Values and Motivations in BA Students of Social Work: the Italian Case

Annamaria Campanini / Carla Facchini, University of Milano Bicocca

1 Introduction

The issue of what motivates students to enrol in degree courses for Social Work is internationally recognized as being of considerable interest, since this motivation is what determines in part the strengths and weaknesses of students setting out on their training (Breen & Lindsay, 2002); it also affects the way social workers will tend to relate to their profession (Stevens et al., 2012).

Several research studies have been conducted in different European countries (Christie & Kruk, 1998; Hackett et al, 2003; Knezevic et al., 2006; Papadaki, 2001; Stevens et al., 2012) to explore the characteristics, motivations, and the values or images of the profession that students have in their respective countries.

The aim of the Italian research team was firstly to describe the main basic characteristics of these students, secondly to identify their value systems and, in particular, the reasons behind their choice of training, identifying both strong points and problematic ones. At the same time the intention was to verify whether this group of young people share the main basic characteristics that emerged from research carried out on all Italian young people (La Valle, 2007) with regard to gender, social collocation of family, territorial context, characteristics which might influence their cultural frames and motives for having chosen this training route, or whether a specific and substantially homogeneous model is to be found amongst those enrolled in this BA course, or if they divide into different typologies.

At the same time, we intended to verify whether any such types of social characteristics have an influence on the motivation the entry to the BA programmes.

The research was carried out in 2005 by using a structured questionnaire distributed to students enrolled in the 1st year of a BA course in social work. The questionnaire, completed by almost all the BA students, involved nearly 2000 students attending social work programs in Italian Universities. In this paper we will present the main findings of this research considering how education has to focus on instilling a critical and self-reflective attitude in students to support the development of the professional role.

2 Social work training and the social work profession in Italy

Before considering the data presented in this research, it will be necessary to offer some brief comments on the training system in Italy and the organizational context of social services. In this country, the training of social workers did not become fully part of the university system until the beginning of the 1990s, first in the form of ‘Schools for Special (vocational) Purposes’ and subsequently through a university diploma course, acquiring the status of a degree course from 2001 onwards (Facchini & Tonaldo, 2010). In accordance with the principles of the Bologna declaration, Italy introduced a national reform of higher education, requiring all university faculties to establish a two-tier system of degrees. With regard to social work there is now a basic degree known as ‘Sciences of Social Work’ and a Masters degree generally termed ‘Planning and Management of Policies and Social Services’. The majority of universities, but not all of them, set a numerical limit to the intake of students for courses in social work by requiring an entrance exam, consisting of questions of a general nature with emphasis on motivation and by taking into consideration the marks obtained by the students at the end of their secondary education. To access the profession of social work, it is, however, necessary to sit a special state examination after the three-year Bachelor’s degree. These state exams are held on university premises but the examiners are made up both of academics and of social workers appointed by the Professional Association of Social Workers (Ordine Professionale). The integration of social work training into the university system within the context of the more general university reform gave also rise to the creation of second-level degree courses, which opened up new career opportunities for these graduates, allowing them access to managerial positions from which they were formerly precluded.

In 2009-2010, 36 Universities offered a BA in Social Work (for a total first-year intake of 4,586 students, of whom 4,120 were women) and 27 offered an MA course (with a first-year intake of 1,125 students, 1,026 of whom women) (www.miur.it).

Alongside changes in the training routes, profound transformations in the system of social services also took place over the past few years. There are several underlying factors for these developments. On the one hand, socio-demographic changes (such as an aging population; transformations in family structure; immigration; changes in the labour market and the increase in precarious work condition) created new demands for social services; on the other hand, changes in institutional orientation, initiated in the 1990s and culminating in the approval of the law on the reform of social assistance (Law 328/00) (Campanini & Fortunato, 2008), have defined new modes of intervention in which public services, the Third Sector and market services interact in a model of mixed welfare provision and de-centralisation with closer attention to client needs (Ranci & Ascoli, 2002; Saraceno, 2002; Ferrera, 2005). Consequently, both the system of social services and the professional profile of the social worker have undergone changes. Social workers in particular face the prospect not only of new forms of contracts with an increase in time-limited contracts and higher job turnover in the services, but also of new models of intervention influenced by managerial considerations (Ferguson, 2008) . In fact, particularly in some regions, social workers have to manage with increased organizational functions and responsibility for 'governance' with consequences for the time they have for the direct work with service users (Campanini, 2011).

3 Research methodology

The data reported in this article relate to a national research project, carried out in 2005[1], involving all 40 BA courses in social work of that year, although 4 did not participate for organizational reasons. All first-year students were invited to take part in the survey, conducted in the first month of teaching, and to complete a structured questionnaire in ‘closed-response’ format.

The questions, which were drawn up in collaboration with lecturers of the BA in social work at the university of Milano-Bicocca, covered different areas: personal details, the type and socio-cultural characteristics of the informants’ family; previous education; leisure activities, friendship networks and membership of associations or groups of voluntary workers; cultural frames (identified through the values considered most important and the degree of confidence placed in different institutions); reasons for undertaking this course of study, and the perceived image of social workers and the sector of service users these undergraduates wished to work with in the future.

The questionnaire was distributed and explained by course coordinators or lecturers during lessons and the students self-completed it anonymously. Students were given further information on the research objectives and the activities of the National Observatory and were told that the data collected would then be processed by the researchers responsible. It was also clarified that the information given would be totally anonymous questionnaire and that students were encouraged to express themselves freely. They could also not fill the questionnaire out, either totally or in part, without this reflecting in any way on them.

The choice to use closed questions was meant to simplify both the students'

responses, and the subsequent data processing. For each question however, several

options were formulated to allow a wide range of alternatives. For example, in

asking students about their motivations for studying social work, a series of

14 possible motivations were presented, offering the opportunity to enter a

value from 1 to 4, corresponding to: 'not at all', 'not very', 'fairly 'and

'very important’. Other questions, such as the one concerning characteristics

which made a suited for social work, were formulated by asking respondents to

assign the answer 'yes' or 'no' to each of the different factors listed.

Finally, for more general topics (socio-cultural characteristics of the family,

previous education, leisure activities, friendship networks and membership of

associations or groups of voluntary workers, cultural frames) it was decided to

use the questions that were formulated for an important national survey on

young people, in order to verify whether and to what extent the social

characteristics and cultural patterns of these students were similar to those

of a population of similar age. In particular, as regards the cultural models,

participants were asked to declare on the one hand how important these models

are for their lives for as many as 20 areas of reference (family, friends ...)

and values (democracy, freedom, good life ...). On the other hand

they were asked what degree of confidence they would place in 12 major Italian

public and private institutions (parliament, municipalities, police, courts,

churches, political parties, trade unions ...). In the first case, the answer

options provided were 'not at all', 'not very', 'fairly' and 'very' important,

in the second, the option was to give these institutions a rating from 1 to 10.

1.893 students replied out of a total of 4.547. This rate of return can be

explained firstly by the fact that two of the courses that were not involved

have a very high number of social work enrolments, equal to over 10% of the

total. A second reason was the fact that on some degree courses attendance is

not obligatory for many lessons and thus some students were not present in the

week when the questionnaire was distributed. The percentage of students who

completed the questionnaire reaches 80-90% on the degree courses where

attendance is obligatory, whilst in the other degree courses it is around

30-40%.

For this reason, our considerations apply to students who were attending the lectures. However, since there are no differences in the responses of students according to whether their class attendance was compulsory or not, we believe that the sample is actually representative of all students taking a BA in social work. Its significance is also confirmed by the way some ‘basic’ variables (gender, age, previous education) correlate with the data on the ministerial website (www.miur.it) and those found by Almalaurea [2] (www.almalaurea.it).

Finally, it seems important to emphasize that although the questionnaire was completed independently and without any control by the teachers, the percentage of respondents was almost equal to the total number of students in the classroom and that, in almost all cases, the non-responses were less than 5%.

We should like to stress the fact that the massive support for the survey is a good indication of the coordinators’ interest in the issues raised; in addition, the fact that very few students failed to respond is a good indication of their own interest in the issues. The data were elaborated by the authors, using the Programme SPSS (PASW Statistics 18).

4 Findings

In this section we will present the major findings of our research. After a description of the socio-anagraphic profile of students enrolled in Social Work courses, data on values orientation and motives for studying social work will be discussed. At the end we will offer a portrait of the characteristics attributed by students to social workers.

4.1 Socio-anagraphic profile of students enrolled in Social Work

Let us first consider the main characteristics of the newly enrolled students.

Basic demographics revealed that female students account for over of 90% enrolments confirming the strong female connotations, common to all western countries (Christie & Kruk, 1998; Benvenuti & Segatori, 2009; Hackett et al., 2003; Papadaki, 2001), of students who set out along a career path in social work, as, indeed, in other caring professions (Heggen, 2008). This female preponderance is confirmed by ministerial figures which, in the year 2005-06, revealed an incidence of female students in social work of 89.7% compared with an average of 54.6% of the student population (www.miur.it).

Secondly, students of social work prove to come from more modest social backgrounds than the majority of university students (Papadaki, 2001). Taking into consideration their fathers’ educational qualifications, it can be seen that 9.3% of fathers are graduates, 42.1% possess a high-school diploma, whilst 48.8% possess at most a lower secondary school certificate. The figures regarding their mothers’ educational qualifications are almost identical, respectively 8.2 %, 42.6% and 49.1%. If, on the other hand, we consider their professions, we find that 12.5% of fathers are managers or free-lance professionals, 2.3% teachers, 31% white-collar workers, 16% traders or craftsmen, 31.8% workmen, 3.3% farm workers, and 3.1% work in other professions. Amongst the mothers, 39.4% are housewives; amongst working mothers, 4.9% are managers and free-lance professionals, 14.3% teachers, 39.7% employees, 13.6% traders or work in the crafts, 20% workers, 2% work in agriculture and 5.7% work in other occupations. In this case it is not possible to compare the results with ministerial figures because there is no information on the social background of students. It is, however, possible to make a comparison with the data found by Almalaurea [3], which confirms a decidedly more modest social profile for undergraduates in social work than for the overall student population: in 3.3% of cases both parents are graduates (as against an average of 8.4%), in 7.9% of cases one parent is a graduate (as against 14.8%), in 41% of cases both parents have an upper-secondary school diploma (as against 45.3%), in 42.5% both parents have a lower-secondary school certificate, as against an average of 29.2%. The results on overall social class are equally significant. According to Almalaurea, 11.9% of students on this BA course can be considered as belonging to the upper middle class (as against a 22.3% average), 25.2% to the middle class (as against 30.7%), 22% to the lower middle class (as against 20.1 %), 33.8% to the working class (as against 23.2%).

There may be various reasons why students enrolled in this BA are collocated in the low-middle classes. The first is because, as mentioned previously, for a long time training in social work took place outside the academic system and consequently the negotiating power and overall social status of social workers was decidedly lower than that of the standard graduate. The second derives from the fact that in order to access the profession of social work three years of study are sufficient, whilst for many other social professions (psychologist, sociologist…) an MA is normally required. The combination of these factors tends to attract more young people from middle-class, or lower middle-class, families than from the upper classes.

Those who undertake training in social work are not only distinguished by socio-demographic features but also by their previous choice of school and their membership of associations.

A considerable proportion of our undergraduates (24.5%) come from ‘licei psico-pedagogici’[4] (high schools specifically oriented towards psychology and pedagogics),

36.7% come from other ‘licei’ and 38.7% come from Technical Schools.

If we compare these data to those collected by the Ministry for Education, Universities and Research on those who matriculated in all BA courses, significant differences emerge in the distribution of the data: in fact, in the year 2005-06, out of the total number of matriculates, only 5.6% came from ‘licei psico-pedagogici’, 44% came from other ‘licei’, 44.5% from Technical Schools.

The evident relationship between the access to this BA and prior attendance of a high school oriented towards psychology, pedagogics and social sciences seems to us to be interesting, because it proves that a fair number of those who embark on training in social work have already developed an interest in these areas by the end of their compulsory education, an interest that is confirmed and reinforced in their choice of university studies. As demonstrated by many studies, those who gain diplomas from these high schools subsequently enrol mainly in faculties such as Psychology, Science of Education and, albeit to a lesser degree, in Sociology.

The fact that students of social work have already developed an interest in the area of social issues is also borne out by their greater participation in voluntary associations. Compared to the 5.2% found by Italian national research on young people, carried out by the IARD (La Valle, 2007), our data reveal that a striking 30.4% were taking part in social voluntary work, and that 19.5% had had the same experience in the past [5].

The data thus show that those who choose their university course with a view to a caring profession, such as that of the social worker, tend to have had some form of previous social commitment, whether this involved an interest in specific subjects of study or whether it implied experience in voluntary work or associations (Mormino, 2008).

4.2 Value orientations

Let us now consider the main features of the interviewees’ cultural frames.

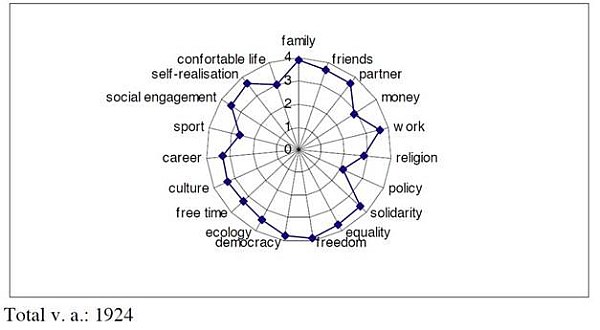

The first important aspect emerging from our data concerns a strong trend towards values of solidarity: as shown in Graph 1, the average score attributed to values such as

‘freedom’, ‘social equality’, ‘solidarity’ or ‘social commitment’ is in fact extremely high; on a 1 to 4 point scale, amounting to, respectively, 3.9; 3.7; 3.6; 3.5. Equally important is the role attributed to self-realization, where the average is 3.7, whilst less importance is attributed to elements such as money, career or a comfortable life, values which record average scores of around 3.

Graph 1. Role attributed to different areas and different values

These figures acquire an even more marked significance when compared to those found in studies by the IARD (Buzzi et al., 2007), from whose questionnaire our items were adapted. For example, amongst the students enrolled in social work, social commitment is considered extremely important by 52.9% (as against an average of 25.5%), ‘democracy’ by 75.8% (as against 60.5 %); ‘freedom’ by 86.1%, (as against 71.4%).

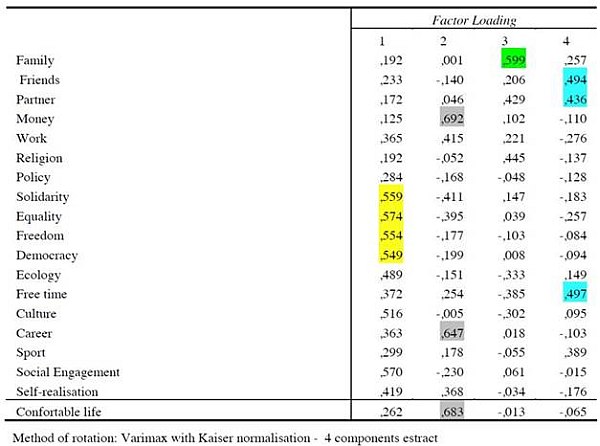

Given the importance of this for our study, it seemed as well to carry out a Component Analysis in order to identify the associations between the various values. As is commonly accepted knowledge, the nearer their value to 1, the more highly they are correlated to that particular factor.

The data shown in Table 1 highlight 4 typologies (which taken together account for 41.2% of the variance).

The first links ‘politically oriented’ values, such as solidarity, equality, democracy and freedom (correlation between 0,55 and 0,57); the second links income, career and a comfortable life (correlation between 0,65 and 0,69); the third identifies a group centring on the strong role attributed to the family; the last is marked by the importance given to aspects such as friendship, love relations and leisure-time (correlation between 0,44 and 0,5).

Table 1. Principal Component Analysis of students values

The first typology identified, which includes those who mark all four ‘politically oriented’ values as ‘very important’, proves to be the largest by far, absorbing 46.1% of the sample. The third and fourth types are also fairly widespread, identifying respectively those centring mainly on the ‘family’ (11.7%) and those who consider all three ‘sociability’ aspects very important (21%). The second type, which comprises students who are ‘income/career oriented’ (2.4%), is decidedly in the minority.

At the same time it needs to be stressed that the importance attributed to solidarity and what Bobbio, the Italian political philosopher, defined ‘warm’ values (‘valori caldi’, Bobbio, 2001) does not develop into an interest in the actual political dimension and does not normally assume a religious connotation, either. Again, using the 1 to 4 point scale, the value attributed to ‘politics’ is the lowest of all (2.1), only slightly greater, but nonetheless modest, than that attributed to religion (2.8). In this case, however, a notably high degree of polarization is recorded between those attending parish groups, amongst whom religion acquires great importance, and those who do not attend them and attribute very slight importance to it.

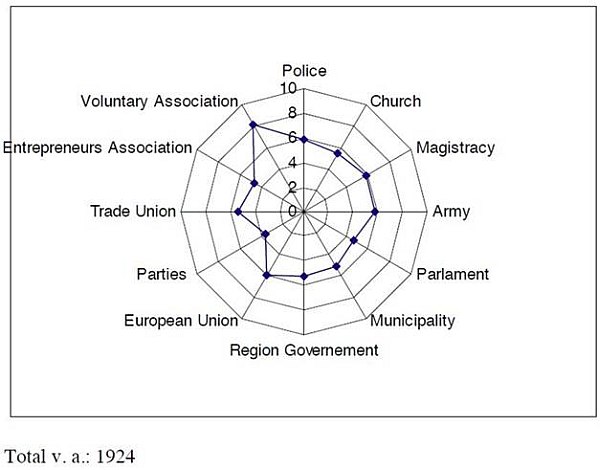

The very slight role attributed to ‘politics’ is strongly confirmed by figures relating to the confidence not only in political parties but also in Parliament, the Municipality and the Regional authorities: on a 1-10 point scale, average values vary between 3.7 for political parties, to 4.5 to 5.7 for the various levels of institutions (graph 2).

Graph 2. Confidence attributed to different Institutions

The points assigned to almost all the other institutions mentioned are only a little higher: they vary from around 5.3-5.6 for Trade Unions and the Church, to 5.7-5.9 for the Armed Forces, the Carabinieri (Policemen) and magistrates. Figures relating to voluntary associations are very different, the average being 8.2, which shows that, with a few exceptions, the students have a great deal of confidence in them (Mormino, 2008).

To sum up, amongst these students we see a combination of the important role attributed to ethical issues and social justice generally underlying the political dimension and just as strong a lack of confidence in the institutional bodies representing this political dimension, which are seen not only as ‘cold’ (to use Bobbio’s terminology again) but also ‘distant’, if not regarded with mistrust. In particular the lack of confidence in entities such as the Municipality or other local bodies is striking, since they are the main professional contexts for social workers (Facchini, 2010).

4.3 Motives for studying social work

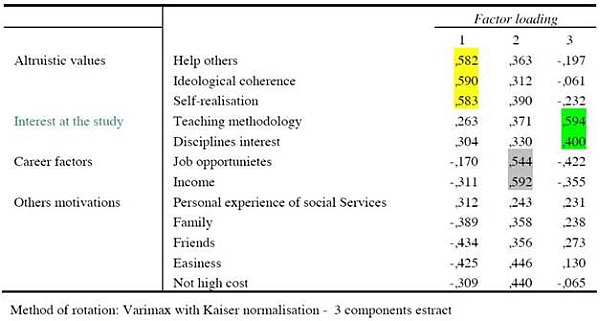

The importance of the dimension of solidarity is confirmed by the students’ motives for matriculating in this degree course. There were far more frequent explicit references to self-realization and ethical dimensions (Shardlow & Doel, 2002; Wilson & McCristal, 2007; Redmond et al. 2008) than found in other studies on the choice of faculty (Cavalli & Facchini, 2001). As shown in Graph 3, motives such as the desire to ‘help others’ or coherence with the students’ ideological convictions record average scores of 3.8-3.6 on a 1- 4 point scale. The role attributed to interest in the subjects studied and teaching modes is also considerable (with average scores of 3.5 and 3.1), whilst a less important role is attributed to elements such as the chance of finding a job or, to an even lesser extent, the expected salary (with average values of respectively 2.8 and 2). Lastly, hardly anyone mentions factors such as easier studies or the role played by friends and family.

Graph 3. Motives for studying Social Work

As was mentioned previously, the profession of social work is not associated with a high income or well defined social status, and the social image of the profession is not necessarily positive (Allegri, 2006). It is therefore easy to understand not only why only few students mention income or the chance of finding a job as reasons for matriculation, but also why the influence of family and friends is so slight here.

In this context, what is worthy of interest is the fair percentage of those who refer to personal knowledge of the services: since this motivation is decidedly more frequent amongst those who belong to voluntary associations than it is amongst others[6], it is

reasonable to suppose that knowledge of the services is linked to the practice of voluntary work and not to being or having been users of them.

Also in this regard, there are very slight territorial differences or differences linked to the social condition of the family of origin or between men and women. On the whole, these data thus seem to confirm that the choice of enrolling for this particular BA course is the fruit of life paths and identity models that are very ‘specific’ compared to the average and this is particularly true for the male students[7].

In this case, again, it seemed advisable to carry out a Component Analysis to identify associations between the various motives.

As emerges from Table 2, the analysis identifies three main typologies (which taken together account for 42.7% of the variance). The first embraces motives that might be characterised as altruistic/identity-linked: ‘helping others’, ‘ideological coherence’, ‘self realization’ (correlation between 0,58 and 0,59); the second links are ‘job opportunities’ and ‘income’ (correlation between 0,54 and 0,59); and the third links are ‘teaching methodology’ and ‘interest in the subject areas’ (correlation between 0,4 and 0,59).

Table 2. Principal Component Analysis of motives for studying social work

The first typology, including those who consider all three motives in the first group ‘very important’, covers a significant 42.8% of the students; the second, including those who consider aspects linked to the educational route very important, accounts for 23.1%. Lastly, the third, embracing all those who consider aspects linked to income and job opportunities very important, accounts for only 2%.

The picture emerging from these figures is basically similar to that found in other recent research studies carried out both on students in other countries (Stevens et al., 2012) and on Italian social workers[8].

At the same time, it is understandable that associations also emerge between the motives

for enrolment and the importance attributed to different aspects of personal life. In particular it was found that motives to do with ‘solidarity’ become even more widespread amongst those who give a lot of importance to ‘politically oriented’ values (55.6% as against the average 42.8%), whilst motives linked to income are decidedly more noticeable in career-oriented students (amongst whom they amount to 15.2%, as against the average 2%).

4.4 Characteristics attributed to the social worker

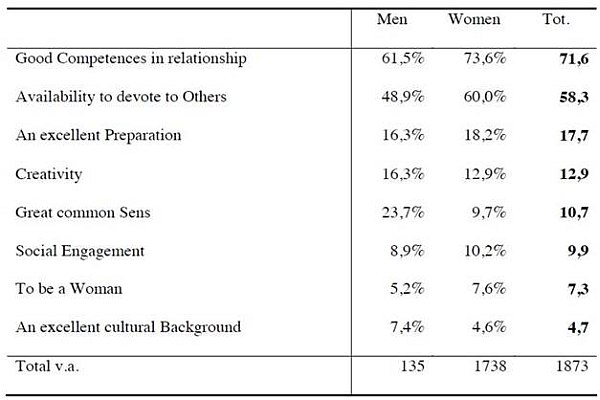

Data relating to factors identified as denoting a predisposition towards the profession of social work is also significant (table 3).

Table 3. Features considered important in a social worker

Above all, despite a strong female presence amongst the above mentioned students, the gender stereotype does not seem to be present in the sense that only 7.4% believe that women are better suited to the profession of social work than men.

The answers regarded mainly ‘the ability to relate to others’ (71.6% in agreement) and ‘openness towards others’ (58.3%), whilst little value is attributed not only to ‘having a lot of common sense’ (10.7%), but also to a ‘specific professional preparation’ (17.7%) or ‘social engagement’ (9.9%). A very slight role is assigned to ‘excellent basic education’ (4.7%).

The gender difference here is only slight, but in this case not negligible: the women more often mention ‘good ability to relate to others and devote care to them’ (73.6% and 60% as against 61.5% and 48.9% of the men, and less the fact of having ‘a lot of common sense’ (9.7% as against 23.7%).

The great importance attributed to the dimension of empathy and understanding rather than to the acquisition of professional competences confirms what has emerged from an exploratory survey on four European countries (Hackett et al, 2003) and seems to reveal characteristic features specific to those who set out on a training course in social work.

It seems, then, that in the collective imagination of the young matriculates there is a

deeply rooted component linked to aptitude and mission, and to a much lesser extent the component that instead was emphasized from the moment this training programme was set up, of gaining adequate professional competences. In this context, the scarce consideration for social engagement, which was, on the other hand, a declared value and actually put into practice in voluntary work by a great many matriculates, appears to be symptomatic. The discrepancy seems in fact to bring to light a greater propensity for individual relationships with people in situations of need and difficulty, rather than an orientation towards intervention based on the collective dimension of social needs. Two considerations might be appropriate. Firstly a substantially traditional, reparatory, individually-based vision of social service seems to emerge, in which solidarity as a value is expressed through a relationship based on individual help rather than leading to solutions or at least interventions of a collective, structural nature (Gilligan, 2007, Stevens et al., 2012). Secondly, this result is affected by a basic lack of confidence in political institutions and the institutional forms of representation mentioned previously.

5 Limitations of the research

Whilst presenting no problems in terms of the representative nature of the sample or the identification of the areas explored, the data reported above would have benefited from a deeper investigation of the issues dealt with, had the survey been accompanied by in-depth interviews or focus groups. These methods would, in fact, have made it possible to achieve a more thorough analysis, on the one hand of the meanings attributed to concepts such as ‘solidarity’, ‘social justice’ or ‘democracy’, and of the basic factors underlying the choice of this training route on the other hand, for example the role that might have been played by critical events in personal or family history, as found in some research studies (Wilson & McCrystal, 2007).

In the same way, interviews and focus groups would perhaps have allowed us to give a clearer account of some important points: for example what is meant by ‘the ability to devote oneself to others’, to which great importance is given, or the reasons why neither an excellent basic education nor specific professional training are considered to be of such importance; finally these methods would have made it possible to sound out the reasons why, according to the students, the profession of social work is so strongly marked by a female presence.

Finally, since it is possible that students not attending classes have values and expectations at least in part dissimilar from those attending, it might be interesting to suggest an on line research, so they too can participate.

6 Elements for reflection

Considering the data presented in this paper in overall terms, some decidedly positive aspects emerge, but also some problematic ones.

Decidedly positive elements are the facts that a value system based on solidarity and ‘civil’ commitment is to be found, but also the conviction that the profession of social work is congruent with these values. The compact picture of values emerging from the data is even more striking if we consider that the differences linked both to gender and to territorial or socio-familial contexts are negligible, whilst most research instead highlights profound differences according to these factors. As is well known, on the one hand post-materialist (Inglehart, 1977) values are to be found more in urban contexts, in more economically advanced regions and amongst young people from educated families; on the other hand, elements such as money and career prove to be more important for men than for women. The fact that this does not occur amongst our students is of great interest, since it suggests that the choice of this course of study and of social work is associated with value systems that are so deeply rooted as to render factors that are normally of great significance less important. In particular, the fact that the men declared a similar or even lesser interest than the women in elements such as money and career seems to indicate that educational and professional choices representing a counter-trend to that typical of their generation are a characteristic of subjects whose identity models vary from those normally adopted by their gender.

Instead, the problematic elements are the one-sided emphasis placed on relationships and an affinity to approaches characteristic of volunteers, to the detriment of acquiring competences from a specific professionalising training route (whose basic structure, the subjects taught and the teaching modes, are, nonetheless, viewed positively).

Of course, as many experts point out, excessive insistence on competences may lead to a ‘technically-biased’ preparation that becomes subject to market forces, oriented towards measuring output and performance (Reisch & Jani, 2012). If, instead, a more holistic perspective is maintained, centring attention on competences, it can offer the opportunity to integrate knowledge, abilities, skills and attitude, thus fulfilling the task of building a profession able to deal with the challenges of contemporary society in an innovative and reflective manner, avoiding social work activities only based on ‘common sense’ and good personal attitude (Hare, 2004).

An initial interpretation of this result might derive from the fact that in Italy training in social work has only recently been incorporated into the university system and the social image of the social work is influenced by the ‘Catholic’ tradition, marked by individual commitment rather than a professional logic. However, this interpretation is compromised by the fact that the central importance assumed by empathy and understanding, even at the cost of acknowledgement for specific professional competences, has also emerged from initial research in four other European countries (Hackett et al., 2003). This phenomenon thus poses certain questions about the cultural models of those who set out on training courses in social work.

Despite the fact that for a hundred years or so social work has existed in Europe and its role in society has been recognized, it does not seem to have acquired the social image of a profession for which a sound theoretical basis is required. Basic education and specific preparation are, in fact, fundamental preconditions for developing the professional dimensions needed to perform the role appropriately and competently. For those who set out on training in social work, it seems that the dimensions of knowledge and know-how are considered to be more a matter of basic predisposition than the fruit of training aimed at acquiring professional attitudes coherent with the principles and values of social work.

Of course, these are initial impressions that precede the completion of a training course: it might thus be expected that in most cases the problematic elements are subsequently corrected (Hackett et al., 2003). For this to happen, however, it is essential not only for the training course to impart specific competences, but to aim at helping students to focus and reflect on their motivation for embarking on this profession, on the fact that individual ‘good will’ is far from sufficient in practice and that reflexivity (Sicora, 2005) as well as specific competences and knowledge are required. It is therefore essential to develop processes of reflection that connect the operational and ethical dimensions of the profession with adequate theoretical models of reference (Campanini, 2009; Kessl, 2009).

The data emerging from this research suggest to those responsible for study programmes in social work that certain key points are often not given enough consideration. Particularly the orientation opportunities offered to students who are planning to choose a university training path, should highlight in a more precise way the functions and the role of the social worker in an attempt to avoid enrolment on the basis of unrealistic assumptions about the profession This attention could also reduce the amount of ‘drop- outs’, a phenomenon that is quite frequent in Italy[9], and ensure that students have more realistic expectations of the demands this profession makes on them.

References

Allegri, E. (2006). Le rappresentazioni dell’assistente sociale. Il lavoro sociale nel cinema e nella narrativa. Roma: Carocci.

Banks S. (2006). Ethics and Values in Social Work. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan.

Benvenuti, P. & Segatori, R. (2009). Professione e genere nel lavoro sociale. Milan: FrancoAngeli.

Bobbio N. (2001). Il dubbio e la scelta. Rome: Carocci.

Buzzi, C., Cavalli, A. & De Lillo, A. (eds.) (2007). Rapporto giovani. Sesta indagine dell’Istituto IARD sulla condizione giovanile in Italia. Bologna: Il Mulino.

Breen, R.& Lindsay, R. (2002). Different disciplines require different motivations for student success. Research in Higher Education, 43(6), pp. 693-725.

Campanini, A. (2007). Social work in Italy. European Journal of Social Work, 10 (1), pp. 107-116.

Campanini, A. (2009), (ed.). Scenari di welfare e formazione al servizio sociale in un’Europa che cambia. Milano: Unicopli.

Campanini, A., (2011), L’assistente sociale, in Carabelli G. & Facchini C. (eds.). Il modello lombardo di Wefare. Continuità, riassestamenti, prospettive. Milano: FrancoAngeli, pp. 217-222.

Campanini, A. & Fortunato, V. (2008). The role of social work in the light of the Italian welfare reform’, in Fortunato V., Friesenhahn G. & Kantowicz E., (eds). Social Work in Restructured European Welfare Systems. Roma: Carocci, pp. 27-40.

Cavalli, A. & Facchini, C. (2001), (eds.). Scelte cruciali. Bologna: Il Mulino.

Christie, A. (1998). Is social work a 'non-traditional' occupation for men?. British Journal of Social Work, 28 (4), pp. 491-510.

Christie, A. & Kruk, E. (1998). Choosing to become a social worker: motives, incentives, concerns and disincentives. Social Work Education, 17 (1), pp. 21-34.

Coyle, D., Edwards, D., Hannigan, B., Fothergill, A. & Burnard P. (2006). A systematic review of stress among mental health social workers. International Social Work, 2, pp. 201-211.

D'Cruz, H., Soothill, K., Francis, B. & Christie, A. (2002). Gender, ethics and social work. An international study of students’ perceptions at entry into social work education. International Social Work, 45 (2), pp.149-166.

Facchini, C. (2008). L’iscrizione tra solidarietà sociale e ‘volontarismo'. Rivista di Servizio Sociale, 1, pp. 19-24.

Facchini, C. (2009). La formazione dell’assistente sociale tra teoria e operatività, in Campanini, A. (ed.). Scenari di welfare e formazione al servizio sociale in un’Europa che cambia. Milano: Unicopli, pp. 163-187.

Facchini, C. (2010). L’attività lavorativa: ruolo dell’organizzazione e centralità dell’utenza, in Facchini C. (ed.). Tra impegno e professione. Gli assistenti sociali come soggetti del welfare.Bologna: Il Mulino.

Facchini, C. & Tonon Giraldo, S. (2010). La formazione degli assistenti sociali: motivazioni, percorsi, valutazioni, in Facchini C. (ed.). Tra impegno e professione. Gli assistenti sociali come soggetti del welfare, Bologna: Il Mulino.

Fargion, S. (2008). Reflections on social work’s identity: international themes in Italian practitioners’ representation of social work. International Social Work, 2, pp. 206-219.

Ferguson, H. (2008). Liquid social work: Welfare interventions as mobile practices. British Journal of Social Work, 3, 561-579.

Ferrera, M. (2005). The Boundaries of Welfare. European Integration and the New Spatial Politics of Social Protection. New York: Oxford University Press.

Frost, E., Freitas, M. J. & Campanini, A. (eds), (2007). Social Work Education in Europe. Rome: Carocci.

Gilligan, P. (2007).Well motivated reformists or nascent radicals: How do applicants to the degree in social work see social problems, their origins and solutions? British Journal of Social Work, 37(4), pp. 735–760.

Hackett, S., Kuronen, M., Matthies, A. & Kresal, B. (2003). The motivation, professional development and identity of social work students in four European countries. European Journal of Social Work, 6 (2), pp. 163-78.

Hare, I. (2004). Defining social work for the 21st century: The International Federation of Social Workers’ revised definition of social work. International Social Work, 47, 407-424.

Heggen, K. (2008). Social workers, teachers and nurses - from college to professional work. Journal of Education and Work, 3, pp. 217-231.

Inglehart, R. (1977). The Silent Revolution: Changing Values and Political Styles Among Western Publics, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Kessl, F. (2009). Critical Reflexivity, Social work and the emerging European post-welfare state. European Journal of Social Work,12 (3), pp. 305-318.

Knezevic, M., Ovsenik, R. & Jerman, J., (2006). Social work as a profession: As perceived by Slovenian and Croatian social work students. International Social Work, 49 (4), pp. 519 -529.

La Valle, D. (2007). Il gruppo di amici e le associazioni, in Buzzi C., Cavalli A.& De Lillo A. (eds.). Rapporto Giovani. Sesta indagine IARD sulla condizione giovanile in Italia. Bologna, Il Mulino, pp. 263-272.

Lorenz, W. (2006). Education for the Social Profession, in Lyons K. & Lawrence S. . Social Work in Europe: Educating for Change. Birmingham: Venture Press.

Mormino, M. (2008). Tempo libero e scelte associative. Rivista di Servizio Sociale, 1, pp. 15-18.

Papadaki, V. (2001). Studying social work: Choice or compromise? Students’ views in a social work school in Greece. Social Work Education, 201, pp. 137-147.

Ranci, C. & Ascoli U. (2002). Dilemmas of the Welfare Mix. The new Structure of Welfare in an Era of Privatisation. New York: Kluwer/Plenum publ..

Redmond, B., Guerin S. & Devitt, C. (2008). Attitudes, perceptions and concerns of student social workers: First two years of a longitudinal study. Social Work Education, 27 (8), pp. 866-882.

Reisch, M. & Jani, J.S. (2012). The New Politics of Social Work Practice: Understanding Context to Promote Change. British Journal of Social Work, 42, pp. 1132–1150.

Saraceno, C. (ed.), (2002). Social Assistance Dynamics in Europe. Bristol: Policy Press.

Shardlow, S.M. & Doel, M. (eds.) (2002). Learning to Practise Social Work. International Approaches. London and Philadelphia: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Sicora, A. (2005). L’assistente sociale «riflessivo». Epistemologia del servizio sociale. Lecce: Pensa Multimedia.

Stevens, M., Sharp, E., Morarty, J., Manthorpe, J., Hussein, S., Orme, J., Mcyntyre, J., Cavanagh, K., Green-Lister, P. & Crist, B.R. (2012). Helping others or a rewarding career? Investigating student motivations to train as Social Workers in England. Journal of Social Work, 12 (1), pp. 16-36.

Trivellato, P. & Lorenz. W. (2010), Una professione in movimento, in Facchini C. (ed.). Tra impegno e professione. Gli assistenti sociali come soggetti del welfare. Bologna: Il Mulino.

Wilson G. & McCrystal P. (2007). Motivations and career aspirations of MSW students in Northern Ireland. Social Work Education, 26 (1), pp. 35-52.

Author´s

Address:

Annamaria Campanini / Carla Facchini

Università di Milano Bicocca

Department of Sociology and Social Research

Via Bicocca degli Arcimboldi 8

20126 Milano

Italy

Tel: ++ 39-3356-2498-97

Email: annamaria.campanini@unimib.it