Foster care: motivations and challenges for foster families

Cinzia Canali, Fondazione Emanuela Zancan

Roberto Maurizio, Fondazione Emanuela Zancan

Tiziano Vecchiato, Fondazione Emanuela Zancan

The article focuses on the experience of

foster care as reported by a group of foster parents involved in a research

study in a Province of the Northern Italy. The Province, which provides foster

care services and supports the local services, carried out a research study in

collaboration with the professionals working in the local services in order to

gather original data on the foster care processes. The Province was specifically

interested in 1) analysing the campaigns for the promotion of foster care and

2) the results obtained in terms of outcomes for children involved in foster

care placements. The research study developed along two different lines: collecting

data on the campaigns promoted and implemented by the Province in the last five

years in regards to purposes, strategies, actions, and results; and

collecting data about the foster care experiences, first by analysing the

contents of individual records of children in foster care in the years

2010-2012 and then by interviewing foster families involved in foster care

placements occurred in the years 2010-2012.

The research devoted a specific focus to the characteristics of foster families and their life stories, family structure, motivations to become foster carers and their experience with children. The article considers also their perception about this experience and its impact on their everyday life. After this experience, are they willing to undergo other foster care placements? How to take advantage of their experience to further develop foster care at local level?

Foster families highlighted how they were involved in understanding the difficulties and complex stories of children and their birth families. Two main issues emerge from this focus: on the one hand the benefit for the child who experienced a foster care placement and, on the other hand, the consequences for the family involved in the foster care pathway. Families are satisfied with the foster care experience that, for many of them, was different from what they had imagined since it was more challenging, more engaging, more difficult than expected. At the same time, however, they are less satisfied as regards the role of social services. Many families are willing to experience foster care in the future provided that foster care placements have a shorter length and are more supported by services. The research highlighted the crucial role of social services in supporting foster families and the need to build new strategies for connecting the wellbeing of children, the perception of foster carers and the involvement of birth families inside a joint planning monitored over time by professionals. Such strategies are very important and need to be implemented, otherwise the number of families investing in solidarity will decrease more and more.

1

Background

Foster parents have many reasons for

fostering a child in need. Understanding why foster families are interested in

becoming carers of children in need is a crucial issue. Although in many

countries the number of children in foster care is increasing (Sebba, 2012; Del

Valle et al. 2013) also the characteristics of foster families need to be

investigated and also their feelings about the experience of family foster

care (Vanderfaeillie, Van Holen, Coussens, 2008; Schofield and Beek, 2006; Sinclair

et al., 2004). This may have an impact on the development of the placement and

may lead to underestimate the role of foster parents in this experience.

Carvalho, Delgado Pinto (2013) found that foster carers’ perspective is less positive as regards the lack of training, especially when children have developmental difficulties, the gaps in information received about the child, particularly on health stories and family life, and the uncertainty regarding the expected duration of foster care. Despite these negative aspects, most of the foster carers have a positive opinion of the experience and of its results: affection, joy of children and their development are considered the main rewards of their demanding and difficult experience. Also Blythe and colleagues (2012) highlighted how the lack of appropriate support for carers and interactions between professionals and foster parents represent a major source of dissatisfaction, which may convey negative messages to those considering fostering.

On the other hand, looking at the social work side, there is a shortage of foster carers in most countries and this may affect the process of selection and recruitment of foster families (Colton, Roberts & Williams, 2008; Thoburn, 2013: López López & del Valle, 2016). This is happening also in Italy and new strategies need to be found in order to match professional work with family characteristics and motivations (Vecchiato, 2014).

2 Foster care in Italy

The Italian law states that foster care is provided as a short-term measure when birth families are temporarily unable to care for their children. The duration of the foster care placement should be specified in the foster care decree made by the court and the placement ends when the birth family’s difficulties have been resolved or when continuation of the placement appears to jeopardise the child’s wellbeing. The responsibilities of the foster family include providing for the child’s material, emotional, social, and educational needs (both at home and school). Also, foster parents should help to maintain the links between foster children and their birth parents, unless otherwise directed by the juvenile court, and co-operate with the local social care department in working towards the child’s return to his/her birth family.

It is important to underline that the recruitment of families for foster care does not follow any national rule or standard procedures. Social and health professionals (social workers and psychologists) assess the eligibility of families. In Italy foster care is free and voluntary. It is not a paid work and foster parents usually receive a small amount of money for covering the expenses related to childcare. Social services support foster families but their involvement can vary substantially: some services meet the foster families every month, some others do it only when problems require a specific intervention.

3 Focus with foster families: contacts and questionnaire

Within this framework, the Province developed a research study on foster care placements in order to qualitatively and quantitatively investigate the data available for this population group. The Province was specifically interested in understanding the results of the campaigns promoted by its department in favour of family foster care and the outcomes of foster care placements in the previous years (Canali et al., 2013; Maurizio & Barbero Vignola, 2014). As regards this last issue, referring to the work done by Biehal (2007), Biehal et al. (2010) and Wade et al. (2011), the 2010-2012 foster care pathways were analysed and also a number of foster families were interviewed. The research study describes the characteristics of 136 children in foster care who entered in care for one or more reasons (usually more than one). In specific the most reported reasons for foster care placements are: relational problems (30.9%), deprivation (28.7%), exposure to family deviance (27.9%), and economic problems of the birth family (22.1%).

The present article focuses on the interviews of parents who experienced foster care placements between 2010 and 2012.

Within the wider research, the foster families in the Province were contacted at the end of 2013 and at the beginning of 2014. Foster families were first contacted by social workers and this contact resulted in 51 families declaring their interest in the project. These families were then contacted via email or telephone for illustrating the research, its goals and the questions that would be asked. Finally, 38 families joined the research. Some families did not adhere due to temporary difficulties, others because of the complexity of the questionnaire, others because they were no more interested in the initiative. The questionnaire for foster families consisted of two parts covering two main areas:

Part 1 - information about the foster family:

·

family composition, foster care experience and

motivations for becoming foster carers,

· influence of campaigns on their choices and relationships with local social services,

· feedback and evaluation about their foster care experience,

· impact of the foster care experience on the everyday life of the family,

· propensity for another foster care placement;

Part 2 - information about the child:

· characteristics of the child and reasons for foster care placement,

· relationship between foster family and birth family,

· difficulties experienced in the foster care placement as concerns the contacts between children and birth families.

All families were able to choose whether to fill in the questionnaire in paper or digital format. Any information collected was stored in the form of anonymous data and was only used in accordance with the purposes of the research. The analysis of data started in April 2014. Each group of variables was examined using frequency analysis. Questionnaires were treated strictly anonymously, accordingly to Italian law. The next section will focus on the information gathered from the first part of the questionnaire trying to answer the following research questions:

1. After their foster care experience, are they willing to undergo other foster care placements?

2. How to take advantage of their experience to further develop foster care at local level?

4 Family foster care pathways

The 38 families who agreed to participate in the research experienced the foster care of 70 children in their family history, corresponding on average to almost two children per family. The average duration of foster care placements was 5.5 years. Considering only foster care placements that occurred in the years 2010-2012 (involving 51 children), the majority were non-kinship placements (80.4%). Furthermore, “emergency” placements slightly prevailed over placements that were not activated in emergency situations (52% versus 48%).

Thirty of the 38 foster families (79%) received, in the period 2010-2012, only one child in foster care. Eight of them (21%) had more than one child, with these children not always belonging to the same family.

4.1 Profiles and motivations of foster families

All foster families have members of Italian nationality. Most of them are couples with children, with a clear prevalence of married couples. Couples without children represent almost 30% of all foster families in the sample.

Tab. 1 – Composition of foster families

|

|

Number |

Percentage |

|

Married couple without children |

10 |

26,3 |

|

Married couple with children |

23 |

60,5 |

|

Non-married cohabiting couple without children |

1 |

2,6 |

|

Non-married cohabiting couple with children |

1 |

2,6 |

|

Other composition |

3 |

7,9 |

|

Total |

38 |

100,0 |

Almost 70% of the families have more than twenty years of history as a couple, and only 8% less than a decade. The average age of the foster parents is around 57 years for men and 54 years for women. Furthermore, these foster families have a very high education level (around 42% with a university degree among men and 37% among women). Considering the employment situation, in about 70% of the families both parents are working. The percentage of families experiencing difficulties in their relationship or economic difficulties is around 3-5%.

Among men, the most common working positions are: office workers (5 cases), doctors (4 cases), lawyers (3 cases), non-specified workers (2 cases). Other working positions are real estate administrators, drivers, truck drivers, consultants, public officers, educators and teachers. Among women, the most common professions are teachers (7 cases) and office workers (4 cases). Other working positions include: social workers, lawyers, civil servants, accountants, cooks and others.

Overwhelmingly, these families do not belong to any permanent group or association of foster families, but half of them belongs to organized associations or movements of social commitment, in particular religious groups (47% of the families) and voluntary groups (39%).

The willingness of a family to take care of a child can result from different reasons that can be grouped in two macro categories: “general attitude”, that is a general motivation for being involved in foster care and “specific attitude” that is related to the foster care experience with a particular child. Families were asked two different sets of questions in order to grasp the “general” and “specific” motivation for foster care.

As for the “general” reasons, 47,4% of the families indicated their willingness to support other people in need and 42% highlighted their love for children. Much smaller is instead the percentage of families that considers foster care as an incentive to complete the family (5,3%) or to witness their faith or to give an educational experience to their children (8%).

Tab. 2 – “General” motivations for foster care

|

|

N of cases |

Percentage* |

|

To promote solidarity with people in need |

18 |

47,4 |

|

To witness the love for children |

16 |

42,1 |

|

To share with others their own resources |

12 |

31,6 |

|

To give a concrete sign of the family openness |

6 |

15,8 |

|

To witness that the family can give a lot |

5 |

13,2 |

|

To witness to their faith |

3 |

7,9 |

|

To educate their children to return and solidarity |

3 |

7,9 |

|

To complete the family |

2 |

5,3 |

* Percentages calculated on the total number of foster families (n=38).

As for the “specific” reasons, for about 60% of families their willingness to foster care stems from a motivation as a couple. The direct knowledge of people in difficulty (family and/or child) also plays a relevant role. About 20% of families accepted a proposal from the local social services, while 10% indicated that they had been involved because they knew other foster families.

Tab. 3 – “Specific” motivations for foster care

|

|

N of cases |

Percentage* |

|

A special motivation as a couple |

22 |

57,9 |

|

Direct knowledge of people in difficulty |

18 |

47,4 |

|

The explicit request of the services |

8 |

21,1 |

|

Knowledge of other foster families |

4 |

10,5 |

|

Previous experiences |

2 |

5,3 |

|

The desire to have children |

1 |

2,6 |

|

Readings or films |

1 |

2,6 |

* Percentages calculated on the total number of foster families (n=38).

In recent years, these families were able to observe the promotional campaigns on foster care and to participate directly in some of them. Among the families who had the opportunity to participate or directly benefit from any information and promotion initiatives on foster care, the overall assessment is positive: 88% of families consider these initiatives interesting and only a minority expresses a negative judgment.

Despite the high interest in these initiatives, the promotional activities have only partly contributed to the decision to be foster families (for more than half of the families the contribution given by these initiatives to their decision is, in fact, reduced or nil).

4.2 Connections with local services

Several questions in the questionnaire examined the professional process that led to the activation of families in foster care. The preliminary activation was very rich of events and situations in which families interacted with the different parties responsible for foster care in the local service context. Almost 8 out of 10 families had interviews with social workers and psychologists; some families only met one professional: 21% only with social workers and 13% only with psychologists.

The interviews with social workers and psychologists focussed on multiple themes (on average 5-6 contents for each family), although the information received varied greatly among families:

· about three quarters of families were informed about the life conditions of the birth families and about the interventions provided to the birth families;

· between 50-60% of the families were informed on the rights and obligations of foster families and any measures taken by the Court with respect to the birth families and children proposed for foster care;

· between 40-50% of the families were informed about previous interventions by local services in favour of the birth family and the child/children; about the foster care plan; about the health and emotional conditions of the child/children at the time of the foster care admission; about the relationship to be developed between foster family and birth family; about the estimated length of the foster care placement and the related procedures;

· less than 30% of the families were informed about the relationship of the child/children with the school or other educational services.

The lack of information by various departments about the foster care plan was highlighted also in other sections of the research. Only 42% of foster families were provided with a foster care plan with a precise time table related to the out-of-home experience of the child.

The involvement of foster families in the definition of the foster care plan occurs for two-thirds of families. Among these, the engagement mostly takes place since the beginning of the collaboration with local services.

Another important aspect is related to the participation of families in training programs: this experience involved about a third of the families (although some other families could have attended training events before 2010).

Two-thirds of the families received a proposal to participate in meetings with other foster families for mutual support and/or training, and in most cases they subsequently attended these initiatives.

4.3 The evaluation of the foster care experience

Families were asked a number of questions

in order to understand their point of view in regards to both the

overall experience and some specific aspects of foster care.

Overall, families were greatly satisfied

with the experience. They were slightly less satisfied with the relationships

with services and the support provided, and, even less, with the

experience of meeting and debating with other foster families. This last

experience was also considered not or little useful by almost half of foster

families. In details:

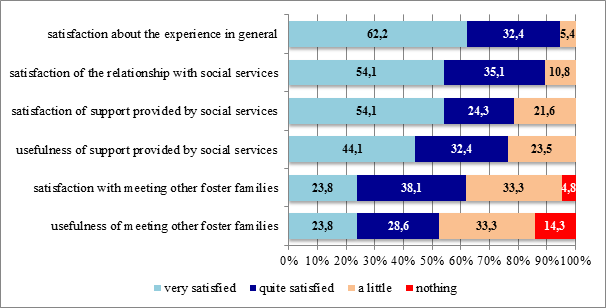

1. the overall evaluation of the foster care experience is positive, with almost two thirds of the families “very satisfied” and 32% “quite satisfied”;

2. the satisfaction of foster families with the relationship with the social services is generally positive, although the level of dissatisfaction tends to increase; in particular, nearly one fourth of the families do not consider the support provided by social services to be useful;

3. foster family satisfaction with meeting other families is not very high (almost 4 in 10 exhibit no or low satisfaction) and almost half of them attach a low level of usefulness to meeting other families.

Fig. 1 – Satisfaction and usefulness: the point of view of foster families

4.4 Impact of the experience on the family life

Another important aspect is related to the impact of foster care experience on the lives of foster families. The overall judgment is clear and almost unanimous: this experience significantly affects different aspects of family life and implies the need for a reorganisation of the family.

In particular, the main changes concern the management of daily life rhythms (this issue is expressed by almost three quarters of the families) and the organization of everyday life commitments of different family members (as indicated by 71% of families).

Less than half of the families highlight the repercussions on work, social and leisure experiences and relationships with friends. Only a third of the families indicate repercussions on the relationships with relatives and social commitments.

Tab. 4 – Aspects of family life that are affected by the foster care experience

|

|

N of cases |

Percentage* |

|

Rhythms of daily life |

28 |

73,7 |

|

Organization of commitments of different family members |

27 |

71,1 |

|

Work commitments |

16 |

42,1 |

|

Socializing and entertainment experiences |

15 |

39,5 |

|

Relationship with friends |

15 |

39,5 |

|

Social commitment |

13 |

34,2 |

|

Relationship with family members |

12 |

31,6 |

* Percentages calculated on the total number of foster families (n=38).

The experience of foster care affects all the members of foster families, including children, if present. All families bear this out, highlighting both positive and critical aspects. In particular, the effects that foster families noticed in their children may be positive or negative.

Among the positive aspects, it is possible to highlight cultural aspects ("commitment towards social engagement and solidarity", "knowledge of a social reality that was unknown") but, also, attitudes ("openness to others", "sharing", "development of a sense of responsibility") and a contribution to the construction of the individual identity of children ("acquisition of a normal view of themselves"). Critical aspects are the existence of unexpected emotions (implicitly considered as not appropriate) such as jealousy, or the emergence of difficult situations (especially with adolescent children), and more in general, the feeling of having forced children to live in a family environment that is less calm and quiet than usual and in which - among other things - the child can experience a reduction in his/her privacy.

The experience of foster care in its ordinary and daily development offered to a large number of families (44%) more than they had previously imagined, while the percentage of those who received less than they had thought is less than 20%.

Many comments concern the relationship with the child in foster care and what this relationship implied for the family. Although some critical aspects emerge (more fatigue, more limitations and complexity in managing situations, more energy absorbed in dealing with child problems and needs) several positive consequences result from this experience: greater emotional involvement, increased responsibilities, emotional bond with the child, richer dialogues, higher satisfaction and gratification. A couple of families reported that an important element is represented by the length of foster care that – in their case – was longer than expected/agreed.

A few families highlighted the issue of the relationship with the child's birth family, which they initially feared but, unexpectedly, it turned out to be an opportunity not only of committing to caring for the child, but also of getting useful stimuli to grow and improve as a family. Critical aspects are related to the contribution of local social services: foster families were expecting a more continuous support in line with a better-defined plan, but much was left to the personal skills of the foster family members.

Most families shared the foster care situation within their family network (84%) and, even more, their friends (96%) and the associations to which they belong (97%).

4.5 Towards other experiences of foster care

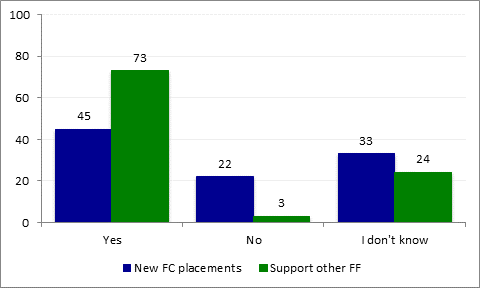

Despite the positive judgement about the

foster care experience, only 44% of the families report they would engage in

further foster care experiences. A third of the families are unable to give a

specific answer and 22% declares they would not engage in other foster

care experiences.

The positive judgment on their experience, however, could lead these foster families to invite other families to join the experience (73%). These messages from the foster families confirm the complexity of the foster care experience.

Fig. 2 - Towards other experiences of foster care: orientation to new foster care placements (FC) and willingness to support other foster families (FF) (percentage values)

Among the families that exclude their future willingness to engage in other foster care placements, there are two different reasons: on the one hand, the need to be not too old for growing a child and, on the other hand, the emotional and psychological impact that this experience implies and its impacts in terms of family balance, motivation and strength needed to handle the family dynamics.

Some families do not exclude a new

involvement in foster care but only if certain conditions are agreed, for

example the definition of a foster care plan. The words of families are, in

this sense, very clear. They would like a well-defined plan, with greater

autonomy within the framework defined by social services with a greater

collaboration and information sharing. Also, they express propensity for foster

care placement of children who are waiting for adoption or other foster care or

shorter plans with clearer goals.

Some families believe that they still have the enthusiasm and willingness to live this experience again, even if they recognize its complexity and the efforts needed. Overall these families express a positive evaluation of the foster care experience and its return in terms of reciprocity.

The different arguments that foster families offer as a stimulus for other families to invest in foster care can be synthesised as follows:

· a group of arguments highlights the intertwining benefits for both the child in foster care and the foster family. In particular, there is a strong belief that the child in the new foster family can find self-confidence and trust and can be enriched and strengthened;

· a second group focuses the attention exclusively on the outcomes for the child and the birth family. Specifically, the emphasis is on the idea that foster care can support the child and help solve the problems of the birth family, through an act of love;

· a third group of arguments focuses on the benefits for the foster family itself, with the emphasis on foster care as an experience that is meaningful, that enriches the couple and also every family member, leading to a higher awareness of the family history and situation, that gives more than the energies and efforts it requires;

· a fourth group, lastly, emphasizes the complexity of the path that leads a family to become a foster family and the difficulties to encourage others to invest in this perspective. In order to get to this decision, a large inner work is necessary that involves the individual and the couple, great strength and emotional commitment, a psychological and physical commitment to facing the stress that foster care generates and the involvement of the family network for support. The awareness of all these issues makes it difficult for some foster families to suggest it to other (potential foster) families.

Box 1 –Reasons* to suggest this experience to other families

|

- It enriches us and returns to the child a bit of trust in adults, in the family, in themselves. - It is a wonderful experience; solidarity gives meaning to so many situations. - It is a way to be useful to others. - It's an experience that has enabled us to receive more than what we gave. - It is a complex experience, but - if planned and monitored - it is positive for all those who are involved. - It is a strong experience of life that has an impact on the couple and the individual. - Foster care is potentially an extraordinary tool for supporting the child and, where possible, the birth family. - The experience had some painful and grey aspects, but it was also very enriching. - We believe that we have been particularly lucky, we also believe that every foster care experience is a story in itself, and that personal motivations are very important. For us and for our family this foster care was a real blessing. - For the children. |

(*) Our translation from Italian.

5 Discussion

Foster carers highlighted how families have been involved in understanding the difficult and complex stories of children. There are two main issues that emerge: on the one hand the benefits for the child and, on the other hand, the consequences for the family involved in the foster care pathway.

As regards the first issue, foster families fully agree with the professionals interviewed in the same research project on the problematic nature of children and birth families’ situations. Foster carers express a positive view about the impact of the experience of foster care for the child wellbeing. This is in tune with other research in different countries (Sebba, 2012). Families feel that they met the needs of the child, even if they know that this does not always coincide with an adequate support to the needs of the birth family. This could be related to the feelings of bereavement, sadness, grief and anger that the birth families could have towards the separation and this relationship between families could therefore be difficult to accept (Schofield and Stevenson, 2009; Neil et al, 2010; Del Valle et al., 2013; Maurizio & Barbero Vignola, 2014). Foster families highlighted the important relationship with the child: the child in foster care feels as part of the family, experiencing a feeling of trust towards the foster family that encourages the child. In line with the research about the sense of belonging of fostered children towards their substitute families (Biehal, 2012), the families recognise the critical aspects related to the contacts with birth parents and the difficulty to implement the reunification plan. At the same time, they underline that the foster care experience allowed the children to build/develop greater confidence in themselves and in their birth families, strengthening and developing useful skills for the reunification process or the independent living process.

In the study, foster families also highlight how much this experience has implied in terms of engagement and change. Not only the family rhythms and routines but also the self-representations - as a family - and the parenting stories have changed. This occurs not at the end of the foster care placement, but during the experience and it affects adults but also children. In any family, the experience of a family member necessarily influences all the others. This happens also in foster care - as the foster families stated - where the child is not a “guest” but part of the family, although for a (long) period. The research, in line with recent studies, also highlights the involvement of foster carers’ children in the care process and the impact of fostering on their lives (De Maeyer et al., 2014; Höjer et al., 2013; Schofield et al., 2012; 2013; Rodger et al. 2006).

In this framework, it is important to take into account the perceptions of families: they are very satisfied with the experience that, for many of them, was different from what they had imagined: more challenging, more engaging, more difficult than expected. At the same time, however, they express a global assessment that is less positive as regards the role of social services. A part of this dissatisfaction certainly derives from the fact that at least 90% of the foster care placements (from the point of view of the families) began with a view to reunification but only in a tenth of the cases this really happened. Another aspect that contributes to the partial satisfaction is represented by some shortcomings in procedures, planning and information. An important percentage of families reported that they lacked information and they were partially involved in the foster care plan. A third element is the unsatisfactory support provided during the relationships with the birth family. Many families are still showing willingness to engage in foster care experiences in the future (those who express themselves differently identify mainly practical reasons, such as aging) provided that the foster care placements have a shorter length and receive greater support by the services.

6 Conclusion

The findings related to the point of view of foster families as regards their experience is particularly important for improving foster care. For its exploratory nature, there are various limitations related to the generalisability of the results but they highlight some issues that can be very interesting for the local and national approach to foster care.

Results highlight the crucial role of services in supporting foster families and the need to build new strategies for connecting the wellbeing of children, the viewpoint of foster carers and the involvement of birth families within a joint planning to be monitored over time by the social services. This need for integration is not always clear to professionals and policy makers, which causes the fragmentation of responsibilities among different people and services.

A call for a more

integrated system can be therefore recognised in the findings of the research.

This requires a specific attention to the issue of “sharing responsibility”:

what activities are most useful for the child, the birth family, the foster

family? Are these activities and their outcomes monitored and evaluated? In

particular, has the challenge of assessing outcomes for the child been tackled?

It seems that a “gravitational centre” is missing: as the child becomes the centre of gravity inside the universe of responsibilities, everything becomes clear. In such a universe, planets have a real source of light and strength (foster family, birth family, social services…). Through their rotation (i.e. coordination and integration) they jointly contribute to delineating the concurrent fields of forces. In this vision, they can turn from being satellites and recipients to becoming active and responsible sources of a destiny that involves parents and children, the community of foster parents, parents and children, inside their life spaces.

The focus of the article on foster carers provided relevant indications about their motivations, the impact of this experience on their life, their willingness to continue this experience, their connections with social services and the challenges they had to face. These findings are useful for further development of foster care, especially at a time of increased fragility among families. In this framework, also researchers are required to better explore these perspectives and build innovative ways for involving both professionals and families.

References

Biehal N. (2007). Reuniting Looked After Children with their Families: Reconsidering the evidence on timing, contact and outcomes. British Journal of Social Work, 37, pp. 807-823.

Biehal N. (2012). A Sense of Belonging: Meanings of Family and Home in Long-Term Foster Care. British Journal of Social Work, Advance access published November 25, 2012, DOI: 10.1093/bjsw/bcs177.

Biehal N., Ellison S., Baker C. & Sinclair I., (2010). Belonging and Permanence: Outcomes in Long Term Foster Care and Adoption. London: BAAF.

Blythe, S. L., Halcomb, E. J., Wilkes, L., & Jackson, D. (2012). Perceptions of Long-Term Female Foster-Carers: I’m Not a Carer, I’m a Mother. British Journal of Social Work, pp. 1–17.

Canali C. & Vecchiato T. (eds.) (2013). Foster care in Europe: what do we know about outcomes and evidence? Padova: Fondazione Zancan.

Canali C., Maurizio R. & Biehal N. (2013). Making the right decision: A comparison between professionals approaches. In Canali C., Vecchiato T. (eds), Foster care in Europe: what do we know about outcomes and evidence? Padova: Fondazione Zancan, pp. 50-54.

Carvalho, J., Delgado P. & Pinto V.S. (2013). Evolution of foster care in Portugal: Perspectives of foster children and carers. In Canali C., Vecchiato T. (eds), Foster care in Europe: What do we know about outcomes and evidence? Padova: Fondazione Zancan, pp. 73-76.

Colton, M., Roberts, S. & Williams, M. (2008). The Recruitment and Retention of Family Foster-Carers: An International and Cross-Cultural Analysis. British Journal of Social Work 38 (5): 865-884.

Delgado P. (ed.) (2016). O contacto no acolhimento familiar: O que pensam as crianças, as familias e os profissionalis. Porto: Mais Leitura.

Del Valle J.F., Canali C., Bravo A. & Vecchiato T. (2013). Child protection in Italy and Spain: Influence of the family supported society. Psychological Intervention, Vol. 22 (3), pp. 227-238.

De Maeyer, S., Vanderfaeillie, J., Vanschoonlandt, F., Robberechts M., & Van Holen F. (2014). Motivation for foster care. Children and Youth Services Review, vol. 36, issue C, pages 143-149.

Höjer I., Sebba J. & Luke N. (2013). The impact of fostering on foster carers’ children: An International Literature Review. Rees Centre, University of Oxford.

López López, M. & del Valle, J.F. (2016). Foster carer experience in Spain: Analysis of the vulnerabilities of a permanent model. Psicothema, Vol. 28, 2, pp. 122-129.

Maurizio R. & Barbero Vignola G. (2014). L’affidamento familiare in provincia di Piacenza, Research Report. Piacenza: Provincia di Piacenza.

Neil E., Cossar. J., Lorgelly P. & Young J. (2010). Helping Birth Families: Services, costs and outcomes. London: BAAF.

Rodger, S., Cummings, A., and Leschied, A.W. (2006). Who is Caring for Our Most Vulnerable Children? The Motivation to Foster in Child Welfare. Child Abuse and Neglect 30, 1129-1142.

Schofield, G. & Beek, M. (2006). Attachment Handbook for Foster Care and Adoption. London: BAAF.

Schofield G. & Stevenson O. (2009). Contact and Relationships between Fostered Children and their Birth Families. In Schofield G., Simmonds J. (eds), The Child Placement Handbook: Research, policy and practice, London: BAAF, pp. 178-202.

Schofield G., Beek M. & Ward E. (2012). Part of the Family: Care Planning for Permanence. Foster Care. Children and Youth Services Review, 34, pp. 244-253.

Schofield, G., Beek, M., Ward, E. & Biggart, L. (2013). Professional foster carer and committed parent: role conflict and role enrichment at the interface between work and family in long-term foster care. Child and Family Social Work, 18, pp. 46-56.

Sebba, J. (2012). Why do people become foster carers? An International Literature Review on the Motivation to Foster. Oxford: Rees Centre.

Sinclair, I., Gibbs, I. & Wilson, K. (2004). Foster Carers. Why They Stay and Why They Leave. Jessica Kingsley Publishers, London.

Thoburn, J. (2013). Services for vulnerable and maltreated children, in Wolfe, I. and McKee, M. (eds.) (in press) Children’s Health Services and Systems: A European Perspective. Milton Keynes: Open University Press, pp. 219-238.

Vanderfaeillie, J., Van Holen, F. & Coussens, S. (2008), Why do foster care placements break down? A study on factors influencing foster care placement breakdown in Flanders. International Journal of Child & Family Welfare 2008/2-3, page 77-87.

Vecchiato T. (2014). Sfide per il futuro. In: I diritti dell'infanzia e della famiglia da proteggere e promuovere. Monograph Studi Zancan 2, pp. 85-86.

Wade J., Biehal N., Farrelly N. & Sinclair I. (2011). Caring for abused and neglected children. Making the right decision for reunification or long-term foster care. London and Philadelphia: Jessica Kingsley Publisher.

Author’s Address:

Cinzia Canali

Fondazione Emanuela

Zancan onlus

Via Vescovado, 66

35141 Padova

(Italy)

www.fondazionezancan.it

Corresponding

author: cinziacanali@fondazionezancan.it

Roberto Maurizio

Fondazione Emanuela

Zancan onlus

Via Vescovado, 66

35141 Padova

(Italy)

www.fondazionezancan.it

Corresponding

author: cinziacanali@fondazionezancan.it

Tiziano Vecchiato

Fondazione Emanuela

Zancan onlus

Via Vescovado, 66

35141 Padova

(Italy)

www.fondazionezancan.it

Corresponding

author: cinziacanali@fondazionezancan.it