Organisational Practice in the job centre – Variance or Homogeneity?

Navina Roman, Social Work and Organisation Studies, University of Hildesheim

1 Reforms and a New Organisation

The introduction of “modern labour market services” and associated efforts to implement new forms of employment intervention and placement have not only generated a demand for empirical research into the concrete practices (Kolbe and Reis 2005, 45), but also revealed a research desideratum relating to the job centre as organisation and to its organisational structures. Impact research (which is required by law) says nothing about actual interaction and communication processes in the job centres, nor about concrete organisational practices, because it generally focuses on events before or after the benefit application. Whatever happens in-between remains in a “black box”, “in the blind spot of unexplained variance” (Baethge-Kinsky et al. 2006, 2), which raises the question of how the employment service has constructed itself organisationally after the reforms. This gap is surprising, because significant elements of the Agenda 2010 reforms[1] – inspired by Anthony Giddens’s “third way” theory and reflexive modernity discourse and implemented by Chancellor Gerhard Schröder’s 1998–2005 coalition of Social Democrats and Greens – focussed precisely on processes of organisational change in the employment service.

Against this background of organisational change and the merging of different branches of unemployment assistance, the present contribution examines the emergence of a (new) organisation through social practice from an ethnographic perspective. Alongside unclarified power relations within the “new organisation”, it is also conceivable that the working attitudes and methods of local authority staff may have differed from those of the Federal Employment Agency on the grounds of their different prior experiences with different job-seeking clienteles. Additionally, given the lack of specific detail on organisation and processes included in the legislation, different models or even “internal sub-cultures” (Schottmayer 2003, 183) may continue to exist “under one roof”.

Does that degree of hybridity in the sense of different (organisational) cultures and historical residues in organisational processes lead to dynamic developments and differences in organisational practice?

In order to answer this question, I begin with the assertion that the new form of employment service has created an organisation that can be fully and adequately defined neither through the legislation nor through the management models of the constituent organisations. Instead, on the basis of structuration theory it should be regarded as an outcome of social practice. In that sense, within the bounds of their framework, the actors shape and modify their organisation as “lived practice”. As well as building directly on Giddens (1988, 1991, 1992) this understanding also draws on older work by Lipsky (1980), who argues that reforms have to be interpreted by the actors and translated into concrete action. That is the starting point for this contribution, which examines the way the employment service organisation is shaped as “lived” practice from the perspective of the actors (the staff) involved. Empirically, the research is based on a case study at one particular job centre using a quantitative staff survey and expert interviews with team leaders (see Roman 2014). The focus here is on the internal life of the job centre and its workforce by using parts of the quantitative staff survey.[2]

2 Background – Why a German job centre?

The German labour market and unemployment benefit system have witnessed a period of substantial change over the past fifteen years. While it is not so long since the rest of Europe regarded Germany as ossified, incapable of reform and failing the challenges of globalisation and structural transformation, the same country is today regarded as a European paragon. The German model stands out in EU-wide comparison in particular for simultaneous fundamental reforms in both the unemployment benefits system and the organisation of labour market services. No other country in the European Union has implemented such far-reaching changes in both spheres in such a short time (Knuth 2014, 9).

The central event in the history of the recent German reforms was Chancellor Gerhard Schröder’s appointment of the Hartz Commission, named after its chair Peter Hartz, with a remit to propose labour market reforms in the wake of a scandal involving falsification of statistics at the Federal Employment Agency in 2002 (for example Osiander and Steinke 2011, 7). Ever since, the new legislation has been widely known under the name “Hartz”. Although parliament sought to promote integrated case processing, especially by having benefits provided from a single agency in one building with a case manager retaining a complete overview of each case, the controversial “Hartz IV” measures have come in for great criticism. The enactment of the Social Code Book II (SGB II) on 1 January 2005 (the Hartz IV reforms) represented a radical shift in the organisation of the employment service by creating a new responsible body: the “consortium”. This is a dual structure composed of the Employment Agency (Bundesagentur für Arbeit) and the relevant local authority. The two bodies remain the separate employees of their respective staff. The legislation also allowed for further options, such as shared responsibility (under Article 6 of Social Code Book II) where the Employment Agency and the local authority each provided only those services for which they were ultimately responsible. There was also another (Article 6a of Social Code Book II) where the local authority took complete responsibility.[3]

One central objective of the labour market reforms was to avoid agency interfaces and unnecessary bureaucracy in employment promotion. As well as introducing new organisational responsibilities and business procedures, modifying benefits structures and implementing a new case management system largely based on agreed targets, important changes affecting daily work routines and client relationships were also made. Specifically, performance-based controlling is supposed to ensure that “customers” receive a professional service experience that “addresses their specific problems and leads to a resolution” (Bundesagentur für Arbeit 2012, 4).[4] Proactive “customer management” of “customer flow” seeks to give case managers more time for advising clients, by shifting certain administrative tasks to reception areas (Osiander and Steinke 2011, 7). In addition to these changes, the placement process itself was also restructured. To name just one example, after registering as unemployed “customers” are to identify their strengths and weaknesses. “Customer groups” and “integration agreements” are new instruments concluded between the benefits recipients and providers.

But the reforms left the agencies responsible for basic income support facing the challenge of putting the new arrangements into practice and in particular of making full use of the new possibilities. The consortiums, as completely new cooperative hybrid organisations, generated numerous problems and frictions. Ultimately the process also led to the Federal Constitutional Court ruling of 2007 that overturned the arrangements of Social Code Book II for setting up consortiums as incompatible with the right to local self-administration under Article 28 (2) of the German Basic Law, and to the ensuing reforms of 2010. The present contribution should be read against this background of difficulties and reorganisations, and the new form of employment service that has emerged across Germany under Article 44b of Social Code Book II should be understood as the emergence of a new organisation through social practice.

Even though some time has now passed since the original reforms were implemented, it must still be remembered that their introduction created great leeway for the establishment and organisational configuration of the job centres. Social Code Book II includes few concrete organisational stipulations and leaves many questions open, especially concerning the specifics of organisational structures and procedure. Job centres established under Social Code Book II have therefore developed diverse organisational models and a range of different systems for the client’s path from benefits application to placement in work. For various reasons many of the restrictions that applied to the old Employment Agencies no longer pertain to the consortiums, which as a new legal construct of equal partners enjoy broad options for local variations. To summarise, discussion of the reform of the base institution of German labour market policy through the adoption of Social Code Book II is in important respects still ongoing, at least as far as the organisation of the organisation is concerned.

3 The “Organisation of the Organisation” – A Research Gap

The desideratum of research on the “internal organisation of employment service” is broad and extends to the European sphere. Thus even expert concepts for the much-discussed question of case management in the areas covered by Social Code Book II relate only to certain aspects of case processing and remain trapped at an abstract level describing an ideal type that lacks theoretical grounding (Baethge-Kinsky et al. 2007; Deutscher Verein 2004; Göckler 2004, 2006).

In recent years, especially, the state itself has moved towards making its own provision of services the subject of scientific research. Accordingly there are already extensive published reports from the evaluation of the first three Hartz Acts (for example, Kaltenborn, Knerr and Schiwarov 2006). In relation to basic income support for job-seekers (Grundsicherung für Arbeitssuchende), Article 55 of Social Code Book II introduced through the “Fourth Law for Modern Services in the Labour Market” (Hartz IV) states that the impact of labour market integration interventions should be evaluated quickly and regularly. But statutory research commissioned to date has instead focussed largely on whether the consortiums or the permissible alternative of sole local authority responsibility represents the most effective structure for delivering the services in question. The third mode, in the form of separate processing of tasks by the two agencies (which was not originally intended by the legislation), long drew little interest, until the question was taken up by Kirsch et al. (2010, 17).

Specifically concerning the organisation of case processing in Social Code Book II, findings are available from large-scale quantitative surveys in particular: a descriptive analysis (under the “experimentation clause”, Article 6c of Social Code Book II) published by the Institut für Angewandte Wirtschaftsforschung (IAW) (2006a, 2006b), and an investigation commissioned by the German Association of Rural Districts and conducted by the Internationale Institut für Staats- und Europawissenschaften (ISE) (2006). A second field of research (also under Article 6c of Social Code Book II) addresses implementation and governance and evaluates the labour market success of the “local authority responsibility” and “consortium” models (BMAS 2008). There are also large-scale studies dedicated primarily to placement and advice practices, such as Böhringer et al. (2012), Hielscher and Ochs (2009), Schütz et al. (2011), as well as the slightly earlier work of Schütz and Mosley (2005).

But the most relevant studies for the present investigation are those that generate or at least build on empirical research into working processes and procedures. Starting points can be found in the work of Dunkel, Szymenderski and Voß (2004), who interviewed clients and staff, conducted participant observation and interviewed experts for their project on services as interaction.[5]

Going further back, one older study worth mentioning is Eberwein and Tholen’s investigation of job placement (1986), using empirical case studies and interviews with job-seekers, personnel managers and job advisors. In connection with the reform of social assistance and the merging of unemployment benefit for long-term unemployed (Arbeitslosenhilfe) and social assistance (Sozialhilfe) (Hess et al. 2004), the application of social work instruments and methods in labour market policy became the subject of theoretical and empirical work (for example Burghardt and Enggruber 2005). On that basis, there are studies that examine both the practice of social assistance and in some cases also the transition from social assistance to Social Code Book II (on this see also Baethge-Kinsky et al. 2006).

The conceptual study by Baethge-Kinsky and colleagues (2006, 2007) is especially valuable for the present investigation, as it asserts that the new benefits system for basic income support also represented the emergence of a new type of service, which the authors describe as “case processing”. Departing from the normative approach, the objective of their study was to clarify empirically how much advice, placement and case management “case processing” involves. In compiling a description of service processes “that cannot be acquired through either organisational analysis or quantitative statistical analysis” (Baethge-Kinsky et al. 2007, 6), the conceptual study can also be attributed a methodical as well as empirical interest. Another contribution is supplied by Ludwig-Mayerhofer et al. (2009), who link the macro-perspective of the organisational framework with its actual execution at the micro-level of concrete actual case processing. They used reconstructive/interpretative research methods to investigate the interactions arising during client appointments in the employment service.

Overall it must be noted that although there are a number of published studies dealing with the subject of the employment service, there is as yet little in the way of findings on the concrete organisational structures and procedures in the employment service. The literature on the identification of possible requirements for personnel and organisational development is even thinner. But studies such as the work of Niehaus and Schröer (2004) demonstrate an essential starting point for the present study, describing how the production of organisational realities, even in strongly regulated fields, depends on interactive construction performed by the actors.[6] This assumption, from a perspective of understanding organisations as social constructs and consequently ascribing a considerable role to the actors in shaping their own organisation, can be regarded as foundational for the present contribution.

4 Case Study – the Selected Organisation

No empirical analysis in the context of the organisation of services can be conducted without taking account of the organisational circumstances. Thus it must be noted that in the selected employment service a consortium had been established, which was responsible for the implementation of the new basic income support for job-seekers (Grundsicherung für Arbeitssuchende).[7] The components of this consortium were the local Employment Agency, representing the Federal Employment Agency, and the respective local authorities (Landkreise). The studied job centre employed team structures as the organisational framework for its work.[8] Ten regional teams were responsible for integration into the labour market, four of which were selected for the study.[9] Because of their composition and assignments, these employment service teams have to integrate and coordinate different perspectives and rationalities. The first step in the study was therefore to investigate the team structures and organisational circumstances by means of observation visits. Here the conceptual study by Baethge-Kinsky and colleagues (2006; 2007) was especially useful, because it supplies pointers for recording organisational conditions as “setting factors”. It was important not to neglect team composition and structure, as these could also play a major role in service management (Göckler 2006, 130).

A range of key data was gathered on the teams, of which only a fraction can be reported here (for more information, see Roman 2014). All teams followed the practice of assigning a case manager to each benefits applicant. Claims processing was conducted by middle-grade and senior benefit officers, while in many cases coordination and decision-making was conducted by a “tandem” of the responsible benefit officer and the case manager. Each team also included at least one senior benefit officer. All teams followed the practice of each case manager working closely together with no more than three benefit officers. In all teams more working hours were allocated to claims processing than to case management. It was conspicuous that teams differed in their handling of appointments and in their record-keeping. All the teams handled immediate offers (Sofortangebot) under Article 15a of Social Code Book II,[10] but differences in workflow organisation were identified in all stages. Thus one team had a dedicated case manager who dealt exclusively with such immediate offers. Only three of the four teams possessed a client management system, which represents the first point of contact for clients, and its organisation varied between teams. The leadership of the teams also differed by origin: teams B and D were under local authority leadership, teams A and C led by managers answerable to the Employment Agency.

Overall a degree of heterogeneity can certainly be identified in both team structure and workflow organisation, suggesting that this could also be reflected in the survey responses.

5 Sample and Survey

The data on which the following analyses are based was gathered through a quantitative questionnaire survey conducted in the selected job centre. The survey instrument developed specially for this purpose examined the three dimensions of “experience of daily work and working situation”, “elements of the management system” and “teamwork and communication”, as well as socio-demographic data. The data collection phase was conducted in summer 2008, in consultation with the project steering committee and the leaders of the teams. In order to the ethnographic perspective and to preserve the anonymity of what was an extremely small sample for a quantitative survey (82 questionnaires distributed), the questionnaires were returned in two parts in two different envelopes: one for the socio-demographic data, another for the items (parts II–VII). While this procedure was necessary to avoid the risk of identification of individuals, its price was the loss of any possibility of analysis directly integrating the personal data. Fifty-three completed Part I questionnaires (socio-demographic data) were returned, representing a response rate of 65 percent, and analysed separately. A slightly higher response rate was achieved for the completed Part II questionnaires, of which fifty-five (67 percent) were returned:

|

|

Team A |

Team B |

Team C |

Team D |

|

Reception and team support |

0% |

9% |

4.8% |

6.7% |

|

Case managers |

37.5 % |

45.5% |

38.1% |

20.0% |

|

Benefit officers |

62.5 % |

45.5% |

42.8% |

60% |

|

not specified |

0% |

0% |

14.3% |

13.3% |

Figure 1: Distribution of functions

in sample (N = 55)

Benefit officers represent the largest proportion in all teams and are particularly well-represented in the overall sample, with 51 percent (see Figure 1). The market and integration division, to which the case managers belong, was rather less strongly represented, with 34.5 percent, while weakest representation was found for team support and reception division with just 5.5 percent.

Referring to Part I and in terms of employer, 69.6 percent of the respondents reported belonging to the local authority, 30.4 percent to the Employment Agency. This higher proportion of local authority staff was found across all teams and functional divisions. Two-thirds of respondents were employed on a permanent basis (66.3 percent). No significant differences were found to suggest that the staff of any particular employment agency were more likely to be employed on a temporary basis.

In terms of age structure, the selected employment service transpired to have a particularly young workforce. Thus 50.9 percent of respondents indicated that they were aged 30 years or younger, followed by the 31–40-year-olds (28.3 percent). Only 11.3 percent were 41–50 years old and just 9.4 percent reported being older than 50. The mean age of the oldest team, Team B, was a decade higher than that of the youngest, Team A.

6 Variance – or “Lived” Unity?

As already mentioned in the introduction, this contribution set out to consider the question of whether different experiences of everyday organisational practice exist “under a single roof” at the employment service. The following extract refers to two of the three dimensions of “experience of daily work and working situation” and “elements of the management system”.

However, the findings of the survey, based on fifty-five returned questionnaires, reveal only weak variance between team types, few agency-specific differences and even fewer function-specific differences. Instead, in this respect, the data largely reflects a situation of homogeneity.

6.1 Experience and Assessment of the Daily Working Situation

The subjective assessments of all respondents concerning their own working situation were recorded using a set of questions based on a unipolar 4-stage Likert scale, where 1 represented approval or a positive attitude, 4 disagreement or negative.

The results provide a comprehensive picture of working life and experiences in the selected employment service organisation. To assess the central hypothesis that there will be differences associated with belonging to different team, agency or function, priority is given in the following to findings that reveal the relationships between particular items and those categories. On the basis of the central assumption that different and team-specific procedures will result in different experiences of the employment service organisation, it may also be conjectured that the merging of the two organisations – local authority and Federal Employment Agency – will strongly affect staff, in particular in the form of particular working procedures and processes, organisational loyalties, and team structures and constellations.

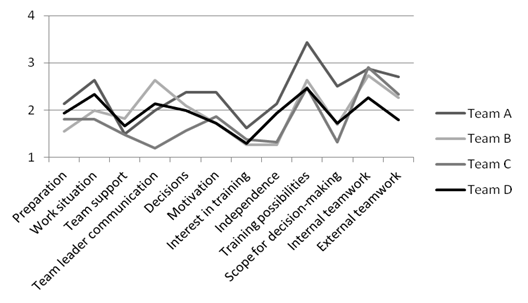

Figure 2: Team-specific means for daily working situation items

Figure 2 illustrates the means of the individual variables of the “experience of daily work and working situation” dimension on the basis of team membership. It is immediately apparent that team membership is associated with specific differences in relation to the experience of daily work and working situation. Note that aspects relating to mutual support within the team was experienced as positive in all cases, with values from M = 1.48 to M = 1.82 (N = 55). Interest in training was also strong in all teams (Values range from M = 1.27 to M = 1.63; N = 55). On the other hand, satisfaction with offered training possibilities in particular, with values between M = 2.47 and M = 3.43, was rather negative in all the four teams (N = 54).

Team-specific differences in the assessment of aspects of the daily working situation were found, for example, in particular in “preparation for routine tasks” (preparation) (N = 54) where there was a spread of values ranging from very positive in Team B (M = 1.55) to less positive in Team A (M = 2.13).[11] Obvious differences were also found in satisfaction with the possibilities for “independent execution of routine tasks” (independence) (N = 55), where the recorded values ranged from M = 1.27 in Team B to M = 2.13 in Team A. Whereas satisfaction with participation in decision-making (decisions) was especially high in Team C, with M = 1.57, the results for this item in the other teams trended more negative (N = 54).

An analysis of variance was conducted to ascertain whether the few and small differences ascertained in this dimension are confirmed in the statistical population. In this confirmatory analysis involving the ANOVA method and extrapolation to the statistical population, the variance was further reduced. The subsequent Levene’s test revealed significance at a level suggesting small differences in experience within the statistical population in relation to only four points: “communication between team and leaders” (.000*), “participation in decision-making” (.028*), “independent execution of tasks” (.001*) and “scope for decision-making” (.001*).[12]

Figure 3: Function-specific means for daily working situation items

If we now compare the means for benefit officers and case managers, we find a pattern that at least at first glance appears to show extensive conformity of responses.[13] As Figure 3 shows, there is obvious broad agreement among the claims-processing benefit officers and the case managers in their assessments of the aspects of experience under investigation here. Slight differences can, however, be identified in specific variables. While the case managers were very satisfied with the way their colleagues supported one another (M = 1.21; N = 55), the value for benefit officers – while also within the positive range – was noticeably less so (M = 1.84). A strong interest in acquiring additional qualifications was identified among the former (M = 1.11), while the value for the latter was lower (although still relatively high) (M = 1.58; N = 54).

An analysis of variance and subsequent post-hoc testing (Levene’s test or Tamhane’s T2), however, revealed that after extrapolation to the statistical population only two variables demonstrated significant differences between benefit officers and case managers (“Team support” p =.040* and “Interest in training” p = .002*). Overall, extrapolated to the statistical population, the benefit officers were less positive about the way their colleagues support one another (M = 1.84; SD = .800) than the case managers (M = 1,21; SD =.700). On the other hand, the case managers reported even stronger interest in job-related training (M = 1.11; SD = .301) than the already high mean for the benefit officers (M = 1.58; SD = .584).

6.2 Experience and Assessment of the Management System and Processes

In this dimension, too, differences associated with team, agency or function was expected. The set of items used here related to assessments of particular aspects of the management system and routine processes. In order to discover whether the expectation is correct, the data was analysed to reveal possible associations between particular items and team membership or functional division.

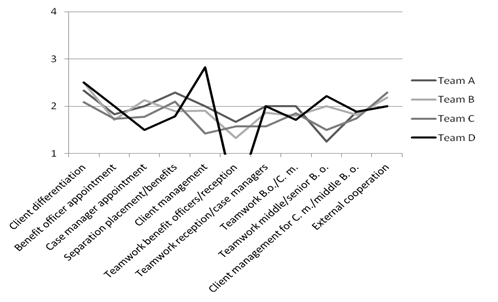

Figure 4: Team-specific means for management system and processes items

As can be seen in Figure 4, most of the investigated items produced only small differences between the teams. The very conspicuous value of M = 0 for “teamwork benefit officers/reception” for Team D is simply a function of that team having no reception at the time of the survey, and there accordingly being no data for that category (N = 27).

The data on aspects of “lived practice” examined here reveal extensive overall homogeneity. However, client differentiation was viewed particularly critically, with a mean above M = 2.0 in all the teams, as was cooperation with external agencies. On the other hand, the interface between client management and case managers and middle-grade benefit officers were viewed especially positively across all the teams, with means between M = 1.75 and M = 1.88 (N = 52). Further team-specific differences were identified in relation to the variable “teamwork middle/senior benefit officers” (range from M = 1.25 in Team A to M = 2.22 in Team D; N = 34).

In order to test whether the (small) team-specific differences found in the survey data also applied to the statistical population, an ANOVA was again conducted. The results of the subsequent post-hoc testing (Levene’s test and Tamhane’s T2) showed that only for the variable “client management system” was there a significant difference (p = .001*; SD = 0.33; mean difference = 1.41; N = 46) (also in the statistical population) between Team C and Team D:[14] the assessment of client management in Team C (M = 1.43; SD = .676) was significantly more positive than in Team D (M = 2.83; SD = .983). Here it should be noted that these two teams differed in many other respects, too. In fact they can be characterised as especially different. Unlike Team C, Team D was an urban located team under local authority leadership and possessed no permanent client management system. For this reason many respondents in Team D chose the response category “not relevant to me”.

To summarise the results thus far, little in the way of team- or agency-specific differences were identified in relation to assessments of particular elements of the management system or of specific processes. Next the data was analysed to discover whether function might be associated with possible differences.

The data for management system and processes was analysed to test whether there were significant differences between response means associated with the functions of the respondents. The earlier results for daily working situation (section 6.1) identified few and small differences between the benefit officers and the case managers.

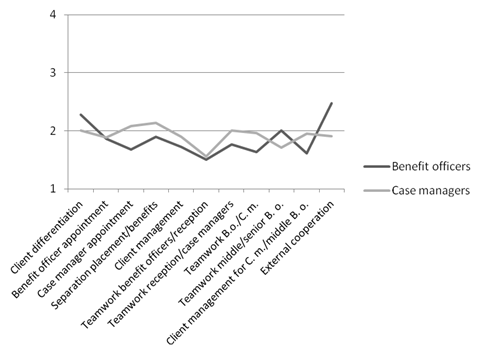

Figure 5: Function-specific means for management system and processes items

Figure 5 shows very clearly that there are only small differences between the benefit officers and case managers with respect to their assessments of the functionality of the management system and particular processes. The values extend between M = 1.50 (teamwork benefit officers/reception; N = 27) and M = 2.47 (external cooperation; N = 48). On closer examination, it was found that benefit officers assessed the functionality of their cooperation with external agencies (M = 2.47; SD = 0.72) noticeably more negatively than the case managers (M = 1.91; SD = 0.42). The post-ANOVA Levene’s test (p < .05) produced the conditions required for Tamhane’s T2. This in turn confirmed (p = .025*) that the significant difference between the case managers and the benefit officers described above extrapolates to the statistical population.

To summarise, significant differences were found between the assessments of specific elements of the job centre and of the functioning of concrete working processes in the “lived” working routine associated with particular sub-groups, but only concerning a handful of points.

7 Thinking Ahead – “Learned” Homogeneity?

The idea that the new form of employment service has given rise to a (new) organisation that cannot be adequately defined through either legislation or management models, but can be understood on the basis of structuration theory as an outcome of social practice, is central to this contribution. The explorative recording of “setting factors”, in the sense of the circumstances of the individual teams, produced indications of team-specific organisational and activity structures. These setting factors confirmed the assumption stated at the outset, that there are differences between teams and management models. If the “lived job centre” is understood as the outcome of social practice, different ways of organising the daily work will be lived “under one roof” and may also surface as organisational culture(s).

It is certainly conceivable that even if the different team models were regarded as the basis, several organisational cultures could exist in parallel in one building, in the sense of subcultures. The idea that there could be a close connection between the emergence of an underlying consensus within a culture and shared interpretations and actions by the members of that culture expands the concept and makes the emergence of a homogenous culture encompassing an entire organisation rather unlikely. Thus, in particular with respect to the organisational changes and the merging of different branches of the unemployment system, in terms of labour-market-linked social services and the everyday work of the job centres, the expected outcome would be hybridity characterised by different cultures and historical residues in the organisational processes.[15]

The survey demonstrates that despite the different procedural models there were only small differences in the “lived employment service organisation”. These were found – where they existed at all – more on the basis of team membership than of function. This result could in itself suggest a strong routine and/or comparability of working procedures at the level of different functions. However the small magnitude of detected differences on the basis of team membership also suggests a certain equalisation of lived and experienced practice within the selected employment service.

But what could be the meaning of the relative homogeneity by team and it’s function “under one roof” revealed by the data?

As already described, the staff of the job centre must integrate and coordinate different perspectives and rationalities. But the quantitative results show that while evidence of differences in the “lived” routines of the employment service organisation may be manifested “under one roof”, they are extremely small in relation to the statistical population. Consequently, the essence of the quantitative material is that the central hypothesis – that team-specific differences will result in different and in particular team- and/or function-specific experiences within the employment service organisation – must be largely rejected. Despite small but statistically significant variance in relation to individual items, an obvious tendency towards homogeneity cannot be denied. To put it in black and white: Even if it is not obvious at first glance in relation to the team-specific procedural models, in relation to the concept of organisational culture there is certainly a tendency towards homogenisation.

If we now bring in the structuration paradigm, this homogeneity of the actors of the “lived organisation” is both constructed and presupposed. In broad terms it speaks less for differentiated organisational (sub)cultures, but bluntly a “lived organisational culture of standardisation”. The procedures of the teams in the selected employment service are subject to a process of homogenisation, producing uniformity across teams even in the framework of experiences within the organisation.

It must be noted that organisational culture(s) are understood in this contribution not as management concepts but as “lived” practice. To quote Schein, the processual, vital and developmental aspects of cultures represent a “dynamic phenomenon” (Schein 2004, 1). An organisational culture is “a pattern of shared assumptions that the group has learned in the course of dealing with problems of external adaptation and internal integration, and which having stood the test of time is regarded as binding” (Schein 1995, 25). The integrating force in this approach is the “shared assumptions” in the sense of deeply rooted certainties of which the actors themselves are unaware. Applied to the present study, a collective standardisation is constructed, “lived” and “experienced” through daily social practice in the employment service. Guided by the narrowly economic criteria of rationality and efficiency, the actors of the employment service “learn” to standardise their working procedures. As a result the employment service organisation is a culture of standardisation expressed in processes of interpretation and action and representing the thoughts, feelings and actions of its members. Intensifying and increasingly standardised interaction routines reveal an organisation that was formerly consciously orientated on heterogeneity in its procedures and its agency structure to in fact possess an increasingly standardised organisational culture expressed in homogenising social practice. But this orientation enables neither a real “living” of hybridity nor recognition of the certainly highly organisation-specific self-perceptions of the actors.

Finally, it must be remembered that hybrid administration also created problems of its own. Thus two organisations with different “production logics” were brought together and with unclear lines of responsibility on both sides. Even before the reforms, it must be noted, a massive focus on uniformity, targets and particular rules was already practised throughout large parts of the organisation: Unlike the local authorities, the Federal Employment Agency was a strongly top-down, hierarchically-structured organisation. What is striking is that that orientation also appears in this “new” phenomenon of the job centre with its dual structures. Standardisation is also promoted by the introduction of system management in itself, for promoting a structure designed for uniformity may enhance efficiency and control of those teams, as well as transparency. Moreover, especially in administration, an organisational culture implies an external orientation on customers and policy-makers towards whom there are legitimate grounds to make actions dependable and transparent (Faust 2003, 96).

But it is also conceivable that the leeway to develop team-specific procedures granted at the beginning of the restructuring is also expressed in a wish for standardised working processes and procedures. The creation of the new institution of the job centre and the resulting uncertainties may have fostered a desire for technocratic rationality and standardisation of organisational practice. Thus the chances for staff to actually “live” the differences, which (re)appeared with the introduction of the job centres, are small. The process of learned (self-) standardisation (which in micro-political terms could even be defined as a kind of (self-) disempowerment) can certainly be understood as a more or less intentional consequence of structuration. The hybridity of the “employment service organisation” and its differentiated team structures and procedures cannot, strictly speaking, find recognition. Will the new organisation gradually leave behind differences and historic residues?

Although standardisation is “lived” and to an extent also driven by the actors, it is revealed at the same time to represent containment. Organisational learning processes that extend beyond a pure standardisation of procedures operate within narrowly defined bounds, leading actors to retreat into the routines of the own sphere of responsibility and competence. This can hinder organisational learning (apart from standardisation) and possibly also the transfer of individual and organisational knowledge. The result is that the employment service is lived as a form of bureaucracy in the Weberian tradition, even though it is supposed to be a child of the third way of reflexive modernity as propagated by Anthony Giddens in the 1990s (Giddens 1991, 1992).

References

Baethge-Kinsky, V., Bartelheimer, P., Henke, J., Land, R., Willisch A., & Wolf, A. (2006). Neue soziale Dienstleistungen nach SGB II (Konzeptstudie): Forschungsbericht. Göttingen.

Baethge-Kinsky, V., Bartelheimer, P., & Wagner, A. (2007). Zukunft der JobCenter – Zur Lage der Grundsicherung nach dem Verfassungsgerichtsurteil vom 20.12.2007. online: http://www.monapoli.de/Zukunft_der_JobCenter.pdf

Böhringer, D., Karl, U., Müller, H., Schöer, W., & Wolff, S. (2012). Den Fall bearbeitbar halten: Gespräche in Jobcentern mit jungen Menschen. Opladen, Berlin, Toronto

Bundesagentur für Arbeit (2012). Das arbeitnehmerorientierte Integrationskonzept der Bundesagentur für Arbeit (SGB II und SGB III). Nuremberg.

Bundesministerium für Arbeit und Soziales (Ed). Evaluation der Experimentierklausel nach § 6c SGB II –Untersuchungsfeld 2: Implementations- und Governanceanalyse, Abschlussbericht Mai 2008. online: http://www.bmas.de/DE/Service/Publikationen/Forschungsberichte/Forschungsbericht-Evaluation-Experimentierklausel-SGBII/forschungsbericht-f386.html

Burghart, H., & Enggruber, R. (Eds.) (2005). Soziale Dienstleistungen am Arbeitsmarkt: Soziale Arbeit zwischen Arbeitsmarkt- und Sozialpolitik. Weinheim and Munich.

Deutscher Verein für öffentliche und private Fürsorge (2004). Empfehlungen des Deutschen Vereins zu Qualitätsstandards für das Fallmanagement. In Nachrichtendienst des Deutschen Vereins für öffentliche und private Fürsorge 84 (5): 149–153)

Dunkel, W., Szymenderski, P., & Voß, G. G. (2004). Dienstleistung als Interaktion: Ein Forschungsprojekt. In Dienstleistung als Interaktion, Beiträge aus einem Forschungsprojekt Altenpflege – Deutsche Bahn – Call Center, ed. Wolfgang Dunkel and G. Günter Voß, 11–27. Munich.

Eberwein, W., & Tholen, J. (1986). Öffentliche Arbeitsvermittlung als politisch-sozialer Prozess: Über die Möglichkeiten und Grenzen staatlicher Arbeitsmarktpolitik am Beispiel der Region Bremen. Bremen.

Faust, T. (2003). Organisationskultur und Ethik: Perspektiven für öffentliche Verwaltungen. Berlin.

Giddens, A. (1991). Structuration theory: Past, present and future. In Giddens’ theory of structuration. A critical appreciation, ed Christopher G. A. Bryant and David Jary, 201–221. London and New York.

Giddens, A. (1992). Die Konstitution der Gesellschaft: Grundzüge einer Theorie der Strukturierung. Frankfurt am Main.

Göckler, R. (2004). Argumente für ein beschäftigungsorientiertes Fallmanagement in den Arbeitsgemeinschaften. Nuremberg.

Göckler, R. (2006). Beschäftigungsorientiertes Fallmanagement: Praxisorientierte Betreuung und Vermittlung in der Grundsicherung für Arbeitssuchende (SGB II): Eine Einführung. 2nd exp. ed. Regensburg and Berlin.

Hess, D., Schröder, H., Smid, M., & Reis, C. (2004). MoZArT – neue Strukturen für Jobs: Abschlussbericht der wissenschaftlichen Begleitforschung. Bundesministerium für Wirtschaft und Arbeit.

Hielscher, V., & Ochs, P. (2009). Arbeitslose als Kunden? Beratungsgespräche in der Arbeitsvermittlung zwischen Druck und Dialog. Berlin.

Institut für Angewandte Wirtschaftsforschung (IAW) (2006a). Auftaktworkshop zur Evaluation der Experimentierklausel nach § 6c SGB II – Untersuchungsfeld 1: Deskriptive Analyse und Matching: Vortrag von Dr. Harald Strotmann. Berlin.

Institut für Angewandte Wirtschaftsforschung (IAW) (2006b). Evaluation der Experimentierklausel nach § 6c SGB II – Vergleichende Evaluation des arbeitsmarktpolitischen Erfolgs der Modelle Aufgabenwahrnehmung „zugelassene kommunale Träger“ und „Arbeitsgemeinschaft“ – Untersuchungsfeld I: „Deskriptive Analyse und Matching“ Jahresbericht. Tübingen.

Internationales Institut für Staats- und Europawissenschaften (ISE) (2006). Evaluation der Aufgabenträgerschaft nach dem SGB II: Ergebnisse der zweiten Feldphase und der ersten flächendeckenden Erhebung: Vortrag von Professor Dr. Joachim Hesse. n. p.

Kaltenborn, B., Knerr, P., & Schiwarow, J. (2006). Hartz: Bilanz der Arbeitsmarkt- und Beschäftigungspolitik. Berlin.

Kirsch, J., Knuth, M., Mühge, G., & Schweer, O. (2010). Der Abschied von der Dienstleistung aus einer Hand: Die getrennte Wahrnehmung der Aufgaben nach dem Sozialgesetzbuch II. Berlin: Hans-Böckler-Stiftung.

Knuth, M. (2014). Rosige Zeiten am Arbeitsmarkt? Strukturreformen und „Beschäftigungswunder“: Expertise im Auftrag der Abteilung Wirtschafts- und Sozialpolitik der Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, WISO Diskurs, July. Bonn: FES.

Kolbe, C., & Reis, C. (2005). Zur Praxis des Case Management in der Sozialhilfe und der kommunalen Beschäftigungsförderung: Ein Probelauf für das Fallmanagement? ARCHIV für Wissenschaft und Praxis der sozialen Arbeit 36 (1): 62–75.

Lipsky, M. (1980). Street-level bureaucracy: Dilemmas of the individual in public services. New York.

Ludwig-Mayerhofer, W., Behrend, O., & Sondermann, A. (2009). Auf der Suche nach der verlorenen Arbeit: Arbeitslose und Arbeitsvermittler im neuen Arbeitsmarktregime. Konstanz.

Ludwig-Mayerhofer, W., Sondermann, A., & Behrend, O. (2007). Jedes starre Konzept ist schlecht und passt net' in diese Welt. Nutzen und Nachteil der Standardisierung der Beratungs- und Vermittlungstätigkeit in der Arbeitsvermittlung. Special edition of Prokla: Zeitschrift für kritische Sozialwissenschaft 37 (148): 369–81

Niehaus, M., & Schröer, N. (2004). Geständnismotivierung in Beschuldigtenvernehmungen: Zur hermeneutischen und diskursanalytischen Rekonstruktion von Wissen. Sozialer Sinn: Zeitschrift für hermeneutische Sozialforschung 5 (1): 71–93.

Osiander, C., & Steinke, J. (2011). Street level bureaucrats in der Arbeitsverwaltung. Dienstleistungsprozesse und reformierte Arbeitsvermittlung aus Sicht der Vermittler. IAB Discussion Paper 15. Nuremberg.

Roman, N. (2014). Die eindimensionale Organisation: Gelebte Praxis in der Arbeitsverwaltung als Perspektive der Personalentwicklung. Wiesbaden.

Schein, E. H. (1995). Unternehmenskultur: Ein Handbuch für Führungskräfte. Frankfurt am Main 1995.

Schein, E. H. (2004) [1985]. Organizational culture and leadership, 3rd ed. San Francisco.

Schottmayer, M. (2003). Subkulturen im Betrieb. Münster.

Schütz, H., & Mosley, H. (Eds.) (2005). Arbeitsagenturen auf dem Prüfstand: Leistungsvergleich und Reformpraxis der Arbeitsvermittlung. Special edition of Modernisierung des öffentlichen Sektors 24.

Schütz, H., Stemwede, J., Schröder, H., Kaltenborn, B., Wielage, N., Christ, G., & Kupka, P. (2011). Vermittlung und Beratung in der Praxis: Eine Analyse von Dienstleistungsprozessen am Arbeitsmarkt, IAB-Bibliothek 330. Bielefeld.

Author´s

Address:

Navina Roman

Social Work and Organisation Studies

University of Hildesheim

Email: romann@uni-hildesheim.de