Children and Youth Service Authorities, and organizations providing various support services to UAM. It also engages in media work and general lobbying for UAM. With regard to research, Asylkoordination Österreich published some general works providing an overview of UAM-related topics, including a publication on challenges for separated children (Asylkoordination Österreich et al. 2010). According to that study, the most significant challenges for UAM in Austria relate, for example, to upholding the best interest of the child, inadequate long-term solutions, securing guardianship, transition when turning 18, and family reunification. The NGO also conducts assessments of pressing issues such as guardianship. In their assessment Fronek & Rothkappel (2013) come to the conclusion that the Austrian legislation is “quite favorable” in securing the best interest of the child and providing guardianship. However, when it comes to implementing legislation and ensuring thorough guardianship there is room for improvement (Fronek/Rothkappel 2013, pp. 40-42; see also Info Box no. 1). In addition, Asylkoordination Österreich regularly publishes articles in its journal Asyl Aktuell that provide an analysis of the current situation and challenges. One article form 2016, for example, stressed the need to expand the intensive care and individual support available to UAM with specific needs, e.g. for those who suffer from traumatization and show psychiatric conditions (Glawischnig 2016b). Finally, Asylkoordination Österreich researches and publishes UAM’s experiences in Austria, for example in the article Real Life Experiences between Support and Uncertainty (Glawischnig, 2016c).

Other stakeholders conducting research on UAM in Austria include the International Organization for Migration (IOM), which conducted country reports providing a comprehensive overview of UAM-related topics such as asylum procedure, age assessment, guardianship, care and accommodation, education, vocational training, integration support, and turning 18. The reports cover all aspects from a legal, policy, and practical angle. The country reports were conducted within various countries, allowing for comparison and sharing of best practices. Findings from the most recent report of this kind by Koppenberg (2014) are cited throughout this article. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) carried out country comparisons on specific aspects such as turning 18. Some of the results are presented in subsection 4.3. Also, a few legal analyses were published in scientific journals looking into UAM in the Austrian asylum procedure and the question of age assessment. Lukits & Lukits (2013), for example, explain the legal aspects of medical age assessment in asylum procedures. UAM are also a popular topic among students. Various Bachelor and Master Theses – some including small-scale primary research such as interviews with UAM – have been carried out by students of Austrian universities. One example is the Master Thesis by Rothkappel (2014) on UAM in transition to adulthood in Austria. Some of the findings are reflected in subsection 4.3. In 2015, primary research carried out by the Institute for Empirical Social Studies (IFES) on behalf of the Österreichische Bundesjugendvertretung provided important empirical data on how UAM experience care and reception arrangements (see section 4.2).

Further research is needed on two aspects particularly. Firstly, and as this article shows, almost no information and statistics are available on the living situation of UAM, i.e. on the question of how they experience their accommodation and care arrangements. In addition, no research could be identified on the social situation of UAM compared to other groups of young people. Therefore, questions such as what characterizes UAM in comparison with their same-age peers born in Austria in terms of education or health cannot be answered. Secondly, post-monitoring would be needed in order to follow the life courses of UAM after they have left the basic welfare support system or the post-care accommodation provided by NGO. This would allow to understand how UAM fare e.g. one, three or five years later and to draw conclusions on the quality of the available care and accommodation arrangements as far as the preparation of UAM for a self-sufficient life goes. Such research and statistics would allow on the one hand evaluating the accommodation and care provisions for UAM and other measures, and on the other to understand the integration potential and challenges of this particular group. According to the Expertenrat für Integration [Expert Council for Integration], such research is not only needed for asylum-seeking UAM but the group of refugees as a whole (Expertenrat für Integration 2016, p. 77).

One challenge to researching UAMs’ situation in Austria and filling these gaps is a lack of publicly available administrative data and the non-availability of databases for sampling processes. For example, in Austria integration indicators have been developed in order to evaluate the various dimensions of the integration process (language and education, employment and unemployment, health and social issues, security, living conditions and segregation, types of family, naturalizations, and subjective views) on an annual basis. In terms of groups of migrants, the published data, however, only disaggregates by migration background and citizenship. Therefore, based on these integration indicators, it is not possible to say how UAM fare compared to other groups of migrants (Statistics Austria 2016). A second example is the Integrierte Fremdenapplikation [Integrated Alien Application] which includes both data on persons who applied for asylum or for residence permits and persons who hold a valid residence permit or have a valid residence status. However, this database system does not include a personal code and is not linked to other administrative databases such as the Hauptverband der österreichischen Sozialversicherungsträger [Main Association of Austrian Social Insurance Institutions] or the Zentrale Melderegister [Central Register of Residents] (Expertenrat für Integration 2016, pp. 76-77). Therefore, no data is available, for example, on the social situation. Also the sampling for carrying out primary research becomes a challenge when there is no database containing combined information such as address and residence status. This is a general challenge for all asylum-related data and does not only apply to UAM. This lack of publicly available administrative data is, however, partly compensated by qualitative data or non-representative data produced by various research studies (see, for example, Hochwarter/Zeglovits 2016; Rothkappel 2014).

6 Conclusions

In 2015, a strain on the Austrian reception system for asylum seekers in general and for asylum-seeking UAM in particular evolved due to the significant increase in asylum applications in the context of an unprecedented number of migrants and refugees crossing the Mediterranean for Europe. In response, as the article outlined, several organizational and legislative changes were introduced with regard to accommodation and care:

· The financial allowances for accommodation and care for UAM were increased.

· It was legally stipulated that any (possible) special needs are assessed upon admission to basic welfare support and subsequently taken into account to the greatest possible extent.

· It was further stipulated that the special needs of vulnerable persons are to be taken into account when assigning such individuals to reception facilities.

· Special reception facilities were set up where UAM are accommodated before being allocated to their final housing in the provinces.

· Measures and programs were set up to promote the accommodation of UAM in foster families.

These changes were also spurred by discussions about differences in the treatment of asylum-seeking UAM and other minors in need, by the necessity to transpose EU regulations into national law, and by the willingness of individuals to accommodate UAM in their private homes.

The information available proved to be sufficient to understand the Austrian reception system for UAM (i.e. the legal provisions, organizational structure, and practices). However, the article found that there is a lack of publicly available administrative data and primary research on

· the living situation of UAM and how they experience the accommodation and care arrangements;

· the social situation of UAM compared to other groups; and

· the UAM’s situation after they left the accommodation and care arrangements or post-care accommodation.

Just as for other refugees, this research and data would be necessary in order to evaluate the accommodation and care provisions and to understand the integration potential and challenges of UAM in Austria. In order to enable researchers to provide such information, some remaining gaps in publishing and/or collecting administrative data and linking of administrative databases must be addressed.

References

Allgemeines Bürgerliches Gesetzbuch [General Civil Code], JGS No. 946/1811, in the version of FLG I No. 43/2016.

Asylkoordination Österreich et al. (2010). Challenges for Separated Children in Austria, Denmark, Poland, Slovakia and Slovenia. Retrieved April 2017, from: www.asyl.at/adincludes/dld.php?datei=180.02.ma,bisc_compilation_report.pdf.

Asylkoordination Österreich (2014). Agenda Asyl kritisiert Betreuung von minderjährigen Flüchtlingen – ‘Ein Bett allein ist zu wenig’. Press Release, 7 October 2014. Retrieved August 2016, from: www.asyl.at/fakten_2/betr_2014_06.htm.

Asylkoordination Österreich (n.d.). Das Asylverfahren seit 2015. Retrieved September 2016, from: http://umf.asyl.at/files/ASYLVERFAHREN2016.pdf.

Bundesamt für Fremdenwesen und Asyl-Verfahrensgesetz [Federal Office for Immigration and Asylum Procedures Act], FLG I No. 87/2012, in the version of FLG I No. 25/2016.

Bundesministerium für Inneres [Federal Ministry of the Interior] (2015). Reply to the Parliamentary Request No. 3341/J (XXV.GP) of 15 December 2014 regarding “die in Grundversorgung befindlichen Fremden 2014” (3180/AB of 13 February 2015). Retrieved September 2016, from: www.parlament.gv.at/PAKT/VHG/XXV/AB/AB_03180/imfname_384186.pdf.

Bundesministerium für Inneres [Federal Ministry of the Interior] (2016a). Reply to the Parliamentary Request No. 9051/J (XXV.GP) of 19 April 2016 regarding “vermisste unbegleitete Minderjährige” (8635/AB of 7 June 2016). Retrieved September 2016, from: www.parlament.gv.at/PAKT/VHG/XXV/AB/AB_08635/imfname_539685.pdf.

Bundesministerium für Inneres [Federal Ministry of the Interior] (2016b). Reply to the Parliamentary Request No. 7508/J (XXV.GP) of 21 December 2015 regarding “die in Grundversorgung befindlichen Fremden 2015” (7156/AB of 19 February 2016). Retrieved September 2016, from: www.parlament.gv.at/PAKT/VHG/XXV/AB/AB_07256/imfname_506851.pdf.

Bundesministerium für Inneres [Federal Ministry of the Interior] (n.d.-a). Asylstatistik 2015. Retreived August 2016, from: www.bmi.gv.at/cms/BMI_Asylwesen/statistik/files/Asyl_Jahresstatistik_2015.pdf.

Bundesministerium für Inneres [Federal Ministry of the Interior] (n.d.-b). Niederlassungs- und Aufenthaltsstatistik – Dezember 2015. Retrieved July 2016, from: www.bmi.gv.at/cms/BMI_Niederlassung/statistiken/files/2015/Niederlassungs_und_Aufenthaltsstatistik_Dezember_2015.pdf.

Bundesministerium für Inneres [Federal Ministry of the Interior] (n.d.-c). Unterbringung und Betreuung. Retrieved August 2016, from: www.bmi.gv.at/cms/BMI_Asyl_Betreuung/unterbringung/start.aspx.

Bundesministerium für Inneres [Federal Ministry of the Interior] (n.d.-d). Asylwesen. Behörden. Retrieved September 2016, from: http://www.bmi.gv.at/cms/BMI_Asylwesen/behoerden/start.aspx.

Cancedda, A., et al. (2015). Study on high-risk groups for trafficking in human beings. Final report. Luxembourg: European Commission. Retrieved September 2016, from: www.ecpat.at/fileadmin/download/Studien/study_on_children_as_high_risk_groups_of_trafficking_in_human_beings_0.pdf.

Connecting People (n.d.). Patenschaften für unbegleitete Minderjährige und junge erwachsene Flüchtlinge. Retrieved September 2016, from: www.connectingpeople.at/index.htm.

Convention on the Rights of the Child, A/RES/44/25, 20 November 1989, United Nations Treaty Series vol. 1577.

Der Standard (2015). Zuspruch und Probleme bei Pflegeeltern-Suche für Flüchtlinge. 24 November 2015. Retrieved April 2017, from: http://derstandard.at/2000026284613/Zuspruch-und-Probleme-bei-Pflegeeltern-Suche-fuer-Fluechtlinge.

Die Presse (2015). Länder beschließen Quote für unbegleitete Minderjährige. 6 May 2015. Retrieved October 2016, from: http://diepresse.com/home/politik/innenpolitik/4724858/Laender-beschliessen-Quote-fur-unbegleitete-Minderjaehrige.

Directive 2013/33/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 26 June 2013 laying down standards for the reception of applicants for international protection (recast), 29 June 2013, OJ L 180/96.

Don Bosco Flüchtlingswerk Austria (n.d.-a). Keine halben Kinder – Kinderrechte sind unteilbar! Retrieved August 2016: www.keinehalbenkinder.at/.

Don Bosco Flüchtlingswerk Austria (n.d.-b). Nachbetreuung Moses. Retrieved September 2016, from: www.fluechtlingswerk.at/so-helfen-wir-den-jugendlichen/nachbetreuung-moses.

European Migration Network (EMN) (2014). Asylum and Migration Glossary 3.0. Luxembourg: European Commission. Retrieved January 2017, from: www.emn.at/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/emn-glossary-en-version.pdf.

European Migration Network (EMN) (2015). Policies, practices and data on unaccompanied minors in the EU Member States and Norway. Brussels: European Commission. Retrieved April 2017, from: www.emn.at/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/emn_study_unaccompanied_minors_synthesis_report_final_eu_2015.pdf.

Eurostat (2016a). Asylum and first time asylum applicants by citizenship, age and sex Annual aggregated data (rounded), [migr_asyappctza]. Retrieved August 2016, from: http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-datasets/-/migr_asyappctza.

Eurostat (2016b). Asylum applicants considered to be unaccompanied minors by citizenship, age and sex Annual data (rounded), [migr_asyunaa]. Retrieved August 2016, from: http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-datasets/-/migr_asyunaa.

Eurostat (2016c). Almost 90 000 unaccompanied minors among asylum seekers registered in the EU in 2015. Press Release 87/2016, 2 May 2016. Retrieved August 2016, from: http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/2995521/7244677/3-02052016-AP-EN.pdf/19cfd8d1-330b-4080-8ff3-72ac7b7b67f6.

Expertenrat für Integration [Expert Council for Integration] (2016). Integrationsbericht 2016: Integration von Asylberechtigten und subsidiär Schutzberechtigten in Österreich – Wo stehen wir heute? Zwischenbilanz des Expertenrats zum 50 Punkte-Plan. Retrieved September 2016, from: www.bmeia.gv.at/fileadmin/user_upload/Zentrale/Integration/Integrationsbericht_2016/Integrationsbericht_2016_WEB.pdf.

Fremdenrechtsänderungsgesetz 2015 [Act Amending the Aliens Law 2015], FLG I No. 70/2015.

Fronek, H., & Rothkappel, M.-T. (2013). Implementing the Core Standards for guardians of separated children in Europe – Country Assessment: Austria. Vienna: Asylkoordination Österreich. Retrieved September 2016, from: www.corestandardsforguardians.com/images/23/327.pdf.

Ganner, M. et al. (2016). Gutachten zu Rechtsproblemen von SOS-Kinderdorf – Österreich mit unbegleiteten minderjährigen Flüchtlingen. Retrieved January 2017, from: www.sos-kinderdorf.at/getmedia/62987502-9d66-4629-8679-9b811351d943/Gutachten-SOS-Kinderdorf-Mindestsicherung.pdf.

Glawischnig, K. (2015). Krise ohne Ende. Asyl Aktuell 4/2015, 22-27. Retrieved April 2017, from: www.asyl.at/adincludes/dld.php?datei=180.15.ma,erhoehter_betreuungsbedarf_bei_umf.pdf.

Glawischnig, K. (2016a). Ein Flüchtlingskind in die Familie aufnehmen. Asyl Aktuell 1/2016, 28-35. Retrieved April 2017, from: www.asyl.at/adincludes/dld.php?datei=180.14.ma,gasteltern_glawischnig.pdf.

Glawischnig, K. (2016b). Erhöhter Betreuungsbedarf bei UMF. Asyl Aktuell 3/2016, 28-31. Retrieved April 2017, from: www.asyl.at/adincludes/dld.php?datei=180.12.ma,erhoehter_betreuungsbedarf_bei_umf.pdf.

Glawischnig, K. (2016c). Unbegleitete minderjährige Flüchtlinge – Lebensrealität zwischen Unterstützung und Unsicherheiten. In Österreichische Liga für Kinder- und Jugendgesundheit (Ed.), Bericht zur Lage der Kinder- und Jugendgesundheit in Österreich 2016 (pp. 71-75). Vienna: Österreichische Liga für Kinder- und Jugendgesundheit. Retrieved April 2017, from: www.asyl.at/adincludes/dld.php?datei=180.13.ma,liga_jb16_last_web_2.pdf.

Grundversorgungsgesetz – Bund [Federal Basic Welfare Support Act], FLG I No. 405/1991, in the version of FLG I No. 70/2015.

Grundversorgungsvereinbarung [Basic Welfare Support Agreement], FLG I No. 80/2004.

Hochwarter, C., & Zeglovits, E. (2016). Unbegleitete minderjährige Flüchtlinge in Österreich. Forschungsbericht im Auftrag der Österreichischen Bundesjugendvertretung. Vienna: IFES. Retrieved September 2016, from: www.bjv.at/cms/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/pk-material-aktualisiert_10-02-161.pdf.

International Organization for Migration (IOM) (n.d.). Mixed Migration Flows in the Mediterranean and Beyond – Compilation of available Data and Information, Reporting Period 2015. Retrieved August 2016, from: http://doe.iom.int/docs/Flows%20Compilation%202015%20Overview.pdf.

International Organization for Migration (IOM) Country Office for Austria (n.d.). CulTrain - Cultural Trainings for Young Refugees. Retrieved September 2016: www.iomvienna.at/en/cultrain-cultural-trainings-young-refugees.

Kinder- und Jugendanwaltschaften Österreichs (2016). Fachtagung Patenschaften und Gastfamilien: Flüchtlingskinder brauchen individuelle Begleitung. Press Release, 30 May 2016. Retrieved August 2016, from: www.kija.at/files/30.05.2016_Fachtagung-Salzburg-Patenschaften-und-Gastfamilien.pdf.

Koppenberg, S. (2014a). Unaccompanied Minors in Austria – Legislation, Practices and Statistics. Vienna: IOM. Retrieved April 2017, from: www.emn.at/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/EMN_UAM-Study2014_AT_EMN_NCP_eng.pdf.

Koppenberg, S. (2014b). The Organization of the Reception System in Austria. Vienna: IOM. Retrieved April 2017, from: www.emn.at/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/Organization-of-Reception-Facilities_EN_final.pdf.

Koppenberg, S. (2016). Austria – Annual Policy Report 2015. Vienna: IOM. Retrieved August 2016, from: www.emn.at/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/Annual-Policy-Report-Austria-3.pdf.

Land Oberösterreich [Province of Upper Austria] (n.d.). Aufnahme von minderjährigen Flüchtlingen bzw. unbegleiteten minderjährigen Fremden (UMF) in die eigene Familie – Informationsblatt für Interessierte. Retrieved September 2016, from: www.kinder-jugendhilfe-ooe.at/Mediendateien/dl_Pflege_UMF.pdf.

Land Tirol [Province of Tyrol] (n.d.). Ehrenamtliche Mitarbeit im Bereich der unbegleiteten minderjährigen Flüchtlinge (umF). Retrieved September 2016, from: www.tirol.gv.at/gesellschaft-soziales/kinder-jugendhilfe/bereichunbegleiteteminderj/.

Lobby.16 (n.d.). Unser Kernprojekt: Bildungswege – ausbildungsbezogene Perspektiven für unbegleitete junge Flüchtlinge. Retrieved September 2016, from: www.lobby16.org/projekte.htm.

Lukits, D., & Lukits R. (2013). Die medizinische Altersuntersuchung im österreichischen Asylrecht. Zeitschrift für Ehe- und Familienrecht EF-Z 2013/129, 196-201.

Matti, E. (2016). Studie zur Situation besonders vulnerabler Schutzsuchender im österreichischen Asyl- und Grundversorgungsrecht. Retrieved September 2016, from Vienna: Amnesty International Österreich: www.amnesty.at/de/view/files/download/showDownload/?tool=12&feld=download&sprach_connect=433.

Missing Children Europe (2016). Europol confirms the disappearance of 10,000 migrant children in Europe. Retrieved September 2016, from: http://missingchildreneurope.eu/news/Post/1023/Europol-confirms-the-disappearance-of-10-000-migrant-children-in-Europe.

Niederlassungs- und Aufenthaltsgesetz [Settlement and Residence Act], FLG I No. 100/2005, in the version of FLG I No. 122/2015.

Oberster Gerichtshof [Supreme Court], 19 October 2005, 7Ob209/05v.

PROSA (n.d.). Projekt Schule für Alle. Retrieved September 2016: www.prosa-schule.org/.

Rothkappel, M.-T. (2014). “Adult over Night?” Separated Young People in Transition to Adulthood in Austria. Master Thesis, University of Vienna. Retrieved August 2016, from: http://othes.univie.ac.at/35709/1/2014-07-29_0600885.pdf.

Statistics Austria (2016). Migration & Integration. Figures, Data, Indicators 2016. Retrieved September 2016, from: www.bmeia.gv.at/fileadmin/user_upload/Zentrale/Integration/Integrationsbericht_2016/20160906_Z-Card_Englisch_web.pdf.

Szymanski, W. (2016). Und das Hamsterrad dreht sich ... (Teil II). Zum Fremdenrechtsänderungsgesetz 2015. migraLex 1/2016, 18-20.

UMF – Arbeitsgruppe unbegleitete minderjährige Flüchtlinge (n.d.-a). Februar 2015: 740 UMF befinden sich in der Bundesbetreuung. Retrieved August 2016, from: http://umf.asyl.at/aktuell/.

UMF – Arbeitsgruppe unbegleitete minderjährige Flüchtlinge (n.d.-b). Sonderbetreuungsstellen ab 1. Oktober 2015. Retrieved August 2016, from: http://umf.asyl.at/aktuell/.

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), & Council of Europe (COE) (2014). Unaccompanied and Separated Asylum-Seeking and Refugee Children Turning Eighteen: What to Celebrate? Strasbourg: UNHCR/COE. Retrieved August 2016, from: www.coe.int/t/dg4/youth/Source/Resources/Documents/2014_UNHCR_and_Council_of_Europe_Report_Transition_Adulthood.pdf.

Vereinbarung zwischen dem Bund und den Ländern gemäß Artikel 15a B-VG über eine Erhöhung ausgewählter Kostenhöchstsätze des Art. 9 der Grundversorgungsvereinbarung [Agreement between the Federal Government and the Provinces Pursuant to Article 15a of the Federal Constitutional Act, Concerning an Increase of Selected Maximum Amounts Laid Down in Art. 9 of the Basis Welfare Support Agreement], FLG I No. 48/2016.

Volksanwaltschaft [Ombudsman Board] (2015). Serie Kinderrechte: Mangelnde Betreuung von unbegleiteten Minderjährigen Flüchtlingen. Press Release, 23 February 2015. Retrieved August 2016, from: http://volksanwaltschaft.gv.at/artikel/serie-kinderrechte-mangelnde-betreuung-von-unbegleiteten-minderjaehrigen-fluechtlingen.

Wien.at (n.d.). Pflege- und Gasteltern für Unbegleitete minderjährige Flüchtlinge gesucht. Retrieved September 2016: www.wien.gv.at/menschen/magelf/adoption/pflege-gasteltern-umf.html.

Wiener Zeitung (2015). Kritik an Unterbringung von minderjährigen Flüchtlingen. 19 February 2015. Retrieved August 2016, from: www.wienerzeitung.at/nachrichten/oesterreich/politik/736010_Kritik-an-Unterbringung-vonminderjaehrigen-Fluechtlingen.html.

Author´s

Address:

Saskia Heilemann

International Organization for Migration (IOM), Country Office for Austria

sheilemann@iom.int

www.iomvienna.at