Socio-Spatial Approaches to Social Work

Christian Spatscheck, Hochschule Bremen

This essay argues for the consideration of spatial approaches to social work. Spatial sensitivity and reflection allows a multi-level understanding of social spaces beyond individualistic, clinical and single-case oriented concepts of social work. Also, this perspective enables interesting collaborations between social work practitioners and researchers and supports a research based practice.

In the German tradition of social work[1], the idea of social spaces (Sozialräume) became a significant conceptual reference since the early 1990s. Starting with the seminal work “Pädagogik des Jugendraums” by Böhnisch/Münchmeier (1990), a variety of approaches around the concept of social spaces were developed in theory and practice of social work. After some years of discussion the idea of a “social space orientation” (Sozialraumorientierung) can even be regarded an own paradigm in social work (Spatscheck 2009, Kessl/Reutlinger 2007, 41).

The discourse within social work currently follows two different understandings of social spaces. One group of researchers regards social spaces as fields for processes of acquirement, learning and active participation, they developed concepts around youth work, social development and other fields of social work (Deinet 2009). This approach follows the concept to discover, analyse and design social spaces in order to enable processes of social development (Deinet 2006; Deinet/Krisch 2006; Deinet/Reutlinger 2004; Böhnisch/Münchmeier 1990, Kessl/Reutlinger 2007).

The other group of researchers approaches social spaces from a background of community development and the perspectives of modernisation of public welfare institutions, they search for possibilities for improved co-operation, flexibility and citizen participation in the creation of social services (Hinte 2006; Hinte/Lüttringhaus/Oelschlägel 2007; Budde/Früchtel/Hinte 2006; Früchtel/Cyprian/Budde 2007; Früchtel/Budde/Cyprian 2007, Kleve 2007b; 2008).

This text is situated around the ideas of the first group of authors but tries to find connections to the concepts from the authors from the second group. Generally, a “spatial turn” cannot only be found in social work. Social theories around space found their recognition in very different academic disciplines, especially in social sciences and cultural studies (Dünne/Günzel 2006; Bachmann-Medick 2006, 284-328; Kessl et al. 2005).

1 What are social spaces?

Social spaces are regarded as relational orders of (zoological) animals and social goods that are aggregated at common places (Löw/Steets/Stoetzer 2008, 63). Hence they consist of relations that emerge between plural and coincidental placements of individuals and objects.

All spatial approaches implicitly refer to a long tradition of analyses on local networks. In social work, Jane Addams (1860-1935) thought and acted within spatial dimensions in her work in and on the settlements of Chicago (Engelke/Borrmann/Spatscheck 2009, 187-203). She had direct connections to the spatially oriented “Chicago School of Sociology” and their key thinkers Robert E. Park and William I. Thomas (Löw/Steets/Stoetzer 2008, 51).

In earlier debates about social work and social spaces in Germany two spatial models can be found: The model of the ecological zones by Bronfenbrenner and Baacke and the “island model” by Helga Zeiher.

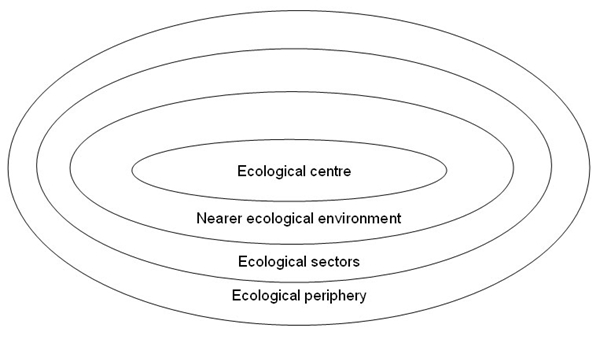

In the model of ecological zones, Dieter Baacke (1984; Figure 1) explained the social embeddedness of the child’s development within local social spaces by referring to the ecological model that was originally developed by Urie Bronfenbrenner (Bronfenbrenner 1979; Grundmann/Kunze 2008, 179). Baacke (1984, 84f.) altered this model to describe the following different forms of social embeddedness:

Figure 1: The model of ecological zones by Dieter Baacke

· The “ecological centre” describes the family and the home of the child as a place where children find the most important and immediate personal references and spend most of their time.

· The “nearer ecological environment” describes the closer neighbourhood that enables the child to find first relationships outside the family in the neighbourhood, the local quarter or the village.

· The “ecological sectors” describe public places like schools, playground, shops or swimming pools. They require a certain kind of social behaviour and therefore demand new skills from the child.

· The “ecological periphery“ is the field of contacts beyond usual routines like holidays, journeys and contacts to other spaces that lie beyond the everyday experience.

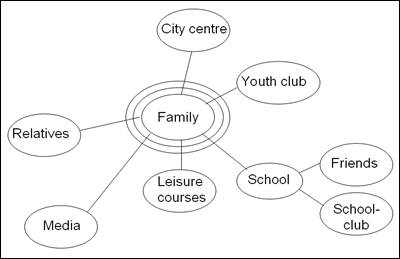

Further research during the 1980s showed that Baacke’s idea of the social embeddedness of children in concentric circles could no longer be held. Studies by Helga Zeiher (1983) initially confirmed Baackes ideas about the “nearer ecological environment”. But beyond, her research showed that nearer zones are no longer experienced in concentric spatial arrangements but rather in segregated worlds that could be better described by the metaphor of connected “islands” (see Figure 2). These islands are located within greater spaces that are merely crossed but no longer fully experienced. Children realise their “island of living” as centre and travel on their way to schools, friends and relatives through other social spaces without feelings of linear connectedness (Zeiher 1983, 187).

Figure 2: The “island model” by Helga Zeiher

The acquirement of new islands happens through a development of loose networks. Supported by increased means of transport and new media, children experience these islands no longer as one connected geographical area.

Based on these two models, a new debate about social work and social spaces has emerged from the 1990s onwards. The key idea of these socio-spatial approaches is the emphasis on interactive connections between inhabitants and their social and ecological environment. These are described by the idea of relationality: Spaces are no longer regarded as absolute entities, nor can they be considered as being completely relative (Kessl/Reutlinger 2007, 27). Instead they seem to be determined by the interaction between inhabitants and their environmental structures.

New ideas about social spaces include the connection between local, regional, national and transnational influences. In this sense, social spaces can be regarded as dynamic fabrics of social and material practices that are (re)produced permanently on different levels of (inter-) action. Following these ideas, social spaces are regarded as double structures with two connected perspectives (Deinet 2007, 113-120):

· The material and objective conditions of life in a certain area. These structures of social spaces can be measured by socio-structural data about the socio-economical situation, habitat and buildings, family structures, educational standards, the frequency of the usage of public services, as well as the identification of problematic social structures and processes of gentrification. Most of the data can be collected through a quantitative research perspective; the top-down perspective and the views of policy-making and administration seem to be central. Sandermann/Urban (2007, 44) call this perspective “socio-geographical and infrastructural” perspective.

· The subjective perspectives of the inhabitants and service users that regard social spaces as their life world (Lebenswelt) and as public spaces that can be designed and acquired. Here the key focus lies on the subjective and qualitative dimensions of social spaces. Behaviour strategies can be explained on the background of individual and group contexts of meaning that build the person’s life world (Lebenswelt) (Deinet 2006; 2007; Deinet/Krisch 2006). Most of these phenomena can be experienced through a qualitative research perspective. Here, the bottom-up perspective of acting individuals and their experiences seem to be central. Sandermann/Urban (2007, 47) call this perspective “acquiremental-theoretical and subject oriented” perspective.

Socio-spatial approaches follow an interactive perspective that tries to focus on the mutual connection of these two dimensions. Social spaces are no static “containers” but relational and changeable arrangements of humans and material goods (Löw 2001, 271; Kessl/Reutlinger 2007, 21). Through the process of “spacing” individuals can acquire material places (Orte), form new relations and create new social spaces (Räume) with own qualities (Deinet 2006, 59). In this understanding, spaces are always socially determined. Therefore, different social spaces can be identified at one geographical place. Social spaces can be altered and also vanish when their producers leave the place. Following this idea, social spaces can be regarded as small and temporary societies on local and regional levels (Kessl/Reutlinger 2007, 23).

2 Socio-spatial working principles

Social work is always carried out in societal and spatial contexts that are influenced by the involved actors. To maintain professional autonomy, it therefore becomes relevant to reflect discourses about spatial order. In current Western societies, especially the following four discourses on spatial order are framing social work (Kessl/Reutlinger 2007, 17):

· The discourse on Globalisation: Local spaces become more and more influenced by global interdependences of trade, culture and migration that reach beyond the former national and local frameworks.

· The discourse on Territorialisation: National states and welfare systems loose their relevance and influence for integration and social security. On this background, local spaces and neighbourhoods (Nahräume) are becoming more important as sources for inclusion, participation, social capital and private engagement. As a result, support programs for social cohesion in poorer and problematic neighbourhoods are gaining more attraction and funding.

· The discourse on Segregation: Processes of social stratification lead to spatial segregation of different status and income groups. Most cities and regions struggle with growing spatial inequalities that are also related to the chances of participation and development of their residents.

· The discourse on Responsibilisation: In societies with growing inequality, anxieties about criminality and disintegration are growing. Local communities, social networks and responsible neighbourhoods are regarded as alternative sources for more safety. Here, local communities are made responsible for more security and crime prevention.

Social work is mutually connected to these four discourses; the public debate influences the role and possibilities of social work. And social work again can reflect these conditions and find positions in response to them. Under the leading idea “from case to space” (Vom Fall zum Feld), spatially oriented approaches in social work are trying to (Kessl/Reutlinger 2007: 41):

· establish and support social networks, local neighborhoods and associations that activate resources and social capital from social networks

· foster more effective forms of cooperation and integration between different public and private services

· realize more collaboration and participation amongst citizens to reach effective forms of help, support and prevention.

For a professionally and ethically reflected social work, the following working principles (Arbeitsprinzipien) should be followed.

2.1 Reflexive-spatial thinking

To prevent a functionalisation of citizens and social workers within spatial discourses, Kessl and Reutlinger (2007, 29) stress the need for reflexive-spatial thinking (reflexiv-räumliche Haltung). Social workers need to reflect about power and dominance in social spaces: Around which interests is the development of a social space oriented? Do these orientations meet the interests and needs of the involved citizens? And do the involved interests enable the social worker to work according to the professional mandate? Here it seems especially important to reflect upon differences of ethic background, class, gender, sexual orientation, age etc. (Deinet 2009, 57).

Instead of establishing and supporting barriers, the general focus of the reflexive-spatial approach should be the creation of new possibilities for citizens (Kessl/Reutlinger 2007, 29). Spatially reflective social workers should identify barriers of social development and support the creation of new possibilities (Deinet 2009, 54). In this sense, social work is always a political profession (Kessl/Reutlinger 2007, 29).

In debates about spaces, two dangers for shortcoming interpretations need to be avoided (Kessl/Reutlinger 2007, 47):

· Symbolic presentations (Symbolische Inszenierungen): To receive more public funding for development processes, certain spatial areas often are described in a negative way, e.g. as “poor”, “neglected” or “dangerous” neighbourhoods. These descriptions are very ambivalent, though. As they can lead to a stigmatisation of whole areas, they might create new problems and prejudices.

· Homogenisations (Homogenisierungen): In descriptions of spaces often the attributes of only a few inhabitants are projected on whole populations and neighbourhoods. Such generalisations should be avoided; it is necessary to differentiate, which attributes apply to which areas or groups.

To avoid misleading judgements, social workers need to reflect on conditions and contexts of the space as well as on the adequacy of the perceptions about a space.

Practice Focus: Clarification of mandates and missions

Social workers often get mandates to work for the prevention of certain behaviour problems of “risk groups” from “problem areas” and the integration of “difficult” groups into local neighbourhoods. By working with such attributions, social workers are involved in the definition of social problems. They should be reflexive about stigmatising and counterproductive impacts for target groups, communities and the profession and decline mandates that violate the ethical standards of social work.

2.2 “Lifeworld orientation” (Lebensweltorientierung)

Following a hermeneutic approach, the German social pedagogue Hans Thiersch formulated the theoretical concept of a “lifeworld orientation” (Grunwald/Thiersch 2009; Engelke, Borrmann, Spatscheck 2009, 427-443). In the spatial paradigm of social work, especially the works of Ulrich Deinet and Richard Krisch are formulated around this concept. For a social worker, lifeworld orientation means to become able to understand the subjective perspectives of citizens within their regional life worlds in an encompassing and deep way as well as to regard citizens as experts for their life worlds (Deinet 2009, 56). Lifeworld oriented social work needs elaborated and reflected forms of observation to gain a deeper understanding of individuals and life conditions. To reach this aim, social workers should take time for grounded observations and considerations on lifeworlds before developing strategies and forms of intervention. Here, Deinet (2009, 29) stresses the need to understand the different values, perceptions and interpretations as well as to commonly reflect them with the target groups. On this basis, perspectives and aims can be developed with the clients. Processes of development can be limited by social conditions. It therefore is of importance to gain clarity about possibilities and limitations of spatial settings to avoid unrealistic expectations amongst the involved actors (Deinet 2009, 58).

Practice Focus: A deeper understanding about the target groups

Social workers often do not have many direct contacts to the everyday life worlds of young people, poor families and people living in subcultures or in dangerous life conditions. Rather their perspectives are focussed around the views of their institutions or their own personal backgrounds. By following hermeneutic perspectives (for methodology refer to chapter 3) social workers can discover and gain a deeper understanding about the everyday life, the ideas, the needs, the wishes and the resources of their target groups and reflect these dispositions within societal conditions and professional standards. On this basis, social workers can build new perspectives with their clients and involved organisations.

2.3 Perspectives of development and education

The main aim of spatially oriented social work is to establish perspectives and conditions for social development processes (Homfeldt/Reutlinger 2009; Reutlinger/Wigger 2008). To reach these aims, the key idea of spatially oriented social work is to involve citizens in the development of social spaces. With the perspective of acquirement (Aneignung), a spatially oriented social work follows an educational and developmental perspective: Through processes of Bildung, individuals should be enabled to realise and enhance their interests and potentials in the context of social spaces (Deinet/Reutlinger 2004). To enable these processes, the conditions of social spaces need to be shaped to support these aims.

Practice Focus: Spatial concept development

On the basis of a deeper and reflected understanding about target groups, organisations and conditions, social workers can build enabling concepts that help to change conditions in social spaces and neighbourhoods together with clients and different institutions. In this sense, every social worker should try to include approaches of social development in the concepts of his/her organisation and enable the addressees to experience processes of acquirement and personal development.

2.4 Research orientation

Following the idea of the social worker as a good observer, Deinet (2009, 48) stresses the need to establish a researcher’s perspective in spatial contexts. Only with a clear and reflected interest for the individuals and their situations, it is possible to gain grounded information and insights about social spaces and individual perceptions. Generally, the “socio-spatial view” (Sozialräumlicher Blick) should find a good combination between perspectives of research and practice (Deinet 2009, 59).

Practice Focus: Reflections on outcomes and conditions

On the basis of lifeworld oriented analyses and spatially reflected concepts, it is also possible to formulate targets for social work interventions and then to reflect on expected and actual outcomes through specially designed research settings. Here it seems to be crucial to define expected outcomes from the perspectives and interests from all included actors (clients, professionals and public) and not just in shortcoming definitions of assimilation, prevention of workfare policy programs. Practitioners can become researchers and be involved in evaluations, outcome measurements and research based concept and theory development without being dominated by other professions.

3 Methodology – How to analyze social spaces?

Social space analyses can be regarded as a form of practice research that can be carried out by social work practitioners or by practitioners and researchers together (Deinet 2009, 59). The analysis of social spaces needs to regard the dialectics of space and (social) development (Reutlinger 2009, 19). The focus of social space analyses should be on developmental perspectives and potentials within social spaces. Therefore, it seems to be necessary to find out more about different concepts of development of the actors (inhabitants, public institutions and professionals, politicians, interest groups, entrepreneurs, etc.) in a social space as well as social conditions and structures. Here, all contradictions and tensions could here be interesting as well as areas of common interest or consensus. As reflexive project, social space analyses need to be sensitive to power and should reflect on what is arranged in the space, who designs the order of the space, and how spaces are emerging through these arrangements.

The focus of social space analyses lies on relational connections and tries to identify spatial differentiations and to look for enabling perspectives for the participating persons and groups (Reutlinger 2009, 20). To get a full perspective, social space analyses can be based on a mixed design of quantitative and qualitative research methods (Riege/Schubert 2005). In this text, the focus of the following spatial research methods will be set on qualitative research approaches. Beyond that, a variety of quantitative approaches to spatial research can be found (Spatscheck/Wolf-Ostermann 2009, 6). For advanced quantitative researchers, a bundle of more complex statistical techniques like analyses of (co-)variance, factorial analyses and cluster analyses is available up to the point of statistical tools for (exploratory) spatial data analyses[2] (Cressie 1993; Goodchild/Janelle 2004; Unwin 1996).

To identify the more subjective and local impressions and the inhabitant’s life world (Lebenswelt), Ulrich Deinet und Richard Krisch developed special qualitative research methods for social space analyses (Deinet 2002, 291/292; Deinet 2009, 65-86; Krisch 2009, 97-109; for qualitative data analyses Denzin/Lincoln 1998 or Flick 2005). Deinet and Krisch have formulated the following methods:

· Structured town walks (Stadtteilbegehungen): This special type of observation is aimed to find out more about a social space through a collection of impressions and perceptions that are gained in direct field experience (Deinet 2009, 66; Krisch 2009, 97). Rather than looking for contact with inhabitants, the researchers look for atmospheric aspects of social interaction in spaces. This method can be refined to “structured town walks” through the definition of fixed routes, and the use of field manuals that enable a higher density of observations. A special form are “town walks with inhabitants” to experience their impressions (Deinet 2009, 68; Krisch 2009, 88). To reach an encompassing picture, it is important to discover a space with different groups and learn from different experiences.

· Qualitative interviews with “key persons” (Befragung von Schlüsselpersonen): This method tries to grasp the views of “interesting” people about their social spaces (Deinet 2009, 70; Krisch 2009, 97). Key persons have to be identified in the local context. Relevant persons could be local shopkeepers, social workers, police men, teachers, health care staff, older inhabitants, etc. that have special and deeper impressions about the space. The interviews should last about 1 or 2 hours and be conducted as narrative interviews. To give the interviews more structure, it is helpful to use an open questionnaire. This method is especially useful to gain deeper understanding when other methods have been applied before.

· Needle method (Nadelmethode): This activating method gives a visualisation of places that are frequented by inhabitants and can be used to show the meaning of certain places (Deinet 2009, 72; Krisch 2009, 97). Inhabitants are asked to pin needles on a map with a higher resolution. They are encouraged to use certain colours for certain meanings. The colours can be coded with criteria like age, gender, “good” or “bad” places, places that are often or never frequented, etc. The results can then be presented, compared, debated and assessed in different groups. An interesting capability of this method are the potentials of visualisation and the direct activation of people that can be involved when passing by. To be easily transported, the needle-maps can be pinned on small boards of Styrofoam. Topographic software solutions like Google Maps or Google Earth and mobile devices with GPS-connection offer new possibilities for this method.

· Peer group grids (Cliquenraster): This method is used to gain descriptions of youth cultures and peer groups in a certain region (Deinet 2009, 79; Krisch 2009, 117). With structured questions, young people are asked about the peer groups they know in a certain area. In the basic mode, the main categories are the name of the peer group, the number and age of the members, their outfit, their preferred music, the behaviour, their preferred places and possible conflicts around the group. Beyond these, all other categories of interest could be applied. After the collection of the data the results can be discussed with young people and local experts. The aim of this method is to gain a realistic overview about different peer groups in a certain area, their connections and the interests of these groups. Based on such assessments, especially youth clubs, youth services and schools can develop improved forms for activities to include the different peer groups. For young people it is often very attractive to be asked as “experts” about youth cultures and scenes in their area. Therefore, this method can lead to higher grades of participation. It would also be interesting to carry out peer group grids on groups of adults and their different life milieus.

· Subjective maps (Subjektive Landkarten): Inhabitants are encouraged to draw personal maps of their daily space of living (Deinet 2009, 75; Krisch 2009). These maps can be designed in open forms and drawers should be asked to show personal thoughts, meanings and perceptions about the space in the pictures. This method is a simplified form of narrative maps, and is used to show and share subjective life worlds. The maps show the outreach in the space, the most important contents and the subjective assessment of meanings, sizes and distances. With additional questions, the researcher can find out more about the subjective experiences. Here, the map can be used as a reference for open interviews with inhabitants. This method can also be applied in groups that are not too big and offer an atmosphere of mutual trust.

· Autophotography (Autofotografie): Inhabitants are asked to choose local places, to take photos with digital or mobile cameras of these places and to finally present, comment and interpret the pictures together with other involved persons (Deinet 2009, 78; Krisch 2009, 115). The choice of the places should follow certain thematic aspects like “everyday places”, “places of special interest”, “ugly or beautiful places”, etc. The pictures show the different individual perspectives on social spaces and allow debates about the design and the condition of spaces, support participation and debates about certain topics like places for certain groups, safety, infrastructure, etc. For good results, the group situations should not be too open and the clear aim of the method should be the common presentation and discussion of the pictures. To reach a stronger motivation, a final presentation for a larger audience can be planned.

· Time budgets (Zeitbudgets): Inhabitants are asked to draw a chart of their daily activities in a protected environment (Deinet 2009, 78; Krisch 2009, 134). Time budgets can especially show the proportions of planned and unplanned activities and give interesting impressions about the different activities. For the spatial perspective, activities of leisure and public life can be connected to time-space-diagrams. Time budgets can be of special interest for the providers of social and public infrastructure. Opening times and programs for different groups can be created more effectively when they are aligned with the habits of the potential users and participants. The data analysis for this method can easily become very voluminous, but this method is highly effective as a participatory form for target group analyses.

· Interviews about institutions (Institutionenbefragung): With the help of structured questionnaires, inhabitants are asked to give their assessment of their local public and social infrastructures like youth clubs, schools, day centres, social services, health institutions, etc. (Deinet 2009, 84; Krisch 2009, 149). With this method, researchers can find out, which institutions are known in which context, and which strengths and weaknesses these institutions show in the spatial context. This method can be supplemented with staff interviews on these institutions. Finally it would be interesting to compare the different perspectives.

In general, social space analyses should regard inhabitants as experts of their life world that deserve to keep their unique dignity and interests. Therefore, the methods for social space analyses should be carried out according to the ethical aspects of research. This means to protect personal data through anonymisation and to inform all participants about the intentions and the participating interests of the research project and to point out the fact that participation is voluntary. In this sense, it is also important to keep aspects of power in mind and to ask who will benefit from the results and whether the researcher intends to have this benefit. Also, it is important to keep participant’s expectations realistic; not every interview or participation process can lead to direct impacts and the fulfilment of all wishes of interviewed persons. In any case researchers undertaking social space analyses should have a profound knowledge of (quantitative and qualitative) research methods and their strengths but also their limitations.

4 Socio-spatial approaches to social work – an outlook

Socio-spatial approaches can be applied in the context of a broader social development perspective that follows to shape living conditions and structures as well as the improvement of the inclusion and participation of local residents (Homfeldt/Reutlinger 2009). In this sense, socio-spatial approaches should search for solidarity and try to enhance local networks (Reutlinger 2009, 29). Spatial approaches in social work could aim to revitalise public spaces and look for an improved collaboration of social work, social policy and youth policy (Deinet 2002, 294).

Under the term of “social space work” (Sozialraumarbeit) Reutlinger and Wigger (2008) try to bring three areas of public activities together:

· Individual perspectives of citizens and residents

· Administrative perspectives of social services, public administration, schools and health care organisations

· Town planners and architectural perspectives around planning and development of buildings and public infrastructure.

The encompassing approach of social space work seems to be very promising, albeit the integration of such different fields of practice would certainly bring many challenges for the involved institutions. For a perspective of common spatial development, there seems to be one common denominator: The “socio-spatial view” as a basis for collaboration of different actors for the development of positive local living conditions and the design of effective social, educational and healthcare services (Deinet 2002, 295).

References

Baacke, D. (1984): Die 6-12jährigen. Weinheim.

Bachmann-Medick, D. (2006): Cultural Turns. Neuorientierungen in den Kulturwissenschaften. Reinbek.

Böhnisch, L. / Münchmeier, R. (1990): Pädagogik des Jugendraums. Zur Begründung und Praxis einer sozialräumlichen Jugendpädagogik. Weinheim.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979): The Ecology of Human Development. Cambridge.

Budde, W. / Früchtel, F./ Hinte, W. (eds.) (2006): Sozialraumorientierung. Wege zu einer veränderten Praxis. Wiesbaden.

Castells, M. (2001): Das Informationszeitalter I. Die Netzwerkgesellschaft. Opladen.

Cressie, N. (1993): Spatial Statistics. New York.

Deinet, U. (2002): Der >>sozialräumliche Blick<< der Jugendarbeit – ein Beitrag zur Sozialraumdebatte. In: neue praxis (32), 285-296.

Deinet, U. (2006): Aneignung und Raum - sozialräumliche Orientierungen von Kindern und Jugendlichen. In: Deinet/Gilles/Knopp (2006), 44-63.

Deinet, U. (2007): Sozialräumliche Konzeptentwicklung und Kooperation im Stadtteil. In: Sturzenhecker/Deinet (2007), 111-137.

Deinet, U. (ed.) 2009: Methodenbuch Sozialraum. Wiesbaden.

Deinet, U. / Gilles, C. / Knopp, R. (eds.) (2006): Neue Perspektiven in der Sozialraumorientierung. Dimensionen – Planung – Gestaltung. Berlin.

Deinet, U. / Krisch, R. (2006): Der sozialräumliche Blick der Jugendarbeit. Methoden und Bausteine zur Konzeptentwicklung und Qualifizierung. 2nd edition, Wiesbaden.

Deinet, U. / Reutlinger, C. (eds.) (2004): 'Aneignung' als Bildungskonzept der Sozialpädagogik. Beiträge zur Pädagogik des Kindes- und Jugendalters in Zeiten entgrenzter Lernorte. Wiesbaden.

Denzin, N. / Lincoln, Y (1998): Collecting and Interpreting Qualitative Materials. Thousand Oaks.

Dünne, J. / Günzel, S. (eds.) (2006): Raumtheorie. Grundlagentexte aus Philosophie und Kulturwissenschaften. Frankfurt a.M.

Engelke, E. / Borrmann, S./ Spatscheck, C. (2009): Theorien der Sozialen Arbeit. Eine Einführung. 5th edition, Freiburg i. Br.

Flick, U (2005): Qualitative Sozialforschung. Eine Einführung. 3rd edition, Reinbek.

Früchtel, F. / Budde, W. / Cyprian, G. (2007): Sozialer Raum und Soziale Arbeit. Fieldbook. Wiesbaden.

Früchtel, F. / Cyprian, G. / Budde, W. (2007): Sozialer Raum und Soziale Arbeit. Textbook. Wiesbaden.

Goodchild M.F. / Janelle, D.G. (eds.) (2004): Spatially Integrated Social Science. Oxford.

Grundmann, M. / Kunze, I. (2008): Systematische Sozialraumforschung: Urie Bronfenbrenners Ökologie der menschlichen Entwicklung und die Modellierung mikrosozialer Raumgestaltung. In: Kessl/Reutlinger (2008), 172-188.

Grunwald, K. / Thiersch, H. (2009): The Concept of the 'Lifeworld Orientation' for Social Work and Social Care'. In: Journal of Social Work Practice (23), 131-146.

Hinte, W. (2006): Geschichte, Quellen und Prinzipien des Fachkonzepts „Sozialraumorientierung“. In: Budde/Früchtel/Hinte (2006), 7-24.

Hinte, W. / Lüttringhaus, M. / Oelschlägel, D. (2007): Grundlagen und Standards der Gemeinwesenarbeit. München, 2nd edition.

Hamburger, F. (2007): Einführung in die Sozialpädagogik. Stuttgart, 2nd edition.

Homfeldt, H. G. / Reutlinger, C. (2009): Soziale Arbeit und Soziale Entwicklung. Baltmannsweiler.

Kessl, F. / Reutlinger, C. / Maurer, S. / Frey, O. (eds.) (2005): Handbuch Sozialraum. Wiesbaden.

Kessl, F. / Reutlinger, C. (2007): Sozialraum. Eine Einführung. Wiesbaden.

Kessl, F. / Reutlinger, C. (eds.) (2008): Schlüsselwerke der Sozialraumforschung. Traditionslinien in Text und Kontexten. Wiesbaden.

Kleve, H. (2008): Sozialraumorientierung - eine neue Kapitalismuskritik in der Sozialen Arbeit? In: Spatscheck et al. (2008), 76-93.

Krisch, R. (2009): Sozialräumliche Methodik der Jugendarbeit. Aktivierende Zugänge und praxisleitende Verfahren. Weinheim.

Löw, M. (2001): Raumsoziologie. Frankfurt a.M.

Löw, M. / Steets, S. / Stoetzer, S. 2008: Einführung in die Stadt- und Raumsoziologie. 2nd edition, Opladen.

Meinlschmidt, G. (ed.) (2009) Sozialstrukturatlas Berlin 2008 – Ein Instrument der quantitativen, interregionalen und intertemporalen Sozialraumanalyse und -planung – Spezialbericht 2009-1. Berlin.

Otto, H-U. / Scherr, A. / Ziegler, H. (2010): Wieviel und welche Normativität benötigt die Soziale Arbeit? Befähigungsgerechtigkeit als Maßstab sozialarbeiterischer Kritik. In: neue praxis (40), 137-163.

Preuss-Lausitz, U. / Deutsche Gesellschaft für Soziologie. Arbeitsgruppe Wandel der Sozialisationsbedingungen seit dem Zweiten Weltkrieg. (1983): Kriegskinder, Konsumkinder, Krisenkinder. Berlin.

Riege, M. / Schubert, H. (eds.) (2005): Sozialraumanalyse. Grundlagen, Methoden, Praxis. 2nd edition, Wiesbaden.

Reutlinger, C. (2009): Raumdeutungen. Rekonstruktion de Sozialraums „Schule“ und mitagierende Erforschung „unsichtbarer Bewältigungskarten“ als methodische Felder von Sozialraumforschung. In: Deinet (2009), 17-32.

Reutlinger, C. / Wigger, A. (2008): Von der Sozialraumorientierung zur Sozialraumarbeit – eine Entwicklungsperspektive für die Sozialpädagogik. In: Zeitschrift für Sozialpädagogik (6) 340-372.

Sandermann, P. / Urban, U. (2007): Zur >Paradoxie< der sozialpädagogischen Diskussion um Sozialraumorientierung in der Jugendhilfe. In: neue praxis (37), 42-57.

Spatscheck, C. (2009): Methoden der Sozialraum- und Lebensweltanalyse im Kontext der Theorie- und Methodendiskussion der Sozialen Arbeit. In: Deinet (2009), 33-44.

Spatscheck, C. / Arnegger, M. / Kraus, S. / Mattner, A. / Schneider, B. (eds.) (2008): Soziale Arbeit und Ökonomisierung. Analysen und Handlungsstrategien. Berlin.

Spatscheck, C. / Wolf-Ostermann, K. (2009): Social Space Analyses and the Socio-Spatial Paradigm in Social Work. Working Paper 2009-1, School of Social Work, Lund University. http://www.soch.lu.se/images/Socialhogskolan/WP2009_1.pdf, Rev. 2010.11.21

Sturzenhecker, B. / Deinet, U. (eds.) (2007): Konzeptentwicklung in der Kinder- und Jugendarbeit. Reflexionen und Arbeitshilfen für die Praxis. Weinheim.

Unwin, A. R. (1996): Exploratory spatial analysis and local statistics. Computational Statistics (11), 387-400.

Zeiher, H. (1983): „Die vielen Räume der Kinder. Zum Wandel räumlicher Lebensbedingungen seit 1945“. In: Preuss-Lausitz (1983).

Author´s

Address:

Prof. Dr. Christian Spatscheck

Hochschule Bremen, University of Applied Sciences

Faculty of Social Sciences

Neustadtswall 30

28199 Bremen

Germany

Tel.: ++49 (0)421 5905-2762

Fax: ++49 (0)421 5905-2753

Email: christian.spatscheck@hs-bremen.de

www.christian-spatscheck.de