Junctions, Pathways and Turning Points in Biographical Genesis of Right-Wing Extremism

Thomas Gabriel & Samuel Keller, Zurich University of Applied Sciences, School of Social Work

This article adopts the hypothesis that the primary organizational structures of the family and immediate social environment play a decisive role in explaining the genesis of racist attitudes and behavioral disposition. Processes of upbringing and socialization are always to be understood as products of active subjective interaction and thus to be reconstructed as such within the framework of social work research. In the context of the research this article is based on, it was of special interest to scrutinize the biographies of young people by analyzing junctions and relevant turning points on their pathways to right-wing extremism. This biographical junctions and turning points are seen as timeframes where agency and biographical meaning gets evident and can be re-constructed. This method is supported by more recent findings which unanimously warn against relying on the results of socialization while neglecting that the acquisition of social disposition is a process which is highly individual in characteristic. To make the model of junctions and turning points understandable, the second half of this article discusses a generic case of a young man and his subjectively relevant meanings of becoming and being right-wing extremist.

1 Evidence of junctions and turning points to understand genesis of right-wing extremism

Although there is almost unanimous agreement in scientific circles that in Western European democracies rightwing-extremism and xenophobia are not primarily youth-related phenomena this is how the problem is perceived by the majority of the public, as well as in some professional discourses. In making the phenomenology of adolescent criminal activity the central issue, one neglects to consider that on the level of racist patterns of interpretation, comparable attitudes can be found among both adolescents and adults. Findings of the European Monitoring Centre on Racism and Xenophobia point out that 33% of the interviewed persons defined themselves as “quite racist” or “very racist” in all 15 member states of the EC (see Westin 2003). Generally a multitude of studies indicate the social normality of nationalistic attitudes in western democracies (see Edinger & Hallermann 2009; Braunthal 2009; Stock, Tausch & Vor 2008). Thus such attitudes and opinions can be found in much broader parts of society and not only at the edge (“extreme”) or in the form of juvenile delinquency.

Despite ongoing debates on how to define right-wing-extremism, there is wide academic consensus that rightwing-extremism stands contrary to the tradition of human rights and democratic constitutions (see Mammone, Godin & Jenkins 2013). That is why it is to be defined as essentially anti-democratic. Right-wing extremism is directed against parliamentary and pluralistic democratic political values and systems. Forms of ethnocentricity such as overt racism or nationalism are the core of an ideology that claims superiority to all other values. These extremists principally advocate inequality and an aggressive nationalism that breeds resentment against ethnically foreign groups. Nevertheless it has to be kept in mind that even if they match the definition of right-wing extremism on an individual level not all attributes have to contradict democratic political values (see Altermatt & Kriesi 1995, 18). From these terminological difficulties one basic difficulty arises: Behaviour or actions need not necessarily be immediately attributable to attitudes, orientations and values; just as they may be insufficient as explanations for actual behaviour. On these grounds it is evident that one cannot explain extremist behaviour of juveniles ‘only’ as politically motivated or as a possible expression of adolescence, but that one should try, instead, to understand what it stands for in their biographies and current living situation.

Depending on his or her family background, peers and social environment, the strength of an adolescent's ego can vary significantly, i.e. the ability to balance social demands and individual needs (see Becker 2008; Siedler 2006). In a continuum, the attitudes would range from an individual's ability to resist racist assault up to his or her capability to commit racist acts of violence. In extreme cases adolescents may see themselves as the “executive body” of their parents, their neighbourhood or their country. Thus, one of the questions to be asked is why some young people are susceptible to right-wing extremist ideologies or participate in violent acts of aggression while others, living in similar economic and social conditions, do not have this tendency. This question, which calls the logic of subsumption ex post facto into question, is where methodological concepts of “turning points” and “pathways” emerge (see Gilligan 2009): which crucial turning point can be found in the genesis of right-wing extremism, how can it be defined, analysed and biographically understood? And to distinguish the concept of turning points: which junctions and pathways lead to this relevant turning point?

2 Research project: goals, hypothesis and the epistemological role of turning points

In a Swiss national research project on causes of and countermeasures against right-wing extremism, we focused on those junctions and re-constructed turning points to understand individual logics of juvenile right-wing-actions. Insights, examples and the methodological discussion below are based on this project, which was part of the National Research Program 40+ “Right-Wing Extremism – Causes and Countermeasures” (1 April 2004 to 31 March 2007). Our project was carried out at the University of Zurich and called “Parenting and Right-Wing Extremism: Analysis of the Biographical Genesis of Racism among Young People” (see Gabriel 2009). A main goal of the project was to find differentiated answers to questions concerning the genesis of right-wing extremism among adolescents in Switzerland.

The concern mentioned above was integrated in the research project because it deals with juvenile actors in the area of right-wing extremism. By the selection of the research sample of young right-wing extremists – followed by a highly sensitive access to the field – the connection between prejudice and discrimination on the level of action was made. Hereby it was possible to draw conclusions about the “conditioning moments” in a social context and inside the family (see Möller & Schuhmacher 2007). This seems important as stereotypes, prejudices and factual discrimination in a social context constitute the interactive dimensions of ethnical marginalisation; they are connected more or less closely among themselves and can differ in terms of how ethnocentristic or racist they are in nature.

Our research project focused on the reconstruction of parenting and socialisation processes. This allowed us to identify the central factors which contribute to the genesis of racist and xenophobic interpretation patterns and their meaning for the interviewed juveniles. In its attempt to reach this goal, the study examines the complexity of intra-familial factors, such as the emotional-affective climate, parenting styles, conflict culture and quality of relationships in relation to the socio-structural environmental influences affecting these young people. From a pedagogical point of view, the realisation of racist behaviour and interpretation patterns is to be seen as highly individual and should not be judged as positive or negative on the level of the individual cases. The few existing studies on the subject of xenophobia and racism only examined the quality of relationship between parents and children from the subjective view of the juveniles. This could be one reason for individual contradictions since the subjective “truth” about the relationship to one’s parents is always also a product of one’s successful integration (see Gabriel 2001, 91). Multi-generational analyses and an analysis of biographical turning points have so far been neglected by the researchers of xenophobic violent behaviour in adolescents. But they might be able to pinpoint the quality of interpersonal familial relationships and its relevance for pathways leading to right-wing extremism on an inter-subjective level.

In consideration of this short theoretical and empirical localisation, three hypotheses emerge in which the different meaning of junctions and turning points in familial contexts becomes apparent:

· The biographies of the young people contain development paths and junctions that lead to the genesis or intensification and reinforcement of racist interpretation and behaviour patterns. Narrative biographical data are necessary to identify them (see Rosenthal 1993).

· Family culture and social environment in the (‘interpendent’) context of crucial junctions and pathways leading to a relevant turning point are key influences on the individual genesis of racist attitudes and violent right-wing extremism among adolescents.

· Parenting styles, inter-generative patterns and relationships contribute to the development of racist and right-wing attitudes.

3 Methodological thoughts and consequences for research design

This study adopted the hypothesis that it is necessary to understand primary organisational structures of the family and immediate social environment when seeking to explain the genesis of racist attitudes and behavioural disposition. Yet, the processes of parenting and socialisation are always to be understood as products of active subjective interaction. Thus they should be reconstructed as such within the framework of this research project. The aim was to determine the influencing factors leading to the development of racist attitudes and behavioural disposition in juveniles in an interactive dimension. These dynamic influences can reinforce, relativise or neutralize each other. Thus a highly intensive and detailed analysis of selective biographical pathways and their turning points (see Gilligan 2009) is a promising way to handle these issues methodologically. In this context, it was of special interest to scrutinise the biographies, which would then make it possible to hermeneutically reconstruct (see Schütze 2004; Rosenthal 1993), understand and analyse the genesis and intensification of racist interpretation and behaviour patterns (see Köttig 2004). This method is supported by more recent findings which unanimously warn of relying on the results of socialization while neglecting that the acquisition of social disposition is a highly individual process.

This article will concentrate on one possible concept to reconstruct young people’s biographies containing right-wing extremist action by following one specific generic case. In these biographies, pathways and junctions as well as turning points in the genesis of right-wing extremism firstly have a subjective logic – no matter how societies and researchers judge the political point of view. Following these epistemological interests, it is not possible to describe their turning points retrospectively as positive or negative in a normative way. That is also why, for now, we prefer to focus on the terms “junction” and “pathways” to describe small passages or situations in biographies where narration reveals relevant issues and influences on disposition and/or action. The results of existing macro-sociological studies must not at all be related to the actual processes of attitude which appear in the biographies. This is due to the gaps existing between values that are expressed, the underlying patterns of mentality, and feelings of resentment, actual motives and behaviour. From this it follows that their genesis can be explained on comparatively highly aggregate data levels. However, such behavioural patterns seem to be actualised on an extremely small scale, i.e. not on a macro-level but, at most, on the level of figurations between social macro and micro levels (see Elias 2000). All findings show that the primary organisations, i.e. the adolescent’s family and the immediate social groups, appear to be particularly relevant for explaining the genesis of rightwing radical motives and actions (see Rieker 2002).

The aim of this chosen methodological way was to work out thematic aspects concerning the biography of the young individuals in connection with characteristics of their families/culture of growing up such as the following ones:

· genesis of racism, pathways and junctions in the juveniles’ biographies;

· communication and conflict cultures within the family;

· parenting styles and patterns;

· quality of attachment between the generations (bonding experiences, moral heteronomy, maternal affection, authoritarian dispositions, etc.);

· central topics of oral history passed on between the generations;

· xenophobia within the family;

· patterns of ethnocentrism, racism, anti-Semitism and violence;

· semantic topoi of myth and family knowledge;

· transmission of authoritarian beliefs and stereotypes;

· impact of social and cultural climate

The case studies we performed reconstructed the development of individual actors in narrative interviews by Grounded Theory (see Strauss & Corbin 1990) in order to discover the mostly implicit but decisive “development paths” and “junctions” which led to relevant “turning points” in their biographies (see Rieker 2002). Thus scientific research might meet the requirements of contextual and structural dimensions of processes of socialisation and upbringing. Those dimensions are relevant for the development of personality characteristics and thus also of moral concepts in young people and should be more in the focus of research even though they may pose different challenges.

Therefore an appropriate way to approach the central issues to be studied here is a qualitative one to reconstruct the biographical development of adolescent individuals (see Schütze 2004; Rosenthal 1993). The reconstructions could be made by means of 27 detailed empirical case studies, including interviews with young people and their parents, grandparents and other adult attachment figures. In order to be able to describe the conditional factors in intrafamilial processes and biographical turning points more precisely and, especially where interfering conditions are concerned, make a more exact analysis, a combination of case-reconstructive procedure (see Kraimer 2000, Fatke 1997) and educational biography research (see Krüger 1997) is used as an interpretative tool.

To analyse those pathways and their junctions that lead to right wing extremism in young people in detail, the biographical interviews with the adolescents were conducted as follows:

· 27 narrative interviews with adolescents of which 6 were female and 21 male (24% female, 76% male). This ratio correlates approximately with the one of young men to women in the Swiss subcultural right-wing scene.

· Average age of the interviewees was approximately 18 years (52% were younger and 48% older than 20 years).

· Nearly one subject in two is member of a right-wing organisation (PNOS, Schweizer Nationalisten, Helvetische Jugend).

· 74% of the subjects have a sub-cultural background (Hooligans, Skinheads/Skingirls including: Blood & Honour, Hammerskins).

· 4 of the 27 adolescents (15%) have experienced foster or residential care.

From a scientific point of view it may seem trivial to point out that there can be a difference between attitudes and actual behaviour. Nonetheless it is necessary because a particular difficulty arises from the fact that the German debate frequently relates to attitudes, orientations and value systems (see, e.g., Fend 1994). However these do not need to be immediately relevant for behaviour per se or may not even adequately describe it. That is why memberships in organisations and subcultural backgrounds are important characteristics of the sample. Furthermore 4 of the young people have a background of foster or residential care (2 males, aged 16 and 24 years and 2 females, aged 15 and 16 years) although we did not specifically look for adolescents who were raised out of home when entering the research filed. They were recruited by distributing flyers in the street and at railway stations, by posting on internet forums and making direct contact on private webpage or through street workers, school social workers and juvenile courts.

4 A generic case analysis: Pathways of “Landser”, aged 16

Before being interviewed, each participant was asked to choose a pseudonym. After the narrative interview (duration: approx. 70 minutes) they were asked to sketch their social network on a white paper. The 16-year-old young man, whose case we would like to discuss as a generic individual case (see Kelle & Kluge 1999) to understand the concept of relevant pathways in narrations, has chosen “Landser” as his pseudonym. This term has several meanings: it was the name of a German soldier in the Second World War, it is the title of a war-glorifying comic magazine and finally “Landser” is the name of a banned right-wing rock band from Berlin. At the time of the interview “Landser” had a sister and his parents had been divorced for a few years. He currently lived in residential care during the week and with his father and his father’s girlfriend on weekends. He is in tenth grade.

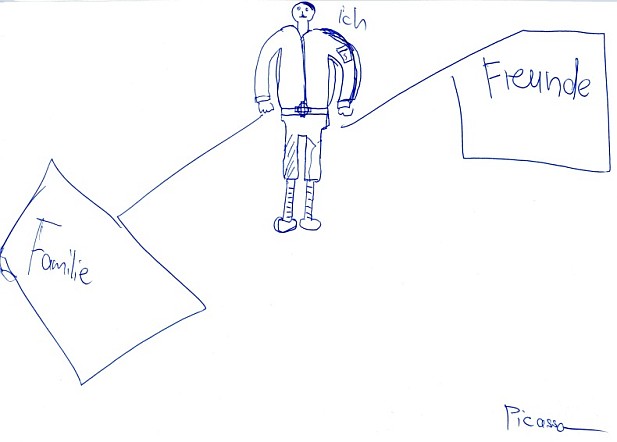

To illustrate his social network, “Landser” painted himself (“Ich”) looking like Hitler wearing a soldier’s uniform. His relevant social network is based on connections to his friends (“Freunde”, top right) and his family (“Familie”, bottom left). It will later on become evident that both the obvious right-wing symbolism and the unbalanced relationship between friends and family in this illustration mean more than visual provocation. With the signature of “Picasso” he tries to relativise his painting for the research in a self-ironic way.

Figure 1: “Landser” (aged 16) and his

social network

To understand “Landser’s” pathway to his right-wing-orientated actions and especially its biographical meanings, we will examine the relevant junctions along his way. This topic-focused structuring of biography is, on the one hand, a result of a chronological analysis of the narrative interview and, on the other hand, a methodological tool to arrange the analysis.

To understand why and how “Landser” sees himself and also why he is active as a right-wing extremist, this genesis is sectioned by the following junctions (Junction 1 to 3) between starting point and arrival point (to present), which result from the analysis of the interview. The following quotations, translated from Swiss German youth slang, in which relevant issues become evident, illustrate the source of this analysis:

Starting point “Having taken some knocks”

“Having taken some knocks” is a biographical topic of unpredictable psychological and physical violence: “I’ve often taken some knocks in my life, not only from my father”.

Domestic violence mainly from his father represents the beginning of “Landser’s” experiences as a victim. He and his sister always had to expect sudden violence without being able to have any influence on father’s behaviour or the situations out of control, as these two quotations show: “He swiped at me full tilt” and “That bloke must’ve been sick somehow, wasn’t he”.

The experience of inexistent protection from others had at least the same effects on further junctions; for example when “Landser” could hear his sister squalling in pain outside the block of flats:

“She must‘ve suffered fucking agonies, I could hear her outside through the whole flat. Sorry but here‘s the flat and I was somehow out there and I can hear it all. Sorry but the whole building must’ve heard it ... That’s strange, isn’t it, that’s hard … Sorry but I was scared/couldn’t help being scared, you know”

First of all, his home – where he actually still lives on weekends – was the place of contingent experiences as a victim: “Because I was constantly frightened of him possibly laying about me, I/for/for no reason he had/he would lose it and what not” or: “For no frigging reason at all”. But comparable experiences on different levels should follow.

Junction 1: “They confined me”

The child protection system reacted late and in a way that was completely incomprehensible to “Landser” and his sister by placing them in a residential care home. They could not understand why they were placed there and not their father as the obvious offender. Expressions and sentences such as “incarcerated”, “They confined me” or “Yes and then they ripped me out of school (and imprisoned me there)” indicate how the young person felt his biographical topic, the experiences of violation, to be repeated.

Out-of-home care also began with an unpredictable situation without any possibility for “Landser” to intervene and without any protection from others such as teachers or peers:

“I was at school, at a case meeting with the staff, I left and afterwards they told me ‘yes we considered that you’re going to a residential care home in summer’ and I just went: ‘boah, that’s not possible’/ like: ‘uwa’! That was/that was like a huge shock”.

Junction 2: “Standing by each other” “It’s a question of pride”

More or less at the same time as he was placed in the residential care home, Landser had his first contacts to a right-wing group. He saw them as a functional equivalent to the family and later on to residential care: “I’d prefer to spend Christmas with my pals instead of my family ‘cause ... Look at it that way, I’m fonder of my pals than my family”.

A main characteristic of this group was an unconditional, existential “standing by each other”. The relevant feature of this group was obviously less his new part as an offender (instead of a victim), but the fact that he was now finally able to act; it was much more the experience of predictable, unconditional, rigid and perpetual trust based on a common idea of pride: “It’s a question of pride”. To receive protection in any situation and to be able to control situations was an extreme contrast to his biographical topic of suffering unpredictable violence without protection from others. For instance, one of his companions went to prison for him when the police found a gun in “Landser’s” jacket: “He went to the clink for me”. So “Landser” re-experienced his Junction 1 (“They confined me”), when his sister and he had to leave home instead of their father, from a new perspective.

This makes clear what “Landser” personally sees behind adopted phrases like “So we stand for the fatherland” or “I would die for my fatherland”. It is less a matter of defending his national identity, but rather of searching for authenticity. Thus everyone who does not share the common and dogmatic ideas of pride is an enemy of his group as well as of his (finally fulfilled) need for control and consistency: “Representing a fascist bloke but hanging out with niggers still (…) I know for sure: those I hate, they are the dregs”.

Junction 3: Turning point: “I own/ have absolutely nothing anymore”

The third junction in “Landser’s” genesis to right-wing extremism could also be seen as a crucial turning point with regard to his biographical topic of “having taken some knocks”. The meaningful issues of this phase of his life become explicit in a situation in his residential care home. It was a biographically well-known situation of sudden and unpredictable violence. Although none of the professionals in the residential care home ever reacted on the right-wing-symbols in his bedroom or even banned them, they took them all out of his room after a (non-political) violent incident between two boys without “Landser’s” involvement. After this reaction his room was nearly empty, no personal items remained:

“Totally, there in the residential home they’ve also thrown everything out, I had my whole room full of pictures, books .., newspaper clippings, photo copies .., they didn’t confiscate the CDs, but just about everything else. When I came back again... after the incident, with a mate who strangled someone unconscious, they went into my room .., they took out everything, books, confiscated everything, (…) They ripped out a few of my German flags and threw everything into a frigging skip, so that I own/ have absolutely nothing anymore. Only the bed, the cupboard, the table and a couch remained for me. Apart from that, my room was as good as empty”.

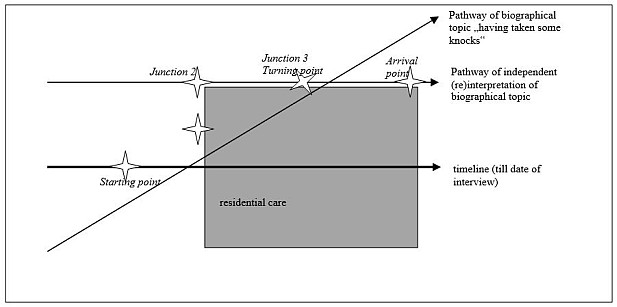

The professionals first did not want to see and afterward did not understand the biographical meaning of “Landser’s” right-wing symbols. They defined them as a superficial and/or political provocation at a time when they needed to react on violence in the residential care home anyway. But this time “Landser” was finally able to reinterpret this repeating experience individually due to his unconditional, existential and constantly remembered (by symbols) belonging to a powerful group. He did not feel involved anymore. In this new interpretation of his biographical issue of “having taken some knocks” those experiences strengthen his self-confidence as an invulnerable part of a group, which is there without being physically present. He can break his biographical topic by taking a new pathway (see fig. 2, Junction 3/turning point):

“Since then, I on/on/only do, what I like to … Yes, actually jump boots are forbidden there but I didn’t give a shit ((quietly)) I’m still wearing them. White shoestring are also forbidden, I’m still wearing them”.

Arrival point

As a reaction to heteronomy and lack of autonomy “Landser” divides people around him up into many enemies and a few but existential friends held together by clear and dogmatic rules of pride. Thus enemies or offenders – recently the professionals at the residential care home – are no longer his enemies; they are the enemies of his group and its symbols. And the group and symbols help him sustain his past life experiences:

“Fuck them all, if they take away my jump boots, I’m gonna get some new ones ... Yes, getting them ... Doing a few ((quietly)) still wearing them. I’ll just do it till/till they give up ... Or till/till I lose ((laughing)). Yes I’d love nothing better than burning the whole bunch down”. How existential his belonging to the right-wing group is, is expressed in his wish to get a swastika-tattoo, which no one could ever take away from him: „That would be wicked ... Later on I want one on my chest ... A fat swastika ((laughter)) ... Yes, that’s truly wicked”.

Figure 2: “Landser’s” meaning of

right-wing extremism: 2 pathways, 3 junctions, 1 turning point

5 Discussion on “junctions”, “turning points” and overall research findings

Methodologically we come to the following conclusion as far as the concept of junctions and turning points is concerned:

· Neither junctions nor (re-constructed) turning points are the same as institutional transitions. They can take place at the same time, but they do not have to.

· Junctions are a crystallisation of biographically continuous topics/subjects and the turning point indicates a relevant and new interpretation and/or action in it.

· Methodologically reconstructions of pathways, junctions and turning points can reduce biographical complexity in a functional and meaningful way.

· To be able to make analyses by using these concepts, high quality narratives are a basic requirement.

Content-wise three pathways with similar turning points could be analysed analytically among the 27 interviewed young people, namely “Violence, disregard and the search for recognition” with “Landser” as a representative, “dissociation by over-adaptation – radicalisation of the values and standards of the social environment of origin” and “Non-perception and the search for experience, visibility and difference”.

Pathway I: Violence, disregard and the search for recognition

The biographies of the adolescents exhibiting this development cluster are characterised throughout by the violation of their physical, psychological and social integrity, when they were growing up as a member of their families. What they experience and how they try to deal with it constitutes a central topic of their biographies and is connected to the familial and intergenerative issues as well as the adolescents’ rightist extremist patterns of interpretation and behaviour. The intrafamilial experience of physical powerlessness and both social and personal disregard entail a fundamental lack of relationships of recognition with their primary attachment figures. One thing that the juveniles who share this development cluster have in common is how they experienced violence from their fathers. Their interactions within the family circle are characterised by conflicted reactions to their person, which are often experienced by the adolescents as contingent, i.e. as something they cannot anticipate. This deficiency, or rather, this lack of habitualised recognition conditions has an effect on the generated ability and disposition for empathy and thus also on the possibility to recognise and acknowledge other human beings in social contexts. Such effects become evident in the deregulated way in which these adolescents commit violent acts as well as in their uncertainty with respect to social relationships. In the process of right-wing group rituals, this biographically acquired disposition is condensed into a habitus.

Pathway II: Dissociation by over-adaptation – radicalisation of the values and standards of the social environment of origin

This development cluster is characterised by the fact that politically right-wing attitudes and behavioural dispositions are already found in the adolescents’ parents, grandparents and other close attachment figures as well as in their cultural environment. The fear of foreign infiltration, the drawing of national demarcation lines, the attribution of cultural characteristics and devalorisations are political issues within the family and part of the family’s culture and history. The adolescents see themselves as an executive power in a widely accepted culture and society. Their political statements and actions earn them recognition and acceptance. There is, however, no unilateral transmission from one generation to the next but rather a discourse about values and traditions of the elders. Unlike Development Clusters II and III, there is no direct link between being right-wing and coping with familial conflicts or socialisation conditions experienced as difficult. Instead, in this development cluster there is a connection to ‘non-extremist’ or ‘hidden extremist’ tendencies. On the level of the biographical developments studied here, there are signs of influence that can be traced back directly to the centre of society and culture.

Pathway III: Non-perception and the search for experience, visibility and difference

This development cluster is not characterised by the experience of physical violence, open and aggressive disregard or contingent actions by the primary attachment figures of the adolescents’ closest family. As in Development Cluster II, that we have called ‘Violence, disregard and the search for recognition’, the absence of communication and direct experience and thus the lack of recognition conditions again has an effect that is biographically relevant. This manifests itself in social uncertainty on the part of the adolescents, albeit in a weaker form where identity-relevant confidence is concerned. The central characteristic is a lack of interaction and communication in the family circle, which are mutually perceived as relevant and meaningful and as significant from a subjective perspective. The phenomenology related to this is multi-layered, ranging from rigid authoritarian patterns of behaviour to mutual ignorance, spatial and temporal absence (by parents or children), unauthentic parenting behaviour and the belief in an unrealistic ideal of how an adolescent should be. The common ground consists of a lack of significant adults who become visible, and can thus be experienced, through their interaction and affective sympathy for the adolescent. Attempts to obtain visibility by means of a deliberate provocation of family issues or inter-generative topics either elicit no reaction at all or affect regulated contact (the adolescents are tested/diagnosed, agreements are drawn up), or it results in explicit ‘non-perception’ as a form of punishment. Achieving visibility through difference and by breaking through the isolation by means of an affiliation (right-wing group, virtual home, ideology) is of significance as a space of experience, in particular for the adolescents belonging to this category.

References

Altermatt, U. and Kriesi, H. 1995: Rechtsextremismus in der Schweiz. Zürich: Nzz Libro Verlag.

Becker, R. 2008: Ein normales Familienleben. Interaktion und Kommunikation zwischen "rechten" Jugendlichen und ihren Eltern. Schwalbach/Ts.: Wochenschau Verlag.

Braunthal, G. 2009: Right-wing extremism in contemporary Germany. New perspectives in German political studies. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Edinger, M. and Hallemann, A. 2008 Rechtsextreme Einstellungen in Deutschland: Messung, Strukturen, Ursachen, Folgen. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Elias, N. 2000: The civilizing process: sociogenetic and psychogenetic investigations. Malden: Blackwell (originally published in 1939 in 2 volumes: "The History of Manners" et "State Formation and Civilization").

Fatke, R. 1997: Fallstudien in der Erziehungswissenschaft. In: Friebertshäuser, B. and Prengel, A. (eds.): Handbuch qualitative Forschungsmethoden in der Erziehungswissenschaft. Weinheim/München: Juventa, pp. 56-68.

Gabriel, T. 2001: Forschung zur Heimerziehung. Eine vergleichende Bilanzierung in Grossbritannien und Deutschland. Weinheim/München: Juventa.

Gabriel, T. 2009: Parenting and Right-wing Extremism – Analysis of the Biographical Genesis of Racism Among Young People. Results of a Swiss NRP 40+ Study. in: SNF (ed.): Right-wing Extremism in Switzerland – An International Comparison. Baden-Baden: Nomos, pp.193-202.

Gilligan, R. 2009: Positive Turning Points in the Dynamics of Change over the Life Course, in: Mancini, J. A. and Roberto, K. A. (eds.): Pathways of Human Development: Explorations of Change. Lanham/Maryland: Lexington Books, pp. 15-34.

Kelle, U. and Kluge, S. 1999: Vom Einzelfall zum Typus. Fallvergleich und Fallkontrastierung in der qualitativen Sozialforschung. Opladen: Leske + Budrich.

Köttig, M. 2004: Lebensgeschichten rechtsextrem orientierter Mädchen und junger Frauen. Biografische Verläufe im Kontext der Familien- und Gruppendynamik. Giessen: Psychosozial Verlag.

Kraimer, K. 2000: Die Fallrekonstruktion. Sinnverstehen in der sozialwissenschaftlichen Forschung. Frankfurt a.M: Suhrkamp.

Krüger, H. 1997: Erziehungswissenschaftliche Biographieforschung, in: Friebertshäuser, B. and Prengel, A. (eds.): Handbuch qualitative Forschungsmethoden in der Erziehungswissenschaft. Weinheim/München: Juventa, pp. 43-55.

Mammone, A., Godin, E. and Jenkins, B. (eds.) 2013: Varieties of right-wing extremism in Europe. Routledge studies in extremism and democracy. London: Routledge.

Möller, K. and Schuhmacher, N. 2007: "... nur ein Suchen nach Anerkennung". Prozesse des Aufbaus rechtsextremer Haltungen im Kontext sozialer Erfahrungen, in: Soziale Probleme, (1) 18, pp. 66-89.

Rieker, P. 2002: Ethnozentrismus und Sozialisation – Zur Bedeutung von Beziehungserfahrungen für die Entwicklung verschiedener Ausprägungen ethnozentrischer Orientierungen, in: Boehnke, K., Fuß, D. and Hagan, John (eds.): Jugendgewalt und Rechtsextremismus. Soziologische und psychologische Analysen in internationaler Perspektive. Weinheim/München: Juventa, pp. 143–161.

Rosenthal, G. 1993: Reconstruction of Life Stories. Principles of selection in generating stories for narrative biographical interviews, in: The narrative study of lives 1 (1), pp. 59-91.

Schütze, F. 2004: Biography analysis on the empirical base of autobiographical narratives - how to analyse autobiographical narratives interviews. Part 1, in: European Studies on Inequalities and Social Cohesion, pp. 153-242.

Siedler, T. 2006: Family and politics. Does parental unemployment cause right-wing extremism? Bonn: Institute for the Study of Labor.

Stock, L., Tausch, C. and Vor, R. (Hrsg.) 2008: Die Welt zu Gast bei wem? Rechtsextremismus, Fremdenfeindlichkeit und Migration in Sachsen, Deutschland und Europa. Berlin: Lit Verlag.

Strauss, A. L. and Corbin, J. 1990: Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques. Newbury Park: Sage.

Westin, C. 2003: Racism and the Political Right: European Perspectives, in: Merkl, P. H. and Weinberg, L. (eds.): Right-Wing Extremism in the Twenty-First Century, London/Oregon, pp. 97-125.

Author´s

Address:

Prof. Dr. Thomas Gabriel

Zurich University of Applied Sciences

School of Social Work

Research and Development

Auenstrasse 4

P.O. Box

8600 Dübendorf 1

Switzerland

Samuel Keller, M.A.

Zurich University of Applied Sciences

School of Social Work

Research and Development

Auenstrasse 4

P.O. Box

8600 Dübendorf 1

Switzerland