Regional Policies and Individual Capabilities: Drawing Lessons from two Experimental Programs Fighting Early School Leaving in France

Thierry Berthet and Véronique Simon, Centre Emile Durkheim-Céreq, Université de Bordeaux

Dropouts are newcomers on the French political agenda. Until the beginning of the years 2000, early school leaving was not a matter of concern for the French politicians and only a few academic work had been done on that topic (Bernard, 2011 ; Glasman and Oeuvrard, 2011). It started to change after the 2005 urban riots. Usually, one would think a problem tends to become a matter of public policy when gaining significance in society, and weighting increasingly on social and political structures. Nonetheless, there is no denial that ever since their numbers have significantly decreased in France[1], school dropouts have never been more mentioned[2]. If on a strictly numerical basis, there are less school dropouts, one should look elsewhere for the reasons why this issue became a public problem.

A first set of justification can be found in the existence of educational norms, which make the continuing elevation of qualification levels one of the intangible objectives of education policies. However, short of considering that these norms proceed from a purely humanist and philosophical aspiration, one must resort to a second, “upstream” order of justification. This second justification is related to the difficulties encountered by the dropouts to get access to the labour market.

The issue at stake is not related to a shortage in low-skilled jobs. After a significant decrease during the 80s, low-skilled jobs bounced back in the mid 90s: in 2001, their share had returned to their 1982 levels, mostly due to a rise in the service industry (Rose, 2009). Hence the issue does not result from a shortage of unqualified jobs but in a labour market increasingly adverse to unqualified young workers. In other words, dropout has become a public problem mainly because access and stability in employment is more complicated and difficult for early school leavers, in a context of massive unemployment where young people in general and low-skilled youngster in particular constitute a very vulnerable category to the selective mechanisms of the labor market (Céreq, 2012).

The inscription of the dropout issue on the agenda occurred in a complex political landscape where different type of actors coexist:

· Government departments (ministries of education, labour and employment, and youth, as well as their sub national representatives)

· Local governments (conseils régionaux, généraux et municipaux, i.e. regional, sub-regional and city councils), whose legitimacy to intervene in this field remain uncertain.

· Local structures and networks: (missions locales, maisons de l’emploi, centres d’information et d’orientation, centres interinstitutionnels de bilan de compétences[3]) in charge of implementing the public policies.

Such actors coexist on several territorial levels of government and cohabitate within intricate hierarchical and organisational relationships clearly stating the relevance of interrogating their governance (Lascoumes and Le Galès, 2007). At the systemic, or national level, numerous measures and instruments loosely coordinated and quickly outdated, decommissioned or scarcely financed, can be identified (Bernard, 2011 ; Blaya, 2010 ; Bonnery, 2004 ; Glasman and Douat, 2011). At the local level, one can observe a profusion of experimentations, individual or collective initiatives, all characterised by a strong awareness of the need for increased cooperation in public action. However, is the local political scale always the adequate one? Indeed, distortion effects push for concentrating investment on urban areas, whereas early school leavers are as numerous, if not more, in rural areas, but the absolute numbers often outweigh the ratios of dropout to the whole school population.

In any case, this short overview strongly raises the question of coordination and coherence in public policies designed to prevent dropout. Social experimentation has recently been promoted as a tool for establishing links between different levels of government, while stimulating innovation. Social experimentations have come to constitute a government strategy aiming at sustaining local programs for educational completion, lead by the “Fond d’Expérimentation pour la Jeunesse” (F.E.J[4]). This is the subject of the present case study, regarding two regional experimentations designed to fight school dropout. The presentation of our results is organised in two steps. In a first section, we will present the two regional programs, our methodology and some overall results. The second section will be dedicated to their analysis in terms of capabilities. The capability framework will provide not only an interest to the resources provided but will also show how individual conversion factors are included or not in the design of regional public policies. This bottom up analysis will allow us to understand how individual capabilities are strengthened or inhibited by public action towards early school leavers.

1 Studying two regional programs: methodological insights and overall results

Our main objective here is to explore the relationship between the institutional capacity of local policies stakeholders and the actual possibilities to enhance individual capabilities. To conduct this analysis, we have worked on two different regional situations as one case study. This two-fold study will allow us to show the differences of political capacity and coordination building and the impact of such differences in terms of services delivered to beneficiaries.

1.1 Case study’s objectives and methodology

We aim at underlining the regional disparities of these policies by studying a region (Rhône-Alpes) where the regional council (conseil régional) has decided to launch a territorial policy to prevent and reduce school dropout on the basis of a strong partnership with the ministry of education and another region (Aquitaine). Such policies launched at a regional scale are generally carried out with little cooperation between these two policy levels. Yet a series of contextual evolutions has created a policy window for their action:

· Preventing dropout has recently been put on the agenda and this policy has hardly stabilised.

· Relying on its competencies in the field of professional training the regional council has progressively invested the issues of guidance and securing career paths. It has therefore gained significant institutional resources in organising dropout prevention.

· The ministry of education’s operational and financial resources has been strongly reduced.

· Regional councils are (except for one) controlled by members of parties opposite to the national government.

We have then chosen to focus our observations on two social experimentations, respectively launched by two regional councils in the Rhône-Alpes and Aquitaine (NUTS 2). Both experimentations share common characteristics: they are experimental programs carried out by the regional council, resting on a partnership-based management, and supporting local initiatives. These two programs are co-financed by the F.E.J and are respectively untitled: regional plan for fighting dropout (Rhône-Alpes) and regional plan for school perseverance (Aquitaine). Two distinct modes of action appear in these two plans: by supporting existing local networks that are fighting dropout through an improved monitoring of dropouts in Aquitaine and by providing the schools with additional funds as a means to prevent dropout in Rhône-Alpes.

The method used for the case studies is based on documentary analysis and a series of semi-structured interviews. The documentary analysis focuses on policy documents, study reports and review of scientific articles. We have conducted 45 semi-structured interviews during the summer and fall 2011 with 3 categories of actors: regional public authorities; local operators (head teachers, heads of school, teachers, guidance counselors); and pupils. Concerning this last category (pupils), we have conducted these interviews in three modes (individual face to face, small groups of 3-5 pupils, larger class group >10) on the basis of an interview grid focused on capability for voice/education/employment.

Although our methodology remained unchanged at the regional level, we adapted our interviews to the local context and the aims of the program. In Aquitaine, we have conducted our interviews with the local network’s organisations. They introduced us to a series of early school leavers’ groups and individuals. In Rhône-Alpes, the fieldwork was conducted vis-a-vis the teaching institutions and pupils included in the action plan implemented in this school. Our fieldwork in Rhône-Alpes focused on 5 teaching institutions in both the districts of Lyon and Grenoble: two vocational upper secondary schools from the public sector, one public agricultural college, one private agricultural college (maison familiale et rurale) and finally one upper secondary school specialised in bringing drop outs back to school (Collège et Lycée Egalitaire Pour Tous – CLEPT). In each of these institutions, we met with the administrative staff, the teaching teams, the dropout monitoring teams (when existing) and several group of pupils.

1.2 Presentation of the regional programs

As mentioned above, our fieldwork is also two-folded as we have chosen to study two regional action plans against school dropout (in Rhône-Alpes and Aquitaine). The first one focuses on supporting existing local networks of actors, the second funds experimental actions conducted inside the teaching institutions.

1.2.1 Rhône-Alpes

The regional plan in Rhône-Alpes consists in financing innovation within schools and was launched in 2008. It results from an agreement between the regional council, the ministry of education (more precisely two of its regional sub-divisions called rectorats), the regional Directorate for Alimentation, Agriculture and Forests (DRAAF) and the regional network of the “missions locales” (i.e. local interdepartmental structures dedicated to vulnerable young people). The public problem this plan wished to tackle was based on the finding of a significant number of early school leavers with no qualifications. Therefore, the regional council decided to prevent early school dropout by giving extra funds to schools in order to support pupils. Hence a call for proposals was launched and its objectives were “ to improve and develop prevention of school dropout in order to reduce the rates of early leave in professional training schemes”. The applying schools were to submit “an innovative approach for identifying and providing extra help for struggling pupils” and were asked to submit proposals based on the following approaches:

· Identification, prevention and research for adequate solutions

· Tutoring

· Individualised follow-up process for pupils (when enrolling and beyond)

· Providing re-incentives and remobilisation to pupils: allocating time for personal development through socialisation, self-appreciation, skills’ enhancement workshops

· In-depth counseling on guidance and academic choices (Rhône Alpes regional plan).

This plan was directed to both public and private secondary schools, vocational and agricultural. The call for proposals was open for three years (2008-2011) and had a global budget of 1.5 million Euros. Out of the 125 submissions, 91 projects were selected including 80 exclusively submitted by a school.

The services of the regional council have produced a general assessment of the plan and several significant observations can be made on the basis of the record:

· The main axes of the projects were: training for teachers, small group remobilisation workshops, individual counseling for at-risk pupils, tutoring, as well as personal and inter-personal competencies development;

· 80% of the requests for funding concerned overtime pay;

· Projects were mostly limited to one single school, and partnerships rarely extended to the information and guidance services;

· Projects often referred to families and pupil’s involvement, but only giving them some general information about the project generally carries this out.

Regarding the regional plan and projects’ management, one should first emphasize that the program raised interest among schools, since almost half of the 230 eligible schools in the area took positions and submitted applications. In a context of decreasing national public funding for secondary education, the subsidies distributed by the regional council helped offset the lack of funding from national policies. “I think that globally, for the school involved, it has given them some air to breathe and has widened horizons a little” (Regional council, upper secondary school staff).

The founding partnership for the program, formalised in an agreement, has brought together the regional council, the regional authorities for the Education Department, the Agriculture department and the network of “missions locales”. According to the actors interviewed, the regional partnership has been working to their satisfaction, provided two reservations:

Although they are key in the implementation of these policies, the missions locales’ involvement has been limited, due to a program design mainly focused on schools as evidenced by both the regional plan and the projects submitted by the public, non-vocational secondary schools. “When looking at the projects, what are you told? I will be very, very caricatural : if the pupil drops out, your job is to lead him to the” mission locale”. But it is our usual activity to take responsibility for these young people. What we would have wished for is the development, for instance, of direct permanent presence within the schools. Well, it was obvious that this was not an option” (Rhône Alpes, mission locale regional network).

The monitoring of the regional plan entrusted to the “Pôle Rhône-Alpes de l’Orientation” (i.e. Guidance pole for Rhône-Alpes, or PRAO) included a mission of precise inventory for dropout in the region. However, the regional authorities of the Education Department (rectorat) have not shared the necessary extractions from their databases to make such calculations. This situation has created uneasy relationships between the regional council and the two “rectorats”. “Then, there was a big fear to reveal things threatening an institution that is already quite weakened. The more they fear, the more they lock up, and the more complex it gets, the more aggressive interpersonal relationships become” (Regional council, upper secondary school staff). As a result, the PRAO had to resort to other extrapolated statistical sources to perform its task.

Regarding the systemic effects that have been observed in the schools, two elements can be pointed out:

· A mobilisation effect of the teachers and administrative staff: “ I think in terms of effect, the very first thing is that in participating in the plan, the schools said it helped us to tackle the issue. That is to say that as soon as they drafted a proposal, (…), it has had an internal mobilisation effect.” (Rectorat de Lyon, guidance and counseling division)

· An awareness effect for teachers involved de facto in an internal program aiming at fighting dropout, while the issue tends to be increasingly externalised towards non-academic operators (psycho-motor therapists, dropout advisors, speech-language pathologist, etc…). “It did bring too, thanks to the means and the funding, I think it has an effect of overtime pay and so on, it allowed each Head of School to have the means to foster mobilisation, especially with the teachers. That is the second effect”. (Rectorat de Lyon, guidance and counseling division).

In the end – according to the regional stakeholders and that was confirmed by our own interviews with teachers and head teachers – the regional plan for fighting school dropout will have instigated a project dynamic and initiated innovation.

1.2.2 Aquitaine

The project carried out by the regional council in Aquitaine is untitled “Networks for school perseverance”. The wording “school perseverance” to designate dropout is quite unusual in France, yet frequently used in Quebec. This can be explained by the beginning of the project in Aquitaine that is related to a fact-finding mission conducted in Quebec in 2006. When in 2008, the regional council considered getting involved in preventing school dropout, three territories where pre-existed a cooperative dynamic between local stakeholders were identified (Marmande, Blaye and Hauts de Garonne). Based on such findings, a second fact-finding study in Quebec was commissioned with local stakeholders in the aim of stimulating the networks they were already involved in or were about to create. “So we identified those three territories and offered them the following deal: we will organize a mission to Quebec (and I will provide you with an account of this mission in 2008), the deal is not to copy-paste what is done in Quebec but we can draw inspiration from it, hear principles out, see work approaches and postures, and the deal is to come back in Aquitaine and with your operators, your projects in common, to try to put those methods into practice. So you will come together on a set of objectives defined in a charter, there are no directives, no framing, it is just a way to approach things, and then we will try and see to what extent you can work together” (Regional council, drop out mission). This is how the axis for regional policy has been defined, consisting in stimulating and providing tools for existing networks of operators.

The network was launched in 2008 and was also co-financed by the FEJ during the 2008-2011 period. The objectives of this experimental approach consist in:

· “Supporting and encouraging partnership and network-setting of distinct institutions, structures and organisations that are locally involved with dropout, so as to reinforce their cooperation for a better support provided to young people.

· Accompanying the three local and experimental networks for perseverance and success of young people in their areas, in their action for identification and monitoring of young dropouts, potential or actual, facing difficulties in academics and / or professional insertion.”

The main actions set up by the regional council in this plan are as follows:

· “Recruiting an agent specifically dedicated to the management of regional policy for perseverance within the Education division

· Validating the recruitment of three coordinators from the experimental networks” (Aquitaine regional program)

In Aquitaine, the project was implemented in a global context of tension between the regional council and the rectorat. “And the rectorat always said that the Region was creating a program adverse to ours, they are outside of their competences, etc. (…) Of course the tension was obvious with the actors from the ministry of education who did not regard kindly inviting at the table, on issues relevant only to them, people they did not recognise the relevance or expertise” (Regional council, Education division). It is indeed quite likely that choosing to invest on the axis of network-building, rather than intervening directly on school policiy like in Rhône-Alpes, is due to this particularly tensed relationship between regional council and rectorat of Aquitaine on the dropout issue in 2008.

Putting the application together has at first been slightly chaotic, yet implementation began in 2009. Over the three targeted areas, only two got involved in the project as confirmed by the official in charge of the program: “ and for the “Hauts de Garonne” nothing happened”.

Following requests from the local actors, the main axis for action consisted in recruiting two coordinators in charge of animation of the local networks and thus being able to dispense operational staff involved in preventing dropout of all bureaucratic and managerial tasks. Soon though, a second objective came alongside: developing an intranet program at the local network scale in order to identify and monitor in real time young dropouts. This program, named SAFIRE (Solution d’Accompagnement à la Formation, l’Insertion et la Réussite Educative i.e. Support for Formation, Insertion and Academic Success Solution), has been developed on the territory of Blaye and implemented on both the Blaye and Marmande area. This development task, carried out by the coordinators recruited for the project, is very much appreciated by local operators: “This is enormous work, it took him time, he went to all the schools so as to appoint referring operators in charge of pupils’ perseverance, he trained academic staff to use Safire. Thus it is something who had a very positive impact, because alerts have been doubled” (Mission locale, Blaye).

The regional program’s twofold axis, coordination of local operators and implementation of a monitoring device, collided with a national policy launched in February 2011. Indeed, a circular from the ministry of education introduced two new devices: local platforms for monitoring and support, and the SIEI (Interdepartmental System for Exchange of Information). Those two measures, that local officials from state services have to implement, brutally collided with the local experimentations realised in Aquitaine[5]. “We have been hit by this and de facto, we cannot keep our programs alive with the platforms since our operators are fully involved in the operationalisation of such state policy, and are compelled to implement it” (Regional council, Education division).

In the end, the two staff members coordinating the networks will not have their contract renewed beyond the experimentation calendar (December 2011), and the future of the IT program SAFIRE is at the very least uncertain, since operators in state services have been advised to give priority to the national SIEI program.

1.3 Common findings

Regarding political results, given that the two experimentations are coming to an end, here are our general findings about these two regional programs:

· In terms of institutionalisation: no extension or continuation of the projects since they have been considered at the end of the experimentation

· In terms of partnership: dropout appears as an issue strongly marked by political tensions between regional council and “rectorat”, especially regarding data transmission on dropout and project management.

· In terms of project management: the collision of local and national agendas. Governmental initiatives (SIEI and local platforms) launched after the beginning of experimentations and particularly in respect to identifying drop outs, have impacted and sometimes destroyed local experimentations (Aquitaine)

· In terms of relation to the beneficiaries: Young people and their families have usually not been given a lot of time for voicing their concerns, even when the program was specifically targeting the schools.

The global observation one can provide for both national and local levels is one of limited actions in time and space, strongly undermining public action’s continuity yet a constitutional principle in France.

· For decision-makers: redundant competences overlap and conflicts arise at the unstable margins of decentralisation and national competences.

· For operators: local experimentations are alive but remain sensible to the regional political context.

· More generally, a picture of uncontrolled repetition of very similar programs seems to come together.

2 An analytical view of the three relevant capabilities onto the case study

Even if enhancing the capabilities for voice, education and work is not an explicit aim of both the regional programs studied here, the normative dimension of the capability approach makes it possible to use these three categories as means of analysis and evaluation. Are those programs vectors for reinforcement of capabilities (Sen 2000)? To what extent and how do the resources allocated to school projects allow for an increase/ enhancement in the actor’s actual freedoms, in this particular case pupils (Bonvin and Farvaque, 2008)?

2.1 Analysing the regional programs in terms of capabilities

Despite the fact that our interview grids where designed to shed light on the capability dimensions, we decided to implement a three-step process in order to operationalise the capability approach as an analytical tool for our empirical material. The first exploitation of our interviews focused on identifying in each of them the main aspects related to one of the three capabilities investigated (voice, education and work). On this basis, a second exploration brought to light the transversal characteristics of each of those capabilities. Third, we have then assessed the extent to which these capabilities were effectively enhanced for the pupils involved in these programs, i.e. we assessed the freedom dimension, both in its process-based aspects (democratic participation) and its social justice principles (choice between a plurality of value functioning or adaptive preferences).

2.1.1 Capability for voice

The voice can be a crucial element of some projects. A capacitating project in terms of voice is one that implies, according to us, the active involvement of pupils at all stages of its launching (design, implementation, assessment) but grants them also the freedom not to participate. More generally, a project will be enabling if pupils view its implementation positively. Hence, the later are not compelled to participate in experimental programs. They are invited to get involved and therefore have good information about the program (families nonetheless have less systematic access to information). The plan targets pupils with the more difficulties yet it should not identify them as such and thus preventing for stigmatisation as a reason for non take-up. They are granted easy access to the program (free access) and the organisation takes into account their constraints (timetables, public transportation, living conditions…) and what they appreciate and give value to. Pupils can be a force of proposal, for the choice of a school field-trip, or for the timing and the discipline of tutoring for instance.

Voice can also be absent in some projects. In such cases, pupils have no or very little information about the different aspects of the project or even about its existence, and when they had access to some, it remained unclear. The fact that they actually understood the aim of the project does not seem to have been verified. Pupils for instance think they are getting grades from the tests they are given, and have only a very vague idea of what they could be used for[6]. It was very salient from the interviews with pupils benefiting from this type of projects that what was done bore no value nor had any use to them. The different parts of the project have been conceived without their input and they are forced to participate since they can be excluded from school otherwise. According to them, the only way to express themselves is an institutionalised one, through the “délégués de classe” or pupil representatives. Outside of such representation, they have no voice granted to them.

From the operator's point of view, voice seems to be effective to different extents, and under distinct forms from one school to another. The Maison Familiale et Rurale de Chessy (Family Rural House of Chessy) has created spaces for listening and expression for 3rd years pupils (approx. 14-15 years old), for instance, and instituted discussion groups. Besides, psychological support has been set up for voluntary participants who can choose the place and the topic of those sessions.

The agricultural secondary school of Montravel makes space for capability for voice: free to express their opinions, pupils are involved in field-trips, mentoring and tutoring scheme they can jointly elaborate with the teachers and the administrative staff. In the vocational secondary school Martin Luther King, voice might be less dominant in the operator's mind. The school organises tutoring on a voluntary basis and pupils can pick the topics they wish to study with the school non-teaching staff. In the vocational secondary school Marcel Seguin, the analysis of the interviews conducted with heads of school and teachers matches the one with the pupils but mentions very scarcely the dimension of capability for voice. Outside of the welcoming week when pupils are offered individual meetings and sessions are organised with families, added to the fact that a pupil can refuse individual care, the indicators for voice are largely absent.

The “Collège Lycée Elitaire pour Tous” (CLEPT what loosely stands for the Elite secondary school for all) is an experimental school (Bloch and Gerde, 2004). It offers an alternative educational approach for dropouts (they have an average 18 months of school dropout before getting into the CLEPT). Small groups, tutoring, step-by-step assessments, writing workshops, academic and cultural sessions, initiation to philosophy, are some of the many devices designed to promote “the construction of youngster’s own authority in acts, an on-being acting on its own citizenship and its own learning processes”. We have met students from one basic group (independently from their grades and their level) and some of the teaching staff. The interviews show that developing capability for voice is at the very heart of the promoted educational approach. “The rules of the CLEPT (…) are jointly constructed” (CLEPT, teacher). They imply “working all year long”, can be adjusted depending on the students, “we hear what they have to say” (CLEPT, teacher) and they are given incentives: “they will not get shut down because they said something outside of the question asked, badly formulated, so speech is risk-free” (CLEPT, teacher). Pupils confirm: “Regarding self-expression, first you need to know that already in our timetables we have slots, just like for groups, what we are doing now, where self-expression turns around the table, on news, on internal issues for the CLEPT. We also have a “vie de classe” (class meeting) happening every week. I know some schools where the “vie de classe” is every six months, I exaggerate but really it is very rare. Here again, it is a space where we can really express ourselves. Then we have the tutoring, that is to say the teachers are tutoring us and besides we can express ourselves but it is in a more personal context.” (CLEPT, pupil).

2.1.2 Capability for education

The pupils perceive capability for education mainly as an instrumental way to access a substantial one (capability for work). According to them diplomas matter to get a valuable job. The Baccalauréat (A-level) is envisaged here as a conversion factor, increasing their positive ability to do something worth it. The social norm does indeed makes it crucial to get this degree in order to access the job market more securely.

For the majority of our interviewed youngsters, being successful at school has value. Pupils are receptive to dominant norms in society . In order to guarantee the achievements they desire, i.e. to get “good wages, a family, a job” as stated by the pupils from a vocational upper secondary school, they know that a definite level of education or qualification is compulsory. Beyond such level, their situation would be unacceptable in terms of well-being: “with no education, you have no job, you don't manage (…), your life is a waste” (pupils from a vocational upper secondary school, Lyon). Education is not perceived as an end but as the means to to be more able to choose a way of life. In the hierarchy of choices we submitted them, “completing education” comes for most of them before “getting a job”.

Ideally, a capacitating project would guarantee that pupils obtain a degree they value, which would provide them with opportunities for continuing their education. In reality, a project can develop access to degrees through “individual conversion factors”. The help provided is then academic and psychological. Attention is focused on the individual, in supporting his/her self-esteem, help to study, tutoring in some subjects where he/she encounters the most difficulties, or even mentoring the elaboration of a career aspiration of value for him or her. Yet such projects impact the beneficiary after a series of choices sometimes strongly forced on them. Pupils might have been enrolled[7] in a cursus they did not choose. It is thus virtually impossible to witness any capability development. The regional plan impacts possibilities predetermined by the education system constraints.

In a number of schools under study, even when pupils do say they feel at ease, they can be there “as a last resort” since it was, in some cases, their ”5th choice!” (Pupils from a vocational secondary schools, Lyon). Agricultural education might have been chosen for its alternative pedagogical approach, as a solution to failure to continue education in other schools. In itself, agricultural education is capacitating, since numerous pupils can access to a qualification they would not have as certainly obtained otherwise.

In Aquitaine, the regional plan is targeted on youngsters after they dropout, therefore it does not act inside the teaching institutions. Its aim is to sustain the existing networks of social workers, educators, and guidance counselors. When assessing the degree of capability for voice enjoyed be the youngsters enrolled in the program, it is obvious that their voice was very low during schooling and remains still very low during the dropout period.

Teachers and head teachers do not all mention, at least explicitly, a concern for developing capabilities for education. In its educational project, a school like the vocational upper secondary school Marcel Seguin remains speechless in that respect. However, some schools do put as a central aim of their projects the well-being at school dimension: pupils should “feel well at school” (teacher, Lycée de Montravel), enjoy learning again. They can focus on contents, on meaning or interest for education in itself. Teachers from the vocational school Martin Luther King explain: “As French teachers, we often see that the one who will make it professionally is first someone who can make the language its own: that is to say that he is able to say what he wants, to formulate a need, to understand and thus this disqualification of French in vocational schools reinforces the idea of a second-class subject, it is then much more difficult for us to demonstrate its interest. In the end pupils are quite happy to tell themselves that French is not an important subject”. Besides, for this school, the issue at stake is to provide a type of affirmative action by allocating in priority the classes to new migrants. In other words, the school is looking to promote more conversion factors for those who might be the most impeded to complete their education.

2.1.3 Capability for work

The Rhône-Alpes’ program is carried out within the schools. It is by definition more focused on education than employment. However, all the pupils we have met are already very concerned with their insertion on the labour market. This project could be considered as aiming at guaranteeing a specific functioning: getting a job. But is it always a self-valued functioning? In order to answer this question, let's quote a very typical interview:

Celia

We met Celia on the sidewalk in front of the high school a day of exam. She expresses very accurately the adaptive preferences and the importance of getting a job above all:

The final objective is to find a job?

Of course (silence).

[The silence following the statement reveals heavy constraints, when listening to the next answer:]

So do you know what you want to be?

“Well I enrolled in accounting, I take classes in vocational training for accounting, if I keep it up I think I will end up as an accountant”.

[Ending up in accounting! In colloquial French it does not convey any sense of gratification. Ending happens when there is no more hope. You don't end up a millionaire; you end up homeless. Here lies all the weight of resignation. The words “adaptive preference” do apply here, which the rest of the interview confirms:]

Were you the one to choose?

Basically, no. It was my last resort.

What would you have wanted to do?

Social worker

And it was not accepted?

I have not been accepted in secondary schools -clears her throat- I was not good enough in sciences so well, I applied here, in accounting

[But she stays in the game and complete education because it matters in order to get a job]

Is it important for you to continue your education after secondary school?

Anyways, you’ve got to! (laughs) That's what you need now to get a job.

Is it important to you to get a degree in order to get a job?

Personally I think, employers ask for diplomas anyways so after to get a job you automatically have to get one.

Similarly to the way operators did not seem in their discourses to deliberately develop capabilities or education, all operators do not emphasize the capability for work dimension. Some openly mention capabilities for employment: in the MFR in Chessy, some allude to the work done on the professional project, in addition to the regional plan and the acquisition of job description flyers, as an resource to the numerical documentation. In the following quotation, the teachers in the vocational school Marc Seguin do stress the educational dimension, but it appears to be submitted to a capability for work first strategy: “(...) the idea was to get the pupils identified either as absentees, or not following in class, having make up for skipped classes or not paying attention in class, and to talk to them in private for a week, get them out of the classroom, and work with them on their individual aspirations, their professional project, giving meaning to their attendance in school and working on classes contents too. (…).” (Teacher, vocational upper secondary school, Vénissieux).

Consequently, in a capability perspective, this particular school is in an opposite position. Capability for work appears to come first while providing motivation to pupils. The issue of getting a job seems to condition the desire and the will to study. In other schools such as the agricultural school of Montravel or the Martin Luther King vocational school operators are first concerned with a will to study and an ability to interact within the school, in order to possibly develop capabilities for work later: “Take G.'s example, he is a typical case of failing kid who didn’t even want to study anymore, and then: bad grades over bad grades, he did not feel like studying anymore and gave up. Whereas now, he got successful again, so we got into a virtuous circle, good grades over good grades, he wants to study a little more, and so on. These are two extremes, we have great examples, and the bonus is already to get them to come to school, to feel happy within the walls. It is the first gain” (Teacher, Montravel’s Agricultural secondary school)

2.2 Capabilities for voice, education and work: necessarily intertwined

Our observations show a direct link between this weakness in terms of voice and the two other capabilities. Our case study suggests here that a weak performance at school is generally related to a poor capability for voice. This weakness in voicing results in difficulties when it comes to guidance choices: “at the beginning I wanted to do car mechanics but I have been sent in agriculture” (Manu, mission locale of Marmande). “At first I was supposed to go in general education but in cinema studies at the Montesquieu high school. The thing is that it was a very demanded high school with little room left, it was very hard to get into, it didn’t work out” (Mylène, Centre d’information et d’orientation of Blaye). We could easily multiply the examples; misfits and constraints in school-based guidance are present in nearly all of our interviews.

In the case of limited choices in education pathways, we find an instrumental conception of capability for work. By this, we mean that the transition to the labour market is conceived as a solution to school problems especially in the case of apprenticeship or on the job training. In that situation, all the functionings related to the work capability are not fully graspable. There is in that sense a strong relation between capabilities for education and work: weak performances in education result in fine in a weakened capability for work. In Aquitaine, perhaps more clearly than in Rhône-Alpes because they are already out of school, the youngsters we have met express it very clearly:

Manu & Guy

Manu and Guy are two dropouts we met at the “mission locale” of Marmande

What is your priority: employment or education?

Manu: Both, I put both because without education you can’t find a job, without a job no way to get training, it works in both directions

Guy: and without money you have no life

M: Exactly and now that’s the way it works. When we say we work to get blossomed first and for money in a second row, that might have been true a long time ago. Now we don’t work for blossoming but to earn money! To know if by the end of the month we’ll be ok, if we’ll have enough to eat rather than to get blossomed! You have to tell things the way they are and I think it’s gonna get worse and worse.

So you associate education and better job

M: Exactly!

So the priority is not necessarily to get a job?

G: Well, as I told you both are tied, it works like a train

That goes first by the education station?

M: Exactly.

Antoine

The case of Antoine is significant of the relation between the three capabilities. We met Antoine at the “mission locale”.

And the idea to start an apprenticeship, was that your idea?

I don’t like school, so… I asked for a BAC pro[8] but I have not been taken.

Do you regret it? Was that what you were looking for?

Yeah of course

How was that explained to you?

Well, first, how can I say, I did not have the good results, I was underscoring!

Jerôme

Jerôme has a degree in vocational education (woodwork), he tells us more about the weakness of voice:

They proposed me some firms.

And what you are proposed, does it really look like what you want to do?

It’s not exactly the same but it’s close.

And if you are not interested, do you say so? How does it work?

No, but after you can get a second thought about it. I do not necessarily agree but I think about it.

Have you ever said no?

Not so far

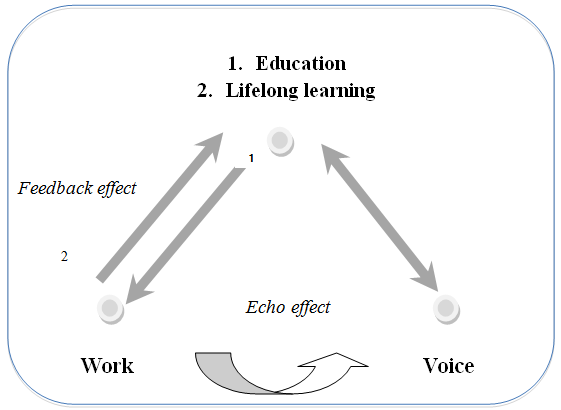

To sum up, we might say that in France the capabilities for voice and work are bound to the capability for education. A weak capability for education results in lowering down the two other capabilities. On the one hand, claiming and voicing requires some self-confidence and skills provided by education. Capability for voice is not given per se but comes out of a formal and informal education. On the other hand, the access to the labour market and a valuable job is in France strongly dependent on the kind of degree gathered in education. More, France’s continuous education and training system is known for being primarily accessed by already qualified workers. In that sense, a strong capability for education drags up and reinforces voice and work. But it should also be reminded that with the same performance at school, the children coming from well-off families get better diplomas than those coming from poorer families(Cacouault and Oeuvrard, 2003). The first are able to express themselves (they express their guidance preferences, they put pressure on the school institution and are able to mobilize their social networks, etc.) when the second are not able to do so as well. In that sense, the voicing resource acts upon the capability for education. A weak capability for work also leads in echo to a poor voicing capability. By feedback effect, this process impacts the capability to access lifelong education through training.

If nothing comes to counterbalance the initial individual/social situation, these effects tend to institutionalise in a permanent way. The educational background or the belonging to a given social category constraints the capability for voice[9]. In other words, the three capabilities are clearly bound together; they act upon each other in different ways that have to be understood in a temporal perspective.

2.3 Constraints to capabilities development and some good reasons to non take-up

In spite of the projects, numerous constraints remain within the schools. The absence and/or weakness of conversion factors limits the pupils capabilities’ enhancement.

2.3.1. Choice of what?

First of all, for some of the pupils interviewed, enrollment in education is not a choice. Besides, if indeed all projects allow for participation, it appears clear that some pupils can be prevented and/or dissuaded to participate. Other pupils also have to provide for themselves and find a job. Sometimes, tutoring hours get in conflict with the fact that “teachers and pupils are submerged with classes” (Head of school, Vocation secondary School). Long hours in transport between school and home can also represent a disincentive for pupils. At this point, it should also be reminded that the “schooling situation”[10] supporting the projects rarely leaves room for a deliberate choice of the children. These programs take place at a moment when the guidance choices have generally been already made, the pupils are engaged in their high school and if a constraint preexisted, it will remain. The projects have not been conceived to reduce the social/individual constraints but to prevent dropout. The only freedom given to the youngsters is the following: not to be forced to dropout whether they have chosen or not the school, the educational path or the diploma prepared. This freedom is supposed to increase their chance of getting their diploma at the end. So the question might only be: do this project increase or lower this embedded “freedom”?

The means to convert the given resources into capabilities might sometimes also be unexpected. For example, supporting a pupil until he gets his diploma even in a prescribed path (and based upon an initial adaptive preference) might allow him afterwards to pursue his educational career in a chosen way. The initial diploma acts as “sesame” and the support he gets might be considered as a conversion factor. By supporting a self-valued achievement in the medium term, the project finally increases a positive freedom.

But, the means associated to this support are among the first conversion factors. If the means are of the same kind than those producing the dropout, the project will probably not be capacitating. For example, using writing as a pedagogical mean might be inefficient if not destructive when it is managed with pupils showing difficulties in spelling. Some kids told us they needed help but were not able to find any usefulness in the proposed one: “It’s always the same thing. We see what is done inside the program and frankly I don’t need this. I can handle this myself. And you would like to have another kind of help? Yes maybe. Like what? Yes some… well in fact I don’t really know what kind of help” (Pupil in final year of vocational upper secondary school).

On the contrary, learning basic skills in vocational school and fighting against the temptation to promote a downgraded education for children at risk can increase the attraction and the pupils’ involvement in the program. Even if the fact of attending the program reflects an initial adaptive preference, it can work out well and the pupils might not drop out.

Regardless of the projects themselves, environments seem to have an impact as an exogenous variable on capability deployment (location of the school, pupil's problems). Such examples (jobs in addition to full-time education, geographical distance) tend to demonstrate that deploying capabilities for voice, work and education cannot be reduced to regional programs, and require horizontal policies developing conversion factors, on an individual but also on a social and environmental level. The interviews with pupils/operators/decision-makers illustrate that the conversion factors most likely successful are individual ones in those projects: tutoring, building-up self esteem, widening what is expected to be academic knowledge. Thus, additional funding from policy for urban cohesion, public health or family policy would provide some of the pupils with more opportunities and choices in their academic schooling.

2.3.2. Some very good reasons for non taking-up

Non taking-up should be a crucial issue when assessing such programs in a capability perspective. Youngsters have some very good reasons to refuse the “benefits” of the programs proposed to them. For example, in some schools, when pupils do not take advantage of a service, they bring forward the issue of time, the service being outside their timetable and adding up to already numerous hours of class.

Some services can also cast a specific identity on someone, “struggling pupil”, “drop out”, all derogatory labels. Targeting the program may also produce exclusion and this refers to the dark side of positive action. If they are a priori considered as “deficient”, or lacking in some respect, and not like responsible individuals, they might resist.

In their design as well as their implementation, the programs have to imply autonomy or take the risk of no guaranteed involvement. Pupils can be forced to participate but they do not benefit from the program: they do not perceive its aim and therefore reject it: “it feels like we have been sacked” (pupil in vocational upper secondary school, Vénissieux).

Pupils resort to these programs when they are directly focused on academic skills. On the opposite, activities that are not directly centered upon academics (cultural or artistic) can be a powerful motivation for some. According to them, a new routine is a source of motivation. Getting involved in activities where success comes more easily can trigger self worth, reassurance, and finally be a way to succeed at school later on. This could be seen as one of the indirect uses for such services.

An easy access to services is of equal importance. It is clearly a conversion factor linked to the way service is delivered to beneficiaries. Resources must be available easily if needed. It happens when access is open with a simple request, at any time and where their concerns are taken into consideration. Uneasy access to the program is also a valid reason for non taking-up

Related to the topic of the non take-up, a significant number of paths to dropout find their origin in a kind of withdrawal even before being allowed to access the program[11]. On the other hand, by trying to escape from educational vulnerability, the program may generate some forms of dependency to the given help. Withdrawing from this dependency may well be a kind of reflexive non take-up.

3 Conclusions and policy statements

The French case study allows us to draw some conclusions both on the governance of educational policies to reduce early school leaving and on the analysis of existing programs in terms of capabilities.

First conclusion to be drawn, there is no coherent public policy towards dropouts. Brought very recently on the political agenda above all in terms of public safety, the subject of early school leaving has not yet been addressed coherently by the French public authorities. Most of the recent efforts have been put on counting out precisely the number of dropouts. There are a large number of solutions and programs addressing this question but they remain scarce, discontinued over time and un-coordinated among actors. In particular, the lack of coordination can be pointed out both in terms of horizontal (intersectoral) and vertical (territorial) coordination. The public intervention at the national level remains segmented among the different ministries and administrations involved in fighting against early school leaving. The French public policies are also segmented between territorial bodies. Promoting anti-dropout and back to school programs supposes a high level of coordination between national and local public and private organisations. The complex and somehow poorly assumed process of devolution to territorial bodies (decentralisation) results in constant competency battles between the French state and these bodies. As shown here, the topic of early school leaving is one of such battlefields.

If the national framework of dropout policies can be criticised for its inefficiency and lack of strong political initiative, the local actors (street level bureaucrats and case manager) show a different picture. They appear to be strongly involved, easily collaborating and innovative. Directly confronted to the concrete difficulties of dropouts, they appear convinced of the necessity to overwhelm the sectoral/territorial barriers. In that sense, the idea of launching a national fund aiming at subsidizing local programs is an interesting initiative. But the local experiments appear to be too sensitive to the national/regional institutional context. Besides no framework of policy transfer has been created and the policy evaluation conducted is not taken in consideration as elements of judgment for a possible diffusion of local initiatives. So the local experimentations remain strictly local, totally experimental and limited in time and funding.

The studied experimentations in Rhône-Alpes and Aquitaine show different approaches in order to develop pupils’ capabilities. Yet, in spite of their resources, these plans reveal several constraints and the absence of conversion factors indispensable to capability reinforcement. They might suffer from excessive attention paid to a limited number of aspects – most of the time individual ones – like tutoring, self analysis and/ or identification and monitoring.

To promote action plans aiming at a global improvement of the dropouts’ capabilities, it seems necessary to work on transversal and integrated policies. Improving youngster’s capabilities in order to prevent or cure a massive phenomenon of school dropout (around 150.000 youngsters each year) supposes to take into account numerous factors related to school leaving such as transportation, health, housing, employment, social assistance, employment, substance abuse, etc.

A capability informed policy should necessarily be integrated and oriented towards horizontal/vertical coordination for what concerns its governance.

Also, a capability informed policy should pay a great attention to the non take-up processes. In depth studies of the reason why youngsters at risk or already dropped out do not make use of existing resources is central. In order to fully promote capabilities for voice, education and work, we need to know in details what prevents beneficiaries from using the institutional resources offered to them. Indeed before understanding conversion factors, it might be interesting to focus on the “non-conversion” factors.

References

Bernard, P.-Y., 2011, Le décrochage scolaire, Que sais-je ?, Paris, PUF.

Blaya, C., 2010, Décrochages scolaires. L'école en difficulté, Bruxelles, De Boeck.

Bloch, M.-C., and Gerde, B., 2004, "Un autre regard sur les décrocheurs. Le CLEPT, une expérience de rescolarisation en France", Revue Internationale d'Education 35 (Décrochage et raccrochages scolaires), 89-98.

Bonnery, S., 2004, "Un problème social émergent ? Les réponses institutionnelles au décrochage scolaire en France", Revue Internationale d'Education 35 (Décrochages et raccrochages scolaires), 81-88.

Bonvin, J.-M., and Farvaque, N., 2008, Amartya Sen, une politique de la liberté, Paris, Editions Michalon.

Bourdieu , P., and Passeron , J.-C., 1970, La reproduction : éléments pour une théorie du système d'enseignement, Paris, Les éditions de Minuit.

Cacouault, M., and Oeuvrard, F., 2003, Sociologie de l'éducation, Repères, Paris, La Découverte.

Céreq, 2012, Quand l’école est finie. Premiers pas dans la vie active d’une generation. Enquête 2010, Marseille, Céreq.

Glasman, D., and Douat, E., 2011, "Qu'est-ce que la "déscolarisation" ?", in La déscolarisation, édité par Glasman, D. and Oeuvrard, F., Paris, La Dispute.

Glasman, D., and Oeuvrard, F., 2011, La déscolarisation, La Dispute.

Lascoumes, P., and Le Galès, P., 2007, Sociologie de l'action publique, Collection 128, Paris, Armand Colin.

Rose, J., 2009, La non qualification. Vol. 53, Net.Doc, Marseille, Céreq.

Sen , A., 2000, Repenser l'inégalité, Paris, Éditions du Seuil.

Author’s

address:

Thierry Berthet / Véronique Simon

University of Bordeaux, Sciences Po Bordeaux

Centre Emile Durkheim,

11 allée Ausone, Domaine Universitaire

F-33607 Pessac Cedex,

France

Tel: ++33 5.56.84.68.06

Email: t.berthet@sciencespobordeaux.fr ; v.simon@sciencespobordeaux.fr