Problem Solving Policing: Views of Citizens and Citizens Expectations in Germany

For the last two decades American police experts developed new police philosophies in order to tackle more successful the increasing crime problems. Community Policing tries to improve the cooperation between the population and the police and to increase the trust in the police. A crucial factor is a meaningful cooperation between the police and the citizens. Problem Oriented Policing aims at structural changes in the organisation and the procedures of the police in public. The police have to investigate the hidden problems and conflicts of an individual offence and to create proactive and long term concepts for the social area of conflicts beyond the specific case. It is doubtful whether these philosophies can be implemented in Germany since the legality principle prohibits meaningful, trustworthy relationships between citizens and police officers. However, if one examines the results of surveys on citizens views and expectations towards the police one finds that the majority of the German citizens favour the postulates of community and problem oriented policing. They expect through these measures an improvement of their life situation in the community and the feelings of safety. If one takes these results seriously one has to question if the legality principle is still appropriate. It seems to hamper new, more promising policing styles which seem to improve life of it's citizens and reflect what the citizens want and expect from their police force.

Introduction

The new police philosophies community policing and problem oriented policing have started a lot of discussion in countries outside far the United States of America where these concepts were developed. This is mostly due to the fact that the results of these new strategies sound very promising (Skogan 1996, 25).

It seems to be rather easy to transfer these philosophies and insights of community and problem oriented policing results to countries in which law enforcement and criminal justice administration are guided by the so-called opportunity principle. Under the opportunity principle it is in general agencies officially allowed or they are even entitled by law to abandon any persecution, to dismiss a case formally, to enter an alternative way of dealing with the case (e.g. to transfer it to psychiatric authorities or youth agencies), or to charge the culprit eventually with a lesser offence than that originally prosecuted. In some of the States this discretionary power is even more or less completely given to the police authorities or individual police officers on the beat.

On the contrary will countries, in which law enforcement agencies and criminal justice administrations are guided by the so-called legality principle, face many difficulties when trying to introduce community- or problem oriented policing. These philosophies and practices aim at improving the relationship between the authorities, the citizens, and the communities. This relationship implies the development of social-psychological bonds based on mutual exchange relations and trustworthiness between the police and the citizens. This relationship is supposed in the long run to improve the quality of life in the community and to make the living conditions for the people more secure. The legality principle stays in stark contrast with those goals and principles. It requires, when strictly administered, that every agent of the law enforcement agencies and the administration of criminal justice treats every case formally and officially and has no discretion whatsoever. Whenever there is suspicion that a crime may have been committed these persons have to start an official procedure, to record the already known details of the case, to start an investigation, and to charge the suspect eventually with the relevant counts before a criminal court.

Nowadays, nearly no system adhering to the legality principle, like Germany, Austria or Switzerland, does administer it in practice in the traditional strict way anymore. There were partly official laws introducing exceptions, partly leeway opened by court decisions or by practitioners guidelines. This development gave prosecutors and judges a couple of new possibilities to deal with cases and suspects in a discretionary manner. But the police were as a rule not entitled to act likewise. They have, for example in Germany, no legal power to decide by themselves on how to proceed a case. Quite contrary are the police officers required to take note of every case, and to report it to the public prosecutor by adding all the existing files and evidence. Only very minor traffic transgressions are excepted, for instance parking violations, where the police officer on the beat has some discretion whether to give only an immediate oral warning, to write a ticket or to enter a special procedure (Bußgeldverfahren) to be handled further by the traffic authority.

Even though the police in Germany have in the field of order maintenance and the safeguarding of public life the usual discretionary power, one has to conclude that the theories of community policing and problem oriented policing may be doomed to fail in countries with the legality principle. In many everyday situations the aspects of law enforcement and order maintenance are intrinsically intertwined. In some circumstances police officers get complaints about events that formally fulfil all the legal requirements of a criminal offence but are negligible in substance. There may typically exist no need for law enforcement, but only some friendly, direct advice and perhaps immediate restitution or reconciliation. Under the legality principle the police officer has only a bad choice: if he does not act formally, he runs the risk of getting charged himself in case his decision is being reported to the prosecutors office. On the other hand if he acts every time formally, he can not built up trustworthy and good relationships with citizens and the community.

However, when we examined surveys in Germany about what the citizens want from their police we found that the German people have wishes and expectations which represent almost exactly what community- and problem oriented policing postulate. Therefore one can conclude that the implementation of these new policing philosophies would not be possible without a substantial modification or the abandonment of the legality principle. The modifications or the abandonment would allow that the concepts of community- and problem oriented policing could be implemented in Germany, Austria, and Switzerland, improve life for its citizens and fulfil the wishes and expectations of the citizens toward their police.

Development of Community Policing and Problem Oriented Policing

The traditional style of policing was to keep public peace and order, to enforce laws, making arrests, and to provide short-term solutions to occurring problems. This concept stood in contrast to the policing style proposed by Sir Robert Peel for a professional police force in Great Britain which was passed by the British Parliament in 1829 and which stressed the preventive nature of the new law: "... the principal object to be attained is the prevention of crime. The security of persons and property will thus be better effected, than by the detection and punishment of the offender after he has succeeded in committing the crime" (Radzinowicz 1968, 163). The principles of Peel's proposed policing can again be found since the early 1980's when community policing emerged as the dominant direction for new ways in thinking about policing. Parallel to the reintroduction of the concept of community policing developed Goldstein 1979 and later Eck and Spelman 1987 the concept of problem oriented policing. Even though these two concepts, community policing and problem oriented policing, are analytically separate and distinct, argue Peak and Glensor (1996, 69) convincingly that they are complementary in substance, and can be operated together. Peak and Glensor (1996, 68) coined the term "community oriented policing and problem solving" (COPPS) in which they try to integrate the two concepts (see for Problem-Solving, Moore 1996, 2, 13). One important aspect so far is the communities´ and the citizens welfare and their working together with the police. This is well in line with an argument already put forward by Sir Peel: "The police are only members of the public who are paid to give fulltime attention to duties which are incumbent on every citizen in the interest of the community welfare" (cited in Melville Lee 1901). One may ask, however, whether at all, and how well this cooperation between communities and the police works in modern, industrialized and socially more or less fragmented societies (see also Moore 1996, 7). A possible way to measure this question seems to ask citizens about their attitudes towards, and their experiences with, the police. Survey results and other material pertaining fully and specifically to community policing and problem oriented policing are seemingly nonexistent. In this article we take therefore a rather broad view. We will consider how the public views and perceives the police and their work in general, what the expectations of the citizens are towards the police, and how actual policing styles or manners are affecting (inter alia) the citizens levels of fear of crime and feelings of insecurity in their neighbourhoods. We will then try to interprete those results with regard to our particular topic.

Community Policing

Based on the assumption that in today world the working together between the police and the citizens is almost nonexistent, was the concept of community policing developed in the early 1980's. Among the reasons for the rather loose, sometimes tense or even bad relationship between the police and the community were a lack of trust in and scepticism about the police. This was partly due to the fact that in the past in many regions, cities, places etc. close personal contacts between the police authorities or individual police officers and the citizens, apart from the handling of concrete events, were generally rather scarce. However, in order to get background knowledge about the typical characteristics of the population and their living environment, which was seen as essential to reach an improved crime clearance rate and to better prevent future crimes, a close relationship and good everyday cooperation between the police and the community members seemed absolutely necessary. Therefore the concept of community policing aims to reunite the police with, respectively to immerse them into the community. It is a holistic concept, definitely surpassing technocratic solutions as liked by bureaucratic apparatusses. It is also critical towards marketing conceptions as they were proposed earlier, e.g. Police-Community-Relations. Trojanowicz and Carter (1988, 17) describe the basic philosophy of community policing as follows: " It is a philosophy and not a specific tactic; a proactive, decentralized approach, designed to reduce crime, disorder, and fear of crime, by involving the same officer in the same community for a long term basis".

For the purpose of our analysis we summarize the principles of community policing as following:

-

Community policing is based on the assumption that there is no real distinction between the substantive function of policing between members of the general public and particular office-holders. To put it in a slogan: police are the public and the public are the police. That means that the police officers are just those who are paid to give fulltime attention to the duties of every citizen (Peak and Glensor, 1986, 73).

-

Community policing is based upon commitment for far reaching, broad problem oriented service. It is much more than just an addition to the traditional event oriented policing style.

-

Community policing is based upon an organizational decentralization and on the reconstruction of police work in favour of a two-way-communication between the police and the citizens (Sparrow 1988, 8-9).

-

Community policing requests that the police, representing but one department among many others responsible for improving the quality of life, respond towards the wishes of the citizens and, even in the absence of crime and disorder, to whatever problems disturb the community most.

-

The police and their work serve as a catalyst to organize the community and to enhance public cooperation amongst the citizens.

-

Community policing concentrates its attention on signs of disorder or incivility such as vandalism, graffiti, abandoned housing, trash, etc. (Wilson and Kelling 1982; Moore and Kelling 1983; Lee-Sammons and Stock 1993).

-

Community policing favours foot patrols by the police which allows the police officer to experientally "learn his beat" (Alpert and Dunham1992, 432).

-

Community policing supports the idea that local police officers function as "problem brokers" and coordinate the communication with (other) public institutions and the members and associations of the community.

-

Community policing implies a special cooperation between the police and the citizens for crime prevention. Recurring problems are supposed to be solved by going back over and over to the same places in order to evaluate the efforts of both sides (Rosen 1990, 5)

-

Community policing tries to involve every citizen of a whole community in the activities to reduce and control acute crime problems, drug markets, fear of crime, the decline of the neighbourhood in order to improve the quality of life in the community (Trojanowicz 1990, 6).

-

Community policing is based upon the idea that the activities of the police have to be extended in the communities to become an institution that cares and coordinates efforts to improve social cohesion, if and at times where a diffusion of the community takes place and ties among organizations and citizens of a community become weaker. Crime control in general and combatting acute particular crimes remain still important aspects of policing in everyday practice (see for Crime Prevention: Moore 1996, 4). But community policing has its main focus on keeping the public peaceful, on mediating conflicts, and on coordinating efforts to improve the whole quality of life in the community (Feltes and Gramckow 1994).

Problem Oriented Policing

The police authorities have always tried, in addition to clearing up reported criminal incidents and to chasing suspected offenders, to solve problems occuring in their jurisdiction. Individual police officers took always care of problems they were faced with in their beat while on duty. But the concept of what a police problem is all about was rather limited and, in a certain way, typologically concretistic (Moore 1996, 14). Keeping public peace and order, clearing a difficult or even dangerous traffic situation, providing first service in cases of personal emergency, effecting first measures and alarming other authorities like the fire brigade, helping people and animals out of acute trouble, providing guidance for persons in need of care, offering advise for precautionary measures with regard to crime prevention (e.g. installing alarm systems): this is but a selection of what a responsive and responseful police authority or representative may have done and still will do in their regular work. This is not to be contested. However, problems of that type are probably mere surface phenomena. Seen from the point of view of community policing they may emerge out of deeper seated, more far reaching if not structural problems affecting the whole social space and the social-psychological web of a neighbourhood, a small village, a little town or a certain region of a city or metropolitan area. In the past there existed no guidance or a concept on how to detect and tackle such problems in a community.

The philosophy of problem solving policing aims to improve exactly that situation. It was developed by Goldstein in 1979 out of frustration with the dominant, i.e. more technological if not technocratic model for improving police operations. At the time the police in the U.S. and in many other Western industrialized countries were much more concerned e.g. about how quick they were in responding to a call than in asking what may have caused the fact that the concrete call was the 55th arriving from that locality within the last three months .Accordingly it was important for them to look for the necessary evidence for immediate law enforcement and eventual criminal justice procedures, but it didn't matter that much what they did otherwise with persons or situations affected by the event once they arrived at the scene of a crime. The police administrations lacked a concept which offered the police officers ways and means to detect signs of problems behind the manifested problem, and particular techniques to address such problems if detected on the occasion or in the aftermath of the event. Problem oriented policing tries to develop such concepts. It has so far a strong community inclination. In accordance with Peak and Glensor (1996, 79) one can therefore conclude that problem oriented policing relates to different principles than community oriented policing, but that both are complementary. Problem oriented policing may thus be perceived as a strategy that puts the community oriented policing philosophy into practice. The police as organization is supposed to look for and to examine the underlying causes of emerging crimes and disorders, and to find long term solutions. When grasping the essence of the concept of problem solving policing every individual police officer should feel enabled to contribute to the continuous task of identifying problems, analyzing them rigorously, developing strategies to moderate or even eliminate them, and later to evaluate the outcome. Spelman and Eck (1987, 2-3) call this four stage problem solving process S.A.R.A.: meaning that the process involves scanning, analysis, response, and assessment (Moore 1996, 17).

According to Goldstein (1990, 32) problem oriented policing means an encompassing plan to improve the work of the police by focusing their attention on the most serious background factors which have far reaching consequences for all levels of the structure and the organization of their duties. Goldstein argues further that the usual police behaviours (strategies, tactics etc.) are oriented towards the wrong categories. Not a crime category such as murder should e.g. be decisive on what kind of facts the energy should be directed at and the methods should be applied. The police have instead to evaluate and search for the objective causes and subjective reasons (motives etc.) behind the open or at least easily tangible crime scene, and to develop proactive and long term problem solving concepts for an area of social conflict (Moore 1996, 14). This does not imply, of course, that a local police authority with a high incidence of homicide cases could or should undo a standing and suitably equipped homicide squad or department. Crimes that happen have always to be dealt with in terms of clearance and appropriate law enforcement. The guiding idea is rather pointing at a meta-level of everyday work. According to that idea the police work may just start on the surface of an event since that is often the way the responsible persons gain knowledge of what happens out there. Sometimes already a single event can be significant for what basically determines the trouble people and/or localities are suffering from. At least repeated events or continuous nuisances should make the police alert to look for other than the evident contingencies of the situation. They are supposed to pursue the contextual elements of crime in the community, beyond the concrete cases and independent of the traditional detective tasks and endeavours. To put it in more classical criminological terms: they are expected to tackle the root causes of crime (Moore 1996, 16) in a given environment, and not just to deal with the surface of singular crimes or series of offences originating there by the one or the other coincidence of different circumstances. Consequently should individual police officers not restrain themselves to think about single case solutions but rather strive to contribute to the development of complete societal problem solution strategies. The latter should then trickle down in the organization, structure, and the training of the whole police corps, in particular with regard to sensitize new recruits and to hold alert already qualified experienced officers(that´s why Torstensson called Problem-Oriented-Policing knowledge-based-Policing, Torstensson 1996, 14) .

Goldstein argued that several steps must be taken in order to improve the quality of police responses. Eck and Spelman (1987, 3) seem to offer a suitable concept so far. They developed a twelve step model of what a problem oriented policing agency should do:

-

Focus on problems of concern to the public.

-

Zero in on effectiveness as the primary concern.

-

Be proactive.

-

Be committed to systematic inquiry as a first step in solving substantive problems.

-

Encourage the use of rigorous methods in making inquiries,

-

Make full use of the data in police files and the experience of police personnel.

-

Group like incidents together so that they can be addressed as a common problem.

-

Avoid using overly broad labels in grouping incidents so separate problems can be identified.

-

Encourage a broad and uninhibited search for solutions.

-

Acknowledge the limits of the criminal justice system as a response to problems.

-

Identify multiple interests in any one problem and weigh them when analysing the value of different responses.

-

Be committed to taking some risks in responding to problems.

The Relationship between Problem Oriented Policing and Community Policing

Police experts were looking in the USA for two decades for alternative ways to reduce the steady increasing crime rates and to combat crime through preventive measures (Lee-Sammons and Stock 1993, 157). Problem oriented policing and community policing have both the same philosophical roots and share according to Moore and Trojanowicz (1988, 11) some important characteristics:

-

decentralization in order to encourage officer initiative and the effective use of local knowledge.

-

geographical rather than functionally defined subordinate units in order to develop local knowledge.

-

close interactions with local communities in order to facilitate responsiveness to, and cooperation with, the community.

Problem oriented policing mainly tries to solve regional crime problems, however, the main focus is the solving of crimes and the underlying causes of the crime through restructuring of the police force and changes in the police organization. The main focus of community oriented policing is on the other hand the improvement of the relationship between the police and the citizens. Both concepts overlap in the area where problem oriented policing is depending on information of the citizens and a good relationship with the community. Further on in areas where potential conflict in the population leads to conflicts which problem oriented policing wants to solve, such conflicts would not have occurred through community policing. Each community oriented police work includes problem solving strategies, but the complete problem oriented police work is not necessarily community oriented. Problem oriented policing does not necessarily include long term evaluations in order to guarantee that the solutions to the problems will be long lasting (Trojanowicz and Bucqueroux 1994, 17). The interventions through problem oriented policing can change the structure of the community, they are, however, limited since the police are coming into the community, make changes and disappear. This does not apply for community oriented policing since in this case the police come into the neighbourhood/community, stays there and take on the responsibility to improve the quality of communal life (Hoover 1992, 10).

Peak and Glensor (1996, 95) engage, as already mentioned above, in conceiving of an integrated model called community oriented policing and problem solving (COPPS). They describe the essence of their concept as follows:

"Community oriented policing and problem solving is a proactive philosophy that promotes solving problems that are criminal, affect our quality of life, or increase our fear of crime, as well as relate to other community issues. COPPS encourages using various resources and police-community partnerships for developing strategies to identify, analyze, and address community problems at their source".

Police in the Eyes of Citizens

The question is now how those ideas are related to the subjective world of the citizenry. Do people accept the philosophy? Would the citizens be prepared to have the police integrated into their interpersonal and communal affairs? How would this affect their attitudes towards the police forces in general, since there are a couple of other policing authorities in modern states than just the particular local one? Would the eventual positive attitude toward problem oriented policing lead to a lasting cooperation with police officers and institutions? Is it foreseeable that all, the majority or at least a substantial and evenly distributed minority of the community members will feel instigated to engage in further improving the local social fabric. Will the citizens do this in a constant and wise manner and enhance the basic quality of life for all residents (visitors, commuters etc.)? What do people expect the new police to be like? What kind of views do the citizens have with regard to the new definition of the situation?

We were up to date not able to find any study addressing those and other related questions in a specific and coherent way. It seems therefore that the criminology, criminal justice and police research community has hitherto rather speculated on behalf of the people instead of asking them directly. There exist data, however, explicating one or the other aspect of citizens attitudes toward, expectations of, and experiences with the police in other contexts, but not explicitly to test if problem solving policing would be accepted by the citizens. Perhaps scholars relied in a more global an indirect manner on relevant results when they developed and worked on their models of problem and community oriented policing. We decided, however, to refrain from further refining conceptual issues and to take views of citizens and citizens expectations of problem solving policing (including community policing) as an empirical issue. In doing so we had to rely on already available survey materials and particular research results. Since those were, as a rule, not collected with the aim to clarify the topics of our analysis we have only limited possibilities to let the data speak convincingly in every respect. Sometimes the original data show a close connection to questions of problem oriented or community policing, and can therefore easily be interpreted within our framework of thinking. Sometimes we have to try harder to make new sense out of original results. Data have to be recoded or regrouped before they fit into the different concept of our analysis. The reinterpretation of results collected (hopefully) under a certain theoretical perspective different from one´s own is always a risky endeavour. We are aware of this and hope that we at least have not grossly distorted the meaning of the selected data by our procedures.

There is one common theme of problem oriented policing and community policing. Both stress the fact that the relationship between the police and the community/citizens are of utmost importance. In the eyes of the American citizens is the most important duty of the police to protect and serve (Lee-Sammons and Stock, 157). However, what the citizens exactly want from their police force and how they view their duties and obligations seems quite ambivalent. In general citizens favour a strong police force. However, they often do not report crimes to the police, and if they do, the level of their satisfaction with the police varies and is generally not extraordinary high. We will in a first step examine how much confidence the German citizens have in their public institutions and among them in the police.

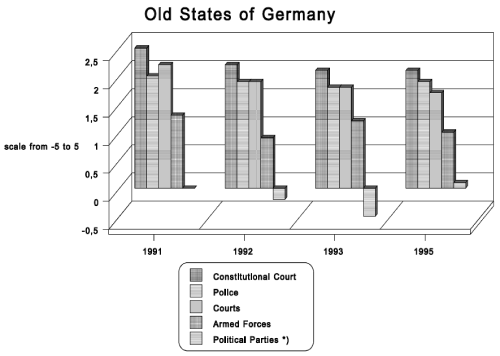

As one can see in figure 1, there exist substantial differences between the old and new States (i.e. Laender) of the Federal Republic of Germany. The confidence in nearly all public institutions is in the old States much higher than in the new States. In the old States we find only in 1992 and 1993 that the citizens viewed the parties negatively. The constitutional court was ranked highest in the old States as well as in the new States, even though in the latter the level of confidence was somewhat lower as compared to the old States. Courts were ranked very high in the old States and with the exception of 1991 fairly high in the new States.

Figure 1: Confidence in Public Institutions

Source: IPOS 1995

5 = trust completely

-5 = do not trust at all

*) In 1991 the question for political parties was not asked.

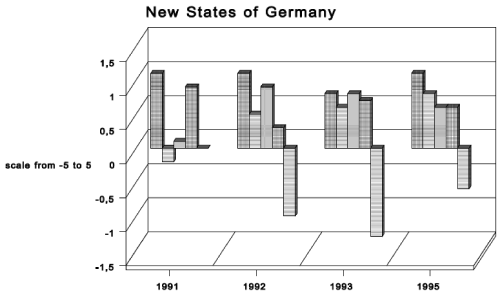

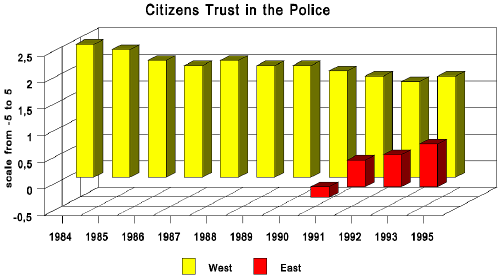

Figure: 2

Source: IPOS (Institut für praxisorientierte Sozialforschung); "Einstellungen zu aktuellen Fragen der Innenpolitik 1995 in Deutschland," pp.41-43

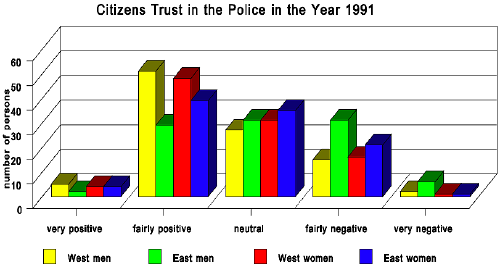

Source: Kreuzer, A.; Görgen, T.; Münch, V.; Schneider, H.; "Delinquenz im Systemvergleich" In:Boers, K.; Ewald, U.; Kerner, H.-J.; Lautsch, E.; Sessar, K.: Sozialer Umbruch und Kriminalität. 1994, p.161.

In the Survey were 100 persons per category (west men, east men, west women, east women) interviewed.

The police in the old States received a ranking on the second or the third position. That means that the West German citizens show a high and rather stable level of confidence in police but, in the long range, trust is slowly but steadily decreasing since 1984. East German citizens answered in quite a different way. In the first survey that included the new States the average result was negative. No other German survey had ever produced negative police rankings. Results did not even come near to zero. So this particular result can be taken as sign for deep seated distrust in that type of government agency normally representing, to speak with Max Weber, the monopoly of legitimate force of the State. The comparatively low confidence in the police can be explained by the past experience of the citizens with the peoples police (Volkspolizei) in the former German Democratic Republic. It seems that the distance to, if not the contempt of the all-intruding State Secret Service (Staatssicherheitsdienst) heavily influenced the attitudes of the citizens towards the police. The so-called Stasi was organized as a distinct and separate department (Ministerium) of the central government like, for example, the Department of Justice or the Department of Agriculture. The Stasi had central, regional, and local offices and under certain circumstances additional specialized offices. The Stasi was therefore not part of the regular police forces but had, inter alia, the power to interfere with police operations, to give them directions, or to take over a case. It was, by the same token, the strong arm of the leading party, the Unified Socialist Party of Germany (Sozialistische Einheitspartei Deutschlands) that owned the state in political terms. So the Volkspolizei was in many ways dependent on the Stasi and on the dominating party politics. After the German unification the police force in the new States was completely restructured and built up new along the Western democratic model. But it obviously took a while in this process to deal effectively with the shadows of the past (Murck 1992, 16). On the one hand the citizens had after the unification a very high level of insecurity and expressed a need for a strong police force, but on the other hand they could not easily overcome their generalized distrust in any kind of police force given their experience with the repressive aspects of the old regime. The ranking is improving now rather quickly. Murck found also in his study that the citizens of the new States developed a much better relationship with their new police rather quickly. 22% of the interviewed citizens in his study reported that the relationship towards the police is much friendlier, 58% reported that it is slightly better and only 16% reported that the relationship did not improve at all. It is interesting that males from the East had the highest percentage of very negative or at least fairly negative attitudes towards the police while the women in the new States exhibited a far more positive orientation.

In East Germany governed a social insecurity due to the need of reorientation and restruction of the social system. This insecurity is not only- as described above - being realized by the East German population, but also brings about a change in the polices jobhandling and shows up in the realization of personal interests and needs.

In 1991 Rafael Behr studied a police department in the new federal states for several weeks. He made the following observations: Most police officers felt personally burdened especially due to the increase of robberies and bank robberies, a fact which barely existed in the former GDR. They were also more frequently exposed to life threatening situations, the perpetrators were more brutal and using weapons, circumstances they were not used to. Therefore the police officers felt no longer that the criminals "inferior" to the police. In earlier times there was no need for the use of weapons; this was regulated by the government and MFS-apparatus. The police officers showed great fear of being victimized themselves (Behr 1993, 70). Furthermore Behr found that the relationship of the East Germans police with the population was after the unification most problematic. Most contacts between police and the population appear in cases where citizens ask for their help. However, the traditional East German police force barely sought contact towards the citizens. There was a tendency to regulate state affairs quickly and there was no understanding of long discussions with the citizens leaving alone the fact to involve them in police matters. It is in this context interesting that the absolute number of contacts between East German police and the population is far lower than in West Germany (p.74). Behr talks about an `informal control moratorium’ of the East German police (p.35). Behr mentions several reasons for the small amount of contacts initiated by the police. Next to insufficient technical equipment (like search electronics), there exists an unconscious fear to provoke feelings or remarks made by citizens who would treat the contact to the police as a form of control and which reminded them of the unpleasant relationship between them, the police and the former Stasi.

All together, the East German police makes an insecure appearance toward the population. The reason for it is found in their vulnerability due to their collective and not their personal past. Therefore they tend to avoid any contact to the population, which goes beyond the necessary measures and the police forces in the five new States will have to come an even longer way as the counterparts in the old States to incorporate the principles of community and problem oriented policing. The same is true for the citizens in the new States of Germany which have to learn that the police can be trusted and can be a "friend and helper".

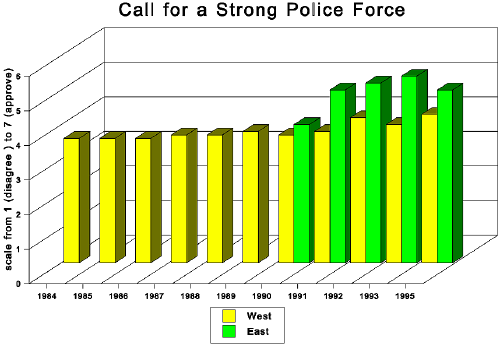

As figure 3 shows the citizens of Germany call generally for a strong police. This call increased over time and goes hand in hand with experiencing more problems in general and greater feelings of insecurity in society. The extent of the wish to be guarded by a strong police force is much more pronounced in the new States of the united Germany. Accordingly the call for a strong police force is substantially higher compared to the old States of Germany which indicates a higher level of subjective insecurity in the new States. Asked whether the police are very important for the protection of the citizen answered in 1991 49% of the citizens in the old States and 63% of the citizens in the new States of Germany accordingly, while only 5% in the West and 2% in the East reported that the police are not important at all.

Figure: 3

Source: IPOS (Institut für praxisorientierte Sozialforschung), "Einstellungen zu aktuellen Fragen der Innenpolitik 1995 in Deutschland." pp. 22, 25

The German population tends to have positive attitudes towards their police in general. This was aptly shown in the past, for example by Stephan (1976, 411,413) in his Stuttgart survey. Around 96% of the citizens of that city with a population of 600.000 thought that their police had a good reputation and police men/woman were decent people. 95% thought that police officers were friendly people and 87% of the inhabitants found that they should be more honoured. Kerner conducted in 1976 a study on the state of domestic security in Germany. A representative sample of (West) German citizens (N = 2,000) and a quota sample of young police officers (N= 1,172) were questioned about a couple of problems regarding the structure and development of crime, fear of crime, and police-citizens relations. The police survey allowed additional questions for the latter aspect. When asked whether they feared to get into trouble with the police 65% of the population answered with not at all, and an additional 19% with rather seldom (Kerner 1980, 439). However, it is interesting to note that the police officers were more sceptical in that respect. Kerner asked them about their heterostereotype of peoples expectations: 63% of them thought that the general population would expect trouble with the police (Kerner 1980, 485). Asked about their own fear to get confronted with citizens 18% of the police officers responded with constantly or often, and an additional 29% with at least sometimes (Kerner 1980, 478). The officers opinions may have reflected their tendency to generalize from single, but nevertheless repeated problematic encounters with normal people in public. Therefore they tended to consider themselves more friendly towards the citizens than they believe these would be willing to recognize. In the 70ies the public relations slogan “The police, your friends and helpers” was quite popular and often utilized, inter alia, in newspaper ads. The police officers liked this slogan: 83% reported that the advertisement was completely or mostly correct. But they expected that only 49% of the normal population would consent to this statement as well (Kerner 1980, 486). In addition believed the police officers that 18% of the population would think it is completely true and 50% that it is rather true that people are happy when not seeing and not hearing the police at all (Kerner 1980, 494).

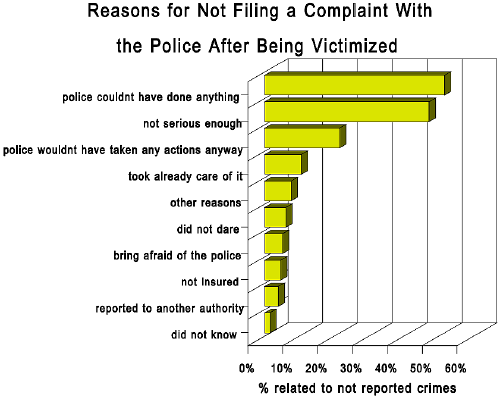

The question is how far this ambivalence and distance on the part of the population as indicated in police heterostereotyping reflect the true opinion of the people. For those basic attitudes would probably hamper, inter alia, the development of effective problem and community oriented policing schemes. We do not have adaequate data to answer the question directly. When trying to find evidence that allows at least indirect conclusions one can, in our opinion, partly rely on victimization studies in so far as these studies analyse victims crime incident reporting behaviour. The latest German study was done by Heinz and Spieß (1995) in the twin-city Ravensburg/Weingarten in South-Western Germany. They looked at the reasons why citizens did not report their victimizations to the police. Around 70% of the victims did not report the crimes to the police, which stands in great contrast to the above mentioned findings that the citizens in Germany are in favour of a strong police force. Their results imply more a kind of reduced expectation of citizens toward the police than a real (socio-psychological) distance.

As figure 4 shows slightly over 50 percent of the citizens who became the victim of a crime did not report the event to the police since they thought the police couldn't have done anything about it or there was not enough objective evidence for the commitment of a crime. In addition reported 47 percent of the citizens that the committed crimes were not serious enough to be reported, or that no damage occurred. These results indicate that around half of the citizens do not consider their victimizations as serious enough to outweight the endeavours (and probable further nuisances) of reporting them to the police. Besides these facts show citizens a very pragmatic and realistic adjustment towards their victimization by stating (21.5%) that the police would not have done anything. Of particular interest is that 85.1 percent of the citizens who were victimized by a aggravated or simple assault did not report these crimes to the police.

Figure: 4

Source: Heinz, W.; Spieß, G.; "Opfererfahrungen, Kriminalitätsfurcht und Vorstellungen zur Prävention von Kriminalität." p.24

There seems to be an ambivalence in the opinions of the people about, and their satisfaction with the police in general. This picture is further supported by a look at the level of satisfaction especially with the police performance. People appear not to expect too much in terms of police efficiency and effectiveness. The police are considered to be necessary agents of control in modern societies. They are therefore accepted as part of the social fabric. Since every form of (formal) social control bears both aspects, helping and restricting, seemingly contradictory opinions may actually not contradict each other but rather complement each other. To put it in simple words: The police should always be present immediately if I need care and help but, of course, they dont need to stick their nose too much in my affairs. The others are the real criminals, they need to be chased. Good citizens just happen to make errors sometimes or they can not always avoid to bypass the laws and regulations which are too strict anyway: Therefore the police dont have to ask for a formalistic way of law abidance, they have instead to show flexibility and indulgence. Those considerations may eventually lead to an integrated set of mixed feelings toward the police among the people. Generally positive attitudes may prevail even if one does not really like police authorities in a given situation of State and society, since one may be well aware that all other social institutions or agencies will provide even less help and emergency assistance than the police will normally do. Of course have autocratic or dictatorial States quite fundamentally different problems compared to democratic societies, but we shall not deal with that particular question here. General positive attitudes on the societal level allow further critical attitudes to-wards the local police and vice versa. There seems to be a proximity effect in that the evaluation of local conditions is more open to experiential influences out of direct police-citizen contacts and out of indirect knowledge stemming from relatives or friends experiences and from community gossip. We can approach the tendencies of these questions partly by looking at recent surveys.

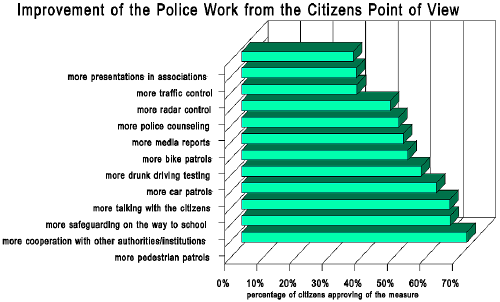

In Kerners German study people were asked to evaluate police efficiency in their immediate neighbourhood. Only 17% were mostly or fully discontent whereas 82% showed different levels of satisfaction (32% partly content, 38% mostly content, 12% completely content). It is interesting to note that the police officers came quite close in their estimate of what the population thinks of local policing; they had, however, a slightly more negative direction in their answers: 12% of the officers thought residents to be mostly or fully discontent whereas 73% assumed they would be satisfied (39% partly content, 33% mostly content, 1% completely content); around 10% did not dare to take a clear position (Kerner 1980, 443 - 493). In a more recent study in Unna, Germany, an industrial town in the Rhein-Ruhr-region of Germany, citizens were asked in which way they wanted to improve the work of the police. The answers can be interpreted to a certain extent as expression of satisfaction vs. dissatisfaction with local policing.

As one can see in figure 5, when the citizens were asked if the control through the police should be increased, they tended to the notion that they do not want to see the police in all areas with potential interference of policing with their own habitat or routine activities. The number of citizens who were in favour of more radar control, more traffic control, and more drunk driver testing were fairly low. This result fits very well into what Kerner found in 1976 as police heterostereotype of peoples attitudes is concerned: Only 6% of the officers said that the German population would prefer the police to enforce traffic laws; however, the top issue was guaranteeing peoples security (45%). When asked “In what respect do you think that the population feels the police control too much?” around 76% ranked traffic law enforcement first (Kerner 1980, 495). The police as law enforcers are esteemed in as much they control and catch the so-called true criminals, and the German police officers were well aware of this basic attitude: around 88% thought the people would like them to enforce the law and only 3% meant they were considered to be too harsh. The criminals are more or less out there or at least the others for the standard population. As a consequence we, the law abiding citizens, need not real control but rather advise, care, and help. Given this type of attitude one would expect that people condone or even seek all forms of policing representing the promise of good public order and peace. So far the public seems also basically be in favour of the positive issues built into concepts of community and problem oriented policing.

Figure: 5

Source: Bürgerbefragung der Kreispolizeibehörde Unna, Dez. 1994

The inhabitants of Unna can be taken as an example: they favoured to a high degree policing measures such as more talking with the citizens, more police counselling and more cooperation with other authorities/institutions. They consequently did not so much vote for increasing the patrols by bikes and cars, but preferred to see more pedestrian patrols by the police. This survey clearly indicates that the citizens like to perceive the police as friends and helpers and they would support endeavours to improve the work of the police force much in the sense of what community and problem oriented policing propose.

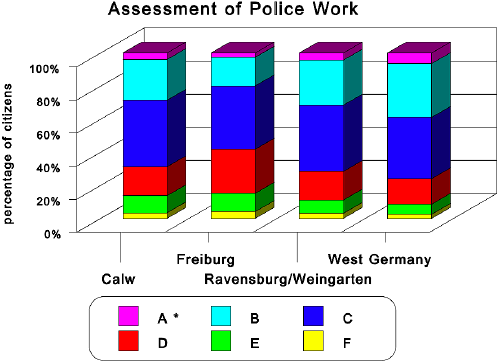

A further assessment of the quality of the local police work can be found in the study by Heinz and Spieß (1995) for the cities of Ravensburg and Weingarten.

Figure: 6

Source: Heinz, W.; Spieß, G.; "Opfererfahrungen, Kriminalitätsfurcht und Vorstellungen zur Prävention von Kriminalität." p.39

*A,B,C...... = School Grades, where A means very good and F complete failure

The citizens were asked to evaluate the police on a grade scale of one to six. As figure six shows the city inhabitants were, with a grade point average of 3.1. fairly satisfied with the current work of the police in their community. This grade is slightly lower then the one for the Federal Republic of Germany (Old States) which may be due to the above mentioned proximity effect. The younger age groups scored the lowest and were not so satisfied with the work of the police. On the other hand were those citizens who had just recently seen a police patrol in their neighbourhood much more content with the police work than any other group. Victims and nonvictims among the citizens assessed the police work not structurally different but, however, a negative effect seemed to emanate from multiple victimizations. While the difference between one time victims and nonvictims is rather small assess multiple victims the work of the police quite negative.

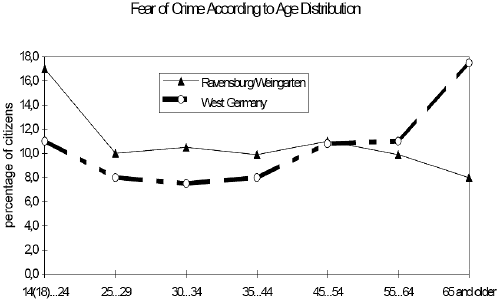

Figure: 7

Source: Heinz, W.;Spieß, G.: Opfererfahrungen, Kriminalitätsfurcht und Vorstellungen zur Prävention von Kriminalität, p. 33

Fear of crime is a very important measure on how well the citizens feel in their neighbourhood and how high is the quality of life (Sampson 1996; Wikström 1996). In the latest survey in Germany about the "anxieties of the nation" the Germans ranked fear of crime after unemployment as the second highest problem. It is further a widely supported result of research on fear of crime that the level increases with age and that old women have the highest level while they have in reality the lowest risk of becoming a victim of a crime (Wikström 1996, 23, 25). However, Heinz and Spieß (1995, 33) report quite different results for the cities of Ravensburg/ Weingarten. As figure 7 shows have in their sample young people the highest level of fear of crime. This is a bit surprising result since it seems as if it has not be found anywhere else until now. When they compared their results with the results of a simultanously conducted survey for the German general population they found that the level of fear of crime among the young in Ravensburg/ Weingarten is almost as high as the level of fear of crime for the age group 65 and older for the German population. This is perhaps an indication for the beginning of a new trend. When Heinz and Spieß looked at gender differences they found that especially women under 25 years of age in Ravensburg/Weingarten had an extraordinary high level of fear of crime while the level of fear of crime for women over 65 years of age was moderate and far below the German average. One can only speculate what happened in Ravensberg/Weingarten and it has to be seen if these results will be found again in different cities and countries.

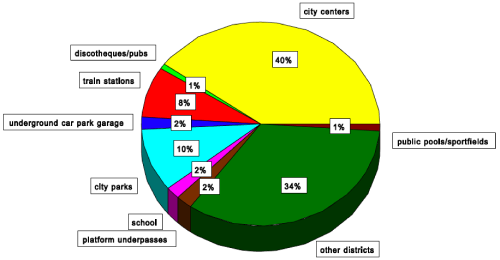

Figure 8: Fear of Insecurity With Regard to Different Locations

Source: Heinz, W.; Spieß, G.; "Opfererfahrungen, Kriminalitätsfurcht und Vorstellungen zur Prävention von Kriminalität." p.60

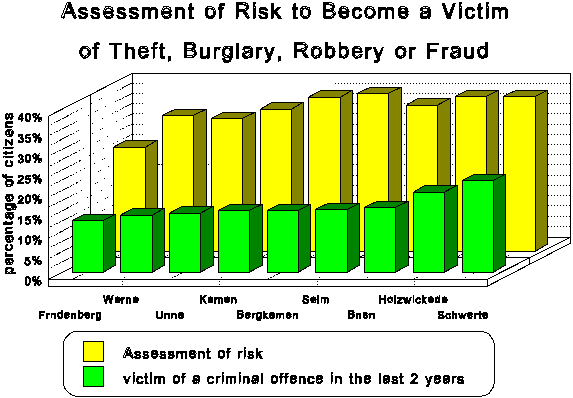

Heinz and Spieß (1995, 60) found that citizens have feelings of insecurity in particular in the center of cities 40% (see also Wikström 1996, 1). 10 percent of the citizens have feelings of insecurity in city parks and 8% at train stations in cities. Other places do not play a major role or cannot be defined. Their findings support what Wikstroem calls "hot spots". Wikstroem (1995, 441-43) could identify in Stockholm hot spots which were peaceful during the day and very insecure in the late night and on weekends. Problem and community oriented policing could be the answer to control such hot spots and by the implementation of little preventive measures they could probably be made safe places. Whether this would change the feelings of security of the citizens has to be seen.

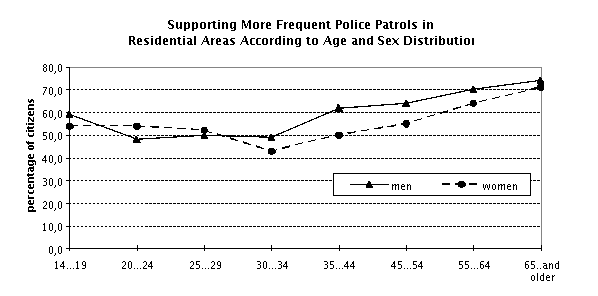

Figure: 9

Source: Heinz, W.; Spieß, G.; "Opfererfahrungen, Kriminalitätsfurcht und Vorstellungen zur Prävention von Kriminalität" p.38

The majority of the citizens of Ravensburg/Weingarten are in favour of more frequent police patrols in their neighbourhoods and this wish is increasing with age and independent of the gender of the citizens. While close to 60 percent of the male citizens age 14 to 19 favour more frequent police patrols, increases the percentage to just over 70 percent for the age group 65 and older. Quite similar looks the percentages for the females which went from 55 percent to just above 70 percent. If one takes into consideration the results of the study in Unna one can be quite sure that the citizens of Ravenburg/Weingarten would also prefer more foot and bicycle patrols and not police car patrols. This again would go hand in hand with the postulates of problem and community oriented policing.

The call for more presence of the police was also confirmed in the study of Murck (1992, 16). The citizens also asked for more police-community relations. Overall supported the citizens the principles of community and problem oriented policing and were not asking so much for harsher and tougher measures in the fight against crime. Very similar results reported also Heinz and Spieß (1995, 39) for the cities of Ravensburg/Weingarten where the citizens were asking for better leisure time programs for juveniles and all sorts of measures to improve life in the cities rather than relying on harder measures in the fight against crime. The citizens favoured social measures as the best way to reduce feelings of insecurity and fear of crime (see also Sampson 1996; Wikström 1996, 2). These results clearly indicate that the concepts of problem oriented and community policing to a certain degree reflect what the citizens expect and want from their police force even though the results are far from being clear and conclusive.

Figure: 10

Source: "Bürgerbefragung der Kreispolizeibehörde Unna, Dezember 1994."

Discussion

We did find in the evaluated surveys support for the notion that the citizens view the concepts of problem and community oriented policing in a favourable way. We further detected that the expectations of the citizens to a certain degree reflect what problem and community oriented policing postulate. However, since the concepts are at this moment not sufficiently operationalized one could argue that we can get under the umbrella of problem and community oriented policing everything which is new in the police work. Therefore we agree partly with Bayley (1994, 278) who concludes that one will never know whether community policing (as well as problem oriented policing) will be successful since problem and community policing means too many things to different people. The practice varies so much that any evaluation will be completely challengable or at least in part of not representing what problem and community oriented policing postulate. A central question seems to be in the case of problem and community oriented policing that we do not have anymore a clear role for the police: are the duties of the police to combat crime or are they supposed to work like a socialworker? If anything in between seems suitable: what is the appropriate mixture and how could individual police officers combine the very divergent competences needed to fullfill the different tasks? In the case of problem oriented policing are the police supposed to identify the main problems of certain groups in the population and to help solving them. However, population groups are not homogenous units and different groups identify problems different and also suggest different ways to solve them. Even if the police would be able to acknowledge the various sources of trouble it would often be impossible to find an agreement on how to solve them when the police are forced to work together with different subgroups and organizations in a given community. This would lead improve to a certain degree the feelings of security on the one hand, but would also lead to resignation and frustrations on the other hand for some of the residents who do not approve the suggested strategies in order to solve the problems.

The concepts and the combination of problem and community oriented policing sound very good in theory and might work quite well (for example Skogan 1996, 25; Torstensson 1996, 5) in countries which adhere to the opportunity principle (e.g. USA; Canada, the Netherlands). They still sound good in theory for countries with the legality principle (e.g. Germany, Austria, and Switzerland). In countries with the legality principle are the police obliged by procedural law to enter prosecution in every case where exists preliminary suspicion that a crime was committed and to report it to the prosecutors office. Therefore the concepts are doomed and would probably fail even before one would start to implement them into practice.

The central part of problem and community oriented policing is that the relationship between the police officers and the citizens should be improved. This implies that when a police officer wants to built a trustworthy relationship with citizens in order to have a better understanding of the problems of the community he/she will hear about situations and events which are in a strict sense according to the laws illegal. In countries with the legality principle this would have the consequence that the police officer would have to report this "confidential knowledge" of a crime to the prosecutors office since the police have in general no discretion whatsoever and have to leave the final decision about to prosecute or to drop the charge to the prosecutors office. In order to built up a trustworthy relationship, which is essential to problem and community oriented policing, the police officer has to have at least some discretion on how to react when he is informed about acts which constitute according to the laws a crime or are at the borderline. If the officer is forced to report the pettiest offences eventually to the prosecutors office one cannot expect that he will built up a meaningful relationship with any given community. Discretion and flexibility in how to interpret certain situations for police officers seem to be the essential parts if one wants to implement problem and community oriented policing in a community. If one takes these postulates seriously the concepts cannot function in countries with the legality principle unless they fundamentally change their penal procedural law.

Despite this specific problem for countries with the legality principle summarizes Lustig (1996, 35) rightly that the philosophy of community policing (as well as problem oriented policing) will in any system be defined by the fact that through the implementation of community and problem oriented policing neither the strategy of the police work, nor the logic of guaranteeing security, nor the power of the state will be changed. These three positions will be strengthened through the concepts of community and problem oriented policing, thus leading eventually to a netwidening effect. While this is basically true, indicate the results of views of citizens and citizens expectations that they are in favour of core elements of community and problem oriented policing and that through the implementation of these concepts the feelings of security and thus the quality of life can be improved for the citizens (Hermannstädter 1986, Hermanutz 1995, 141). Therefore netwidening effects are not necessarily negative unless they are used to control citizens in an intrusive way (Weitekamp 1989). Some projects in the United States of America also support this conclusion, since they were able to reduce the number of crimes committed but even more important to reduce the fear of the citizens to become a victim of a crime. In addition they found in these projects that the level of satisfaction with the police was increased among the citizens (Lee-Sammons and Stock 1993, 160). However, despite the reported success of these projects on local levels one has to be sceptical that the degree of satisfaction in a given population at large with the police work would overall improve. In order to improve the general level of satisfaction with the police one would have to be able to show on a large scale that through measures of problem and community oriented policing the quality of life improved. The citizen by himself will hardly recognize a restructuring of the police force and the implementation of problem and community oriented policing unless it happens on a large scale, is continuously reported and favourably backed up by the media, or he gets directly involved. Scepticism is justified also by the fact that especially problem oriented policing is calling for solving the underlying problems of crime. The experiences in the United States of America, where problem and community oriented policing was practiced and the relationship between the police, the citizens, and groups of the community was excellent and they all worked together, did not necessarily lead to solve problems of security and order in those communities. The reason for that is that the police cannot create jobs, improve the schools and get better teachers and often fails even to get the garbage collectors or street services better organized in order to improve the situation of a given community (Feltes and Gramckow 1994, 20).

If one examines the views of citizens who were asked about the perceived causes of the increasing crime rate and their suggestions with regard to measures for crime prevention one can clearly detect the dilemma in which communities are in: The factors citizens define as causal for the increase of crime are mostly structural or economic ones but when asked which preventive measures should be taken to reduce the crime rates they suggest primarily to increase the presence of the police in their neighbourhood. This short term measure can of course not solve underlying economic and structural problems in a city or community and the increasing rates of youth unemployment are as well not affected by more police officers in the streets (Heinz and Spieß 1995, 117). In general we find a tendency that citizens react to increasing crime rates with the call for more police and stiffer laws. This reflects the widespread tendency to hold on the one hand the state responsible for the shaping of own, personal conditions of life, and on the other hand to believe in the behaviour controlling power of the penal laws.

Conclusions

If one examines the above introduced results from various surveys and tries to draw a conclusion is the outcome that citizens have two major views and expectations towards the police:

-

German citizens want a strong police force with a high visibility in their neighbourhood.

-

German citizens want police officers that are their friends and helpers and are prepared and willing to handle all kinds of problems within the community.

-

German citizens want a police force which is based upon the principle of community and problem oriented policing.

-

What the German population wishes from their police cannot be achieved since the legality principle prohibits policing based upon community and problem oriented policing.

All together, concerning the surveys which we evaluated, do the German citizens have a strong idea what policing should be all about and in principle support the postulates of community and problem oriented policing. Even the East Germans are in principle open and ready for structural changes in the police and favour better relationships between the people, community, and the police but due to past experience in their "police state" they need some more time to overcome the past bad experiences. With regard to citizens opinions and expectation community and problem oriented policing find a fertile ground in Germany as well as Skogan (1996, 25) reports for the United States of America. The feelings of insecurity and thus the quality of life would probably increased if these philosophies would be introduced to the German police. However, as argued earlier the legality principle is prohibiting this. If one wants a better, more content citizentry who has low levels of fear of crime and feels safe in their neighbourhoods and communities one has to modify or to abolish the legality principle.

References

Alpert, G. P. and Dunham, R. G. 1986: Community Policing, in: Journal of Police Science and Administration, 14, pp. 212 - 222. Reprinted in: Dunham, R. G. and Alpert, G. P. 1993: Critical Issues in Policing. Illinois: Waveland Press.

Bayley, D. H. 1994: International Differences in Community Policing, in: Rosenbaum D. P. (ed.): The Challenge of Community Policing. London, pp. 278-281.

Behr, R. 1993: Polizei im gesellschaftlichen Umbruch. Ergebnisse der teilnehmenden Beobachtung bei der Schutzpolizei Thüringen. Holzkirchen: Felix Verlag.

Eck, J. E. and Spelman,W. 1987: Problem-solving : problem-oriented policing, in: Newport News. Washington DC : Police Executive Research Forum. Reprinted in: Dunham, Roger G. and Alpert, G. P. 1993: Critical Issues in Policing Illinois: Waveland Press.

Feltes, T. and Gramkow, H. 1994: Bürgernahe Polizei und kommunale Kriminalprävention, in: Neue Kriminalpolitik, 3, pp. 16 ff.

Goldstein, H. 1990: Problem-oriented policing. Philadelphia: Temple University Pr.

Heinz, W. and Spieß, G. 1995: Opfererfahrungen, Kriminalitätsfurcht und Vorstellungen zur Prävention von Kriminalität. Ergebnisse der Bevölkerungsbefragung in den Gemeinden Ravensburg /Weingarten im Rahmen des Begleitforschungsprojekts "Kommunale Kriminalprävention” in Baden – Württemberg. Konstanz.

Hermannstädter, P. 1986: Konzeption zur Erreichung von Bürgernähe, in: Schriftenreihe der PFA, pp. 102 – 126.

Hermanutz, M. 1995: Die Zufriedenheit von Bürgern mit den Umgangsformen der Polizei nach einem mündlichen Polizeikontakt - eine empirische Untersuchung, in: Thomas F. (ed.): Kommunale Kriminalprävention in Baden-Württemberg. Holzkirchen: Felix Verlag, pp. 37-158.

Hoover, L.T., in: Kratcoski, P. and Dukes, D. (eds.): Issues in Community policing. 10. Highland Heights, Ky, Acad. of Criminal Justice Sciences, Northern Kent.

IPOS (Institut für praxisorientierte Sozialforschung)(ed.): Einstellungen zu aktuellen Fragen der Innenpolitik 1995 in Deutschland.

Kerner, H.-J. 1980: Kriminalitätseinschätzung und Innere Sicherheit. Wiesbaden BKA: Forschungsreihe Nr.11.

Kratcoski, P. and Dukes, D. 1995: Issues in community policing. Highland Heights, Ky, Acad. of Criminal Justice Sciences, Northern Kent.

Kreispolizeibehörde Unna (ed.) 1994: Bürgerbefragung im Kreispolizeibezirk Unna. Unna.

Lee-Sammons, L. and Stock, J. 1993: Kriminalprävention. Das Konzept des "Community Policing" in den USA, in: Kriminalistik, 3, pp. 157 – 162.

Lustig, S. 1996: Die Sicherheitswacht im Rahmen des Bayrischen Polizeikonzepts (unveröffentlichte Diplomarbeit). München: Ludwig-Maximilian-Universität.

Moore, M. and Kelling, G. 1983: To Serve and Protect: Learning from Police History, in: The Public Interest, 70, pp. 49-65.

Moore, M. and Trojanowicz, R. 1988: Corporate Strategies for Policing ,11.

Moore, M. 1996: Problem-Solving Policing and Crime Prevention (a paper prepared for the International Conference on Problem-Solving Policing as Crime Prevention).

Murck, M. 1992: Zwischen Schutzbedürfnis und Mißtrauen - Einstellungen zur Polizei bei den Bürgern in den neuen Bundesländer, in: Die Polizei , pp. 16ff.

Peak, K. J. and Glensor, R. W. 1996: Community Policing and Problem Solving. Strategies and Practices. New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

Radzinowicz, L. 1968: A History of English Criminal Law and Ist Administration from 1750, Vol. IV: Grappling for Control. London: Stevens & Son, p. 163.

Rosen, M.S., in: Kratcoski, Peter and Dukes, Duane (eds.): Issues in community policing. 5. Highland Heights, Ky., Acad. of Criminal Justice Sciences, Northern Kent.

Sampson, R. and Wikström, P.O. 1996: Lessons for Policing from Community and Crime Research: A comparative Look at Chicago and Stockholm Neighbourhoods (a paper prepared for the International Conference on Problem-Solving Policing as Crime Prevention).

Skogan, W. 1996: Evaluating Problem Solving: The Chicago Experience (a paper prepared for the International Conference on Problem-Solving Policing as Crime Prevention).

Sparrow, M. 1988: Implementing Community Policing. National Institut of Justice, Perspectives on Policing No.9.

Stephan, E. 1976: Die Stuttgarter Opferbefragung. Wiesbaden.

Torstensson, M. 1996: Implementing Problem-Oriented Policing (a paper prepared for the International Conference on Problem-Solving Policing as Crime Prevention).

Trojanowicz, R. (1990), in: Kratcoski P. and Dukes, D. (eds.): Issues in community policing , 6. Highland Heights, Ky., Acad. of Criminal Justice Sciences, Northern Kent.

Trojanowicz, R. and Bucqueroux, B. 1994: Community policing: how to get started. Cincinnati, Ohio: Anderson.

Trojanowicz, R. and Carter, D. 1988: The Philosophy and Role of Community Policing. Michigan State University, 17.

Weitekamp, E.G.M. 1989: Restitution: A New Paradigm of Criminal Justice or a new Way to Widen the System of Social Control. Ann Arbor: University Microfilms.

Wikström, P.O. 1995: Preventing City-Center Street Crimes, in: Tonry, Michael and Farrington, David P. (eds.): Building a Safer Society: Strategic Approaches to Crime Prevention. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, pp. 429 – 468.

Wikström, P.O. 1996: Policing Crime in Public, The Eskilstuna Project: Problem Picture, Preventive Measures and Citizens Attitudes ( a paper prepared for the International Conference on Problem-Solving Policing as Crime Prevention).

Author´s Address:

Prof Elmar Weitekamp / Prof Dr Hans-Jürgen Kerner

University of Tuebingen

Institute of Criminology

Corrensstr. 34

D-72076 Tuebingen,

Germany

Tel.: ++49 7071 297 6139 / ++49 7071 297 2044

Fax: ++49 7071 65104

Email: elmar.weitekamp@uni-tuebingen.de / hans-juergen.kerner@uni-tuebingen.de

urn:nbn:de:0009-11-3979