New Security Threats for Humanitarian Aid Workers

Peter Runge, Network of German Non-Governmental-Organisations in Development Cooperation Policy (VENRO), Bonn[1]

1 Tragic attacks on humanitarian aid workers

Two recent events in Afghanistan and Iraq highlight the current security threats for humanitarian aid workers: Firstly, in July 2004 the humanitarian aid organisation Médecins sans Frontières (MSF) stopped its operations in Afghanistan. This decision followed the targeted killing of five MSF aid workers in Northwestern Afghanistan in June 2004, a brutal act unprecedented in the organisation’s history. Afghanistan has become a dangerous place for aid workers: Since March 2003 more than 30 humanitarian aid workers have been killed. Secondly, in September 2004 the so-called “two Simonas”, staff members of the Italian non-governemental organization (NGO) “Un ponte per” (A Bridge for Bagdad) were abducted in Iraq and, fortunately, released in October 2004. Around 130 foreigners have been seized in Iraq in a wave of abductions that began in April. Most have been released, but around 30 have been killed. Due to the tense security situation in Iraq all the expatriate staff members of Western NGOs have been evacuated in the last months.

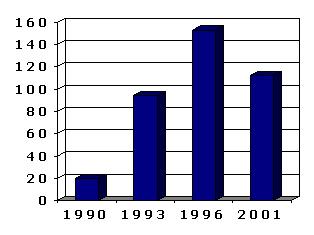

The events in Afghanistan and Iraq demonstrate that aid workers are increasingly seen as legitimate targets by those who identify them – wrongly – with the foreign policies of Western governments. The MSF staff members who were killed in Afghanistan, for example, were accused by the Taliban (who claimed to have been responsible for the attack) of carrying out US policies. The worsening of the security situation for aid staff is reflected in the statistics of reported “security incidents” per year (see United Nations 2002: 2):

Figure 1: Statistics of reported security incidents per year

2 What are the underlying causes of the new security threats?

First of all, since the beginning of the nineties, humanitarian aid and development organisations have been confronted with armed conflicts to an ever-increasing degree. The number of violent, almost always inner-state, conflicts has constantly been growing, and therefore, so has the number of aid missions. The UN has recorded a dramatic increase in the number of its peace missions, which are almost always accompanied by humanitarian aid and aid workers in action. A second reason is that non-compliance of the civil war parties with international humanitarian law is on the increase. Warlords and militia do not observe the internationally agreed rules on the protection of the civilian population in wars. A growing culture of impunity is coinciding with non-compliance with international law. Aid organisations are seen as simple targets that can be attacked without any major consequences for those responsible.

As supporters of the victims of wars and disasters, aid agencies are no longer regarded as neutral parties to the conflict. Moreover, since they transfer resources that are important for the warring parties, their aid to the suffering population gains a strategic role in war times. Furthermore, humanitarian aid has been increasingly politicized and been used as a substitute for unsuccessful political action or as a means of covering up or justifying military incursions in crisis areas. What used to be a clear demarcation line between humanitarian and military missions is now becoming blurred, which in turn is making it more difficult for aid organisations to maintain their neutrality. In its press release explaining the withdrawal from Afghanistan MSF blaims the politicization of humanitarian aid: “The violence directed against humanitarian aid workers has come in a context in which the US backed coalition has consistently sought to use humanitarian aid to build support for its military and political ambitions. MSF denounces the coalition’s attempts to co-opt humanitarian aid and use it to win hearts and minds. By doing so, providing aid is no longer seen as an impartial and neutral act, endangering the lives of humanitarian volunteers and jeopardizing the aid to people in need” (www.msf.org).

3 What can aid agencies do to protect themselves?

Improving security management within an organisation involves a number of aspects. It is important that the security issue is mainstreamed throughout the organisation. A coherent security strategy has to be in place as well as detailed regulations on implementation at the level of local operations and a code of conduct on what the organisation expects of its staff.[2]

4 Security strategy

The security of aid organisations must not be conceived and treated in purely military terms. Generally, there are three different security strategies: The first one aims at deterrence, the second at protection and the third at acceptance and recognition. A deterrence strategy aims at raising the risk of an attacker by threatening with counterviolence and inhibiting potential enemies. Armed escorts for aid shipments are an example of this strategy. The second strategy is aimed at one’s own protection and serves the purpose of making a potential attack more difficult. Examples are burgler bars, bullet-proof vests, controlled access to offices and housing and other measures making attacks more difficult. While the need for protection is understandable, it can result in a reactive “bunker mentality”. Dug in behind walls and barbed wire, one perceives the surroundings as a threat and loses contact with the people to the wellbeing of whom one really wishes to contribute. This is why NGOs primarily opt for the third approach to gain protection by acceptance and recognition among the civilian population in project activities and in working with the target groups. Involving the people and the local authorities in the planning and implementation of measures is to help achieve their feeling responsible for the protection of the aid workers. Fear among the population of the aid organisations being withdrawn and a loss of international support is an important protective element.

5 Security plan

An aid agency’s security strategy, which has been worked out at its headquarters, is put into concrete terms and regulations at local level. Staff members require clear orientations as to how they are to respond to crisis situations and who can or has to make what decisions. Reporting on and analysis of incidents are also important issues that require guidelines. Security planning at local level includes a risk analysis, working out a security plan, a code of conduct for the staff and guidelines for co-operation with other actors. Before a security plan is compiled at local level, a risk analysis ought to be conducted in a similar way to the assessment of the needs a target group of a planned project has. Here, potential threats are analysed on the one hand, and on the other, the vulnerability of the individuals working in the project is assessed. A risk analysis of this kind follows the equation: risk = threat x vulnerability.

Although the threat itself can only be influenced minimally in most cases, aid organisations can reduce their vulnerability by opting for an appropriate security strategy. Local or international staffs are vulnerable to certain threats to a varying extent. The following questions are asked in analysing threats: Who represents a threat? Why? What are the possible targets for attacks? How and where could attacks be launched? Checklists can be drawn up for these considerations, and security levels can be defined to classify certain situations.

6 Code of Conduct for the staff

Setting out from the insight that the security of aid organisations is not merely a question of equipment and technology but crucially depends on people’s behaviour and the way that projects are implemented, expectations also have to be clarified that an organisation has of its staff in its day-to-day operations.

Such a code of conduct aims at promoting an understanding of the relation between the type of project implementation and the personal behaviour of the staff on the one hand and the threat scenarios on the other. Employees are thus supposed to understand that they have concrete options in everyday life and work to reduce their vulnerability to certain threats. Additional important aspects that ought to be contained in such a document include teamwork, each individual’s responsibility for his or her security and that of the colleagues and, in particular, sensitivity towards other cultures (issues regarding clothing, alcohol consumption, the status of religion, relations between men and women). Statements on sanctions applied in the case of non-compliance with guidelines on behaviour depend on the organisation itself.

7 Colaboration with other actors

While co-ordination among NGOs and between UN agencies and NGOs is already taking place in various fields, it could certainly be intensified and is also of importance from a security angle. The UN addressed this with guidelines early in 2002 that are aimed at regulating collaboration between UN agencies and aid organisations (see United Nations Security Coordinator 2002). With the Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), the UN has created a coordination body for issues related to contents, while UNSECOORD (Office of the United Nations Security Coordinator) deals with security issues.

Furthermore, in any country in which security problems arise, the German Embassy takes precautions. It works out crisis plans in which the governmental organisations are integrated on a mandatory basis and the non-governmental organisations on a voluntary basis. The Foreign Office’s Crisis Response Centre in Berlin can be called on round the clock and is the contact for emergencies abroad occurring outside service hours. Its tasks include the early recognition of crises, precautionary measures and crisis management. As soon as a critical situation abroad has been defined as a “crisis”, overall control of subsequent handling of the crisis is transferred to the Crisis Response Centre. In crisis management, the Crisis Response Centre provides its experience and personal and technical resources, and it also assumes a co-ordinating role vis-à-vis other operational units of the Foreign Office that are consulted in the context.

8 Conclusion

On the one hand, on the operational level a well-designed security strategy is compulsory and – at the same time – an important contribution to improving the quality of humanitarian aid. Training for staff in security awareness and management is a central aspect of making these improvements. On the other hand, international humanitarian law needs to be enforced. Under the Geneva Conventions, both civilians and the aid workers who seek to help them are to be protected. UN Council Regulation 1502, passed in 2003 after the bombing of the UN Headqurters in Bagdad, affirmed that killing a humanitarian aid worker is a war crime.

We need a humanitarianism that is politically independent and impartial. Humanitarian aid workers just want to alleviate human suffering because there are no humanitarian solutions to political crises. Therefore, the best protection for humanitarian aid workers is to continue to build trust with the local population and to demonstrate that humanitarian aid is entirely separate from political or military agendas.

References

United Nations Security Coordinator 2002: Guidelines for UN/NGO/INGO Security Collaboration.

United Nations 2002: Report of the Secretary-General on safety and security of humanitarian personnel and protection of United Nations personnel, 15 August 2002.

Author’s

address:

Peter Runge

Kaiserstrasse 201

D-53113 Bonn

Tel.: +49 228 946 770

Fax: +49 228 946 7799

EMail: p.runge@venro.org

Internet: www.venro.org