From the Lisbon Strategy to Europe 2020: the Statistical Landscape of the Education and Training Objectives Through the Lens of the Capability Approach

Josiane Vero, Centre d’Etudes et de Recherche sur les Qualifications, Marseille

1 Introduction

Severely hit by the unemployment, young Europeans are the first to experience the crisis. According to Eurostat data, more than 5 million young people in the EU are unemployed today. Between 2008 and 2010, this number increased by one million, which means that that one in five young people on the labour market cannot find a job (European Commission, 2011a). At the same time, the youth unemployment rate (at over 20%) is nearly three times higher than the rate for the adult active population. The extended effects of the crisis are deteriorating a situation that was already difficult for the young people. Hence, the youth long-term unemployment is on the rise: on average 28% of the young unemployed under 25 have been unemployed for more than 12 months. At the same time, the decrease in permanent jobs during the crisis has hit young people with a job disproportionally (European Commission, 2011a). However, the difficulties that young people are facing are not new, although the school-to-work process become increasingly time-consuming, complex and diversified (Gautié 1999, Serrano Pascual, 2000, 2004).

The extent of challenges and origins of youth unemployment vary from one Member State to another, but education and training has become, at the European policy-making level, as well as in most member states, one of the keys to enhancing employability. Since the 2000 Lisbon Council, the expectations raised by education and training have never been higher in European Union member countries: it is intended not only to protect youth by improving their employability, but also to give employers good returns on their productive investments as well as promoting employment and benefiting the community by boosting overall competition (Dayan & Eksl, 2007). Particularly influential was the discourse around the “knowledge economy” and its need for a highly skilled and adaptable workforce. A decade ago, the fifteen Member States of the European Union set a strategic goal for the European Union “to become the most dynamic and competitive, knowledge-based economy in the world, capable of sustaining economic growth, employment and social cohesion” (conclusions of the European Council of March 2000). Education and training was above all a linchpin in the implementation of this strategy and recommendations towards expanding the use of these policies had become a priority on the agenda of the European Union. Central to this endeavour was the strategy of employability, which can be regarded as a general trend aimed at increasing readiness to acquire the qualities that are needed by the labour market (Bonvin and Farvaque 2005, Spohrer 2011).

As a matter of priority, progresses towards educational targets are measured through the lens of the Open Method of Coordination (OMC). The OMC provides common objectives but leaves it up to each Member State to choose the ways and means of achieving them (Zeitlin and Pochet, 2005). In this context, the efforts of Member States are assessed by using performance indicators. Hence, the OMC is designed to achieve maximum impact on quantitative results. Since the launch of the European Employment Strategy (ESS) or later in the frame of the flexicurity strategy, some authors have made use of Amartya Sen’s Capability Approach and in particular on his key idea of ‘informational basis of judgement’ (Salais 2006, Bonvin et al. 2011; Vero et al. 2012) to reveal the postulates behind the decisions of those who designed the indicators at stake. In this chapter we shall discuss the limitations of the perspective developed in the “Education and Training” programmes whereby the development of skills may refer to “human capital” rather than to capabilities which emphasise people’s real freedom to choose the life they have reasons to value (Sen, 1999). We also aim to demonstrate the weakness of the angle whereby education and training are viewed in terms of adaptation to labour market requirements rather than in terms of real possibilities to act.

Taking up this plea to highlight the postulates behind the decisions of those who designed education and training benchmarks, the chapter starts out by giving a brief description of the Lisbon Strategy as well as the Europe 2020 Strategy focusing on the educational targets. The discussion will be centred on progress made and gaps remaining according to the European Commission yardstick. The subsequent section introduces the concepts of capability and Informational basis of Judgement derived from Amartya Sen’s Capability Approach (CA) in order to illuminate how indicators shape the perception of reality and highlight how statistical issues are enmeshed with policy issues. The chapter concludes by offering some thoughts on the progress that educational indicators should measure from the standpoint of the CA.

2 From the Lisbon Strategy to Europe 2020: progress made and gaps remaining

The inclusion of young people on the labour market has become a matter of growing importance on the agenda of the European Union, notably through the Education and Training Programme in order to fulfil the objective of a smart, sustainable and inclusive growth. This link is confirmed by many documents, as seen for example in calls from the European Commission “Europe’s future depends largely on its young people” (European Commission, 2011b, p.2). This section attempts first to spell out the main benchmarks that are put forward in the frame of the European Commission’s 2020 strategy (2010). Second, it examines on the one hand the extent to which the “Education and Training” program for the Lisbon Strategy has been achieved or could be achieved. On the other hand, it analyses how far member states are from the benchmarks endorsed in the frame of the “Education and Training 2020” strategy.

2.1 Setting benchmarks for cooperation in Education and Training

As in other policy areas, the open method of coordination (OMC) was the approach endorsed to tackle the education and training policy, whereby each member state is responsible for determining how to implement Education and Training Policies. By this means, cooperation is put into action by developing target-oriented regulation while also incorporating two already existing intergovernmental processes (namely the Copenhagen Process for vocational education and training and the Bologna process on higher education).

In 2001, following agreement within the Council of Education Ministers, the European Union’s Education and Training 2010 work programme was launched in the frame of the Lisbon Strategy. Member states and Commission working in this way agreed on indicators and benchmarks to monitor progress through evidence-based policy making. In this framework, the council in 2003 adopted five benchmarks, to be attained by 2010, to underpin this work of policy exchange (cf. Figure 1). The Education and Training 2010 programme (ET 2010) was supposed to deliver its first results by 2010. The cooperation was renewed in 2009 – when the assessment highlights that the Member States struggle to answer the challenge of the five European Benchmarks for 2010.

Hence, in May 2009, the council agreed an updated strategic framework for European cooperation in Education and training to be achieved by 2020 (known as ET 2020). Figure 1 reveals the benchmarks that underpin both strategic frameworks for European Cooperation in education and Training policy. There is by and large continuity with the earlier set of benchmarks. However, there will be new benchmarks on early school education and tertiary attainment among the young adult population; a broadening of the benchmarks on early school leaving and adult participation in lifelong learning with an increase in the target level of the latter. The 2010 benchmark on increasing the completion rate of upper secondary education has been discontinued on the basis of that it is closely linked to the maintain benchmark of early school leaving. The focus on early childhood education is the major innovation in ET2020: Besides, the focus on medium-level educational achievement (at least 85% of the upper-secondary education level) has been removed in favour of an objective focussed on high skills.

|

Figure 1 – Education and Training 2010-2020 strategic framework benchmarks |

|

|

ET 2010 for the Lisbon Strategy |

ET 2020 For Europe 2020 |

5. To have 12,5% of adults (25-64) participate in lifelong learning |

5. An average of a least 15% of adults (25-64) should participate in lifelong learning. |

Source: European Commission (2011c)

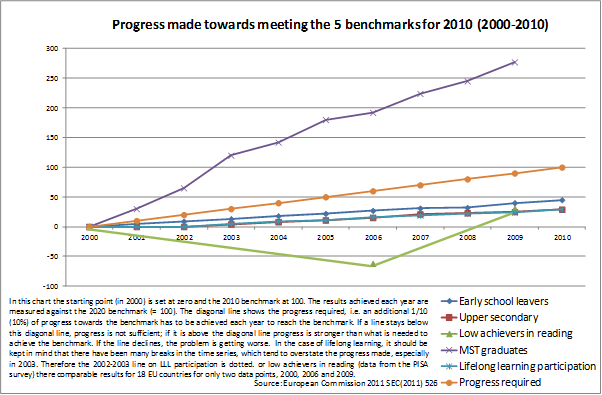

2.2 Progress made by ET 2010 is not what was expected

Figure 2 focus on the progress EU-27 has made in meeting ET 2010 strategic benchmarks, showing that despite further advances the EU performance fell short of targets. As the figure below illustrates, the share of university graduates in mathematics, science and technology actually is the only target out of five benchmarks to have already fulfilled ET 2010 objectives. As for the share of early school leavers, the EU-27 rate declined by 3.2 % to still stand at 14.4% in 2010 (European Commission, 2011b). Even if the average EU-27 union seems to be nearing the target, it should be noted that progress has been slow over the past decade (European Commission 2011c). In relation to the target of upper secondary attainment, EU-27 performance came to 78.9% of young people (aged 20-24) that have completed secondary level of education instead of the target of 85%. Despite the results related to lifelong learning participation have not ended up with the intended objective of 12.5%, the target level has increased to 15% over the next decade. Perhaps, the most obvious failure to reach the benchmark is the share of low performers in reading. The rate has been widened for 2020 to include also performances in mathematics and science which is expected to fall to about 15%.

Figure 2- progress made toward meeting the five benchmarks for 2010

2.3 The Europe 2020 Strategy: which educational targets are to be addressed in priority?

Of the five targets that the Education and Training 2020 program outline (Figure 1), the first two deserve close attention as these are integral part of the headline targets of the Europe 2020 strategy (European Commission, 2010a): 1) the share of early school leavers should be reduced from 15% to 10% by 2020; 2) at least the share of 30-34 year olds should have a tertiary degree or an equivalent qualification). Of course, it is too early to assess the progress in achieving both targets. However, looking at figures in 2010 would help to draw how far we still have to go to achieve the goals. This section focused on the path ahead and examines the limitations of both indicators.

How long is the way to attain the target of 10% of early school leavers?

In relation to early school leaving (ESL), what progress has been made across member states and what still needs to be done? Figure 3 illustrates the rate of early school leavers in the 27 member states and Switzerland i.e. the percentage of the population aged 18-24 having attained at most lower education and not involved in further education or training[1].

In 2010, using the definition mentioned by the European Commission (2003), statistics from the 2010 Labour Force Survey highlights huge differences among member states ranging from fewer than 5% in Czek Republic to more than 36% in Malta. A set of countries have already reached the 10% target, including the post-communist countries of Czech Republic, Slovenia, Poland, Lithuania as well as Sweden, Austria, and Switzerland. Other member states, notably the Netherlands, Finland, Ireland, Hungary, Denmark, Belgium, Germany and France are nearing the target. However, the four Mediterranean countries of Malta, Portugal, Spain and Italy can be regarded as the four main underperformers. In Malta over 36% of students leave school with at most a lower secondary degree. The various performances of member states can not be entirely laid at particular institutional frameworks of the education systems or at the number of years of compulsory schooling

However, Eurostat emphasizes that the early school leavers’ rates have to be interpreted carefully and it focuses on the need for improving the quality of data. Because of an heterogeneous application of certain concepts, the comparability remains rather restricted. As mentioned by Eurostat, it remains problematic and its quality raised some doubts: in term of reliability, it receives indeed only the poor mark C (Teedman H., Verdier E. coord., 2010). Comparability across countries is achieved in the European Labour Force Survey (LFS) through various regulations ensuring harmonisation of concepts, definitions and methodologies for all EU Member States, EFTA and candidate countries. However the results might lack comparability across countries due to the heterogeneity of the implementation of the concepts of participation in education and training in the Labour Force Survey. The chapter devoted exclusively to this European indicator details for each country the risks of measurement, such as some problems experienced with United Kingdom : “The United Kingdom classifies the first vocational trainings which last less than two years on level 3 of the ISCED [International Standard Classification of Education] whereas they should be logically on level 2 […] On this point, the international agencies correct or not these British statistics” (CERC, 2008, p. 18)”. These problems may disturb a comparative discussion.

Figure 3: Europe 2020 headline targets on education ; early school leavers[2]

How long is the way to attain the target of 40% of tertiary graduation?

The new target for tertiary attainment levels among the young adult population to be met by 2020 is the following: at least 40% of 30-34 year olds should hold a university degree. The new focus on this objective as a headline target of Europe 2020 raised questions as to how far are member-states from the goal of attaining this target?

Member states experience different challenge with regard to this benchmark as the distance to the target differs widely across member states. Figure 4 shows that some countries have already attained the objective and are in some case above target including Ireland, the Nordic countries, Luxembourg, Cyprus, Switzerland, France or the United Kingdom. Most of them have also seen this rate progress considerably in the last seven years (Etui, 2011). The largest European economy (Germany), however, is far from fulfilling the benchmark with a further increase of 12% and a long way still lays ahead for some others countries like Romania, Italy, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Malta or Portugal, Austria. All these countries are far below the 20% objective, i.e. only about half way to reaching the target. According to Roth and Thum (2011, p.2), the objective of doubling the number of tertiary graduates in just one decade seems to be so ambitious that “realistically this will not be possible for any of these countries without a severe deterioration in the quality of such education”. Meanwhile, Cedefop (2010) forecasts quite positive progress towards this headline and argues that the crisis may encourage more students to further their educational path due to lack of employment opportunities. Regardless of the benefits of such an arrangement in terms of personal development, it is by no means a given that more education will increase labour market opportunities and go ahead to the intended greater economic spinoffs. Besides, while some focuses very much on higher education for a knowledge-based economy (Cedefop, 2010) and more generally knowledge-driven growth, it may be argued that the link is not a straightforward one since there is not necessarily an obvious correlation between the two. The low link between the share of graduates aged 30-34 and the total added value of the knowledge-intensive sector seems to be confirmed by the evaluations made by Theodoropoulos (2010). While this outcome does not support the conclusion that there is no relationship between theses two indicators, it is clear from the foregoing that several factors play a decisive role, and it is important to stress that that other factors may include the quality – and not just the quantity – of graduates alongside with adequate levels of investments. Hence, following ETUI (2011), the quantitative benchmark of 40% is somewhat weak without adding additional benchmark for the quality of education.

Figure 4: Share of 30-34 year olds with tertiary education attainment[3]

3 The normative assumptions behind the strategic framework for Education and Training 2020

Our purpose is here to examine the normative assumptions behind the educational benchmarks endorsed at the European policy-making level. What reasoning do they hold and what values do they reveal? How useful are they in enhancing our way of understanding the problems and obstacles that young people meet during their qualification and entry on the labour market? How effective are they in improving our concrete knowledge of these barriers, in making visible their real freedom to choose the life they has reason to value, i.e. their capabilities? Drawing on an epistemological analysis founded on Amartya Sen’s capability approach and in particular on his key idea of ‘informational basis’ of judgement, this section identifies the normative thread of the indicators promoted in the educational field by the European commission, which gives employability precedence over capability.

3.1 The normative thread of quantitative indicators

Indicators are often pictured as neutral or scientific tools insofar they are “evidence-based”. Although indicators can provide valuable information, they also have limitations: they are inextricably rooted in a number of implicit normative choices and selections, embedded with values. In consequence, what is measured is what matters, what is cared about. Clearly not all indicators are similar. What they have in common is simplifying complex situations.

The work of Amartya Sen enables us to grasp the normative thread of quantitative indicators thanks in particular to the key idea of ‘informational base of judgement” (IBJ). This “identifies the information on which the judgment is directly dependent and – no less important – asserts that the truth or falsehood of any other information cannot directly influence the correctness of the judgment. The informational basis of judgement in justice thus determines the factual territory over which considerations of justice would directly apply” (Sen 1990:11).

By giving Member States an incentive to improve their score in the ranking list of benchmarks and quantitative objectives, performance indicators establish priorities. Hence, what is be measured through the use of benchmarks is also what will be achieved in practice and what is not measured will therefore more likely to be overlooked. These indicators are therefore merely revealing the priorities of the education and training policy. Indeed, the decision to focus on certain data and to exclude others significantly impacts on the very content of public policies and on the way to define their efficient implementation (Salais, 2006; Bonvin et al. 2011; Vero et al. 2012). With the indicators, emphasis is also placed on the relationship between description and prescription. Describing situations means making choices and attracting the attention of public decision-makers and public opinion to the issues regarded as most important. Devising indicators is not merely aimed at describing what exists or analysing practices; it is first and foremost a policy move connected with a prescriptive dimension.

It is therefore necessary to ask ourselves about the normative and informational foundations of the educational indicators through the lens of Sen’s epistemological principles. Our intention, then, is to shed light on the normative logic underlying these indicators.

3.2 A wider perspective behind educational targets: raising the employment rate to 75%

Figure 2 shows the headline targets in the five distinct areas that the European commission’s 2020 has put forward: 1) Employment: (2) research innovation; (3) climate change and energy; (4) education; (5) poverty. Employment has been placed at the core of the Europe 2020 strategy and as mentioned in the figure 2, education is put forward as a fundamental driver of employment. The rationale that underpins educational benchmarks is that more education will better meet labour market needs.

|

Figure 5 – EU headline targets for Europe 2020 |

|

|

Area |

Target |

|

1. Employment 2. Research innovation 3. Climate change and energy 4. Education 5. Poverty |

|

Source: Europe 2020

By drawing on the Europe Strategy for smart, sustainable and inclusive growth, the emphasis on raising educational outcomes is line with the desire to raise employment rates which lies at the core of the European Strategy and more particularly to guidelines 7 ‘Increasing labour market participation of women and men, reducing structural unemployment and promoting job quality’. Educational indicators are prompted by the need to increase rate in the short and middle term as it is clearly stated in January 2011 in a communication entitled “Tackling early school leavers: A key contribution to the Europe 2020 agenda” which mentions: “Reducing Early School leaving is a gateway to reaching other Europe 2020 targets. By impacting directly on the employability of young people, it contributes to increasing integration into the labour market and so to the achievement of the headline target of 75% employment rate for men and women aged 20 to 64” (European Commission, 2011b, p.2). Increasing the proportion of 30-34 year olds having completed tertiary to at least 40 % follows the same logic: “measures taken in the education and training sector will contribute to […] increasing employment rates” ( European Council, 2011 p.2)

Hence, as a matter of priority, the ultimate objective of educational policies is to maximise the employment rate at the macro level, as mentioned in figure 5. Rogowski et al. (2011:) reminds us how announcing a rising employment rate is much more satisfactory in terms of communication than undertaking far-reaching action that truly improves educational conditions as well as employment situation but fails to grab media headlines. Such a priority contributes to place employment quality on the back burner and enforce acceptance of the idea that a poor-quality job is worth more than no job at all. In actual fact, from a synchronic perspective, employment quality at a given point in time appears to be a central issue, whereas from a dynamic angle a bad job may be justified because it can represent a springboard towards lasting integration into the workforce.

In addition, by focusing on the increase of the employment rate, the general theme of the Europe 2020 strategy is to improve the supply side of the employment equation via education and training development. Its message is rather one-sided, centring on the supply of work from individuals, i.e on employability, leaving demand of work in the blind spot. Although the development of employability is a notion which has itself been subject to numerous definitions (Gazier 1990; Bonvin and Farvaque 2006), employability is in fact mainly used as a category of economic policy aiming at worker’s adaptability. In close correlation with that, employability is aimed at fostering an individual’s ability to gain or maintain employment by stressing the responsibility of the youth to participate in education and training. This one-sided focus on responsibility is ambiguous insofar as it encourages the individual's freedom of action; but it means at the same time that young adults themselves may now have to shoulder the blame for not undergoing education, improving their skills and gaining an employment.

As a matter of priority, the ultimate objective of educational policies is twofold: first maximising the employment rate at the macro level and second reaccelerating the reintegration into the labour market at the micro level without taking account the person’s specific circumstances (i.e. his or her physical, psychological or other ability to work, to balance work and family life, etc.). This strategy is aimed at fostering young people's employability by stressing the responsibility of the individual to participate in education and employment. This indicator therefore views education from the angle of adapting to labour market requirements. Its message is rather one-sided, centring on the supply of work from individuals leaving demand for work to the initiative of companies, framed by a policy of deregulation. This focus bears the danger of increasing employment precariousness rather than enhancing young adult’s capability for work.

Like other watchwords at the European level, “employability” seems to have acquired the status of magical concept that appears to provide universal solutions. Policies on inclusion to the labour market that promote “employability” suggest individual adaptability and up-skilling as the cure for persisting exclusion. This discourse goes alongside the promotion of the “human capital” mindset which stressing the responsibility of individual to participate to education and employment. The subsequent section will outline the “human capital” approach against the capability approach.

3.3 Human capital mindset against the capability approach

There are many ways to measure progress toward education and there is no consensus as to which indicator is the best. The choice of indicator depends on data availability and also on forms of education-employment relationship considered important. According to Robert Salais, ‘the upheaval introduced by the capability approach relates to the choice of the yardstick by which collective action (policies, legislation, and procedures) should be devised, implemented and assessed. For Sen, the only ethically legitimate reference point for collective action is the person, and specifically his situation as regards the amount of real freedom he possesses to choose and conduct the life he wishes to lead’ (Salais, 2005: 10). This perspective sets out an ambitious way forward for public policy-making, which is not merely about enhancing people’s adaptability to labour market requirements, i.e. their employability, but first and foremost about promoting their real freedom to choose the work they have reason to lead, i.e. their capability for work (Bonvin, Farvaque 2005). Collective action is therefore expected to develop opportunities for people while acknowledging their free choice with regard to ways of living or being.

Insisting on real freedom means, on the one hand, going beyond an approach based on educational rights and resources. One cannot take for granted that educational resources and rights provision (targeting early school leavers or aiming at increasing the access to tertiary education, etc.) lead to increased capabilities. Thus, the age of starting compulsory education, the right of access to tertiary education, or a lifelong learning right is an important resource for the development of young’s capabilities. But it is not, however, enough to ensure their capability for work. Among the factors which influence the exercise of this freedom, the role that educational and employment institution plays (in terms attractiveness and accessibility of educational paths together with quality and the ability to match labour market opportunities), companies' recruitment policies, the vulnerability of jobs to the vagaries of the economy, etc. are central. These factors of conversion of resources into capabilities may be individual, institutional or social. The opportunity dimension of freedom is here crucial. Insisting on real freedom means, on the other hand, making the distinction between what young adults do (functionings) and they are really free to do (capabilities). A same functioning can result from the availability or the absence of real freedoms. For example, gaining employment can either be imposed; or it can be discussed with the employment agency as a part of a broader range of options and finally chosen as the best available option. Although the outcome may be the same, the process in question is very different. From a capability perspective, freedom is not only a matter of opportunity, but also of process that may be assessed into a synchronic and dynamic perspective.

By contrast, the aim of the European normative foundations is to increase the returns from human-capital investment by stressing on the responsibility of the individual. All too often, especially in the European reasoning, variability in outcomes is said to be due to inherently individual properties. The issue as to whether to conditions are actually met in order that young adults can exercise their responsibility is a blind spot. According to that reasoning, education is a profitable form of investment for the individual and for society that creates gains in productivity, thereby increasing wages and consequently individual employability. However, the relationship between Education à Productivity à Wages relies on neoclassical hypotheses[5]. The problem with this theoretical picture is quite simply that it does not match the reality. Certainly part of the success of the unequal inclusion is due to individual factors like the human capital. Other inequalities, however, although related to the person, are due to objective social or institutional factors. These factors should be included in public action and its assessment through indicators. However, as it stands the ultimate objective of educational policies is twofold: first maximising the employment rate at the macro level and second reaccelerating the reintegration into the labour market at the micro level without taking account the person’s specific circumstances (i.e. his or her physical, psychological or other ability to work, to balance work and family life, etc.). This orientation certainly meets the economic requirements of responsiveness and flexibility, but it neglects the temporal and social factors shaping young’s pathways, as well as their personal preferences and choices at the core of the capability approach.

The capability approach draws our attention to two different but complementary ways of looking at education: (1) on the one hand, as a good in itself, i.e. aims worth pursuing for their own sake, and (2) on the other hand, as a means of gaining access to new possibilities and developing one’s potential (Lambert and al. 2012). In the first one, the focus is on young educational rights and the processes whereby these rights are converted into educational accomplishments (individual, familial, organisational and institutional factors leading to education success) and the measurement of these educational accomplishments. In the second instance, the focus is on the achievements made possible by learning and training, especially as far as youth’s capability for work is concerned.

In the first instance, contrary to what European union indicators favours (rate of early school leavers, share of tertiary educational attainment), capability approach places emphasis on the issue of converting resources into accomplishments as well as the real freedom to choose (Sen, 2009). Although the European commission advocates that “the reason why young people leave education and training prematurely are highly individual” (European Commission, 2011), policy-makers need to be mindful of the fact that the phenomenon of early school leaving is a matter of accumulation which entails a wide range of conversion factors causing obstruction or enhancement of . Identifying these factors is paramount to enhance the capabilities of young adults that are particularly hit hard by the economic downturn. These factors may be individual, organizational, institutional or social. For instance, evidence of the influence of social and cultural background on students’ educational results is provided both by data from the Bologna Process and from the PISA 2009 (OECD 2010, ETUI). Data shows that the educational level of parents has a clear influence on the tertiary enrolment of their children’s (Eurostat, 2010). This amounts that, alongside with a lack of opportunities, family background plays a role not only in terms of financial support alone but also in relation to social, cultural, geographical aspects.

In the second instance, contrary to what European Union prescribes through the employment rate, i.e. the adaptability to labour market requirements, the capability approach places as much importance on training as a key to enhancing people’s possibilities to exercise a job they have reasons to value. Hence, not only is the phenomenon of early school leaving problematic because of the waste of potentially valuable human capital which ought to contribute to the achievement of full employment; it constitutes a present and future priority also because the young people who drop out school are victims of social situations which cause them to run higher risks of achieving a wide range of capabilities. Moving over to a capability approach-inspired vision would entail a number of developments. First the employment quality issue would need to be integrated into a synchronic and dynamic perspective, referring back to ‘an analysis of the scope of working and living possibilities offered by inclusion in employment’ (Salais and Villeneuve, 2004: 287). Moreover, by contrast with the normative foundations of the European perspective, the CA emphasizes how the main question is not whether workers are more flexible or adaptable. Rather, it is whether the conditions are properly met (or are guaranteed) for young adults to possess real freedom to learn, to aspire, to voice one’s concerns and to work. According to capability approach such real freedom is a precondition of an active inclusion of young people.

4 Conclusion: Towards more capability-friendly indicators

It is surely essential and highly desirable to avoid a stance in which education and training are considered solely from the standpoint of the need to meet economic and employment targets (as it is the case in the Europe 2020 strategy and its target of 75% employment rate in all EU member states), and in which policies designed to achieve social integration of young people look no further than the adaptation to the labour market. Rather, performance should be evaluated in terms of capability for work.

The shift of focus may be modest, but it really has wide-ranging implications when designing, implementing and assessing employability policies. The first conclusion to be drawn from the above discussion is that it is important to guarantee that measures that affect supply (in terms of education and training, vocational guidance, etc.) should be complemented by demand-driven educational and training programs. As mentioned by Bonvin and Orton (2009), what is suggested is not an unconditional respect of the beneficiaries’ freedom to choose, but the opportunity opened to them as well as to youth representatives, to take an active part in the design and implementation of employability strategies and to make their voice heard. From the CA, this possibility to voice one concern should be evaluated. Secondly, no matter how relevant the individual action statement may be, without support of adequate conversion factors, it runs the risk of having an adverse impact. With regard to this issue, it is also important to ensure that measures which support and encourage young people to take starter employment are combined with programmes to improve the quality of life (decent living conditions, economic independence, etc.). As a result, this implies that public action is to be also assessed along these additional dimensions in the frame of a situated approach, i.e. an approach centred on the role that institutions play in specific situations (Salais et al. 2011). Thirdly, employability policies should give equal weight to the quality and quantity of jobs. The European commission does signal in its 2011 work programme an intention to devote more attention to the issue of employment quality. However, headline indicators of the Europe 2020 allow no scope for measuring how policies can affect the quality of employment while it is a core yardstick against which public action is to be assessed when moving over to a capability approach-inspired vision.

In such a perspective, it is important to look at a comprehensive set of dimension, which entails to combine data from different sources and levels, by supplementing information from an administrative register by surveys and other types of sources. In order to translate this perspective into an analytical tool that can be used for employability assessment, we may suggest, for example, to supplement surveys on Education, training, guidance or employment paths at the individual level by information received from households, employment agencies, educational institutions, firms and even by macroeconomic information that may inform on 'net increases' or ‘net destruction’ of employments, etc. The role of linked data in advancing understanding of labour markets is well-established (Bryson, Forth and Barber, 2006). For example, linked employer employee surveys are empirical tools that may contribute to improved freedom measures (Lambert and Vero, 2012). Of course, substantive knowledge of the longitudinal pathway is also essential. The most part of European indicators has been limited to information spaces that are static with the exception of some transition indicators (Bonvin and al. 2011; Vero and al. 2012). But educational outcomes, school-to-work transition as well as employability policies would be best understood in an evolutionary perspective. The capability approach calls for an understanding of the educational outcomes that are attached to the individual pathway. The availability of longitudinal data on school-to-work transition would make it possible to adopt dynamic indicators. Focusing on the need of individualised follow-up is a way of coming to grips with the reality of long-standing, complex and diversified processes of school-to-work transition. These ideas, which are still struggling to take shape in European circles, call for an overhaul project of European surveys and indicators in favour of the development of real freedom of action for all young European.

References

Abbateccola, E., Lefresne, F., Verd, J. M. and Vero, J. eds (2012), Individual working lives viewed through the lens of the capability approach. An overview across Europe, Special issue of Transfer, 18(1).

Bonvin J-M. (2012), “Individual working lives and collective action. An introduction to capability for work and capability for voice”, Tranfer, 18(1) pp 9-18.

Bonvin J-M, Orton M. (2009), “Activation policies and Organizational Innovation. The Added Value of the Capability Approach”, International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, Vol 29, No 11-12.

Bonvin J-M. Farvaque N. (2005) “What Informational basis for assessing jobseekers?: Capabilities vs. preferences”, Review of Social Economy 63(2): 269–289.

Bonvin J-M, Moachon E., Vero J. (2011) “Déchiffrer deux indicateurs européens de flexicurité à l’aune de l’approche par les capacités”, Formation Emploi, 113, pp. 15-32.

Bryson A. Forth J., Barber C. (2006), “Making Linked Employer-Employee Data Relevant to Policy”, DTI Occasional Paper No. 4, 155 p.

Cedefop (2010), Skills supply and demand in Europe – Medium-term up to 2020, Publications Office, Luxembourg, 120 p.

CERC (2008) Les jeunes sans diplôme, un devoir national, Rapport n° 9, La Documentation Française

Clasen J and Clegg D (2006) “Beyond Activation: Reforming European Unemployment Protection Systems in Post-Industrial Labour Markets”, European Societies, 8(4): 527–553.

Cressey P (1999) New Labour and employment, training and employee relations. In: Powell M (ed.) New Labour, New Welfare State, The ‘‘Third Way’’ in British social policy. Bristol: Policy Press, pp.171–190.

ETUI (2011), Benchmarking Working Europe 2011, Brussels: ETUI, 112 p.

European Commission (2003), Mid-term review of the social policy agenda, Communication from the Commission to the European parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of Regions, Brussels, 02.6.2003, COM(2003) 312 final, 28 p., available at http://eur-lex.europa.eu/smartapi/cgi/sga_doc?smartapi!celexplus!prod!DocNumber&lg=en&type_doc=COMfinal&an_doc=2003&nu_doc=312 (accessed 5th June 2012)

European Commission (2010a), Europe 2020, A strategy for smart, sustainable and inclusive growth, Communication from the Commission, Brussels, 3.3.2010, COM (2010) 2020 final, 34 p., available at http://ec.europa.eu/europe2020/documents/related-document-type/index_en.htm (accessed 5th June 2012)

European Commission (2010b), An Agenda for new skills and jobs: A European contribution towards full employment, Strasbourg, 23.11.2010 COM(2010) 682 final, http://ec.europa.eu/education/lifelong-learning-policy/framework_en.htm

European Commission (2011a), Youth Opportunities Initiative, Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions, Brussels, 20.12.2011, COM(2011) 933 final, 13 p.

European Commission (2011b), Tackling early school leaving: A key contribution to the Europe 2020 Agenda, 10 p., Communication from the Commission to the European parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of Regions, Brussels, 31.1.2011, COM(2011) 18 final, 10 p. available at http://ec.europa.eu/education/school-education/leaving_en.htm (accessed 5th June 2012)

European Commission (2011c), Progress Towards the Common European Objectives in Education and Training. Indicators and Benchmarks 2010/2011, SEC (2011) 526, 191 p., available at http://ec.europa.eu/education/lifelong-learning-policy/indicators10_en.htm (accessed 5th June 2012).

Eurostat 2010, Online Statistics database. http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/portal/page/portal/statistics/ themes

European Council (2000), Conclusions of the European Council of March 2000

European Council (2009), Council Conclusions of 12 May 2009 on a strategic framework for European cooperation in education and training (ET 2020) [Official Journal C 119 of 28.5.2009].

European Council (2011), Conclusions on the role of education and training in the implementation of the ‘Europe 2020’ strategy [Official Journal C 70/1 of 4.3..2011].

Gautié (1999), “ promoting Employment for Youth : A European Perspective” in Browers N., Sonnet A., Bardonne L: Preparing Youth the 21st Cenury – The Transition from Education to the Labour Market, OECD, Paris.

Lambert M., Vero J. (2012), “The capability to aspire for continuing vocational training within French Firms. How the environment shaped by training corporate policy plays a decisive role”, International Journal of Manpower, Vol. 33, forthcoming.

Roth F., Thum A-E. (2010), “The Key Role of Education in the Europe 2020 Strategy”, CEPS Working Document, 338, October, 16 p.

OECD (2010), Pisa 2009 results, Overcoming social background: equity in learning opportunities and outcomes, Volume II, Paris.

Theodoropoulou, S. (2010), “Skills and education for growth and well-being in Europe 2020: are we on the right path?”, EPC Issue Paper, n° 61.

Pochet, P. (2010), “What is wrong with EU 2020?”, ETUI Policy Brief. European Social Policy N02/2010.

Poulain E. (2001), “Le capital humain, d’une conception substantielle à un modèle représentationnel”, Revue Economique, 52 (1), pp 91-116.

Salais R (2005) Le projet européen a` l’aune des travaux de Sen. L’E´conomie politique 3/2005, 27: 8–23.

Salais R (2006) Reforming the European Social Model and the politics of indicators. From the unemployment rate to the employment rate in the European Employment Strategy. In: Jepsen M and Serrano A (eds) Unwrapping the European Social Model. Bristol, The Policy Press, pp.213–232.

Salais R., Villeneuve R. eds (2004), Europe and the Politics of Capabilities, Cambridge University Press.

Rogowski R., Salais R., Whiteside N. (2011), Transforming European Employment Policy. Labour Market Transitions and the Promotion of Capability, Cheltenham UK, Northampton, 288 p.

Serrano Pascual A. (2000), dir, Tackling youth Unemployment in Europe, Bruxelles: ISELambert M.,Vero J.,

Sen A. (1990), “Justice : Means versus Freedom”, Philosophy and Public Affairs, Vol.19, N0.2, pp.111-121

Sen, A.,(1999), Development as Freedom. Oxford, Oxford University Press.

Sen, A. (2009), The Idea of Justice. London: Allen Lane

Teedman H., Verdier E. coord. (2010), Les élèves sans qualification: la France et les pays, rapport pour le Haut Conseil de l’Education, December, 168 p.

Verd, J.-M. and Vero, J. (eds) (2011), La flexicurité à l’aune de l’approche par les capacités, special issue of Formation Emploi, 113, Janvier-Mars.

Vero J., Bonvin J-M, Lambert M., Moachon E. (2012), “Decoding the European dynamic employment security indicator through the lens of the capability approach. A comparison of the United Kingdom and Sweden”, Transfer, 18(1) 55–67.

Zeitlin J., and Pochet P. eds (2005). The Open Method of Co-ordination in Action: The European Employment and Social Inclusion Strategies. Brussels: P.I.E.-Peter Lang.

Zimmermann B. (2012), “Vocational Training and Professional Development”, International Journal of Training and Development, Vol. 16/3, September 2012, forthcoming.

Author´s

Address:

Josiane Vero

CEREQ

10 Place de la Joliette BP 21321

13567 Marseille Cedex 02

France

Tel: ++33 4 91 13 28 28

Email: vero@cereq.fr