Disconnected Youth? Social Exclusion, the ‘Underclass’ & Economic Marginality

Summary

Most young people in the UK make relatively ‘successful’, unproblematic transitions from school to work and adulthood. What do we call those that do not? Labels imply explanation, not just description. Terms with academic and policy currency tend to define such young people by something they are not or by their presumed social and economic distance and dislocation from ‘the rest’. How we might best describe, explain and label the experience and problem of so-called ‘socially excluded’, ‘disconnected youth’ is the focus of the paper.

It draws upon extensive qualitative research with young adults growing up in some of Britain’s poorest neighbourhoods, looking particularly at their labour market transitions. Some of the problems and inaccuracies of underclass theory and orthodox conceptualisations of social exclusion are discussed in the light of empirical findings. Following CW Mills, the youthful biographies described are set in a wider panorama of social structure and economic opportunity, particularly the rapid de-industrialisation of the locality studied. Understanding these historical processes of socio-economic change leads to the conclusion that, in short hand, ‘the economically marginal’ is the best descriptive label of the research participants and ‘economic marginalisation’ is the best explanation of their condition.

Introduction

Most young people in the UK make relatively ‘successful’, unproblematic transitions from school to work and adulthood (albeit that they can last longer and be more circuitous than in previous decades; Furlong and Cartmel 2007). What do we call those that do not? How do we describe those who, for instance, experience recurrent periods of unemployment and poor quality employment? A plethora of normative labels are ready to hand and enjoy widespread currency in policy and academic discourse in the UK: the ‘disaffected’, ‘disengaged’ and ‘disconnected’, the ‘hard to reach’ and ‘the hard to help’, ‘the socially excluded’, ‘the youth underclass’ and, of late, ‘NEET’ (i.e. those ‘not in education, employment and training’). Names matter. Representations of youth are ‘overburdened’ with unspoken but powerful assumptions (Ball et al. 2000). Labels carry implied explanations, not just descriptions with those listed here defining young people by something they are not, something that they do not have or, generally, their presumed social and economic distance and dislocation from ‘the rest’. ‘Deficit models’ that focus attention on the supply-side of the labour market - on what aspirant young workers lack - have a long history in UK policy (with the absence of sufficient aspiration being a common theme currently) (Mizen 2003; Pohl and Walther 2007). How we might best describe, explain and label the experience and problem of so-called ‘disconnected youth’ provides the motivation for this discussion.

Studying ‘disconnected youth’

The Research Site & Studies

Since the 1990s, the Youth Research Group [1] at the University of Teesside has undertaken extensive research into the life transitions of young adults from some of Britain’s poorest neighbourhoods; in Teesside, North East England. This is a conurbation that has undergone remarkably speedy economic change. Famous for its industrial prowess and economic success in steel, chemical and heavy engineering industries in the post-war, Fordist period of full-employment, by the end of the 20th century it had become ‘one of the most in de-industrialised locales in the UK’ (Byrne 1999: 93).

Our first two studies - Snakes and Ladders (Johnston et al 2000) and Disconnected Youth? Growing up in Britain’s Poor Neighbourhoods (MacDonald and Marsh 2005) – conducted fieldwork between 1998 and 2001. They investigated youth transitions in a context of severe socio-economic deprivation; in Teesside wards that were in the top five per cent most deprived nationally (with some ranked amongst the five most deprived wards, from 8,414, in the country; DETR 2000). Both studies involved periods of participant observation with young people and interviews with professionals who worked with young people or the problems of poor neighbourhoods (e.g. youth workers, employment services staff staff, drugs workers).

Sample

At their core, though, they relied on lengthy, detailed, tape-recorded, biographical interviews (Chamberlayne et al. 2002) with 186 young people (82 females and 104 males) aged 15 to 25 years from the predominantly white, (ex)manual working-class population resident here. Our third project, Poor Transitions (Webster et al. 2004), followed the fortunes of a proportion of the earlier sample (34 people from 186, 18 females and 16 males) as they reached their mid-to-late twenties, in 2003. In each study, sample recruitment was purposive and theoretically oriented toward capturing as diverse a set of experiences of youth transition as possible. One label attached to such people in the research and policy literature is ‘hard to reach’ (Merton 1998). Our experience was that with determination (in tracking down the different ‘sorts’ of interviewees we wanted), flexibility (in the timing and location of interview opportunities), honesty (in terms of the aims, motives and likely outcomes of the research) it was not hard to reach this group of young adults, nor to hold detailed, lengthy, candid interviews with them. It is the powerful, not the powerless, who are most hard to access for research. This paper draws upon the researched completed for all three projects.

Searching for ‘the Underclass’, Researching ‘Social Exclusion’

One theoretical spur to the research came from the writings of the American, neo-liberal political scientist, Charles Murray – the champion of cultural or conservative theories of the underclass in the US and, later, in the UK (1990, 1994). His underclass theory was at once influential (in political circles on both sides of the Atlantic) and controversial. Few British social scientists were prepared to engage empirically with his theorisation of the alleged emergence of a culturally distinct, morally reprehensible, structurally separate underclass; the ‘other kind of poor people’ (Murray 1990: 17) seduced by generous social welfare regimes into criminal, indolent, welfare dependent, anti-social lifestyles. Murray (1994) cited Middlesbrough (Teesside’s main town) as a prime locale for the location of this ‘new rabble underclass’ because it displayed high rates of crime, unemployment and births outside of marriage concentrated in one place; his classic ‘early warning signals’ of the arrival of the underclass. The convenience of research on our doorstep was obviously an attraction. More important explanations for why we chose to investigate Murray’s ideas when most British social scientists stopped at critique were that, in our view, the sort of socio-cultural class development he proposed was at least feasible in principle (Roberts 1997, 2000) and extant empirical research that claimed to disprove his thesis was methodologically unsuited to that task (see MacDonald 1997).

Thus, we tested Murray’s thesis using methods, in a place and amongst people most likely to reveal the underclass. Of course, the overt influence of underclass theory has declined since the 1990s and, particularly as a result of the election of ‘New Labour’ governments since 1997, ‘social exclusion’ has become a more fashionable, widely used and apparently less controversial term in the UK for summing up the range of social problems said to typify the residents of multiply deprived neighbourhoods (SEU 1998; Byrne 1999). Understanding the extent to which young people in our research site really were disconnected from the social, economic and moral mainstream - or whether the concept and language of ‘social exclusion’ and ‘the underclass’ was disconnected from their lives and experiences - was thus the major aim of the research.

Analysing youth transitions

There is not space here to debate arguments about the appropriateness of metaphors such as ‘transition’ in a period when the meanings of life-course categories such as ‘youth’ and ‘adulthood’, and the boundaries between them, are increasingly blurred (see Jeffs and Smith 1998; MacDonald et al. 2001). Suffice to say that we believe that employing some sort of view of - and term for - processes of biographical change experienced in the years following compulsory school leaving age (16 in the UK) remains critical to any meaningful sociological study of ‘youth’ and advantageous to comprehending broader processes of social change and continuity.

In simple terms youth transitions can be understood as the pathways that young people make as they leave school and encounter different labour market, housing and family situations as they progress towards adulthood (Coles 1995). Our approach regards an individual young person’s transition as the outcome of individual agency informed by local sub-cultural and class cultural values and constrained by the contingencies of social structural opportunities. Our studies have so far focussed on six aspects or ‘careers’ within a person’s transition: ‘school-to-work’ (e.g. experiences of training, jobs, unemployment); family (e.g. becoming a parent, partnerships); housing (e.g. leaving home, independent living); leisure (e.g. changing peer associations, identities); criminal (e.g. offending, desistance); and drug-using careers (e.g. the movement from ‘recreational’ to ‘dependent’ drug use). No presumption is meant about the content, nature or direction of these careers or of an overall transition – these are empirical questions for study. Young adults’ ‘school to work’, labour market transitions are the focus of this paper.

Analysis of transcripts gathered from 186 interviews with young people involved standard, ‘cross-sectional’ comparison of each and every case by key themes and questions. It also involved a less common process of ‘vertical’, longitudinal and quasi-longitudinal (because these were biographically focussed interviews) analysis of each individual’s transition (e.g. that examined the interdependent effects of different careers and of ‘critical moments’ in young people’s lives).

Labour market transitions: research findings

Plus ça change… school and after

Willis’s classic Learning to Labour (1977) stressed the cultural correspondence between working-class experience of school and of post-school factory life. He was rightly criticised for presenting an overly simplistic theorisation of the range of educational orientations possible amongst working-class youth (see Brown 1987). His ethnography of how traditional, class and gender-segregated employment ‘lured’ working-class lads into working-class jobs did, however, seem to capture the acculturated predilection for ‘real work’ for ‘real men’ amongst some working-class young people. The decline in these forms of employment in the 1980s and ‘90s led O’Donnell and Sharpe (2000: 45) to predict the disappearance of the ‘cocksure attitude to job prospects of the lads of Willis’s study’.

According to our research, however, this class-based orientation to ‘real work’ (over abstract, academic learning) is more resilient; Willis’s ethnographic description of school disaffection, based on research from thirty years ago, still captured nicely the experience of many of our participants. The opportunity for easy progress to working-class jobs, of the sort traditional to Teesside, had all but disappeared by the time of our study yet interviews underlined how long-standing processes of working-class educational ‘underachievement’ continued (see MacDonald and Marsh 2005). Thus, interviewees described: ‘not being bothered with’ by schools more focused on those closer to A-C grades at GCSE; poor quality provision for ‘us in the lower classes’; their own rejection of the relevance and rationale of formal education (particularly the meritocratic claim that better qualifications meant better job prospects); and how powerful peer groups disrupted educational practices. The stubborn resistance to formal, academic schooling and the continued failure of an educational system to capture the commitment of many working-class young people is a crucial first step in explaining the overall and shared experiences of this group after school, as we will see.

Interviewees left school very poorly qualified. Their next steps took them to post-compulsory, low level, low quality, training & educational courses (often unfinished); low/ no skill, poorly paid manual or service sector jobs, or the status now described as ‘NEET’ and previously known as ‘unemployed’.

Informants’ post-school labour market careers certainly contained much experience of unemployment – as Murray’s depiction of the young underclass claims. Worklessness was a common and recurrent experience for virtually all interviewees. But so was employment. Now, this is a simple but crucial finding vis-à-vis underclass theory and conceptualisations of social exclusion. Post-school transitions, from 16 to 25 years, were typified by their instability, insecurity, circularity and lack of progression. A typical sketch would see school leaving at age 16 followed by a youth training scheme, then a job, then unemployment, a further education course, unemployment, a New Deal for Young People programme (a government scheme for the young unemployed), a job, unemployment, another New Deal programme and so on.

Even from this sketch we have a hint of the problems of a theory of the youth underclass that posits voluntary idleness underpinning a fixed stock of welfare dependent young adults (as Murray’s does). Neither does this sketch of intermittent participation in education, employment and training sit easily with policy approaches that emphasise the non-participation of socially excluded, ‘NEET’ young people. Thus, we do not paint a picture of economic exclusion but of economic marginality wherein poorly qualified, working-class young adults churn between the post-16 market of ‘options’ available to them. The flaws in these dominant representations come more fully to view when we hear the views and experiences of the people to whom we talked.

On not being a ‘dole wallah’ [2]

Unemployment has blighted the neighbourhoods we studied for decades. Even those who would eschew the moral castigation of Murray’s approach might allow for the possibility that here, if anywhere, working-class residents might have found ways of emotionally accommodating to lives lived with unemployment. We scrutinised the 186 interview transcripts for favourable commentaries about being unemployed or at least some acceptance of life ‘on the dole’. We identified only four interview snippets of this sort. All four referred to very short periods (of days to a few weeks) in which joblessness was treated as a novel, holiday-like, temporary relief from the demands of a job. Overwhelmingly, we uncovered an insistent valuing of work as a source not just of income but of self and family respect: old-fashioned, ‘respectable’ working-class views about the importance of working for a living, of self-reliance and of stigma against those perceived to be work-shy.

We heard these viewpoints from some unlikely quarters. Malcolm, 19, had earlier been excluded from school, had no academic qualifications, had been frequently unemployed and had convictions for house burglary. We suspect he is exactly the sort of young man that Murray would elect for underclass membership. Admittedly, Malcolm was the most vociferous and eloquent in his rejection of what he regarded as ‘welfare dependency’ but his views were common ones:

“I would hate being on the dole…I won’t do it. It’s embarrassing going to the Post Office with your giro. You just become lazy, have a lazy life… I just don’t wanna sign on the dole. I wanna work…It’s a weekly wage for a start, instead of a daft £78 per fortnight. It’s just part of life. To have a job and support your family. So instead of him [his son] growing up and when his friends’ Mams or teachers say ‘what does your Dad do?’ ‘Oh, he’s on the dole’. I don’t want none of that. I want him to grow up and say ‘Oh, our Dad’s working at summat’. So he can feel proud and have nice things when he gets older.”

Interviewees sometimes laughed, literally, at the notion that because their parents had been unemployed that they had learned that a life of unemployment was acceptable. Conversely, the poverty and joblessness of parents spurred young adults to avoid the same for themselves. Thus, like Malcolm above, they neatly reversed the role model effect that Murray says lies at the root of the inter-generational transmission of underclass values (and, as a consequence, Malcolm refused to claim benefits to which he was entitled, reducing his family to pronounced material hardship).

Confusingly, however, when the key tenets of Murray’s theory were put to interviewees they were met with wide agreement. Depressing, graphic accounts of their own, individual episodes of worklessness contrasted with victim-blaming, cultural theories of unemployment in which personal predilections were given centre-stage: ‘I want to work, they are lazy’. The harshest critics of ‘dole wallahs’ were themselves unemployed. Murray’s account of the British underclass has the sparsest of evidence (1990, 1994). In a few, brief conversations with residents in areas of high unemployment he heard exactly the same sort of denunciation of the local unemployed as work-shy and welfare dependent, using this as grounded, common-sense fact to set against the wrong-headed thinking of out-of-touch, liberal intellectuals. Unlike him, however, we understand this ‘dole-wallah discourse’ not as realistic depiction of what is but as part of a complicated local mythology that sought to defend individual and family reputations by echoing, but excluding oneself from, widely-held, often-heard tirades against benefit claimants. Insecure personal and family ‘respectability’ is shored up by castigating others in the same objective situation. Stigma still attaches to unemployment. Kelvin and Jarrett (1985: 123), summarising psychological research on the self-identity of unemployed people, could be describing Malcolm in the following observation: he feels tainted by association, he believes others associate him with these ‘inadequates’, as indeed they often do…//…he may have more need than many for social comparisons which enhance his self-esteem…//…to feel that he is better than others who are in the same position.

‘Poor Work’

So, on one side of the coin we found a vehement opposition to a living a life on welfare and on the other an almost ‘hyper-conventional’ valuing of work. Nuña Murad found a similar class-based ‘work ethic & enthusiasm for work’ amongst excluded groups in continental Europe, describing ‘its persistence in current times [as] remarkable’ (2002: 98). This cultural attachment to work helps explain the chaos and churn of post-school transitions. Government training programmes and further educational courses were typically perceived by young adults as ‘second best’ to a job – and unlikely to lead to one (a viewpoint confirmed by our tracking of work histories). They entered the bottom of end of a quality stratified market of post-16 programmes which carried little labour market dividend (Furlong 1992) and would abandon schemes if the chance of a ‘real job’ arose. Subsequent to the deindustrialisation of the local labour market and the decimation of better quality routes for working-class young people (for instance via apprenticeships in skilled, manual work), ‘real jobs’ for these interviewees now tended to come in the form of ‘poor work’ (McKnight 2002).

The labour market for interviewees was comprised primarily of low/ no skilled, low paid manual and service sector employment. They got jobs as operatives in food-processing and textile factories, bar/ fast food staff, care assistants, security guards, labourers and shop assistants. A defining feature of this employment was its casualisation and insecurity (Felstead and Jewson 1999). Contrary to policy and academic pronouncements about the coming of a new, information economy in which skill and qualification are paramount and opportunities for unskilled work dissipate, informants were easily hired into, and fired from, the abundant ‘poor work’ at the bottom of the labour market (Green and Owen 2006). It was work that asked employees mainly for their physical presence (rather than skills, qualifications or experience) and which offered little protection or permanence. Losing jobs was discussed in tones of the ‘taken for granted’ even when instances of unfair, exploitative and illegal treatment were described.

Quintini et al argue that employment insecurity and the movement of young workers between jobs is ‘just part of the natural dynamics of settling into the world of work’:

“Unsurprisingly, youth represent a high proportion of new hires and job changers [and job quits]…youth tend to change jobs more frequently at the beginning of their career in search for the best possible match between their skills and those required by employers” (2007: 7).

We are sceptical of this orthodox depiction of insecure, early labour market careers as being primarily choice-driven, ‘natural’ and passing – at least in respect of socially disadvantaged young people. There is, however, little extant, contemporary research that has tracked the longer term employment careers, particularly of those carrying labour market disadvantages and which therefore is able to properly test this view (MacDonald 2009) [3] . Some survey research does suggest that ‘fragmented’, insecure employment histories can be a lasting phenomena for some working-class young people (Furlong and Cartmel 2004; Fenton and Dermott 2006). The journalist Polly Toynbee (2003: 5-6) puts it like this:

“Low pay is fair enough if these jobs can be labelled ‘entry level’, just a first step on the ladder…but very few move far, few make it to the next step. They inhabit a cycle of no pay/ low pay insecurity. This indeed is the end of social progress.”

This exactly confirms what was uncovered in our Poor Transitions study (Webster et al. 2004) in which we followed up interviewees as they reached their mid to late twenties. At the age of 27, young adults were working in the same forms of employment as they had done at the age of 17 years. ‘Poor work’ was a lasting condition; it entrapped interviewees at the bottom of the labour market, ensuring their lasting poverty and economic marginality and signalling their downward social mobility to the bottom of the class structure [4] .

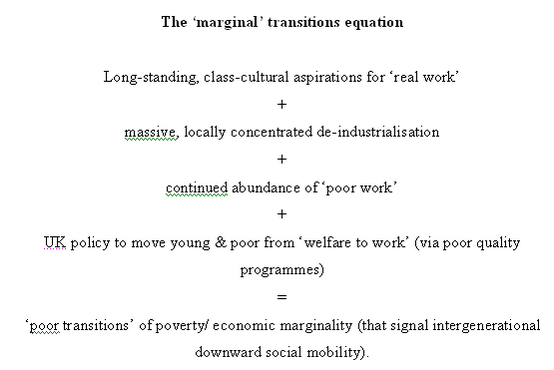

As summary of our findings, we provide the following sketch:

Conclusion

What does this brief review of our studies’ findings tell us about the connection of underclass theory to the lives reported? How much better are the concepts and labels of the social exclusion discourse?

Many flaws in underclass theory are highlighted by our research (see MacDonald and Marsh 2001, 2005) but selected here is just one element: its over emphasis of individual choice and under emphasis of social constraint. These young adults chose to work, rather than to remain idle as Murray asserts. This choice, however, was constrained drastically by the sheer lack of opportunity for better work and the proliferation of ‘poor work’. Marx’s famous dictum holds that ‘men make their history, but they do not make it as they please…under self-selected circumstances’ (1852). One interviewee (Simon, 24 - whom we suspect had not read Marx) articulated the same from his viewpoint: ‘I try to make the best out of the choices available but I have no control over what choices are available…so it’s a mixture, I control my own destiny to a certain degree’. The limits on choice and control were numerous and included the multiple hardships and deprivations that bear down on those who grow up in England’s poorest neighbourhoods. To borrow CW Mills’ phrases, the interviews we gathered were filled with the ‘public issues’ of an unequal social structure that percolated down into, and interviewees typically perceived only as, ‘personal troubles’ of individual biography: of failing at school; of poor quality post-16 schemes, programmes and employment; of unemployment; of lasting personal and family poverty; of drug dependency; of criminal victimisation (and offending); of ill-health and the death of loved ones.

One facet of ‘weak’ conceptualisations of ‘social exclusion’ (Byrne 1999), shared with underclass theory, is a tendency to see – and explain – social exclusion in terms of the characteristics of individuals or places. Thus, the often quoted definition of the Social Exclusion Unit (SEU 1998: 1) describes it as: ‘…a shorthand label for what can happen when individuals or areas suffer from a combination of linked problems such as unemployment, poor skills, low incomes, poor housing, high crime environments, bad health and family breakdown’. By this definition, our research sites and samples could undoubtedly be classed as ‘socially excluded’.

More sophisticated, sociological treatments identify social exclusion as lack of participation in ‘three important spheres of daily life which can trap people in processes of social exclusion: [the] economic, political and cultural’ (Cars et al. 1998: 280). ‘Cultural’ is sometimes referred to as ‘the social’, to include measures of social support, social contact and so on. In this sense, only in terms of lack of political participation could our samples be regarded as ‘socially excluded’ [5] . The neighbourhoods and people we studied were relatively rich in terms of supportive social networks of family and friends and bonding social capital. Subjectively, informants stressed their strong sense of place attachment, of community and of social inclusion, not exclusion. Informants came from – and were included in - a locally embedded, mono-cultural, relatively stable white, working-community [6] .

Critically, this community and its younger members were not economically excluded in any literal sense. Near permanent, structural excision from the labour market and, for some theorists, accompanying cultural preferences for ‘benefit dependency’ are the defining features of social exclusion and/ or underclass membership. As the title of his seminal text When Work Disappears (1996) suggests, W.J. Wilson sees the collapse of the labour market as pre-eminent amongst the factors implicated in the creation of the poor, US ghetto. He says (1996: 52-53) that young people:

“lose their feeling of connectedness to work in the formal economy …//…they may grow up in an environment that lacks the idea of work as a central experience of adult life – they have little or no labor force attachment…//…[those] who maintain a connection with the formal labour market - that is, those who continue to be employed mostly in low-wage jobs – are, in effect, working against all odds.”

Compare this quotation with that from Malcolm, earlier. Work has not disappeared in Teesside and what Wilson describes as untypical was typical in our study: i.e., the continued attachment of people to work and connection to (low wage) employment.

‘Stronger’ theorisations of ‘social exclusion’ ask who, or what, is doing the excluding. For instance, Byrne (1999) takes issue with those sociologists (such as Bauman 1998) that see the new poor and unemployed as now completely irrelevant (as consumers or as producers) to the needs of post-Fordist societies. For Byrne, the socially excluded remain an essential reserve army of labour for such societies. This theoretical statement would seem to mesh with the empirical findings presented here. This approach understands social exclusion as a necessary and inevitable feature of late capitalist economies. Loïc Wacquant’s extended comparative discussion of the American Black ghetto and the impoverished French banlieues similarly stresses the connection between wider political and economic processes and the conditions of life in neighbourhoods of the socially excluded. He talks of a ‘deepening schism between rich and poor and between those stably employed in the core, skilled sectors of the economy and individuals trapped at the margins of an increasingly insecure, low-skill, service labour market, and the first among them the youths of neighbourhoods of relegation’ (2008: 25, our emphasis).

One advantage of (more developed) conceptualisations of ‘social exclusion’ over underclass theory is that the former calls for examination of the dynamic, over time processes that create exclusion (Hills 2002). As Littlewood and Herkommer put it (1999: 14) ‘exclusion is a process, where underclass is a more or less stable situation which results from the exclusionary process’. This view of process – of transition - has value at the individual, biographic level, highlighting ‘the experience of changing situations, of precarious conditions, of being periodically excluded and included…’ (ibid). We were unable to locate anything even approximating a ‘stable’ underclass, but this dynamic view of exclusion captures nicely the precariousness of economic life for our sample. It also points out the silliness of UK government policy attempts to respond to ‘youth exclusion’ by simply counting and dealing with that proportion of young people who are ‘not in education, employment or training’ at one moment in time. All our sample of 186 people had experience of being NEET. Perhaps only a quarter would have been at any given moment. The more important fact was that becoming NEET was a recurrent experience (despite repeated participation in EET) that signalled the lasting and collective economic marginality of the group.

This dynamic, processual view of social exclusion can be applied to collectivities and places as well as individuals. That all the individuals in our sample experienced the same economic fate (despite variability in other aspects of their lives and backgrounds, for example to do with patterns of offending, drug use, housing, parenthood and so on) demonstrates, firstly, the falsity of theories that rely on individual-level, deficit model explanations of exclusion and, secondly, the necessity of looking to the panorama of place, class and history in which these lives are lived.

Earlier we remarked upon the steep and speedy de-industrialisation of Teesside. Its industrialisation was the same. From a tiny, rural settlement in 1820, Middlesbrough became the fastest growing town in England during the 19th Century; born and bred as a thoroughly working-class, industrial town of iron, steel, heavy engineering and chemicals. Teesside was a place built for industry, the neighbourhoods we researched were constructed for industrial workers and their families and, until the latter third of the 20th Century, this was a place that ‘worked’ (Beynon et al. 1984). Returning to C.W. Mills, if we properly want to understand the ‘social exclusion’ of those we studied, and of their locales, we need situate qualitative description of the ‘personal troubles’ of individual biographies within the arena of ‘public issues’ of a changed social and economic structure.

Thus, our interviewees were born between the mid-70s and mid-80s, the period in which a quarter of all jobs – and a half of all manufacturing and construction jobs - were lost to the Teesside economy (MacDonald and Coffield 1991). The shocks and crises of global-local economic change scrapped culturally set ways of achieving secure, ‘respectable’ working-class adulthood. Contrary to underclass theory, working-class young adults here still possess conventional – even ‘hyper-conventional’ – attitudes to employment but have been dispossessed of opportunities to realise them in anything other than sub-standard, ‘poor work’. Casual work at ‘the turkey factory’ replaced skilled employment at ICI [7] . Understanding these historical processes of socio-economic change leads us to conclude that, in short hand, ‘the economically marginal’ is the best description of those to whom we talked and ‘economic marginalisation’ is the best explanation of their condition.

[1] This research is a collective effort: ‘we’ is preferred to ‘I’ in the writing of this paper. Co-researchers include Paul Mason, Jane Marsh, Donald Simpson, Les Johnston, Mark Simpson, Andrea Abbas, Mark Cieslik and Louise Ridley. Colin Webster and Tracy Shildrick contributed particularly to the theorisation and success of the research and continue to work with the author on these themes. I am indebted to them, to the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) and Joseph Rowntree Foundation (JRF) for their support and to all the participants in their study. All real names of informants and their immediate neighbourhoods have been changed.

[2] ‘Dole wallah’ is pejorative, colloquial term for someone deemed to prefer living on welfare to working for a living.

[3] A new Teesside study (Shildrick et al, 2009) will examine this question in respect of the labour market careers of a sample first interviewed as young adults but now reaching their thirties.

[4] Their grandfathers and sometimes fathers had previously worked in skilled, secure ‘upper’ working-class jobs.

[5] Levels of interest or engagement in formal politics were very low, although a handful of individuals were involved in grass-roots campaigns or organisations that aimed to improve local conditions.

[6] Not all ‘poor neighbourhoods’ or ‘socially excluded populations’ in the UK share these traits. Degrees of population stability and mono v. multiculturalism (in terms of social class as well as ethnicity) will affect the experience of social exclusion.

[7] ‘The turkey factory’ was a local poultry processing plant that emerged as the single largest employer, when all jobs ever taken had been counted, of our samples. ICI is a multinational chemical company which remains a presence on Teesside despite now being under foreign ownership and having shed thousands of jobs over recent decades.

References

Ball, S., Maguire, M. and Macrae, S. 2000: Choice, Pathways and Transitions Post-16: New Youth, New Economies in the Global City. London: Routledge/ Falmer.

Beynon, H., Hudson, R. and Sadler, D. 1994: A Place Called Teesside. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Brown, P. 1987: Schooling Ordinary Kids. London: Tavistock.

Byrne, D. 1999: Social Exclusion. Milton Keynes: Open University Press.

Cars, G., Madanipour, A. and Allen, J. 1998: Social Exclusion in European Cities, in: Madanipour, A., Cars, G. and J. Allen (eds.): Social Exclusion in European Cities. London: Jessica Kingsley, pp. 279-288.

Chamberlayne, P., Rustin, M. and Wengraf, T. (eds.) 2002: Biography and Social Exclusion in Europe. Bristol: Policy Press.

Coles, B. 1995: Youth and Social Policy. London: UCL Press.

DETR 2000: Index of Multiple Deprivation. London: Department of the Environment, Transport and the Regions.

Felstead, A. and Jewson, N. 1999: Flexible labour and non-standard employment, in: Felstead, A. and Jewson, N. (eds.): Global Trends in Flexible Labour. Basingstoke: Macmillan, pp. 1-20.

Fenton, S. and Dermott, E. 2006: Fragmented careers, in: Work, Employment and Society, 2, pp. 205-221.

Furlong, A. 1992: Growing Up in A Classless Society? Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Furlong, A. and Cartmel, F. 2004: Vulnerable Young Men in Fragile Labour Markets. York: Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

Furlong, A. and Cartmel, F. 2007: Young People and Social Change. Maidenhead: McGraw Hill.

Green, A. and Owen, D. 2006: The Geography of Poor Skills and Access to Work, York: Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

Hills, J. 2002: Does a focus on “social exclusion” change the policy response?, in: Hills, J., Le Grand, J. and Piachaud, D. (eds.): Understanding Social Exclusion. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Jeffs, T. and Smith, M. 1998: The problem of “youth” for youth work, in: Youth and Policy, 62, pp.45-66.

Johnston, L., MacDonald, R., Mason, P., Ridley, L. and Webster, C. 2000: Snakes & Ladders: Young People, Transitions & Social Exclusion. Bristol: Policy.

Kelvin, P. and Jarrett, J. 1985: Unemployment: Its Social Psychological Effects. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Littlewood, P. and Herkhommer, S. 1999: Identifying social exclusion, in: Littlewood, P. with Glorieux, I., Herkhommer, S. and Jonsson, I. (eds.): Social Exclusion in Europe. Aldershot: Ashgate.

MacDonald, R. 1997: Dangerous Youth and the Dangerous Class, in: MacDonald, R. (ed.): Youth, the ‘Underclass’ and Social Exclusion. London: Routledge.

MacDonald, R. 2009 (forthcoming): Precarious work: stepping stones or poverty traps?, in: Furlong, A. (ed.): The International Handbook of Youth and Young Adulthood. London: Routledge.

MacDonald, R. and Coffield, F. 1991: Risky Business? Youth and the Enterprise Culture. Lewes: Falmer Press.

MacDonald, R. and Marsh, J. 2001: Disconnected Youth?, in: Journal of Youth Studies, 4, pp. 373-391.

MacDonald, R. and Marsh, J. 2005: Disconnected Youth? Growing up in Britain’s Poor Neighbourhoods. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

MacDonald, R., Mason, P., Shildrick, T, Webster, C., Johnston, L. and Ridley, l. 2001: Snakes and Ladders: In Defence of Studies of Transition, in: Sociological Research Online, 4. Available under http://www.socresonline.org.uk/5/4/macdonald.html [20.12.2008]

McKnight, A. 2002: Low-paid Work: Drip-feeding the Poor, in: Hills, J., Le Grand, J., and Piachaud, D. (eds): Understanding Social Exclusion. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Merton, B. 1998: Finding the Missing. Leicester: Youth Work Press.

Mills, C. W. 1970: The Sociological Imagination. New York: Pelican.

Mizen, P. 2003: The Changing State of Youth. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

Murad, N. 2002: The shortest way out of work, in: Chamberlain, P., Rustin, M. and Wengraf, T. (eds.): Biography and Social Exclusion in Europe. Bristol: Policy Press.

Murray, C. 1990: The Emerging British Underclass. London: IEA.

Murray, C. 1994: Underclass: the Crisis Deepens. London: IEA.

O’ Donnell, K. and Sharpe, S. 2000: Uncertain Masculinities. London: Routledge.

Pohl, A., and Walther, A. 2007: Activating the disadvantaged, in: International Journal of Lifelong Education, 5, pp. 533-553.

Quintini, G., Martin, P. and Martin, S. 2007: The Changing Nature of the School to Work Transition Process in OECD Countries. Discussion paper 2582. Bonn: Institute for the Study of Labor.

Roberts, K. 1997: Is There a Youth Underclass? The Evidence from Youth Research, in: MacDonald, R. (ed.): Youth, the ‘Underclass’ and Social Exclusion. London: Routledge.

Roberts, K. 2001: Class in Modern Britain. London: Palgrave.

Shildrick, T., MacDonald, R. and Webster, C. 2009 (forthcoming): Two steps forward, two back? Understanding recurrent poverty. York: JRF.

Social Exclusion Unit 1998: Bringing Britain Together: A National Strategy for Neighbourhood Renewal. London: Social Exclusion Unit.

Toynbee, P. 2003: Hard work: life in low-pay Britain. London: Bloomsbury.

Wacquant, L. 2008: Urban Outcasts: A comparative sociology of advanced marginality. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Webster, C., Simpson, D., MacDonald, R., Abbas, A., Cieslik, M., Shildrick, T. and Simpson, M., 2004: Poor Transitions. Bristol: Policy Press/JRF.

Willis, P. 1977: Learning to Labour. London: Saxon House.

Wilson, W.J. 1996: When Work Disappears. New York: Knopf.

Author´s Address:

Prof Robert MacDonald

University of Teesside

School of Social Sciences and Law, Youth Research Group

UK - Middlesbrough, TS1 3BA

United Kingdom

Tel: ++44 1642

Email: R.MacDonald@tees.ac.uk

urn:nbn:de:0009-11-17005