Positions of Social Workers’ Views About Residential Care for People with Dementia[1]

Zuzana Havrdová, Jiří Šafr, Ingrid Štegmannová, Department of Management and Supervision in Social and Health Organizations, Faculty of the Humanities, Charles University, Prague

1 Introduction

There is an on-going discussion amongst experts in social work about the threat to the identity of social work as a profession, about its role in society being called into question and about the best way to justify the economic and social support given to the field without allowing it to succumb to neo-liberal agendas (Lorenz, 2007; Chytil 2007; Noble, 2004). Gray and Fook (2004) emphasise the need to unify the terms in which social work is discussed, which will ensure it is not left out of future economic scenarios: “We need to find meaningful and persuasive ways of packaging what we do to ensure we do not become marginalised in new economic environments” (ibid. 638). Repkova (2011) suggests to avoid discussions about the identity of social work and to show, instead, its benefits for society. The present study aims to provide another step in that direction.

The most important part of a social worker’s job in the Czech Republic is in social services. In the last 20 years, this field has undergone a radical change in quantity as well as quality. Before 1989, there were only a few alternatives to institutional care and these were managed by the state. At present, however, there are more than 30 kinds of social services and a whole range of care providers. Most of the providers are non-governmental, non-profit organisations (civic associations, charities and foundations and church organisations), which mainly provide out-patient and field services. Furthermore, new professions have appeared and are searching for an opportunity to define their role. Residential services are the most costly kind of services; they are often provided within state-funded organisations set up by municipalities and regional governments. It is especially important for these organisations to fully legitimise the role of social work and social workers.

The social services reform launched after 1997 was modelled on trends in other European countries. In 2002, the Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs introduced a draft document entitled Quality Standards in Social Services (MoLSA, 2002), which first introduced standards into praxis which were, however non-obligatory. In 2006, after discussions with experts, a Social Services Act was approved. Minimum quality standards and a number of other measures as well as preconditions for the practice of the social work profession were introduced into Czech law.[2] Existing research shows, however, that it has been very difficult for residential facilities for the elderly and people with disabilities to adopt the new approach towards their clients, as required by the reform (Smékalová, Johnová, 2003; the Czech Ombudsman, 2007, 2008, 2009).

It is mainly the individualisation of care, the protection of rights and social inclusion that are most at risk in this kind of environment where approaches are highly dependent on past paths and where power struggles between the professionals concerned may occur. Sometimes residential facilities founded during the communist era still show remnants of totalitarian institutionalist practices, as described by Goffman (1961). The attitudes of employees in residential services as well as their capacity to differentiate between various kinds of approaches and preferences for more individualised care, which is in accord with the requirements introduced by the reform, are therefore crucial. Experience shows that it is social workers who are more ready to adopt new ideas and that they can facilitate the transformation of approaches among other staff (Havrdová, Procházková, 2011). In our view, within the Czech context after 1989, social workers have suitable preconditions for the implementation of individualised approaches to care (we shall discuss this concept later), mainly because of two factors. First, compared to other professions, e.g. medical orderlies, the nature of their work is in accordance with such an approach since the main method is dialogue as well as skills, such as an ability to listen and express empathy. At the same time, these skills have been cultivated by the development of the newly (re)established discipline of social work,[3] namely and in particular as a new curriculum at colleges and universities, which was founded on experiences with models of training and practice in other Western countries. As a new field it caught the attention of young people who were not encumbered by experiences of former times. Since 2006, when the law was introduced, social workers have been employed to a larger extent in facilities of residential care for the elderly. Also, their role in these settings has been gradually shifting towards more influential positions since they often coordinate the implementation of quality standards (i.e. they oftentimes work as quality assurance managers). In the light of this, we find it interesting to study the attitudes of social workers in terms of the requirements of individualised care as opposed to other professionals in the same setting of working teams.

In the Czech environment, social work in social services is still often provided by people without specified educational requirements (Musil, 2008). In addition to these, there is a new generation of social workers who have attended academic courses specialised in social work that were founded after 1989. The position of social workers within the field of social services is defined by law on the basis of the acquired levels of education (higher or university level in social work, which meet the minimum requirements for education), as well as on the requirement that every provider of social services employs a social worker who provides social services to clients and, at the same time, provides supervision to the so-called workers in social services (care staff, i.e. nursing assistants). These generally tend to be workers with lower levels of education, who have taken additional courses in order to be able to work in the area of social services. Furthermore, teams of workers in residential care, particularly in care for the elderly, usually comprise health and associated professionals such as nurses, ergotherapists, medical doctors and professionals from other fields as needed by the client.

In the present study, we focus on the specific area of residential care for the elderly, which is, both highly demanding for workers and an area of social service that is still influenced considerably by the past historical and political context. Our aim was to determine which professions are more likely to internalise the client-centred approach, as required by the standard for quality in social services, i.e. individualised care for the client. Specifically, we were interested in whether the social workers’ attitudes are more orientated in this way than those of other team members. First, we discuss the definition of the concept of the client-centred approach in caring for people with dementia and we show how it was operationalised for the purposes of our research. Using the data from the quantitative survey of staff we then proceed to show the social worker’s point of view and compare it to the perspectives of other members of the team in residential facilities for the elderly. In the conclusion, we discuss our results in view of other possible researches.

2 The client-centred approach with people with dementia

Quality standards in social services define the individualisation of care as a general requirement to create individual plans for providing services according to the needs of the user. This requirement is described in detail in the MANUAL FOR SERVICE PROVIDERS (team of authors 2008), which also contains a number of examples from practice. However, the question of how to apply these requirements to specific target groups of users and in accordance with specific characteristics of each type of service remains the subject of discussions by specialists and is also considered in the process of establishing specific practices in various kinds of facilities and for various teams of professionals. In the ideal case, every member of the team, i.e. workers at different professional positions, participates in these discussions. A more detailed definition of care individualisation for people with dementia still remains a matter of shared experience in individual facilities. Our conceptualisation of the client-centred approach, which amounts to care individualisation for patients with dementia, is, in our research, based on the understanding of quality care for people with dementia as described by Kitwood (1997) in the field of social gerontology, including his concept of “person-centred care”. Brooker (2004) claims that Kitwood’s approach has become a synonym for quality in care for people with dementia in Great Britain. Its characteristics consist of four key elements:

· valuing people with dementia and those who care for them

· working with people with dementia as unique individuals

· seeing the world from the point of view of people with dementia

· providing a positive social environment in which people with dementia can live with relative ease

Nolan et al. (2004) regard Kitwood’s approach not only as “person-centred” but also as “relationship-centred”. These authors claim that Kitwood’s approach does not mention relationships as such even though it does, in fact, include them. The shift of attention from “person” and “individualisation” towards “person in relationships” and “reciprocity”, which are essential for the constitution of “personhood”, is visible in key texts on social work (Houston, 2010).

3 Subject of research, population and procedures

In the spring of 2010, we conducted a research focused on staff attitudes towards care for the elderly and to make an appraisal of different areas of the working milieu, based on a questionnaire survey in the 16 state-funded facilities described above.[4] In view of the fact that the research was carried out in organisations of different sizes, different locations (town vs. country) and among different ages, we divided the various organisations into two basic groups in order to reduce diversity within a single group. The first group represents 11 homes that were founded before the year 2000, whose premises were originally meant to serve different purposes or that were not constructed in accordance with present requirements; these organisations generally have rooms with many beds and did not apply for certification of quality in care for people with dementia. The organisations in this group were called “Organisations T”, as in “traditional” (68% of examined staff work in such facilities). The second group of five homes was called “Organisations N”, as in “newer”, for the sake of simplicity (they comprise 28% of the respondents). These organisations are more modern, they were founded later (the majority after 2000), they are better equipped for providing care to the elderly (the rooms are more modern, with fewer beds, there are common spaces for different kinds of activities, the location is better accessible by various means of transportation) and the management applied for certification in providing care to people with dementia.[5]

In the present study, we analyse a subset of 560 workers in direct care for clients and members of management (in total, 784 workers participated in the research and the average return was 65%). This subset consists of social workers (14%), licensed nurses (28%) and specialists such as ergotherapists or physiotherapists (2.3%), workers in social services, nursing assistants and medical orderlies (57%) and people in managerial positions (2.9%). Women constitute two thirds of the total and 75% of the workers are aged between 36 and 55 years (average age is 43 years) and have been working in the organisation for 10 years on average. More than 80% provide care to clients with dementia frequently (23% work exclusively with people with dementia, 63% often work with people with dementia).

4 Description of the client-centred approach measure

The concept of a client-centred approach introduced above was operationalised in our survey of staff caring for the elderly by several items in a questionnaire. However, the research was conducted for other – primarily practical – purposes; this fact constitutes certain limits for our possibility of operationalisation.[6] Here, we utilise a part of the inventory entitled Working with the Elderly, which contains 16 characteristics of care for the elderly (with special focus on people with dementia) from the point of view of the workers themselves (“How does the facility work?”). This inventory was designed in the first place to enable the self-evaluation of the milieu in residential homes for the elderly by its employees as part of a research focusing on the transformation of care in the facilities. In the present study, we utilise an additional question, the aim of which was to find out what the workers themselves regard as the most important part of care for the elderly. The above inventory of 16 questions was followed by three multiple-choice questions, such as: “Which of the following do you personally think is the most important?” All the answers were related to the purpose of ensuring a certain quality of life for clients living with dementia. We use these answers to measure personal approach preferences (Personal AP) of the workers themselves.

In our conceptualisation, the following five items, out of the 16, represent the client-centred approach: using plans of individual care for elderly clients with dementia; providing opportunities for meaningful activities within the daily programme for elderly clients with dementia; supporting personal choices of the elderly clients within their daily regime; getting to know the life stories of residents with dementia; and adjusting the daily regime to the individual needs of residents. At least two of three choices made had to appear amongst the five items in order for us to classify the worker’s approach as client-centred.

Table 1 shows the distribution of answers to three multiple-choice questions on what a worker in care for people with dementia personally emphasises. It is clear that more than half of the employees in direct care do prefer concepts that are important from the point of view of general humanity and that are in favour of the client (security, respect and kindness of the staff members). However, these concepts do not allow to distinguish the specific “client-centred approach”. Furthermore, these preferences can be regarded as something society demands and hence such answers might be expected since they are self-explanatory and socially desirable. Therefore, more relevant to the subject of our study, which concentrates on the “client-centred approach”, are the answers that contain certain specific elements in support of “personhood” in care and, at the same time, reflect expert knowledge of the field. These answers are much less frequent (although we must take into account the fact that the responses “competed” against each other in order to be ranked as one of the three most important, which is why the majority of the respondents tended to opt for general declamatory answers). The answers of this kind that emerged most often were: providing opportunities for meaningful activities for elderly clients with dementia and adjusting the day regime to the individual needs of residents – about 20% of workers in direct care selected these answers. Together with the use of plans of individual care for elderly clients with dementia, these two answers represent the most frequently demanded “value” in this kind of service (about 17%).

Table 1. Areas enhancing the quality of life of the elderly that are regarded as most important by the worker. Multiple-choice answers to three questions, in percentage.

|

|

N |

% of responses |

% of cases |

|

Ensuring safety for elderly clients with dementia |

310 |

20.3 |

60.5 |

|

Kindness and openness of the staff |

299 |

19.6 |

58.4 |

|

Respect in daily contact with people with dementia |

252 |

16.5 |

49.2 |

|

Opportunity for meaningful activities for elderly clients with dementia* |

95 |

6.2 |

18.6 |

|

Co-operation between social and healthcare professionals while working with residents |

95 |

6.2 |

18.6 |

|

Adjusting daily regime to the individual needs of residents* |

94 |

6.1 |

18.4 |

|

Use of plans within individual care for elderly clients with dementia* |

80 |

5.2 |

15.6 |

|

Comfort, overall pleasant atmosphere in the facility |

74 |

4.8 |

14.5 |

|

Support of individual choices by elderly clients within the daily routine* |

62 |

4.1 |

12.11 |

|

Inclusion of relatives and visitors in the daily routine |

48 |

3.1 |

9.4 |

|

Ability of clients to find their way around the facility on their own |

31 |

2.0 |

6.1 |

|

Residents’ privacy within the facility |

27 |

1.8 |

5.3 |

|

Developing relationships between elderly clients on one ward |

18 |

1.2 |

3.5 |

|

Use of outside experts/services |

18 |

1.2 |

3.5 |

|

Interest in residents’ personal lives and histories* |

16 |

1.0 |

3.1 |

|

Room appearance |

10 |

0.7 |

2.0 |

|

|

1529 |

100 % |

299 % |

Source: Working with the elderly, 2010, workers in direct care and management, N = 512 (8.6% missing cases).

Note: * Items used in the operationalisation of the client-centred approach to care

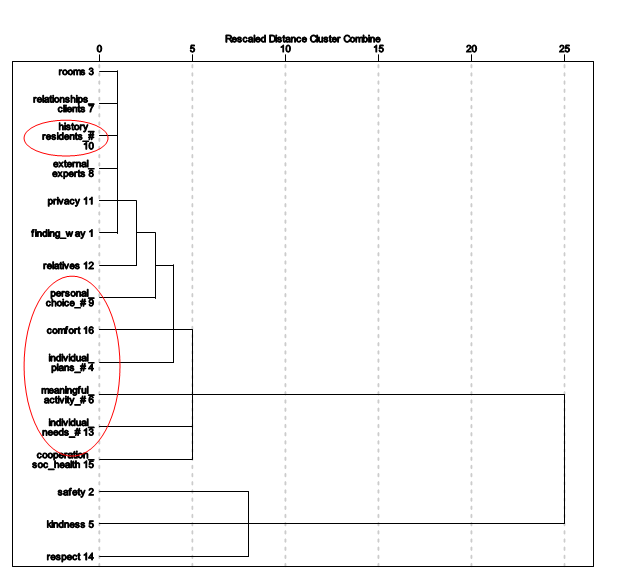

As we have mentioned above, out of the total of 16 possible answers, in our opinion five characterise the person-centred approach to care specifically. In addition, the conceptual base of our operationalisation was confirmed by the result of the hierarchical cluster analysis (see Figure 1). This method classifies objects – here, the variables – into groups on the principle that the variables in one cluster are more similar to each other than to items in other clusters. This takes into consideration the co-occurrence of answer categories thus reflecting distinct images of care methods that different groups of respondents have in common. The individualised and client-centred approach is to be found mainly in the third cluster.

Figure 1. Personal preferences in approach to care for clients with dementia. Hierarchical cluster analysis, dendrogram.

![]()

Source: Working with the elderly, 2010, workers in direct care and management, N = 560.

Note: size distance: squared Euclidian distance, the Ward method

# of items used in the operationalisation of client-approach to care

Taking into account the frequency of responses reached and the limits of the selected measurement method,[7] the presence of at least two items, out of three possible preferences expressed by the worker, reflecting the client-centred approach served as a simplified indicator of this attitude to care. Considering the operationalization to have been applied, we may observe that 12% of workers prefer the client-centred approach in care for people with dementia. These are workers with higher levels of education (namely university and higher education degree holders), and they are younger than the others (between 25 and 35 years). As regards professions, these individuals are usually social workers or members of the management; they prefer this approach twice as often as other professions (see Table 2.). This preference is also most common in the N (newer) type of organisation (17% as opposed to 9%), which are better equipped as far as organisation and general atmosphere.

Table 2. Client-centred approach in work with elderly clients, according to professions

|

|

Client-centred approach |

Other preferences in care |

|

Social worker |

23.7 |

76.3 |

|

Nurse, specialist (ergotherapist, physiotherapist, rehabilitation) |

12.0 |

88.0 |

|

Worker in social services; nursing assistant, orderly |

7.7 |

92.3 |

|

Management |

25.0 |

75.0 |

|

Total |

11.6% |

88.4% |

Source: Working with the elderly, 2010, workers in direct care and management, N = 558

5 The point of view of the social worker compared to other members of the team. Results of regression analysis

The above-outlined results based on bivariate analysis are, however, deficient since the relationships are largely interconnected and interdependent; for instance, younger and more educated people prefer the client-centred approach to care and, at the same time, some organisations employ a younger staff, which is why we will, henceforth, use the multivariate method in our analysis. We shall employ binary logistic regression to compute the odds ratio (conditional probability) that a certain worker will adopt the client-centred approach as opposed to situations when this is not the case.[8] Results show the influence of individual factors, which increase or reduce the net odds of the influence of any other factors. We work with two types of influence: first, characteristics of individual workers where we focus primarily on differences among different professions and the effect of managerial position whereas education and age serve instead as controls; second, in the subsequent model we add the influence of different types of organisations (N-type/T-type) in interaction with the respondent’s professional position within the organisation (the second model also contains all the variables of the first model). In interpreting the data we concentrate on the factual significance of the coefficient; we also use statistical significance (at p < 0.10) as an additional criterion.

Results of the regression models are presented in Table 3. Model 1, reflecting the influence of the characteristics of individual workers, shows that the odds ratio that the worker will prefer the client-centred approach is 1.7 times higher for social workers (as compared to the overall effect of the professions when we consider healthcare workers such as nurses as the reference category).[9] The ratio is similar for people in managerial positions; however, in these cases the statistical significance is exceeded because of the low frequency of occurrence. On the contrary, the chance of preferring client-centred care drops when we take into account workers in the social services (including nursing assistants and orderlies). This is about 50% lower as compared to the figure of the total effect of the worker’s position within the organisation, which is also demonstrated by the negative value of the logit (B). Furthermore, we see that the chance of preferring the client-centred approach in care is highest in workers within the 25–45 age group[10] and notably in those who attained tertiary education (higher-professional or university).

Model 2 adds interaction between the worker’s professional position within the organisation and the type of organisation and it shows that the mechanism described also depends on the overall atmosphere in the home. The odds ratio of the client-centred approach preference is practically the same for social workers as it is in Model 1, which does not take into account the milieu of the organisation. For those in managerial positions and simultaneously working in the new type of homes, however, it is almost four times higher. This result indicates that intensive support for the client-centred approach in care is to be found in managerial positions as well, but predominantly in newly established facilities at which we can assume staff were recruited primarily on the basis of qualification and enthusiasm. It is also important that the logit for people working in social work professions (nursing assistants, orderlies) in new organisations is positive, which indicates that the attitude is somehow positively influenced by the organisational setting. The odds ratio of preferring the new kind of care is 70% higher for these workers than the total effect of one’s professional position within the organisation (in relation to the category of people working in healthcare).

Table 3. Logistic regression of preferring the client-centred approach to care.

|

|

Model 1 |

|

Model 2 |

||||

|

|

B |

Exp(B) |

Sig. |

|

B |

Exp(B) |

Sig. |

|

Worker’s professional position: |

|

|

0.022 |

|

|

|

0.138 |

|

Social worker |

0.52 |

1.68 |

0.061 |

|

0.65 |

1.92 |

0.067 |

|

Worker in social services, etc. |

-0.67 |

0.51 |

0.014 |

|

-0.50 |

0.61 |

0.142 |

|

Management |

0.41 |

1.51 |

0.392 |

|

-0.04 |

0.96 |

0.94 |

|

Higher-professional/ university education |

0.77 |

2.16 |

0.073 |

|

0.67 |

1.96 |

0.130 |

|

Age: |

|

|

0.138 |

|

|

|

0.221 |

|

under 26 |

0.17 |

1.19 |

0.805 |

|

-0.09 |

0.91 |

0.904 |

|

25–45 years |

0.61 |

1.84 |

0.051 |

|

0.51 |

1.67 |

0.107 |

|

Workers in social services, etc. |

|

|

|

|

0.52 |

1.67 |

0.282 |

|

Management * New type of organisation |

|

|

|

|

1.36 |

3.88 |

0.016 |

|

Social worker * New type of organisation |

|

|

|

|

0.61 |

1.84 |

0.304 |

|

Constant |

-2.23 |

0.11 |

0 |

|

-2.50 |

0.08 |

0 |

|

Nagelkerke R Square |

0.096 |

|

|

|

0.125 |

|

|

Source: Working with the elderly, 2010, workers in direct care and management, N listwise = 522.

Note: Figures in bold are p < 0.10; reference categories: healthcare workers; age > 46. Deviation contrast was used for the professional position of workers within an organisation (compared with the total).

It is necessary to stress that even though the model that takes into consideration individual workers’ characteristics explains almost 10% of the variance in odds (Nagelkerke R Square is 0.1; in the second model adding interaction with a different type of organisation, it rises to 0.13), its predictive power is very weak (in total, it is 89%, which is rather efficient; however, it is represented exclusively by the category of those who do not prefer the individualised approach). Nevertheless, the objective of the above analysis was not to use regression equations to “predict” who will tend more towards the client-centred approach in care. We were more interested in determining the importance of the influence of each of the factors and in particular establishing how and to what extent are social workers oriented towards those who are inclined to use individualised care.

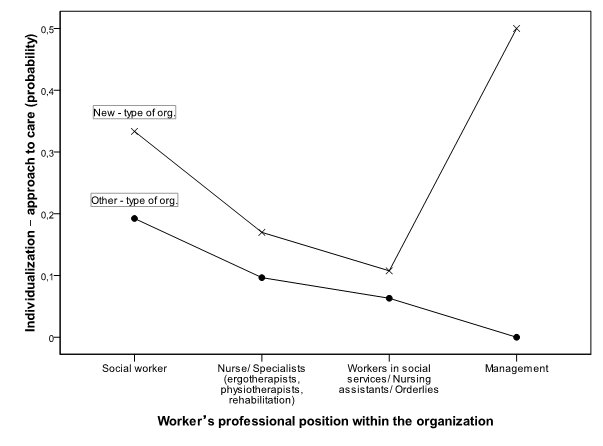

Figure 2 illustrates the differences between various professional positions in two types of organisations, as described above.

Figure 2. Probability of preferring the client-centred approach to care in relation to profession and type of organisation.[11]

Source: Working with the elderly, 2010, workers in direct care and management, N = 558.

It is clear that social workers participating in teams are strong proponents of the new approach both in new organisations and in other types of facilities (T organisations). The milieu of the organisation is significant insofar as people in helping professions, workers in social services, nursing assistants and orderlies employed in new types of organisations are more likely to favour the client-centred approach (even though the difference in preference is minor and insignificant from the statistical point of view). That is true even when the educational as well as the age composition of different types of organisations is being controlled. Finally, we may observe a significantly higher inclination towards the client-centred approach on the part of the management in new types of facilities.

6 Discussion

We conceptualised the individualised approach to care for elderly clients with dementia based on Kitwood (1997) and Nolan et al. (2004) as a kind of approach that respects the personality of the elderly client with dementia and that develops relationships and reciprocity in institutional care. We proposed 16 areas that should be considered by any client-centred care programme and out of which at least five represented individualised care. Taking into account the rather technical limits linked to the manner in which client-centeredness has been pooled in the survey questionnaire and subsequently operationalised in the data, we observed that the internalisation of this approach as operationalised on the part of employees working in facilities caring for the elderly in the Czech Republic remains a minority. Only 12% of respondents opted for at least two of the five areas. If we decided to indicate the client-centred approach strictly by choosing all three items from the set of five desirable ones, then we would find only two (0.4%) workers advocating this approach. To a certain extent, one imperfection of this multiple-choice design is that it does not measure the intensity of the attitude (as was done in the preceding item battery querying on evaluation of the situation in the facility, which includes the same 16 items but which the respondents evaluated with a Likert-type agreement scale). Given that all items were positively expressed and in favour of clients, the measurement method in fact presents an advantage, since it somewhat directly tests the knowledge of principles of the individualised care.

However, our results are restricted in several ways. Firstly, the results can only be generalised for staff in state-funded organisations, because non-governmental, non-profit and private organisations were not represented in our study. Secondly, and this restriction is more significant, the method we used to indicate the client-centred approach is insufficient from the point of view of its operationalisation. As suggested above, the use of multiple-choice questions significantly limits the possible answers and the choice of used items was not directly designed to measure the approach favoured by individual workers (the main objective of the questionnaire Working with the Elderly was to evaluate the situation in each establishment). The main drawback of the method then lies in the fact that it is based merely on declaratory principles and thus it emphasises knowledge or the capability to differentiate between discourses, which is influenced by education amongst other factors. This has also been proven by our results, wherein higher or university education proved to be the most significant factor in the multivariate analysis where effect of professional position was fixed.

On the other hand, we might observe that within the education of both, social workers as well as nurses and workers in social services, emphasis is put on similar values and similar stress is laid on client/patient-centredness (Štegmannová, Havrdová, 2010). It seems then that the differences we found may prove to be a certain “added value”, the specific contribution of social workers in the team. It is not clear, however, what causes it and in what way, if any, it manifests itself in daily care for people with dementia. Therefore, it seems that it would be beneficial to conduct direct observation in specific situations of social interaction between workers and clients. In any case, we are convinced it would be rewarding to supplement the measurement of the client-centred approach with a qualitative study, which would shed light on how the knowledge of this approach is incorporated into everyday routines in care for the elderly and how it (possibly) diffuses in the team.

In as much as a method of observation is almost impracticable in the prevalent praxis, the quantitative evaluation of this approach might be improved by using specialised questions, aimed in detail at the daily implementation of this approach by care workers provide on various dimensions (e.g. contents of communication or knowledge of the client) as well as on related emotions and attitudes. This method is represented for instance by the 36-item Individualized Care Inventory (Chappell, 2007), which was used in our research of care in facilities for the elderly as part of a follow-up study. Research combining qualitative and quantitative instruments is optimal; however, it is rather time-consuming and is often met with little enthusiasm on the part of different social actors who participate in long-term systematic studies. Up to the present, therefore, there have been just a few accomplishments in this area in the Czech environment.

7 Summary and conclusion

Social work must defend its legitimacy by theoretical discussions on the sense and role of social work but more importantly by adopting a clear position within multidisciplinary teams, which will support socially desirable trends and which will, at the same time, be beneficial to clients within the process of improving social services. One such trend reflected in the reform of social services in the Czech Republic is the demand for the individualisation of care. On the road to its implementation, we find it important to follow attitudes as well as praxis that favour the client-centered approach. We have conceptualised this demand in detail for the field of work with elderly clients with dementia as an approach that exercises respect to the personality of the elderly client with dementia and develops relationships and reciprocity (Kitwood, 1997; Nolan, 2004). This is our understanding of the client-centred approach throughout our study in which we investigate its determinants and proponents. Specifically, we were interested in the question whether, within a team, a social worker holds a perspective that is clearly more inclined towards an individualised, client-centred approach, than the perspective of other professions.

The results from the survey conducted in 16 residential facilities for the elderly show that a large majority of those who opted for the client-centred approach were social workers and persons in managerial positions in new organisations (24% and 25% respectively). When all influences are considered together in regression analysis, the odds of tending towards the client-centred approach is the highest among social workers as compared to other professions. On the other hand, the odds of an inclination towards individualised care is reduced in workers in the social services (including nursing assistants and orderlies), who comprise the majority of the staff in direct care for elderly and whose contact with clients in residential facilities is the most frequent. The organisation itself in which the care takes place also plays an important role. The probability that social workers prefer client-centred care is similar in various kinds of organisations; however, in the case of workers in managerial positions, the odds are noticeably higher for “new” type organisations. This might be due to the fact that the process of selection of the managers by the regional authorities in the new type organisations has already been influenced by their dispositions to understand new trends in care. We can suppose that the higher internalisation of the client-centred approach by other staff members in the “new“ organisations is influenced by the organisational culture supported by management, which has the demonstrated stronger inclinations to the new approach. The “new” organisations also are less burdened by the heritage of the past, even by their architecture, and thus they can better focus on fulfilling the goal, which is the well-being of the elderly people in their care.

Based on the evidence, we may observe

that the point of view of social workers in multidisciplinary teams in

state-funded residential services for the elderly clearly tends more towards desirable

reform trends in care for elderly clients with dementia than that of other

professions, regardless of the facility. In the present paper, related to the

benefits of the client-centred approach, we may therefore support a strong

position of social workers within the social services, which increases the

potential for the acquisition of this kind of attitude by other members of the

staff, in particular workers in the social services.

We also observe that it is necessary to continue conducting similar studies

that look into the role of social workers in providing care within the social

services rather than to pursue abstract discussions on the role of social work.

Our findings are based on the applied operationalisation and they depend on the

differentiation of certain terms of discourse, within which the workers most

often find themselves. That is why we recommend concentrating also on the

indicators of the approach to clients in direct social interaction.

References

Brooker, D. (2004) What is person-centred care in dementia? in: Reviews in Clinical Gerontology, 13, pp. 215-222

Chappell, N., L. et al. ( 2007) Staff-based measures of individualized care for persons with dementia in long-term care facilities, in: Dementia, 6, 4, pp. 527–547

Chytil, O. (2007) Důsledky modernizace pro sociální práci, in: Sociální práce/Sociálna práca, 4, pp. 64–72

Gray, M. & Fook, J. (2004) The Quest for a Universal Social Work: Some Issues and Implications, in: Social Work Education Vol. 23, No. 5, October, pp. 625–644

Goffman, E. (1991) Asylums. London, Penguin Books, (1961) (reprint)

Havrdová, Z. & Procházková, M. (2011) Sledování změn v prožívání pracovníků v průběhu zavádění individuálního plánování služby v pobytovém zařízení pro seniory, in: Sociální práce/Sociálna práca, 3, in print

Havrdová, Z. & Šafr, J. (2010) Kongruence v hodnotách jako ukazatel vztahů v péči o seniory, in: Z. Havrdová a kol. Hodnoty v prostředí sociálních a zdravotních služeb. Prague, FHS UK, pp. 85–107

Houston, S. (2010) Beyond Homo Economicus, in: British Journal of Social Work, 40, pp. 841–857

Kitwood T. (1997) Dementia Reconsidered: The Person Comes First. Buckingham, Open University Press

Lorenz, W. (2007) Teorie a metody sociální práce v Evropě-profesní profil sociálních pracovníků, in: Sociální práce/Sociálna práca, 1, pp. 62–71

MoLSA. (2002) Standardy kvality sociálních služeb. Prague, Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs Czech Republic

Musil, L. (2008) Různorodost pojetí, neujasněnost nabídky a kontrola výkonu “sociální práce”, in: Sociální práce/Sociálna práca, 2, pp. 60–79

Noble, C. (2004) Postmodern Thinking. Where is it taking social work? in: Journal of Social Work, 4(3), pp. 289–304

Nolan, M. R., Davies, S., Brown, J., Keady J. & Nolan J. (2004) Beyond ‘person-centred’ care: a new vision for gerontological nursing, in: International Journal of Older People Nursing in association with Journal of Clinical Nursing 13, 3a, pp. 45–53

Repková, K. (2011) Integrovaná tvorba poznatkov v sociálnej práci a pre sociálnu prácu, in: Sociální práce/Sociálna práca, 1, pp. 28–34.

Team of

authors (2008) Standardy kvality sociálních

služeb. Výkladový sborník pro poskytovatele [Standards for Quality in Social

Services]. Prague, Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs Czech Republic.

Available at: http://www.mpsv.cz/files/clanky/5966/4_vykladovy_sbornik.pdf

Author´s

Address:

Zuzana Havrdová / Jiří Šafr / Ingrid Štegmannová

Charles University

Faculty of the Humanities

Department of Management and Supervision in Social and Health Organizations

Máchova 7, 120 00, Praha 2

Czech Republic

Email: havrdova@charita-vzdelavani.cz