The Sociological Imagination of Meals on Wheels: How a Home Delivered Meal Program Sheds Light onto Larger Social Issues.

Zachary Hozid, Vermont Law School

David Fazzino, Bloomsburg University of Pennsylvania, Department of Anthropology

1 Introduction:

On January 30, 2014, Zach Hozid (ZH) gave a short presentation to the Alaska Mental Health Trust (AMHT). This was a part of the Alaska Commission on Aging’s (state agency) presentation to the AMHT advocating for money for various senior services in the state. ZH’s presentation was solely on the Juneau Meals on Wheels (MOW) program, which ZH had been coordinating for nearly two years. The presentation to AMHT underscored the need to better understand how these services provide, or have the potential to provide, more than their stated offering. The data shows that MOW improves the health of recipients (Sirey et al, 2008; Frongillo and Wolfe, 2010), but there is little research on the social impact of MOW on the lives of seniors. In addition, there is very little research that assesses the daily life of seniors receiving MOW. The current research attempts to address such holes in the literature.

The Alaska Commission on Aging was seeking funding support from the AMHT because government financial support for senior services are not keeping up with costs. The government has not always been responsible for senior services. It was not until the passage of the Older Americans Act in 1972 that the US federal government began funding senior services, including MOW. However, in the last decade or so, funding has not kept pace with increasing costs and demand for services. Thus, senior service organizations in the US that have come to rely on government support are now seeking additional funding.

Rarely do service organizations make efforts to qualitatively improve services. Most efforts to attain funding are instead to maintain the current level of service, or to try and keep up with growing demand for material assistance. This is the current trend among most social services, not just senior services, in the United States (Farquhar et al, 2007; Katz and Key, 2014). These trends have reduced the ability of many social service organizations to provide adequate services. In addition, salaries and benefits in the social services have been reduced or remained stagnant with little opportunity for advancement. This has created bureaucratization and limited professionalism in the work force and, along with budget stagnation and reduction, has led to stagnation in the realms of creative and innovative programming and overall advocacy efforts on behalf the organization’s “client”[1] population. Hence, it is rather unsurprising that few attempts have been made to qualitatively improve senior services. As will be demonstrated, the MOW program in fact offers, with some imaginative planning and development, a gateway and potential to provide such higher level of services that could also coordinate with other community programs and organizations.

The current study aims to get a better understanding of what the MOW service actually means in terms of services and outreach and what impact it has on the lives of those receiving the meals. The results presented here can then be used to assess how this program, and similarly situated programs, can be improved. The results illuminate the lives and needs of MOW clients.

This paper also provides a framework that other service organizations can use to assess their own programs. We refer to this framework as the Social Service Sociological Imagination. This framework is derived from C. Wright Mills’ Sociological Imagination (Mills, 1959). The sociological imagination is a way of understanding the world. As Mills points out “[n]either the life of an individual nor the history of a society can be understood without understanding both.” (Mills, 1959; 3). Thus, the possessor of the sociological imagination is capable of situating the individual’s daily experience within the larger context of society and understanding social structures within its historical development (Mills, 1959).

In our Social Service Sociological Imagination, the social service organization takes the place of the individual. In other words, a service organization that possesses the Social Service Sociological Imagination can situate its daily interactions and services within the larger social and historical context and understand the development of historical trends. Ultimately this enables the organization to understand the role that they play in the lives of their target population, and how the service impacts and shapes the community.

There are numerous benefits for a service organization to possess such awareness. Most importantly in the day-to-day interactions, the organization can adapt its services to best meet the ever-changing needs of those they serve. The organization needs to be agile enough to directly interpret client issues through synergies delivered more reflexively. The organization should understand not just their role in the lives of those they serve, but what other organizations serve the same population. This understanding can lead to more collaboration between service providers. On a larger social impact level, service organizations possessing this imagination can play an active role in informing policy makers of the needs of the population.

Social service organizations, such as MOW, regularly work directly with people in need, which places them in a prime position to assess how current social structures are marginalizing certain populations and what can be done to ensure the health and well-being of those people. It is through the development and application of the Social Service Sociological Imagination that service organizations can learn how to improve services and how best to advocate for those in need.

While realizing the unique positioning of those in service organizations to better understand the day-to-day challenges facing those they serve, we must also be aware of the ethical issues that potentially arise in conducting research on such a population, albeit with the best of intentions to improve services. From an ethical perspective, caution must be exercised to realize the power imbalances between those providing services and those receiving services in the context of any research program. Certainly, those working in Service organizations may have built rapport over long periods of time with those whom they serve, but care must be taken to navigate any continuing imbalances. In the case of this research, the University of Alaska Fairbank’s Institutional Review Board reviewed the research protocol and procedures for informed consent were established.

ZH has worked for four different social service organizations; none of them employed a Social Service Sociological Imagination. Yet, all could have benefited from doing so because the level of service provided was, at best, only a temporary solution to long-term issues with little interest in developing a holistic understanding. These organizations operated in a top-down fashion with directives from above dictating how goods and services were to be provided. Little interest was ever shown in trying to understand the experiences of clients or grasping the larger social picture and using that as the driving force in developing services.

The paper draws from experience with the Juneau MOW program from 2012-2014, as well as research conducted from August 2013-June 2014 to come to a better understanding of MOW, its impact on client’s lives, and how the service can be improved. This paper also highlights how, with proper planning, service organizations can more effectively understand the interface of service delivery and client expectations and frustrations. Towards this end, the research instruments used for data collection have been included as appendices (see Appendices 1-3). Similar studies conducted in other organizations should modify these research instruments, as appropriate, depending on the relationships between Service organizations and intended recipients.

2 Juneau Meals on Wheels:

MOW in Juneau, Alaska, is operated by Catholic Community Services (CCS) as part of their senior Nutrition and Transportation Services. The stated goal of CCS’s senior services is to "promote the health, independence and quality of life of seniors in Southeast Alaska through the delivery of quality services and the development of community resources” (CCS senior services mission statement, 2013). The nutrition program is designed to provide a supplementary meal source for seniors, rather than as the primary source of nutrition. The Juneau Senior Nutrition Program’s main offering is a lunch service provided Mondays through Fridays. The meals are standardized and comprised of: a salad, half a cup of vegetables, three ounces of meat or fish, one serving of grains, and milk. Lunches are served at the senior center, the Bridge Adult Daycare, MOW and two days a week a meal is served at a church on Douglas Island (located about three miles from the senior center). All the meals are prepared at the senior center. In total, about 150 meals are made each week day, around 90 of which are for MOW, with the remaining 60 going to the other locations mentioned above.

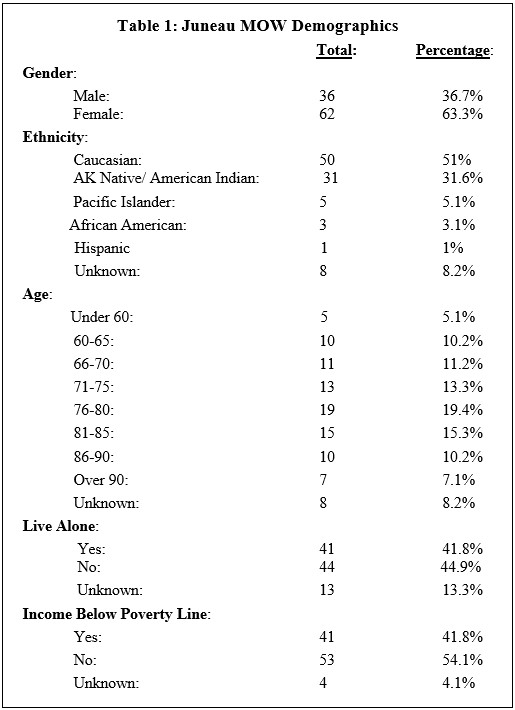

The Juneau MOW program has 98 registered clients (see Table 1 for demographic information on MOW clients); although about ten of them temporarily suspended the service for various reasons, such as being out of town or in the hospital. The median age of MOW recipients is 75 with a range between 45 and 95 years old. Funding for meals of those under 60 comes from Medicaid. Some clients have been receiving meals for over eight years, but the median length of time receiving MOW is around six months. The average rate of growth from month-to-month of the MOW program from January 2012 to April 2014 was approximately one client per month, although there was a drop in client numbers during some months.

MOW is provided to seniors over the age of 60 who are unable to provide for themselves and unable to come to the senior center for lunch. Most of the MOW recipients are homebound to the extent that they only leave their home for medical appointments. Since most MOW recipients are homebound, and many live alone (40%), it is unsurprising that they tend to have little social contact. Of those living alone, some do have caregivers that regularly come to their home to provide assistance. Financial stress is also an issue for many MOW recipients. Based on monthly income alone, 41.8% of MOW recipients are below the Alaska poverty line (see table 1). Of those that live alone, about 61% are below the poverty line. Thus we must also consider that isolation and poverty can intensify mobility and health burdens for seniors.

3 Situating Seniors in a Neoliberal Era:

In this section we situate seniors and senior services in light of broader national and global concerns. By doing so we highlight the relative importance of the MOW in the context of broader societal concerns. Specifically, we review relevant literature, to situate MOW within a broader cultural, social, economic, and political milieu, with emphasis on: aging, neoliberal processes, food security, and other existing programs and organizations.

Lamb (2014) discusses the North American notion of “active” or “successful” aging by pointing out that there is no one clear definition of “successful aging”, but the key themes are: maintaining productivity, independence, agency in the aging process, and agelessness. In short, the basic idea is that as one ages, one’s capacity to “stay young and healthy” as well as physically and mentally competent, remains at high levels (Lamb 2014). In addition, one is expected to maintain control of their health. This concept is born out of the biomedical model of health that is widely used in Americans society. The biomedical model (and successful aging model) is individualistic, placing an onus on an individual rather than considering the social determinants of health. Liang and Luo (2012) suggest that this model of aging is part of a consumer and materialist culture. Lamb (2014) argues that “successful aging” sets people up for failure since it is increasingly unattainable with aging and decreasing functionality.

The “successful aging” model marginalizes and undervalues seniors in society (Corner et al, 2006). This model of aging stresses that seniors distance themselves from all the stereotypes of aging, and remain active citizens in society. If they fail to do so there is little room in society for them. Hay (2010) argues that individuals in the United States must suffer through and endure pain in order to remain productive and hence valuable members of society.

Services, such as MOW, exist to keep seniors alive and healthy, but they do not address issues of isolation. Social services, such as senior centers and adult day care centers, often connect seniors with other seniors, but they rarely connect seniors with other “productive” segments of society. An exception to this is Befrienders Program wherein young people from the community volunteer to visit with and assist seniors on a daily basis reducing feeling of isolation experienced by seniors (Bullock and Osborne 1999). The Befrienders Program is an example of a program that not only provides material services to seniors, but also develops social networks in the community (Bullock and Osborne 1999).

Seniors receiving MOW are especially dependent on senior aid programs. As food production systems become more constrained due to economic and environmental changes, the health and wellbeing of seniors becomes more at risk. The rise of neoliberal capitalism, which is characterized by an increase in privatization and diminished role of the State in order to promote “efficient” production, is an influencing factor of how social services are run (Hasenfeld and Garrow, 2012; Woolford and Curran, 2013). The privatization and industrialization of food production and distribution has also been pivotal in shifting the historical relationships between food and community. The global food system delivers food as a commodity in the market with its principles of calculability, predictability, efficiency (also described as a form of corporate bureaucracy), and control (Ritzer, 2011). Historically reliance on subsistence embedded foods in social relationships from production through consumption where mechanisms where food security mechanisms were in play throughout the system (Sahlins, 1972). With the transition to market-based production and exchange systems hunger in the presence of surplus production was rationalized via the market (Bohanan, 1957). In Alaska, Fazzino and Loring (2009) consider food security from the perspective of Alaska Native peoples, who have relocated from rural to urban centers of Alaska, utilize food service programs and have had to alter their lifestyle. Fazzino and Loring (2009) found that people preferred the food systems of rural Alaska as they allowed for a more holistic delivery of health in the sense that they offered higher levels of nutrition and maintain cultural continuity.

More broadly, change is occurring in the restructuring of kinship relationships, as aging policy is directly connected to economic, educational, and family policy (Kruse and Schmitt, 2012). The breakdown of extended families and multi-generational centered neighborhoods has reduced the capacity that families have to provide senior care. Taking care of seniors can be time consuming and economically costly, influencing the decision to exclude senior family members from the family residence (Spellerberg and Schelisch, 2015). Families may also become dependent on various social services so they shrink from this prior sense of responsibility and often now even lack the capacity to do so, thus creating a greater reliance and dependence on social services (Johnson, 1993). This creates a dilemma for seniors, particularly low-income seniors, in that they have often historically reduced family support, less prestige as respected elders in their families and in the community, pressure to be self-sufficient in ways that actually may not be to their health benefit and a dearth of limited or ineffective services provided by state agencies and non–profit organizations.

The aforementioned lack of senior care combined with larger neoliberal processes, which marginalize seniors, and commodify care including basic human necessities such as food and companionship, point to the need to provide safety nets for seniors who are increasingly finding themselves without a social support network. Thus, seniors rely more on social services including food provisioning services. Looking at these larger social trends helps inform service providers of why the recipients of their services are in need, what they are in need of, and the underlying social causes that create such a need.

Nutrition services including MOW, food banks, or soup kitchens, address, to varying degrees, the immediate food needs of those experiencing food insecurity. However, they seldom do anything about the structural issues that lead to food insecurity (Riches, 2002). Riches (2002) further argues that the way these services operate can allow governments to look away from food security issues. Tarasuk and Eakin (2003), who engaged in ethnographic research of a number of food banks in Ontario, Canada, argue that food banks provide a symbolic gesture, by providing insufficient food assistance to people, whilst allowing for the providers the psychic benefit of “doing good.” Tarasuk and Eakin (2003) found a division among those supplying the food (often corporations which would give their surplus foods to food banks), those distributing the food, and those receiving the food. Workers in food banks reported feeling unappreciated by recipients and powerless in decision-making regarding food and its delivery (Tarasuk and Eakin, 2003). Alarmingly, as the level of need in an area increased, the level of service provided decreased as they were not able to supply what was needed (Tarasuk and Eakin, 2003).

The Social Service Sociological Imagination is informative here in calling on those in Service organizations to consider their stated and potential roles in the lives of those that they serve in order to advocate for social change. Food banks are in a position to understand the needs of those that are food insecure as well as why they are food insecure. Such knowledge is necessary to tailor services to the needs of recipients and to develop social policy that reduces food insecurity and social alienation. The lack of a Social Service Sociological Imagination in these organizations results in services that are merely symbolic gestures (following Tarasuk and Eakin 2003) to assuage the need to respond, to do something, rather than addressing structural issues that maintain the need for services by refashioning citizens into consumers.

Although we are critical of the need for entities to go further, we realize that in the context of privatization and budget constraints, the perceptions of the possible may be limited by financial realities of Services delivery. The social needs of seniors are recognized outside of academic literature as there have been systematic attempts to address the needs of seniors, including MOW. MOW is just one of many senior service programs connected with the Older American Act (OAA) of 1965 and is often the first one that seniors seek out (Thomas and Mor, 2013). This is crucial as OAA programs lower the rates of relocation to nursing homes as they are designed to assist seniors to be as independent as possible (Thomas and Mor 2013). Thomas and Mor (2013) suggest that increased funding for such programs saves states more money in the long run by keeping older Americans in their own homes and out of nursing homes. In particular, they suggest that “investment in home-delivered meals may be one of the mechanisms that help to keep low-care individuals out of the NH (nursing homes).”(Thomas and Mor; 2013, 7).

Seniors’ overall quality of life includes not only food security, but mobility, health, and integration into society. These various factors also influence each other. In a study conducted by Wolfe et al (2003) seniors interviewed often pointed to financial difficulties and health issues as key concerns to remaining able to provide for one’s self (Wolfe et al 2003). Sanders et al (2005) assessed the daily experiences of homebound seniors in Ontario, finding that many seniors were limited in their daily activities by pain, mobility issues, hearing loss, decline of strength, and a fear of falling. These limitations were exacerbated by lack of access to affordable transportation leading many seniors to be relatively isolated and passing their time watching TV, or listing to books on tape or the radio.

Bullock and Osborne (1999) interviews and surveys of those involved in the Befrienders program (seniors, younger volunteers, and family caregivers) found that all involved looked forward to their interactions and learned much from each other. Family members of seniors involved with the program were relieved to have someone help out their elderly loved one (Bullock and Osborne 1999).

Bullock and Osborne (1999) initiated the first step to developing a Social Service Sociological Imagination by assessing how the Befrienders service fit into the lives of those involved. In doing so, they were able to identify how the service was working, how it could be improved and why it was important to seniors. This information is useful for advocating for social needs beyond what the service itself provides. It also supports a primary and foundational principle of applied social sciences, that change requires a system of cooperation with a particular focus of the client population itself and providing an accurate representation of the concerns of that population (Goodenough, 1963). This enables service organizations to see client needs as the clients consider them.

MOW attempts to alleviate some of the stress and challenges related to senior health. A cornerstone of health is access to healthy food. MOW is an important service providing food to seniors in most communities in the United States (Winterton et al, 2013). Social interaction is an important factor in health. Less social interaction for seniors means a greater risk for health issues (physical, mental, and emotional), require more support in attaining services, and have a less developed sense of community (Gitelson et al, 2008).

Studies have found that MOW improves the health of recipients (Sirey et al, 2008; Frongillo and Wolfe, 2010). For example, Frongillo and Wolfe’s (2010) study identifies the extent to which participation in MOW improves diet. Frongillo and Wolfe (2010) also found that that those living alone and in poverty experienced a greater level of health improvements by receiving MOW compared with those living with family and financially secure. However, this does not identify whether those living alone and in poverty (thus having the greatest need for the service) are taken to a point of “good” health and food security through their use of MOW. Sirey et al (2008) conducted a study to determine how receiving MOW reduces depression and suicidal tendencies among older adults. Together, these studies suggest that MOW improves both physical and mental health of homebound seniors.

Frongillo et al (2010) considered the diet and demographics of MOW clients in New York City as well as the social interactions between clients and meal deliverer. Frongillo et al (2010) found that: half of the clients chatted with the meal deliverer most of the time, 96% of clients were satisfied with the friendliness of the deliverer, and 77% of clients were satisfied with MOW (Frongillo et al, 2010). The current study builds of off Frongillo et al (2010) by using many of the same questions.

Lee et al (2008) highlight the importance of community involvement for MOW programs, both in terms of serving people and attaining volunteers. Lee et al (2008) assert that MOW is an important service, but they also suggest that many are unaware of it, or do not think about it much, and this can result in funding loss, which, in turn, reduces the ability for programs to serve the community. O’Dwyer and Timonen (2009) discovered that volunteers of MOW programs play a role in developing social relationships in the community. MOW can improve a sense of community not just for volunteers but also for staff and recipients of the meals because of the social interactions (O’Dwyer and Timonen 2009). The brief interaction between deliverer and receiver of the meal creates an avenue for social communication. The MOW service can further benefit meal recipients by acting as a “gateway” to other services (O’Dwyer and Timonen, 2009). In this way, MOW can, to an extent, counteract the trend of faceless delivery of food via the market in that it can provide a local response to local needs and encourage people to actually interact when providing services. The current study also attempts to examine the relationships that develop between volunteers and clients.

Overall, the literature suggests that the MOW improves the lives of those receiving the meals. Most studies have found that receiving home delivered meals improves seniors’ diets when compared to seniors not receiving MOW (Frongillo et al, 2010; Frongillo and Wolfe, 2010). In addition, studies suggest that the MOW service also improves mental health (Sirey et al, 2008), and provides social opportunities that would otherwise not be available (O’Dwyer and Timonen, 2009). MOW is a valuable service to seniors that are food insecure, which is likely to be more prevalent among seniors who are in poverty, live alone, and have less education. While this literature is helpful in determining the importance of the MOW service, it does not explicitly cover how MOW is situated vis-à-vis larger social trends. Nor does the literature cover how MOW fits into the lives of seniors receiving the service. This current study attempts to fill these gaps. We maintain that MOW programs stand in a position to demonstrate, provide, and advocate for better nutrition and food quality of seniors and could collaborate with other service providers.

4 Methods

ZH was involved in extensive participant observation while employed with the Juneau MOW program as the Coordinator for nearly two years. He was in charge of recruiting, training, and coordinating volunteers. He was also in charge of conducting intakes for potential recipients of the service, and organizing delivery routes. These tasks allowed an insider’s perspective on the program’s operation and actors. ZH served as the main point of contact for volunteers, clients, caregivers and family of clients, and professionals that make referrals to the program. In addition, ZH delivered the meals one or two times each month. The combination of various tasks and responsibilities allowed ZH to observe how the program operates and serves seniors of Juneau. ZH’s positon as the MOW Coordinator may also contribute to certain biases in the research, including desires for the program and for the needs of the clients, and this can effect perceptions. ZH also developed relationships with volunteers and clients and that can impact the responses received in the course of this study.

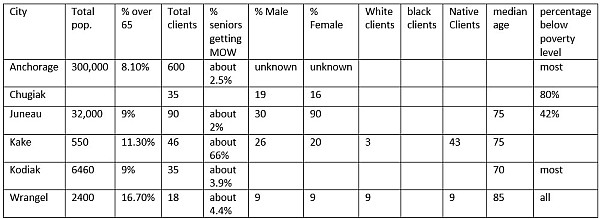

Basic data from other MOW programs in Alaska was obtained through email and phone communications with managers and coordinators of other MOW and senior centers in Alaska. To our knowledge, there had not been any previous communication among MOW programs in Alaska. Information was solicited from senior centers in: Wrangle, Anchorage, Kodiak, Chugiak/Eagle River, and Kake. Only Chugiak/Eagle River chose to participate. Questions were asked pertaining to the demographics of the people they serve, how long people tend to be enrolled in the program, why people discontinue the service, what meals are served, who prepares the meals, and if the meals are delivered by paid staff or volunteers (see appendix 1).

In stage one of the field research, ZH conducted semi-structured interviews, telephonic and face-to-face in fall 2013, gathering quantitative and qualitative data from meal recipients (N=9), some family members of MOW clients (N=2), and volunteers (N=12). This earlier work was supplemented by additional semi-structured interviews of clients. [2] The interviews were conducted in the homes of the clients and lasted anywhere from 15 minutes to an hour. The intent of the interviews was to get a more in-depth understanding of the daily lives of MOW recipients and what the service means to them (see appendix 2 for interview questions). Each interview began with a 24-hour recall exercise, where the client would describe the activities of the 24 hours before the interview began.

Seventeen clients were randomly selected (by assigning a number to each client and randomly selecting numbers through a computer generator) to be interviewed. Eight agreed to participate in interviews.

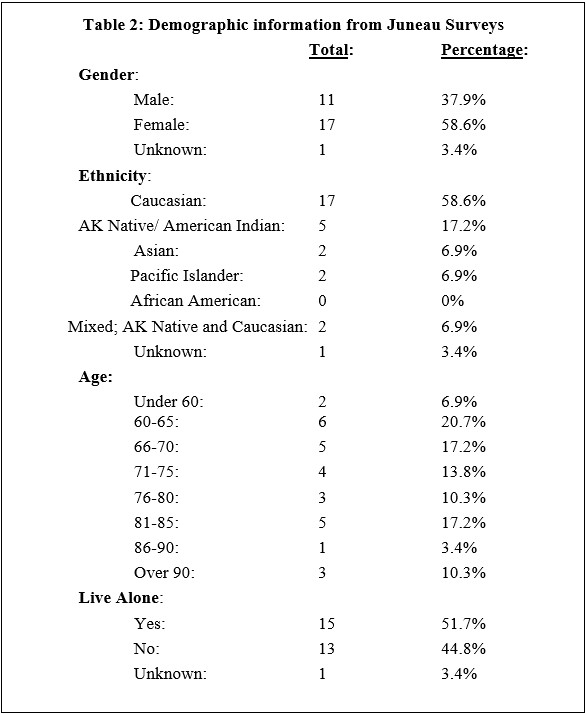

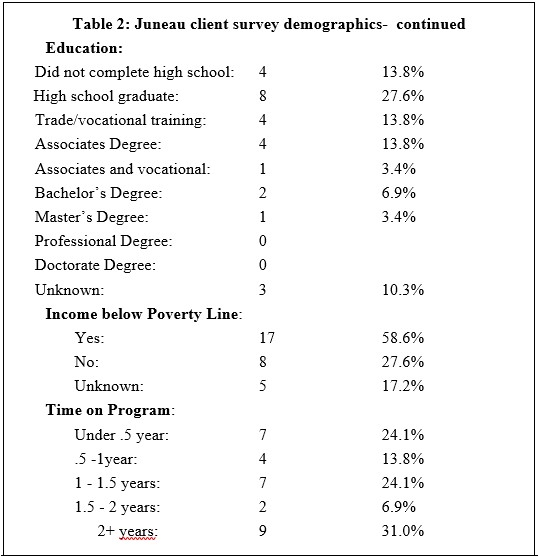

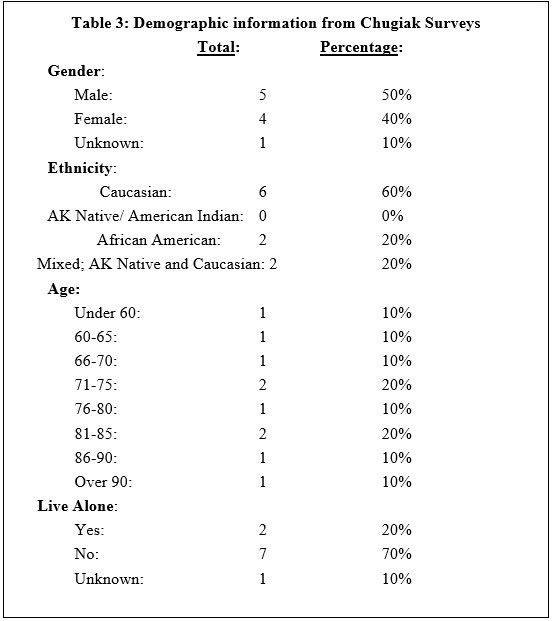

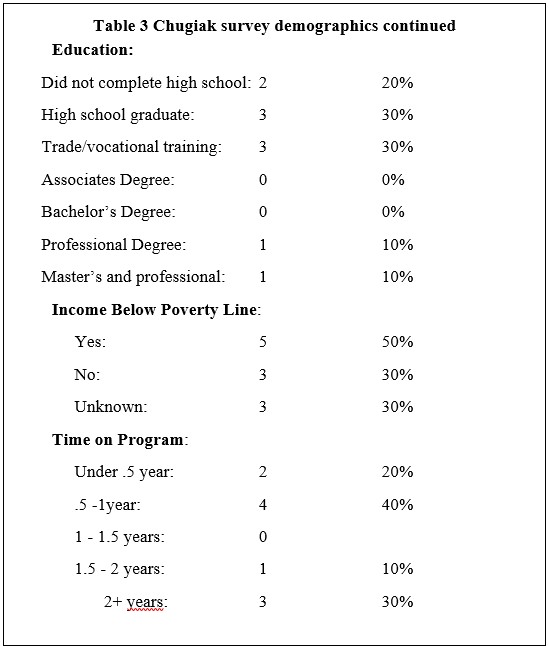

The interviews supplemented data that was collected through written surveys of clients in both Juneau and Chugiak (N= 125, with 90 from Juneau and 35 from Chugiak). The response rate for the client surveys in both Juneau and Chugiak/Eagle River was (N=39) 31.2% combined and (N=29) 32.2% and (N=10) 28.6% respectively (see table 2 and 3 for survey demographic data). The questions were designed to assess the lives of clients and how the MOW affects them (see appendix 2).

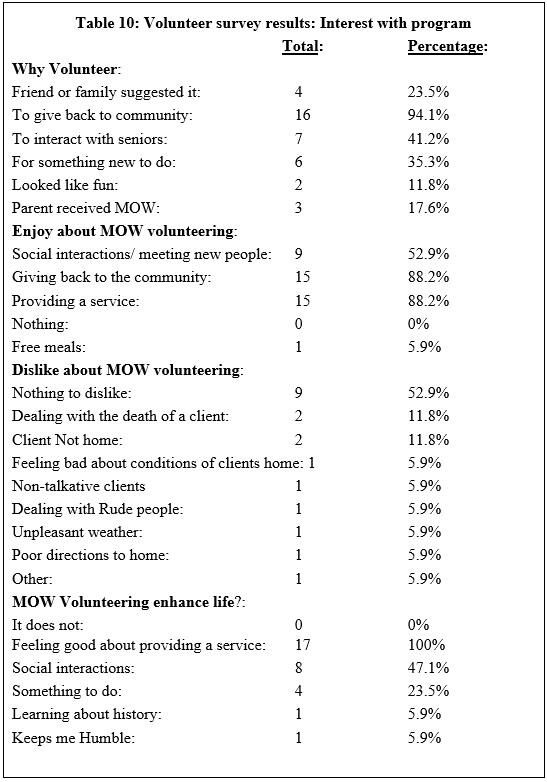

Volunteers in Juneau were also surveyed. Most volunteers that completed the survey did so through email (N=30). Ten volunteers responded to the survey on paper copies. The volunteer survey response was higher at about 45% (17/38 total responses). The volunteer survey collected data on who volunteers, why, and what their experiences with the program are (see appendix 3).

The original intent was to conduct a state-wide survey of MOW recipients, volunteers, staff, family caregivers, and health care professionals that make referrals to MOW. This, however, was infeasible as the needed communication channels and rapport were not in place, especially with family caregivers. There is little communication between MOW and family of the clients and the only contact information that MOW possesses is for the client and their one emergency contact. Thus, survey distribution was limited to Juneau’s MOW clients, Chugiak’s clients, and Juneau’s volunteers. From the surveys descriptive statistics were compiled and considered that provide potential insight into perceptions of clients and volunteers in MOW’s programs in Juneau and Chugiak.

5 Results

This study sought to understand clients in terms of: 1. how they perceived the service, including their overall satisfaction with MOW; 2. how they perceived the interactions with deliverers; 3. their food security; and 4. their daily lived experience. This study also sought to understand volunteers in terms of: 1. their general characteristics, 2. their level community involvement; 3.how they perceived the clients, their needs, and their interactions with them; 4. their interaction and consideration of clients beyond the meal delivery.

5.1 Demographics

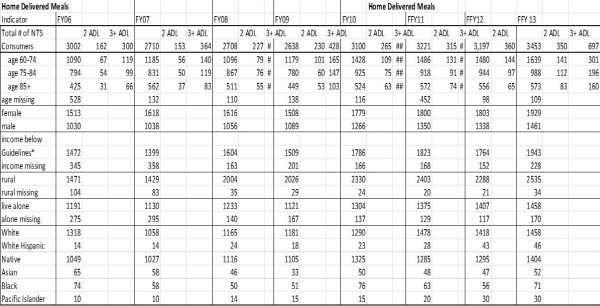

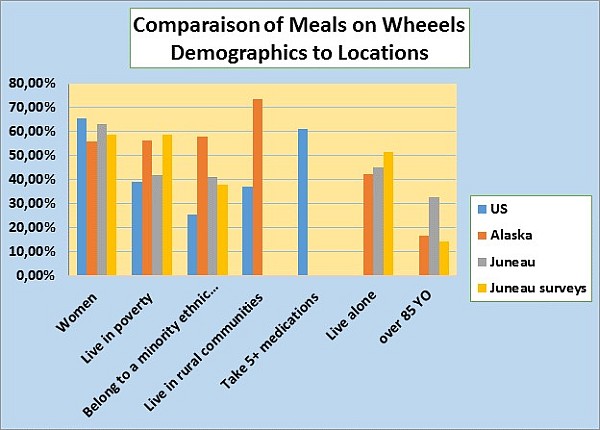

Figure 1 shows how the Juneau MOW demographic data compares with the overall MOW demographics of Alaska and also with the overall national MOW demographic data. The percentage of seniors receiving MOW in Juneau is around 3.7%, this is lower than the State average as a whole, which is 5.2% of seniors (United States Census Bureau, 2013). As a State, Alaska has more MOW clients that live in poverty, belong to an ethnic minority group, and live in rural communities than the rest of the country (see figure 1). The percentage of Juneau clients that are below the poverty line is far lower than that of Alaska as whole; however it is just slightly higher than that of the national average. At all three levels, city, state, and national, seniors living in poverty are overrepresented in MOW programs (Administration on Aging, 2013; Meals on Wheels America, 2013). Juneau MOW recipients are also more likely to be living alone and tend to be older than those in the rest of the state (see table 4 and table 5).

Figure 1:

US numbers from MOWAA (2011). Alaska numbers from ACoA

Table 4: Alaska MOW numbers by municipality

Table 5: Alaska statewide HDM client demographics.

When comparing the Juneau MOW clients to those in other municipalities of Alaska, (based on data provided over the phone by MOW and senior center managers), Juneau MOW clients are better off in terms of food security, financial stress, and isolation (see table 4 and 5). While the average age of MOW clients is about the same all around the state, seniors living below the poverty line are less frequent in the Juneau MOW program. In other parts of Alaska, well over 70% of MOW recipients are living alone and around the same percentage are living below the poverty line (see table 4 and 5) although state-wide 56% of MOW recipients are below the poverty line and 42% live alone (Administration on Aging, 2013). 41% live below the poverty line and 50% of the clients live alone in Juneau (see table 1). Alaska as a whole and Juneau specifically have a higher percentage of MOW recipients living in poverty (56.3% and 41.8% respectively) than the national MOW averages (39%)(see figure 1). Seniors that live with someone else most commonly, according to the surveys, live with a spouse. Some seniors live with their children. Seniors that live with their children tend to be better off financially. Six clients reported living with their children and of those only one is clearly living in a low income household.

This demographic information about who is receiving MOW helps to situate MOW in relation to the overall societal care of elders. The seniors that rely the most on MOW are those that live alone and have a lower socioeconomic status.

5.2 Food Security of MOW Clients:

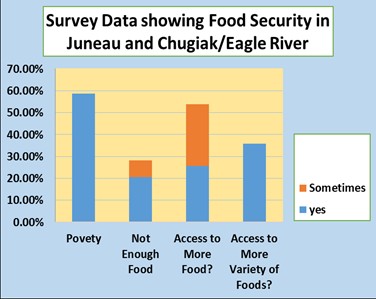

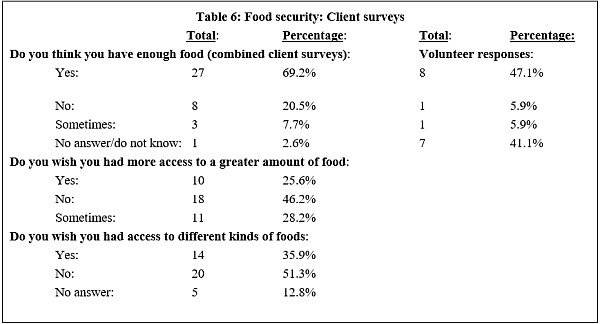

Overall, the data suggests that most MOW clients are comfortable with the food they have (see table 6); 69.2% said they had enough food (see figure 2 for survey responses indicating food insecurity). When asked if they wanted different kinds of foods 35.9% of respondents said yes, and just under 50% of those that said yes indicated that fresh produce was what they wanted. It is important to note that fresh produce is difficult to acquire in Southeast Alaska.

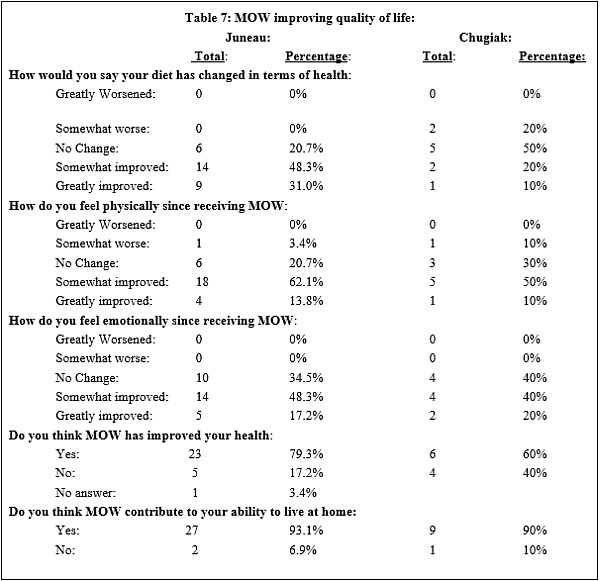

Figure 2. Food security

MOW fulfills its mission by contributing to the food security of recipients, with many reporting that the service “makes life easier.” This clearly came through in ZH’s daily work at MOW, as well as the surveys and interviews. Indeed, one survey respondent indicated numerous times, by adding notes in the margins, that MOW helps him to maintain a healthy diet. Another stated that the only fruits and vegetables she consumes are from MOW. Almost universal in both formal data collection and informal conversations with recipients is the idea of how much more difficult life would be if it were not for MOW. 93.1% of Juneau respondents and 90% of Chugiak respondents indicated that MOW allows them to remain at home (see table 7). Thus, MOW is improving food security and diet and makes living at home possible.

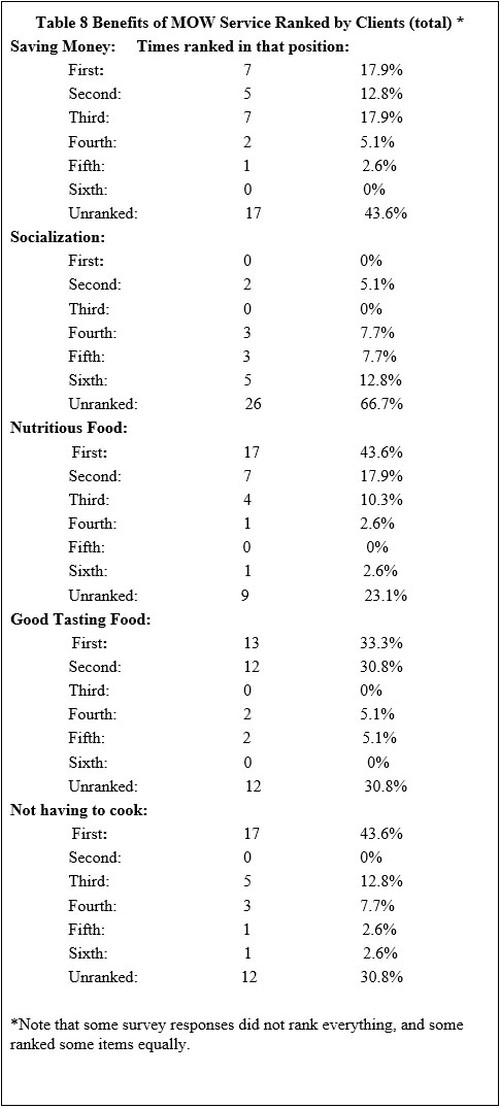

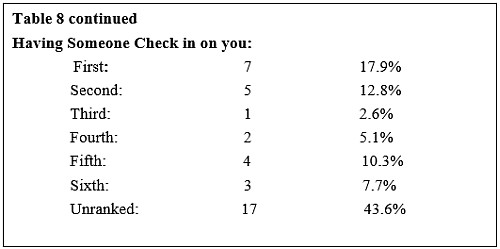

For seniors, food security is generally threatened by a variety of factors including: finances the ability to cook, and access to transportation. Preparation of the food and the quality of the food that was generally most appreciated. When asked to rank benefits of the service nutritional value, good tasting food, and not having to cook were highly ranked (see table 8).

MOW recipients living with family that have financial means, are the most comfortable in terms of food security, nevertheless the meals were appreciated. One man, John[3], for example, who is financially secure, greatly benefits from the meals. They have become the centerpiece of his diet even though he lives with his son’s family (wife and daughter), the family is not struggling financially, and they have plenty of food in the house. In addition, John has professional caregivers assisting him during the weekdays, including cooking for him. In John’s case, MOW is most helpful for his caregivers because it reduces their workload. For many others too, MOW is a helpful service for the client’s social-support network. The service provides relief to caregivers in terms of physical, emotional, and economic support.

Not surprisingly, the MOW service is of greatest importance for those that are food insecure. However, MOW only provides one meal five days a week. For some, like the John living with his family, the MOW service is enough. There are some recipients of the service that require more, and they are often the ones in a lower socioeconomic status. During the interviews even those that needed more nutritional services and were not receiving additional support, expressed gratitude and appreciation of MOW service. Many indicated that it was the highlight of their day. Such appreciation also came across in the survey data as well: with clients stating that MOW helped them maintain their health (see table 9).

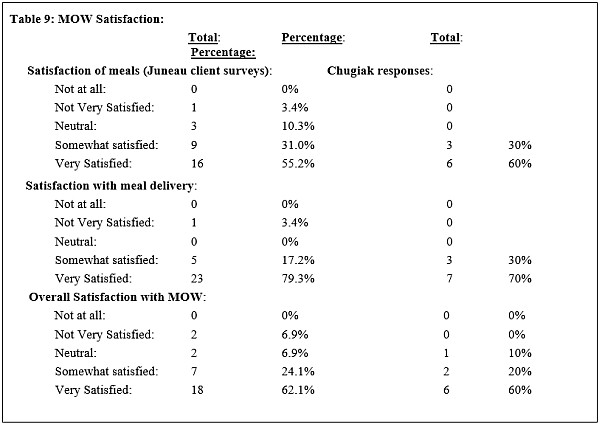

5.3 Satisfaction with Meals on Wheels

Most people involved in the MOW program, whether clients or volunteers, expressed satisfaction with how the program is running (see table 9 and table 10). It is important to note that given the fact that the research was conducted through MOW, research participants may have felt pressured to respond a certain way based on their receiving a service from MOW.

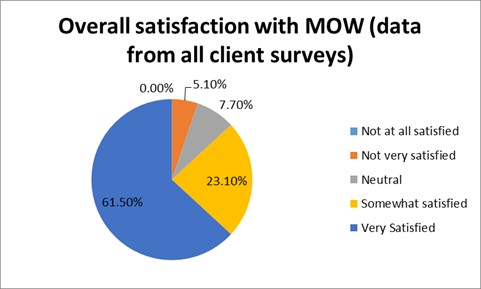

When asked, both MOW clients and volunteers express satisfaction with the program. Just over 50% of volunteers surveyed said there was “nothing to dislike” about the MOW program. Table 9 shows the satisfaction of MOW clients in both Juneau and Chugiak with the meals, the delivery service and the program overall (figure 3 presents overall satisfaction of clients with MOW).

Figure 3.

While overall clients expressed satisfaction with the service, those that interacted with the volunteers more indicated higher levels of satisfaction. The client survey results revealed a positive correlation between the amounts of time spent talking with the volunteers, as well as the frequency of the interactions, and satisfaction levels. In fact, there were only two variables that were found to correlate with satisfaction of MOW: the amount of time spent talking with the meal deliverers, and the degree to which MOW is perceived to contribute to improvements in nutrition intake.

Data collected from interview also indicated that increased socialization with MOW volunteers was also accompanied by an increase in appreciation for the service. While all the MOW recipients interviewed stated, to some degree, during the interview how much they appreciate the meal service, the level of importance and impact on their life varied. Some interviewees discussed MOW extensively during the 24-hour recall, and others did not. In fact, Dianne did not even mention MOW at all in her 24-hour recall. The more involved (in terms of how long the interaction was, and how involved each participant was in the interaction) the interaction with the meal deliverer, the more frequently MOW was mentioned in the 24-hour recall. Those that indicated more interactions with the delivers tended to talk more about MOW and how much their day was influenced by MOW.

Data also revealed that this relationship between socialization and satisfaction with the service was unconscious for most meal recipients. When clients were asked in the survey to rank which MOW benefits were of greatest importance to them, socialization was never ranked first and went unranked more than any other option (66.7% did not rank it at all. See table 8).

If clients are dissatisfied with the service, they rarely expressed it. Since 2012, 7% of clients that have discontinued the service reported being dissatisfied with MOW. Most recipients probably do not have the luxury of discontinuing a service just because they do not like it. On the other hand, there is nothing in the data collected which would allow for a presumption of client dissatisfaction. Over the years ZH has heard few complaints about MOW, and most are from volunteers and not clients. Every once in a while a volunteer would make a negative comment regarding the appearance of the food. Volunteers also rarely praised the food, and even though they are offered a free meal when they deliver, only six volunteers (16%) took up that offer on a regular basis. Nevertheless, most of the clients reported that they are satisfied and appreciative of the meal service, and most volunteers are glad to provide a service (see table 9 and 10).

5.4 Recipient and Deliverer Interactions

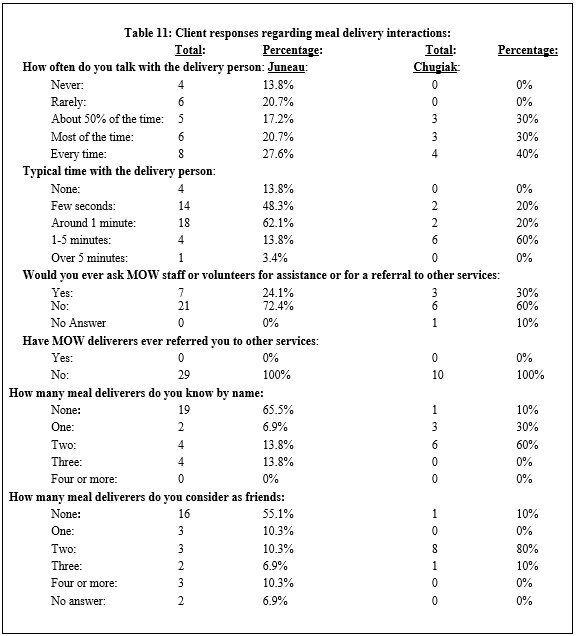

The majority of interactions between the clients and volunteers are rather superficial or even non-existent. Thirteen percent of the Juneau respondents reported that they never interacted with the meal deliverer (See Table 11). In some of these instances an intermediary, such as a caregiver, may take the meal on behalf of the recipient. Contact between client and deliverer is often brief with only 17% Juneau respondents indicating that their interactions are typically over one minute (Tables 10 and 11). Chugiak clients report spending more time talking with the meal deliverer, 60% said one to five minutes is the average amount of communication time.

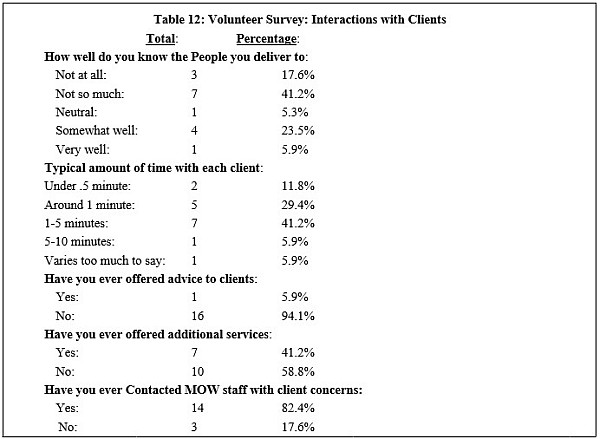

In addition, in most cases there does not appear to be a significantly meaningful relationship between MOW volunteers and clients. The most common discussion topics, according to the volunteer surveys, are: the weather (88.2%.), the meal (76.5%), pets (70.1%), health (41.2%), and family (29.4%). We hypothesize that as relationships develop between MOW clients and volunteers, discussions will increasingly reach topics that are more personal, such as health and family. Future research could examine how these relationships develop over time.

A few times ZH has accompanied volunteers as they delivered meals. ZH noticed that most often the volunteer knocks on the door and hands over the food while smiling. Some MOW recipients just take the food, say “thank you” and close the door. Most times the volunteer will also ask how the person is doing. Usually the response of the client is positive and brief.

Survey results corroborated the fact that most interactions are brief and superficial. When asked how well they know MOW clients they deliver to, 41% of volunteers said “not so much” and 17% said “not at all” (see table 9). When asked if they thought MOW clients have enough food, around 40% said they did not know (see table 6).

The lack of communication contributes to a lack of understanding between MOW clients and volunteers. For example, survey results indicated that 20% of clients did not have enough food (see table 6). Yet, when asked, only one volunteer said that MOW clients do not have enough food. MOW recipients also indicated that they do not know the meal deliverers very well, and do not seem interested in asking them for anything (see table 12)[4]. Over 60% of MOW recipients do not know any of the volunteers by name. Despite this, those receiving meals still consider deliverers as a “friend.” 69% of client survey respondents also said they would not ask volunteers or staff for anything else. Most MOW recipients were not interested in asking for anything or sharing concerns they have with MOW staff or volunteers. For some clients this does not matter much as they have people already providing care for them, but there are some clients that do not receive other services, and do not have anyone to talk to about various issues and needs they have.

One time ZH delivered a meal to Simon, a MOW recipient and family friend for many years, Simon mentioned that he is always in pain, but he never tells the volunteers when they ask because he “does not want to bother them with his troubles.” When ZH delivered meals he always asked the clients how they were feeling and asked something pertaining to their satisfaction with the service. Despite ZH’s attempts to communicate further, the interactions were often brief with very little information being exchanged.

Some volunteers and clients have developed a more substantial relationship with each other, such that volunteers will schedule their delivery route so that they have more time to visit with particular clients.[5] While some of these relationships existed prior to MOW, most are developed through the MOW deliveries. These more intimate relationships appear to be the exception rather than the rule, as deliverers reported knowing the people they deliver meals to” “not so much” (41%) or “not at all” (17%) (See Table 12).

As MOW does not currently emphasize social interactions, the lack of substantial social interactions is not necessarily a concern in program delivery. And, overall, most people involved in the program, including volunteers, clients, and MOW staff, express satisfaction with the level of social interaction. MOW clients are appreciative of the interaction and look forward to a friendly person coming to their home to bring them food. The client interviewees highlighted their perceptions of the (un)friendliness of the meal deliverer as important. Despite reports that minimal interactions were the norm, a minimum amount of interaction was expected. All of the interviewees expressed frustration with unfriendly delivers that seemed disinterested in them and left without saying anything.

While MOW certainly does not need to emphasize the socialization aspect of the service in order to support “independant” living, doing so could improve the overall quality of care provided. For example, part of the value of the service is having someone check-up on homebound seniors. Volunteers are encouraged to contact the MOW coordinator if they have concerns regarding a client. Most volunteers (80% of survey respondents) have contacted the MOW Coordinator with client concerns (see table 12). Concerns ranged from a client not being at home, to the volunteer’s perception that client’s health is deteriorating. ZH received one phone call per week, on average, from volunteers expressing concern about MOW recipients they deliver to. In many cases, the concern was simply that the client was not home. Calls from volunteers about a specific issue with a clients were less common, but did occur a few times per month. If there was better communication between the volunteers and clients, as well as between volunteers and MOW staff, concerned phone calls may have been more frequent. This could have allowed MOW to act as a bridge connecting MOW clients to other services.

There is interest among both volunteers and clients for further developing social interaction. Susan, a MOW recipient, mentioned in the interview that she would like to talk with the volunteers more, but she does not know what to say. Susan shared that volunteers did not “seem to have much to say.” ZH has heard this sentiment from other MOW recipients over the years as well. Both volunteers and clients say that how talkative they are is based on their assessment of how much the other person wants to talk. In doing so conversations tend to be shorter rather than longer. Thus, the MOW program has the potential to further develop the social component.[6] Such development would allow for the development of a Social Service Sociological Imagination in that as communication channels are enhanced, the organizational understanding of client perceptions, realities and needs grows.

5.5 Lives and Needs of MOW Client:

All interviews began by doing a 24-hour recall, so as to get an idea of what a typical day is like for MOW recipients. All of the interviewees had a difficult time discussing the events of just one 24 hour period. This was largely due to poor memory, but also because of how “the days blended together.”[7] The typical 24-hour recall would begin with something along the lines of “well, I woke up around 7:30AM, like I usually do” and from there they would go on discussing what they “usually” do, as opposed to the specific events of the past 24-hours. Efforts were made in the interview to keep the focus just on the previous 24 hours but many interviewees had a hard time remembering details of the day prior.

Homebound seniors experience little variation in their day-to-day lives. For some seniors, reliance on caregivers structures when daily activities are even possible. For example, John, who has MS, has fulltime caregivers and is largely dependent on them. Thus, what he does and when he does things is largely dependent on when his caregivers are available. Ann and Larry provide another example. Ann is the primary care provider for her husband Larry. Larry is bedridden, and dependent on his wife for just about everything from food to hygiene. His day consists primarily of sleeping, eating a meal or two, and watching TV in his bedroom. These events are all based around Ann’s schedule. Ann spends her days taking care of the house, watching TV, and catering to her husband’s needs. While Ann and Larry had each other for company, Larry’s health issues and sleep schedule limited their interactions.

MOW clients tend to spend a large portion of their time alone. Many clients reported spending a lot of time with electric entertainment, with many reporting three or more hours of television per day. Reading is also a popular pastime, however, trouble with eyes limited this for some. Jackie, also mentioned that she listens to the radio most of the day, and that is where she gets her news and entertainment. Through these media sources, seniors maintain some sense of connection to society. They learn about current events from the news, either in the newspaper, online (although, most reported being computer illiterate), from the radio, or most commonly the television. Mostly, though these media sources were relied on for entertainment more than for the news. For many, these media sources were their primary source of information as well as hearing another person’s voice.

Opportunities for social interaction for MOW recipients tend to be limited by financial strain, mobility issues, and health constraints. There were three clients that discussed feeling “isolated” before being prompted to discuss social interactions. Rachel even went to so far as to say she “feels like no one cares”. Lack of available and easy to use transportation was often cited as a reason for such isolation. All three interviewees that mentioned feeling isolated are financially struggling and two of them live in low-income housing. It is the combination of financial strain and a lack of social support that contributes to senior isolation. There are some MOW clients that live in poverty, but have social support and that enables mobility.

Many MOW seniors are isolated because they do not have friends or family that visit and interact with them regularly. About 48% of clients who reported living alone, also indicated that they do not have any family living in the same municipality as them. Even MOW recipients that have friends and family living near them still expressed feeling isolated. In large part this is due to the breakdown of extended families and also the lack of a social space for seniors. Seniors are not woven into the day-to-day lives of most non-seniors unless it is part of their job.

Childcare is one way in which seniors can have a prominent role in the family and society. For example, George and Linda, a married couple both receiving MOW, have a four year old granddaughter that they watch for a few hours per day. Both Linda and George, reflecting on the care they provide to their granddaughter, expressed happiness and feelings of being useful. However, George and Linda’s situation is rare. Most, MOW recipients are not capable of taking care of children due to their health issues. So while the social space for seniors is limited, there are even fewer opportunities for social connection for homebound seniors.

6 Discussion and Conclusion

MOW is just one service that is available to seniors. The task of this study was two-fold. First, to assess the role of MOW for its clients and second, to situate MOW within the larger social context. Both of these objectives serve the function of developing a Social Service Sociological Imagination. When social services possess a Sociological Imagination they can do more than merely provide a stagnant service, but can help shape society for the betterment of those in need. This current study begins to develop such a Social Service Sociological Imagination for MOW, but the same theoretical framework can easily be applied to other social services.

The service that MOW provides has become increasingly important with various societal changes. The growing need for senior services is apparent in trends such as: the loss of geographically localized communities, a breakdown of extended families (Kruse and Schmitt, 2012; Spellerberg and Schelisch, 2015), and industrialized market-based food systems (Bohannon,1957; Fazzino and Loring, 2009; Ritzer, 2011; Sahlins, 1972) . Taken together, communities and families are less able and willing to provide support for seniors, making senior services important for older people.

Overall, our results indicate that MOW clearly achieves its stated goal of providing a supplementary meal source for homebound seniors. MOW assists clients and their care providers by offering a nutritious ready-to-eat meal. In addition, following (Frongillo et al, 2010) we found that MOW also creates social channels. MOW connects people who otherwise might not be connected. As such, MOW contributes to a reshaping of the community and expanding social networks.

MOW provides a great opportunity to develop the community, and learn about the needs of seniors. This is an opportunity that is often missed. As the data shows, most of the volunteers do not feel knowledgeable about the seniors they serve and interactions are often brief (see table 12). It is important to note that, for the most part, those involved with MOW— staff, volunteers and clients—were content with the level of interaction. At the same time, both volunteers and clients indicated an interest in socializing more, but were unsure of how to do that. The desire to interact shows that interaction—even when superficial—is socially meaningful for seniors, in part because it conveys caring. MOW staff should take this as an opportunity to facilitate more meaningful interaction between clients and volunteers.

Adapting the service to provide a more reflexive and holistic service that encourages the development of social relationships would not be complicated. As this research points out, there is an interest and an opportunity. It just needs to be tapped into. Doing so begins with how volunteers are trained and the way their role is explained to them. Volunteers should be trained on how to communicate and converse with homebound seniors. In addition to training, opportunities for social interaction should be increased. For example, volunteers could take meal suggestions from clients. This would give clients a voice in the operation of the service and it could build a bond with volunteers. Another method could be for volunteers to occasionally share a meal with clients or to work with the client to set up the eating space. These ideas encourage the clients and volunteers to bond over the meal. Doing so could improve the value of the service. It could also enhance the organization’s understanding of its clients and their needs.

While the MOW program claims to be a “gateway” service, and in some cases it is, it is troubling that many clients do not feel it appropriate to discuss issues they are having or ask for anything from MOW volunteers or even staff. It is doubly problematic, in that, for some clients, the MOW deliverer is the only person they interact with each day. If clients do not approach the deliverer for assistance, then who? This is just one reason why the MOW program should focus more on the social components of the service so that it can properly fulfil its role as a “gateway” service. As Lamb (2014) notes, this lack of communication is likely viewed as culturally appropriate given seniors’ attempts to remain independent. This is important because seniors are, overall, unlikely to change, thus MOW must adapt to them.

The attitude that the social component of the service is important is not shared by all within the organization. In fact, one of the senior service managers at the organization expressed “that ZH was too focused on the social aspect of the service.”[8] The attitude that this manager was taking reflected her rigid belief that MOW was supposed to be a top-down delivery system.

Yet, there is an interest at the institutional level in what MOW provides beyond the food. The presentation given by ZH on January 30, 2014, to the Alaska Mental Health Trust was all about how the service provides more than food. The AMHT had an interest in taking a holistic view of senior services. In addition the data from this study and the literature review both show that increased social capital for seniors improves perceived quality of life, enhances the quality of services, and has positive effects on health. If MOW can better develop relationships and networks of information exchange, it may enhance the quality of the service. It may also increase volunteerism and attain additional funding, which as Lee et al (2008) pointed out are common challenges for MOW programs. Perhaps most importantly the opening up of such social networks could work to bring the community together. It could further develop intergenerational communication and collaboration.

MOW clients generally have needs that extend beyond receiving a meal five days per week. Sometimes, their other needs are met but sometimes they are not. For some clients, the MOW volunteer is the only person they interact with and the only person who could help them reach out to other service providers. Simon mentioned that he did not want to burden MOW volunteers with his troubles. Luckily for Simon he has a strong support system in the community and his needs are met. But what happens to those whose needs are not being met? Without the proper communication channels, such communication of needs does not occur and needs go unmet. Again, the MOW service presents an opportunity to provide holistic services to MOW recipients that can extend beyond just a nutritional service.

Studies like this provide insight into the role and value of service organizations. This study was able to show the ways that MOW is succeeding and where more can be done. The data from this study can then be used to improve the quality of the service and to tailor it to the specific needs of clients. This study can also be used to develop a Social Service Sociological Imagination. By understanding the role of the service, MOW can adjust the interactions to best suit the needs of clients.

The results of this study can be used to improve, and possibly broaden, the MOW service by providing key information about MOW’s significance (see Lee et al., 2008). These findings can also be used to improve to senior services more generally. The results shed light onto the interactions and significance that the MOW service provides for homebound seniors. Knowing how MOW clients rely on the service and perceive the service can be useful in considering changes to service to better serve the needs of clients. In addition, such knowledge can be used to improve senior services more generally. MOW provides a unique opportunity to get a glimpse into the life of homebound seniors. This information can be shared with other service providers. In addition, this information can be shared with policy makers to develop senior and family policies and laws that alleviate some of the challenges that seniors and their families face.

While the results of this study are valuable in understanding the role MOW plays in the lives of homebound seniors, the daily MOW interactions are even more illuminating. Much more information can be gathered during daily interactions than with periodical studies. As MOW develops a Social Service Sociological Imagination, the manner in which services are provided can be adjusted to: 1) gain a better understanding of the needs of clients and 2) utilize the frequent client contact and interaction to empower clients by giving them a connection to active members of society.

Internally and programmatically MOW could act to emphasize social interactions. The training of volunteers could be more focused on interacting with the clients and picking up on their needs. Particularly, this training would: 1)Develop the deliverer’s “gateway” role to providing other services that seniors may be need of, and 2)develop the deliverer’s ability to craft meaningful dialogue and social interactions with seniors. Additionally, efforts could be made to make the clients more comfortable interacting with the volunteers and MOW. These efforts would enable the program to develop a Social Service Sociological Imagination. Which, in turn, would greatly enhance the service provided, the ability to partner with other organizations, and in advocacy efforts. In addition, the increased attention on the social aspects of the service helps connect homebound seniors to the community.

The application of a Social Service Sociological Imagination allows an organization to situate itself in the lives of its clients in a way that all the needs of their clients are met. An organization in possession of a Social Service Sociological Imagination can collaborate with other service providers to ensure that clients’ many needs are met. The organization can also empower clients by giving them a voice in society. Additionally, the organization can give clients a voice in how services are provided. An organization in possession of a Social Service Sociological Imagination is able to adapt to client needs.

To develop a Social Service Sociological Imagination, organizations need to encourage a deep interest and care for clients and promote creativity and active engagement with clients. Organizations should empower employees and volunteers to think creatively and try to provide as much service as they can. Those working directly with clients should empower clients to advocate for their needs. In creating and maintaining these collaborations everyone, from clients to the top decision makers, can work together to have the service address the needs of clients.

Certainly there are opportunities for MOW’s expansion. These opportunities, however, are limited by a series of interrelated factors, including, but not limited to, increased privatization of services, the decreased state spending for services, and increased competition among service organizations. These factors have all changed the way social service organizations operate. MOW, and many other social services, are not capable of addressing social structural issues, but, by their nature, can work to foster a greater awareness of the social realities faced by marginalized segments of society. Overcoming institutional momentum, fear of mission creep, and the neoliberal logic of aid are all obstacles which are ever-present in the contemporary landscape of services delivery. They are challenges that imagination (Mills 1959) and persistence may overcome. A reflexive and iterative approach where those receiving services are actively engaged in shaping the services they receive is imperative in improving relations within and between service organizations. This research provides a way to come to know seniors’ needs and desires better and understand the current gaps in services delivery.

Taken together, this research suggests avenues for further in-depth ethnographic examination of MOW. While this study assessed the lives of MOW clients, future research could assess the lives and needs of Juneau’s senior population as a whole. Is the MOW program properly serving the City and Borough of Juneau? In addition, it would be useful to measure the how MOW contributes to the health of clients and see if expansion of meal delivery is needed. Along the same lines, a longitudinal study examining changes in quality of life of seniors receiving MOW would also be useful in further understanding the role MOW has. The questions used in the current study can provide a baseline for a longitudinal study.

Research is time consuming and an investment, but is feasible in the context of service delivery. This research was conducted over the course of ten months with an estimated two hours per week, on average, spent all while ZH was working at MOW. This is research that can be done in the context of current constraints, if the desire is there. The instruments are intended to be used as a starting point for organizations that seek a greater integration of their programming to match the needs of clients. Developing a Social Service Sociological Imagination is possible, and needed.

References

Alaska Commission on Aging (N.D.) Meals on Wheels Demographic Information

Administration On Aging, www.aoa.gov, 2013. (accessed 4/2014).

Bohannon, P. (1957). Some Principles of Economic Exchange and Investment among the Tiv. American Anthropologist. 57(1): 60-70.

Bullock, J- R. & Osborne S. S. (1999). Seniors, Volunteers, and Families Perspectives of an Intergenerational Program in a Rural Community. Educational Gerontology. 25 (3): 237-251.

Corner, L., Brittain, K. & Bond, J. (2006). Social Aspects of Aging. Women’s Health Medicine 3 (2): 78-80.

Farquhar, C., Lowe, J. & Campbell, J. (2007). Trends in Aging Funding and Current Areas of Foundation Interest. Generations. 31 (2): 50-53.

Fazzino, D. & Loring, P. (2009). From Crisis to Cumulative Effects: Food Security Challenges in Alaska. Napa Bulletin. 32: 152-177.

Frongillo, E., Isaacman, T., Horan, C., Wethington, E. & Pillemer, Karl. (2010). Adequacy of and Satisfaction with Delivery and Use of Home-Delivered Meals. Journal of Nutrition for the Elderly. 29: 211-226.

Frongillo, E. & Wolfe, W. (2010. Impact of Participation in Home-Delivered Meals on Nutrient Intake, Dietary Patterns, and Food Insecurity of Older Persons in New York State. Journal of Nutrition for the Elderly. 29: 293-310.

Gitelson, R., Ho, C., Fitzpatrick, T., Case, A. & McCabe, J. (2008). 26 (3): 136-151

Goodenough, W. (1963). Cooperation in Change: an Anthropological Approach to Community Development. California: Russell Sage Foundation.

Hasenfeld, Y. & Garrow, E. (2012). Nonprofit Human-Service Organizations, Social Rights, and Advocacy in a Neoliberal Welfare State. Social Service Review. 86( 2): 295-322.

Hay, M. C. (2010). Suffering in a Productive World: Chronic Illness, Visibility, and the Space Beyond Agency. American Ethnologist 37(2): 259-274.

Katz, I. & Key, K. H. (2014). Reframing Human Services: Why and How. Policy & Practice. 72(1): 9-35.

Kruse, A. & Schmitt, E. (2012). Generativity as a Route to Active Ageing. Current Gerontology and Geriatrics Research. 2012: 1-9.

Johnson, C. (1993). The Prolongation of Life and the Extension of Family Relationships: the Families of the Oldest Old. In Family, Self, and Society: Toward a New Agenda for Family Research. Phillip Cowan et al, eds. 317-331. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, inc.

Lamb, Sarah. (2014). Permanent Personhood or Meaningful Decline? Toward a Critical Anthropology of Successful Aging. Journal of Aging Studies. 29: 41-52.

Lee, J. S., Frongillo, E., Keating, M., Deutsch, L., Daitchman, J. & Frongillo, D. (2008). Targeting of Home-Delivered Meals Programs to Older Adults in the United States. Journal of Nutrition for the Elderly. 27(3/4): 405-415.

Liang, J. & Luo, B. (2012). Toward a discourse shift in social gerontology: From successful aging to harmonious aging. Journal of Aging Studies. 26(3): 327-334.

Millen, B. E., Ohls, J.C., Ponza, M. & McCool, A.C. (2002). The elderly nutrition program: an effective national framework for preventive nutrition interventions. Journal of the American Dietetic Association 102 (2): 234-240.

Meals on Wheels America, www.mowaa.org (2013) Accessed 4/21/2014.

Mills, W. C. (1959). The Sociological Imagination. New York: Oxford University Press.

O’Dwyer, C. & Timonen, V. (2009). Doomed to Extinction? The Nature and future of Volunteering for Meals-on- Wheels services. Voluntas. 20: 35-49.

Riches, G. (2002). Food Banks and Food Security: Welfare Reform, Human Rights and Social Policy. Lessons from Canada? Social Policy and Administration. 36 (6): 648-663.

Sahlins, M. (1972). Stone Age Economics. New York: Aldine de Gruyter

Sanders, S., Polgar, J., Kloseck, M., & Crilly, R. (2005). Homebound Older Individuals Living in the Community: A Pilot Study. Physical & Occupational Therapy In Geriatrics, 23(2/3): 145-160.

Sirey, J. A., Bruce, M., Carpenter, M., Booker, D., Reid, M., Newell, K. & Alexopoulos, G. (2008). Depressive Symptoms and Suicidal Ideation Among Older Adults Receiving Home Delivered Meals. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 23: 1306-1311.

Spellerberg, A. & Schelisch, L. (2015). Emerging Trends: Shaping Age by Technology and Social Bonds. Emerging Trends in the Social and Behavioral Sciences: An Interdisciplinary, Searchable, and Linkable Resource. 1–14.

Tarasuk, V. & Eakin, J. (2003). Charitable food assistance as symbolic gesture: an ethnographic study of food banks in Ontario. Social Science and Medicine. 56: 1505-1515.

Thomas, K. & Mor, V. (2013). The Relationship between Older Americans Act Title III State Expenditures and Prevalence of Low-Care Nursing Home Residents. Health Services Research. 48 (3): 1215-1226.

Tomaka, J., Thompson, S. & Palacios, R. (2006). The Relation of Social Isolation, Loneliness, and Social Support to Disease Outcomes Among the Elderly. Journal of Aging and Health. 18(3): 359-384.

United States Census Bureau. (2013). QuickFacts. www.quickfacts.census.gov ( accessed 2/2014)

Winterton, R., Warburton, J. & Oppenheimer, M. (2013). The future for Meals on Wheels? Reviewing innovative approaches to meal provision for ageing populations. International Journal of Social Welfare. 22: 141-151

Wolfe, W., Frongillo, E. & Valois, P. (2003). Understanding the Experience of Food Insecurity by Elders Suggests Ways to Improve Its Measurement. Journal of Nutrition. 113 (9): 2762-2769.

Woolford, A. & Curran, A. (2013). Community Positions, Neoliberal Dispositions: Managing Nonprofit Social Services Within the Bureaucratic Field. Critical Sociology. 39 (1): 45-63.

Zachary Hozid

Vermont Law School

164 Chelsea St, South Royalton, VT, USA 05068

zachhozid@gmail.com

David Fazzino

Bloomsburg

University of Pennsylvania

400 East 2nd

Street, Bloomsburg, PA, USA 17815

dfazzino@bloomu.edu

Appendix 1: Client Survey Questions:

Why did you initially sign up for Meals on Wheels?

Medical referral

Recovering from surgery

Recovering from illness

Spouse was receiving meals

Changes in health limited what you could do on your own

Other:_________________________

Who initially signed you up for Meals on Wheels?

Self

Referred by health care professional

Family

Other: _______________________

How long have you been receiving Meals on Wheels?

Under 6 months

6months- 1 year

1 year- 1.5 years

1.5-2 years

Over 2 years

In the past Year how often have you been hospitalized?

0

1

2

3

4 or more times

How many meals do you eat per day?

0

1

2

3

More than 3

How many of the meals you eat each day come from Meals on Wheels?

Less than one full meal

1

1.5

2

Over two meals are from Meals on Wheels food

Where do you get the rest of your food? Check all that apply

Wal-Mart

Costco

Fred Meyers

Local grocery stores

Local Gardens/Farms

Subsistence

Other:_____________________

Who gets your groceries for you?

Myself

Friends

Family

Neighbors

Professional care providers

Other:___________________

Who pays for your groceries?

Myself

Friends

Family

Neighbors

Other:___________________

Do you think you have enough food?

Yes

No

sometimes

Do you wish you had access to a greater amount of food?

Yes

No

Sometimes

Do you wish you had access to different kinds of foods?

Yes

If yes, what kinds of foods?

No

Please rank the following potential benefits of Meals on Wheels in order from greatest importance to least importance for you. Put a 1 next to the item that is most important a 2 next to the second most important and so on.

Saving money

Socialization

Nutritious food

Good tasting food

Not having to cook

Having someone check in on you

How would you rate your satisfaction of the meals from Meals on Wheels?

Not at all Satisfied

not very Satisfied

Neutral

Somewhat satisfied

Very satisfied

How would you rate your satisfaction with the delivery of Meals on Wheels?

Not at all Satisfied

not very satisfied

Neutral

Somewhat satisfied

Very satisfied

How would you rate your overall satisfaction with Meals on Wheels?

Not at all Satisfied

not very Satisfied

Neutral

Somewhat Satisfied

Very Satisfied

How often do you talk with the delivery person?

Never

Rarely

About half the time

Most of the time

Every time

Typically how much time do you spend talking with the person who delivers the meal?

Do not interact with the delivery person

A few seconds

Around 1 minute

Between 1-5 minutes

Over 5 minutes

How many meal deliverers do you know by name?

None

1

2

3

4 or more

How many meal deliverers do you consider as friends?

None

1

2

3

4 or more

Would you ever ask Meals on Wheels people, either staff or volunteers, for any kind of assistance or to make referrals to any other services?

Yes

No

Have Meals on Wheels meal deliverers ever referred you to other services?

Yes

No

How would you say your diet has changed, in terms of health, since receiving Meals on Wheels?

Greatly Worsened

Somewhat Worse

No Change

Somewhat Improved

Greatly Improved

Please describe what you mean by your answer to the previous question.

How do you physically feel since receiving Meals on Wheels?

Much Worse

Somewhat Worse

No Change

Somewhat Better

Much Better

How has receiving meals affected the way you feel emotionally?

Greatly Worsened

Somewhat Worse

No Change

Somewhat Improved

Greatly Improved

Do you think receiving Meals on Wheels has improved your health?

Yes

No

Do you think receiving Meals on Wheels has contributed to your ability to continue living at home?

Yes

No

How many people live with you?

None, I live alone

1

2

3

4 or more

What is your relationship to the people who live with you? Circle all that apply

I live alone

Friends

Spouse

Children

Grandchildren

Siblings

Other:__________________

Do you have any family that lives in the same City/village as you?

Yes

No

What is your age?

Under 60

60-65

66-70

71-75

76-80

81-85

86-90

Over 90

What is your Gender? Male Female

What is your ethnicity? check all that apply

Caucasian/white

Alaskan Native/ American Indian

Asian

African American

Pacific Islander

Hispanic

Other:__________________

What is your total household income per year?

Under $15,000

$15,000-$20,000

$20,000-$25,000

$25,000-$30,000

$30,000-$35,000

$35,000-$40,000

$40,000-$45,000

Over $45,000

What is the highest level of education you have completed?

Some high school

High school graduate

Trade/technical/vocational training

Associates Degree

Bachelor’s Degree

Master’s Degree

Professional Degree

Doctorate Degree

What City do you live in?

Appendix 2: Interview questions for Juneau Clients:

24 hour recall

Food security

How long have you been receiving MOW?

Where does the rest of your food come from?

Who does your shopping?

How often do you get groceries?

How much money do you spend on food per month?

How much do you think MOW helps with finances?

Time allocation?

How is your food prepared? And by whom?

Do you know how to cook?

Are you able to cook?

How many meals per day do you eat?

Are you ever hungry and unable to satisfy that hunger?

Do you think you have enough food?

Do you consider your diet to be healthy?

Quality of life

What activities do you frequently engage in?

How many prescription medications are you on?

How much TV do you watch on a daily basis?

What is watched?

Physical health?

Chronic conditions?

Pain?

Mobility?

ability to live independently?

How often do you visit with a medical professional?

In what ways, if any, has your changing health status impacted your life?

Social life

Who do you live with?

Are there people you see daily? Who?

Are there people you see weekly? Who?

Are there people you see every month or so? Who?

Are there people that you wish you could visit with more often?

Would you like to have more social interactions?

Do you talk on the phone with people for social purposes?

Do you email people for social purposes?

Do you enjoy the interaction with MOW volunteers?

Please describe those interactions?

Do you care who delivers the meals?

Do you ever look forward to visiting with MOW volunteers?

What specifically about social interactions do you enjoy?

Describe some social interactions you have?

Social services received

What social services do you receive besides MOW? And how long have you received those services?

How do you keep in contact with these organizations?

Appendix 3: Volunteer Survey Questions:

Why did you initially begin volunteering with Meals on Wheels? Check all that apply

Friend or family suggested it

To give back to community