Different Worlds Within Swedish Personal Social Services. Social Worker’s Views on Conditions for Client Work in Different Organisational Models.

Marek Perlinski, Björn Blom & Stefan Morén, Department of Social Work, Umeå University, Sweden

1 Introduction

During the past twenty years, the Personal Social Services (PSS) in Sweden’s municipalities has moved from a more generalist and integrated way of working to a type of organisation with specialised work groups. At present this integrated organisation model remains only in a few municipalities (Lundgren et al. 2009). This change has been so pronounced that it is possible to talk about a paradigm shift within the PSS. There are several aspects of this shift. One aspect is that there is a discrepancy between the essence of the Social Services’ Act that signifies holism and in the way in which the municipalities put the act into practice. Another aspect concerns the individual social worker’s role and work situation in specialised organisations, entailing an increased number of more (often) superficial client contacts. This aspect is important because a central component in social work, in order to assist clients in changing destructive life situations, seem to be the establishment of supportive relationships with the clients (Knei-Paz, 2009). A third aspect is about which type of trained social worker that should be educated. The Swedish Agency for Higher Education’s latest (2009) evaluation of university social work education programmes, takes a pronounced position for programmes of a generalist character.

The aim of this study is to investigate social worker’s views on how different organisational models (specialised, integrated and combined) for PSS affect their work with clients. This study is one of several within a bigger research project named “Specialisation or integration in the Personal Social Services? Effects on interventions and results”. The project was funded by the Swedish council for working life and social research (FAS).

The aim includes five aspects specified in three questions:

1) What conditions does the organisation of PSS provide for a) assessment of the clients’ problems? b) making appropriate interventions?

2) What conditions do PSS’s economic resources provide for a) assessment of the clients’ problems? b) making appropriate interventions?

3) What conditions do the different organisation models provide concerning the social workers’ possibilities to establish supportive relationships with the clients?

Regarding the concept “supportive relationships”, the researchers have not defined the concept in advance. Rather the social workers, in filling in the questionnaire, have expressed their own apprehensions of the concept.

The research includes all staff in the PSS in three municipalities with different organisation models for their PSS: a specialised organisation, an integrated organisation as well as a “combined” organisation with elements of both specialisation and integration. The specialised organisation builds upon a grouping of problems, but also a grouping of functions as well as age/category grouping, it is in other words multi-specialised. In the integrated organisation all social workers work with almost all of the tasks that arise. In the combined organisation there is a division between functions, such as reception/assessment on the one side and advice and resource on the other side. Additionally, there is a certain grouping by age and problem. At the same time in the organisation there is a formalised consultation, a so-called roundtable, for the purpose of ensuring a holistic view of the work with clients.

The article first presents some studies of the PSS, mostly Swedish ones, that address the connections between different organisation models and client work. Thereafter, there is a description of how the research has been carried out, the data collection method and the sample. Then, in the main part of the article the results of the research are presented, i.e., the social workers’ view of how different aspects of the client work takes form in the different models of the PSS organisations. The article concludes with a discussion that focuses on some of the most striking results.

1.1 Specific traits of the Swedish context

Social work and welfare provision in Sweden is to a large extent part of the public sector. The Swedish public sector, in turn, is divided into a national state area, a county area and a local municipal area. Municipalities in Sweden have an extensive and constitutionally guaranteed autonomy, and an important task is the political and financial responsibility for providing personal social services to their citizens. Social work and especially the PSS in Sweden is regulated by the Social Services Act (2001:453), which is a framework law with few concrete regulations. This act entered into force the 1st of January 2002 when replacing the previous Social Services Act (1980:620). However, much of the basic content in the new act is similar to the former. In addition, since 1992 the Local Government Act (1991:900) provides the municipalities with the freedom to decide how they want to organise the execution of the services.

Consequently, there is a large degree of variation in the 290 Swedish municipalities’ political and organisational models for PSS. However, all these models have certain features in common: they all consist of a political part that sets goals and decides budgets, and administrative and executive managerial part, and a professional part that works directly with clients. The locally elected political parties that govern the municipality designate the members of the social welfare committee. As Sweden does not have family courts, the social welfare committee also (in some instances) makes decisions in specific cases such as restrictions on parental rights regarding the care of children. The professional part may be organised in a wide range of ways. However, in the last two decades there has been a clear trend of abandoning integrated/generic models and instead embracing specialisation.

From the 1980s, that is, by the time the new and integrated Social Services act was introduced, we have witnessed – paradoxically as it may be – an increasing division in different functions, where individual social workers handle a relatively delimited part of the work task. Today, the clearly predominant organisational form is some kind of specialisation, and often problem specialisation, which implies, for example a division between units working with different problems (e.g. drug abuse, monetary benefits, unemployment) or categories of clients (e.g. children, youngsters, immigrants). Nevertheless, specialisation is sometimes mixed with elements of a generic organisation. In 1989 around 51 percent of Swedish municipalities had some form of specialised PSS, but in 2007 the number has increased to 93 percent (Lundgren et al. 2009). Accordingly, generic/integrated organisations are rare and mainly exists in small municipalities. However, this convergence in the organisational forms of PSS is contrary to what was pointed out in preparatory work for the former Social Services Act from 1980, where integrated social work was advocated.

2 Previous research

Swedish research about social services’ organisation is discussed in a research overview by Johansson (2003). From this overview, which spans the years 1990-2000, it appears that during this period there was no research that directly addressed the theme specialisation and/or integration of PSS; the issue has, however, in a number of studies been treated indirectly. In the Anglo-Saxon countries this question has been recognised for a long time.

Challis and Ferlie (1988) have studied a situation similar to the current Swedish one in Great Britain in the 1970s and 1980s. Their study was done in the wake of the introduction of a holistic view in social work education programmes. Paradoxically enough, at the same time organisations that concern themselves with social work started to organise themselves in a specialised way. Among British social workers there was at that time a discussion that questioned the programmes’ general content and lack of specialisation. Challis and Ferlie explain the escape from integrated (generic) social work with social workers’ searching for a clear structure that both creates boundaries/limits for the work one actually does and that establishes requirements for certain specific knowledge.

Bergmark and Lundström (2005) established in their study of 100 Swedish medium-sized municipalities that the previous research about specialisation is modest but one can see that the development clearly goes from integration and a comprehensive view towards an increased specialisation. In Bergmark and Lundström (2007) it was shown that this development ties together with the size of the municipality: the average “generalist municipalities” are smaller than the “specialist municipalities”. It is also evident that the specialised municipalities have made it more complicated for the clients in getting access to the services. This should, on the other hand, be balanced against the advantage that clients meet social workers who are more knowledgeable within a specific area.

In Minas (2005) it is clear from studies of how reception/assessment units function in Swedish social services’ organisations, that there are large differences in how clients are encountered and assessed. The variation largely depends on how the reception/assessment units are organised. The specialised office units are believed to provide visitors greater possibilities of finding solutions, as well as they also often provide a pre-assessment (without a personal meeting), which makes it faster to sort clients out of the system. Wiklund (2006) studied child protection within the PSS based on the influx of reported complaints, organisational conditions as well as structural conditions. When it concerns the theme specialisation/integration, he established, among other things, that assessment in cases of child protection to a great extent take place in organisations that are specialised.

Danermark and Kullberg (1999) refer to a study of drug addicts and point at the risk of falling between the cracks, i.e., between two different functions, in a specialised organisation. M. Söderfeldt (1997) shows that creating a distance to the client within PSS is correlated with specialising. B. Söderfeldt et al. (1997) establishes that an increase in the number of clients and consequently decreased emotional involvement with the individual client gives the PSS staff a temporarily increased possibility to avoid psychosomatic problems. The consequences for the client are not discussed, however. Our own research (Blom et al. 2009) shows that specialisation is not appreciated by clients who are forced to have many contacts with different social workers and poor co-operation between social workers. In one of the field studies (Blom 1998) it is evident that organisations with a strict grouping by function fail in many respects to satisfy the clients’ needs and wishes, particularly when the problems are complex and interwoven.

Morén et al. (2010) has, however, shown that social workers in specialised organisations in informal, spontaneous ways seek co-operation and a holistic perspective. Correspondingly, social workers in integrated organisations seek specialisation and depth, which leads to that some social workers become informal specialists within certain areas.

In summary, the present understanding with respect to organisation models is fairly unclear or rather split; there is support both for specialisation and integration. There are also several different types of specialised organisations, just as the contents of the practical activities can strongly vary in social work – the research object is not unambiguous. There is a lack of comparative studies of how social workers’ practical work with clients and conditions for client work manifest themselves within different organisation models.

3 Material and methods

3.1 Setting and sampling

The study was conducted in three Swedish municipalities with different organisational models within the personal social services: 1) specialised organisation, 2) integrated organisation, and 3) a “combined” organisation with a mix between integration and specialisation. The municipalities were chosen because their PSS-organisations represented highly significant examples in each category. Following Miles and Huberman, (1994), the sample can be categorised as extreme, i.e. different characteristics that, to a varying extent, exists in other individual social services organisations, are concentrated in the sample. The chosen organisations provide aspect-rich real world examples, making it viable to study how processes and results relate to a certain type of organisational structure. The sampling was based on a former study where we had mapped all 290 PSS-organisations in Sweden (Lundgren et al. 2009). From our register with all municipalities, we purposely chose the ones with social services organizations that explicitly and distinctly displayed characteristics concerning specialisation and integration, and a significant example of a “middle-way”. Together, these three organisations represent the present most common ways to organise social work within the personal social services in Sweden. In this text social work is defined as any work task that a social worker conducts, that is related to a specific client, e.g. giving advice, practical support, assessment, material support, social care or treatment.

The specialised organisation was divided into four problem areas: Youth and adults, social (economic) assistance, child and family support and psycho-psychiatric assistance. Within these areas, there was also a certain division regarding age (children, youth, adults) as well as functions like reception, investigation and treatment. Within the integrated organisation there was no organisational division at all, and so all social workers handled all occurring tasks. The combined organisation was basically specialised in different functions; reception and investigation at the one side and interventions (treatment) at the other side. Within these areas there was also a certain division in age and type of problem. At the same time there was a pronounced organisational idea that all client work should build on a comprehensive view paying regard to the need of the client. In order to ensure such a comprehensive view, there was a function built into the organisation called ”the dialogue table”. In this forum social workers from the different functions, reception/investigation and treatment, as well as the clients, were expected to participate.

3.2 Data collection

For data collection an Internet-based on-line survey was used, where each respondent had a unique log-in. The questionnaire included 133 questions. The majority of the questions could be answered by marking one of the answer options, while other questions were open questions, which allowed relatively long written statements. The writing space for answers for open questions was up to 450 characters.

3.3 The completion rate

Data collection was carried out during the spring 2008. Two e-mails with reminders were sent, and once supervisors reminded their staff about the survey. A total of 249 social workers answered the questionnaire, which corresponds to two-thirds of the possible respondents (N=377). A response rate of 66 percent must be considered as satisfactorily high. The response rate was distributed like this: 60.4 percent of 225 employees in the specialised organisation, 77.6 percent of 116 in the combined organisation and 63.9 percent of 36 employed in the integrated organisation.

3.4 Respondents’ age and anciennity

The combined organisation and the integrated organisation are dominated by personnel who are 47-50 years old, while the specialised organisation is dominated by employees who are 40-43 years old. In addition the age span is wider in the specialised organisation so that relatively young and older personnel are mixed. Possibly it means that this organisation is considerably larger and has a greater staff turnover. The consequence is recruitment of new and especially younger staff in that organisation. Analyses of the period of employment show that staff in the specialised organisation on average have a substantially shorter anciennity or work experience within PSS, than staff in the other organisations.

3.5 Limitations of the study

This study is about social workers’ views on conditions for client work within different organisational models. It concentrates on internal circumstances, such as economic resources, workload and division of functions. Consequently, the study does not include contextual conditions, such as demography, institutional environment, geographical location.

4 Analysis

The study includes both quantitative and qualitative data. The result builds upon four different forms of analysis that include both quantitative and qualitative methods. By way of introduction, multiple correspondence analysis (in the form of a map) is used to illustrate the entirety of the relationships between all individual variable values in the quantitative material. Thereafter, the quantitative data are analysed in bivariate cross tables with the organisation model as the independent variable. As a third method, a thematic coding of the social workers’ written statements is used. Finally, these thematic statements are connected to both organisation model and to measurements of the social workers’ actual work situation. For the sake of clarity, further information about the methods of analysis are provided in connection with the presentation of the results.

4.1 The social workers’ view on the conditions for working with clients

The analyses for the five different aspects that relate to conditions for working with clients are presented in the following section. These aspects, gathered in three research questions, are:

– PSS’s organisation as a) a condition for an appropriate assessment of the client’s problem, b) making appropriate interventions.

– PSS’s economic resources as a condition for a) an appropriate assessment of clients’ problems, b) making appropriate interventions.

– The social workers’ possibility, in their current work situation, to establish supportive relationships with the client.

The analysis is presented in stages. First, in the form of a multiple correspondence analysis, thereafter as cross tables and finally as a thematic analysis of written statements.

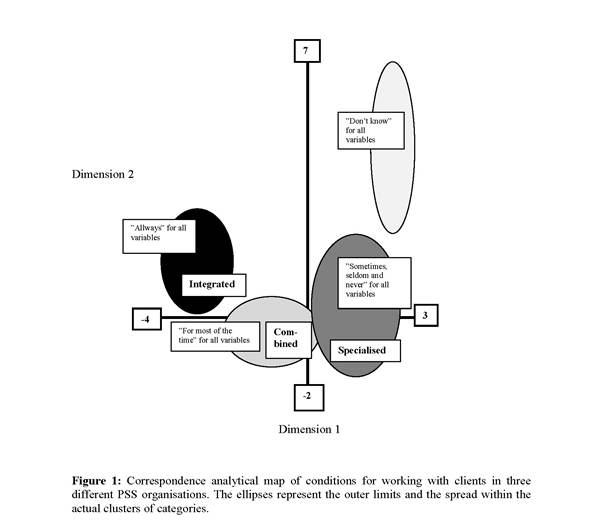

4.2 Map of organisational and economic conditions

Known through Pierre Bourdieus’ work (1984) the correspondence analysis is particularly suitable for searching for patterns in data material. Basically it is a statistical tool for an inductive approach. As Benzecrie (1969) argued, such patterns are difficult to discover with the help of a conventional hypothetico-deductive approach. The correspondence analysis uses an algorithm that treats the variable values, regardless of levels of measurement, as separate categories (i.e., nominal scale). Eventual patterns in the material are represented graphically in a multi-dimensional space, in a way that places categories that are divided by the same units (in our case social workers) as close as possible to each other in a co-ordinate system. Correspondence analytical models simultaneously aim for optimal spacial separation of categories. Our data are represented in a two-dimensional system: Such a map shows the entirety of the connection patterns that are shown in Tables 1 and 2 further on in the article. The correspondence analysis includes the five aspects of the conditions of working with clients that have been stated above. An introductory presentation of the variables that answer each respective aspect is shown in Tables 1 and 2 further on in the text.

The map shows that the integrated organisation distinguishes itself by its members belonging to the category “always”, regardless of which variable one takes into account. The two-dimensional space is clearly split in two organisation models because both the combined and the specialised organisation are fairly similar to one another with regard to the studied aspects. The map, however, suggests that the staff in the combined organisation are somewhat more positive in their judgement of conditions. It is also among the staff in these organisations, especially in the specialised, that the categories “never” and “don’t know” occur.

Paradoxically enough, what appears as a lack of opinion (i.e., “Don’t know”) de facto can be an opinion or an expression for a cognitive state, which can be understood against a background of circumstances that shape these opinions. In this study, ”don’t know-answers”, are interpreted as an expression of individual social workers in the specialised organisation having a work situation characterised by relatively large insecurity concerning fundamental conditions for working with clients. In other words, some individuals find it difficult to evaluate central aspects of his/her own work situation.

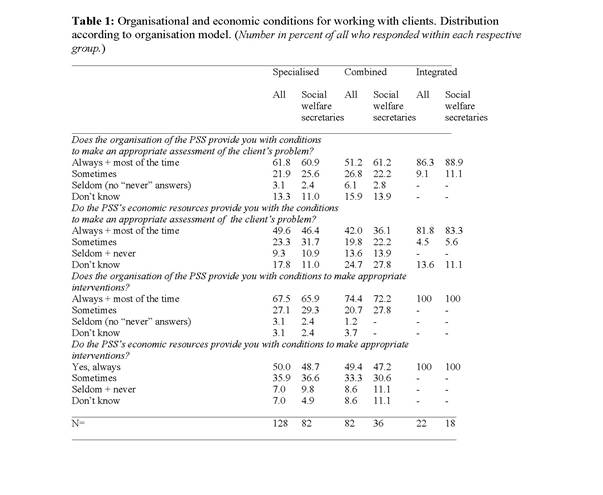

4.3 Bivariate analyses of the organisational and economic conditions

Table 1 shows analyses of the variables 1 to 4 listed against the PSS’s organisation model. The table does not include the relationship aspect that is analysed in the next section. The analysis is divided into two parts: one part includes all social workers at each respective PSS, the other part only includes social welfare secretaries. The reason is that the social welfare secretaries make up a key group of employees in the PSS. Social welfare secretaries is an official term describing a sub category of social welfare officers in Swedish municipalities that exercise public authority under three core laws (Social Services’ Act (SoL) and laws regulating the care of alcohol and narcotic abusers (LVM) and the care and protection of youth (LVU). Almost all social welfare secretaries have academic degrees in social work.

In total 60.2 percent of the respondents have positions as social welfare secretaries. The number of persons with such positions vary depending on organisation model and is highest in the integrated and specialised organisation, 78.3 and 67.2 percent, respectively, and lowest in the combined organisation (44.4 percent).

Table 1 shows that almost all of the social workers in the integrated organisation experience that they always or most of the time have all four aspects satisfied.

When it concerns the specialised and the combined

organisation the answers are more diverse and include important percentages of

social workers who sometimes, seldom or never experience conditions that are

satisfied. Even the number who state that they don’t know is relatively high.

When it concerns the specialised and the combined

organisation the answers are more diverse and include important percentages of

social workers who sometimes, seldom or never experience conditions that are

satisfied. Even the number who state that they don’t know is relatively high.

5 Organisation and establishment of relationships with the client

5.1 A quantitative picture

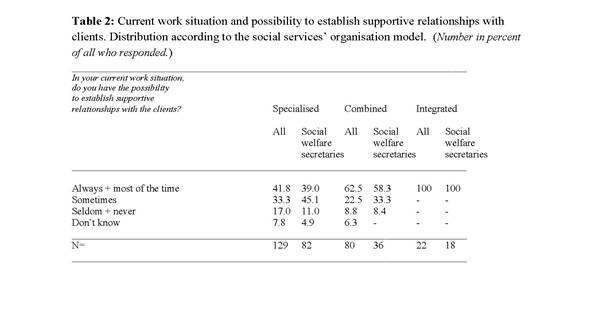

In earlier studies we have pointed to relationships’ fundamental importance for working with clients within PSS. We have also discussed that creating a relationship is an essential professional skill (Perlinski et al. 2012). Assumingly the way in which a PSS is organised should affect the social workers’ possibility to establish supportive relationships with their clients. A specialised organisation where the social worker meets many clients solely based on a limited aspect of the client’s situation can be assumed to provide less space for creating relationships than in an integrated organisation. Even the relationship’s importance for the handling of an individual client task can be expected to be less prominent.

Table 2 shows that there is a clear tendency among social workers in the specialised organisation to judge their possibility to establish relationships as small. One-third answered that one can sometimes establish supportive relationships with the client. Seventeen percent believe that they seldom or never have such a possibility. In addition the proportion of those who are uncertain is relatively high. This tendency is even stronger among the social welfare secretaries in the specialised organisation. The pattern of answers in the integrated organisation stands in direct contrast to the specialised. There, all of the respondents answered that they most of the time or always can create client relationships that are supportive. The combined organisation model appears as a variant of the specialised, even if the social workers state somewhat greater possibilities to establish supportive relationships.

Again, there is a striking division between the

integrated organisation and the two others. Moreover, the latter are relatively

alike one another.

Again, there is a striking division between the

integrated organisation and the two others. Moreover, the latter are relatively

alike one another.

5.2 A qualitative picture

The respondents had the possibility to write comments to their answers at the questions that Table 2 is built on. There were 122 persons who wrote comments in more or less detail with relevance to the context. Seventy of these persons (57%) work in the specialised organisation, 39 (32%) in the combined and 13 (11%) in the integrated. These qualitative data have a high information value, and contribute to an in-depth picture of what social workers view as conditions and obstacles for establishment of relationship with clients.

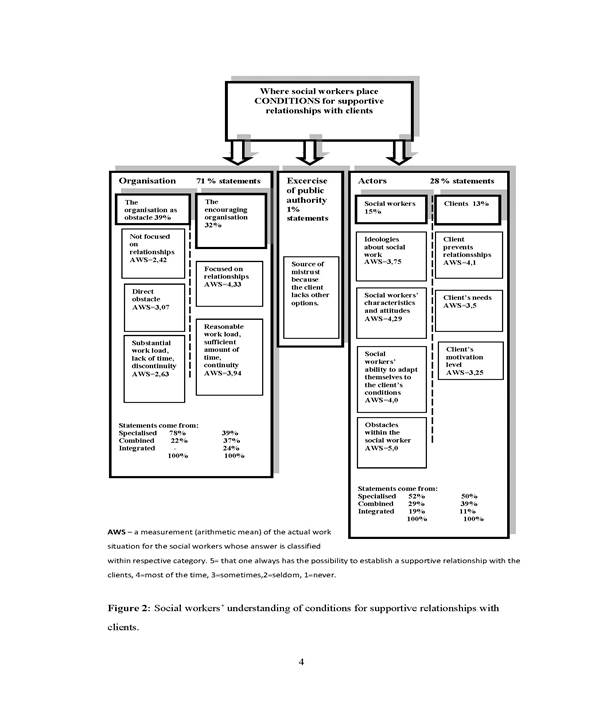

The statements were coded and grouped thematically (Kvale, 1997). Five theme categories could be distinguished: 1) organisation as obstacle, 2) the encouraging organisation, 3) exercising of public authority, 4) social workers, 5) clients. Each theme category includes in its turn a number of sub-themes. In total 142 statements with clear sub-themes have been distinguished.

A common denominator for all of the answers is that they are about conditions for a supportive relationship with the client. The social workers in the studied municipalities place such conditions either in the organisation itself, which is the most common, or on the actors (i.e., social workers and clients). A few social workers name the exercising of public authority, embedded in the work with clients, as a source of mistrust from the client’s side and as a potential power dimension where the client has a subordinate position.

The results of the analysis in a model-like figure are presented in the next section.

6 The social worker’s view on the conditions for a supportive relationship with the client

The majority of all the statements (71 percent) are about different aspects and consequences of the organisational solutions that exist at the respondents’ places of work. Thirty-nine percent of the statements are about the organisations’ negative consequences of working with clients and 32 percent about the positive. Of the remaining 29 percent, 15 percent relate to the social workers’ characteristics including ideological statements about the nature of social work, and 13 percent are about clients’ characteristics and needs. Additionally, 1 percent is about the exercise of public authority as an aggravating circumstance.

In order to clearly tie the statements to the contexts where the respondents find themselves, in the analysis, we have related each written statement to how the informant has answered the question about the possibility in his/her current work situation to establish a supportive relationship with the clients. It is difficult to present such an analysis in a clear way. Information is, nevertheless, so important that we have used a measurement of central tendency (arithmetic mean), in order to describe the average among the respondents whose statements are included in each sub-theme. In Figure 2 this measurement is called AWS (actual work situation). In that way one can have a rather clear understanding of the respondents’ experience of their work situation. For example, the AWS-value (4.1) in the upper right-hand square in the actors’ category defined by ‘social workers who have provided statements about clients as obstacles’, are persons who believe that they usually have good possibilities to establish relationships with clients. Hence, the statements about clients do not depend on a “that’s just sour grapes-effect” from social workers who have not succeeded in creating good relationships with clients.

The actual work situation must in its turn relate to the organisation model. Figure 2 thus includes relative frequencies that show distribution of the main theme according to organisation model. For example, it is evident furthest down in the organisation category, that 78 percent of the statements about the organisation as an obstacle derives from the specialised organisation. From the integrated organisation, however, no such statements are made at all.

As stated earlier, a minority of the statements (28 percent) are about the social workers or the clients. When they pertain to the social workers, the statements are focused on the profession’s ideological position as well as the attitudes and characteristics that the social workers bear. Here the social workers’ ability to adapt themselves to the clients’ circumstances is also highlighted. In addition the eventual obstacles and limitations that lay with the social workers and not with the organisation are emphasised. There are only 18 statements (13 percent) that are about the client as a condition for the relationship. These statements concern clients creating obstacles or simply refusing to have a relationship with the social worker, just as the client lacks motivation for creating a relationship. In some statements it is mentioned that it is the client’s need that decides whether it is justified to establish a relationship.

A presentation and discussion of main and sub-themes follows in the next section.

7 Organisation

7.1 Theme category: “The opposing organisation”

The first sub-theme is named “Not focused on relationships” (19 statements). This sub-theme is concerned with the fact that the work is organised so that it presumes that the contact with clients is kept to a minimal level. We seldom work with longer contacts and The reception/assessment group has short-lived contacts, are two typical examples of answers within this theme. All statements are from the two organisations with some type of specialisation, 79 percent from the specialised organisation and the remaining from the combined organisation. All respondents within this theme have also answered that in their current work situation they have a limited possibility to establish supportive relationships with clients. Consequently the AWS average is low 2.42.

A similar answer pattern with a nearly identical percentage holds true for the sub-theme that is about organisation as a direct obstacle. Eight answers with this meaning have been submitted. Statements like: With the division of functions it is sometimes not possible to continue a contact despite a good relationship and I have about 150 clients, it is completely impossible to establish a meaningful relationship then, illustrate the meaning of this theme. Seventy-five percent of these statements come from the specialised organisation and the remaining from the combined organisation. Six persons answered “sometimes” to the question about actual work situation, and two answered “seldom” and “never”, respectively. The AWS average, therefore, ends up at a relatively low level 3.07 percent.

Another theme category in the material is about lack of time, substantial workload and discontinuity in contact with clients and is content-wise very much like the previous theme (28 statements). This is thus a relatively frequent occurring theme. Two representative statements are: Work load and lack of time worsen the possibility to achieve a working alliance and Substantial work load nevertheless affects the contact, i.e., that I am not sufficiently available. Again an answer pattern emerges that is very similar to the answer pattern in the two previous sub-themes. Seventy-nine percent of the statements come from the specialised organisation and the remaining from the combined organisation. Seven respondents of 28 believe that they in their current work situation most of the time can establish supportive relationships with clients. The remaining 21 are more negative on that point. The AWS average is at a low 2.63 percent.

To sum up, we can determine that perceptions about the organisation model as hindering supportive client relationships occur mainly among social workers in the specialised organisation and to a certain extent in the combined organisation. Specialising, in both the grouping of functions and grouping of problems model, appears in the answers as the organisational factor that most limits supportive client relationships. In addition there is a very clear connection between division of function, substantial work load and lack of time. At the same time it must be added that division of function by certain respondents is viewed as something positive for working with clients (see the following sub-theme).

7.2 Theme category: “The encouraging organisation”

All respondents do not perceive grouping of function as an obstacle for establishment of supportive relationships with clients. To the extent that it is needed because we turn it over to the task force after the finished assessment and I can prioritise my contacts based on the needs that exist, for example, of recurrent conversations or other support, are two typical statements that have been classified as positive organisational conditions and that presume specialisation. Precisely these statements come from within the specialised organisation. They are included in the largest sub-theme “Focused on relationships” (30 statements). These statements are distributed fairly evenly across the organisation models (specialised = 37 percent, combined = 30 percent and integrated = 33 percent). Social workers who have answered in this manner have almost always answered “always” or “most of the time” to the question regarding their actual work situation. The AWS average is relatively high 4.33.

Another theme primarily focuses on that the organisation provides social workers with sufficient time and reasonable work load, as well as makes it possible for continuity in relationships with clients (16 statements). Some typical statements are: I meet the individual client for a longer series of discussions, which means that there is TIME to build relationship and For long contacts over time then a trust and belief develop so that it is overly clear which goal must be achieved. Follow the client through the entire change process. Many of the statements come from social workers who work with such practical activities of the organisation where longer contacts with clients are included as an essential part of the work itself (e.g., work with youths and sheltered housing). The relatively high AWS average of 3.94 indicates that the absolute majority (all but three) have answered “always” or “most of the time” to the question regarding actual possibility to establish supportive relationships with clients. The majority of these statements come from the combined organisation (50 percent) and from the specialised organisation (44 percent).

8 Actors

8.1 Theme category: “Social worker”

The largest sub-theme in this theme category is about the profession’s ideological position and social work’s nature (8 statements). Some of those statements can be rather universal such as: The most is about meetings and relationships, others are directly profession related such as: In the meeting with the client one creates confidence, trust, etc., which can lead to a meaningful relationship that can be fruitful in the form of, e.g., suitable interventions or It is a part of my job regarding a family to be able to establish a supportive relationship. Some of the statements show the vagueness of who actually has the interpretation precedence as in: A supportive relationship is also defined by the client, as much as I know. The ideological statements come from the specialised organisation and the combined organisation, 50 percent each. The social workers in this category have answered “most of the time” and “sometimes” to the question regarding actual work situation, which is mirrored in the AWS average 3.75.

The sub-theme “Social workers’ characteristics and attitudes” is made up of 7 statements. Some of these statements are obviously ideologically loaded, such as: Regardless of the work situation there is always the possibility to use my own power and strength, my empathetic intelligence that exists within myself. To establish supportive relationships is about my own engagement, my own will and trust in people’s unique possibilities to change. Other statements are limited to short assertions, such as: It’s up to me to succeed. It is therefore the social worker’s positive characteristics, will and engagement that can be emphasised. All statements come from people who “always” or “most of the time” can establish a supportive relationship in their work. Consequently the AWS average is high (4.29). The statements mostly come from the specialised organisation (57 percent). Twenty-nine and fourteen percent, respectively, come from the combined organisation and from the integrated organisation.

The next sub-theme is about social worker’s ability to adapt herself/himself and act according to the client’s requirements (4 statements). Those who are in need of a relationship with their social worker (professionally) get it, the others must be left alone, they are not “there yet” or I work with those I work with, as long as we are in agreement that it works well, may represent this sub-theme. All statements come from social workers who answered “most of the time” to the question regarding their actual work situation, which is mirrored in the AWS average of 4.0. Three of the respondents work in the specialised organisation and one in the integrated organisation.

The last sub-theme in this category is about conditions and eventual limitations within the social worker herself/himself (2 statements). These statements come from persons who feel that they “always” have the possibility to establish supportive relationships with the client, whereof the AWS average is 5.0. If I were not able to work on a meaningful relationship then the problem lays more with me than my work situation and organisation and The obstacles that exist, exist within me in that case, that I don’t want to or am able to, but I always have the possibility to take the space that is required. The statements come from social workers in the integrated organisation where one, as a part of the organisational idea, emphasises relationships’ central importance in working with clients.

8.2 Theme category: “Clients”

One sub-theme in this theme category is that clients prevent relationships depending on individual mental status or pure unwillingness (10 statements). Some even mention maladjustment between social workers and the client’s characteristics such as personalities. Sometimes one doesn’t “get through to”. This can depend on the personality of some of us and sometimes an inadequate relationship can even rest with the client, because of fear, scepticism or something else. Some statements express this rather drastically: Often it works well to establish a relationship with the client but at some point one can meet people with such personality disturbances that my knowledge of their problems is not enough to be able to establish a sustainable treatment relationship. Half of the statements come from the specialised organisation. The remaining come from the combined organisation (30 percent) and the integrated organisation (20 percent). The high AWS average (4.1) shows that the statements for the most part come from social workers who always or most of the time have the conditions to establish a supportive relationship with the client.

Another sub-theme focuses on the clients’ needs (4 statements). It concerns both a need in the deeper existential meaning, but even a need in the practical or instrumental meaning, such as choosing the meeting place according to the client’s need. Examples of the deeper needs are: The long-term clients often have small resources, lack of trust towards society, fared badly for a long time. Those clients take a lot of time, are clients for a long time, which in turn leads to that I can create supportive relationships with them and depending on their need for a relationship with me. Some want to have contact often, others as little as possible. Three of the statements come from the specialised organisation, the fourth from the combined organisation. The AWS average (3.5) implies a reasonable possibility to establish supportive relationships with clients.

Finally there is a sub-theme that is about different aspects of the client’s motivation (4 statements). These statements are rather vague in their reference. Furthermore it can be interesting in itself that the client’s motivation or lack of motivation does not appear more frequently in the answers. Three of the statements come from the combined organisation and one from the specialised organisation. The AWS average (3.25) is medium high.

9 Different organisational worlds

This study focuses on how different organisation models affect social workers’ work with clients. The data presented reflects social workers’ views on conditions for clients work in three different organisational models. We have concentrated on some fundamental aspects of social work within the personal social services’: possibilities to establish supportive relationships with the clients, assess clients’ problems as well as make appropriate interventions. Using the results as our starting point we can summarise the answers of the originally formulated questions in this way: neither the specialised organisation nor the combined organisation is able to create economic or organisational conditions for working with clients that are clearly experienced as good. This also holds true for assessment of need, possibilities to make appropriate interventions, such as building relationships. We have determined that a relatively large number of answers point to the organisations’ deficits and even a greater number of answers indicate the staff’s insecurity. In comparison with the answers from the integrated organisation an important difference appears in how staff experience conditions in their work with clients.

The social workers’ own descriptions of possibilities to establish supportive relationships with clients deepen the picture of differences between organisation models, which appear in the quantitative analysis. In other words the qualitative statements point more concretely to which factors that prevent or encourage building relationships. We see first and foremost that it is about the design of the organisation model, work load, time, and continuity. But even aspects such as social workers’ and clients’ characteristics, attitudes, ideologies, etc. appear as meaningful in the context. There are thus several factors that affect the social workers’ possibilities to establish relationships with the clients, but among these the ones that are connected to the organisation model weigh fairly heavy. The qualitative statements are dominated by descriptions from the social workers in the specialised organisation that point to the obstacles that are determined by the organisation itself. All together the results therefore show large differences, to the advantage of the integrated organisation.

A conclusion from the investigation is that we have been in contact with two different organisational worlds. All analyses distinguish the integrated organisation from the other organisation models. Despite that the integrated organisation appears as quite unique, the differences between the specialised and combined organisations are minimal. Considering that there are important structural differences between the specialised and the combined organisations (especially when it concerns the social welfare secretary positions and exercise of public authority) this similarity is fairly surprising.

The striking similarity between the specialised organisation and the combined organisation are not just about those aspects that were investigated in this study, it appears even in several other respects (Perlinski et al. 2009, 2012). Trying to create formalised solutions (compulsory joint meetings between different units) in the combined organisation in order to guarantee a holistic view does not seem to work very well. Above all, social workers lack sufficient time for such meetings, despite that one has reserved a specific time each week.

Our studies show, in line with previous research, that the personal social services have taken on an almost uniform organisational shape. The specialised organisation model currently dominates Swedish PSS. In this ocean there are a few islands of integrated PSS organisations.

Some possible reasons behind PSS’s specialisation as discussed in previous research is: social workers’ attempt at claiming professional power, press from the media and generally putting focus on a special problem/client category, specialisation of certain economic units in the wake of market changes/downturns, the rise of new social problems, isomorphism, i.e., the ambition to imitate other organisations that have a high legitimacy, and finally attempts to raise the level of competence (Lundgren et al. 2009, Bergmark & Lundström, 2007: DiMaggio & Powell, 1991; Meyer & Rowan, 1991; Mintzberg, 1993; Schein, 1993). The previous research in the area does not provide an unambiguous answer to the question of whether one organisation model is more suitable than another. Somewhat simplified, it is possible to say that almost all municipalities are moving in the same direction, but based on fairly unclear reasons.

Despite the relatively clear results from this study we cannot on the basis of a partial study prove that the specialised PSS organisation is generally less suitable than an integrated organisation. However, based on this study it is possible to question the common belief (doxa) in specialisation that is considered to be prevalent in Swedish social services. Our study indicates that social workers’ possibility to assess client’s needs, make appropriate interventions and create supportive relationships with clients are to a great extent conditioned by organisational models.

References

Agency for Higher Education (Högskoleverket) (2009) Utvärdering av socionomutbildningen vid svenska universitet och högskolor. Stockholm, Högskoleverket, Rapport 2009:6

Benzecri, J-P. (1969) ‘Statistical Analysis As A Tool To Make Patterns Emerge From Data’, in: Watanabe, S. (Ed.) Methodologies of Pattern Recognition. New York, London, Academic Press

Bergmark, Å. & Lundström, T. (2005) En sak i taget? Om specialisering inom socialtjänstens individ- och familjeomsorg, in: Socialvetenskaplig tidskrift, 2/3, pp. 125-148

Bergmark, Å. & Lundström, T. (2007) Unitarian ideals and professional diversity in social work practice – the case of Sweden, in: European Journal of Social Work, 10, pp. 55-72

Blom, B. (1998) Marknadsorientering av socialtjänstens individ- och familjeomsorg. Om villkor, processer och konsekvenser. Doctoral thesis, Department of Social Work, Umeå University

Blom, B. (2004) ’Specialization in social work practice – effects on interventions in the personal social services’, in: Journal of Social Work, 4:1, pp. 25-46

Blom, B., Perlinski, M. & Morén, S. (2009) Organisational Structure as Barrier or Support in the Personal Social Services? – Results From a Client Survey. Paper presented at: Dilemmas for Human Services 2009, the 13th International Research Conference “Breaking Down the Barriers”, Staffordshire University, 10 - 11 September 2009

Bourdieu, P. (1984) Distinction. A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste. London, Melbourne, Henley, Routledge & Kegan Paul

Challis, D. & Ferlie, E. (1988) The myth of generic practice: Specialization in social work, in: Journal of social policy, 17, pp. 1-22

Danermark, B., & Kullberg, C. (1999) Samverkan – välfärdsstatens nya arbetsform. Lund, Studentlitteratur

DiMaggio, P. J. & Powell, W. W. (1991) ‘The ironcage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields’, in: Powell, W. W. & DiMaggio, P. J. (Ed.) The new institutionalism in organizational analysis. Chicago, The University of Chicago Press

Hingley-Jones, H. & Mandin, P. (2007) ‘‘Getting to the root of problems’: The role of

systemic ideas in helping social work students to develop relationship-based practice’, in:

Journal of Social Work Practice, 21(2), pp. 177–191

Johansson, S. (2003) Socialtjänsten som organisation. En forskningsöversikt. Stockholm,

Socialstyrelsen

Knei-Paz, C. (2009) ’The Central Role of the Therapeutic Bond in a Social Agency Setting: Clients’ and Social Workers’ Perceptions’, in: Journal of Social Work, 9(2), pp. 178-198

Kvale, S. (1997) Den kvalitativa forskningsintervjun. Lund: Studentlitteratur

Local Government Act (1991:900)

Lundgren, M., Blom, B., Morén. S. & Perlinski, M. (2009) ’Från integrering till specialisering – om organisering av socialtjänstens individ- och familjeomsorg 1988-2008’, in: Socialvetenskaplig tidskrift, 2009, 2, pp. 162-183

Meyer, J. W. & Rowan, B. (1991) ‘Institutionalized organizations: Formal structure as myth and ceremony’, in: Powell, W. W. & DiMaggio, P. J. (Ed.) The new institutionalism in organizational analysis. Chicago, The University of Chicago Press

Miles, M. B. & Huberman, A. M. (1994) Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA, Sage

Minas, R. (2005) Administrating poverty: Studies of intake organization and social assistance in Sweden. Doctoral thesis, Department of Social Work, Stockholm

University

Mintzberg, H. (1993) Structures in fives: designing effective organizations. Englewood Cliffs, Prentice-Hall

Morén, S., Blom, B. & Perlinski, M. (2010) ’Specialisering eller integration? En studie av socialarbetares syn på arbetsvillkor och insatser i tre organisationsformer’, in: Socialvetenskaplig tidskrift, 2010, 2, pp. 189-209

Perlinski, M., Blom, B. & Morén, S. (2009) Om specialisering och integration i socialtjänstens IFO. En totalundersökning av socialarbetares klientarbete attityder och hälsa i tre kommuner. Working paper. http://www.academia.edu/236347/Om_specialisering_och_integration_i_socialtjanstens_IFO._Komplett_version

Perlinski, M., Blom, B. & Morén, S. (2012) ’Getting a sense of the client. Working methods in the personal social services in Sweden’, in: Journal of Social Work, published online 13 February 2012, pp. 1-25

Social Services Act (1980:620)

Social Services Act (2001:453)

Schein, E. H. (1988) Organizational psychology. Englewood Cliffs, Prentice-Hall

Söderfeldt, M. (1997) Burnout? Proceedings from Socialhögskolan 1997:2. Lund, Lund University

Söderfeldt, B., Söderfeldt, M., Jones, K., O’Campo, P., Muntaner, C., Ohlson, C-G. & Warg, L-E. (1997) ‘Does Organization matter? A Multilevel Analysis Of The Demand-Control Model Applied To Human Services’, in: Social Science & Medicine, Vol. 44, No. 4, pp. 527-534

Wiklund, S. (2006) Den kommunala barnavården. Om anmälningar, organisation och utfall. Doctoral thesis, Department of Social Work, Stockholm University.

Author´s

Address:

Marek Perlinski / Björn Blom / Stefan Morén

Umeå University

Department of Social Work

SE-901 87 Umeå

Sweden

Tel: ++46 90 786 71 86

Email : marek.perlinski@socw.umu.se / bjorn.blom@socw.umu.se / stefan.moren@socw.umu.se